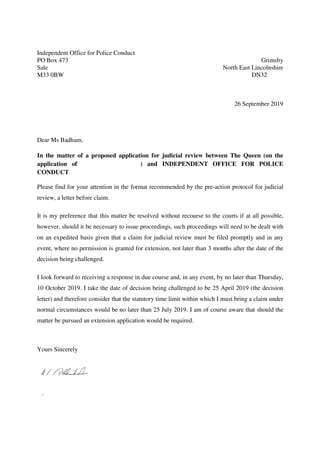

Letter before action 26 sept 2019 r

- 1. Independent Office for Police Conduct PO Box 473 Sale M33 0BW Grimsby North East Lincolnshire DN32 26 September 2019 Dear Ms Badham, In the matter of a proposed application for judicial review between The Queen (on the application of ) and INDEPENDENT OFFICE FOR POLICE CONDUCT Please find for your attention in the format recommended by the pre-action protocol for judicial review, a letter before claim. It is my preference that this matter be resolved without recourse to the courts if at all possible, however, should it be necessary to issue proceedings, such proceedings will need to be dealt with on an expedited basis given that a claim for judicial review must be filed promptly and in any event, where no permission is granted for extension, not later than 3 months after the date of the decision being challenged. I look forward to receiving a response in due course and, in any event, by no later than Thursday, 10 October 2019. I take the date of decision being challenged to be 25 April 2019 (the decision letter) and therefore consider that the statutory time limit within which I must bring a claim under normal circumstances would be no later than 25 July 2019. I am of course aware that should the matter be pursued an extension application would be required. Yours Sincerely .

- 2. 1 IN THE MATTER OF A PROPOSED APPLICATION FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE COURT BETWEEN: THE QUEEN (on the application of ) Proposed Claimant -and- INDEPENDENT OFFICE FOR POLICE CONDUCT Proposed Defendant JUDICIAL REVIEW PRE-ACTION PROTOCOL LETTER BEFORE CLAIM Information required in a letter before claim I. Proposed claim for judicial review To The Independent Office for Police Conduct, PO Box 473, Sale, M33 0BW II. The Claimant of , Grimsby, North East Lincolnshire, DN32 .

- 3. 2 III. Defendant’s reference details Present appeal ref: 2019/115969 (linked appeal ref: 2017/082079) IV. Details of the legal advisers, if any, dealing with this claim None. V. Details of the matter being challenged The decision of the Independent Office for Police Conduct (the ‘Proposed Defendant’) not to review the findings of an investigation carried out by Humberside Police or direct that the complaint be re-investigated. VI. Details of any interested parties None proposed. However, it is envisaged that a potentially significant number of people would benefit from the issue being reviewed. Namely, those who would in similar circumstances to the Proposed Claimant be affected by the Proposed Defendant’s powers being exercised to their detriment. VII. The issue Background 1. The proposed claimant (‘PA’) was a victim of a miscarriage of justice which he believes was the result of a malicious prosecution – the consequence of a stitch-up between Humberside police, Grimsby Magistrates court and the Crown Prosecution Service. Despite all the safeguards built into each stage of the criminal justice system, he was investigated, prosecuted and found guilty of an offence he did not commit. 2. On 27 August 2015 PA was involved in an incident which led to him being arrested and charged with an offence under s.5 of the Public Order Act 1986. Two members of the public provided witness statements for the purposes of the criminal proceedings. PA believes that the arresting officer had incited at least one of the witnesses to make a false statement and that both witnesses had made false statements therefore committing perjury before the court.

- 4. 3 3. A hearing in relation to the offence took place on 30 September 2015 at which PA pleaded not guilty (he had formally confirmed earlier on 4 September that a ‘not guilty’ plea would be entered at the first hearing). The court directed that PA was prohibited from cross-examining the witness in person and arrangements made for a solicitor to do so at a further hearing listed for 15 December 2015. PA submitted a complaint to Humberside Police on 8 November 2015 regarding the arresting officer, alleging he had incited the witnesses to give false accounts and explicitly reported perjury in respect of their statements (he asked to be provided crime numbers). 4. The complaint was formally recorded on 24 November 2015 and a copy of the record enclosed in a letter of 1 December 2015 which explained that it is practice to suspend investigation of the complaint until after the proceedings1 . Only the allegations against the police were recorded (those against the witnesses were not) which prompted PA to write to the force on 2 December and request that it also investigate his allegations that the two members of the public had made false statements before the court. In its response of 3 December the force stated that the court was the correct forum to challenge the matter and that it was not practice to investigate such allegations unless the magistrates or judge recommended that the police do so2 , unless there were aggravating circumstances3 and it would be considered an abuse of the complaints process if it investigated the allegation under the Police complaints process as the situation stood4 . 5. PA subsequently forwarded his complaint about the arresting officer to the Court on 11 December 2015, together with an account stating that two members of the public had both made untrue witness statements. The case went ahead in his absence during which he was found guilty and convicted of an offence under s.5 of the Public Order Act 1986 and sentenced on 22 December 2015. He did not attend the 15 December 2015 hearing, after discovering which judge would be trying the case. He expressed without reservation in his 11 December correspondence that he did not consider the judge, ‘a fit and proper person to hear 1 An investigation may be suspended under Regulation 22 of the Police (Complaints and Misconduct) Regulations 2012 which would, if it were to continue, prejudice any criminal investigation or proceedings 2 This is contrary to the view of the CPS whose advice is that ‘where a judge or magistrate believes that some evidence adduced at trial is perjured s/he can recommend that there should be a police investigation. The absence of such recommendation does not mean that there is no justification for an investigation’. 3 Witness statements were false and other evidence was clearly unreliable, inconsistent and/or of questionable credibility, so there were aggravating circumstance. 4 It was in fact the police who were abusing the complaints process by suspending the investigation of the police conduct complaint for several reasons; one of which being that the alleged offence committed by the police was more serious than the offence that the defendant was charged with.

- 5. 4 the case’. This was on the basis that the judge presiding over the matter was the same judge who had presided over a recent earlier case involving Council tax liability who had unequivocally accepted a statement knowing it to be false5 . PA had as a consequence been defrauded with an attached claim of costs (evidence of this had also been sent to the Court on 11 December). The judge sentencing on 22 December 2015 was clearly oblivious to the proceedings as he responded to PA’s protest at being wrongly convicted that he had a chance to put his side of the story at the trial but did no turn up (his side of the story was documented in mitigating evidence which the court just did not bother to take into account). 6. The police wrote on 29 December 2015 to inform PA that the conduct complaint, which had been unlawfully suspended, would resume as the court case against him had concluded. The complaint was forwarded to Inspector Parsons to be dealt with by way of “Local Resolution” (the statutory conditions were not met for the complaint to be handled that way). A complaint may not lawfully be subjected to local resolution if the conduct complained about is sufficiently serious to warrant criminal or disciplinary proceedings to be brought against the person whose conduct is complained of (the complaint required fully investigating). This decision is based on the wording of the complaint alone so the merit of the complaint or the possible outcomes is irrelevant. The criteria for whether a complaint can be dealt with by Local Resolution are set out in paragraph 6 (sub-paragraphs 6 to 8) of Schedule 3 of the Police Reform Act 2002 Act, so despite the letter stating that the complaint was being dealt with in accordance with this legislation it in fact was not. 7. The complaint concerned PA’s suspicion that the arresting officer had incited a witness to commit perjury and had made a wrongful/unlawful arrest, leading to false imprisonment. The force could not conceivably have been satisfied that if proven the conduct complained of would not have justified the bringing of criminal and/or disciplinary proceedings against the arresting officer. But despite the force obviously handling the matter unlawfully there is no immediate avenue to redress such a statutory breach within the Police Reform Act. The Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) has no remit to intervene because the force is entrusted to determine the Relevant Appeal Body (the RAB test) who will, depending on the severity of the misconduct, be either the IOPC or the police force. In the present case the 5 An officer gave evidence in court which he knew to be false in Council Tax liability proceedings brought by North East Lincolnshire Council. Indisputable evidence is held to support why the statement was untrue and why the Claimant could not have believed it to have been true. It was clear from submissions in the proceedings that the Council deliberately intended to deceive the court yet the “District Judge” nevertheless turned a blind eye.

- 6. 5 police force was the Relevant Appeal Body, but only because the test was unlawfully carried out and determined to be a complaint suitable to be subjected to Local Resolution. It is only once the Local Resolution process has concluded that the opportunity arises for the lawfulness to be challenged of the process by which the force determined the method of investigation. Consequently, all the IOPC can do when the question of a breach of procedure is raised with it is to pass the information to the force because the IOPC is not the Relevant Appeal Body. It is almost certain therefore that the complaint was wrongly considered suitable for Local Resolution deliberately in order to delay and obfuscate the procedure. Mishandling the complaint bought Humberside police over 500 days which is how long it took the force to complete the Local Resolution process. The force’s 29 December letter went on to advise PA to contact the Professional Standards Department (PSD) if he was considering making an appeal in relation to his conviction or sentence. 8. PA replied on 5 January 2016 explaining he had not made a decision on whether to make an appeal but exploring the possibilities of doing so. He clarified that if he did appeal he nevertheless expected the matter to be investigated whether or not he was successful. He reiterated his concern about the two false witness statements made by members of the public (he wanted clarification concerning those crimes he had reported). He made further enquiries with the court which were responded to on 13 January. It was confirmed that he was able to appeal against his conviction and sentence (Crown Court) even though the Trial took place in his absence. He would need to include the reason why he was asking for permission to appeal outside the 21 day limit in his notice of appeal. He was told that it was on the basis that he made a conscious decision not to attend for his Trial in the Magistrates Court, for reasons he had expressed in his e-mails that the Legal Team Manager considered it was not appropriate to re-open the case under s.142 of the Magistrates Court Act 1980. 9. PA wrote to the Police on 1 February 2016 and confirmed that the Magistrates’ court had refused to reopen the case6 and he was receiving no co-operation from the court regarding its decision7 and therefore had “for the foreseeable future decided against appealing”. He asked 6 Section 142 of the Magistrates' court Act 1980 makes provision for reopening a case ‘if it appears to the court to be in the interests of justice to do so’ including for the case to ‘be heard again by different justices’. Section 11 provides that: ‘the court shall not proceed in the absence of the accused if it considers that there is an acceptable reason for his failure to appear’. 7 A police letter stating that it did not investigate allegations of perjury unless requested to by the court was forwarded to the court, along with evidence proving beyond all doubt that the Council’s evidence was perjured and asked that it confirm this to the police. The court’s response was that it would not be taking any action regarding the allegations of perjury.

- 7. 6 for an update on the police force’s investigation into his complaint regarding the arresting officer, and otherwise sought confirmation that the allegations of the two false witness statements had been recorded as crimes. He had also written to the Magistrates’ court on 13 February with further representations to justify why his case should have been reopened. His correspondence was copied to the PSD and had alleged collusion between the police, CPS and Courts which was backed up with evidence. For example, (i) the case proceeded where the evidence fell far below the minimum standards expected for a fair trial (in fact there was no evidence), (ii) PA had been insufficiently informed about the proceedings and was therefore completely in the dark regarding his rights, (iii) he had remained entirely voluntarily to help police with their enquiries so the arrest was unnecessary and unlawful, (iv) it was confirmed that a total of 7 CCTV cameras covered relevant areas but no request had been made for the video footage to be retained on the relevant day and had consequently been overwritten therefore video evidence had been concealed etc. etc. 10. The court’s Legal Team Manager replied on 15 February 2016 refusing again to reopen the case. His justification was that PA deliberately chose not to attend the Trial on the 15 December 2015 and it was on that basis the case proceeded in his absence (he was unable to challenge the evidence of the prosecution witnesses so the Judge found him guilty). He was advised once more that if he wished to appeal the decision he should ask the Crown Court to consider allowing him to appeal outside the time limit and if it allowed him to do so then he could challenge the evidence of the prosecution witnesses. 11. The Manager was apparently unaware that a court may only convict if it is sure that the defendant is guilty. Even if the judge had not bothered taking into account the various documents PA had submitted to the court, there was enough conflicting material in the trial bundle itself for the credibility of the evidence to have been in question and to have raised doubt as to PA’s guilt. For example the witness statements were inconsistent with one another and conflicted with what was said before they were produced. It was also clear from material in the trial bundle that there were disclosure failings. These far exceeded what were first apparent to PA and became evident once he began researching the laws (to challenge his conviction) which were improperly applied at the time he was prosecuted. PA was not prepared to stand before the same judge who he had not long since complained about to the Judicial Conduct Investigations Office and reported the matter of complaint as a crime to the police and declared unreservedly to the court shortly before the trial that he did not consider

- 8. 7 the Judge, ‘a fit and proper person to hear the case’. Evidently the court could not have considered these to be acceptable reasons for his failure to appear. 12. PA replied stressing the seriousness of his allegations and reiterated that he was alleging that the police, CPS and Courts were complicit in allowing fabricated evidence to convict him for charges of which he was innocent in order to defraud him of a sum of £620 and that the court had no evidence whatsoever with which to find a guilty verdict. 13. The Police had not clarified any of the points which were raised by PA on 1 February 2016 so he chased the PSD for an update on 9 February. Having still no reply he asked on 15 February whether Humberside police had any arrangements in place to restrict his contact, for example, by telephone, email, letter etc., or a combination of these. He was responded to on 16 February and informed by the PSD caseworker that as far as he was aware there was no such policy in place. It was clear from the reply that the PSD has no effective control over the process once the file has been allocated to the Investigating Officer which must amount to a dereliction of duty by the person responsible for the department. He expressed that he could do no more than forward correspondence on to the Investigating Officer (he did not know how the investigation was progressing), though made excuses for his failure to respond/update, being that he was an operational Inspector implying his workload left him no time to deal with the complaint. The PSD being conscious that the allocation to this officer was inappropriate adds to the evidence that the completely unacceptable delay had been deliberately engineered to cause injustice and therefore amounted to criminal misconduct (see further admission that the choice of officer was inappropriate, para 24 below). 14. The PSD’s 16 February response did not address PA’s concerns about the two false witness statements made by members of the public (it had still not been confirmed that these crimes had been recorded). He formally submitted an on-line report on 29 February alleging perjury with regards the false accounts produced by the witnesses. He informed Humberside Police’s PSD of this on 4 March and attached a copy of the report. He also informed the caseworker that he had submitted an on-line report alleging collusion between the police, CPS and Courts which was relevant to his police complaint (a copy of the report dated 28 February 2016 was also attached). 15. The Police responded on 11 March 2016 in respect of the on-line crime reports and reiterated that the police force does not investigate allegations of perjury unless a request to do so

- 9. 8 comes from the court. It was advised that PA raised these points with the courts and referred to the letter sent to him dated 13th January 2016 which gave the same advice in respect of the perjury allegations made about North East Lincolnshire Council. In response, PA suggested that the police contact the court as he had already done so regarding the false statement made by the Council and in doing so completely wasted his time. The PSD responded on 24 March 2016 in respect of the 4 March 2016 correspondence advising that the allegations made within his complaint against the Police were not recorded as a crime as perjury is not a victim based crime. 16. PA continued to raise concerns about irregularities in the Magistrates’ court proceedings as they became evident, his most recent being an email he sent to the Legal Team Manager on 28 March 2016. He had discovered that the relevant Criminal Procedure Rules require that when a defendant is absent the court must proceed as if he were present and had pleaded not guilty. Also there was provision under the Magistrates’ Court’s Act 1980 for a defendant to be tried on the papers alone. He contended that this would have been the procedure most in the interest of justice as he was disadvantaged by having no legal representation and in the dark as to his rights. He had submitted various documents of mitigating evidence which would have been impermissible for the court to ignore had the case been tried on the papers and plainly would have been the fairer option. Having taken this into account along with the prosecution’s lack of evidence and the questionable, inconsistent witness statements, the court could not conceivably have found a verdict of guilt. 17. He went on to say that the court had no power to find a guilty verdict merely on account of the defendant’s failure to appear nor did the absence justify the judge allowing the solicitor, who had been appointed to cross-examine the police and witnesses to withdraw from the case (it must proceed as if the defendant were present and pleaded not guilty). He also discovered that the bundle he was handed by the usher minutes before the 30 September 2015 court hearing contained documents (material to the case), that apparently required serving in a prescribed manner by the CPS which would not have entailed passing them on last minute with no explanation as to their importance. In among the papers he was handed by the usher was a letter (to defence where there is material to disclose) dated 22 September 2015 that evidently required serving along with other material and should have alerted PA to any implications of not being legally represented. The letter stated ‘I am required to disclose to you any prosecution material which has not previously been disclosed, and which might reasonably be considered capable of undermining the case for the prosecution or of assisting

- 10. 9 the accused’s case’. The letter also set out the legal requirement for submitting a defence statement among other instructions that he should have known about before his court hearing of 22 September 2015. The failure to properly serve these documents clearly disadvantaged PA not least because a schedule of unused material it referred to contained material considered capable of undermining the case for the prosecution. 18. He stressed that the failure to explain and correctly serve the documents reinforced his assertion that the authorities were complicit in disadvantaging him to the greatest extent possible as a means to succeed in falsely criminalising and defrauding him. His rights were further denied in respect of the sentencing hearing on 22 December subsequent to being duped into opening the door to warrant officers who falsely claimed they were the police and coerced him into attending court. He was locked up again and told while awaiting the hearing that he would have access to the duty solicitor, however, this was untrue, he was not legally advised but led directly to the courtroom in handcuffs to be sentenced for his wrongful conviction. 19. The court responded on 12 April 2016 justifying how it was able to convict PA in circumstances where it was inconceivable that the judge was sure of his guilt. According to the Legal Team Manager it was possible because the judge was able to deny the existence of material in the case file that undermined the prosecution because evidence of it was not presented in person by PA in court. In other words, all that really matters is the perception witnesses attending the hearing have of the judge’s certainty of a defendant’s guilt (even if they are improperly informed); how sure the judge actually is himself does not come into it. He reiterated that, PA made the conscious choice not to attend court for his trial (for whatever reason) and the solicitor who attended to cross examine the prosecution witnesses on his behalf had no option but to withdraw from the case as he was not there to tell him what questions to ask. He was unable to explain why PA was not given access to the duty solicitor at the sentencing hearing on 22 December but stated that there was no question of him being defrauded or falsely criminalised as he had suggested. He reiterated that his option was to appeal against his conviction and sentence to the Crown Court. 20. PA appealed the Magistrates’ decision to the Crown Court on 12 April 2016 with an application for permission to appeal out of time. The appeal grounds to a great extent consisted of the anomalies and failings that PA had already raised with the Magistrates court’s Legal Team Manager. However, leave to appeal was refused on 15 April 2016 on the

- 11. 10 basis that PA had deliberately absented himself from trial and he had put forward no adequate reason as to the appeal being almost 3 months out of time. Evidently the Crown Court deemed PA’s complete lack of confidence that he would receive a fair trial was not a good enough reason for refusing to stand before the District Judge. His reasons for why he was appealing out of time were attributable partly to his lack of knowledge of the criminal justice system and being given no information regarding his legal rights. Other than that he had carried out his own investigations; researched the law and had engaged with the Magistrates’ court which far exceeded the 21 days time limit within which PA would normally have had to appeal (he had relied on satisfying the Magistrates’ court that it would be appropriate to reopen the case). 21. PA had still not received an outcome to the 8 November 2015 police conduct complaint and therefore prompted the PSD for an update regarding the progress of the matter on 3 May 2016. He alerted the force to some information he had discovered on the CPS’ website which questioned the force’s motivation for not investigating the allegations of perjury. The force had previously stated and maintained that, ‘Humberside Police do not investigate allegations of perjury unless a request to do so comes from the court themselves’. However, the CPS states that: “Where a judge or magistrate believes that some evidence adduced at trial is perjured s/he can recommend that there should be a police investigation. The absence of such recommendation does not mean that there is no justification for an investigation.” 22. PA wrote to the Magistrates court on 9 May 2016 to express his view that he was able to resume his attempts to get answers regarding the criminal way the court, police, CPS and judges had dealt with this matter because his appeal options were exhausted. He criticise the court’s rationale for refusing to reopen the case particularly for not taking into account relevant factors. He reiterated his concerns about it being unreasonable to have expected him to be tried by the same judge who he had complained about to JCIO (and the police), his representations not being taken into account and the witnesses lying in their statements. He objected to the court taking the view that he should have incurred the cost of appointing a solicitor as a consequence of the corrupt police force (the police should have been investigated for the alleged inciting of the witnesses to produce false statements). He went on to say that the prosecution could not have proven the case beyond reasonable doubt, not if the evidence had been considered, particularly the clearly inconsistent witness statements (he

- 12. 11 would have been alerted to the conviction being unsafe). He suggested that the reason why his written evidence was considered inadmissible was a ploy to conceal the facts from attendee witnesses so as to justify his verdict of guilt. He viewed that the Crown court refusing the appeal left the Magistrates’ court no alternative than to overturn the decision under s142 of the Magistrates’ courts Act 1980 as it was aware from all the evidence that the conviction was unsafe. 23. The Legal Team Manager responded 20 May 2016 reiterating that the court was not prepared to reopen PA’s case (because he deliberately chose not to attend the trial). The concerns regarding the criminal way the court, police, CPS and judges had dealt with the matter were not addressed, they were merely dismissed as being outrageous. 24. PA asked the force on 13 October 2016 whether the Investigating Officer who was referred the complaint had been instructed to discontinue the investigation as he had still not received an update in respect of the 8 November 2015 police conduct complaint. He should have been updated by 26 January 2016, assuming the clock started ticking when the Investigating Officer was forwarded the complaint file. An update should be provided every 28 days from that point, or, according to the IOPC, from when a complaint has been formally recorded under the Police Reform Act 2002. The force’s 31 October response (below) reinforced the view that the choice of officer to investigate was inappropriate: “Insp Parsons has not been instructed to discontinue the investigation. As a duty inspector, Insp Parsons is responsible for managing demand and resourcing; therefore the delay in dealing with your complaint is due to high workloads and back log and will endeavour to deal with your complaint when the opportunity arises.” 25. This and a telephone query made around the same time plus further calls made on 23 and 24 November 2016 were further opportunities for the force to assess the situation and conclude it totally unacceptable to allow it to continue. Despite receiving an apology for the lack of contact in January 2017 when the file was opened, there was still no update after another officer spoken to on 27 February 2017 assured me that he would get a message to the Investigating officer. If as the IOPC had stated a complainant should receive an update on the progress every 28 days once a complaint had been formally recorded, there should roughly have been around 17 updates, however, only one contact had been made (4 January 2017).

- 13. 12 26. Several individual complaints were submitted to the police in quick succession each concerning different aspects of the PSD’s failure over a period of 400 days to complete its investigation into the 8 November 2015 conduct complaint. For example, the Investigating Officer had failed to investigate the complaint and never once provided an update; the PSD failed in its duty by not supervising the investigation; PA was never contacted on any of the occasions he was informed by the person he made enquiries with that that they would get the Investigating Officer to do so. The force consolidated the complaints and recorded the concerns in respect of a submission date of 24 December 2016 and the concerns deemed suitable to be dealt with by way of Local Resolution. 27. Shortly after (4 January 2017) the Investigating Officer sent an email of apology in respect of the 8 November 2015 conduct complaint and admitted that he had just opened the file for the first time (372 days after he had been allocated the case on 29 December 2015). In the meantime, in respect of the of 24 December 2016 submission the force determined in an outcome of 13 March 2017 that the PSD had done everything within its power to ensure the investigation was being dealt with in a timely and professional manner. However, that did not appear to have extended to anything more than passing on messages. The PSD must have been aware that the work commitments of a duty inspector would cause difficulties for a complaint to be investigated but referred the case regardless and took no initiative to reconsider the choice of officer to deal with the matter. 28. The outcome of the conduct complaint of 8 November 2015 was eventually sent to PA on 3 April 2017. The Investigating Officer found that there was no wrong doing by the arresting officer or any other parties involved in the matter (based on all the information available to him). He considered that the Local Resolution process (the way he had dealt with the complaint) was a suitable course of action in the circumstances. The outcome letter informed PA that he was able to appeal the decision but to Humberside Police (not the IOPC) as his complaint did not justify criminal or misconduct proceedings. Legislation governing the complaint process does not allow any intervention of a decision like this to be put right until the Local Resolution process has completed, therefore, from when the police wrongly classified the complaint until he was given the opportunity to challenge the decision PA had to wait 461 days. However, if you include the aggregate 51 days that it took for the PSD to record the complaint and the period it had been unlawfully suspended this extended to 512 days. He had been caused gross injustice because a flaw in the complaint’s procedure

- 14. 13 enables a PSD to classify a complaint, which the law requires to be fully investigated, as one which can be dealt with by way of Local Resolution. Complaint to the IOPC 29. PA had found out from research and advice from the IOPC what was required of the police for it to be compliant with the law and also how the appeal system could be exploited by the force to circumvent compliance with the same laws. For example he had learned that once a complaint has been formally recorded the Investigating Officer was under a duty to send an update on the progress of the complaint every 28 days and if a complainant is not sent a formal recording decision within 15 working days of the force receiving his complaint, or the force decide not to record it, he will have an automatic right of appeal to the IOPC to decide if it should be formally recorded. He had prior to the 3 April 2017 outcome contacted the IOPC about the delay (31 October 2016). He raised concerns about there being no outcome to the investigation despite the fact 358 days had passed since he submitted the complaint. He had telephoned the PSD earlier in October 2016 to enquire whether there was an update and informed by the caseworker that Inspector Parsons was dealing with the complaint who would be asked to contact PA (though never did). He informed the IOPC about the response he had received that day to his request asking to know whether the Investigating Officer had been instructed to discontinue the investigation (see above para 24). He considered the injustice of being wrongly convicted on false evidence etc., compounded by the subsequent failure of the PSD to take responsibility for the injustice caused by the force (and a string of other failings) warranted charges bringing against senior officers at Humberside police for Misconduct in public office. 30. The IOPC responded on 2 November advising PA that the Police Reform Act 2002 does not state that an investigation should be concluded within a certain time frame (each complaint is different and would be impractical for them to be dealt with within the same time frame). It went on to say that the IOPC could not intervene in an ongoing investigation and could not take any further action in relation to the matter. He was advised he would be provided an appeal right at the end of the investigation and to raise his concerns then should he choose to go down that route. 31. PA emailed a response on 20 November to put the IOPC in the picture regarding its statement about being unable to intervene in an ongoing complaint because of an omission in the Police Reform Act 2002 requiring an investigation to be concluded within a certain time

- 15. 14 frame. He advised them that it was unlikely that the police had even begun the process as it had stated that the Investigating Officer ‘will endeavour to deal with it when the opportunity arises’ (see above para 24). He went on to say that the 358 days already gone by since the complaint was submitted pointed to an abuse of the complaints procedure and it was the abuse that was the issue not the IOPC’s non intervention in an ongoing complaint. It is of note what the IOPC advises in its “Focus” series of guidance in respect of complaints being investigated in a timely manner (regardless of there being no time limit). Though the December 2016 Focus issue 10 had not been published at that point in time the relevant content is below: “There is no time limit for how long an investigation should take to complete – this will obviously depend on the specifics of the case. However, all appropriate steps to investigate complaints should be taken in a timely manner. This builds the confidence of the complainant and the officers/staff under investigation, as well as ensuring the integrity of the evidence. When investigating a potentially criminal allegation, [Investigating Officers] should also be mindful of any statutory time limits for bringing a prosecution.” The IOPC does not consider the lack of provision for an investigation to be concluded within a certain time frame to be a green light for proceedings to be delayed for so long that by the time they have concluded any legal proceedings regarding the breach of Human Rights that a complainant may have intended bringing upon the outcome, would be statute barred. 32. He asked for his concerns to be escalated to a person with the appropriate seniority and responsibility to address the serious matters raised and who would not simply consider it an attempt to circumvent the appeal process. He expressed his view that it would not have been parliament’s intention when enacting the Police Reform Act 2002 that it should function as a universal get out clause for the IOPC holding police force’s to account. He said in respect of the advice that he should raise concerns (in his appeal) when the opportunity arose at the end of the investigation that he had done that once before and his concerns were ignored. He also reminded the IOPC about its own published statistics which revealed that Humberside Police was one of the worst forces in the country with zero upheld appeals out of 106 complainants who were unhappy with how their concerns were dealt with. 33. The IOPC’s response of 25 November was no help either. It reiterated that it was required to act according to its role as set out in the Police Reform Act 2002 (it could not act where the relevant authority to deal with a complaint/appeal, is the police force). It further advised that

- 16. 15 PA should raise concerns directly with the PSD about the way the complaint had been handled. In relation to his dissatisfaction with the complaints process, it suggested he raise these concerns with his MP, as it is they who are able to influence legislative changes. 34. PA persisted with his complaint to the IOPC next writing on 4 December 2016. He insisted that he was not asking for advice, nor did he expect the IOPC to intervene in the complaints/appeal process. He was alleging serious misconduct of officers serving with Humberside police therefore the legislation governing the complaints process was of no relevance. He explained in respect of the suggestion to contact the PSD directly that he had in fact done so in October and a further two times in November but had achieved nothing. He suspected that the PSD had been instructed to palm off any queries relating to the matter. He perceived that as soon as you engage with the police in a complaint the injustice suffered increases tenfold because of the statutory framework of the complaint procedure (the police exploit this to the detriment of the complainant). They would for example record a complaint wrongly to deny an appeal right and/or prolong the process over several months or even years with no intention of properly investigating it. He asked again for his complaint to be escalated to someone who would consider his actual concerns rather than brush them off as an attempt to circumvent the appeal process. 35. The IOPC’s response of 15 December exhibited the same inflexibility, i.e., it continued to view PA’s enquiries as a way of circumventing the appeal process. It acknowledged that his frustrations with the police complaints system were warranted, though in truth it was the flagrant abuse of the complaints system which amounted to criminal misconduct that needed addressing (not strictly the complaints system). The IOPC said it was not possible to have the complaint escalated and reiterated that because the complaint was with the PSD of Humberside Police it could not intervene in the matter (the process is set in legislation therefore it could add nothing further). Ultimately the IOPC stated that any further email it received in respect of the matter may be filed and not responded to. 36. PA decided he would no longer pursue his complaint with the IOPC, however, because of a misunderstanding it had inadvertently resumed. A new unrelated complaint emailed on 4 January 2017 by PA to the PSD (copied to the IOPC) advised the force that if he did not receive a formal recording decision within 15 working days he would have an automatic right of appeal to the IOPC to decide if it should be formally recorded. The IOPC replied on 17 January 2017 under the misapprehension that PA had made an enquiry about how his

- 17. 16 new conduct complaint would be handled. It reiterated what had already been provided in various previous correspondence, i.e., (i) the force had 15 working days to make a formal recording decision, (ii) there was no time limit for the completion of an investigation and (iii) there was a right to appeal to the IOPC about the police’s recording decision. However, it was stated additionally that ‘once a complaint has been formally recorded under the Police Reform Act 2002 you should receive an update on the progress of your complaint every 28 days from the Investigating Officer’. 37. PA replied on 25 February 2017, taking the opportunity to raise concerns about the failure of the Investigating Officer to give an update on the progress of a complaint every 28 days but in relation to the 8 November 2015 conduct complaint. He explained that the last contact he had with the Investigating Officer was 9 January 2017 and he had been informed by him only days earlier that the complaint file was opened for the first time on 4 January 2017 (the complaint was submitted in November 2015). He asked whether it was likely that the force was deliberately attempting to cause him as much injustice as possible and if so would there be any action the IOPC could take against the force. 38. The IOPC responded on 8 March 2017 and confirmed that they had written to Humberside Police’s PSD on 1 March 2017 to request an update on the conduct complaint of 8 November 2015 and was awaiting a response but had chased them again that day (they would write again once they had an update). However, the IOPC did not write again, perhaps because the PSD never replied but in any event the complaint outcome was sent approximately a month later. Returning to the Local Resolution outcome 3 April 2017 39. As stated (above para 28) the outcome of the conduct complaint was eventually sent 3 April 2017. PA replied on 5 April 2017 to the IOPC’s 8 March 2017 correspondence referring to the outcome he had received the from Humberside police. He expressed his obvious dissatisfaction with the fact that he had to wait over 500 days to obtain it, but to learn that the investigation had been a sham just added insult to injury. He said he intended to appeal the decision but was concerned about whether the complaint was suitable to have been dealt with by way of Local Resolution. He had checked his records and found a letter dated 29 December 2015 from the force which stated that the complaint was considered suitable to be dealt with that way. He queried whether there should have been a full investigation, bearing

- 18. 17 in mind how serious the consequences had been for him and that the various matters if proven would have had criminal consequences for those involved. He mentioned an IOPC publication he had seen (practical guidance on handling complaints) which included a test for establishing whether a complaint was suitable for Local Resolution or Investigation. He located the document and quoted the relevant part of the test for assessing suitability for local resolution, as quoted from the August 2014 issue (Focus), which is as follows: “The suitability test A complaint is suitable for local resolution if the appropriate authority is satisfied: a. the conduct being complained about, even if proven, would not justify criminal or disciplinary proceedings against the person being complained about...” He wanted to know before beginning work on an appeal whether the force should have been more diligent in determining the suitability of its approach to dealing with his complaint and if there was a possibility that the force reviewed the matter. He attached the 8 November 2015 complaint and the letter of 29 December 2015 that stated that the complaint was considered suitable to be dealt with by Local Resolution. 40. The IOPC replied on 5 April 2017 under the misapprehension that PA had submitted his appeal to them rather than making an enquiry. He had clearly not submitted an appeal because he stated in his enquiry ‘I would like knowing before I begin work on an appeal...’ He wrote back and explained that he had not submitted an appeal that day; rather he had made an enquiry which he wanted addressing before he made his appeal. He asked if someone would consider what he had actually enquired about in his email of 5 April 2017. 41. The IOPC replied on 6 April to say it was unable to comment on whether a complaint is suitable for local resolution where it was not the relevant appeal body. It advised that if PA disagreed with the Force’s decision to locally resolve the complaint, this would need to form part of his appeal. It reiterated that he would need to contact the force directly as they had decided that they were the Relevant Appeal Body to consider his appeal and there is no right of appeal to the IOPC. PA wrote back thanking the IOPC for clarifying the matter and said he would raise the issue in his appeal but would however appreciate being provided the information he was seeking as a response to a general enquiry.

- 19. 18 42. The IOPC wrote back responding to the queries PA raised in his email of 5 April 2017 and advised that when the IOPC are not the relevant appeal body it cannot have any involvement in the case. It referred to the suitability test PA had queried which states that ‘a complaint is suitable for local resolution if the appropriate authority is satisfied…’. It emphasised that the IOPC were not the appropriate authority therefore, if PA wanted the force to review the matter, he would need to put this request forward to them. It added that the force do not require consent to deal with a complaint via local resolution, therefore if he did not feel that local resolution was appropriate, he should raise this as part of his appeal (it could not comment any further). The IOPC was unable to (or would not) comment on the obvious fact that the PSD had unlawfully opted for local resolution – a decision requiring the officer making it to have genuinely believed that a police officer proven to have incited a witness to commit perjury would not have justified criminal or disciplinary proceedings. 43. PA contacted the PSD on 7 April 2017 to query the 3 April 2017 local resolution outcome. He raised the same concerns he had done with the IOPC on 5 April except he was not seeking advice on the matters, rather he was asserting that the legal test to determine whether the complaint was suitable to be dealt with by local resolution had been misapplied. He stated that if the ‘suitability test’ had been properly applied, the most suitable course of action in the circumstances would have been a full investigation. The PSD caseworker wrote back simply stating ‘as per the documentation sent to you, you have the opportunity to appeal. Please follow the information on the fact sheet should you wish to do so’. 44. PA responded (7 April) to say that he had taken advice from the IOPC regarding asking for a review (the force had so obviously proceeded with the wrong process). He suggested that the force would not have been ignorant of the fact that a full investigation was required and the legislation governing misconduct complaints had been intentionally abused. He said that an aggrieved person having an appeal right did not justify the PSD routinely recording complaints wrongly or incorrectly opting for Local Resolution (it amounted to an abuse of position for an officer to intentionally cause further injustice). Engaging in the appeal process was not an insignificant undertaking which sometimes drag on for years. He reminded the PSD that it similarly opted to deal with another of his concerns by way of Local Resolution which should have been rigorously investigated because of the severity of the misconduct. He considered having to engage further in the process on account of the routine abuse of the Police Reform Act 2002 was a further injustice. There is no record of the PSD caseworker replying.

- 20. 19 45. The outcome was appealed on 22 April 2017 on the grounds that the statutory conditions were not met for the complaint to be dealt with by Local Resolution (it required fully investigating by law) and that the outcome did not reflect the evidence available. The witness statements were discredited for being inconsistent and manifestly contrived. It was suggested that the police may have a collection of standard “off the shelf” phrases that can be incorporated into their statements for effect. A phrase claimed by the arresting officer in his statement to have been said by PA was highlighted (“you can’t make me”) which PA disputes to have said. This was coincidentally what was purportedly said to an officer in relation to a separate incident alleged to have taken place on 27 December 2015 according to the local press. The Code for Crown Prosecutors and the Director of Public Prosecution’s Guidance on Charging were argued to have not been complied with (the prosecution was proceeded with where the evidence fell way below the standards which would be expected for a fair trial). There was no realistic prospect of conviction based on an objective assessment of the evidence assuming the case would be heard impartially by a reasonable judge properly directed and acting in accordance with the law. 46. The anomaly was raised about why no CCTV footage was asked to be retained when 7 cameras covered the relevant areas. PA was denied being informed of his rights to legal representation, he was not aware of the position regarding his rights generally and it was not explained to him the process other than being told dates on which he needed to attend the police station or court. Representations he submitted to the Crown court accompanied the appeal which set out in more detail the CPS obviously breeching its own code regarding information it was required to disclose to him that was considered capable of undermining the case for the prosecution or of assisting his case. He argued that the failure to explain and correctly serve these documents reinforced his assertion that the authorities were complicit in disadvantaging him to the greatest extent possible and everything else pointed to the CPS and court colluding with the police in a malicious prosecution. 47. Humberside Police referred the appeal to the IOPC around 6 weeks later on 5 June 2017. It was expected that the force would have deemed it appropriate to deal with the appeal itself, however, the PSD stated that it had been forwarded to the IOPC as it was the correct appeals body (based upon the wording of the complaint). 48. All the while PA was engaged in addressing the November 2015 conduct complaint he was having to juggle other matters he had raised with the force. In order to keep this background

- 21. 20 account manageable those issues will be referred to only generally where the need to becomes unavoidable. Here it is necessary to refer to two emails sent to the IOPC on 4 and 8 June 2017 which were responded to on 13 June and had been filed under the IOPC’s reference number for the November 2015 conduct complaint (though they referred to separate matters). The 4 June 2017 email related to the complaints PA had submitted to the PSD about the failure over a period of several hundred days to progress its investigation (see para 26 above). The outcome had since been challenged predominantly on the basis that it was unsuitable for Local Resolution and the Investigating Officer had not even opened the complaint file until 370 days after he had been referred it (the appeal was not upheld). PA had attached the papers in order to seek the opinion of the IOPC as to whether the force failed to reach a correct decision based on the Statutory Guidance. He had quoted what he had previously been advised by a Customer Contact Adviser to justify his potential request for the IOPC to intervene: “The [IOPC] can sometimes contact the force if it can be clearly shown that the police force (appropriate authority) has failed to reach a correct decision based on the [IOPC] Statutory Guidance. This could result in the force changing its decision. The [IOPC] cannot unilaterally make the force change its decision.” 49. The 8 June email was sent on advice given by the force. PA had made criminal allegations against the Investigating Officer and head of the PSD relating to the handling of his conduct complaint of 8 November 2015 via the facility for reporting crime on the force’s website on 4 June 2017 (not a conduct complaint). The force telephoned PA on 8 June informing him that the matter would be referred to the PSD who would likely refer the matter to the IOPC but recommended he also send the IOPC details. PA did as advised and provided a copy of the crime report. 50. The IOPC’s 13 June response was no help in respect of either of the queries. The papers relating to the first query explained why it was inappropriate to conclude that the complaint could not result in misconduct or criminal proceedings purely on the basis that there is no time limit on how long the PSD take to deal with a complaint (re, Focus issue 10 - para 31 above). The appeal, which was included in the papers submitted to the IOPC for its opinion contained the following representations: “It is no defence to say that there is no provision under the Police Reform Act 2002 for an investigation to be concluded within a certain time frame. It is understood that there

- 22. 21 is no provision because it would be impractical to expect all matters to be dealt with within the same time frame as all complaints are different. However, a delay caused by the investigating officer not opening the file until 370 days after he had been allocated it can not be attributed to the complexity of the complaint. A letter of 29 December 2015 stated that the file had been forwarded to Inspector Parsons to be dealt with but the first contact he made regarding the complaint was an email sent 4 January 2017 in which it was stated that the file had only been opened for the first time that day.” 51. However, the IOPC failed in its response to take into account two key factors. It had (i) overlooked its own guidance, which had by that time been published which was that ‘all appropriate steps to investigate complaints should be taken in a timely manner’ and the time taken ‘will obviously depend on the specifics of the case’, and (ii) ignored the fact that the Investigating Officer had sat on the case for 370 days without even looking at it. Its response particularly regarding these points was as follows: “I note from your email that you have queried who should be the relevant appeal body for your police complaint. I note from the attached complaint form that your complaint was regarding the length of time the [PSD] have taken to deal with a previous police complaint...., stating that over 400 days have passed since you first submitted the complaint, and failing to keep you update with its progress. Please be aware that there is no time limit on how long the PSD take to deal with a complaint, therefore your complaint could not result in misconduct or criminal proceedings. Consequently, the [IOPC] would not be considered as the relevant appeal body in this case.” 52. The rest of its response regarding this query was advice to PA that the IOPC could not intervene (there was no further right of appeal) and of his options if he disagreed with the appeal decision, as quoted below: “Whilst I note you remain dissatisfied with the decision made in regards to your appeal it is not within the remit of the [IOPC] to assist you in this matter. Please note the Police Reform Act governing complaint procedures does not afford you a further right of appeal against this decision through the PSD of Humberside Police or the [IOPC]. You may however wish to challenge the appeal decision through judicial review. For further information on this process please seek independent legal advice.” It would constitute misconduct if a public officer entrusted to act impartially, fairly and without discrimination or bias was found to have wilfully neglected to act as required. Leaving someone who has clearly been caused severe injustice by a public authority no

- 23. 22 alternative to a possible remedy than to pursue it in the high court when its decision was indisputably wrong can not be considered free of association with misconduct. 53. The 8 June 2017 email informed the IOPC about the telephone call PA had received that day from the force about an alleged crime he reported on 4 June 2017 and that the PSD would be dealing with the matter and would likely refer it to the IOPC. The attached 4 June 2017 crime report (log 343 of 5th June) contained the following: “I am reporting what I believe is a crime that has been committed against me by Humberside police in allowing a complaint about the conduct of PC Thomas Blake to have prolonged over a 510 day period (8 November 2015 until 3 April 2017). My 8 November complaint alleged wrongful arrest and false imprisonment and expressed my suspicion that the arresting officer incited a witness to commit perjury. The witnesses had committed criminal offences by making false allegations which were backed up in detailed statements to the police. Consequently they were liable to imprisonment for perverting the course of justice and clearly should have been investigated by the police and prosecuted by the CPS (neither happened). Inspector Andrew Parsons who was referred the complaint (the resolving officer) had not even opened the file until 370 days after it had been allocated to him. Therefore the delay could not have been attributed to the complexity of the matter. The [PSD] defended the resolving officer implying his workload left him no time to deal with the complaint which suggests that the [PSD] were conscious that the allocation to this officer was inappropriate and could have been deliberately engineered to inflict the maximum injustice. Notwithstanding the incalculable amount of time I have had to dedicate/waste on account of Humberside police’s negligence and dishonesty, I have been denied my legal right to legal remedy because of the delay. For example, it has benefited the force by ensuring that by the time investigations had completed any legal proceedings regarding the breach of Human Rights that I may have intended bringing upon the outcome, would be statute barred. I therefore allege that Inspector Andrew Parsons and Chief Superintendent Judi Heaton (head of the [PSD]) are complicit in abusing their positions for the purpose of achieving a detriment to me for which they are liable to imprisonment under the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015. Humberside police Telephoned 8/6/2017. Said the matter would be referred to Professional Standards but recommended the [IOPC] was sent details as well.”

- 24. 23 54. The IOPC’s 13 June response did not give confidence that the issue had been carefully considered. It noted from PA’s email of 8 June 2017 that he had submitted a new complaint to the PSD on 4 June 2017 when in fact he had made criminal allegations that carry a prison sentence under the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015 against the Investigating Officer and head of the PSD. However, even if the IOPC had erroneously considered it to be a complaint under the Police Reform Act 2002, it was a scandalous show of indifference for an organisation whose statutory duty is to secure and maintain public confidence in the police complaints system to have not found it necessary to intervene. Its response regarding this query continues as follows: “Normally this complaint would be forwarded onto the PSD of the appropriate police force for their consideration. We note that your correspondence has already been sent to the police and we will therefore be taking no additional action.” 55. PA responded on 30 June 2017 to clarify that the complaint which the IOPC referred to dated 4 June 2017 was in fact a reported crime which was submitted on Humberside police’s website and that the force rightly or wrongly treated it as a complaint. He said regarding the complaint taking over 500 days to be addressed that he had already been informed in an email dated 17 January 2017 (see para 36 above) that there was no time limit on how long the PSD take because every complaint is different and varies in complexity. He stated that the a delay caused by the investigating officer not opening the file until 370 days after he had been allocated it could not be attributed to the complexity of the complaint; he had expanded on this in the papers he had sent earlier for the IOPC’s opinion which suggested that the delay was engineered. 56. The 11 July 2017 response demonstrated without question that the Customer Contact Advisor was under orders to deflect any issues wherever possible that might otherwise have increased the workload for the IOPC. She had achieved this by focussing on content she was able to exploit whilst overlooking the salient points as the response below testifies: “I note from your email that you wish to clarify with us, that your police complaint was actually a report of crime, which has been wrongly treated as a police complaint. Please note that the [IOPC] does not get involved with criminal matters i.e. we have no power to intervene in or change the outcome of a criminal investigation, we solely deal with cases of police misconduct. I would therefore advise you discuss any criminal matters you have or wish to report with the police directly.

- 25. 24 I have filed your correspondence under the above reference number and will be taking no further action.” PA replied simply to thank the Customer Contact Advisor for her response but expressed that he had evidently failed to make himself clear in his 30 June correspondence. 57. PA sent additional information to the IOPC on 13 July 2017 to supplement his 22 April 2017 appeal because he had in the meantime received a relevant Decision Notice (28 June 2017) from the Information Commissioner relating to a Freedom of Information Request he made to Humberside Police (he provided the decision). He had made the request in the hope of obtaining evidence to support his assertions that the police officer’s Witness Statement relating to his wrongful conviction contained inaccuracies. He had provided in his 22 April 2017 appeal a possible answer for why the arresting officer stated in his written account that PA had replied to him ‘you can’t make me’ when he disputes having said this (re, incident reported in local press - above para 45). The news article reported that a Humberside police officer had been assaulted and the exact phrase was supposedly said by the accused as the one in question, i.e., relating to PA’s wrongful conviction. 58. It occurred to him that it might have been a standard phrase used by police in their witness statements and wanted to know if it formed part of a collection of ‘off the shelf’ phrases they slipped into their statements for effect. He therefore requested the number of times the phrase “YOU CAN’T MAKE ME” appeared in police officers witness statements and for disclosure of the officer who included the expression where it was found in a statement. The force refused to answer the request on the grounds that it was vexatious and the Commissioner who had been subsequently referred a complaint agreed with the police that there was no serious purpose and upheld its decision that it applied the vexatious exemption correctly. Ironically the outcome was useful, despite the Commissioner upholding the vexatious exemption because it inadvertently revealed that the police officer who PA had alleged to have inaccurately set out his Witness Statement relating to his wrongful conviction was the same constable involved in the aforementioned news article. His point was that the use of standard (not necessarily true) phrases were possibly being incorporated into Witness Statements to the detriment of the defendant. The IOPC confirmed in an email of 19 July 2017 that they had received the additional representations and had been added to the case and would be reviewed once it is allocated to a casework manager.

- 26. 25 59. On completing the review (29 August 2017), the IOPC deemed the statutory conditions were not met for the matter to be suitable for Local Resolution and directed the force to fully investigate the complaint, taking into consideration further information such as evidence in support of alleged collusion between the police, CPS and Courts concerning the lack of securing CCTV and rights to legal representation etc. A complaint may not lawfully be subjected to Local Resolution if the conduct complained about is sufficiently serious to warrant criminal or disciplinary proceedings to be brought against the person whose conduct is complained of. The casework manager said she would provide a copy of the additional documentation concerning the Commissioner’s Decision Notice to Humberside Police for consideration and recommend the Investigating Officer review both sets of appeal correspondence before finalising with PA details of the complaint. 60. The casework manager commented additionally that there was insufficient evidence to suggest that a proper outcome had been reached (even if the complaint had met the threshold test to be locally resolved) and referred to Regulation 6 of the Police (Complaints and Misconduct) Regulations 2012. Regulation 6 requires that the person appointed to deal with a complaint must provide both the complainant and person complained against an opportunity to comment on the complaint. She noted, however, that there appeared to be no evidence of any dialogue between PA and Humberside Police, nor an action plan or details of what steps would be taken by the Investigating Officer to resolve the complaint. Although she had decided the complaint should be investigated, she would still provide feedback to the force about the lack of communication with PA and the importance of giving all complainants an opportunity to feed into the Local Resolution process, so learning can be taken from the case. Finally, the casework manager advised that the further complaints PA apparently had concerning both the CPS and the Court would need to be made directly to them as the IOPC had no jurisdiction. 61. The PSD wrote on 22 September 2017 regarding the 8 November 2015 complaint and appeal subsequently upheld by the IOPC on 29 August 2017 and informed PA that his complaint had been considered suitable for a proportionate investigation and would be dealt with at a local managerial level. His complaint had been forwarded to the new Investigating Officer (IO) who would be contacted in due course. 62. PA responded on 29 September 2017 (IOPC copied in) to query the decision made by the PSD that the complaint had been considered suitable for a proportionate investigation.

- 27. 26 Humberside police’s investigations fall under either one of two categories (full or proportionate). Both have prescribed procedures – the proportionate being of less scope than the full investigation thus the proportionate is more limited in scale. PA argued that the complaint ought to have been considered suitable for a full investigation on account of the seriousness of the allegations and the degree to which he had been affected by the injustice arising from the matter. He emphasised that the IOPC casework manager had recommended that the appointed IO consider the additional submissions, namely the 22 April 2017 appeal and the further representations dated 13 July 2017 which he understood to have been forwarded to the PSD. He argued further that the matter clearly warranted the most comprehensive investigation given that the additional representations dealt with such matters as collusion (police, CPS and courts), failure to secure CCTV footage, witnesses liable to imprisonment for making false allegations in detailed statements to the police and denial of rights to legal representation etc. It was also evident on exploring which issues would be relevant for investigation that there had been clear breaches of the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996. This, he said, reinforced the necessity that the matter received the fullest commitment by the force. 63. There is no record of a response from the PSD, however, the IOPC casework manager who was copied in replied on 2 October 2017. Though she noted PA’s concerns she said that the IOPC would not be commenting or giving direction regarding the scope of the complaint investigation, as they did not wish to prejudice the investigation and right of appeal that would be afforded PA at its conclusion. All they could do at that stage was place his email on the file. It had already taken 694 days from when the complaint was made until this point. The most significant factor contributing to the delay so far had been the lack of provision in the Police Reform Act 2002 to remedy an erroneous decision to locally resolve a complaint, i.e., where the requirements are not met for a complaint to be lawfully dealt with by Local Resolution. The same anomaly that led to the injustice of being tied up in a dispute with the force for almost 700 days was starting over because the opportunity to challenge the lawfulness of the investigation method does not arise until the Local Resolution process has concluded (the complainant is then able to appeal). 64. The IO who had been forwarded the complaint on 22 September 2017 made first contact with PA on 12 February 2018 and asked if he wanted to meet to discuss the issue (he replied stating that he preferred everything in writing). In reference to the IOPC letter of 29 August

- 28. 27 2017 (finalising details)8 he queried whether it was this stage the IO was presently at. He mentioned that he had been working on a paper that would contain essential factors for the investigation to take into account that focussed heavily on disclosure failures of the police. He explained that although the document was intended for Humberside police to assist in the investigation it also focused on a number of key areas considered relevant for the CPS and Magistrates’ court to examine in respect of his complaint and allegations which also focussed on disclosure failures. He said it was on the recommendation of the IOPC that he did this and quoted the relevant part of their 29 August 2017 letter which was as follows: “On a separate note it appears you may also have complaints concerning both the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the Court. As the [IOPC] has no jurisdiction over these two formal bodies, please make your complaints directly to them” He told the IO that he had almost incorporated everything he intended to include and hoped to have the document completed within the week. The IO replied to ask PA if he wanted her to wait until he had completed the representations. He agreed it was the best way to proceed and would send the supporting document to the IO when complete which he did on 19 February 2018. 65. PA forwarded the 19 February representations to the CPS accompanied by the following covering email (he did similar in respect of the court) on 20 February 2018. Dear Sir/Madam Please forward this email and attachment to the person who deals with correspondence from those wrongly convicted in respect of material which comes to light after the conclusion of proceedings (see paragraph 59 Attorney General's Guidelines). “Post-conviction The interests of justice will also mean that where material comes to light after the conclusion of the proceedings, which might cast doubt upon the safety of the conviction, there is a duty to consider disclosure. Any such material should be brought immediately to the attention of line management.” 8 ‘In the circumstances, and as part of my direction to investigate your complaint, I will recommend the person appointed to investigate your complaint reviews both sets of your appeal correspondence before finalising with you details of your complaint and what the investigation will consider’.

- 29. 28 A police conduct complaint in relation to this case was submitted on 8 November 2015 and initially dealt inappropriately by Humberside police by way of Local Resolution. The outcome provided on 3 April 2017 was appealed and referred to the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC). On completing the review, the IOPC deemed the statutory conditions were not met for the matter to be suitable for Local Resolution and directed the force to fully investigate the complaint, taking into consideration further information such as evidence in support of alleged collusion between the police, CPS and Courts. The IOPC letter upholding the appeal against Humberside police (29 August 2017) stated; “On a separate note it appears you may also have complaints concerning both the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the Court. As the [IOPC] has no jurisdiction over these two formal bodies, please make your complaints directly to them” In light of the systemic failures reported in the national press recently regarding disclosure issues it is appropriate (in addition to the IOPC recommendations) that the CPS looks again at this case. Although a defence statement I submitted unwittingly raised disclosure failures, these now have been more clearly identified and set out in the attached representations. Note: Because of disclosure failings, the defence statement was not sent to the CPS (only the court). It is noted that the Chairman of the Criminal Cases Review Commission reportedly stated that “non-disclosure of material that could prove a suspect's innocence is the 'biggest single problem’ affecting the right to a fair trial” so it is now very much in the public interest that this case is reviewed. 66. The IO acknowledged receipt of the document and said that she would go through it and be in touch. She next contacted PA on 17 April 2018 to say that she was still reviewing the document and would update him as soon as possible. On 27 May the IO produced a list of 22 key areas she believed PA considered relevant to investigate and sought confirmation from him. PA wrote back to confirm that the issues raised in the report seemed to have been covered comprehensively, though expressed his concern that a number of the issues might be filtered out for investigation because they might not be considered in jurisdiction. He asked to be informed sooner rather than later if that was the case and added that he had done as the IOPC recommended regarding making complaint to the CPS and Court separately (he had

- 30. 29 forwarded the 19 February document to both those authorities). He made further comments to assist and give additional clarity in respect of the issues that the IO had identified and itemised a number of supplementary areas to incorporate under the generally described “abuse of process” (IO’s item 9) which were as follows: Force proceeding to charge in circumstances where the law required no further action to be taken Solicitor no longer acting for [PA] (discovered minutes before the court hearing) Failure to keep case under review to assess whether prosecution material might reasonably be considered capable of undermining the prosecution’s case and whether or not it should have gone to trial Inconsistent witness statements of the Johnsons (5 day delay in obtaining Mrs Johnsons) Failure to investigate perjury allegations (the Johnsons) 67. The IO next contacted PA on 27 July 2018 to inform him that she had been consulting with the PSD as to how to go about dealing with the complaint due to the complexity of PA’s report and some items did not relate to the Police. The PSD had advised her that she was dealing with the 2 recorded allegations as below: The complainant alleges an officer unlawfully arrested the complainant for the offence of Indecent Exposure. The complainant alleges an officer has incited a witness to commit perjury. She was also advised by the PSD that if there was anything else PA wished to complain about, he would have to go through the normal route of reporting it to the PSD. She had almost completed her findings as a consequence and would update PA by the end of the week that followed. 68. It was clear that the PSD were pulling a fast one and wanted to restrict the process to investigating the allegations as they had been briefly recorded therefore disregarding even some relevant initial concerns and certainly any that had been discovered throughout the process including what the IOPC had recommended as part of their direction to have Humberside Police carry out the investigation. PA wrote back as follows: Thank you for your email.