Jack O'Neill's Odyssey_final-3

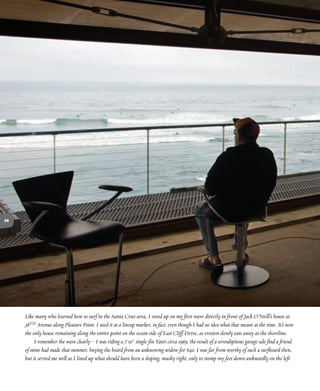

- 1. 36 Like many who learned how to surf in the Santa Cruz area, I stood up on my first wave directly in front of Jack O’Neill’s house at 38TH Avenue along Pleasure Point. I used it as a lineup marker, in fact, even though I had no idea what that meant at the time. It’s now the only house remaining along the entire point on the ocean side of East Cliff Drive, as erosion slowly eats away at the shoreline. I remember the wave clearly—I was riding a 7'10" single-fin Yater circa 1969, the result of a serendipitous garage sale find a friend of mine had made that summer, buying the board from an unknowing widow for $40. I was far from worthy of such a surfboard then, but it served me well as I lined up what should have been a sloping, mushy right, only to stomp my feet down awkwardly on the left

- 2. 37 side of the deck. The board darted back underneath my off-balance frame, and, to my surprise, I zipped along a racy left-hand wall until the wave collapsed and sent me tumbling, maybe 30 yards in front of O’Neill’s house. As I came to the surface, giddy and bewildered at the same time, I imagined that O’Neill—eye patch, sly grin, and all—was somehow watching me from the deck of his house. He could even be quietly cheering me on, I remember thinking, jazzed to witness my first ride. The rest of that summer and beyond, I would sit on my board and wait for sets, and wonder if he was there in that house...watching, silently pleased to see me—and so many other surfers before and after me—get stoked in the frigid waters of Northern California. Jack O’Neill’s OdysseyBy Dean LaTourrette Photography by Mark Gordon Jack describes 38th Avenue (aka O’Neill’s): “A good little wave...I sit and space out, see myself on the waves, ride them in my mind.”

- 4. “To hell with luck. I’ll bring the luck with me.” —Santiago/Hemingway, Old Man and the Sea By now most of us are familiar with the Jack story, thanks in part to an O’Neill marketing machine that has molded the company’s entire brand identity around the charismatic yet somewhat elusive founder of the company: experimented with early versions of closed-cell foam and later neoprene to develop some of the first surfing wetsuits; opened the world’s first true “surf shop” on the Great Highway in San Francisco, later moving the business to Santa Cruz; has created numerous wetsuit and surf product innovations over the years; wears a cool eye patch due to an accident involving a surfboard to the face, a look that has come to symbolize both his and his company’s rebellious nature; has owned some exceptional toys, including boats, hot air balloons, and numerous experimental, difficult-to- describe air and water craft... and so on. But that’s the marketing. The man himself is a bit more difficult to pin down. The image of O’Neill, Inc. has been carefully crafted around the literal and symbolic father of the company, even going so far as to invite you to “know Jack” on their corporate website. Ironically, because of this, I’m finding it difficult to get to know Jack, to delineate between O’Neill the man and O’Neill the company. Sipping coffee in O’Neill’s living room overlooking Pleasure Point, staring out at the very peak where I caught my seminal first wave, I sit across the table from him and take my best stabs. He’s looking as relaxed as ever in his trade- mark wardrobe: jeans, flip-flops, and a casually untucked button-down shirt. As we talk, he stares off into the distance—much like a skipper at the helm— save for delivering the occasional joke, when he looks directly at me with a twinkle in his eye, searching for my reaction. He rattles off a series of quotes that sound vaguely familiar. I’ve read many of them on the O’Neill website, in articles, even on some of the O’Neill products themselves: “I was just looking for a way to stay warm,” and “Things can get all screwed up, and you jump in the ocean and everything’s all right again.” Nice sentiments, yes, but surely there’s more to the story than cold water, curiosity, and luck—than surfing, bonfires, and good times. I poke and I prod but get gently deflected by his unwavering optimism. O’Neill was born in 1923, the son of a fire engine salesman from Denver. The bulk of his childhood was spent split between Portland, Oregon, and Southern California, and it was there that he first discovered the joys of the ocean. “When I was in grade school I went down to the beach in Santa Monica,” he says, “and as a little kid I caught some waves bodysurfing. And, boy, that really got me, to get those rides in the ocean. There was something about it that really grabbed me.” His family later moved north to Oregon, where O’Neill attended the University of Portland. A combination of wander- lust and patriotism led him to quit school and enlist in the Navy Air Corps where they shipped him off to, of all places, Minnesota. “I join the Navy, and they station me in the middle of the damn country!” he laments. A knee injury led to his discharge, and coming out of the service his goal was to sail around the world, only he didn’t have the funds. An uncle in New York offered him a job selling parking meters, so he went there in hopes of earning his global passage. “I only lasted a month, for the training,” he laughs. “I hated all the city politics.” Instead, O’Neill returned to the West Coast and, after marrying a Portland girl named Marjorie Bennett, settled in San Francisco in 1949. There he worked a number of jobs, the most memorable of which was crab potting out at the Farallones for what he calls a crazy Swedish boat captain. “It was tough out on those crab pot boats,” he recalls. “There was only two of us, so there was only one guy for the captain to yell at, and that was me.” He was, if you’ll pardon the expression, a jack-of-all- trades, working a variety of jobs in order to make a buck and support a family. He himself readily admits he wasn’t the world’s best worker, jumping from odd job to odd job. “As an employee, I never did make much money,” says O’Neill today. “God, I must have had 20 to 30 different jobs over the years. I was a patternmaker at a shipyard. I sold skylights, aluminum siding, and fire extinguishers. I worked for the nursery digging holes. I was a longshoreman in Portland. I was a cargo checker at the docks. I was even a bicycle messenger boy.” Ironically, it was O’Neill’s exposure to various businesses —both ocean- and non-ocean-related—that would serve him well in his future enterprise. “I got the idea of being in business for myself in my very first job: selling the Herald Express news- 39 At Steamer’s, circa late ’50s, “I was never what you’d call hot, but I could paddle well and surf the waves as big as they got around here.” April 2007. For O’Neill, Inc., Jack’s salty appearance (left) is such that it has been logo-ized. O’NEILLCOLLECTION

- 5. 40 paper in Southern California,” he says. “I bought them for two cents and sold them for three. I’d stand out on the road at Melrose and Fairfax, across from the Farmers’ Market. That was my territory—in the middle of the street!” The fishing life augmented with miscellaneous jobs afforded O’Neill enough free time to bodysurf at Kelly’s Cove at San Francisco’s Ocean Beach, and in 1952 he opened his first “Surf Shop” (as well as trademarked the name) on the Great Highway. He would open his second shop in Santa Cruz seven years later and eventually move the entire operation there. As I listen to the early portion of O’Neill’s story, it’s clear to me that he hails from a different era, one of more stoic demeanor and practiced constraint. He’s as comfortable talking about tough times as he is going to the dentist, and indeed getting him to share anything beyond the exuberant surfer’s fantasy life is like pulling teeth. Instead, he prefers to crack jokes and flash his patented grin, leaving you to wonder if anything has ever gone wrong in this man’s life. O’Neill has in fact faced both personal and professional tragedy during his career. In 1973 his wife, Marge, died, leaving him as the primary caregiver for six kids. Raising a family in Santa Cruz during the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, in part as a single father, came with inherent challenges—particularly within the raucous surfing community. Drugs and partying were rampant, and the O’Neill family was hardly immune. But with Jack O’Neill at the helm, the kids made it through relatively unscathed. “I think getting exposed to that stuff is part of growing up as a kid,” says Pat O’Neill, a one-time professional surfer who now serves as CEO of O’Neill, Inc. “I mean, during a certain time period, everyone around us was smoking, snorting, whatever. As a high school kid, though, I wasn’t out doing a lot of that stuff, I was really concentrated on surfing.” Then there were the struggles with the business itself and the matter of creating an entirely new market from scratch. “There were definitely very difficult times; that’s why I have so much respect for Jack,” says Joel Woods, a longtime family friend and early O’Neill employee. “Here he is going off into something where people are asking him who he’s going to sell to once he sells the first ten suits. He’s got six kids to feed and nothing but a lot of energy to rely on.” “Jack really bet the ranch that he could pull it off,” says Pat O’Neill. “We had a couple of really tough years, there’s no two ways about it. There wasn’t any surf industry back then, people like Jack created it. You were basically plucking people off the street to try and get them interested in surfing so you could get them to buy a board or a wetsuit.” Despite the challenges, the business did survive and eventually began to thrive, primarily due to O’Neill’s perse- verance. “Jack always knew where he wanted to go,” says Woods. “He’d get this place that he wanted to arrive at, and cast bread out on the water and see what came back. He’d decide whether it worked or not, and if it fit into where he wanted to end up, then he took that in.” “Peace comes from within. Do not seek it without.” —Gautama Buddha, “The house is alone on the cliff. When first built, it sold for eighteen-five. I got it in the ’70s for fifty. My wife didn’t like how high above the rocks it was.”

- 6. Jack O’Neill is a Buddhist. Not in a practicing, organized religion sort of way, mind you, but in the way that he lives his life—not forcing things, gravitating toward his natural interests and passions, letting things come to him versus constantly chasing after them. While his home shares hints of the philosophy in the form of subtle art and a Zen rock garden in front, and he’s been known to meditate from time to time, it’s more the innate way he lives his life that characterizes this Zen-like approach. He makes things look and sound...easy. “I really don’t know that much about it [Buddhism],” he says, “but I find meditation very relaxing. I think it helps with concentration and clearing the mind.” O’Neill’s house is not a mansion—far from it. It’s a multi-level, ocean-dweller’s dream pad, where Big Sur meets 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Indeed, with water-tight portal windows and a World War II-era submarine door (bought at a swap meet) lining a basement level that pushes close to the high tide line, the lower portion of the home resembles the Nautilus, and one could almost imagine taking the house for a day cruise through Monterey Bay. O’Neill, not unlike Captain Nemo, exudes a rebellious yet mysterious nature, combined with a strong environmental ethos. But where Nemo is a cynic and a pessimist, O’Neill is a steadfast optimist. “I get up in the morning and look out that porthole and check the surf, the weather, warm up on the trampoline,” he says enthusiastically (referring to a trampoline in the center of his house that spans three floors). “I feel really fortunate to be in as close contact with my children as I am. All my kids have been involved with the family business, which is amazing. It’s all worked out very, very well.” “The Master in the art of living makes little distinction between his work and his play, his labor and his leisure, his mind and his body, his education and his recreation, his love and his religion. He hardly knows which is which. He simply pursues his vision of excellence in whatever he does, leaving others to decide whether he is working or playing. To him he is always doing both.” —Zen Buddhist Text O’Neill is the consummate marketer, a natural businessman and self-promoter at heart. This has been apparent even from the early days, with the creative schemes he cooked up to draw attention to his fledgling businesses. From giant wooden poles with gas flames on top marking his surf shop, to a fleet of hot air balloons and “air ships” donning the O’Neill name, to the Team O’Neill catamaran (now the Odyssey) flying a three-story O’Neill spinnaker—he’s never been one to shy from publicity. In fact, if there’s a rub about Jack and his role in the surf industry, it’s that he’s drawn unwanted attention to surfing in Northern California, a region that’s notoriously reclusive. “Jack was always very visible,” says Austin Comstock, an early attorney for O’Neill and a longtime friend. “He wanted to be associated with everything to do with the water, so anytime there was an opportunity for publicity he would be there.” This type of commercialism didn’t go over well with all surfers, particularly in the early days. “The old-time surfers around here came to Santa Cruz when it was an uncrowded frontier,” says Comstock. “Many of them disapproved of the whole contest mentality, they thought that was cheesy and corrupted the whole 41

- 7. 42

- 8. 43 “Pleasure (above) is a year-round wave, gets up to double overhead in winter. Like everyday things, I sometimes take it for granted. On the other hand, when I’m someplace else I really miss it.” Jack with grandkids little Bridget and Connor (left). Their father, Tim O’Neill, holds a 200-ton license and skippers the Sea Odyssey. Steam room with Japanese soaking tub (below). “I get up in the morning, shower, and check the surf through the porthole.”

- 9. 44 On his Zen sand garden: “We put riprap along the foot of the house, some of the rocks weighed up to ten tons. I got them to drop a few over here. Everything is carefully composed. I think about how to improve it. One of the top gardeners from the Imperial Palace in Japan gives me advice.”

- 10. 45 “When I first bought the house the ocean came under it and the bank wouldn’t finance it. I removed the dirt from under the house to make this room. The house started to shift and I stabilized it with the steel pillars you see here. We have to close the portholes when the surf is big.”

- 11. activity. Then you had Jack commercializing and supporting those contests and supporting his products—it wasn’t unfriendly —they just didn’t go for that. For them it wasn’t what surfing was all about, and that was just something Jack had to deal with.” Of course, considering that when he began his business there were only a handful of surfers anywhere north of Point Conception, he was forced to not only promote his company and its products, but the sport of surfing itself. The way he figured it, the only way he was going to increase wetsuit sales was if the total number of cold- water surfers grew. “I think there were a lot of people who were just jealous,” says Bill Hickey, one of the original Kelly’s Cove surfers, who managed O’Neill’s San Francisco shop in the early ’60s. “Some of these people, you know, they see somebody like Jack doing all these things when they themselves aren’t doing anything. So they come out with all this negative crap, calling O’Neill a sellout and all that. I mean, somebody had to do it, man. We were freezing our asses off out there!” From the O’Neill Archives Jack helps Chubby Mitchell at Steamer’s, circa ’50s. “This was Steamer’s before the riprap went in. The down-south guys called us cliff surfers because we’d jump off. We eventually replaced the rope with a fire hose to help us get back up.” Pat skating in front of the first O’Neill shop at Cowell’s Beach, circa mid-’60s.“We took regular street skates apart and nailed the wheels to 1"x 6" planks. All the kids hung out there. After a while they wanted to build a hotel. The mayor said we can’t close that shop! That’s Boys’ Town!” Pat and Jack (in Supersuit) circa late ’70s. “I was doing hot-air balloon flights where I needed to survive water landings, so I sealed the ankles, wrists, and neck so it would hold air, installed a blow-up valve, and I could sleep all night afloat. It became the Navy’s official dive suit.” “Drew (Kampion) took this 1970s ad shot of me holding an original design that another company was claiming. Our headline said, ‘We did it first!’”

- 12. O’Neill also had to deal with surfing’s image problems at the time, particularly in the rowdy outpost that was Santa Cruz. “He was trying to become a legitimate Santa Cruz businessman,” says filmmaker Bruce Brown, who worked with O’Neill to promote his surf flicks throughout Northern California. “At the time everybody thought surfers were a bunch of scumbags. So he was trying to join the Rotary Club or whatever. When I’d come to visit, he’d always go, ‘Brown, just shut up. I’m trying to make a good impression here.’” O’Neill is Santa Cruz, and Santa Cruz is O’Neill. As I tag along with him for lunch in the Capitola area, he’s greeted by friendly faces and exuberant well-wishers everywhere we go. Most it seems have worked for him at one time or another, which they probably have. Everyone appears genuinely stoked to see him out and about. Perhaps no other single figure has shaped the town, even the greater coastal region of Northern California, more than he. In addition to providing the key to accessing the copious yet frigid surf of the greater Santa Cruz area, O’Neill set up a Pat and Jeff “Kookson” Gidden posing for a ’70s ad. Family O’Neill: Tim, Bridget, Jack, Pat, Cathi. Jack about to hit O’Neills, mid-’70s. At the helm of Marie Celine, a replica 60-foot coastal schooner, “She was a family boat and the prettiest for its size. We sailed it as far as Acapulco.” PHOTOS:O’NEILLCOLLECTION

- 13. traditional family-run business with high ethical and environ- mental standards. The values of the company are reflected within the community in which it operates, and vice versa. “Santa Cruz was the best move I ever made,” he says definitively. “It’s getting awfully crowded, but I still love it here. I’ve traveled a lot, and the climate here is perfect. The surf here is really good too, we’ve got so many surfing spots. It’s changed a lot, of course. It used to be a retirement town, but then the university moved in, and that changed things.” O’Neill, Inc., is also one of the very few American surf companies to thrive outside of the Southern California surf cartel, both in location and mindset. This is an important distinction, for it’s allowed the business, from its earliest days up through the present, to remain innovative and stay largely focused on functional surf design as opposed to fashion. The company has also helped give rise to a thriving local surf industry, arguably the densest population of surf shops and shapers in the world today. There are at least 15 retail surf shops within the roughly five square miles that make up the Santa Cruz area, along with dozens of independent shapers (M-10, Ward Coffey, Haut, Goin’, etc.), wetsuit manufacturers (O’Neill and Hotline), board manufacturers (Surftech), numerous surf schools, and practically any other surf product manufacturer you can imagine. For a region that’s not known as being a surf industry hub, it houses a surprising number of surfing- related businesses. As I watch various people’s reactions to O’Neill on the street, I wonder what it would be like to be the literal and figurative surfing icon that he’s become. He has always been to me as much a cartoon character as a living, breathing figure. Such is the power of marketing, and basing the image of an entire company on a one-eyed, swashbuckling figure. And that beard, that beard. From the ’70s to present, it has become synonymous not only with O’Neill wetsuits, but with burly, cold-water surfing from Northern California to the United Kingdom. “Jack O’Neill is one of the most recognizable faces in the world,” says Dennis Judson. “You go to the beach and everybody knows the guy. It’s funny, I helped develop the symbol with him in the eye patch, and we put it on everything. You put that graphic anywhere in the world now, and people know who it is.” “No one saves us but ourselves. No one can and no one may. We ourselves must walk the path.” —Gautama Buddha O’Neill is a kid at heart, and his youthful energy and natural curiosity has been at the core of both his business and personal success. Given this childlike nature, perhaps it’s fitting that he’s come full circle to found the nonprofit O’Neill Sea Odyssey. The program, now in its eleventh year, takes fourth through sixth graders for a cruise in Monterey Bay waters on the O’Neill catamaran, schooling them on ocean education. The organization has become his focus and passion, having handed over the reigns of the for-profit O’Neill enterprise to his children many years ago, and he speaks about it with great pride. “It’s such an advantage to have the kids out on the boat,” he says. “We teach them that the ocean is alive, and you’ve got to take care of it; that over half of the world’s oxygen comes from the ocean, and without a living ocean, we probably couldn’t make it. This is a message that they take home and tell their parents, and I think it’s something that will go on for generations.” To date the nonprofit has educated over 32,000 children on the ocean environment since its inception in 1996. And effective? One only need witness the classes in action, with dozens of attention- deficit-challenged school kids completely engaged for several hours at a time. Says O’Neill excitedly, “One time a little girl actually stood up in class and said, ‘Today is the happiest day of my life!’” This is how Jack O’Neill connects the ride, giving back to the ocean that has given him so much. As for his seemingly unassailable status, perhaps deep down we see him living our own dream, and for that reason we’re careful not to tarnish it, and in turn the man himself. In our minds, he’s lived the perfect life, and nobody wants to be the one to spoil the collective fantasy. Damn it if he wasn’t able to buck the system and do things his way, on his own terms, and find success in both the business and surfing worlds—playing in the ocean, mocking convention along the way. Indeed, “following his bliss,” to quote Joseph Campbell (and a former O’Neill marketing slogan). Says Joel Woods, “I was 14 when I went to work for him, and he gave a kid a job. That’s the legacy that he fostered —bring the kids up, get them out there, and expose them to the sea.” Who wouldn’t want to root for a character like that? 48 With Chinese drum, “I like the sound. I beat on it from time to time.” (opposite) 1957 Jaguar XK140, “Such a pleasure to be with.”

- 15. The Surfer’s Journal PDF Archives Copyright The Surfer’s Journal 2015 All rights reserved The use of this PDF is strictly for personal use and enjoyment. If you are interested in purchasing the right to reprint this article, you can do one at a time directly from our website www.surfersjournal.com or in large quantities by calling The Surfer’s Journal at 949-361-0331. You can also email us at customerservice@surfersjournal.com. Thanks, and enjoy!