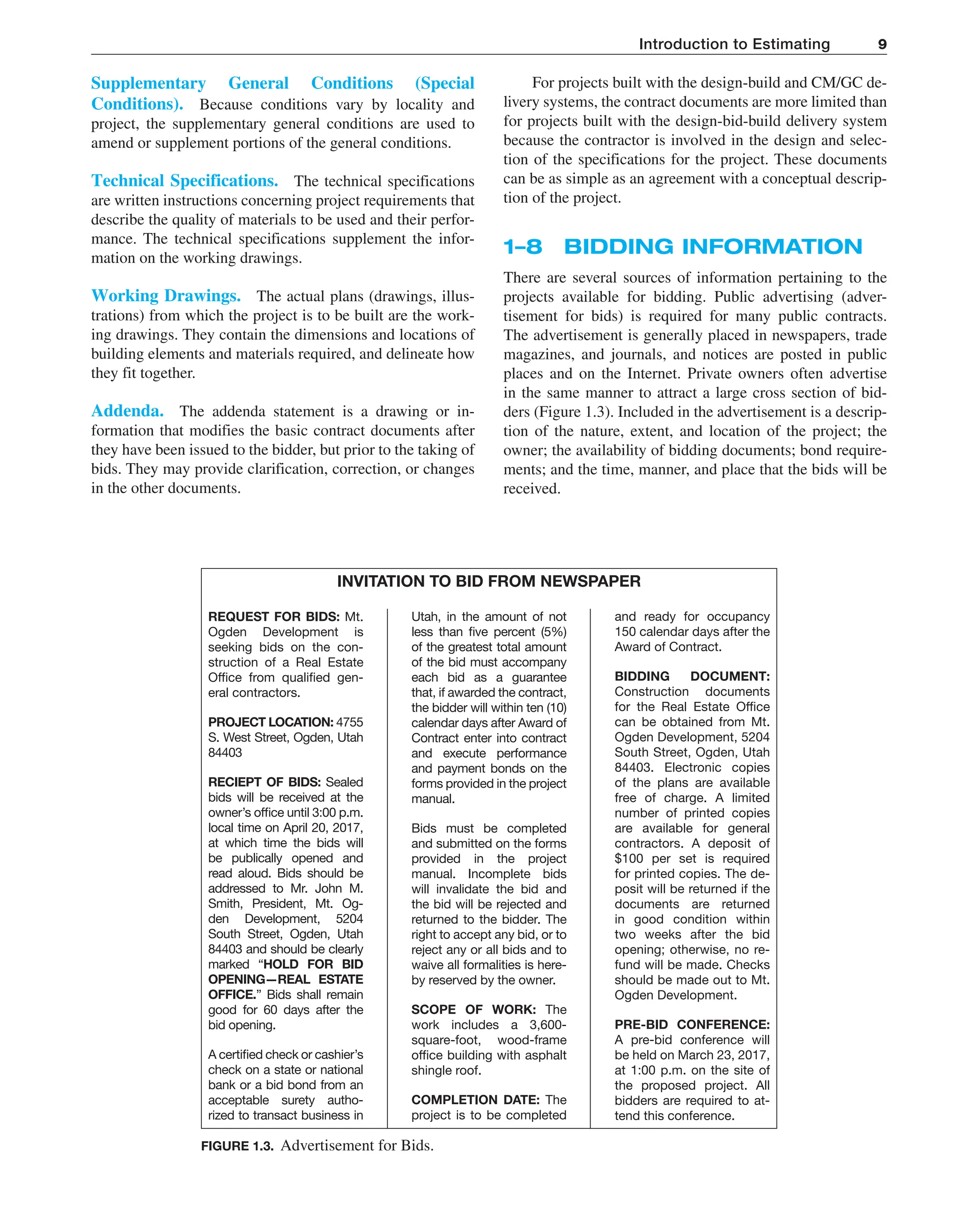

The document provides a comprehensive overview of construction estimating, detailing how estimators determine probable construction costs by analyzing project documents and various influencing factors. It discusses the importance of accurate estimates for competitive bidding and outlines different estimating methods, including detailed estimates, assembly estimating, square-foot estimates, and parametric estimates, each with specific applications and requirements. The text emphasizes the necessity for thoroughness in quantifying materials and costs, integrating direct and indirect expenses, and maintaining communication with subcontractors to ensure a complete and competitive bid.