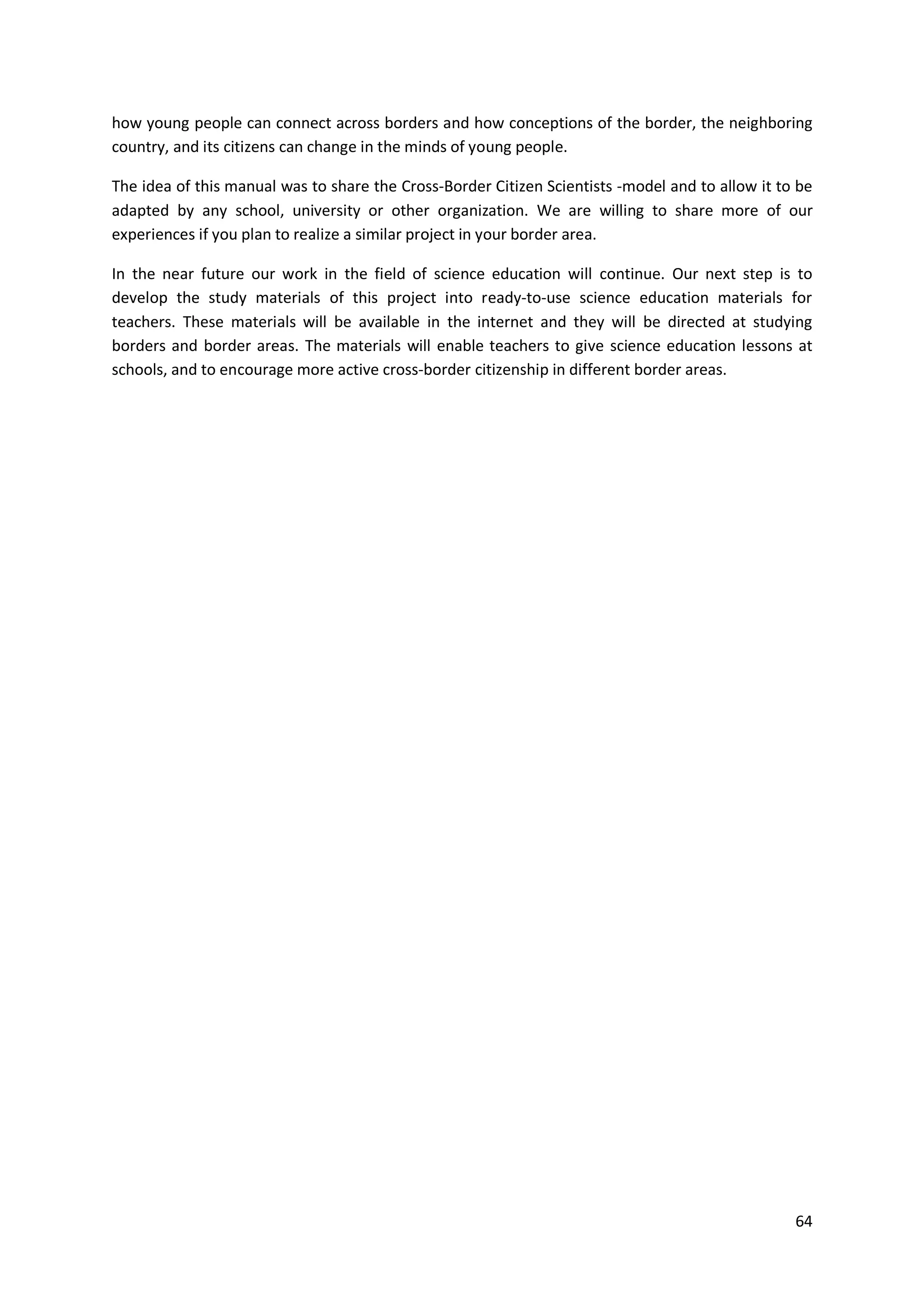

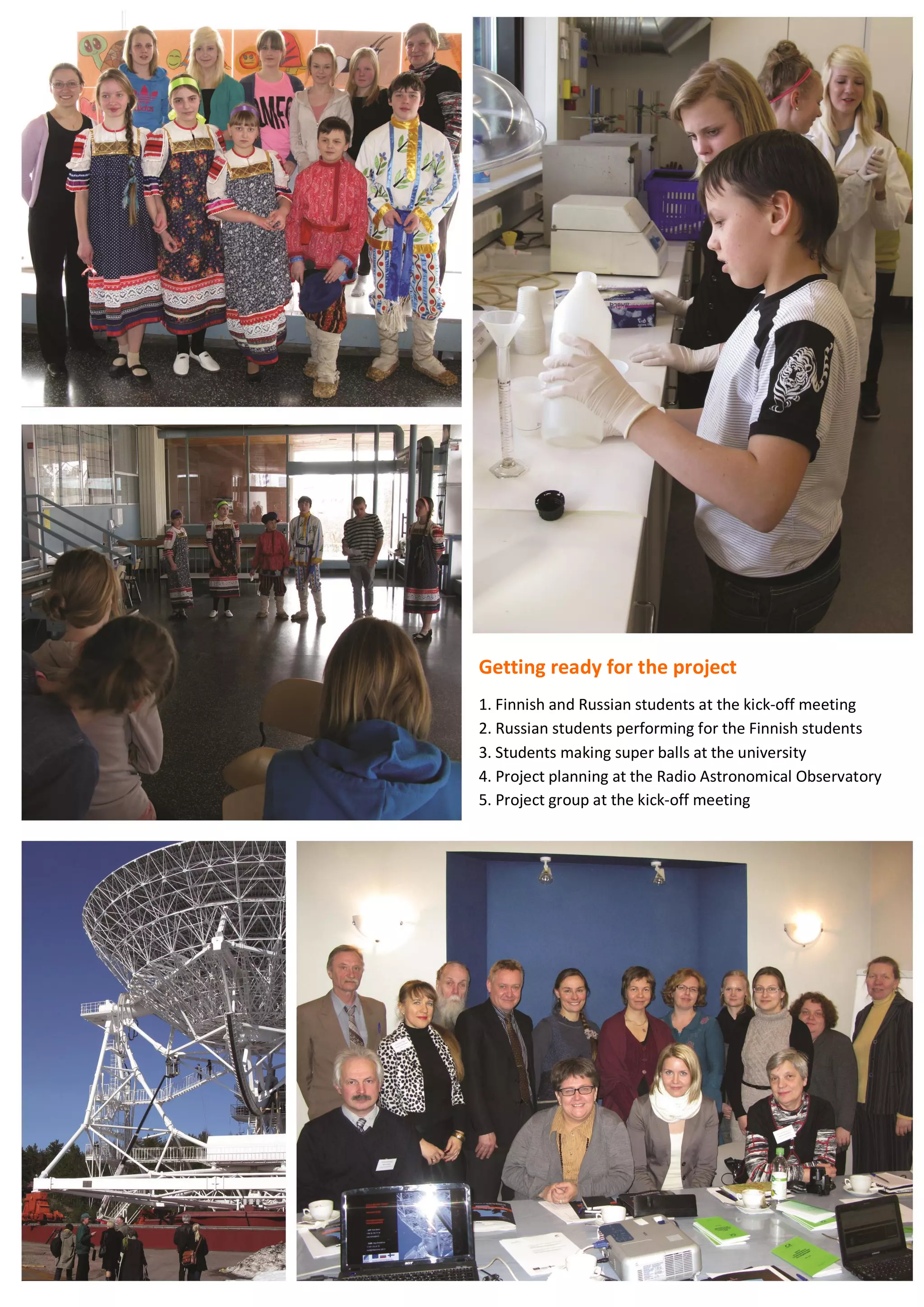

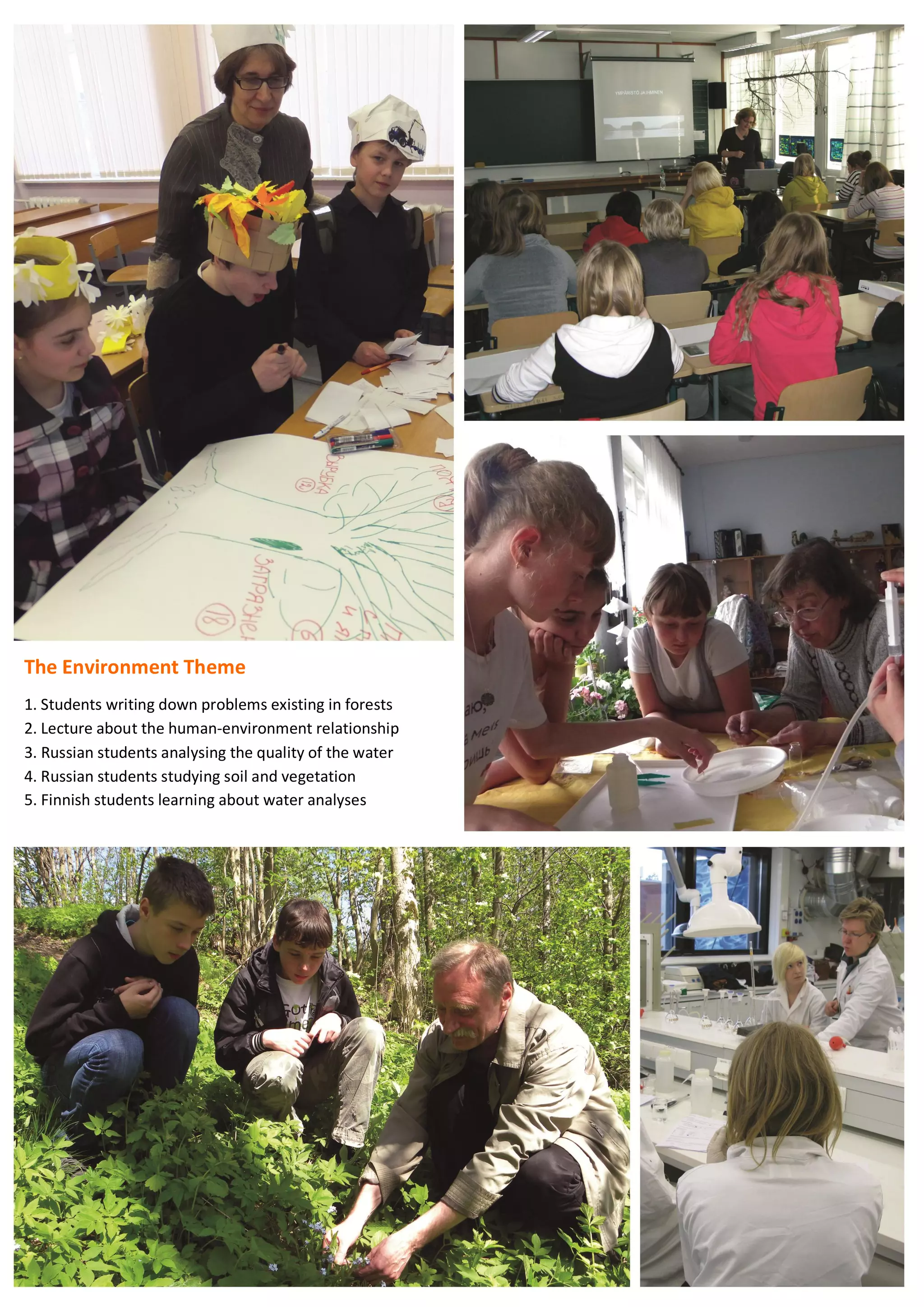

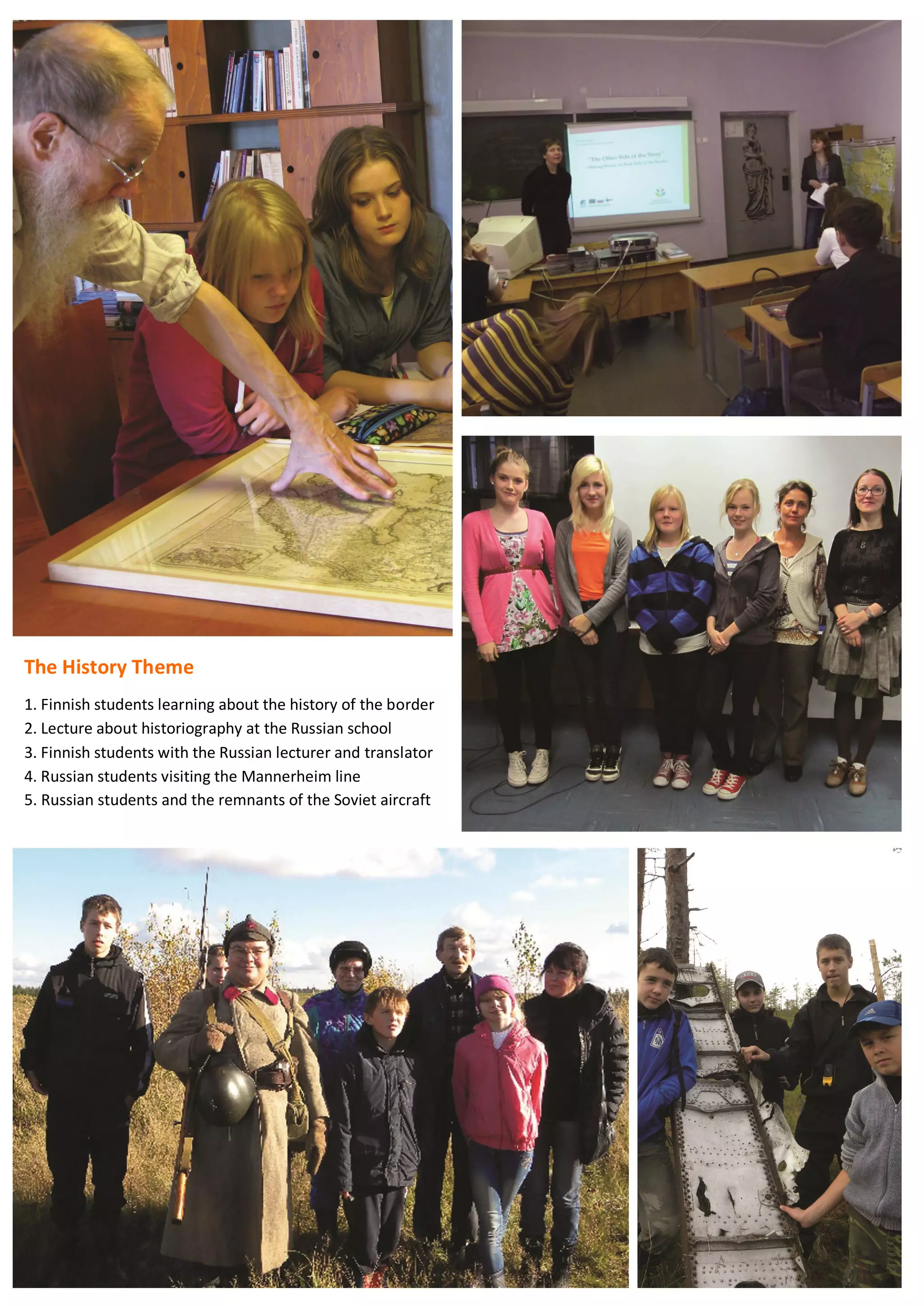

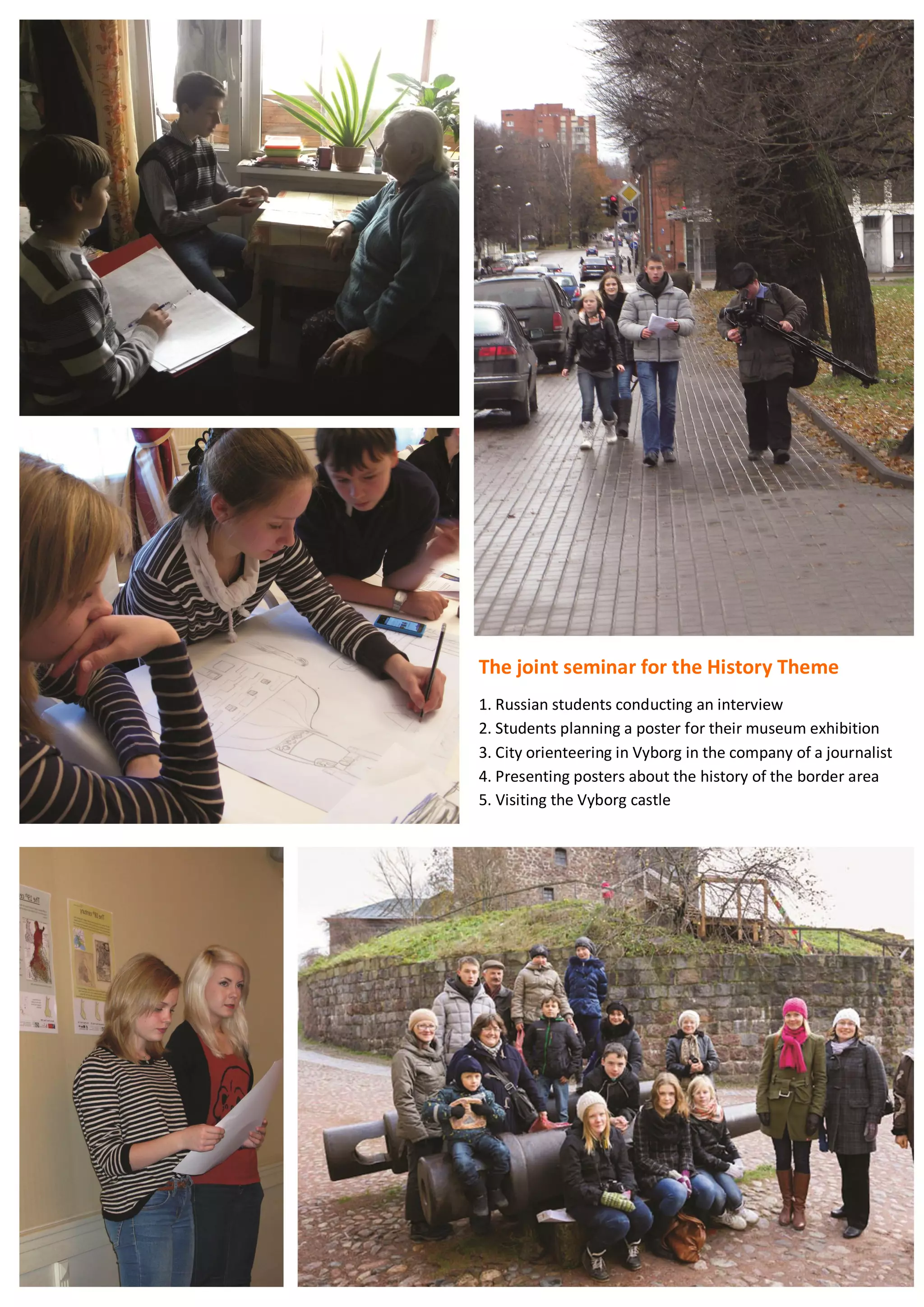

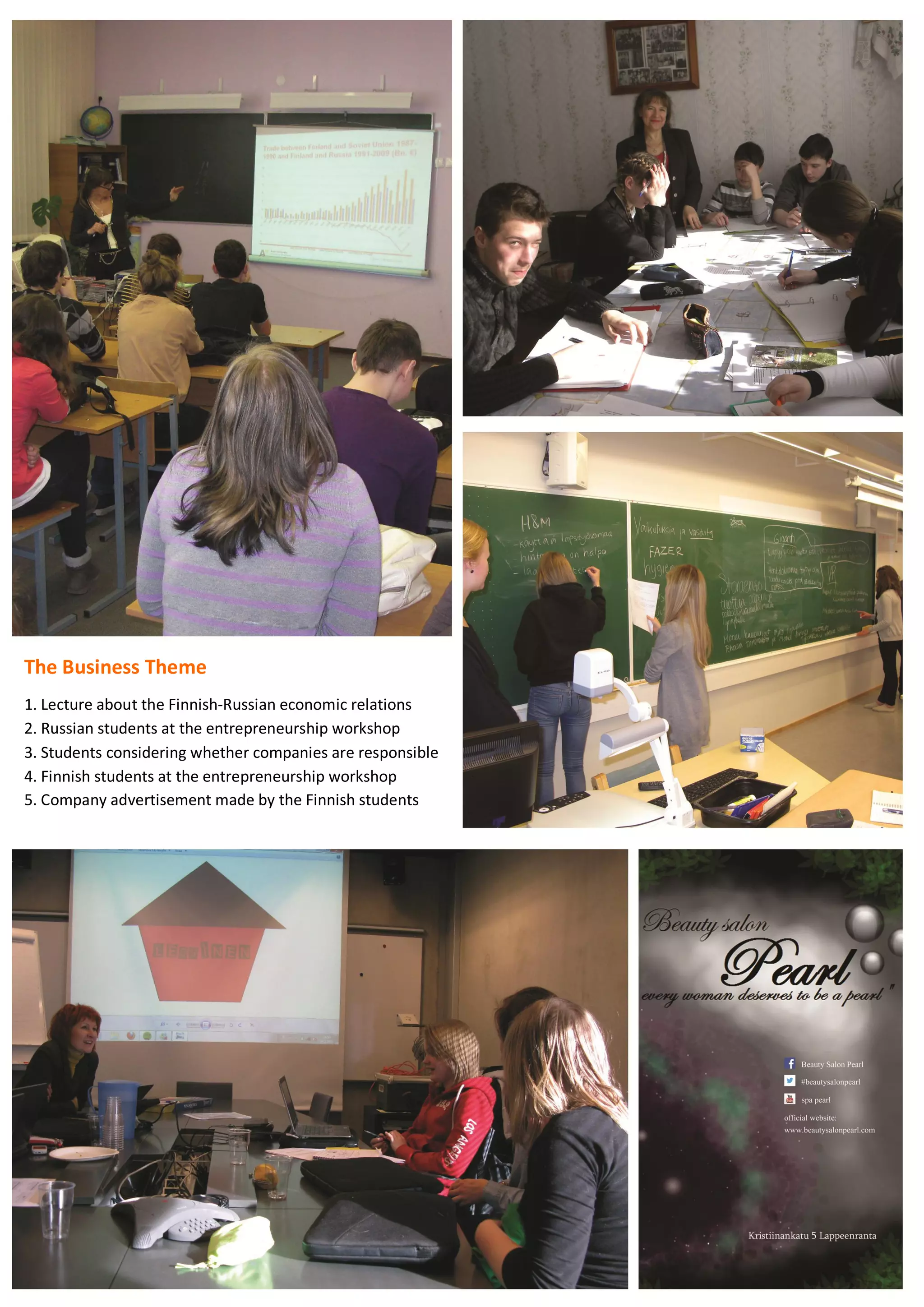

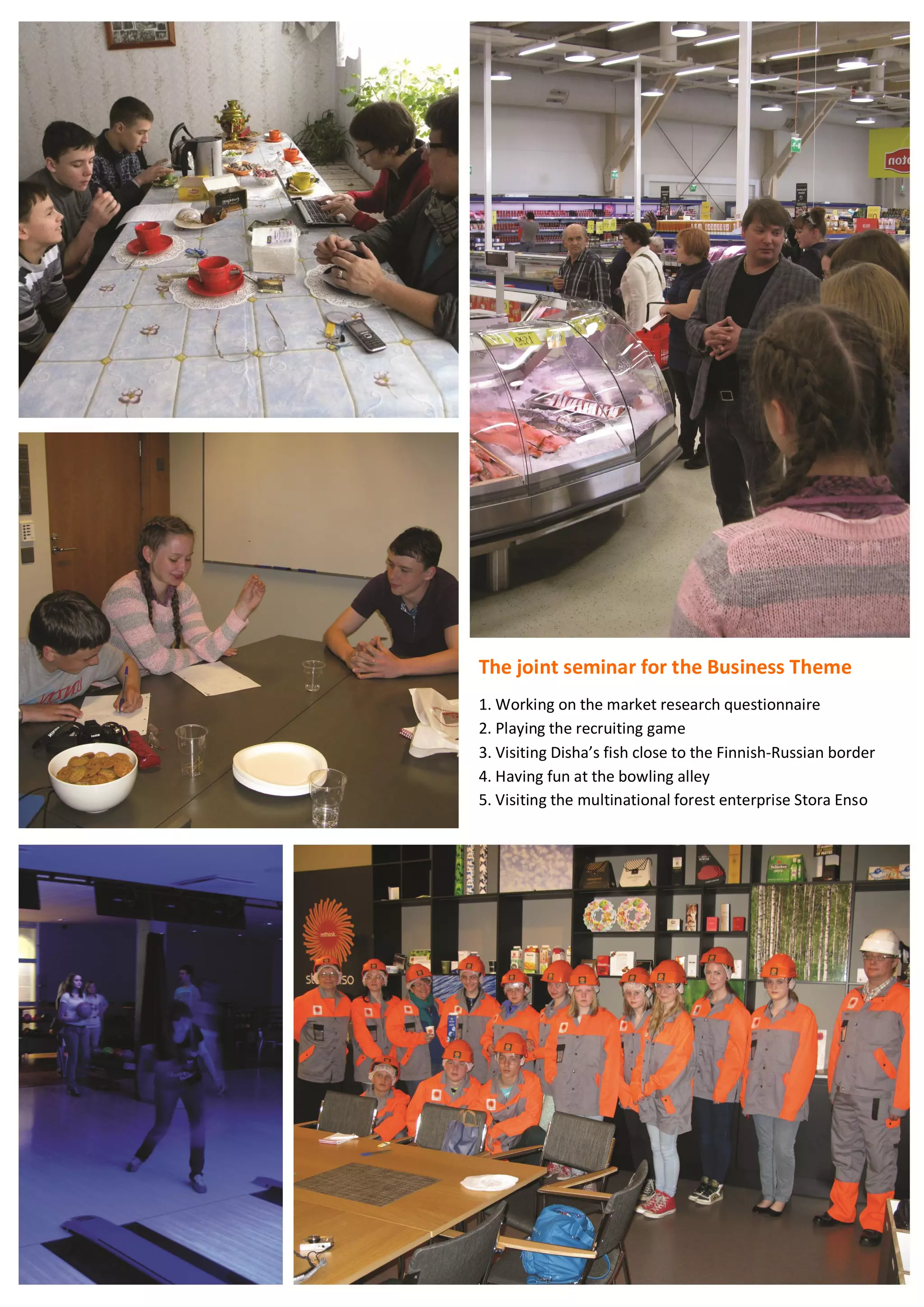

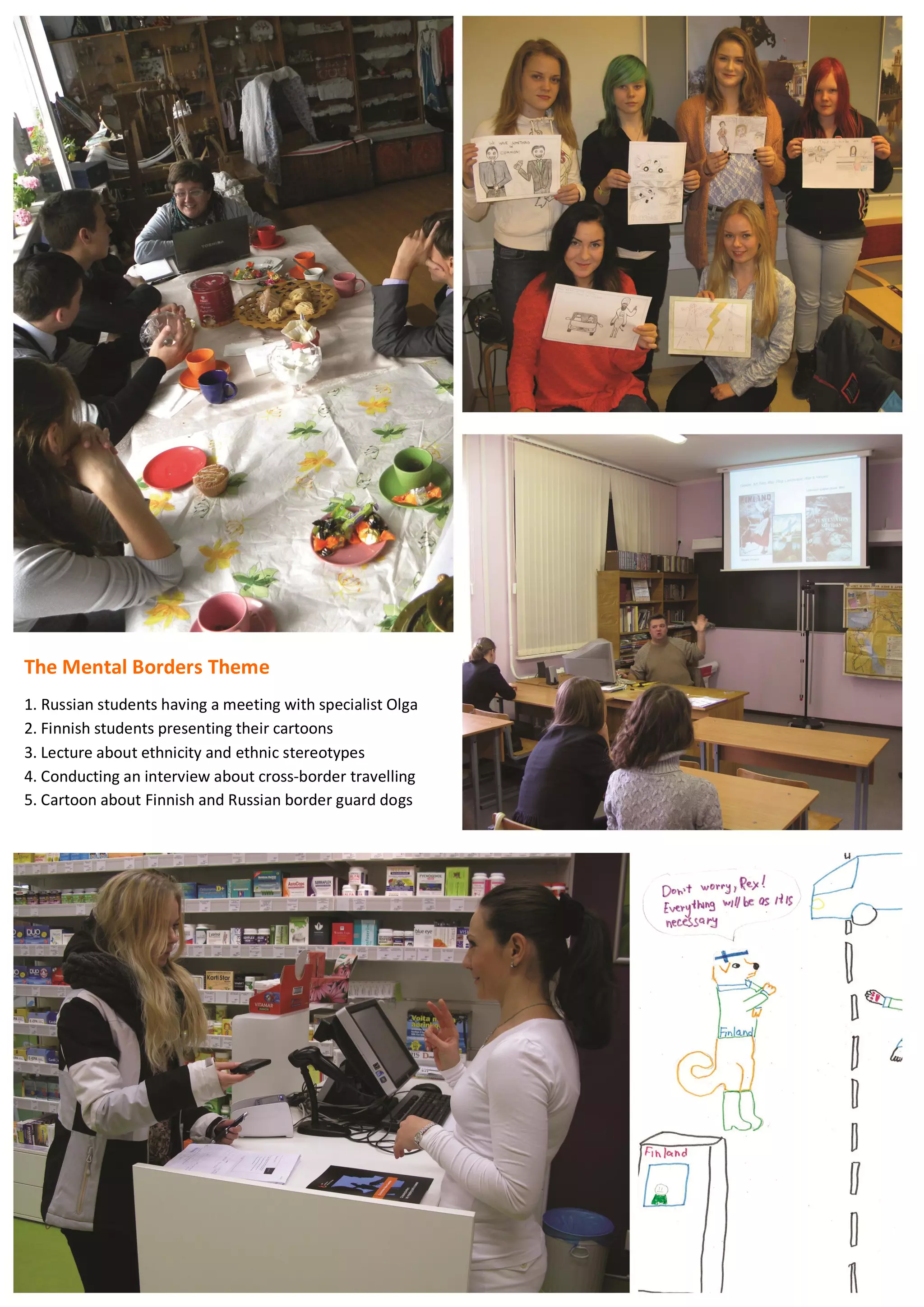

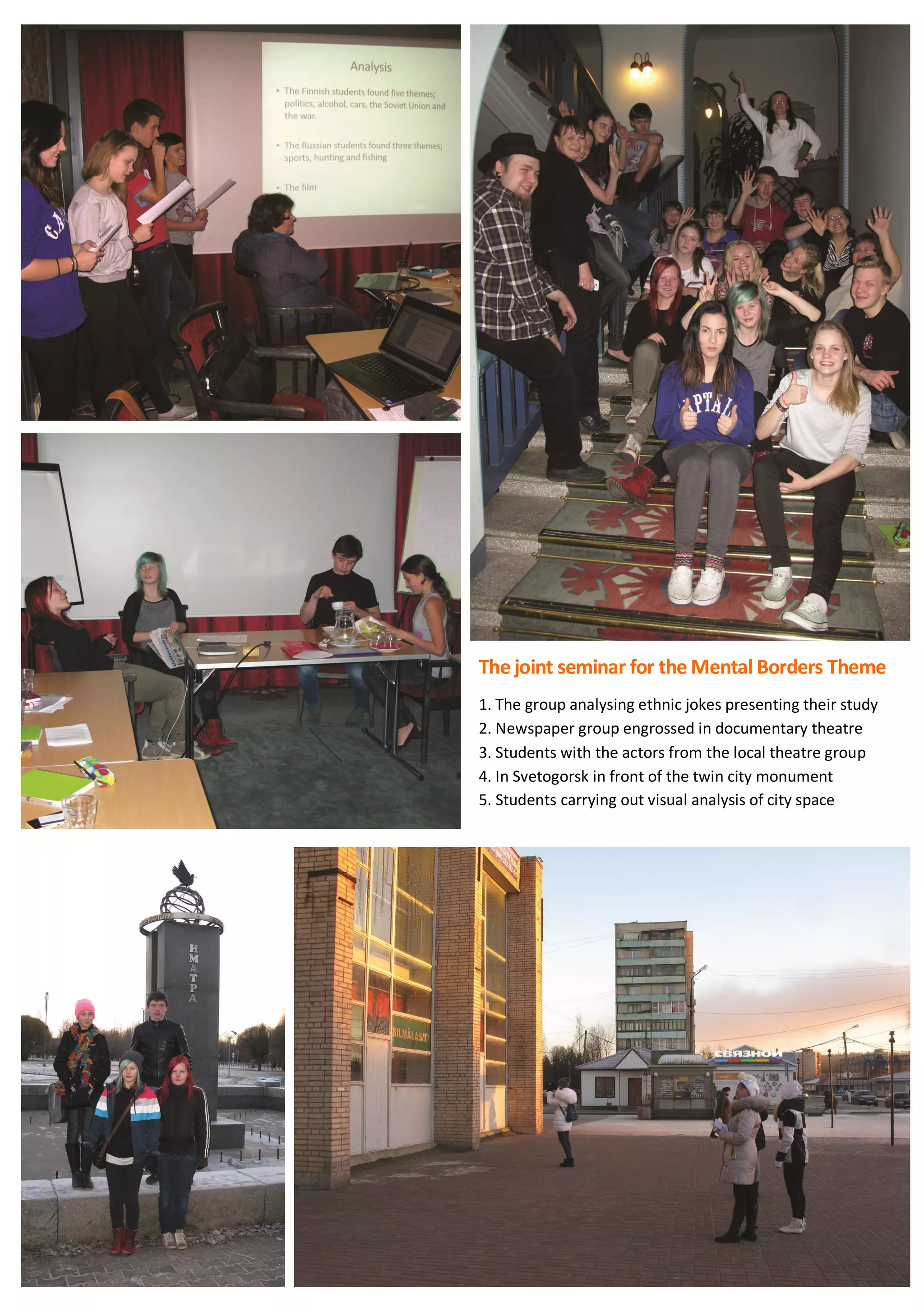

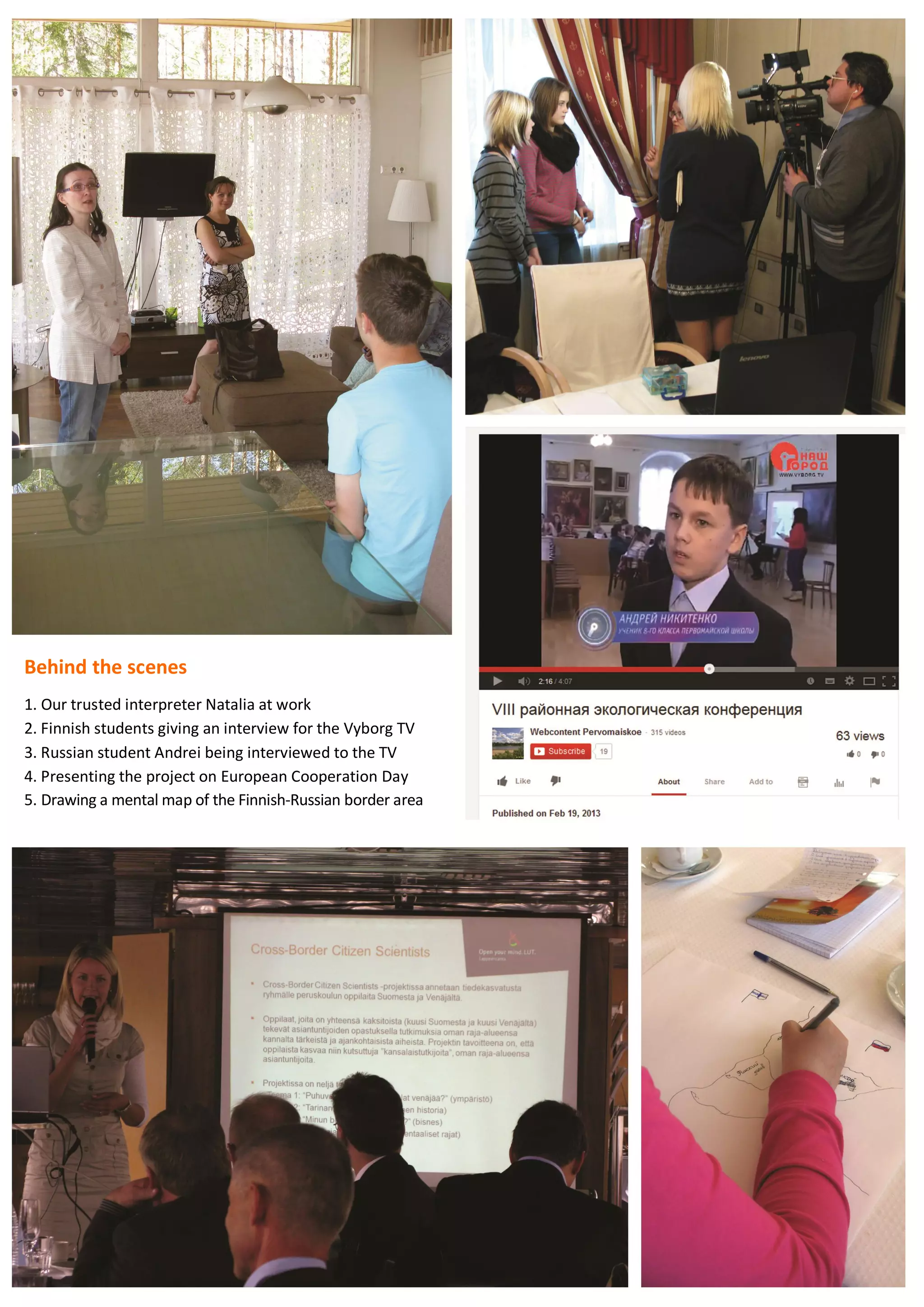

The document introduces the Cross-Border Citizen Scientists project, which aimed to provide science education to young people on both sides of the Finnish-Russian border. The project involved 12 students from Finland and Russia who studied the border area through four themes: environment, history, business, and mental borders. For each theme, students attended lectures, participated in in-depth study periods with specialists, held joint seminars to present findings, and taught other students what they learned. The goal was for the young "citizen scientists" to gain first-hand knowledge of the opportunities and challenges of the border area through conducting their own small research projects. The manual provides details on implementing a similar cross-border youth education project in other border regions.

![3

Johdanto

Raja-alueet ovat paikkoja, joissa kansakunnat ja kulttuurit kohtaavat. On sanottu, että rajat ovat sekä

erottavia että yhdistäviä tekijöitä, riippuen siitä miten niihin suhtaudutaan. Ne erottavat valtiot,

kansat ja kulttuurit toisistaan, mutta samaan aikaan ne mahdollistavat ihmisten ja kulttuurien

kohtaamisen ja sekoittumisen. Aluekehityksen näkökulmasta rajat nähdään yhä useammin

mahdollisuutena kuin kehityksen esteenä. Riippumatta siitä, miten rajoihin suhtaudutaan, haastavat

ne yhä paikallisia, alueellisia ja valtiollisia toimijoita. Rajayhteistyötä tarvitaan, vaikka valtioiden

välinen raja olisi suljettu, sillä esimerkiksi luonto ei pysähdy ihmisen tekemälle rajalle.

Tässä käsikirjassa esitellään toimintamalli, jonka avulla voidaan houkutella nuoria rajayhteistyön

pariin. Käsikirja perustuu ”Cross-Border Citizen Scientists” [Raja-alueen kansalaistutkijat] projektiin,

joka toteutettiin vuosina 2012–2014 Kaakkois-Suomen ja Luoteis-Venäjän raja-alueella. Projektin

rahoitti Euroopan Unionin Kaakkois-Suomi – Venäjä ENPI CBC 2007–2013 ohjelma. Projektin

tavoitteena oli myötävaikuttaa aktiivisen rajat ylittävän kansalaisuuden ja rajat ylittävien kontaktien

syntymiseen. Projektissa annettiin tiedekasvatusta nuorille molemmilla puolilla rajaa, toisin sanoen,

kahdentoista suomalaisen ja venäläisen peruskoululaisen ryhmä opetteli tekemään tutkimusta

omasta raja-alueestaan. Projekti pohjautui ajatukseen, jonka mukaan nuoret tulevat tietoisiksi raja-

alueen haasteista ja rajan tarjoamista mahdollisuuksista keräämällä alueesta omakätistä tietoa ja

tutkimalla aluetta yhdessä. Projektissa rajaa ei tarkasteltu pelkästään fyysisenä elementtinä, vaan

myös mentaalisena rakenteena, ja yritettiin vaikuttaa niihin mielikuviin ja ennakkoluuloihin, joita

nuorilla on omaa naapurimaataan ja sen asukkaita kohtaan.

”Cross-Border Citizen Scientists” projekti sai innoituksensa kansalaistieteen [citizen science]

käsitteestä. Tiedettä pidetään usein suljettujen piirien, tiedemiesten maailmana, josta

tiedemaailman ulkopuolisilla ihmisillä ei ole paljon ymmärrystä. Kansalaistieteen ideana on

houkutella tavallisia kansalaisia osallistumaan tieteelliseen tutkimukseen. Kaikkein

yksinkertaisimmillaan kansalaistiede on havaintojen ja datan keräämistä tutkijoiden käyttöön, mutta

kansalaistutkijoita voidaan myös kutsua osallistumaan tutkimuksen ajattelu- ja

analysointiprosesseihin. ”Cross-Border Citizen Scientists” projektissa nuoret oppivat tieteestä ja

pienten tutkimusprojektien tekemisestä. Nuoret eivät ottaneet osaa projektin ulkopuolisiin

tieteellisiin tutkimuksiin, vaan heillä oli omat tutkimuksensa, joissa he tarkastelivat lähiympäristöään

tieteellisten menetelmien avulla.

Projektissa oli neljä teemaa; ympäristö, historia, bisnes ja rajatutkimus (mentaaliset rajat). Jokainen

teema oli rakenteeltaan identtinen ja kesti lukukauden verran. Aluksi oppilaat osallistuivat

”teemaeksperttien” luennoille. Suomalaiset ja venäläiset tutkijat pitivät luennot ja niissä oli

yhteiskuntatieteellinen näkökulma. Seuraavaksi oppilailla oli “spesialistien” vetämä syventävä

opintojakso, jonka aikana he opiskelivat teeman aihetta ja toteuttivat pieniä tutkimusprojekteja.

Syventävän opintojakson jälkeen suomalaiset ja venäläiset oppilaat kokoontuivat yhteiseen

seminaariin, jossa he esittelivät tutkimustuloksiaan, keskustelivat, tekivät lisätehtäviä, ja vierailivat](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/826ff5f2-cb34-4b5e-a6b1-92db31b64603-150326125135-conversion-gate01/75/Project_Manual_FINAL_WEB-10-2048.jpg)