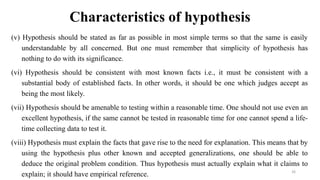

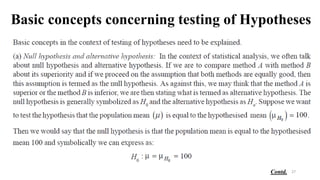

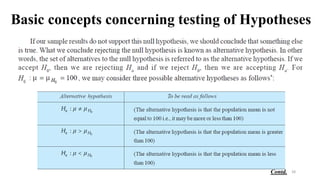

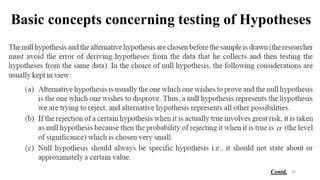

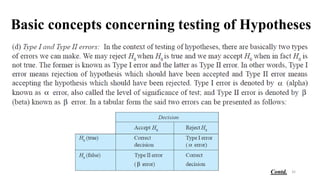

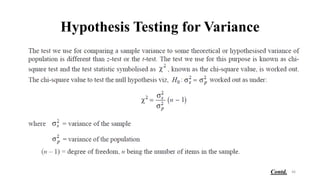

The document discusses research methodology and sampling design. It defines research as a systematic search for knowledge through objective methods. There are different types of research including descriptive, analytical, applied, and fundamental research. Research design is important as it provides a blueprint for how the research will be conducted, including the sampling, data collection, and analysis procedures. Developing clear hypotheses to focus the research and testing those hypotheses is also discussed.