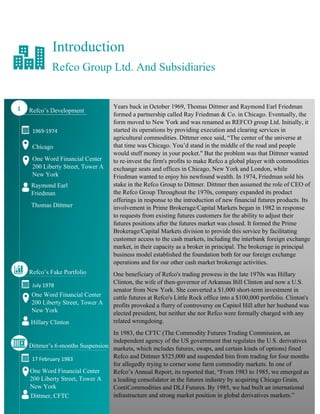

1. Refco Group Ltd. was formed in 1969 in Chicago by Thomas Dittmer and Raymond Earl Friedman and expanded throughout the 1970s and 1980s, becoming a global player in commodities trading.

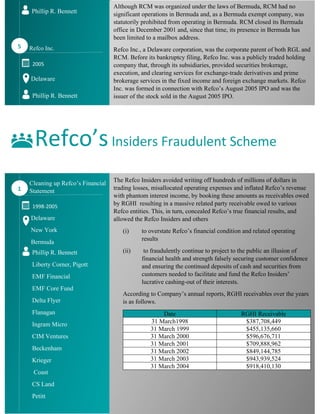

2. In the 1990s, Phillip Bennett became CEO and began fraudulent schemes to hide Refco's trading losses and expenses through fake receivables from related party RGHI, growing to over $700 million by 2005.

3. Bennett and other Refco insiders carried out an $800 million leveraged buyout in 2004 through THL Partners, allowing them to personally enrich themselves with $106 million while saddling Refco with debt, despite knowing of Refco's true financial situation.