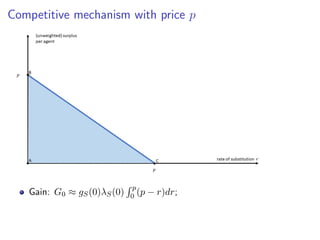

The document discusses inequality-aware market design, emphasizing how market designers consider wealth disparities among participants when creating structures for various markets such as housing, healthcare, and food. It highlights the importance of addressing the equity-efficiency trade-off and the implications of wealth on individuals' preferences and social welfare. Additionally, the paper outlines potential mechanisms for optimal market design that accommodates these inequalities within the constraints of incentive compatibility and budget balance.

![Framework – some observations

Individual preferences depend only on the rate of substitution:

r =

vK

vM

.

It will turn out that this implies that it is wlog to consider mechanisms

whose outcomes only depend on r. Let:

r ∼ Gj with positive density gj on [rj, r̄j].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-37-320.jpg)

![Framework – some observations

Individual preferences depend only on the rate of substitution:

r =

vK

vM

.

It will turn out that this implies that it is wlog to consider mechanisms

whose outcomes only depend on r. Let:

r ∼ Gj with positive density gj on [rj, r̄j].

Social preferences can also be expressed as a function of r:

µEB

[xB

K · vK + xB

M · vM ] + ES

[xS

K · vK + xS

M · vM ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-38-320.jpg)

![Framework – some observations

Individual preferences depend only on the rate of substitution:

r =

vK

vM

.

It will turn out that this implies that it is wlog to consider mechanisms

whose outcomes only depend on r. Let:

r ∼ Gj with positive density gj on [rj, r̄j].

Social preferences can also be expressed as a function of r:

µEB

vM

xB

K ·

vK

vM

+ xB

M

+ ES

vM

xS

K ·

vK

vM

+ xS

M

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-39-320.jpg)

![Framework – some observations

Individual preferences depend only on the rate of substitution:

r =

vK

vM

.

It will turn out that this implies that it is wlog to consider mechanisms

whose outcomes only depend on r. Let:

r ∼ Gj with positive density gj on [rj, r̄j].

Social preferences can also be expressed as a function of r:

µEB

EB

[vM |r]

xB

K · r + xB

M

+ ES

ES

[vM |r]

xS

K · r + xS

M

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-40-320.jpg)

![Framework – some observations

Individual preferences depend only on the rate of substitution:

r =

vK

vM

.

It will turn out that this implies that it is wlog to consider mechanisms

whose outcomes only depend on r. Let:

r ∼ Gj with positive density gj on [rj, r̄j].

Social preferences can also be expressed as a function of r:

µEB

EB

[vM |r]

| {z }

λB(r)

xB

K · r + xB

M

| {z }

UB(r)

+ ES

ES

[vM |r]

| {z }

λS(r)

xS

K · r + xS

M

| {z }

US(r)

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-41-320.jpg)

![Framework – some observations

Individual preferences depend only on the rate of substitution:

r =

vK

vM

.

It will turn out that this implies that it is wlog to consider mechanisms

whose outcomes only depend on r. Let:

r ≡ vK/vM ∼ Gj with positive density gj on [rj, r̄j].

Social preferences can also be expressed as a function of r:

TS(Λ) = µ

Z r̄B

rB

λB(r)UB(r)dGB(r) +

Z r̄S

rS

λS(r)US(r)dGS(r).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-42-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – seller side

Problem: Choose a price pS to maximize seller welfare while buying

quantity Q and not exceeding a budget of R (where R QG−1

S (Q)).

max

pS≥G−1

S (Q)

(

Q

GS(pS)

Z pS

rS

λS(r)(pS − r)dGS(r) + ΛS(R − pSQ)

)

,

where ΛS = ES[vM ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-56-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – seller side

Problem: Choose a price pS to maximize seller welfare while buying

quantity Q and not exceeding a budget of R (where R QG−1

S (Q)).

max

pS≥G−1

S (Q)

(

Q

GS(pS)

Z pS

rS

λS(r)(pS − r)dGS(r) + ΛS(R − pSQ)

)

,

where ΛS = ES[vM ].

We will refer to the price pC

S = G−1

S (Q) as the competitive price;

Any price pS pC

S leads to rationing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-57-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – seller side

Intuition: There are three effects associated with raising the price pS

above the competitive level pC

S :

1 Allocative efficiency is reduced ↓

2 The mechanism uses up more money leaving a smaller amount

R − pSQ to be redistributed as a lump-sum transfer to all sellers ↓

3 Sellers that sell receive a higher price ↑

Consider the net redistribution effect 2+3:

−ΛS + ES

[λS(r)|r ≤ pS]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-68-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – seller side

Intuition: There are three effects associated with raising the price pS

above the competitive level pC

S :

1 Allocative efficiency is reduced ↓

2 The mechanism uses up more money leaving a smaller amount

R − pSQ to be redistributed as a lump-sum transfer to all sellers ↓

3 Sellers that sell receive a higher price ↑

Consider the net redistribution effect 2+3:

−ΛS + ES

[λS(r)|r ≤ pS] ≥ 0 ↑](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-69-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – seller side

Intuition: There are three effects associated with raising the price pS

above the competitive level pC

S :

1 Allocative efficiency is reduced ↓

2 The mechanism uses up more money leaving a smaller amount

R − pSQ to be redistributed as a lump-sum transfer to all sellers ↓

3 Sellers that sell receive a higher price ↑

Consider the net redistribution effect 2+3:

−ΛS + ES

[λS(r)|r ≤ pS] ≥ 0 ↑

This net effect must be stronger than the negative effect 1 to justify

rationing:

High seller-side inequality;

Low volume of trade: Q Q̄.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-70-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – buyer side

Problem: Choose a price pB to maximize buyer welfare while selling

quantity Q and raising a revenue of R (where R QG−1

B (1 − Q)).

max

pB≤G−1

B (1−Q)

Q

1 − GB(pB)

Z r̄B

pB

λB(r)(r − pB)dGB(r) + ΛB(pBQ − R)

.

where ΛB = EB[vM ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-73-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – buyer side

Problem: Choose a price pB to maximize buyer welfare while selling

quantity Q and raising a revenue of R (where R QG−1

B (1 − Q)).

max

pB≤G−1

B (1−Q)

Q

1 − GB(pB)

Z r̄B

pB

λB(r)(r − pB)dGB(r) + ΛB(pBQ − R)

.

where ΛB = EB[vM ].

We will refer to the price pC

B = G−1

B (1 − Q) as the competitive price;

Any price pB pC

B leads to rationing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-74-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – buyer side

Intuition: There are three effects associated with lowering the price pB

below the competitive level pC

B:

1 Allocative efficiency is reduced ↓

2 The mechanism generates less revenue pBQ − R that can be

redistributed as a lump-sum transfer to all buyers ↓

3 Buyers that buy pay a lower price ↑

Consider the net redistribution effect 2+3:

−ΛB + EB

[λB(r)|r ≥ pB]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-81-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – buyer side

Intuition: There are three effects associated with lowering the price pB

below the competitive level pC

B:

1 Allocative efficiency is reduced ↓

2 The mechanism generates less revenue pBQ − R that can be

redistributed as a lump-sum transfer to all buyers ↓

3 Buyers that buy pay a lower price ↑

Consider the net redistribution effect 2+3:

−ΛB + EB

[λB(r)|r ≥ pB] ≤ 0 ↓](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-82-320.jpg)

![Single-price mechanisms – buyer side

Intuition: There are three effects associated with lowering the price pB

below the competitive level pC

B:

1 Allocative efficiency is reduced ↓

2 The mechanism generates less revenue pBQ − R that can be

redistributed as a lump-sum transfer to all buyers ↓

3 Buyers that buy pay a lower price ↑

Consider the net redistribution effect 2+3:

−ΛB + EB

[λB(r)|r ≥ pB] ≤ 0 ↓

The net redistribution effect is negative!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-83-320.jpg)

![Two-price mechanisms – buyer side

Low buyer-side inequality ⇐⇒ λB(rB) ≤ 2ΛB.

Proposition

When buyer-side inequality is low, it is optimal not to offer the low price

pL

B and to choose pH

B = pC

B.

When buyer-side inequality is high, there exists Q ∈ (0, 1] such that

Rationing at the low price is optimal when Q Q;

Setting pH

B = pC

B (and not offering the low price pL

B) is optimal for

Q ≤ Q.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-94-320.jpg)

![Two-price mechanisms – buyer side

Low buyer-side inequality ⇐⇒ λB(rB) ≤ 2ΛB.

Proposition

When buyer-side inequality is low, it is optimal not to offer the low price

pL

B and to choose pH

B = pC

B.

When buyer-side inequality is high, there exists Q ∈ (0, 1] such that

Rationing at the low price is optimal when Q Q;

Setting pH

B = pC

B (and not offering the low price pL

B) is optimal for

Q ≤ Q.

This is in fact the optimal mechanism overall!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-95-320.jpg)

![Two-price mechanisms – buyer side

Intuition: This time rationing (a discounted price) is offered to buyers

with relatively low types r ∈ [pL

B, rδ], so that it is possible that the net

redistribution effect is positive:

−ΛB](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-96-320.jpg)

![Two-price mechanisms – buyer side

Intuition: This time rationing (a discounted price) is offered to buyers

with relatively low types r ∈ [pL

B, rδ], so that it is possible that the net

redistribution effect is positive:

−ΛB + EB

[λB(r)| r ∈ [pL

B, rδ]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-97-320.jpg)

![Two-price mechanisms – buyer side

Intuition: This time rationing (a discounted price) is offered to buyers

with relatively low types r ∈ [pL

B, rδ], so that it is possible that the net

redistribution effect is positive:

−ΛB + EB

[λB(r)| r ∈ [pL

B, rδ]] ≥ 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-98-320.jpg)

![Two-price mechanisms – buyer side

Intuition: This time rationing (a discounted price) is offered to buyers

with relatively low types r ∈ [pL

B, rδ], so that it is possible that the net

redistribution effect is positive:

−ΛB + EB

[λB(r)| r ∈ [pL

B, rδ]] ≥ 0 ↑](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-99-320.jpg)

![Two-price mechanisms – buyer side

Intuition: This time rationing (a discounted price) is offered to buyers

with relatively low types r ∈ [pL

B, rδ], so that it is possible that the net

redistribution effect is positive:

−ΛB + EB

[λB(r)| r ∈ [pL

B, rδ]] ≥ 0 ↑

This net effect must be stronger than the negative effect on allocative

efficiency to justify rationing:

High buyer-side inequality;

High volume of trade: Q Q.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-100-320.jpg)

![General Framework

A designer chooses a mechanism to allocate a unit mass of objects to

a unit mass of agents.

Each object has quality q ∈ [0, 1], q is distributed acc. to cdf F.

Each agent is characterized by a type (i, r, λ), where:

i is an observable label, i ∈ I (finite);

r is an unobserved willingness to pay (for quality), r ∈ R+;

λ is an unobserved social welfare weight, λ ∈ R+;

The type distribution is known to the designer.

If (i, r, λ) gets a good with quality q and pays t, her utility is qr − t,

while her contribution to social welfare is λ(qr − t)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-120-320.jpg)

![General Framework

The designer has access to arbitrary (direct) allocation mechanisms

(Γ, T) where Γ(q|i, r, λ) is the probability that (i, r, λ) gets a good with

quality q or less, and T(i, r, λ) is the associated payment, subject to:

Feasibility: E(i,r,λ) [Γ(q|i, r, λ)] ≥ F(q), ∀q ∈ [0, 1];

IC constraint: Each agent (i, r, λ) reports (r, λ) truthfully;

IR constraint: U(i, r, λ) ≡ r

R

qdΓ(q|i, r, λ) − T(i, r, λ) ≥ 0;

Non-negative transfers: T(i, r, λ) ≥ 0, ∀(i, r, λ).

The designer maximizes, for some constant α ≥ 0, a weighted sum of

revenue and agents’ utilities:

E(i,r,λ) [αT(i, r, λ) + λU(i, r, λ)] .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-121-320.jpg)

![Framework

Lemma

It is optimal for the designer to condition the allocation and transfers only

on agents’ labels i and WTP r.

Let Vi(r) be the expected per-unit-of-quality social benefit from allocating

a good to an agent with WTP r in group i in an IC mechanism.

With redistributive preferences:

Vi(r) = Λi(r) ·

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

utility

+ α ·

r −

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

revenue

where Λi(r) = Er̃∼Gi [ λ | r̃ ≥ r, i].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-135-320.jpg)

![Framework

Lemma

It is optimal for the designer to condition the allocation and transfers only

on agents’ labels i and WTP r.

Let Vi(r) be the expected per-unit-of-quality social benefit from allocating

a good to an agent with WTP r in group i in an IC mechanism.

With redistributive preferences:

Vi(r) = Λi(r) ·

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

utility

+ α ·

r −

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

revenue

where Λi(r) = Er̃∼Gi [ λ | r̃ ≥ r, i].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-136-320.jpg)

![Framework

Economic idea:

The designer assesses the “need” of agents by estimating the unobserved

welfare weights based on the observable (label i) and elicitable (wtp r)

information:

Λi(r) = Er̃∼Gi [ λ | r̃ ≥ r, i].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-137-320.jpg)

![Framework

Economic idea:

The designer assesses the “need” of agents by estimating the unobserved

welfare weights based on the observable (label i) and elicitable (wtp r)

information:

Λi(r) = Er̃∼Gi [ λ | r̃ ≥ r, i].

Consequence:

The optimal allocation depends on the statistical correlation of labels

and willingness to pay with the unobserved social welfare weights.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-138-320.jpg)

![Framework

Economic idea:

The designer assesses the “need” of agents by estimating the unobserved

welfare weights based on the observable (label i) and elicitable (wtp r)

information:

Λi(r) = Er̃∼Gi [ λ | r̃ ≥ r, i].

Consequence:

The optimal allocation depends on the statistical correlation of labels

and willingness to pay with the unobserved social welfare weights.

Correlation is likely to be negative (however, the direction and strength

depend on the market context!)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-139-320.jpg)

![Derivation of Optimal Mechanism

1 Objects are allocated “across” groups: F is split into I cdfs F⋆

i ;

2 Objects are allocated “within” groups: For each label i, the objects

F⋆

i are allocated optimally to agents in group i.

Observation: Only expected quality, Qi(r), matters for payoffs.

Within a group, agents are partitioned into intervals according to WTP,

with either the “market” or “non-market” allocation in each interval:

Market allocation: assortative matching between WTP and quality

Qi(r) = (F⋆

i )−1

(Gi(r)), ∀r ∈ [a, b];](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-153-320.jpg)

![Derivation of Optimal Mechanism

1 Objects are allocated “across” groups: F is split into I cdfs F⋆

i ;

2 Objects are allocated “within” groups: For each label i, the objects

F⋆

i are allocated optimally to agents in group i.

Observation: Only expected quality, Qi(r), matters for payoffs.

Within a group, agents are partitioned into intervals according to WTP,

with either the “market” or “non-market” allocation in each interval:

Market allocation: assortative matching between WTP and quality

Qi(r) = (F⋆

i )−1

(Gi(r)), ∀r ∈ [a, b];

Non-market allocation: random matching between WTP and quality

Qi(r) = q̄, ∀r ∈ [a, b].

Details](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-154-320.jpg)

![Economic Implications

Assuming differentiability, the condition for using a non-market mechanism

around type r in group i becomes

Λ′

i(r)

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

+ α + (Λi(r) − α)

d

dr

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

0,

where recall that Λi(r) = Er̃∼Gi [ λ | r̃ ≥ r, i].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-185-320.jpg)

![Economic Implications

Assuming differentiability, the condition for using a non-market mechanism

around type r in group i becomes

Λ′

i(r)

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

+ α + (Λi(r) − α)

d

dr

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

0,

where recall that Λi(r) = Er̃∼Gi [ λ | r̃ ≥ r, i].

Thus, non-market allocation is optimal if willingness to pay is strongly

(negatively) correlated with the unobserved social welfare weights.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-186-320.jpg)

![Economic Implications

Assuming differentiability, the condition for using a non-market mechanism

around type r in group i becomes

Λ′

i(r)

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

+ α + (Λi(r) − α)

d

dr

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

0,

where recall that Λi(r) = Er̃∼Gi [ λ | r̃ ≥ r, i].

Thus, non-market allocation is optimal if willingness to pay is strongly

(negatively) correlated with the unobserved social welfare weights.

This is more likely to hold when:

The designer has strong redistributive preferences (dispersion in λ’s);

The good being allocated is relatively expensive and everyone needs it;

The label i is not very informative about λ.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-187-320.jpg)

![Extensions and Future Work

Allocative externalities =⇒ vaccine allocation (ADK + Eric Budish)

Vi(r) = Λi(r) ·

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

utility

+ α ·

r −

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

revenue

+ E [Tex|i, r]

| {z }

externality

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-217-320.jpg)

![Extensions and Future Work

Allocative externalities =⇒ vaccine allocation (ADK + Eric Budish)

Vi(r) = Λi(r) ·

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

utility

+ α ·

r −

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

revenue

+ E [Tex|i, r]

| {z }

externality

.

Pricing versus Rationing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-218-320.jpg)

![Extensions and Future Work

Allocative externalities =⇒ vaccine allocation (ADK + Eric Budish)

Vi(r) = Λi(r) ·

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

utility

+ α ·

r −

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

revenue

+ E [Tex|i, r]

| {z }

externality

.

Pricing versus Rationing versus Queuing (ADK + Shengwu Li)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-219-320.jpg)

![Extensions and Future Work

Allocative externalities =⇒ vaccine allocation (ADK + Eric Budish)

Vi(r) = Λi(r) ·

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

utility

+ α ·

r −

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

revenue

+ E [Tex|i, r]

| {z }

externality

.

Pricing versus Rationing versus Queuing (ADK + Shengwu Li)

vK · xK + vM · xM − vQ · xQ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-220-320.jpg)

![Extensions and Future Work

Allocative externalities =⇒ vaccine allocation (ADK + Eric Budish)

Vi(r) = Λi(r) ·

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

utility

+ α ·

r −

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

revenue

+ E [Tex|i, r]

| {z }

externality

.

Pricing versus Rationing versus Queuing (ADK + Shengwu Li)

vK · xK + vM · xM − vQ · xQ

Other on-going projects:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-221-320.jpg)

![Extensions and Future Work

Allocative externalities =⇒ vaccine allocation (ADK + Eric Budish)

Vi(r) = Λi(r) ·

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

utility

+ α ·

r −

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

revenue

+ E [Tex|i, r]

| {z }

externality

.

Pricing versus Rationing versus Queuing (ADK + Shengwu Li)

vK · xK + vM · xM − vQ · xQ

Other on-going projects:

▶ Application to congestion pricing;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-222-320.jpg)

![Extensions and Future Work

Allocative externalities =⇒ vaccine allocation (ADK + Eric Budish)

Vi(r) = Λi(r) ·

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

utility

+ α ·

r −

1 − Gi(r)

gi(r)

| {z }

revenue

+ E [Tex|i, r]

| {z }

externality

.

Pricing versus Rationing versus Queuing (ADK + Shengwu Li)

vK · xK + vM · xM − vQ · xQ

Other on-going projects:

▶ Application to congestion pricing;

▶ Comparison of screening devices.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-223-320.jpg)

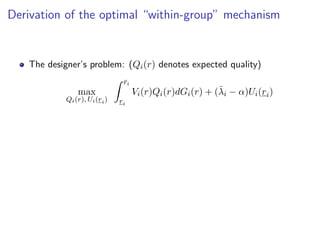

![Derivation of the optimal “within-group” mechanism

The designer’s problem is

max

Ψi

Z 1

0

Vi(t)

z }| {

Z 1

t

Vi(G−1

i (x))dx + max{0, λ̄i − α}ri1{t=0}

dΨi(t)

s.t. Ψi ≻MPS

F−1

i

Agents are partitioned into intervals according to WTP:

▶ Market allocation: assortative matching between WTP and quality

Qi(r) = F−1

i (Gi(r)), ∀r ∈ [a, b];

Back](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-266-320.jpg)

![Derivation of the optimal “within-group” mechanism

The designer’s problem is

max

Ψi

Z 1

0

Vi(t)

z }| {

Z 1

t

Vi(G−1

i (x))dx + max{0, λ̄i − α}ri1{t=0}

dΨi(t)

s.t. Ψi ≻MPS

F−1

i

Agents are partitioned into intervals according to WTP:

▶ Market allocation: assortative matching between WTP and quality

Qi(r) = F−1

i (Gi(r)), ∀r ∈ [a, b];

▶ Non-market allocation: random matching between WTP and quality

Qi(r) = q̄, ∀r ∈ [a, b].

Back](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-267-320.jpg)

![Derivation of the optimal “within-group” mechanism

The designer’s problem is

max

Ψi, F̃i

Z 1

0

Vi(t)

z }| {

Z 1

t

Vi(G−1

i (x))dx + max{0, λ̄i − α}ri1{t=0}

dΨi(t)

s.t. Ψi ≻MPS

F̃−1

i ≻FOSD

F−1

i

Agents are partitioned into intervals according to WTP:

▶ Market allocation: assortative matching between WTP and quality

Qi(r) = F−1

i (Gi(r)), ∀r ∈ [a, b];

▶ Non-market allocation: random matching between WTP and quality

Qi(r) = q̄, ∀r ∈ [a, b].

Back](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-220825151659-0811a3d9/85/Redistribution-through-Markets-268-320.jpg)