Information Theory Coding Theorems For Discrete Memoryless Systems 2nd Edition Imre Csiszr

Information Theory Coding Theorems For Discrete Memoryless Systems 2nd Edition Imre Csiszr

Information Theory Coding Theorems For Discrete Memoryless Systems 2nd Edition Imre Csiszr

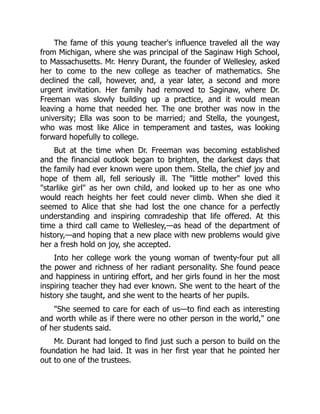

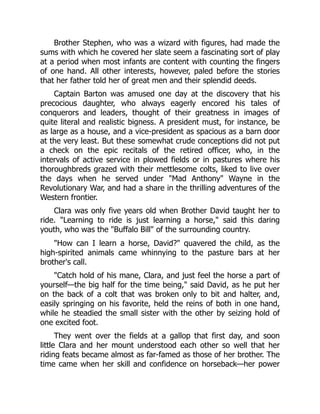

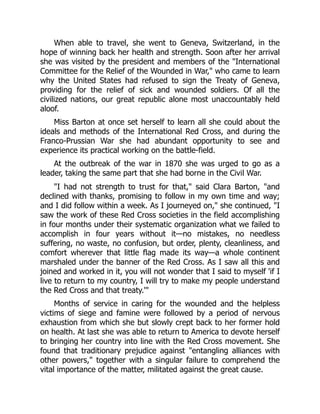

![Notation xiii

W : X → Y

W = {W(y|x) :

x ∈ X, y ∈ Y}

⎫

⎬

⎭

stochastic matrix with rows indexed by elements of X and

columns indexed by elements of Y; i.e., W(·|x) is a PD on

Y for every x ∈ X

W(B|x) probability of the set B ⊂ Y for the PD W(·|x)

Wn : Xn → Yn nth direct power of W, i.e., Wn(y|x)

n

i=1 W(yi |xi )

RV abbreviation for “random variable”

X, Y, Z RVs ranging over finite sets

Xn = (X1, . . . , Xn)

Xn = X1 . . . Xn

alternative notations for the vector-valued RV with compo-

nents X1, . . ., Xn

Pr {X ∈ A} probability of the event that the RV X takes a value in the

set A

PX distribution of the RV X, defined by PX (x) Pr {X = x}

PY|X=x conditional distribution of Y given X = x, i.e.,

PY|X=x (y) Pr {Y = y|X = x}; not defined if PX (x) = 0

PY|X the stochastic matrix with rows PY|X=x , called the con-

ditional distribution of Y given X; here x ranges over the

support of PX

PY|X = W means that PY|X=x = W(·|x) if PX (x) 0, involving no

assumption on the remaining rows of W

E X expectation of the real-valued RV X

var(X) variance of the real-valued RV X

X o

— Y o

— Z means that these RVs form a Markov chain in this order

(a, b), [a, b], [a, b) open, closed resp. left-closed interval with endpoints a b

|r|+ positive part of the real number r, i.e., |r|+ max (r, 0)

r largest integer not exceeding r

r smallest integer not less than r

min[a, b], max[a, b] the smaller resp. larger of the numbers a and b

r s means for vectors r = (r1, . . . ,rn), s = (s1, . . . , sn) of the

n-dimensional Euclidean space that ri si , i = 1, . . . , n

A convex closure of a subset A of a Euclidean space, i.e., the

smallest closed convex set containing A

exp, log are understood to the base 2

ln natural logarithm

a log(a/b) equals zero if a = 0 and +∞ if a b = 0

h(r) the binary entropy function

h(r) −r log r − (1 − r) log(1 − r), r ∈ [0, 1]

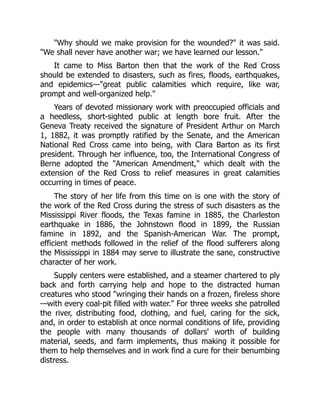

Most asymptotic results in this book are established with uniform convergence. Our

way of specifying the extent of uniformity is to indicate in the statement of results all

those parameters involved in the problem upon which threshold indices depend. In this

context, e.g., n0 = n0(|X|, ε, δ) means some threshold index which could be explicitly

given as a function of |X|, ε, δ alone.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-19-320.jpg)

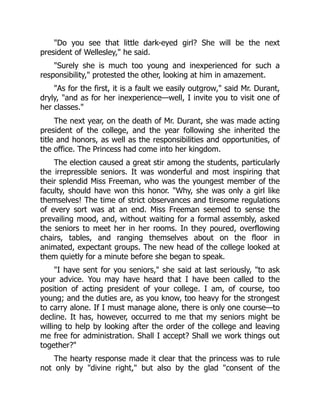

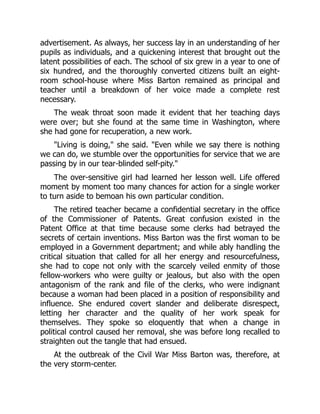

![6 Information measures in simple coding problems

This means that for the set

B(k, δ

)

x : x ∈ Xk

, Ek − δ

1

k

log

M(x)

PXk (x)

Ek + δ

we have

PXk (B(k, δ

)) 1 − ηk, where ηk

1

kδ2

max

i

var (Yi ).

Since by the definition of B(k, δ)

M(B(k, δ

)) =

x∈B(k,δ)

M(x)

x∈B(k,δ)

PXk (x) exp[k(Ek + δ

)] exp[k(Ek + δ

)],

it follows that

1

k

log s(k, ε)

1

k

log M(B(k, δ

)) Ek + δ

if ηk ε.

On the other hand, we have PXk (A ∩ B(k, δ)) 1 − ε − ηk for any set A ⊂ Xk with

PXk (A) 1 − ε. Thus for every such A, again by the definition of B(k, δ),

M(A) M(A ∩ B(k, δ

))

x∈A∩B(k,δ)

PXk (x) exp{k(Ek − δ

)}

(1 − ε − ηk) exp[(Ek − δ

)],

implying

1

k

log s(k, ε)

1

k

log(1 − ε − ηk) + Ek + δ

.

Setting δ δ/2, these results imply (1.6) provided that

ηk =

4

kδ2

max

i

var (Yi ) ε and

1

k

log(1 − ε − ηk) −

δ

2

.

By the assumption | log Mi (x)| c, the last relations hold if k k0(|X|, c, ε, δ).

An important corollary of Theorem 1.2 relates to testing statistical hypotheses. Sup-

pose that a probability distribution of interest for the statistician is given by either

P = {P(x) : x ∈ X} or Q = {Q(x) : x ∈ X}. She or he has to decide between P and

Q on the basis of a sample of size k, i.e., the result of k independent drawings from

the unknown distribution. A (non-randomized) test is characterized by a set A ⊂ Xk, in

➞ 1.3

the sense that if the sample X1 . . . Xk belongs to A, the statistician accepts P and else

accepts Q. In most practical situations of this kind, the role of the two hypotheses is not

symmetric. It is customary to prescribe a bound ε for the tolerated probability of wrong

decision if P is the true distribution. Then the task is to minimize the probability of a

wrong decision if hypothesis Q is true. The latter minimum is

➞ 1.4

β(k, ε) min

A⊂Xk

Pk(A)1−ε

Qk

(A).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-34-320.jpg)

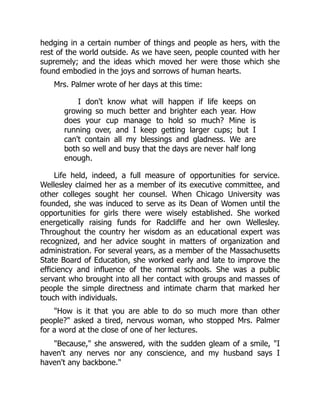

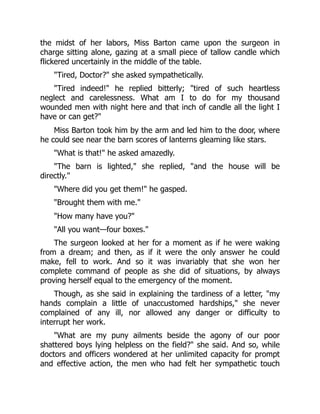

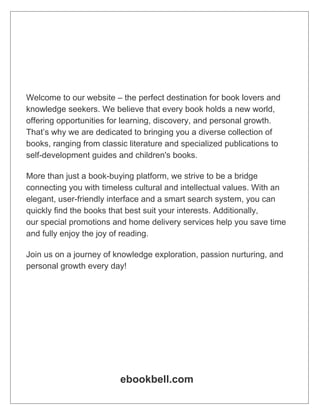

![Source coding and hypothesis testing 13

1.11. Show that if {Hm} is recursive, normalized and H2(p, 1 − p) is a continu-

ous function of p then (∗) holds. (See Faddeev (1956); the first “axiomatic”

characterization of entropy, using somewhat stronger postulates, was given by

Shannon (1948).)

Hint The key step is to prove Hm

1

m , . . . , 1

m

= log m. To this end,

check that f (m) Hm

1

m , . . . , 1

m

is additive, i.e., f (mn) = f (m) + f (n),

and that f (m + 1) − f (m) → 0 as m → ∞. Show that these properties and

f (2) = 1 imply f (m) = log m. (The last implication is a result of Erdös

(1946); for a simple proof, see Rényi (1961).)

1.12.∗ (a) Show that if Hm(p1, . . . , pm) =

m

i=1 g(pi ) with a continuous function

g(p), and {Hm} is additive and normalized, then (∗) holds. (Chaundy and

McLeod (1960)).

(b) Show that if {Hm} is expansible and branching then Hm(p1, . . . , pm) =

m

i=1 g(pi ), with g(0) = 0 (Ng, (1974).)

1.13.∗ (a) Show that if {Hm} is expansible, additive, subadditive, normalized and

H2(p, 1 − p) → 0 as p → 0 then (∗) holds.

(b) If {Hm} is expansible, additive and subadditive, show that there exist

constants A 0, B 0 such that

Hm(p1, . . . , pm) = A

−

m

i=1

pi log pi

+ B log |{i : pi 0}|.

(Forte (1975), Aczél–Forte–Ng (1974).)

1.14.∗ Suppose that Hm(p1, . . . , pm) = − log −1

m

i=1 pi (pi )

with some

strictly monotonic continuous function on (0,1] such that t(t) →

0(0) 0 as t → 0. Show that if {Hm} is additive and normalized then

either (∗) holds or

Hm(p1, . . . , pm) =

1

1 − α

log

m

i=1

pα

i with some α 0, α = 1.

(Conjectured by Rényi (1961) and proved by Daróczy (1964). The preceding

expression is called Rényi’s entropy of order α. A similar expression was used

earlier by Schützenberger (1954) as “pseudo information.”)

1.15. For P = (p1, . . . , pm), denote by Hα(P) the Rényi entropy of order α if

α = 1, α 0, and the Shannon entropy H(P) if α = 1. Show that Hα(P)

is a continuous, non-increasing function of α, whose limits as α → 0, resp.

α → +∞, are

H0(P) log |{i : pi 0}| , H∞(P) min (− log pi ),

called the maxentropy, resp. minentropy, of P.

Hint Check that log

m

i=1 pα

i is a convex function of α.

1.16. (Fisher’s information) Let {Pϑ } be a family of distributions on a finite set X,

where ϑ is a real parameter ranging over an open interval. Suppose that the

probabilities Pϑ (x) are positive and that they are continuously differentiable

functions of ϑ. Write](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-41-320.jpg)

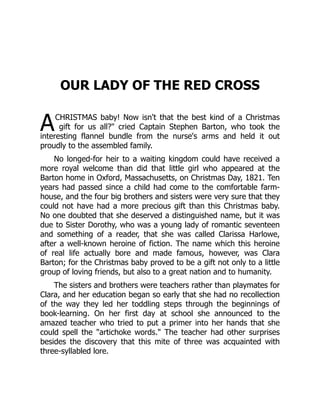

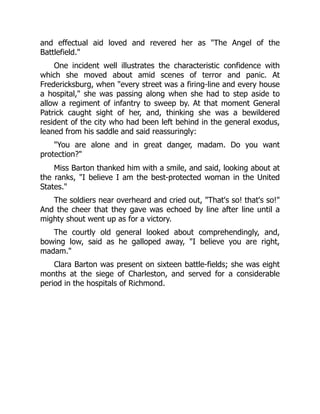

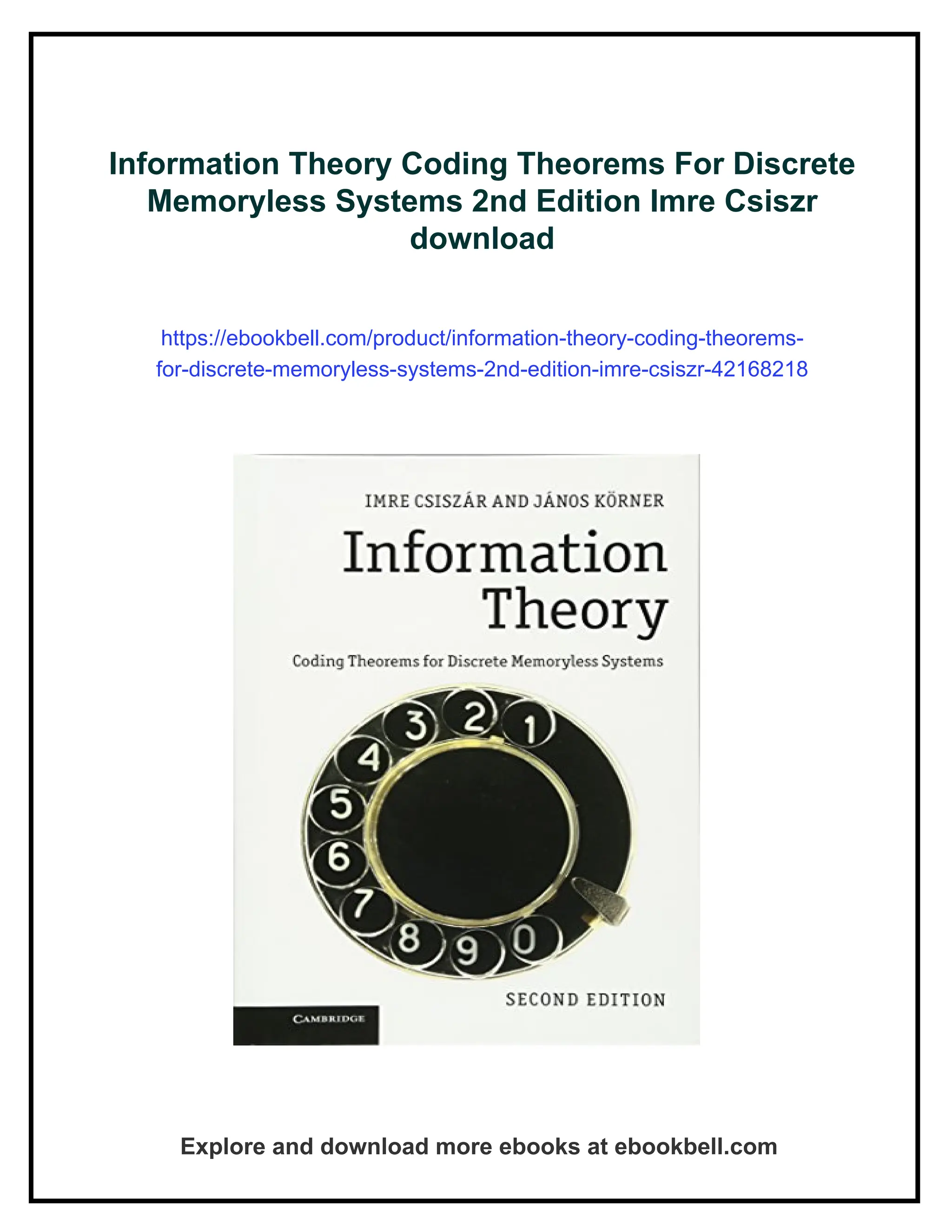

![Types and typical sequences 17

LEMMA 2.3 For any type P of sequences in Xk

➞ 2.2

(k + 1)−|X|

exp[kH(P)] |TP| exp[kH(P)].

Proof Since (2.1) implies

Pk

(x) = exp[−kH(P)] if x ∈ TP

we have

|TP| = Pk

(TP) exp[kH(P)].

Hence it is enough to prove that

Pk

(TP) (k + 1)−|X|

.

This will follow by the Type counting lemma if we show that the Pk-probability of T

P

is maximized for

P = P.

By (2.1) we have

Pk

(T

P) = |T

P| ·

a∈X

P(a)k

P(a)

=

k!

a∈X

(k

P(a))! a∈X

P(a)k

P(a)

for every type

P of sequences in Xk.

It follows that

Pk(T

P)

Pk(TP)

=

a∈X

(kP(a))!

(k

P(a))!

P(a)k(

P(a)−P(a))

.

Applying the obvious inequality n!

m! nn−m, this gives

Pk(T

P)

Pk(TP)

a∈X

kk(P(a)−

P(a))

= 1.

If X and Y are two finite sets, the joint type of a pair of sequences x ∈ Xk and y ∈ Yk

is defined as the type of the sequence {(xi , yi )}k

i=1 ∈ (X × Y)k. In other words, it is the

distribution Px,y on X × Y defined by

Px,y(a, b)

1

k

N(a, b|x, y) for every a ∈ X, b ∈ Y.

Joint types will often be given in terms of the type of x and a stochastic matrix V : X → Y

such that

Px,y(a, b) = Px(a)V (b|a) for every a ∈ X, b ∈ Y. (2.2)

Note that the joint type Px,y uniquely determines V (b|a) for those a ∈ X which do

occur in the sequence x. For conditional probabilities of sequences y ∈ Yk, given a

sequence x ∈ Yk, the matrix V of (2.2) will play the same role as the type of y does for

unconditional probabilities.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-45-320.jpg)

![18 Information measures in simple coding problems

DEFINITION 2.4 We say that y ∈ Yk has conditional type V given x ∈ Xk if

N(a, b|x, y) = N(a|x)V (b|a) for every a ∈ X, b ∈ Y.

For any given x ∈ Yk and stochastic matrix V : X → Y, the set of sequences y ∈ Yk

having conditional type V given x will be called the V-shell of x, denoted by Tk

V (x) or

simply TV (x).

REMARK The conditional type of y given x is not uniquely determined if some a ∈ X

do not occur in x. Still, the set TV (x) containing y is unique.

Note that conditional type is a generalization of types. In fact, if all the components of

➞ 2.3

the sequence x are equal (say x) then the V -shell of x coincides with the set of sequences

of type V (·|x) in Yk.

In order to formulate the basic size and probability estimates for V -shells, it will be

convenient to introduce some notations. The average of the entropies of the rows of a

stochastic matrix V : X → Y with respect to a distribution P on X will be denoted by

H(V |P)

=

x∈X

P(x)H(V (·|x)). (2.3)

The analogous average of the informational divergences of the corresponding rows of

two stochastic matrices V : X → Y and W : X → Y will be denoted by

D(V W|P)

=

x∈X

P(x)D(V (·|x)W(·|x)). (2.4)

Note that H(V |P) is the conditional entropy H(Y|X) of RVs X and Y such that X has

distribution P and Y has conditional distribution V given X. The quantity D(V W|P)

is called the conditional informational divergence. A counterpart of Lemma 2.3 for

V -shells is

LEMMA 2.5 For every x ∈ Xk and stochastic matrix V : X → Y such that TV (x) is

non-void, we have

(k + 1)−|X||Y|

exp [kH(V |Px)] |TV (x)| exp [kH(V |Px)].

Proof This is an easy consequence of Lemma 2.2. In fact, |TV (x)| depends on x only

through the type of x. Hence we may assume that x is the juxtaposition of sequences

xa, a ∈ X, where xa consists of N(a|x) identical elements a. In this case TV (x) is the

Cartesian product of the sets of sequences of type V (·|a) in YN(a|x), with a running over

those elements of X which occur in x.

Thus Lemma 2.3 gives

a∈X

(N(a|x) + 1)−|Y|

exp [N(a|x)H(V (·|a))]

|TV (x)|

a∈X

exp [N(a|x)H(V (·|a))],

whence the assertion follows by (2.3).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-46-320.jpg)

![Types and typical sequences 19

LEMMA 2.6 For every type P of sequences in Xk and distribution Q on X

Qk

(x) = exp [−k(D(PQ) + H(P))] if x ∈ TP, (2.5)

(k + 1)−|X|

exp [−kD(PQ)] Qk

(TP) exp [−kD(PQ)]. (2.6)

Similarly, for every x ∈ Xk and stochastic matrices V : X → Y, W : X → Y such that

TV (x) is non-void,

Wk

(y|x) = exp [−k(D(V W|Px) + H(V |Px))] if y ∈ TV (x), (2.7)

(k + 1)−|XY|

exp [−kD(V W|Px)] Wk

(TV (x)|x)

exp [−kD(V W|Px)]. (2.8)

Proof Equation (2.5) is just a rewriting of (2.1). Similarly, (2.7) is a rewriting of the

identity

Wk

(y|x) =

a∈X, b∈Y

W(b|a)N(a,b|x,y)

.

The remaining assertions now follow from Lemmas 2.3 and 2.5.

The quantity D(PQ) + H(P) = −

x∈X P(x) log Q(x) appearing in (2.5) is

sometimes called inaccuracy.

For Q = P, the Qk-probability of the set Tk

P is exponentially small (for large k);

cf. Lemma 2.6. It can be seen that even Pk(Tk

P) → 0 as k → ∞. Thus sets of large ➞ 2.2

probability must contain sequences of different types. Dealing with such sets, the con-

tinuity of the entropy function plays a relevant role. The next lemma gives more precise

information on this continuity.

The variation distance of two distributions P and Q on X is

d(P, Q)

x∈X

|P(x) − Q(x)|.

(Some authors use the term for the half of this.)

LEMMA 2.7 If d(P, Q) = 1/2 then

|H(P) − H(Q)| − log

|X|

.

For a sharpening of this lemma, see Problem 3.10.

Proof Write ϑ(x) |P(x) − Q(x)|. Since f (t) −t log t is concave and f (0) =

f (1) = 0, we have for every 0 t 1 − τ, 0 τ 1/2,

| f (t) − f (t + τ)| max( f (τ), f (1 − τ)) = −τ log τ.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-47-320.jpg)

![20 Information measures in simple coding problems

Hence for 0 1/2

|H(P) − H(Q)|

x∈X

| f (P(x)) − f (Q(x))| −

x∈X

ϑ(x) log ϑ(x)

=

−

x∈X

ϑ(x)

log

ϑ(x)

− log

log |X| − log ,

where the last step follows from Corollary 1.1.

DEFINITION 2.8 For any distribution P on X, a sequence x ∈ Xk is called P-typical

with constant δ if

1

k

N(a|x) − P(a) δ for every a ∈ X

and, in addition, no a ∈ X with P(a) = 0 occurs in x. The set of such sequences will be

denoted by Tk

[P]δ

or simply T[P]δ . If X is a RV with values in X, we refer to PX -typical

sequences as X-typical, and write Tk

[X]δ

or T[X]δ for Tk

[PX ]δ

.

REMARK Tk

[P]δ

is the union of the sets Tk

P

for those types

P of sequences in Xk which

satisfy

|

P(a) − P(a)| δ for every a ∈ X

and

P(a) = 0 whenever P(a) = 0.

DEFINITION 2.9 For a stochastic matrix W : X → Y, a sequence y ∈ Yk is W-typical

under the condition x ∈ Xk (or W-generated by the sequence x ∈ Xk) with constant δ if

1

k

N(a, b|x, y) −

1

k

N(a|x)W(b|a) δ for every a ∈ X, b ∈ Y,

and, in addition, N(a, b|x, y) = 0 whenever W(b|a) = 0. The set of such sequences

y will be denoted by Tk

[W]δ

(x) or simply by T[W]δ (x). Further, if X and Y are RVs

with values in X resp. Y and PY|X = W, then we shall speak of Y|X-typical or

Y|X-generated sequences and write Tk

[Y|X]δ

(x) or T[Y|X]δ (x) for Tk

[W]δ

(x).

Sequences Y|X-generated by an x ∈ Xk are defined only if the condition PY|X = W

uniquely determines W(·|a) for a ∈ X with N(a|x) 0, that is, if no a ∈ X with

PX (a) = 0 occurs in the sequence x; this automatically holds if x is X-typical.

The set Tk

[XY]δ

of (X, Y)-typical pairs (x, y) ∈ Xk × Yk is defined applying

Definition 2.8 to (X, Y) in the role of X. When the pair (x, y) is typical, we say that

x and y are jointly typical.

LEMMA 2.10 If x ∈ Tk

[X]δ

and y ∈ Tk

[Y|X]δ

(x) then (x, y) ∈ Tk

[XY]δ+δ

and, conse-

quently, y ∈ Tk

[Y]δ

for δ (δ + δ)|X|.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-48-320.jpg)

![Types and typical sequences 21

For reasons which will be obvious from Lemmas 2.12 and 2.13, typical sequences ➞ 2.4

will be used with δ depending on k such that

δk → 0,

√

k · δk → ∞ as k → ∞. (2.9)

Throughout this book, we adopt the following convention.

CONVENTION 2.11 (Delta-convention) To every set X resp. ordered pair of sets (X, Y)

there is given a sequence {δk}∞

k=1 satisfying (2.9). Typical sequences are understood with

these δk. The sequences {δk} are considered as fixed, and in all assertions dependence

on them will be suppressed. Accordingly, the constant δ will be omitted from the nota-

tion, i.e., we shall write Tk

[P], Tk

[W](x), etc. In most applications, some simple relations

between these sequences {δk} will also be needed. In particular, whenever we need that

typical sequences should generate typical ones, we assume that the corresponding δk are

chosen according to Lemma 2.10.

LEMMA 2.12 There exists a sequence εk → 0 depending only on |X| and |Y| (see

the delta-convention) so that for every distribution P on X and stochastic matrix

W : X → Y

Pk

(Tk

[P]) 1 − εk,

Wk

(Tk

[W](x)|x) 1 − εk for every x ∈ Xk

.

REMARK More explicitly,

Pk

(Tk

[P]δ

) 1 −

|X|

4kδ2

, Wk

(Tk

[W]δ

(x)|x) 1 −

|XY|

4kδ2

,

for every δ 0, and here the terms subtracted from 1 could be replaced even by

2|X|e−2kδ2

resp. 2|X||Y|e−2kδ2

.

Proof It suffices to prove the inequalities of the Remark. Clearly, the second inequality

implies the first one as a special case (choose in the second inequality a one-point set

for X). Now if x = x1 . . . xk, let Y1, Y2, . . ., Yk be independent RVs with distributions

PYi = W(·|xi ). Then the RV N(a, b|x, Yk) has binominal distribution with expectation

N(a|x)W(b|a) and variance

N(a|x)W(b|a)(1 − W(b|a))

1

4

N(a|x)

k

4

.

Thus by Chebyshev’s inequality

Pr {|N(a, b|x, Yk

) − N(a|x)W(b|a)| kδ}

1

4kδ2

for every a ∈ X, b ∈ Y. Hence the inequality with 1 − |XY|

4kδ2 follows. The claimed

sharper bound is obtained similarly, employing Hoeffding’s inequality (see Problem

3.18 (b)) instead of Chebyshev’s.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-49-320.jpg)

![22 Information measures in simple coding problems

LEMMA 2.13 There exists a sequence εk → 0 depending only on |X| and |Y| (see

the delta-convention) so that for every distribution P on X and stochastic matrix

W : X → Y

1

k

log |Tk

[P]| − H(P) εk

and

1

k

log |Tk

[W](x)| − H(W|P) εk for every x ∈ Tk

[P].

Proof The first assertion immediately follows from Lemma 2.3 and the uniform con-

tinuity of the entropy function (Lemma 2.7). The second assertion, containing the first

one as a special case, follows similarly from Lemmas 2.5 and 2.7. To be formal, observe

that, by the type counting lemma, Tk

[W](x) is the union of at most (k + 1)|XY| disjoint

V -shells TV (x). By Definitions 2.4 and 2.9, all the underlying V satisfy

|Px(a)V (b|a) − Px(a)W(b|a)| δ

k for every a ∈ X, b ∈ Y, (2.10)

where {δ

k} is the sequence corresponding to the pair of sets X, Y by the delta-convention.

By (2.10) and Lemma 2.7, the entropies of the joint distributions on X × Y determined

by Px and V resp. by Px and W differ by at most −|XY|δ

k log δ

k (if |XY|δ

k 1/2)

and thus also

|H(V |Px) − H(W|Px)| −|XY|δ

k log δ

k.

On account of Lemma 2.5, it follows that

(k + 1)−|XY|

exp [k(H(W|Px) + |XY|δ

k log δ

k)]

|Tk

[W](x)| (k + 1)|XY|

exp [k(H(W|Px) − |XY|δ

k log δ

k)]. (2.11)

Finally, since x is P-typical, i.e.,

|Px(a) − P(a)| δk for every a ∈ X,

we have by Corollary 1.1

|H(W|Px) − H(W|P)| δklog|Y|.

Substituting this into (2.11), the assertion follows.

The last basic lemma of this chapter asserts that no “large probability set” can be

substantially smaller than T[P] resp.T[W](x).

LEMMA 2.14 Given 0 η 1, there exists a sequence εk → 0 depending only on

η, |X| and |Y| such that

(i) if A ⊂ Xk, Pk(A) η then 1

k log|A| H(P) − εk;

(ii) if B ⊂ Yk, Wk(B|x) η then 1

k log|B| H(W|Px) − εk.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-50-320.jpg)

![Types and typical sequences 23

COROLLARY 2.14 There exists a sequence ε

k → 0 depending only on η, |X|, |Y| (see

the delta-convention) such that if B ⊂ Yk and Wk(B|x) η for some x ∈ T[P] then

1

k

log|B| H(W|P) − ε

k.

Proof It is sufficient to prove (ii). By Lemma 2.12, the condition Wk(B|x) η

implies

Wk

(B ∩ T[W](x)|x)

η

2

for k k0(η, |X|, |Y|). Recall that T[W](x) is the union of disjoint V -shells TV(x) satis-

fying (2.10); see the proof of Lemma 2.13. Since Wk(y|x) is constant within a V -shell

of x, it follows that

|B ∩ TV (x)|

η

2

|TV (x)|

for at least one V : X → Y satisfying (2.10). Now the proof can be completed using

Lemmas 2.5 and 2.7 just as in the proof of the previous lemma.

Observe that the preceding three lemmas contain a proof of Theorem 1.1. Namely, ➞ 2.5

the fact that about kH(P) binary digits are sufficient for encoding k-length messages

of a DMS with generic distribution P, is a consequence of Lemmas 2.12 and 2.13,

while the necessity of this many binary digits follows from Lemma 2.14. Most coding

theorems in this book will be proved using typical sequences in a similar manner. The

merging of several nearby types has the advantage of facilitating computations. When

dealing with the more refined questions of the speed of convergence of error proba-

bilities, however, the method of typical sequences will become inappropriate. In such

problems, we shall have to consider each type separately, relying on the first part of this

chapter. Although this will not occur until Chapter 9, as an immediate illustration of the

more subtle method we now refine the basic source coding result, Theorem 1.1.

THEOREM 2.15 For any finite set X and R 0 there exists a sequence of k-to-nk

binary block codes ( fk, ϕk) with

nk

k

→ R

such that for every DMS with alphabet X and arbitrary generic distribution P, the

probability of error satisfies

e( fk, ϕk) exp

−k

inf

Q:H(Q)R

D(Q||P) − ηk

(2.12)

with

ηk

log(k + 1)

k

|X|.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-51-320.jpg)

![24 Information measures in simple coding problems

This result is asymptotically sharp for every particular DMS, in the sense that for any

sequence of k-to-nk binary block codes, nk/k → R implies

lim

k→∞

1

k

log e( fk, ϕk) − inf

Q:H(Q)R

D(Q||P). (2.13)

The infimum in (2.12) and (2.13) is finite iff R log s(P), and then it equals the

minimum subject to H(Q) R.

Here s(P) denotes the size of the support of P, that is, the number of those a ∈ X for

which P(a) 0.

REMARK This result sharpens Theorem 1.1 in two ways. First, for a DMS with

generic distribution P, and R H(P), it gives the precise asymptotics, in the expo-

nential sense, of the probability of error of the best codes with nk/k → R (the result

is also true, but uninteresting, for R H(P)). Second, it shows that this optimal per-

formance can be achieved by codes not depending on the generic distribution of the

source. The remaining assertion of Theorem 1.1, namely that for nk/k → R H(P)

the probability of error tends to 1, can be sharpened similarly.

➞ 2.6

Proof of Theorem 2.15. Write

Ak

Q:H(Q)R

TQ.

Then, by Lemmas 2.2 and 2.3,

|Ak| (k + 1)|X|

exp(kR); (2.14)

further, by Lemmas 2.2 and 2.6,

Pk

(Xk

− Ak) (k + 1)|X|

exp

− k min

Q:H(Q)R

D(Q||P)

. (2.15)

Let us encode the sequences in Ak in a one-to-one way and all others by a fixed

codeword, say. Equation (2.14) shows that this can be done with binary codewords of

length nk satisfying nk/k → R. For the resulting code, (2.15) gives (2.12), with

ηk

log(k + 1)

k

|X|.

The last assertion of Theorem 2.15 is obvious, and implies that it suffices to prove

(2.13) for R log s(P). The number of sequences in Xk correctly reproduced by a

k-to-nk binary block code is at most 2nk . Thus, by Lemma 2.3, for every type Q of

sequences in Xk satisfying

(k + 1)−|X|

exp [kH(Q)] 2nk+1

, (2.16)

at least half of the sequences in TQ will not be reproduced correctly. On account of

Lemma 2.6, it follows that

e( fk, ϕk)

1

2

(k + 1)−|X|

exp [−kD(Q||P)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-52-320.jpg)

![26 Information measures in simple coding problems

2.2. Prove that the size of Tk

P is of order of magnitude k−(s(P)−1)/2 exp{kH(P)},

where s(P) is the number of elements a ∈ X with P(a) 0. More precisely,

show that

log |Tk

P| = kH(P) −

s(P) − 1

2

log (2πk) −

1

2

a:P(a)0

logP(a) −

ϑ(k, P)

12 ln 2

s(P),

where 0 ϑ(k, P) 1.

Hint Use Robbins’ sharpening of Stirling’s formula:

√

2πnn+ 1

2 e−n+ 1

12(n+1) n!

√

2πnn+ 1

2 e−n+ 1

12n

(see e.g. Feller (1968), p. 54), noting that P(a) 1/k whenever P(a) 0.

2.3. Clearly, every y ∈ Yk in the V -shell of an x ∈ Xk has the same type Q where

Q(b)

a∈X

Px(a)V (b|a).

(a) Show that TV(x) = TQ even if all the rows of the matrix V are equal to Q

(unless x consists of identical elements).

(b) Show that if Px = P then

(k + 1)−|X||Y|

exp [−kI (P, V )]

|TV (x)|

|TQ|

(k + 1)|Y|

exp [−kI (P, V )],

where I (P, V ) H(Q) − H(V |P) is the mutual information of RVs X and

Y such that PX = P and PY|X = V . In particular, if all rows of V are equal

to Q then the size of TV(x) is not “exponentially smaller” than that of TQ.

2.4. Prove that the first resp. second condition of (2.9) is necessary for Lemmas 2.13

resp. 2.12 to hold.

2.5. (Entropy-typical sequences) Let us say that a sequence x ∈ Xk is entropy-P-

typical with constant δ if

−

1

k

log Pk

(x) − H(P) δ;

further, y ∈ Yk is entropy-W-typical under the condition x if

−

1

k

logWk

(y|x) − H(W|Px) δ.

(a) Check that entropy-typical sequences also satisfy the assertions of Lemmas

2.12 and 2.13 (if δ = δk is chosen as in the delta-convention).

Hint These properties were implicitly used in the proofs of Theorems 1.1

and 1.2.

(b) Show that typical sequences – with constants chosen according to the delta-

convention – are also entropy-typical, with some constants δ

k = cP · δk resp.

δ

k = cW · δk. On the other hand, entropy-typical sequences are not necessar-

ily typical with constants of the same order of magnitude.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21084109-250516113446-c798925c/85/Information-Theory-Coding-Theorems-For-Discrete-Memoryless-Systems-2nd-Edition-Imre-Csiszr-54-320.jpg)