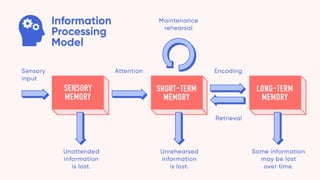

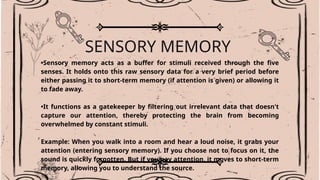

Information Processing Theory (IPT) is a cognitive approach that likens human mental processes to computer information processing, focusing on how the brain receives, processes, and stores information. Key components of the model include sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory, each with distinct characteristics and roles in information retention and retrieval. The theory also outlines pedagogical implications for teaching strategies to enhance student learning and memory retention.