The document provides a comprehensive overview of compiler design, covering key concepts, phases, and components involved in translating high-level programming languages to machine code. It outlines essential topics like lexical analysis, syntax analysis, semantic analysis, intermediate code generation, code optimization, and code generation along with their roles and challenges. Additionally, it describes various language processing systems and applications of compiler technology, including hardware synthesis and binary translation.

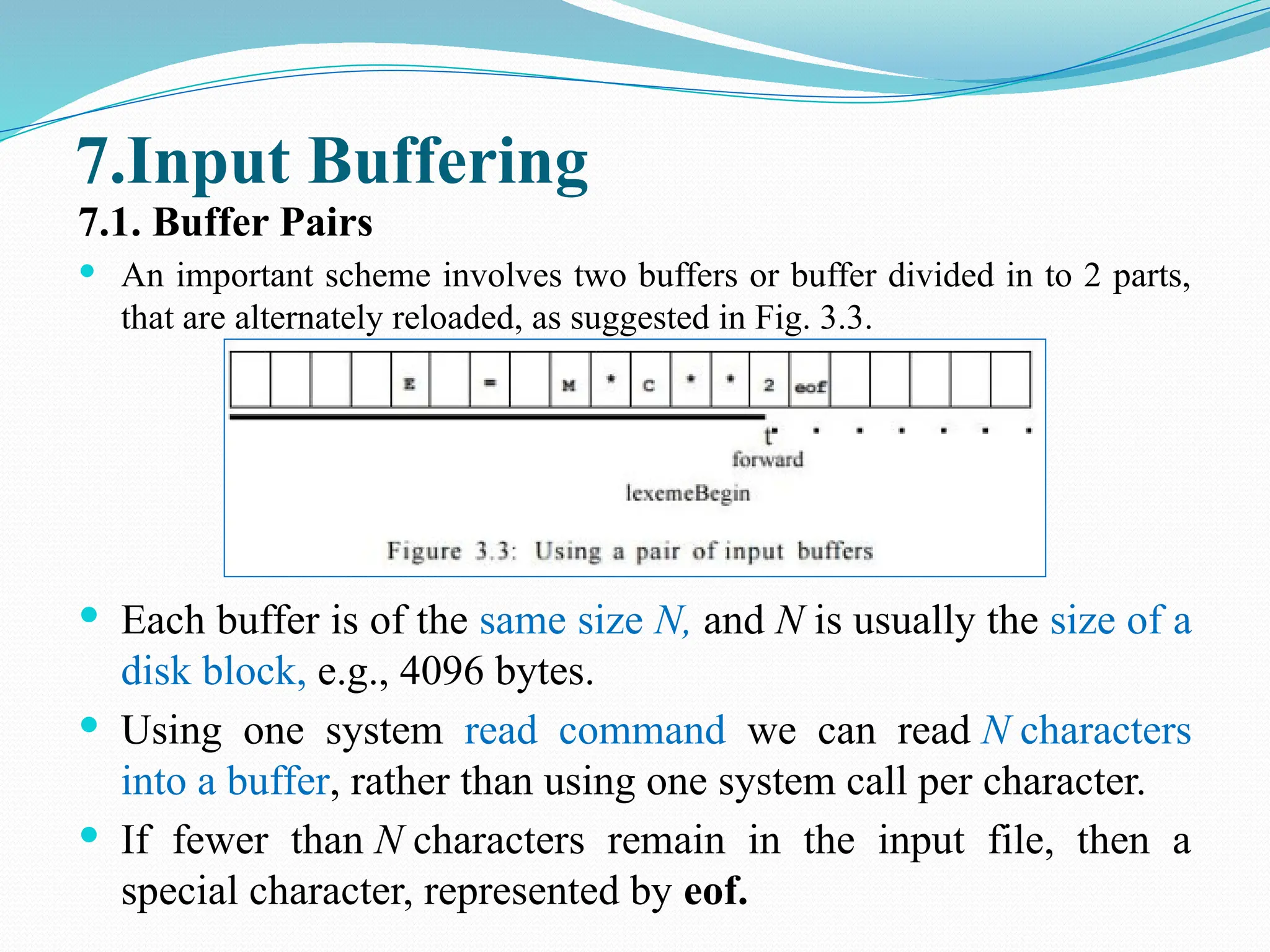

![Optimized compiler includes

Type Checking

A=b+c

A[50]

Bounds Checking(array out of bounds,

buffer overflow)

Memory – Management Tools(garbage)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptcd-240917100831-401ac4fa/75/ppt_cd-pptx-ppt-on-phases-of-compiler-of-jntuk-syllabus-58-2048.jpg)

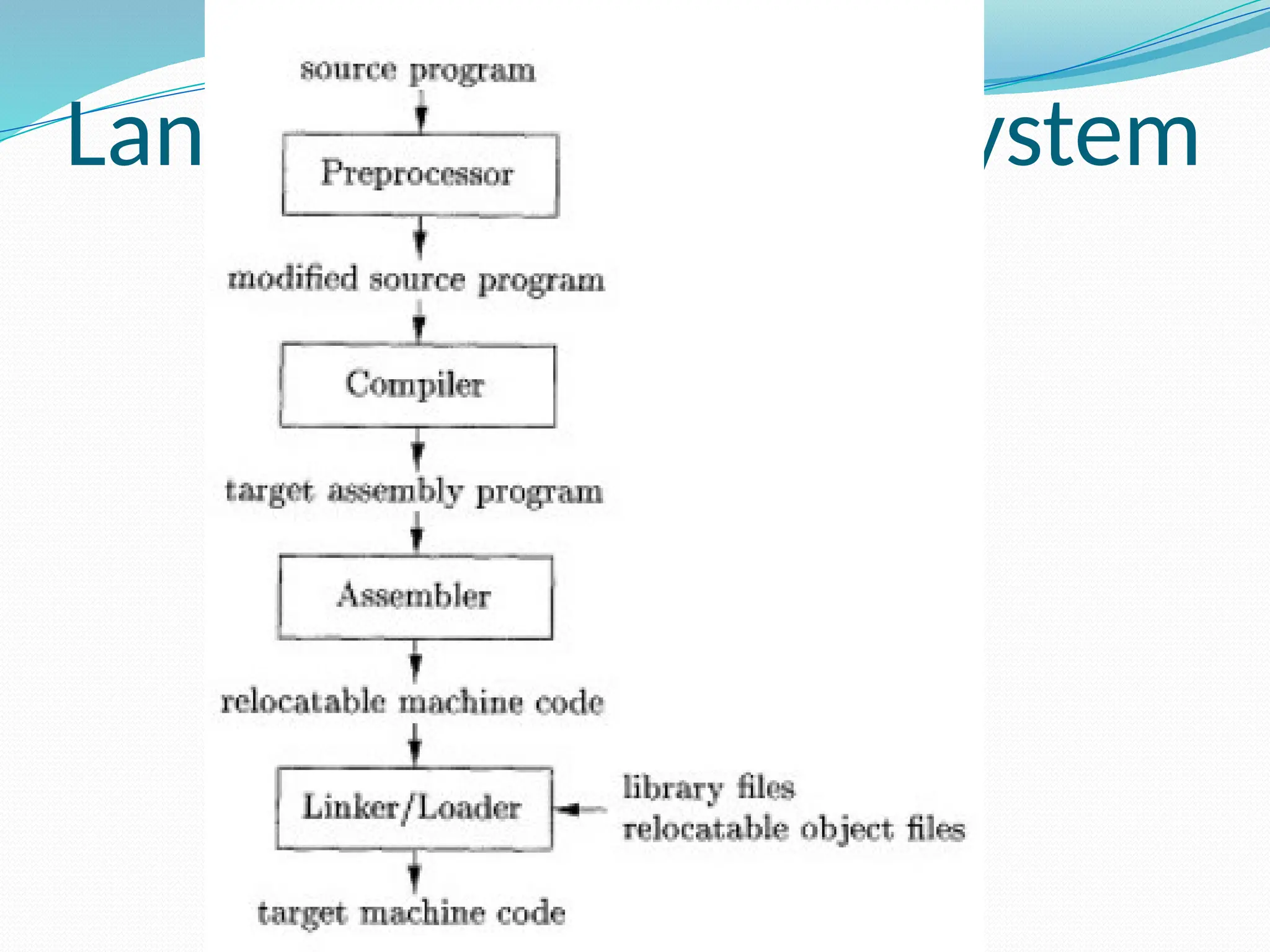

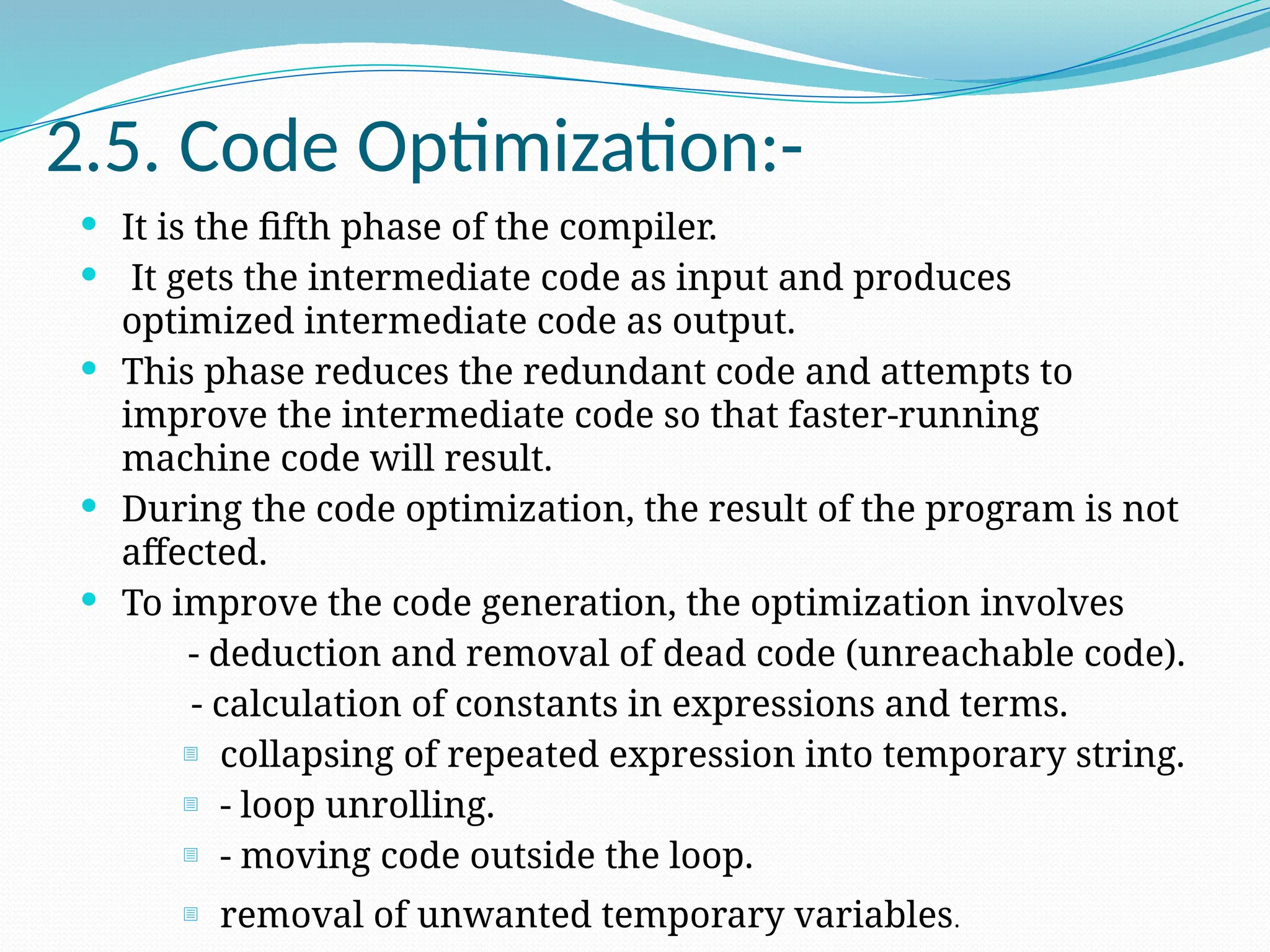

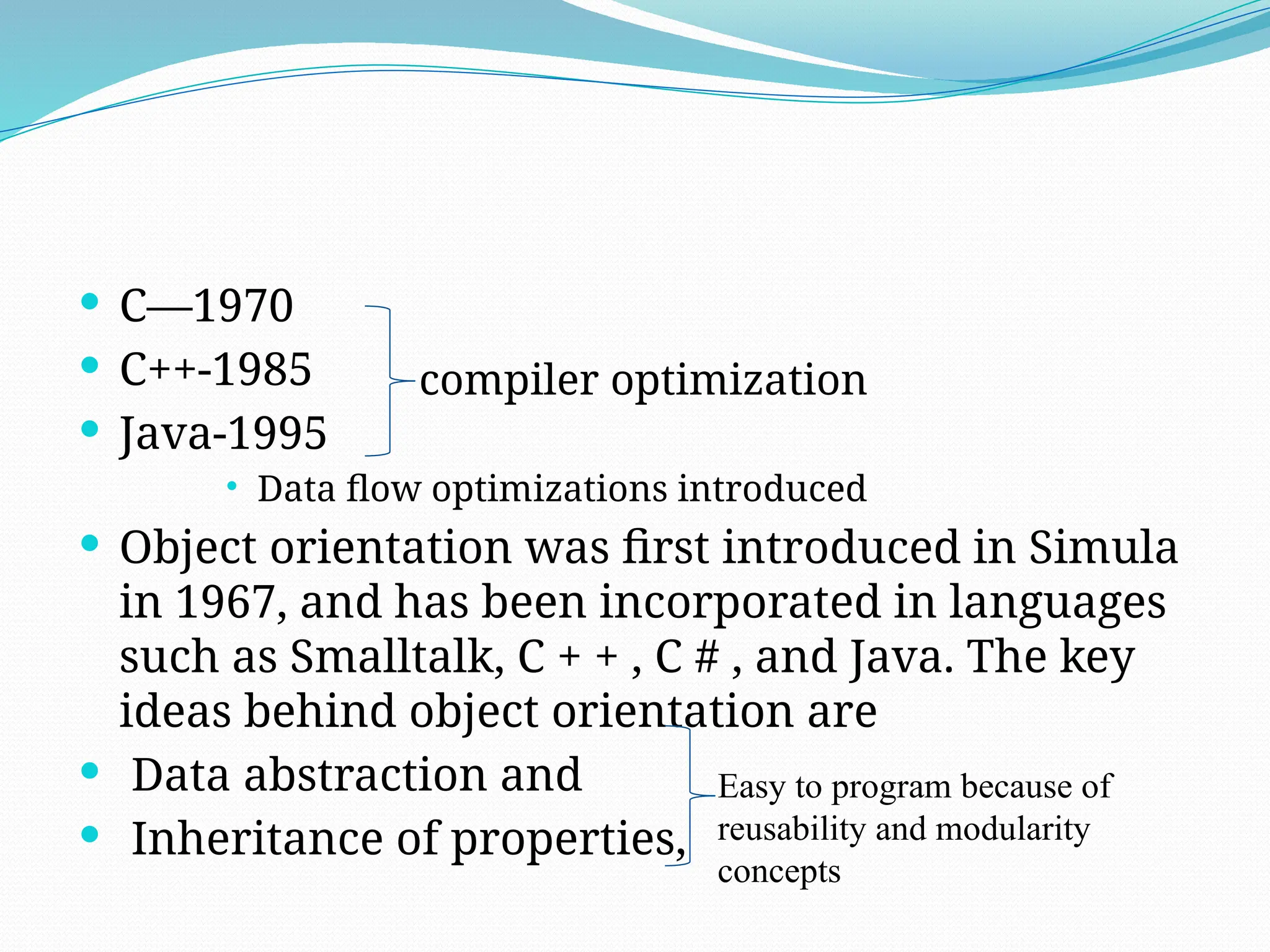

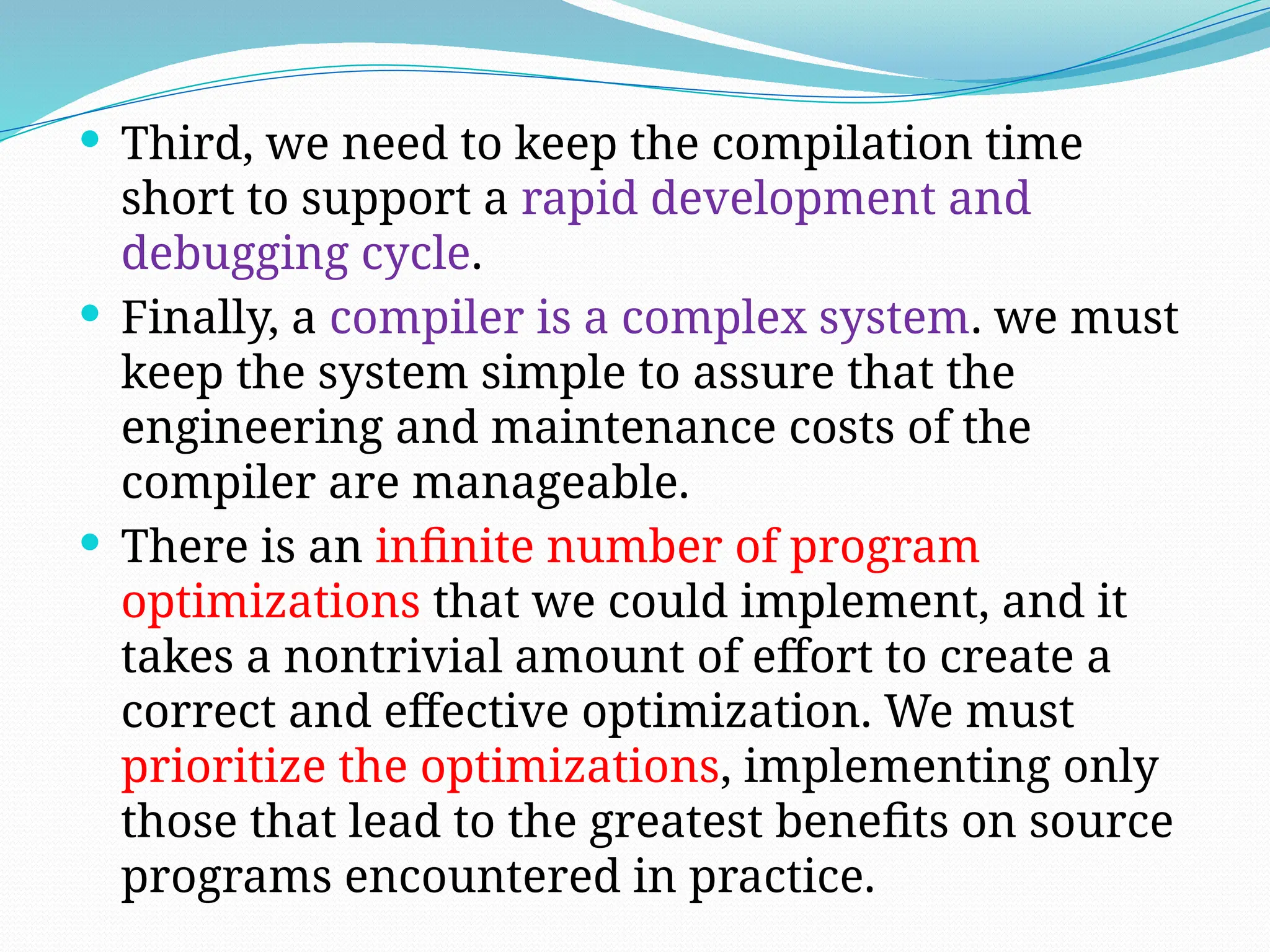

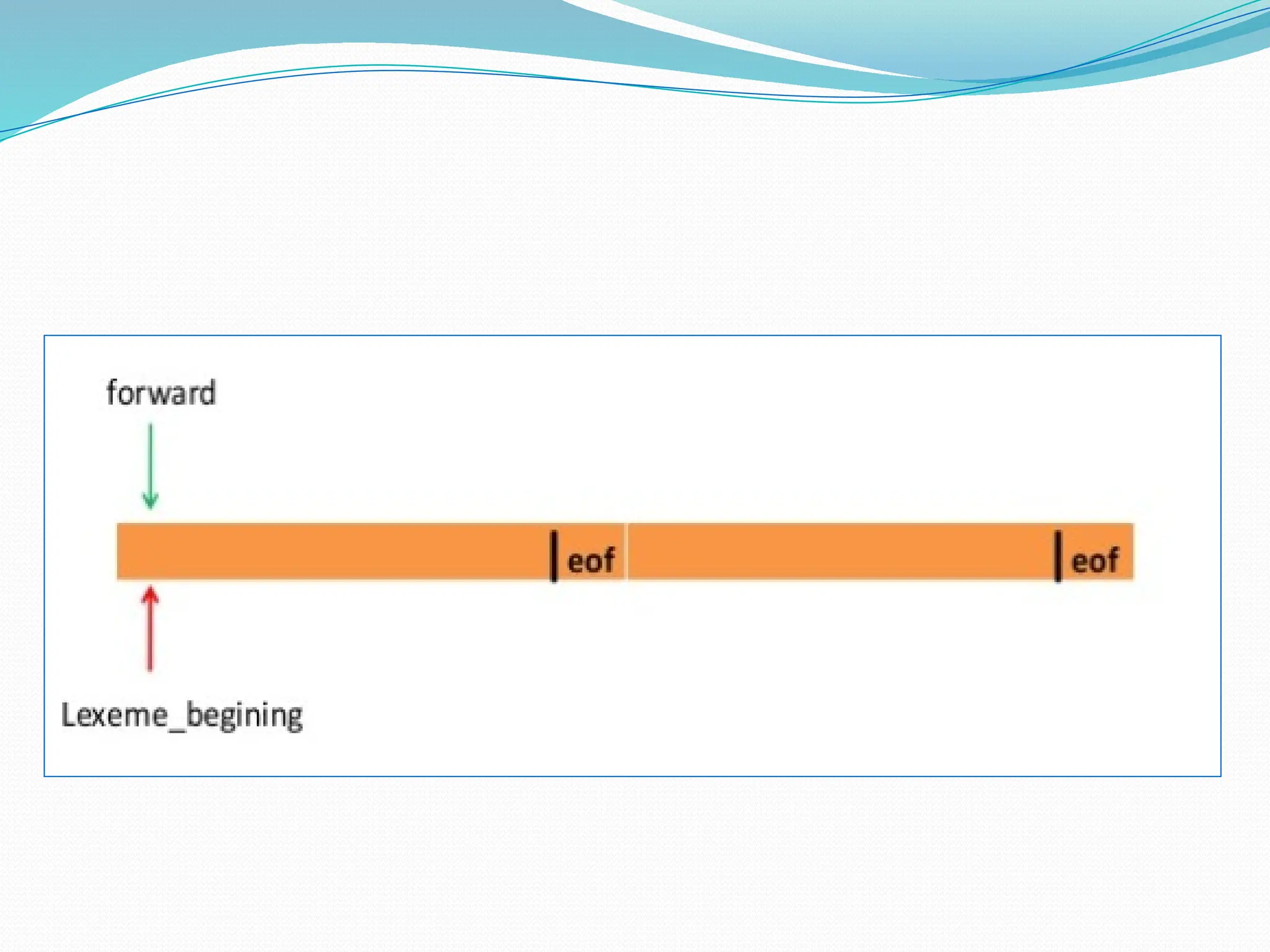

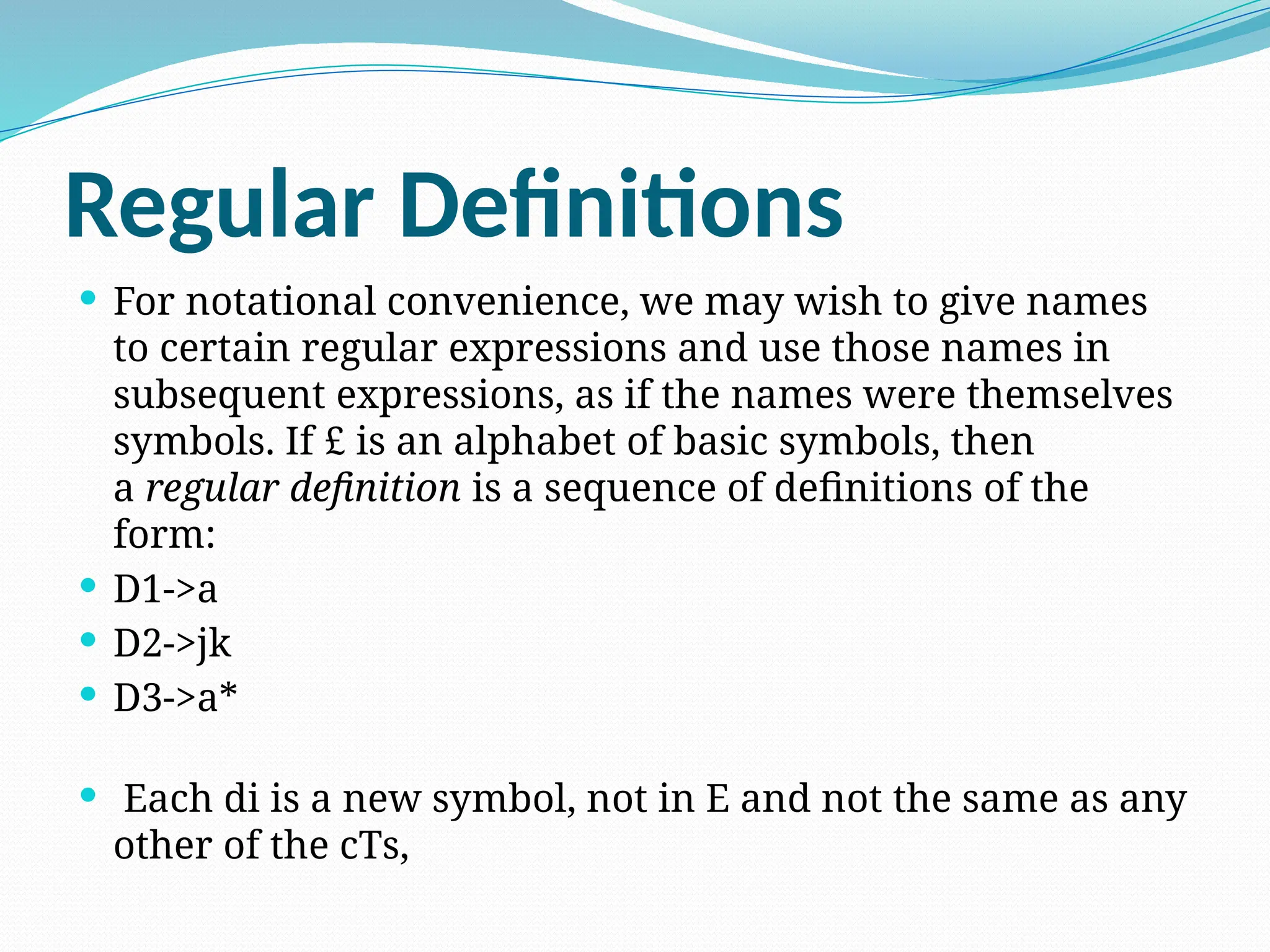

![Write the regular definition for representing

number

Number->[0-9]+

Write the regular definition for representing

floating number

95.89,.987

Digit->[0-9]

Number->digit+

Fnumber->Number.Number

0.987](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptcd-240917100831-401ac4fa/75/ppt_cd-pptx-ppt-on-phases-of-compiler-of-jntuk-syllabus-96-2048.jpg)

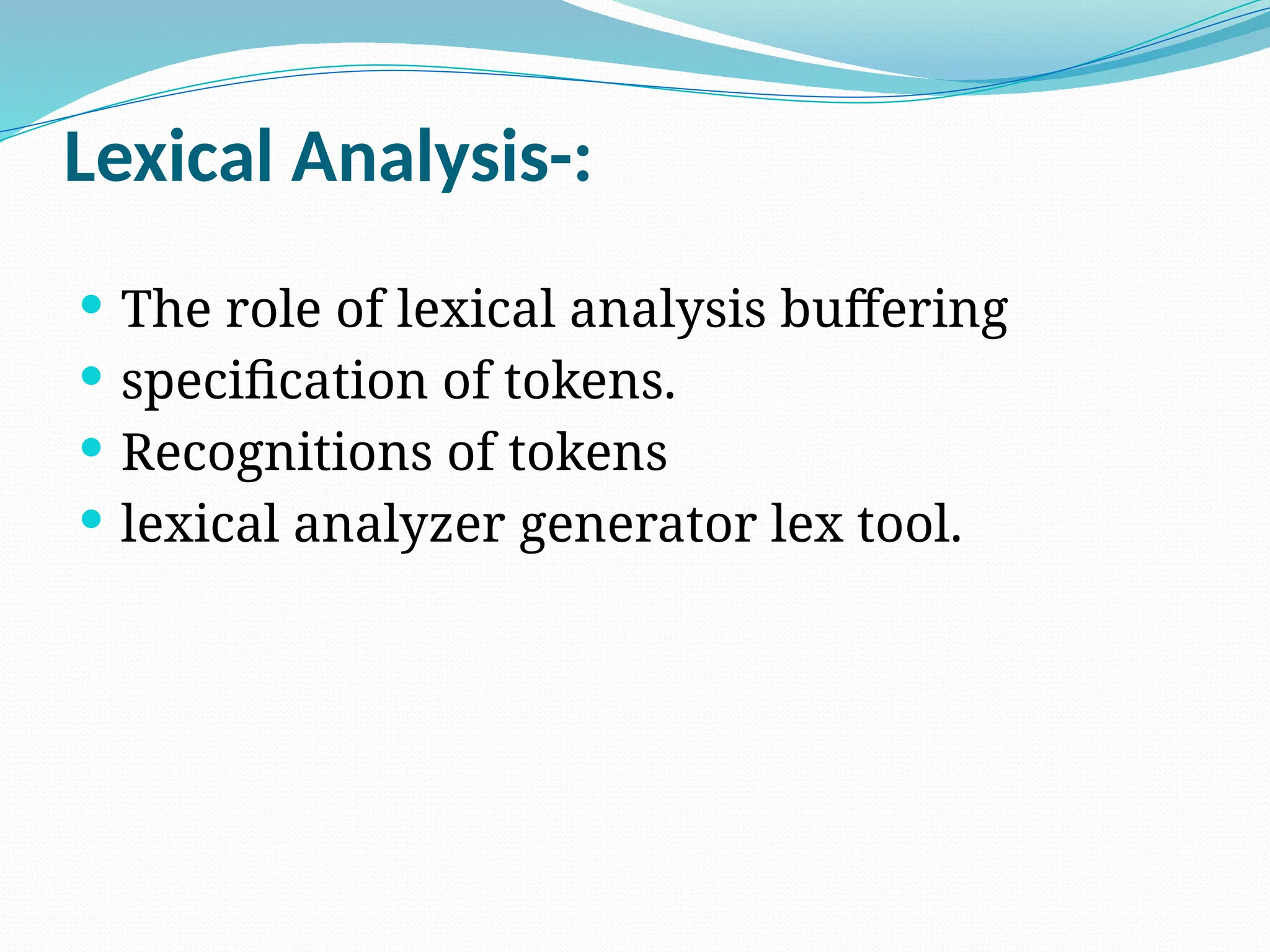

![Rthjj 6878jjnkjk

[A-Za-z0-9]* i++](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptcd-240917100831-401ac4fa/75/ppt_cd-pptx-ppt-on-phases-of-compiler-of-jntuk-syllabus-108-2048.jpg)

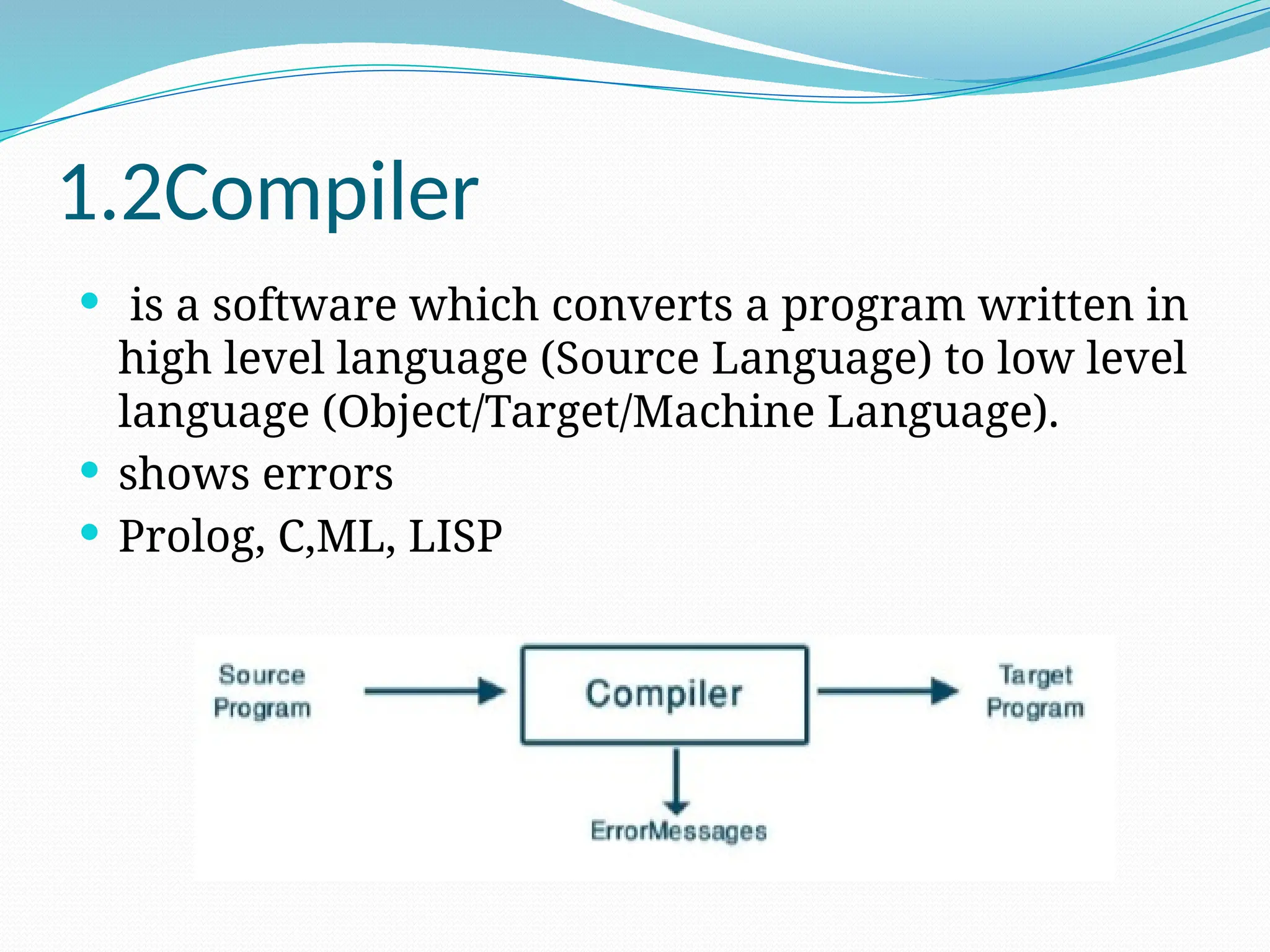

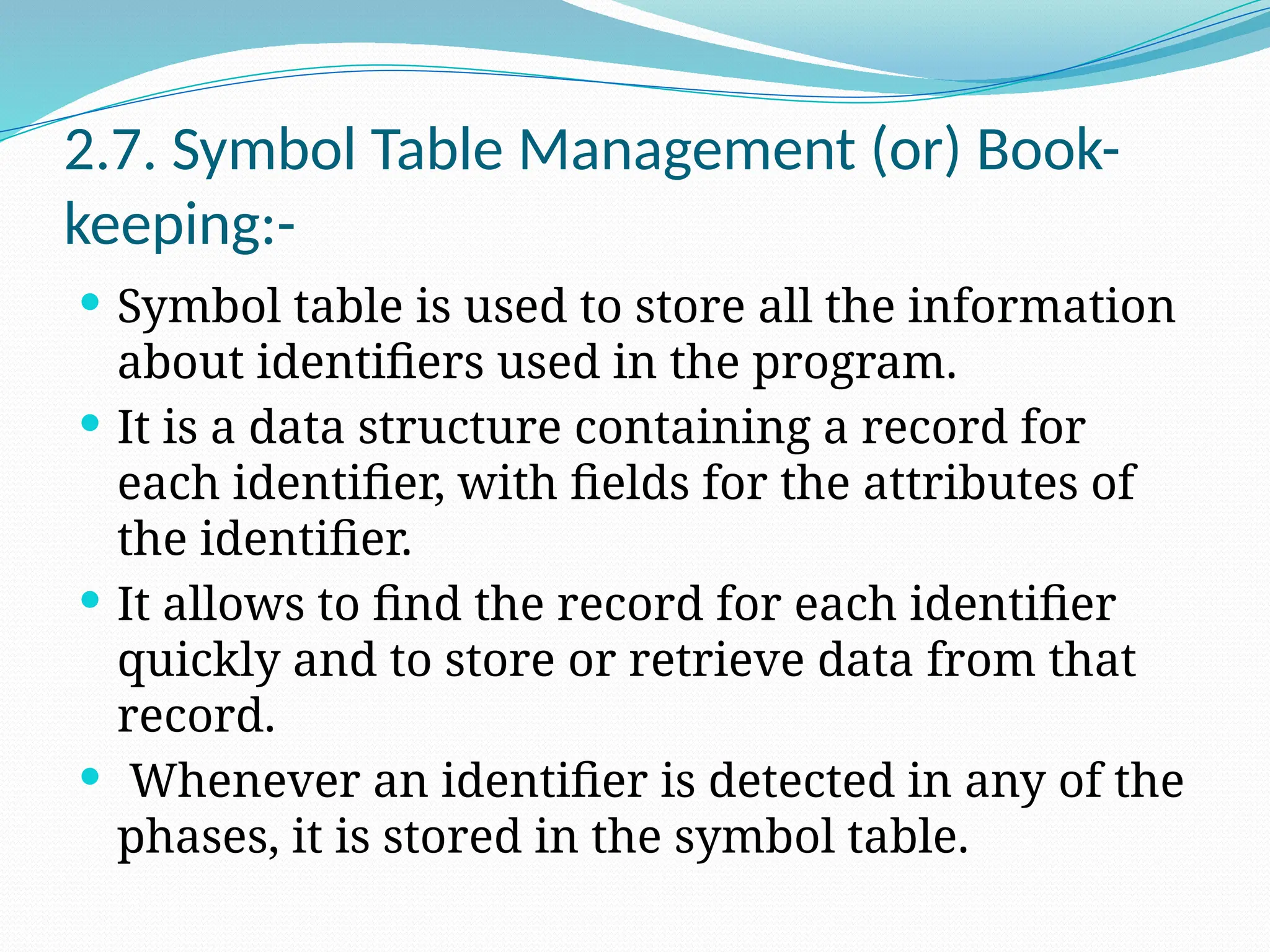

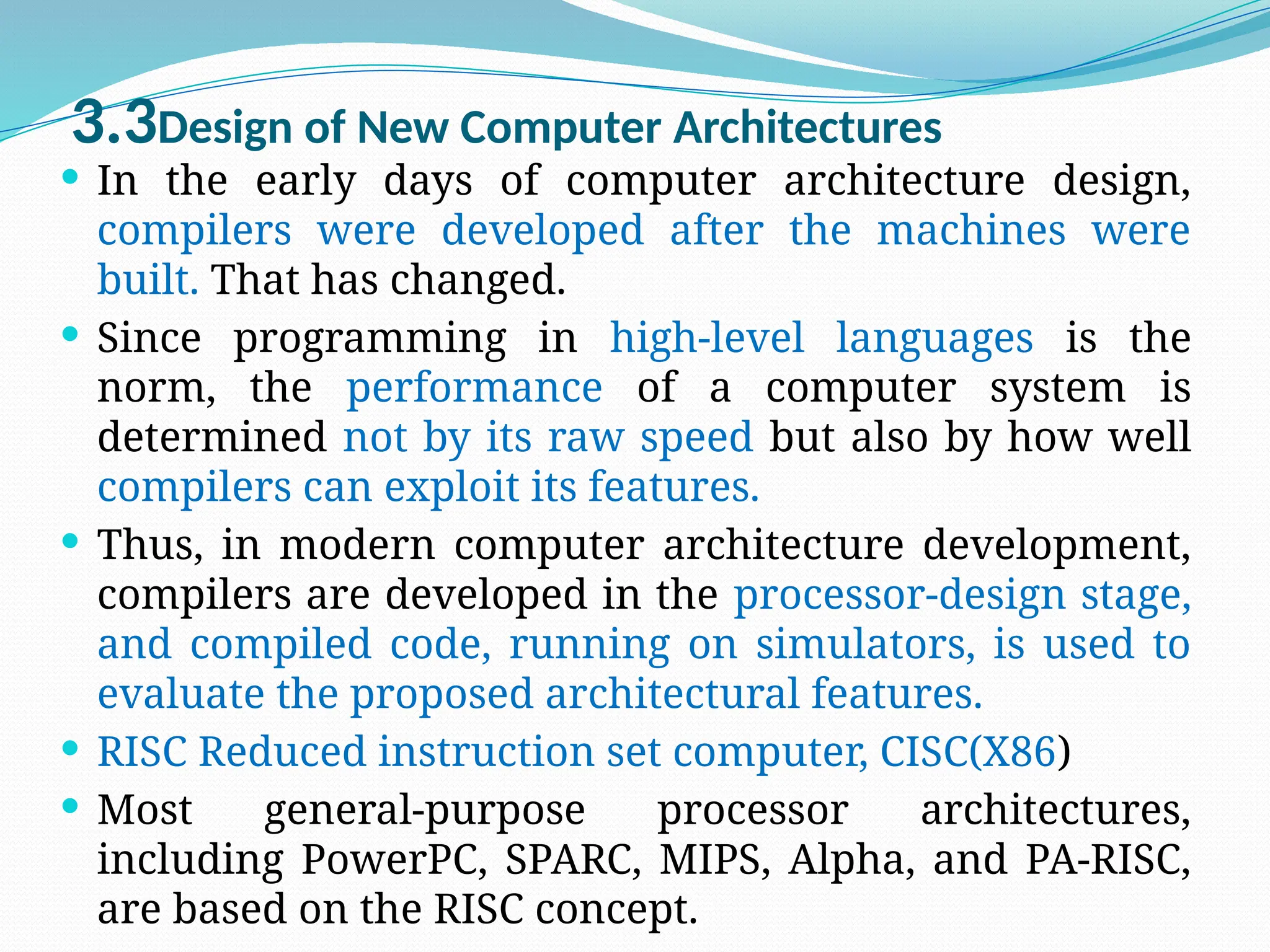

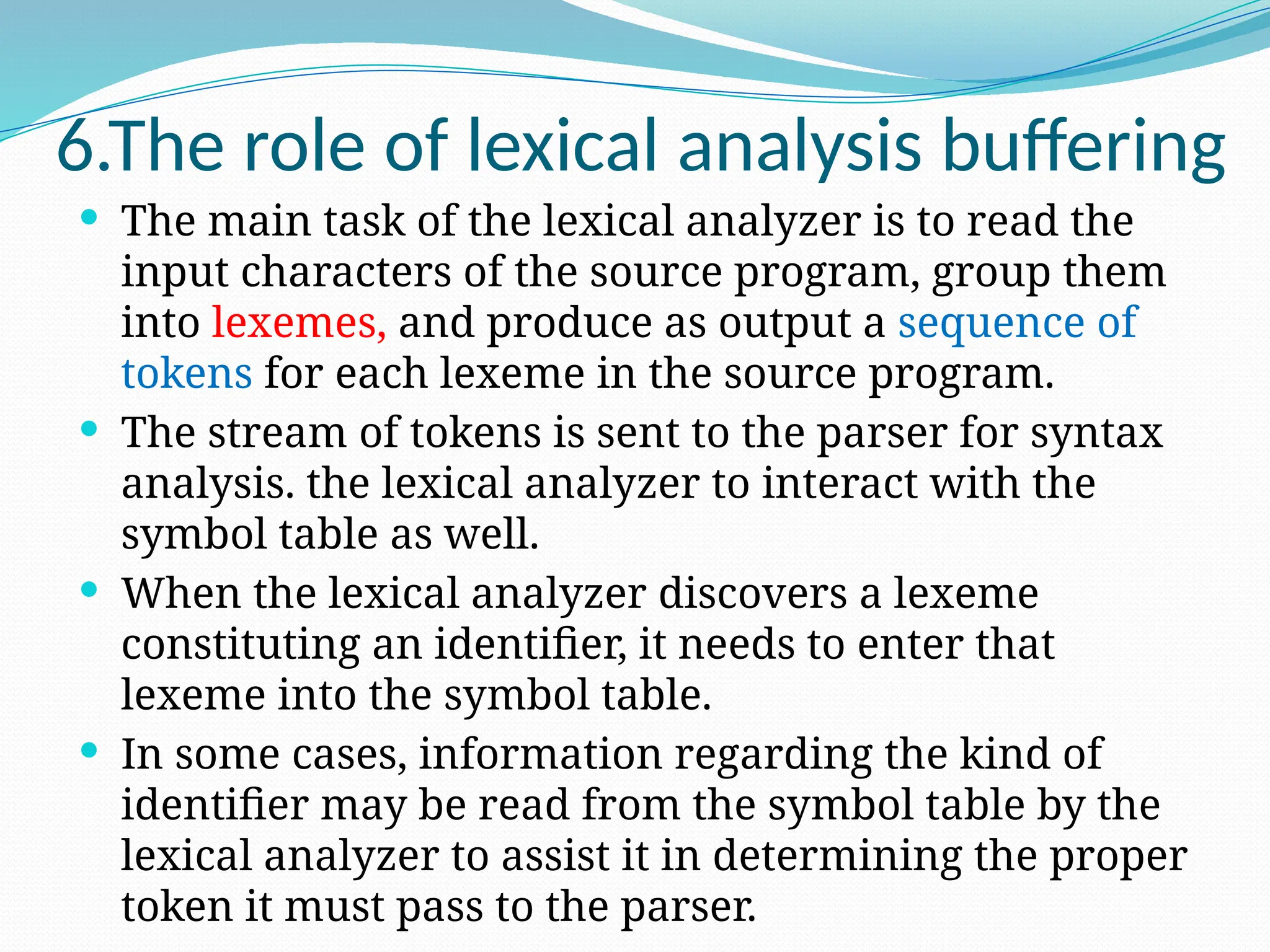

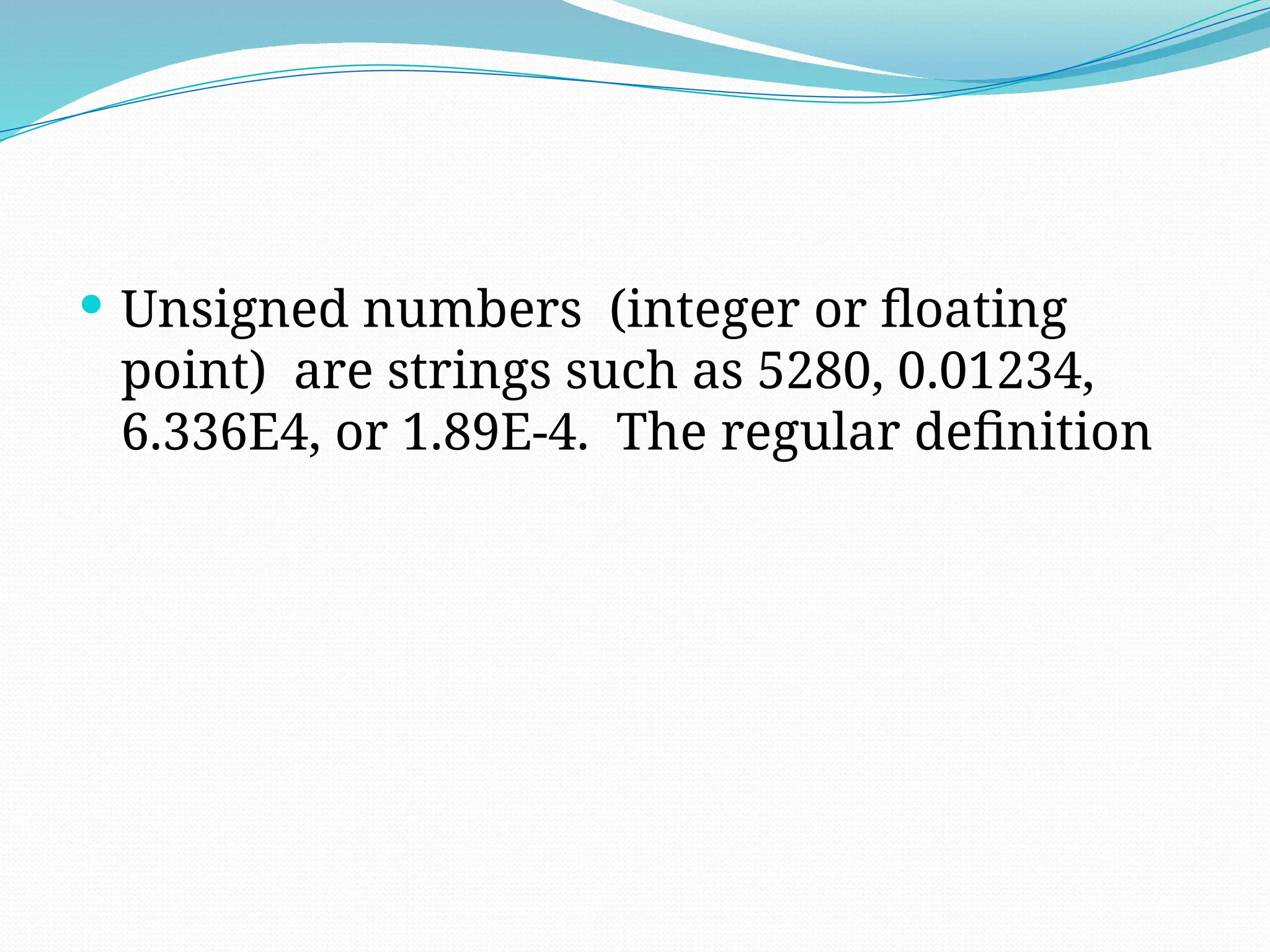

![/*lex program to count number of

words*/

%{

#include<stdio.h>

#include<string.h>

int i = 0;

%}

/* Rules Section*/

%%

([a-zA-Z0-9])* {i++;}

/* Rule for counting number of words*/

"n" {printf("%dn", i); i = 0;}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptcd-240917100831-401ac4fa/75/ppt_cd-pptx-ppt-on-phases-of-compiler-of-jntuk-syllabus-109-2048.jpg)

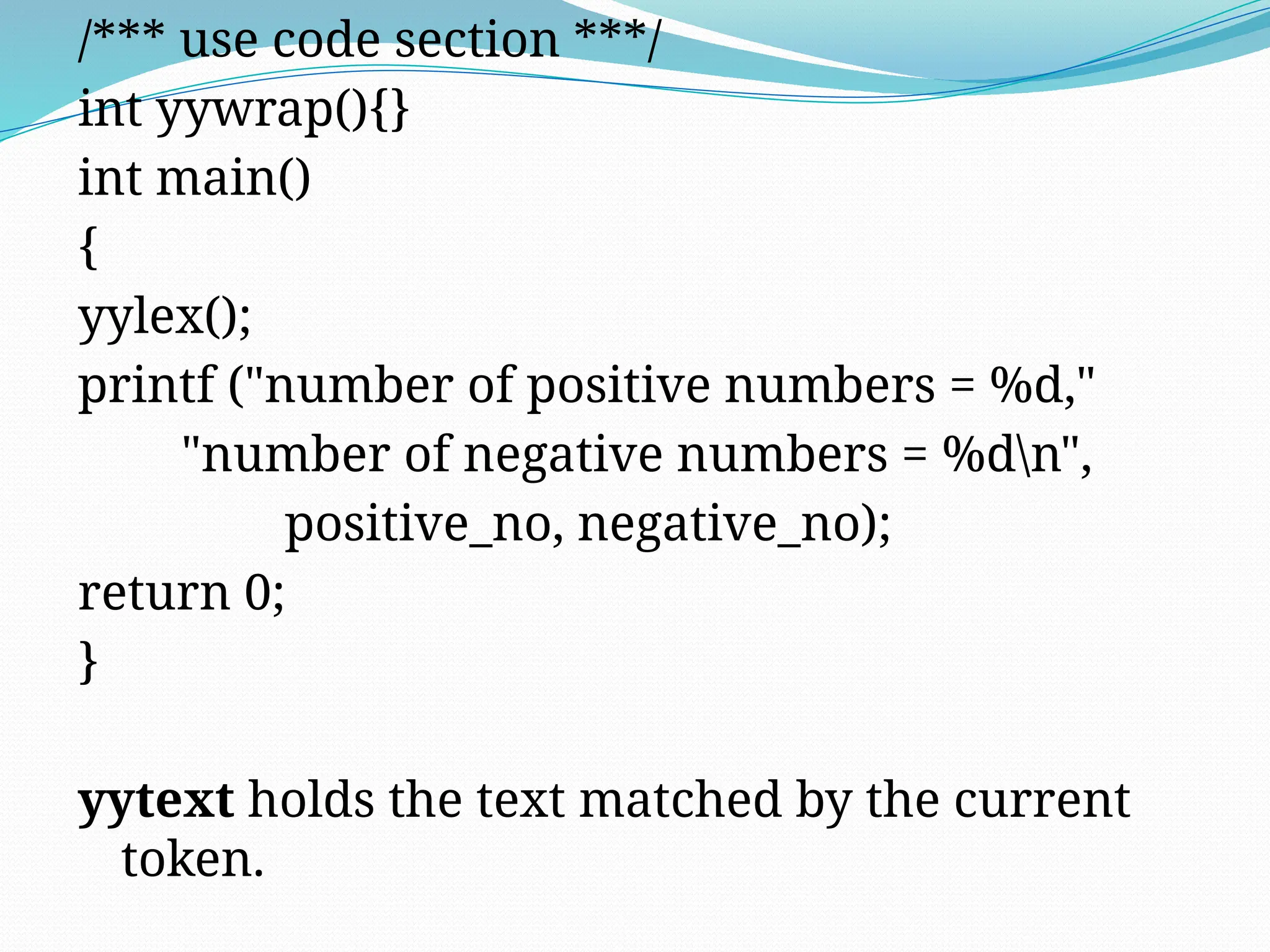

![/* Lex program to Identify and Count Positive and

Negative Numbers */

%{

int positive_no = 0, negative_no = 0;

%}

%

^[-][0-9]+ {negative_no++;

printf("negative number = %sn",

yytext);}

[0-9]+ {positive_no++;

printf("positive number = %sn",

yytext);}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptcd-240917100831-401ac4fa/75/ppt_cd-pptx-ppt-on-phases-of-compiler-of-jntuk-syllabus-112-2048.jpg)

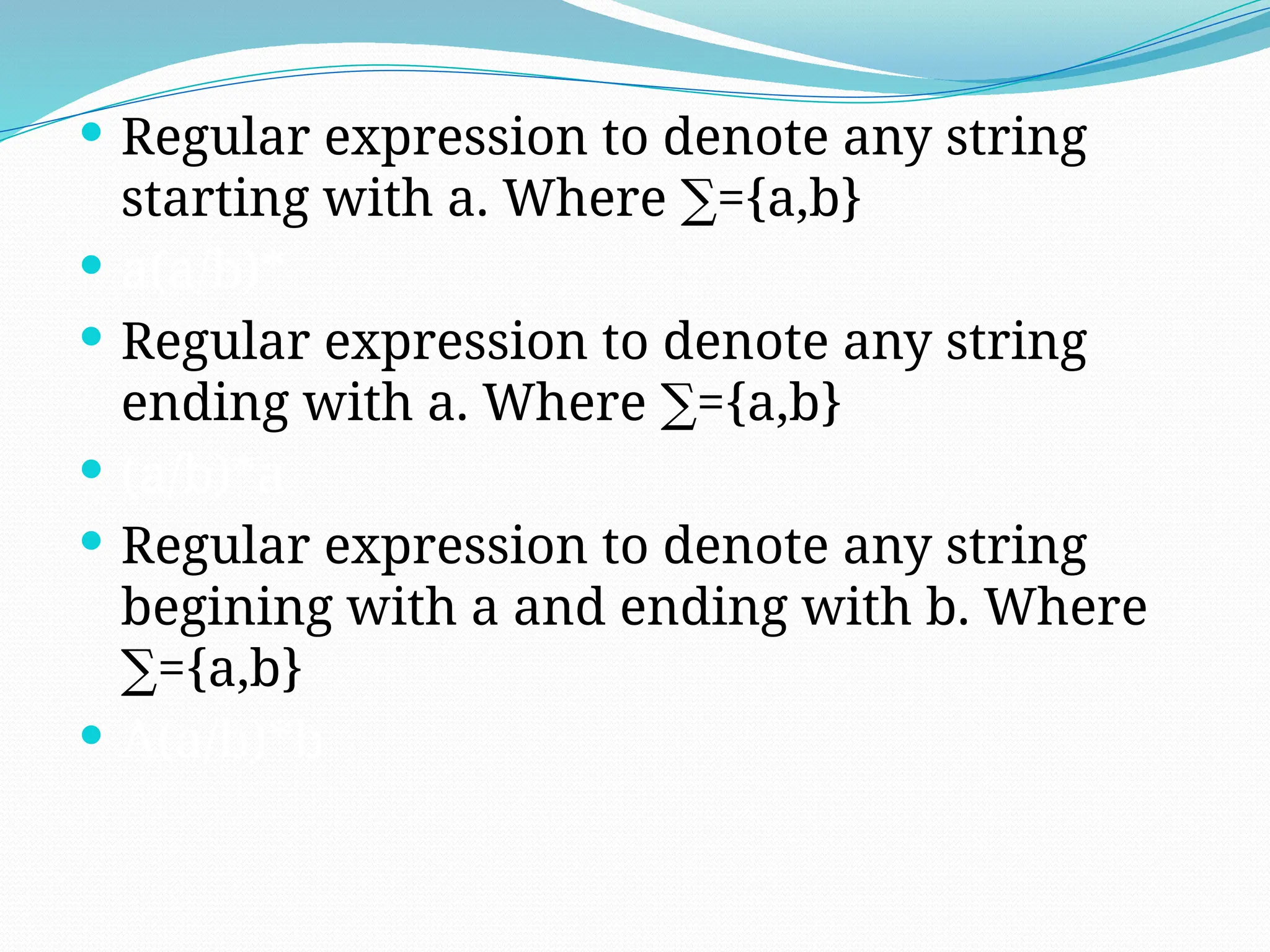

![ All strings of lowercase letters

[a-z]*

All strings of lowercase letters in which

the letters in are in ascending

lexicographic order. String

a*b*c*d*…………z*

All strings of a’s and b’s with an even

number of a’s

(b*ab*ab*)*](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptcd-240917100831-401ac4fa/75/ppt_cd-pptx-ppt-on-phases-of-compiler-of-jntuk-syllabus-116-2048.jpg)

![ All strings of lowercase letters that contain

the five vowels in order.

Letter ->[b-d f-h j-n p-t v-z]

String-> (Letter|a)* (Letter|e)* (Letter|i)* (Letter|o)* (Letter|

u)*

Describe the languages denoted by the following regular

expressions:

(i) (a|b)*a(a|b)(a|b.

(ii) a*ba*ba*ba*](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptcd-240917100831-401ac4fa/75/ppt_cd-pptx-ppt-on-phases-of-compiler-of-jntuk-syllabus-117-2048.jpg)