This document is a dissertation submitted by Ibrahim Bhamji to Queen Mary University of London in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Science in Dental Public Health. The dissertation examines knowledge sharing in professional communities of practice among dentists regarding tobacco cessation interventions in NHS hospitals through qualitative interviews. It includes an introduction stating the problem, research question and objectives. A literature review covers topics like the prevalence and health impacts of tobacco use, and interventions for cessation. The methodology describes using a qualitative research design with interviews at NHS hospitals. Results are presented thematically regarding knowledge sharing and effective intervention elements. Discussion analyzes findings and limitations, and conclusions provide recommendations.

![21

Smokers who contacted helplines had higher quit rates to receive proactive

counselling service follow-up RR risk ratio 1.37 95%CI: 1.26 to 1.50. Quit line services

were effective and assisted the smokers with proactive tobacco counselling services

(Stead et al., 2015, Stead and Lancaster, 2015).

Clinical approach

The cessation service or advice, which could be provided in the health care setting

such as General Physician practices and dental practices, were effective in smoking

cessation services. There were several published studies which showed it is an

effective approach.

General Practice

One study presented the finding that little or plain advice from physicians had little

effect on smoking cessation but in contrast, brief cessation advice can achieve a

higher quitting rate(Stead et al., 2013). Another study with a new approach known

as ASK-ADVICE-CONNECT compared to the tradition 5 A’s approach (Ask, Advise,

Assess, Assist, Arrange) for smoking cessation treatment in health care setting,

showed the following findings; “in the AAC clinics, 7.8% of all identified smokers

involved in treatment vs. 0.6% in the AAR clinics (t4=9.19[p<. 001]; odds ratio, 11.60

[95% CI, 5.53-24.32], a 13-fold increase in the proportion of smokers who enrolled in

treatment. The system changes implemented in the AAC approach could be taken by

other health care systems and have tremendous potential to reduce tobacco related

mortality and morbidity” (Vidrine et al., 2013). One study from India on the

effectiveness of 5 A’s intervention to assess the agreement between patient and

physician was conducted. Agreement was measured by level of percentage (Low,

High, Medium) The results were that slight agreement was noticed between patient

and physician in regards to Ask and arrange component in contrast to Advise, Asses

and assist component, which low level agreement. Except advise, all other

components of 5A’s showed higher agreement for those who were made to quit

smoking (Panda et al., 2015).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-21-320.jpg)

![26

pleasure and entertainment from a systematic review conducted by Akl et al. Water

pipe smokers perceived, in contract to cigarettes, water pipe smoking was less

harmful, less addictive and more socially acceptable. Likewise, they were confident

in their ability to quit this (Akl et al., 2013).

Ahmady et al conducted the randomised controlled trial to know the attitudes of

patient towards dentists 5A’ approach between intervention group receiving chair

side counselling and control group receiving no intervention showed significantly

positive attitudes towards the dentists roles in advising smoking cessation compared

with control groups. 88.9% who were planning to quit smoking, 72.27% had agreed

that they discussed the ill effects of tobacco, 82% said dentists should offer

assistance and services aiding them to quit tobacco. The majority of the patients

were not aware of the resources available to them to aid them to quit. Dentists are

at the forefront to providing information to patients who need help in quitting the

use of tobacco (Ahmady et al., 2014). Interventions groups were given tobacco

counselling and control groups were given no counselling, and were compared it pre

and post test with and without intervention. The mean attitudes scored of

counselling groups, which were intervention compared to control groups

significantly higher post tobacco counselling [68.09(SD 13.5) VS 77.4(SD 15.4)]

(p=0.009).(Ahmady et al., 2014)

The findings from an Australian study revealed that most of the patients wanted

their dentists to be keen about their smoking status and discuss smoking with them

(Rikard-Bell et al., 2003).

Barriers and facilitators

Several studies were reviewed to know the barriers and facilitators for delivering

smoking cessation. The most common barrier in providing smoking cessation

intervention, reported in few of these studies, was lack of time. A study conducted

by Dalia et al to assess the management of patients who are smokers through post

questioners with specialist periodontics and dental hygienist. The findings presented

were barriers such as lack of time and poor response from patient which may inhibit

them to deliver smoking cessation advice (Dalia et al., 2007). A question-based](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-26-320.jpg)

![47

Section 2 - Knowledge sharing

Most of the interviewees had their experience of sharing their knowledge with their

peers, students, juniors and seniors as the interview questions were based

hypothetically by showing them some vignettes of some real life experiences of

dentists, which they encountered. Most of them had similar situations and

experience, as the scenarios in the vignettes, within their communities of practice.

“Okay yes I have had things like that. People coming to ask for advice

[Interviewee 3]

“Okay, So I see these groups of patients a lot through being a special care dentist”

[Interviewee 4]

“Ok. I’ve come across a not too dissimilar case to the number five that you’ve asked

me to read and that was similarly a colleague who had….”

[Interviewee 5]

“Ok, yeah I’ve come across situations like this before”

[Interviewee 6]

As you can see, most of the participants responded to having a past experience of

knowledge sharing. It seems to appear they mostly agree with the scenarios

presented and through this they have reported knowledge sharing experiences in

the past within the professional community of their practice within the hospital

setting.

Tacit and explicit knowledge interdepended

The participants, who are clinical academics, mostly shared their knowledge with

students, patients, peers, juniors, and seniors. The participating dentists asserted

that some knowledge couldn’t easily be learnt or adapted from a textbook, which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-47-320.jpg)

![48

could be termed as explicit knowledge and only learnt through practical

demonstrations.

Dentists felt even though they share explicit knowledge, which is written and verbal,

but they share with demonstration, and practically which is a tacit knowledge form.

Therefore with dentistry being involved in mostly practical work, the interviewees

through demonstrations and ‘tell-show-do’ methodology more often shared the

knowledge sharing use of tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge.

The interviewees mostly shared their knowledge with students, colleagues and

patients, as the participants were from the Royal London Hospital, which is a

university teaching hospital.

Interviewee 1 compares how effective tacit knowledge is compared to explicit

knowledge when referring to a skilled speciality. He uses the example below to

assert his belief that practical skills knowledge which can be shared or learned

effectively through demonstration.

“Yeah. We have ideas and techniques that we share. For example, in Endo because

you need to be very skilled at removing broken instruments so showing somebody

how to do this is part of the sharing of knowledge. Yeah, practical skills must be

shared in that way, you cannot easily learn it from a textbook.”

[Interviewee 1]

A similar finding was found from Interviewee 5, as below. The knowledge sharing

was of both explicit and tacit knowledge to, despite this, there was more emphasis

on tacit knowledge, which is practical sharing of knowledge through the tell-show-do

method.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-48-320.jpg)

![49

“It’s sort of show, tell, do so we discuss the principals behind we choose certain

stitches for the skin and certain stitches for inside the mouth and then we would do it

for them while they watch closely or perhaps we would do the first half and then they

would do the second half so it’s very hands on.”

[Interviewee 5]

Interviewee 3, in their capacity as a clinical lecturer, relies on tacit knowledge as this

can only be shared through a demonstration on the patient itself.

“Yeah actually. It is part of my role as a clinical lecturer. I do many demonstrations.

In the clinic when I supervise the students I may have to see their patients, explain in

the patients mouth itself to the student what, really in the diagnosis part.”

[Interviewee 3]

On the other hand, Interviewee 6 given as example of explicit knowledge which is

shared by giving them the provision of information which is written and

recommended.

“I think yes, not so much they’ve asked me whether they are taking the medicine

correctly. It’s normally the case that I ask them and they volunteer the information

how they’ve been taking the medication and they would normally tell me whether

they are talking it correctly or not and I would tell them if they had been doing it

correctly or not.”

[Interviewee 6]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-49-320.jpg)

![50

Sources of knowledge sharing

There are common findings to the sources of sharing knowledge which includes:

Emails

“I don’t know, following their emails, sometimes they ask for surveys or information

so I would try to participate in those.” [Interviewee 3]

Facebook

The source of knowledge is through Facebook social media, which is an online

community for knowledge sharing with specific dental networks.

“Yeah, so there is a Facebook forum that I regularly contribute to”. [Interviewee 1]

“Sharing their Facebook, well not their Facebook, their programs, they have Smile

Programs or things like that. I share them on Facebook so I think I do my job. But

that’s all.” [Interviewee 3]

Expert opinions

There is always an expert in one’s own field. There were findings, which showed that

dentists shares knowledge with expertise. It may be possibly that knowledge from

experts is more reasonable and trustworthy.

“From there I discussed with one of the consultants I was working for, if he was to

receive a referral, how he would like the case managed.” [Interviewee 5]

"You have the clinical expertise, I'll just go by what you say" [interviewee 4]

“If I’m not sure about something there are a lot of colleagues at the same level of

seniority and maybe higher level of expertise in the specific field that I can directly

approach them.” [Interviewee 2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-50-320.jpg)

![51

Knowledge seeking-acquisition

The other commonality in the study was knowledge acquisition seeking, where

dentists revealed they acquired or sought knowledge through peer discussion, case-

based learning and formal learning. Most of the dentists felt that acquiring

knowledge from their peers had a great impact on themselves. Whereas, case-based

learning seems to be very useful for them to seek/acquire knowledge as case-based

learning is where a dentist learns a general principle and applies this to a particular

case. Cases are like stories, which use metaphors to help convey tacit

understanding/knowledge with artefacts, which is similar to the above section of

tacit ‘know how’. The other behaviour of dentists for knowledge seeking-acquisition

was through formal learning. A dentist working in a hospital and seeking-acquiring

knowledge regularly reads journals, participates in conferences and watches

presentations.

Peer discussion

“Yeah, I've learnt a lot off her. She helped with my training, so she's someone that I

really respect. [Interviewee 4]

“But not that I have got this information from a colleague and then I have to call

another one to get information on behalf of the first colleague. ”[Interviewee 2]

Case based learning

“They don’t provide notes they just give you a description of what the case is with the

photographs. They’re always consented. People then comment or criticise or

appraise, or be supportive of the results.” [Interviewee 1]

“And just out of interest, looking at the other people’s cases. And of course, to see

how I can improve.”[Intervewee1]

“I quite like it. I mean I believe dentistry as a profession is very open to discussing

cases.” [Interviewee 5]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-51-320.jpg)

![52

Formal learning

Knowledge seeking-acquiring by reading, learning, speaking and listening as well as

participation in conferences. Dentists seek and acquire knowledge by regularly

reading dental journals, which is not only specific to one area but cover, all areas of

the dentistry. It means dentists are more keen to see the interesting information.

“So Dental Update is a journal that covers all areas of dentistry not particularly

targeted at one area of dentistry and that’s why I find it interesting because it’s not

just one thing. It’s very broad. It’s very easy to read so it’s quite clearly written so …

and it keeps the interest there so you don’t get bored whilst reading it.”

[Interviewee 6]

“Well the societies that I’m members of, they release journals regularly, every…

depending on the association… every month, every quarter I’ll get a journal through

the post and I read that. So that’s probably the biggest input because it comes

through my letterbox and I read that every month.” [Interviewee 5]

“Yeah. Listening and watching presentations. Reading what’s on the presentations.”

[Interviewee 6]

“I only go to the SAAD conference once a year. And the Dental Sedation Teachers'

group conference once a year.” [Interviewee 4]

“However, I also go to the conferences, especially if I’m part of the local meetings,

then they’re much easier to get to, so I can go on my way home from work and quite

often they have from six to nine o’clock they’ll do a lecture on a particular topic or

they’ll do an update on where the NHS is going and the future for the contracts and

things like that.” [Interviewee 5]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-52-320.jpg)

![53

Reason for knowledge seeking-acquisition

Dentists felt that they seek-acquire knowledge so that they can be updated with

latest information and knowledge’s what they are lacking. It also reflects that

dentists are keen and enthusiastic to learn and develop their skills.

Keep updated with knowledge and improve your knowledge

“New knowledge, new research, new developments. Just to be updated on what’s

happening.” [Interviewee 3]

“It’s just to (a) give advice, (b) to get more information, (c) to see what’s out there at

the moment to keep myself updated, am I falling behind? And just out of interest,

looking at the other people’s cases. And of course, to see how I can improve.”

[Interviewee 1]

“Well, I guess it makes me think about different techniques I can use, or gives me a

broader knowledge of the medical aspects of patient care.” [interviewee 4]

Influences on knowledge sharing

The third minor theme was influences of knowledge sharing. Dentists felt positive

that most of the dentists working in the hospital believe that it is a professional

responsibility, as well as satisfaction, for sharing knowledge. Dentists also reported

that they share knowledge as it gives them confidence as well as feeling appreciative

and rewarding. On the other hand some dentists had a judgemental perception

about sharing knowledge where dentists would assess the level of understanding

and decide to share knowledge after assessing who is asking. Similarly, dentists also

felt that they wouldn’t share knowledge if they were uncertain about something.

They will only share which is definite and evidence based. Dentists also perceived a

influence of political barrier would resist them to share knowledge, as they believe

their opinion will not be given importance and only people with high power are

given consideration

The finding in regards to influences on dentist for knowledge sharing includes:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-53-320.jpg)

![54

Professional satisfaction and responsibility

The participants who are working in a university teaching hospital feel it is their

responsibility to share their knowledge with patients, colleagues and students.

“I’m a Clinical Academic in a way, I’m a teacher, so it’s a part of my job. It’s one of

the reasons why I’m doing this job, so obviously it’s part of my professional

satisfaction.” [Interviewee 2]

“It’s my job actually. It’s what I have to do.” [Interviewee 3]

Perceived happiness and rewarding

“I find it interesting, I find it rewarding, you know helping people to learn, I do find it

quite rewarding.” [Interviewee 6]

“ I feel quite confident because I have the knowledge.” [Interviewee 4]

“No, I'm quite happy to share my knowledge with anyone.” [Interviewee 3]

Judgemental perception

“you’ve got to look at who’s asking and then decide whether it’s gonna be

appropriate to, what sort of level of information they need to know to manage the

case” [Interviewee 1]

“I think I would not share knowledge if I wasn’t a hundred percent sure on the thing

that I was trying to share. So I would make sure I’d check first before sharing such

knowledge.” [Interviewee 6]

Similarly dentist perceived sometimes it is necessary to gain understanding and

rationale of being asked, even though the information is easily available and they

have not tried to look it up themselves or followed simple instruction. This will lead

them to be reluctant to share knowledge.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-54-320.jpg)

![55

“Of course the other reason is sometimes what is the rationale for someone asking

for this information? To give an example sometimes people just want to scratch the

surface instead of following an organised educational pathway. For example, they

will ask you how to do this instead of trying to find out whyit should be done. In

some cases, some people want to be spoon-fed with an easy question to them, so

probably some maybe a little bit reluctant to share information.” [Interviewee 2]

Perceived political barriers:

“So when these politics and these guiding forces sometimes fail to maintain an

equilibrium and to be presented as fair and only specific people there are preferred to

do presentations, or specific scientific dogmas if you prefer. Then I may have a

problem….” [Interviewee 2]

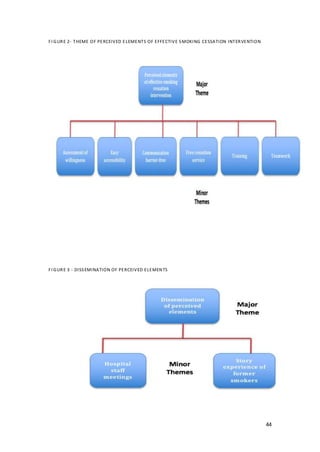

Section 3 - Perceived elements of effective intervention smoking cessation

The third section was to know their opinion on effective and efficient smoking

cessation advice. These are the following elements, which dentists perceived would

be ideal to make smoking cessation effective in hospital practice:

Assessment of willingness will incline them to give effective smoking cessation

advice

Dentists’ felt to assess the willingness of patients to quit tobacco is important and

will incline them to provide them with smoking cessation service and advice.

Dentists also believe that if patients are willing to quit then this shows a sign of

motivation. Similarly, dentists also feel that patients initially show a willingness to

quit smoking but later they become unsure to quit or are not so certain.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-55-320.jpg)

![56

“And we would ask the question about quitting, if they have tried quitting or if they

are interested in quitting and based on that we might give the number or otherwise

we will just say whenever you are ready there is the number or we will be able to

point you in the right direction.” [Interviewee 3]

“If we see that the patient really would like to stop smoking and there are signs of

motivation but finds it very difficult for biological reasons to stop smoking, then

through the patient’s….” [Interviewee 2]

“Whether they have any interest in smoking cessation because a lot of people will say

I thought about quitting but I’ve just not got around to it.” [Interviewee 5]

Easy accessibility:

The research found most of the dentists believe there is no easy accessibility for

patients and even for dentists themselves. There should be joint clinics set up

together with the dentists in the hospital clinics so it is made easily accessible for

dentists, as well as well patients, to get smoking cessation advice there and then. It is

perceived that providing quick help there and then will be beneficial for saving time

and future visits for dentists, as well as patients, and believed this would lead to

more chances of accepting the cessation advice in the future. It will be more

effective if accessibility is taken into consideration and given more importance.

Dentists also perceived, from a language point of view, there should be easy access

both for patients and dentists to make an effective intervention. Dentists specified

language is a barrier for them to give effective assistance. The hospital is located

where there is a diverse community population of people, and where the population

speak different languages, this can be an occasional problem.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-56-320.jpg)

![57

“An ideal situation, in my opinion, would be maybe a joint clinic to have the cessation

specialist with me or running their clinic alongside mine so it’s easily accessible.”

[Interviewee 6]

“Well because if you had a smoking cessation team that could access a role or can

come to the clinic so you don't have to refer the patient.” [Interviewee 4]

On the other hand, another option would be to provide a referral service in one’s

neighbourhood or nearby rather than another location, which will be difficult for the

patient get to.

“And there are also a lot of pharmacies nearby who give a lot of advice as well, so

we’d normally refer to these but we always put the seed there.” [Interviewee 1]

The interest finding was to provide easy accessibility with the use of technology by

providing tele-care cessation service with help of social media use of Skype or

Babylon application. Which will be a convenient way to give effective services.

“I suppose the other way you could do tobacco cessation is by tele-technology. So

Skype, make use of social media. So you can refer a patient, I don't know, you can

say if you had a service that provided some kind of telemedicine or cessation via

Skype, then that would reduce the amount of time that the patient would spend

getting here. And it would be more flexible for the patient.” [Interviewee 4]

“Also a problem in this are particularly is that language is a barrier so something

that’s easy accessible from the language point of things for our patients who don’t

speak English is also an ideal… “ [Interviewee 6]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-57-320.jpg)

![58

“If somebody does not speak the same language as me it’s difficult for them to

understand what I’m telling them. If you’re also relying on someone to translate,

you’re not entirely sure exactly whether they’re translating it one hundred percent

and you usually have a gut feeling if you know that they’re not fully telling the whole

information but you can’t be a hundred percent sure.” [Interviewee 6]

Communication barriers free between smoking cessation services and dentists

The finding is that there are lots of hurdles in referral service for person. Its not

running smoothly and effectively as it should be. There is no confirmation for

dentists who will be assured that the referral is under process, which will motivate

them to continue using services and also to maintain clinical records of these. They

would need to develop a system to effectively communicate so the dentist receives

feedback. They should receive a confirmation either through letter or email for an

effective cessation referral service.

“Yes, that would be a good idea would be that if there’s something either on their

clinical record or if there’s an e-mail confirmation. Something on their clinical record

would be much easier because anyone can access it, anyone who’s looking after the

patient…” [Interviewee 6]

“Yeah, obviously the communication is the key. I mean what usually happens is that

we say to tick the box you have to go there, and then that’s it. Rarely we get any

feedback or any outcome, or any summary of the results of this programme. Mostly

the patient comes back and describes what they get out of this.” [Interviewee 2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-58-320.jpg)

![59

Free cessation service

Dentists felt to give a smoking cessation service in an NHS hospital, there should not

be a concern of cost to provide an effective smoking cessation service.

“ In the NHS you don’t charge for it.” [Interviewee 1]

“Financially I think the NHS is in place to help with that actually. There is no charge

for that. In the hospital there is no charge.” [Interviewee 3]

Training and information for auxiliary staff and dentist

The fifth element, which dentists reported, is there is a lack of training for dentists

and their staff to deliver an effective smoking cessation service. Dentists felt nurses

and auxiliary staff should be well trained so they can assist dentists in providing an

effective service. Therefore dentists suggest dental nurses and other hospital staff

should be given at least basic foundation training in regards to smoking cessation.

Some dentists had even provided examples where dental nurses can give preventive

advice, which seem to be feasible for oral health promotion. It would be best to

integrate smoking cessation advice along with preventive advice, which was also

reported by dentists who have a role of clinical teacher and also suggest integrating

this in the dental student curriculum in prevention modules.

“I think so. I don’t think you can be offering smoking cessation if you don’t know

what you’re talking about, so I think training to make sure everyone has a good

foundation knowledge before they start would be a very clever idea.” [Interviewee 5]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-59-320.jpg)

![60

“I suppose you can give them a one or two day course, I don't think it needs more

than that. Set up a smoking cessation team, just to make them aware of things.”

[Interviewee 4]

“At this stage I think that very few dentists really have any training or even education

on what is the problem with smoking, how extensive it is, and how you can manage

this, or even how they can participate at the first stages of a smoking cessation

programme.” [Interviewee2]

Teamwork

Dentists working as a team, with their auxiliary staff and other fellow dentists, would

be more likely to effectively deliver a smoking cessation service. Dental nurses play a

vital role along with dentist working in hospital, who are busy providing advanced

skill works. It also presents a back up if a dentist forget something the nurse can act

as reminder for them.

“My hope would be if you had say a dentist and a nurse working side by side and the

dentist forgot, I would hope that the nurse would give them a quick nudge and say do

you want to ask about tobacco use. So it’s sort of two brains are better than one in

that sense, in the hope that both of them wouldn’t forget” [Interviewee 5].

“Yes, I think most people in the team should, could be involved in this. Other

clinicians and nurses as well. Yes, I’m sure if something like that could happen then

I’m sure everyone would be involved.” [Interviewee 6]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-60-320.jpg)

![61

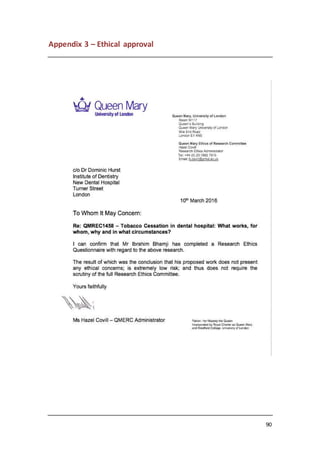

Section 4 - Disseminate perceived elements of effective tobacco cessation

intervention with colleagues in hospital

The last section presents how dentists disseminate this effective approach to others.

The study found all participants would likely disseminate knowledge with their

colleagues in hospitals through meetings and presenting them the evidence by

working with them and sharing stories of ex-smokers.

Hospital Meeting

The common finding presented most of the dentists in their hospital setting will

disseminate effective intervention through meetings. Evidence, which can

specifically create more interest in other colleagues and members to adopt that

particular which is effective.

“If nothing has been done, then the first thing you’d want is a meeting, at a hospital

meeting, just bring it up, and say we need to have this policy, we need to help people

give up smoking or chewing tobacco.” [Interviewee 1]

“Now regarding the sharing information, what we quite often do in hospital is we

have a team meeting, so have a staff meeting, everyone brings a slice of cake, its

lovely, and you sit around and you say, we’re going to do this and we’re going to do

this because and this is how you do it.” [Interviewee 5]

“Invite everyone to come a specific day and time and maybe invite other speakers

and prepare more organised session.” [Interviewee 3]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-61-320.jpg)

![62

Stories of former smokers

“Yeah, I guess having stories from ex-smokers, people who have actually

implemented it elsewhere, that helps. These days with communications through

electronic devices it’s pretty easy to achieve that and organise”. [Interviewee 1]

“So if you had it, if you used it on a group of patients for example. If you can

demonstrate from the patients that A it didn’t take much time from them, B it didn’t

take any time from you and the surgery and C it was effective”. [Interviewee 4]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-62-320.jpg)

![76

References:

1. Glossary of term use in the tobacco atlas. [Online].Available:

http://www.who.int/tobacco/en/atlas42.pdf [Accessed].

2. 2015. Smoking:supportingpeopleto stop| List-of-quality-statements|Guidance

and guidelines|NICE.

3. AGEE, J. 2009. Developing QualitativeResearch question:a reflective process.

[Online].Taylorandfrancisgroup.Available:

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09518390902736512 [Accessed].

4. AHMADY, A.E., HOMAYOUN, A.,LANDO,H. A.,HAGHPANAH,F.& KHOSHNEVISAN,

M. H. 2014. Patients'attitudestowardsthe role of dentistsintobaccocessation

counsellingafterabrief andsimple intervention. Eastern Mediterranean Health

Journal, 20, 82-89.

5. AKL,E. A., JAWAD,M., LAM, W. Y., CO,C. N.,OBEID, R. & IRANI,J.2013. Motives,

beliefsandattitudestowardswaterpipe tobaccosmoking:asystematicreview.

Harm Reduction Journal, 10, 9.

6. AL-BUSAIDI,Z.Q. 2008. Qualitative ResearchanditsUsesinHealthCare. Sultan

QaboosUniv Med J.

7. ALAN FROST.2010. Communitiesof Practice [Online].Available:

http://www.knowledge-management-tools.net/communities-of-practice.html

[Accessed].

8. AMEMORI, M., FINLAND,U. O. H. D. O. O.P. H. I. O.D. H.,KORHONEN,T.,FINLAND,

U. O. H. D. O. O. P.H. I.O. D. H., FINLAND,U.O. H. D. O. P. H. H. I. H., MICHIE, S.,

UNIVERSITYCOLLEGE LONDON CENTRE FOR OUTCOMES RESEARCH AND

EFFECTIVENESSDEPARTMENTOF CLINICAL,E. A.H. P. L. U., MURTOMAA, H.,

FINLAND,U.O. H. D. O. O. P. H. I.O. D. H., KINNUNEN,T.H. & USA, H. U. D. O.O. H.

P. A.E. H. S. O. D. M. B. M. 2015. Implementationof tobaccouse cessation

counselingamongoral healthprofessionalsinFinland. Journalof PublicHealth

Dentistry, 73, 230-236.

9. AMEMORI, M., VIRTANEN,J.,KORHONEN,T.,KINNUNEN,T.H. & MURTOMAA, H.

2013. Impactof educational interventiononimplementationof tobaccocounselling

amongoral healthprofessionals:acluster-randomizedcommunitytrial. Community

Dent Oral Epidemiol, 41, 120-9.

10. AMTHA, R.,RAZAK,I. A.,BASUKI,B.,ROESLAN,B. O.,GAUTAMA, W., PUWANTO,D.

J.,GHANI, W. M. & ZAIN,R. B. 2014. Tobacco (kretek) smoking,betel quidchewing

and riskof oral cancer ina selectedJakartapopulation. Asian PacJCancerPrev, 15,

8673-8.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-76-320.jpg)

![77

11. ANDREWS,K. M., TECHNOLOGY, Q.U. O.,DELAHAYE, B. L. & TECHNOLOGY,Q. U. O.

2016. InfluencesOnKnowledge processesInOrganizationalLearning:The

Psychosocial Filter. Journalof ManagementStudies, 37,797-810.

12. ASEMAHAGN,M. A. 2014. Knowledge andexperience sharingpracticesamong

healthprofessionalsinhospitalsunderthe AddisAbabahealthbureau,Ethiopia.

BMC HealthServ Res.

13. BALA,M. M., STRZESZYNSKI,L.,TOPOR‐MADRY,R. & CAHILL, K.2015. Mass media

interventionsforsmokingcessationinadults.

14. BALEY, J. 2007. Social Care Online | Teamworking in healthcare:longitudinal

evaluation of a teambuilding intervention [Online].:.Available: http://www.scie-

socialcareonline.org.uk/teamworking-in-healthcare-longitudinal-evaluation-of-a-

teambuilding-intervention/r/a1CG0000000Gdx0MAC [Accessed].

15. BARWICK,M. A.,PETERS, J. & BOYDELL, K. 2009. Gettingto Uptake:Do Communities

of Practice Supportthe Implementationof Evidence-BasedPractice?JCan Acad

Child AdolescPsychiatry.

16. BAULD, L., BELL, K., MCCULLOUGH, L., RICHARDSON,L.& GREAVES,L. 2010. The

effectivenessof NHSsmokingcessationservices:asystematicreview.

17. BME- STOPTOBACCOPROJECT2016. Tobacco and Dentistryfocusgroup:patient

and publicengagement.

18. BOTELLO-HARBAUM, M. T., DEMKO, C. A.,CURRO, F. A.,RINDAL,D. B.,COLLIE, D.,

GILBERT, G. H.,HILTON, T. J.,CRAIG, R. G.,WU, J.,FUNKHOUSER, E., LEHMAN,M.,

MCBRIDE, R., THOMPSON,V. & LINDBLAD,A.2013. Information-SeekingBehaviors

of Dental PractitionersinThree Practice-BasedResearchNetworks. JDentEduc, 77,

152-60.

19. BOWER, E., DEPARTMENT OF ORALHEALTH SERVICESRESEARCHAND DENTAL

PUBLIC HEALTH, K. S. C.L. D. I.,LONDON UK, SCAMBLER, S. & DEPARTMENT OF

ORAL HEALTH SERVICESRESEARCH ANDDENTAL PUBLIC HEALTH, K. S. C. L. D. I.,

LONDON UK 2007. The contributionsof qualitative researchtowardsdental public

healthpractice. CommunityDentistry and OralEpidemiology, 35,161-169.

20. BRADLEY, E. H., CURRY, L. A. & DEVERS, K.J. 2007. Qualitative DataAnalysisfor

HealthServicesResearch:DevelopingTaxonomy,Themes,andTheory. Health Serv

Res, 42, 1758-72.

21. BRAUN,V. & CLARKE,V. 2006. Using thematicanalysisinpsychology.

22. BRITISH THORACICSOCIETY.2012. Recommendation forhospital smoking cessation

services forcommissionersand health professionals. [Online].Available:

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/smoking-

cessation/bts-recommendations-for-smoking-cessation-services/ [Accessed].

23. BROWN,J. S. & DUGUID, P.1991. Organizational Learningand Communities-of-

Practice:Toward a UnifiedViewof Working,Learning,andInnovation. Organization

Science, 2, 40-57.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-77-320.jpg)

![78

24. BRYMAN, A.2016. Social Research Methods., Oxford.,Oxforduniversitypress.

25. BURNARD,P., GILL, P.,STEWART, K.,TREASURE, E. & CHADWICK, B.2008. Analysing

and presentingqualitative data. British DentalJournal, 204, 429-432.

26. CALLINAN,J.E.,CLARKE, A.,DOHERTY, K. & KELLEHER, C.2010. Legislative smoking

bans forreducingsecondhandsmoke exposure,smokingprevalence andtobacco

consumption. CochraneDatabaseSystRev,Cd005992.

27. CARR,A. B. & EBBERT, J. 2012. Interventionsfortobaccocessationinthe dental

setting. CochraneDatabaseSystRev, 6,Cd005084.

28. CENTRE.,H. A.S. C. I.2006. HealthsurveyforEngland-2004: Healthof ethnic

minorities,Headlineresults[NS].

29. CHESTON,C. C., FLICKINGER,T.E. & CHISOLM, M. S. 2013. Social mediause in

medical education:asystematicreview. Acad Med, 88,893-901.

30. CHRCANOVIC,B.R.,ALBREKTSSON,T.& WENNERBERG,A. 2015. Smokinganddental

implants:A systematicreview andmeta-analysis. Journalof Dentistry, 43, 487-498.

31. COFFEY,A. & ATKINSON,P.1996. Narrativesand storie.In making senseof

qualitativedata. [Online].Thousandoaks,CA:Sage publiser.Available:

http://academic.son.wisc.edu/courses/n701/week/Narrativesandstories.pdf

[Accessed].

32. CONTREARY,K. A.,CHATTOPADHYAY,S.K.,HOPKINS,D.P., CHALOUPKA,F.J.,

FORSTER,J. L., GRIMSHAW, V.,HOLMES, C. B., GOETZEL, R. Z., FIELDING,J. E. &

COMMUNITY PREVENTIVESERV,T. 2015. EconomicImpact of Tobacco Price

IncreasesThroughTaxationA CommunityGuide SystematicReview. American

Journalof PreventiveMedicine, 49, 800-808.

33. CRESWELL, J. 2009. Research design:Qualitative,Quantitativeand mixed methods

approaches.,Sage.

34. CSIKAR,J.,WILLIAMS,S. A. & BEAL, J.2009. Do smokingcessationactivitiesaspart of

oral healthpromotionvarybetweendental care providersrelativetothe

NHS/private treatmentmix offered?A studyinWestYorkshire. PrimDentCare, 16,

45-50.

35. CURRAN,J. A.,MURPHY, A.L., ABIDI,S. S.,SINCLAIR,D.& MCGRATH, P. J.2009.

Bridgingthe gap: knowledge seekingandsharingina virtual communityof

emergencypractice. EvalHealth Prof, 32, 312-25.

36. CURRO, F. A.,GRILL, A. C.,THOMPSON,V.P., CRAIG,R. G., VENA,D.,KEENAN,A.V.

& NAFTOLIN,F.2011. Advantagesof the Dental Practice-BasedResearchNetwork

Initiative andItsRole inDental Education. JDentEduc, 75, 1053-60.

37. DALIA,D., PALMER,R. M. & WILSON,R. F. 2007. Managementof smokingpatients

by specialistperiodontistsandhygienistsinthe UnitedKingdom. JClin Periodontol,

34, 416-22.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-78-320.jpg)

![79

38. DASH,N. 2005. Research MethodsResource- Selection of the Research Paradigm

and Methodology [Online].Available:

http://www.celt.mmu.ac.uk/researchmethods/Modules/Selection_of_methodology

/ [Accessed].

39. DAWES,M. & SAMPSON,U. 2003. Knowledgemanagementinclinical practice:a

systematicreviewof informationseekingbehaviorinphysicians. IntJMed Inform,

71, 9-15.

40. DENZIN,N.& LINCOLN,Y.S. 2003. The landscapeof QualitativeResearch;Theories

and issues, California,sage publication.

41. DICICCO‐BLOOM,B.,DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY MEDICINE,U. O. M. A. D. A.R. W. J.

M. S.,SOMERSET, NEW JERSEY, USA, CRABTREE,B. F. & DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY

MEDICINE, U. O. M. A. D. A.R. W. J. M. S.,SOMERSET, NEW JERSEY, USA 2006. The

qualitative researchinterview. MedicalEducation, 40,314-321.

42. EDWARDS,D., FREEMAN, T. & ROCHE, A.M. 2006. Dentists'anddental hygienists'

role insmokingcessation:anexaminationand comparisonof currentpractice and

barriersto service provision. Health PromotJAustr, 17, 145-51.

43. ETIENNE ANDBEVERLY WENGER-TRAINER.2015. Introduction to communitiesof

practice | Wenger-Trayner[Online].Available:http://wenger-

trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/ [Accessed].

44. EUROPEAN COMMISSION.2015. Attitudesof EuropeansTowardstobacco 2015.

[Online].Available:

http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/docs/2015_infograph_en.pdf [Accessed

December2015].

45. FORD,P., QUEENSLAND,T. U. O. Q. S. O.D. B., TRAN,P.,QUEENSLAND,T. U. O. Q. S.

O. D. B.,QUEENSLAND,T. U. O. Q. U. C. F. C. R. H.,KEEN, B.,QUEENSLAND,T. U. O.

Q. U. C. F. C. R. H., GARTNER,C. & QUEENSLAND,T. U. O. Q.U. C. F.C. R. H. 2015.

Surveyof Australianoral healthpractitionersandtheirsmokingcessationpractices.

Australian DentalJournal, 60, 43-51.

46. FOWKES,F. J.,STEWART, M. C., FOWKES,F. G., AMOS,A. & PRICE,J. F. 2008.

Scottishsmoke-free legislationandtrendsinsmokingcessation. Addiction, 103,

1888-95.

47. FUGARD, A.J. B. & POTTS, H. W. W. 2015. Supportingthinkingonsample sizesfor

thematicanalyses:aquantitative tool.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1005453.

48. FUGILL, M. 2012. Tacit knowledgeindental clinical teaching. EurJDent Educ, 16, 2-

5.

49. GABBAY,J. & MAY, A.L. 2004. Evidence basedguidelinesorcollectivelyconstructed

“mindlines?”Ethnographicstudyof knowledge managementinprimarycare.

50. GANDINI,S.,DIVISION OFEPIDEMIOLOGYANDBIOSTATISTICS,E.I. O. O.,MILAN,

ITALY, DIVISION OFEPIDEMIOLOGYAND BIOSTATISTICS,E.I.O. O.,VIA RIPAMONTI

435, 20141 MILAN,ITALY, BOTTERI, E.,DIVISION OFEPIDEMIOLOGY AND](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-79-320.jpg)

![80

BIOSTATISTICS,E.I. O.O., MILAN,ITALY, IODICE,S.,DIVISION OFEPIDEMIOLOGY

ANDBIOSTATISTICS,E.I. O. O.,MILAN,ITALY, BONIOL,M., INTERNATIONALAGENCY

FOR RESEARCH ON CANCER,L., FRANCE,LOWENFELS,A.B., DEPARTMENT OF

SURGERY, N.Y. M. C.,VALHALLA,NY,DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY AND

PREVENTIVEMEDICINE,N.Y. M. C., VALHALLA,NY,MAISONNEUVE,P.,DIVISION OF

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND BIOSTATISTICS,E.I.O. O.,MILAN, ITALY,BOYLE, P. &

INTERNATIONALAGENCYFORRESEARCH ON CANCER,L., FRANCE2015. Tobacco

smokingandcancer: A meta‐analysis. InternationalJournalof Cancer, 122, 155-164.

51. GARLAND,A.F., KRUSE, M. & AARONS,G.A.2003. Cliniciansandoutcome

measurement:what'sthe use? JBehav Health Serv Res, 30, 393-405.

52. GDC. 2013. Standardsfordentalprofessionals [Online].General DentalCouncil.

Available:http://www.gdc-

uk.org/dentalprofessionals/standards/pages/default.aspx [Accessed].

53. GIALDINO.,I.V.D. 2009. Ontologicaland Epistemologicalfoundation of Qualitative

research [Online].Available: http://www.qualitative-

research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1299/3163 [Accessed].

54. GILL, P., STEWART,K., TREASURE, E. & CHADWICK,B. 2008. Methodsof data

collectioninqualitativeresearch:interviewsandfocusgroups. British Dental

Journal, 204, 291-295.

55. GLOSSARY,C. 2016. Resources|Cochrane Tobacco Addiction.

56. GOLAFSHANI,N.2003. Understanding Reliability and Validity in QualitativeResearch

[Online].ontario:universityof toronto.Available:

http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR8-4/golafshani.pdf [Accessed].

57. GONZALEZ-MARTINEZ,R.,DELGADO-MOLINA,E.& GAY-ESCODA,C. 2012. A survey

of oral surgeons'tobacco-use-relatedknowledgeandinterventionbehaviors.

Medicina Oral Patologia OralY Cirugia Bucal, 17, E588-E593.

58. GORDON,J. S.,ANDREWS,J. A.,ALBERT, D. A.,CREWS, K. M., PAYNE,T. J.&

SEVERSON,H.H. 2010. Tobacco CessationviaPublicDental Clinics:Resultsof a

RandomizedTrial. AmJPublic Health.

59. GUEST, G., MACQUEEN, K.M. & NAMEY, E. E. 2012. Applied thematic analysis.,

California,sage publication.

60. HALCOMB, E. & DAVIDSON,P.2006. Is verbatimtranscriptionof interview data

alwaysnecessary? - PubMed - NCBI.

61. HANSON SMITH, E. 2013. OnlineCommunitiesof practice,The encyclopaedia of

applied Lingustics. [Online].Available:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/9781405198431/asset/homepages/7_

Online_Communities_of_Practice.pdf?v=1&s=cfd3645273384e59ea802c0d8cb2ab8

7e98054c4 [AccessedJuly2016.].

62. HAYES, G. R., CENTER,C. O. C. G., PATEL,S. N.,CENTER, C. O.C. G., TRUONG, K. N.,

CENTER, C. O.C. G., IACHELLO,G., CENTER, C. O. C. G.,KIENTZ,J. A.,CENTER, C. O. C.

G., FARMER, R.,CENTER, C. O. C. G., ABOWD,G. D. & CENTER, C. O. C. G. The](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-80-320.jpg)

![81

Personal AudioLoop:DesigningaUbiquitousAudio-BasedMemoryAid. Mobile HCI,

2016. SpringerBerlinHeidelberg,168-179.

63. HEALTH ANDSOCIALCARE INFORMATION CENTRE.2015. Statistics on smoking,

England. [Online].HealthandSocial Care InformationCentre,1TrevelyanSquare,

Boar Lane,Leeds,LS1 6AE, UnitedKingdom.Available:

http://www.hscic.gov.uk/article/2021/Website-

Search?productid=17945&q=health+survey+for+england&sort=Relevance&size=10&

page=1&area=both [AccessedDecmber2015].

64. HOLLIS, J.,MCAFEE, T., FELLOW, J.,ZBISKWOSKI,S.,STARK,M. & REIDLINGER, K.

2007. The effectivenessand costeffectivenessof telephonecounselling and nicotine

patch in a statetobacco quitline. [Online].Available:

http://m.tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/16/Suppl_1/i53.full [Accessed].

65. HOSSAIN,M. S.,KYPRI,K.,RAHMAN,B., AKTER,S. & MILTON, A. H. 2015. Health

knowledge andsmokelesstobaccoquitattemptsandintentionsamongmarried

womeninrural Bangladesh:Cross-sectionalsurvey. Drug AlcoholRev.

66. HSIEH, H. S.,SE. 2006. Three Approachestoqualitative contentanalysis.:Sage

Publications.

67. HUGHES, D. L. & DUMONT, K.2016. Using FocusGroups to Facilitate Culturally

AnchoredResearch.257-289.

68. HULLEY, S. B. 2001. Designing clinical research : an epidemiologicapproach,

Philadelphia,LippincottWilliams&Wilkins.

69. ISHAM, A.,BETTIOL, S.,HOANG,H. & CROCOMBE,L. 2016. A SystematicLiterature

Reviewof the Information-SeekingBehaviorof DentistsinDevelopedCountries.

70. JACKSON,S.E.,CHUANG,C.H.,HARDEN,E.,JIANG,Y.,ANDJOSEPH,J.M.2006. Research

in Personneland Human ResourcesManagement:Research in Personnel and Human

ResourcesManagement.

71. JASIMUDDIN,S. M., KLEIN,J. H.,CONNELL,C., CHAHARBAGHI,K.,ADCROFT,A.&

WILLIS, R.2012. The paradox of usingtacit and explicitknowledge.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00251740510572515.

72. JOHN,J. H., THOMAS,D. & RICHARDS,D. 2003. Smokingcessationinterventionsin

the Oxfordregion:changesindentists'attitudesandreportedpractices1996-2001.

Br Dent J, 195, 270-5; discussion261.

73. JOHN,J. H., YUDKIN,P.,MURPHY, M., ZIEBLAND,S. & FOWLER, G. H. 1997. Smoking

cessationinterventionsfordental patients--attitudesandreportedpracticesof

dentistsinthe Oxfordregion. BrDentJ, 183, 359-64.

74. JOHNSON,N.W.,LOWE, J. C. & WARNAKULASURIYA,K.A.2006. Tobacco cessation

activitiesof UKdentistsinprimarycare:signsof improvement. BrDentJ, 200, 85-9.

75. JONES,A.M., LAPORTE, A.,RICE, N.& ZUCCHELLI, E. 2015. Do publicsmokingbans

have an impacton active smoking?Evidence fromthe UK. Health Econ, 24, 175-92.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-81-320.jpg)

![82

76. KHAN,Z.,TONNIES,J.& MULLER, S. 2014. Smokelesstobaccoandoral cancer in

SouthAsia:a systematicreview withmeta-analysis. JCancerEpidemiol, 2014,

394696.

77. KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT. 2005. KnowledgemanagementGlossary. [Online].

Available:

http://www.asocam.org/biblioteca/files/original/f36c1f8550884273e2cbeb23a7f2b

7e7.pdf [Accessed].

78. KOTHARI,A.,RUDMAN, D., DOBBINS,M.,ROUSE, M., SIBBALD,S. & EDWARDS,N.

2012. The use of tacit andexplicitknowledge inpublichealth:aqualitative study.

ImplementSci, 7, 20.

79. KUMAR, R. 2014. Research Methodology;a step by step guidefor beginners.,

London,Sage publisher.

80. LAVE,J. & WENGER, E. 1990. Situated learning:legitimateperipheralparticipation.,

Cambridge UniversityPress.

81. LEE, P. N.,FOREY, B. A.& COOMBS,K. J. 2012. Systematicreview withmeta-analysis

of the epidemiological evidence inthe 1900s relatingsmokingtolungcancer. BMC

Cancer, 12, 1.

82. LEE, P. N. & HAMLING, J.2009. Systematicreview of the relationbetweensmokeless

tobacco and cancer inEurope and NorthAmerica. BMCMed, 7, 36.

83. LEGARD, R., KEEGAN,J. & WARD,K. In-depth interviews. [Online].Available:

http://www.scope.edu/Portals/0/progs/med/precoursereadings/IEIKeyReading5.pd

f [Accessedjune 2016].

84. LI, L. C., GRIMSHAW,J. M., NIELSEN,C., JUDD, M., COYTE, P. C. & GRAHAM, I.D.

2009. Use of communitiesof practice inbusinessandhealthcare sectors:A

systematicreview. Implementation Science, 4,1.

85. MAINALI,P.,PANT,S.,RODRIGUEZ, A.,DESHMUKH, A.& MEHTA, J. L. 2015. Tobacco

and CardiovascularHealth.

86. MARSHALL, C. & BOSSMAN,G. 2006. Designing QualitativeResearch, Delhi and

London,sage.

87. MCCARTAN,B.,MCCREARY, C. & HEALY, C.2008. Attitudesof Irishdental,dental

hygiene anddental nursingstudentsandnewlyqualifiedpractitionerstotobacco

use cessation:A national survey. EuropeanJournalof DentalEducation, 12, 17-22.

88. MEAGHER-STEWART, D., SOLBERG, S.M., WARNER,G., MACDONALD,J.-A.,

MCPHERSON,C. & SEAMAN,P. 2012. Understandingthe Role of Communitiesof

Practice inEvidence-InformedDecisionMakinginPublicHealth.

89. MURRAY, R. L.,BAULD, L., HACKSHAW,L. E. & MCNEILL, A. 2009. Improvingaccess

to smokingcessationservicesfordisadvantagedgroups:asystematicreview. J

Public Health (Oxf), 31,258-77.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-82-320.jpg)

![83

90. NARGIS,N.,THOMPSON,M. E., FONG,G. T.,DRIEZEN, P.,HUSSAIN,A.K., RUTHBAH,

U. H., QUAH, A. C. & ABDULLAH, A.S. 2015. Prevalence andPatternsof TobaccoUse

inBangladesh from2009 to 2012: Evidence fromInternational TobaccoControl (ITC)

Study. PLoSOne, 10, e0141135.

91. NASSER,M. 2011. Evidence summary:issmokingcessationaneffective andcost-

effectiveservice tobe introducedinNHSdentistry? BrDentJ, 210, 169-77.

92. NATIONALINSTITUTEFOR HEALTH AND CAREEXCELLENCE, N. 2006. Smoking:brief

interventionsand referrals| Guidanceand guidelines| NICE [Online].NICE.

Available:https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph1[Accessed].

93. NICE2015. Uptake | SupportingPeople toStopSmoking|Guidance andguidelines|

NICE.

94. NONAKA,I.1994. A DynamicTheoryof Organizational Knowledge Creation.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14.

95. NONAKA,I.&TOYAMA, R. 2002. A firmas a dialectical being:towardsadynamic

theoryof a firm.

96. PANDA,R.,PERSAI,D.,VENKATESAN,S.&AHLUWALIA,J. S. 2015. Physicianand

patientconcordance of reportof tobaccocessationinterventioninprimarycare in

India. BMCPublic Health, 15, 456.

97. PARROTT,S. & GODFREY, C. 2004. Economicsof smokingcessation.

98. PATEL, S.2015. Saturationinqualitative researchsamples.

99. POLAND,B.1995. Transcription Quality as an aspectof Rigorin QualitativeResearch

[Online].Toronto:Sage Publications.Available:

http://m.qix.sagepub.com/content/1/3/290.short [Accessed].

100. POLANYI,M. 1966. The Tacit Dimension. --.GloucesterMA:PeterSmith4-

polanyani M,1966.

101. POPE,C., ZIEBLAND,S.& MAYS, N. 2000. Analysingqualitative data.

102. PUBLIC HEALTH ENGLAND.2014. Smokefreeand smiling - Publications -

GOV.UK [Online].Available:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/smokefree-and-smiling[Accessed].

103. RAHAGHI,F. F.,HERNANDEZ,F. & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2016. Smoking

cessation.

104. RAMÓN,J. M., EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH, S. O.D., UNIVERSITY

OF BARCELONA,BARCELONA,SPAIN,ECHEVERRÍA,J.J.& AND,D. O. P.2015. Effects

of smokingonperiodontaltissues. Journalof Clinical Periodontology, 29,771-776.

105. RANMUTHUGALA, G., CUNNINGHAM,F.C., PLUMB, J.J., LONG,J.,

GEORGIOU, A.,WESTBROOK,J. I. & BRAITHWAITE,J. 2011a. A realistevaluationof

the role of communitiesof practice inchanginghealthcare practice. ImplementSci,

6, 49.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-83-320.jpg)

![84

106. RANMUTHUGALA, G., PLUMB, J.J., CUNNINGHAM,F.C., GEORGIOU, A.,

WESTBROOK,J. I. & BRAITHWAITE,J. 2011b. How andwhy are communitiesof

practice establishedinthe healthcare sector?A systematicreviewof the literature.

BMC HealthServices Research, 11, 1.

107. RICHIE,J. & LEWIS, J. 2003. QualitativeResearch Practice: A guidefor social

science studentsand researchers.

108. [Online].DelhiandLondon:Sage publisher.Available:

https://mthoyibi.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/qualitative-research-practice_a-

guide-for-social-science-students-and-researchers_jane-ritchie-and-jane-lewis-

eds_20031.pdf [Accessed].

109. RIKARD-BELL,G., DONNELLY,N.& WARD,J. 2003. Preventive dentistry:what

do Australianpatientsendorseandrecall of smokingcessationadvice bytheir

dentists? BrDent J, 194, 159-64; discussion150.

110. RODRÍGUEZ, O. M., CICESE, MARTÍNEZ, A.I., CICESE,FAVELA,J.,CICESE,

VIZCAÍNO,A.,UNIVERSITYOFCASTILLA-LA MANCHA,E.S.D. I., PIATTINI,M.&

UNIVERSITYOF CASTILLA-LA MANCHA,E.S. D. I. UnderstandingandSupporting

KnowledgeFlowsinaCommunityof Software Developers. CRIWG,2004. Springer

BerlinHeidelberg,52-66.

111. ROSSEEL, J.P., JACOBS,J.E., HILBERINK,S.R., MAASSEN,I.M., ALLARD, R.

H., PLASSCHAERT,A.J.& GROL, R. P.2009. What determinesthe provisionof

smokingcessationadvice andcounsellingbydental care teams? BrDent J, 206, E13;

discussion376-7.

112. ROSSEEL, J.P., JACOBS,J.E., HILBERINK,S.R., MAASSEN,I.M., SEGAAR, D.,

PLASSCHAERT,A.J. & GROL, R. P. 2011. Experiencedbarriersandfacilitatorsfor

integratingsmokingcessationadviceandsupportintodailydental practice.A short

report. Br Dent J, 210, E10.

113. SACKETT,D. L., ROSENBERG,W. M., GRAY, J.A.,HAYNES, R. B. &

RICHARDSON,W.S. 1996. Evidence basedmedicine:whatitisandwhat itisn't. BMJ,

312, 71-2.

114. SANDELOWSKI,M.,DEPARTMENT OF WOMEN'S ANDCHILDREN'S HEALTH,

S. O. N.,UNIVERSITYOF NORTHCAROLINA ATCHAPEL HILL & UNIVERSITYOF NORTH

CAROLINA ATCHAPEL HILL, C. H., CHAPELHILL, NC 27599‐7460 2007. Sample size in

qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18, 179-183.

115. SCHNOLL,R. A.,GOELZ, P.M., VELUZ-WILKINS,A.,BLAZEKOVIC,S.,POWERS,

L., LEONE, F.T., GARITI,P., WILEYTO, E. P.& HITSMAN,B. 2015. Long-termnicotine

replacementtherapy:arandomizedclinicaltrial. JAMA Intern Med, 175,504-11.

116. SENGE, P.1990. The Leader’sNew Work: Building Learning Organizations

[Online].Available: http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-leaders-new-work-

building-learning-organizations/[AccessedJuly2016].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-84-320.jpg)

![85

117. SEVERSON,H.H., KLEIN,K., LICHTENSEIN,E.,KAUFMAN,N.& ORLEANS,C.T.

2005. Smokelesstobaccouse amongprofessional baseball players:surveyresults,

1998 to 2003.

118. SHERWIN,G. B., NGUYEN, D., FRIEDMAN,Y. & WOLFF, M. S. 2013. The

relationshipbetweensmokingandperiodontaldisease.Review of literature and

case report. N Y StateDent J, 79, 52-7.

119. SILAGY,C., MANT, D.,FOWLER, G. & LANCASTER,T.2000. Nicotine

replacementtherapyforsmokingcessation. CochraneDatabaseSystRev,Cd000146.

120. SINHA,D. N.,RIZWAN,S.,ARYAL,K. K.,KARKI,K.B., ZAMAN,M. M. &

GUPTA, P.C. 2015. Trendsof SmokelessTobaccouse amongAdults(Aged15-49

Years) inBangladesh,IndiaandNepal. Asian PacJCancerPrev, 16, 6561-8.

121. SMITH, A. L., CARTER,S. M., DUNLOP, S.M., FREEMAN,B. & CHAPMAN,S.

2015a. The viewsandexperiencesof smokerswhoquitsmokingunassisted.A

systematicreviewof the qualitative evidence. PLoSOne, 10, e0127144.

122. SMITH, A. L., CHAPMAN,S.& DUNLOP, S.M. 2015b. What do we know

aboutunassistedsmokingcessationinAustralia?A systematicreview,2005-2012.

Tob Control, 24, 18-27.

123. SOFIA FINK,A.2000. A role of the researcherin the Qualitativeresearch

process:A potentialbarrier to archiving qualitativeData. [Online].Available:

http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1021/2201

[Accessed].

124. SOOD,P.,NARANG,R.,SWATHI,V.,MITTAL, L., JHA,K.& GUPTA, A.2014.

Dental patient'sknowledgeandperceptionsaboutthe effectsof smokingandrole of

dentistsinsmokingcessationactivities. EurJDent, 8, 216-23.

125. STACEY, F.,HEASMAN,P. A.,HEASMAN,L., HEPBURN,S., MCCRACKEN,G. I.

& PRESHAW,P. M. 2006. Smokingcessationasa dental intervention--viewsof the

profession. BrDentJ, 201, 109-13; discussion99.

126. STEAD, L. F.,BUITRAGO, D., PRECIADO,N.,SANCHEZ,G.,HARTMANN-

BOYCE, J. & LANCASTER,T.2013. Physicianadvice forsmokingcessation. Cochrane

DatabaseSystRev, 5, Cd000165.

127. STEAD, L. F.,HARTMANN‐BOYCE,J.,PERERA,R. & LANCASTER,T. 2015.

Telephone counsellingforsmokingcessation.

128. STEAD, L. F. & LANCASTER,T.2015. Group behaviourtherapyprogrammes

for smokingcessation.

129. STENMARK,D. 2001. The Relationship between information and knowledge.

[Online].Available:

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.21.965&rep=rep1&type

=pdf [Accessed].

130. STEWART, K.,GILL, P., CHADWICK,B.& TREASURE, E. 2008. Qualitative

researchindentistry. British Dental Journal, 204, 235-239.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-85-320.jpg)

![86

131. STRAUSS,A. & CORBIN,J.1998. Basics of qualitativeresearch:Technique

and ProcedureforDeveloping grounded theory [Online].Available: http://stiba-

malang.com/uploadbank/pustaka/RM/BASICOFQUALITATIVERESEARCH.pdf

[Accessed].

132. SUCCAR,C. T., HARDIGAN,P.C., FLEISHER,J. M. & GODEL, J. H. 2011. Survey

of tobaccocontrol among Floridadentists. JCommunity Health, 36, 211-8.

133. THORNE, S.2000. Data analysisin Qualitative research [Online].Available:

http://m.ebn.bmj.com/content/3/3/68.full [Accessed].

134. TRUST, B. N. 2016. BartsHealth - Forour dentalpatients [Online].Available:

http://bartshealth.nhs.uk/our-services/services-a-z/d/dental/for-patients/

[Accessed].

135. VANGELI,E.,STAPLETON,J.,SMIT, E. S.,BORLAND,R. & WEST, R. 2011.

Predictorsof attemptstostop smokingandtheir successinadultgeneral population

samples:asystematicreview. Addiction, 106,2110-21.

136. VIDRINE,J.I.,SHETE, S.,CAO,Y., GREISINGER,A., HARMONSON,P.,SHARP,

B., MILES, L., ZBIKOWSKI,S.M. & WETTER, D. W. 2013. Ask-Advise-Connect:anew

approach to smokingtreatmentdeliveryinhealthcare settings. JAMA Intern Med,

173, 458-64.

137. VIDYASAGARAN,A.L.,SIDDIQI,K.& KANAAN,M.2016. Use of smokeless

tobacco and riskof cardiovasculardisease:A systematicreviewandmeta-analysis.

Eur J Prev Cardiol.

138. VIRTANEN,S.E.,ZEEBARI, Z.,ROHYO, I. & GALANTI,M. R. 2015. Evaluation

of a brief counselingfortobaccocessationindental clinicsamongSwedishsmokers

and snususers.A clusterrandomizedcontrolledtrial (the FRITTstudy). Prev Med,

70, 26-32.

139. WALSH, M. M., BELEK, M., PRAKASH,P.,GRIMES,B., HECKMAN,B.,

KAUFMAN,N.,MECKSTROTH, R., KAVANAGH,C.,MURRAY, J.,WEINTRAUB, J.A.,

SILVERSTEIN,S.& GANSKY,S. A.2012. The effectof trainingonthe use of tobacco-

use cessationguidelinesindental settings. TheJournalof theAmerican Dental

Association, 143, 602-613.

140. WANG,D., CONNOCK,M.,BARTON,P.,FRY-SMITH,A., AVEYARD,P.&

MOORE, D. 2008. 'Cut downto quit'withnicotine replacementtherapiesinsmoking

cessation:asystematicreview of effectivenessandeconomicanalysis. Health

Technol Assess, 12, iii-iv,ix-xi,1-135.

141. WATT, R. G., MCGLONE, P.,DYKES, J. & SMITH, M. 2004. Barriers limiting

dentists'active involvementinsmokingcessation. OralHealth Prev Dent, 2, 95-102.

142. WENGER, E. 1998. How we learn:communitiesof practice-the socialfabric

of learningorganisation. TheHealthcareForumJournal.

143. WENGER, E., MCDERMOTT, R. & SNYDER, W. 2002. CultivatingCommunities

of Practice:A Guide to ManagingKnowledge.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-86-320.jpg)

![87

144. WHITE, M., BUSH, J.,KAI,J.,BHOPAL,R. & RANKIN,J.2006. Quittingsmoking

and experience of smokingcessationinterventionsamongUKBangladeshi and

Pakistani adults:the viewsof communitymembersandhealthprofessionals. J

Epidemiol CommunityHealth.

145. WHO. 2015. Dataand statistics [Online].WorldHealthOrganization.

Available:http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-

prevention/tobacco/data-and-statistics[AccessedDecember2015].

146. WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION.2005. The Rolesof Health Professionalin

tobacco control[Online].Geneva:WHO.Available:

http://www.who.int/tobacco/resources/publications/wntd/2005/bookletfinal_20ap

ril.pdf [AccessedJuly2016].

147. WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION 2013. WHO | WHO report onthe global

tobacco epidemic,2011. WHO.

148. WRIGHT, D. 2016. Health Systems. [Online].Available:

http://qmplus.qmul.ac.uk/pluginfile.php/702270/mod_resource/content/0/Lecture

HealthSystems2016.pdf [Accessed].

149. WU, F., PARVEZ,F.,ISLAM,T., AHMED, A., RAKIBUZ-ZAMAN,M.,HASAN,R.,

ARGOS,M., LEVY, D., SARWAR,G., AHSAN,H.& CHEN, Y. 2015. Betel quiduse and

mortalityinBangladesh:acohortstudy. Bull World Health Organ.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-87-320.jpg)

![95

Appendix 6 – Topic guide

Knowledge sharingin professional communitiesofpractice and its role in tobacco

cessationin hospital.

Explanation ofwhat is involvedandconfirmation of consent.

Confirmconsentverballyandchecktheyare OK with itbeingrecorded.

[TURN ON THE RECORDER]

Topic guide

Dentistdemographics:

1. Whendidyou qualifyasa dentist?

2. How longhave youworkedinthe practice where youare now?

3. Can youtell me a little aboutyourpractice?

a. How are you remunerated –throughthe NHS,privatelyora mixture?

b. Can youtell me aboutany dentistsanddental care professionalswhowork

withyou?

4. Can youtell me a little aboutyourcareere.g.time inhospitals,differentpractices

5. Can youtell me aboutany dental professional groupsorcommunitiesoutside of the

dental practice thatyou belongto?Couldbe “real”or “virtual”.

Checkingunderstandingof conceptof knowledge for thisinterview:

1. We’re goingto talkaboutknowledge inthissection.

2. Are you OKwiththe descriptionsof knowledgethatwe gave inthe information

sheet?

a. Scientificknowledge

b. Experiential

c. Administrative

d. Regulation

e. Social or sharedknowledge

f. Practical – howto do things

g. Knowledgeof the contextinwhichyouwork

h. Knowledgeof the healthsystemswithinwhichyou work](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-95-320.jpg)

![97

Sharing effective tobaccouse cessationwith othercolleagues

1. NowI wouldlike youtoimagine thatyouwouldlike tobe able tohelpcolleagues

use thisnewapproach.You wouldlike tohelpthemenactitintheirownpractices.

How wouldyougoabout doingthis?

Probingquestions:

Who wouldyoushare itwith?

How wouldyoushare it?

How wouldyouhelpthemtouse it?E.g. wouldyougo lookat how it couldwork

intheirsetting?

What barriersdo youthinktheymighthave tothis?

How mightyoutry to overcome these?

Who outside of the dental teamcouldhelptospreadyoureffectivepractice?

E.g. local commissioners,oral healthcharities,GPs,healthworkers

Ending

Thank themforparticipating

[TURN OFF THE RECORDER]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dfc6779e-4828-4023-bc1e-944e1439f772-170104092835/85/Ibrahim-Thesis-97-320.jpg)