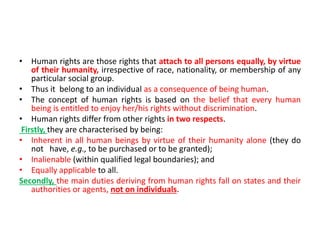

This document provides an overview of the key concepts and historical development of human rights law. It discusses how human rights are inherent to all humans, regardless of attributes. The three main sources of international human rights law are identified as international conventions, customary international law, and general principles of law. The document then summarizes the major milestones in the development of the international human rights system, including the UN Charter, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

![• The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, as

amended by the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, is

the most important international instrument protecting the rights

of refugees.

• It says,Refuge is [A]ny person who owing to well-founded fear of

being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality,

membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is

outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such

fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or

who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his

former habitual residence, is unable or, owing to such fear, is

unwilling to return to it.

• In addition to international and regional refugee conventions,

international human rights law and international humanitarian law

play a significant role in guaranteeing international protection of

refugees.E.g ICCPR(7),CAT(3),CRC,Fourt Geneve Convention(44)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/humanrightslaw1-notes-mekele-240119182704-b4acd580/85/HUman-Rights-Law-1-Notes-mekele-pptx-74-320.jpg)