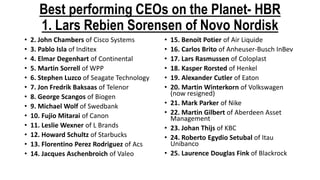

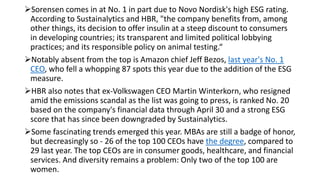

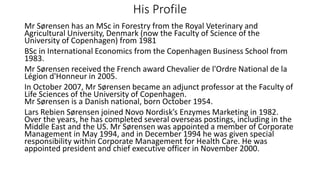

1. Lars Sørensen, CEO of Novo Nordisk, was ranked the #1 CEO in the world by HBR based on his company's strong financial performance and high ESG rating.

2. Sørensen believes Novo Nordisk's success is due to its narrow focus on diabetes treatment, where it has deep expertise, rather than diversifying into new areas.

3. If Novo Nordisk cures diabetes, Sørensen says they will be proud to put themselves out of business, though curing the disease remains a long term goal.