This document provides an overview and table of contents for the book "Municipal Finances: A Handbook for Local Governments". The handbook contains 8 chapters that cover topics related to municipal finances, including intergovernmental finances, metropolitan governance and finance, municipal financial management, managing local revenues and expenditures, managing local assets, managing external resources, and achieving transparency and accountability. It is intended to serve as a reference for local governments on best practices in municipal financial management. The table of contents provides a high-level summary of the topics and issues covered within each chapter.

![validity. Conducting a sensitivity analysis

assesses reliability. The key parameters used to

create the estimates are varied, and if this leads

to large changes in the results, the projection is

assumed to have a low degree of reliability.

6. Monitor and compare revenue collection with

the estimates. Monitoring serves both to assess

the accuracy of the projections and to deter-mine

whether there is likely to be any budget

shortfall or surplus.

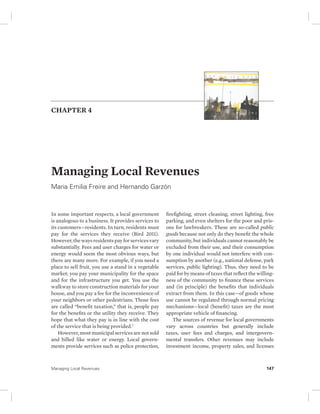

Box 4.24 Methods for Calculating Growth Rates and Projecting Revenues

Years Forward

Percent Change: The first option compares

consecutive time periods using the following

formula:

Percent change = [(CR – PR)/PR]*100, (Eq.1)

where CR = Current Revenue and PR = Past

Revenue.

Average Growth Rate: For a longer period,

the same change formula can be used, but the

total percent would be divided by the number

of years (N):

Average growth rate = {[(CR−PR)/PR] /N}*100

(Eq. 2); for (tn−to).

However, for such longer periods, the

use of the first and last year may be suit-able

only when the revenue changes are

rather uniform. A more accurate growth rate

would be obtained using compound growth

rates.

Compound Annual Growth Rate

(CAGR): CAGR takes into account the first and

the last value of the particular time period but

includes the effect of the annual compound-ing

periods in the final growth rate. The results

are fairly reliable if the changes from one year

to the next are rather smooth. The CAGR can

be computed as CAGR (tn−to) = ([(Vtn/Vto)*1/

(tn−to)] – 1)*100 (Eq. 3), Vto = initial value,

Vtn = last value, and 1/(tn−to) = number of

years or using the basic formula of

VTn = VTo (1 + r)n−1

and solving for r:

r = {exp[ln(VTn /VTo)/N]−1}*100.

Arithmetic Mean Growth Rate:

Alternatively, if the time series is character-ized

by volatility in yearly revenues, the first

and the last year might not be representative;

in such cases, it may be better to use the arith-metic

mean growth rate (also known as the

Arithmetic Mean Return—AMR). The formula

of the AMR is as follows:

AMR = 1/n(X1 + … + Xn), (Eq. 4)

where n = number of time periods of one

year, and Xi = percent revenue change for

period i.; computed as [(CR – PR)/PR]*100

(Eq. 1) i = 1…to… n.

Linear Trend Growth Rate: Another option

is to compute the CAGR of the trend line,

calculated by the least squares method. This

would provide the growth rate of the trend

in revenues for the particular time period. For

example, Excel automatically draws the trend

line, calculates the trend equation, and R2,

which indicates the quality of the forecasting

trend.

198 Municipal Finances](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/28b91a67-02cd-4f0b-9dd0-98c709df8d25-141215172912-conversion-gate02/85/MF-Handbook-230-320.jpg)

![• Managing capital expenditures requires

long-term planning of both capital investment

projects and financing; transparent and com-petitive

procurement; and strong capacities

for contract management.

• A medium-term expenditure framework is

a robust instrument for supporting effective

expenditure management and for perfor-mance

monitoring. It should be combined

with disciplined audits and financial and

regulatory oversight.

• Expenditure management is not merely a

technical process but also a very political

one. Thus, effective expenditure management

requires good understanding and manage-ment

of the political economy implications of

the plans and decisions.

Notes

1. This section was prepared based on World

Bank 1998, chapter 2.

2. More details are available at http://ec.europa

.eu/europeaid/what/economic-support

/ public-finance/documents/ethiopia

__ addisababa_pefa_report_2010_en.pdf.

3. The entire assessment can be found at

http://ec.europa.eu/ europeaid/what

/economic-support/ public-finance

/ documents/ ethiopia_ _addisababa_pefa

_report_2010_en.pdf.

References

Adrianov, Valentin, Sergei Sivaev, Raymond

Struyk, and Emin Askerov. 2003. Russia’s

Winter Woes: Tariff Setting for Local Utilities

in a Transition Economy. Moscow: Institute for

Urban Economics.

Chavez, Carlos. 2002. “Public-Private Partnership

and Tariff Setting: The Case of Chile.” Paper

for the OECD Global Forum on Sustainable

Development, Paris, April.

Chernyavsky, Andrei, and Karen Vartapetov.

2004. “Municipal Finance Reform and Local

Self Governance in Russia.” Post-communist

Economies 16 (3), September.

DANCED (Danish Co-operation for

Environment and Development). 2002.

“Solid Waste Tariff Setting—Guidelines

for Local Authorities.” Proposal for the

Department of Environmental Affairs and

Tourism, Tanzania, April.

Ebel, R., and F. Vaillancourt. 2007.

“Intergovernmental Assignment of

Expenditure Responsibility.” In The

Kosovo Decentralization Briefing Book.

Prishtina: Kosovo Foundation for an

Open Society.

Helgason, Sigurdur. 1997. International

Benchmarking Experiences from

OECD Countries. Paper presented in

Paris, February.

Kopanyi, M., S. El Daher, and D. Wetzel, eds.

2004. Intergovernmental Finances in Hungary,

A Decade of Experience. Washington, DC:

World Bank Institute.

Shugart, Chris, and Ian Alexander. 2009.

“Tariff Setting Guidelines.” Public-Private

Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF),

Working Paper No. 8, World Bank,

Washington, DC.

Tausz, Katalin. 2004. “Managing Household

Arrears in Utility Services—Social

Policy Challenges and Responses.” In

Intergovernmental Finances in Hungary,

A Decade of Experience, edited by M. Kopanyi,

S. El Daher, and D. Wetzel. Washington, DC:

World Bank Institute.

TERI (The Energy and Resource Institute

[India]). 2010. Review of Current Practices

in Determining User Charges and Incorporation

of Economic Principles of Pricing of Urban

Water Supply. New Delhi, India. New Delhi:

TERI.

USAID (U.S. Agency for International

Development). 2006. Managing Municipal

Managing Local Expenditures 273](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/28b91a67-02cd-4f0b-9dd0-98c709df8d25-141215172912-conversion-gate02/85/MF-Handbook-305-320.jpg)