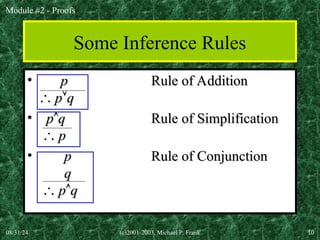

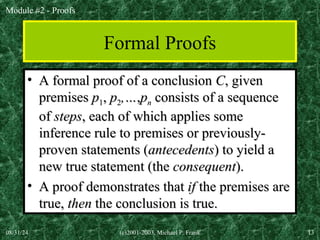

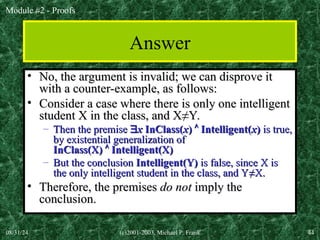

This document provides an overview of mathematical proofs, emphasizing their correctness and completeness as essential for establishing truths in mathematics. It discusses various proof methods, terminology such as theorems, lemmas, and fallacies, and includes examples of formal proofs and inference rules. Additionally, it highlights the significance of proofs in logical argumentation and its applications in fields like program verification and computer security.