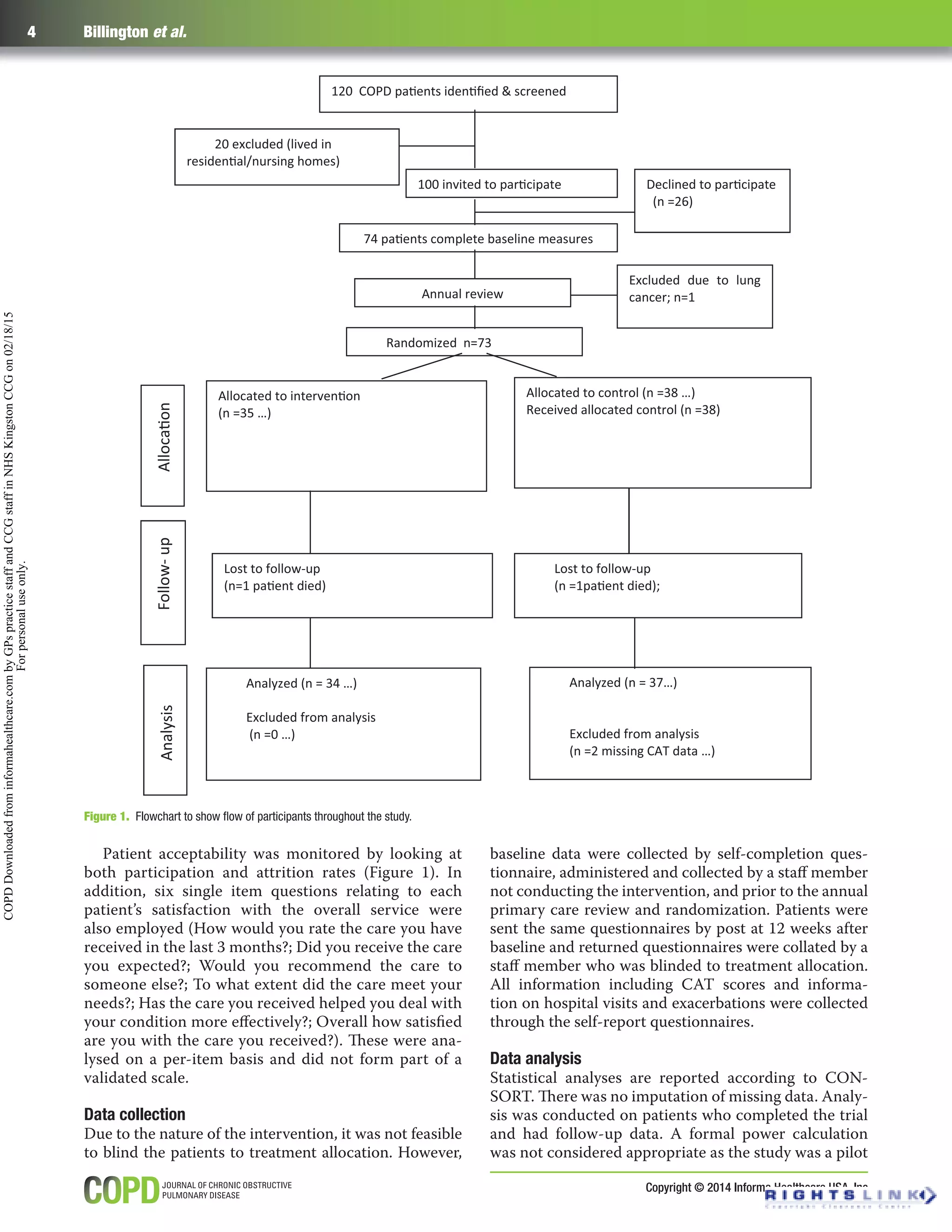

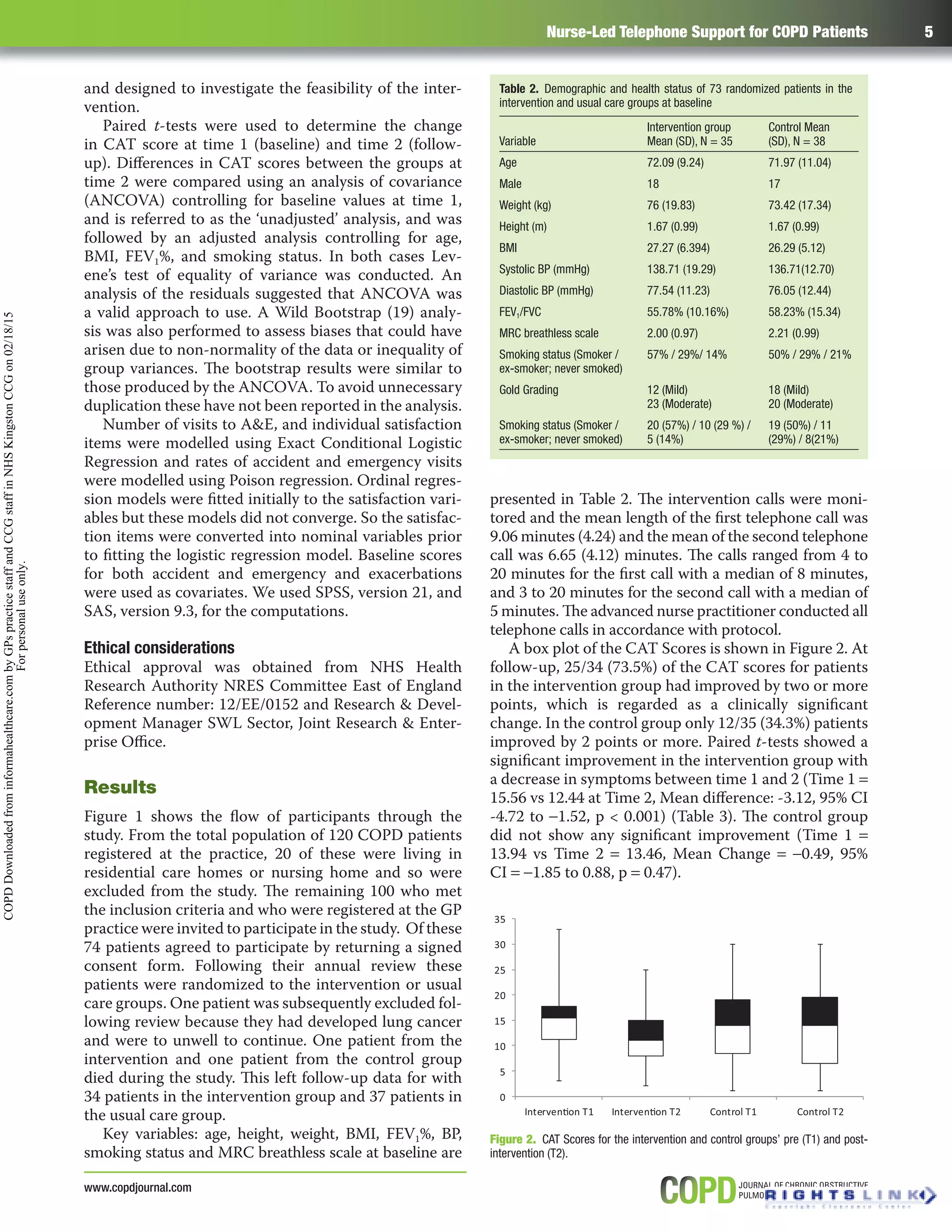

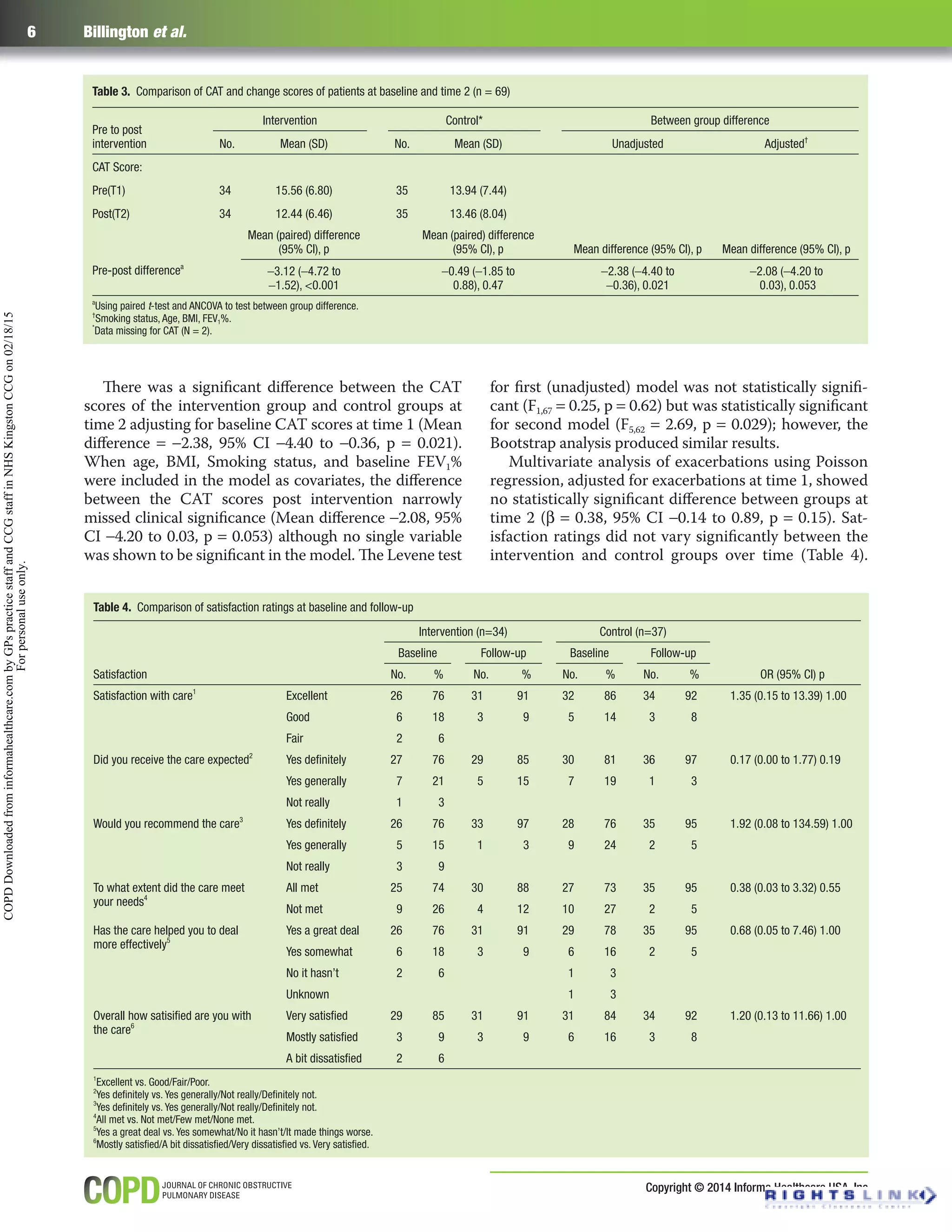

This study evaluated a nurse-led telephone intervention to support patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in managing their condition. 73 patients were randomly assigned to either receive standard care including a self-management plan, or to receive the self-management plan plus two telephone calls from a nurse over six weeks. The telephone calls provided education on using their self-management plan and managing exacerbations. The primary outcome was COPD symptom severity assessed before and after with the COPD Assessment Tool (CAT). Secondary outcomes included self-reported exacerbations and healthcare utilization. CAT scores significantly improved in the intervention group but not the control group. There were no significant differences in exacerbations between groups. Patient satisfaction did not differ significantly between groups