Encryption, at its most fundamental level, is the practice of transforming information in such a way that it becomes unintelligible to anyone who does not possess the knowledge or key to reverse the transformation. The very word “encryption” comes from the Greek term kryptos, meaning hidden, and has been part of human civilization for thousands of years. Long before the rise of modern computers and advanced mathematical cryptosystems, ancient societies developed ingenious methods of concealing messages. These early techniques, which we collectively call classical encryption, relied more on clever manipulation of letters and symbols than on complex computation. Yet, despite their apparent simplicity by today’s standards, classical encryption methods played pivotal roles in shaping history, protecting kingdoms, enabling espionage, and influencing wars.

The significance of classical encryption cannot be overstated. From the dusty scrolls of Egypt to the battlefields of World War II, codes and ciphers determined the fates of nations. When Julius Caesar communicated with his generals, he relied on a simple substitution cipher. When the European powers fought during the Renaissance, diplomats and spies devised increasingly sophisticated ways of concealing information. By the twentieth century, entire military campaigns depended on the security of cipher machines like the German Enigma. Each of these examples demonstrates how encryption evolved alongside human civilization, reflecting both our intellectual creativity and our constant struggle between secrecy and discovery.

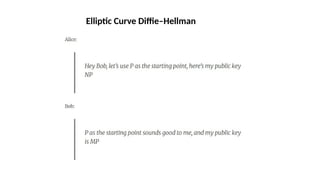

To appreciate the story of classical encryption, one must first understand its foundations. The basic ingredients of any cryptographic system are threefold: the plaintext, which is the original message; the ciphertext, which is the transformed, unreadable output; and the key, which determines how the transformation occurs. In classical ciphers, the operations usually involve substituting letters with other letters or rearranging the order of characters in the message. These two broad families—substitution ciphers and transposition ciphers—formed the backbone of classical cryptography.

One of the earliest known encryption devices was the Spartan scytale, a simple but effective transposition method used around 500 BCE. A strip of parchment was wound around a rod of a certain diameter, and the message was written lengthwise. When unwound, the letters appeared scrambled, and only someone with a rod of the same size could reconstruct the original text. Around the same time, the Hebrew Atbash cipher appeared, a monoalphabetic substitution system where the first letter of the alphabet was replaced with the last, the second with the second-to-last, and so forth. Although elementary, these methods illustrate how ancient peoples conceived of secrecy through systematic alteration of symbols.

The most famous classical cipher is undoubtedly the Caesar cipher, named after Julius Caesar, who emp

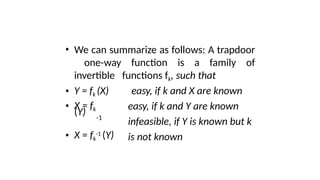

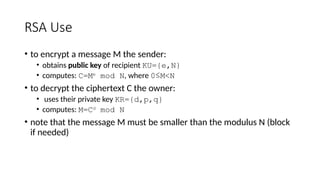

![• It is computationally easy for the receiver

B to decrypt the resulting

ciphertext using the private key to

recover the original message:

M = D(PRb,C) = D[PRb, E(PUb,M)]

• It is computationally infeasible for an

adversary, knowing the public key,

PUb,to determine the private key, PRb.

• It is computationally infeasible for an

adversary, knowing the public key,

PUb, and a ciphertext, C, to

recover the original message, M.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module2-250912082635-6cbc01e5/85/modernencryptionthatinvolvesdes-ppt-pptx-18-320.jpg)

![• The two keys can be applied in

either order:

M = D[PUb, E(PRb, M)] = D[PRb, E(PUb, M)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module2-250912082635-6cbc01e5/85/modernencryptionthatinvolvesdes-ppt-pptx-19-320.jpg)