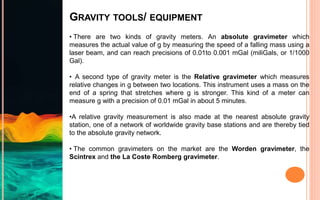

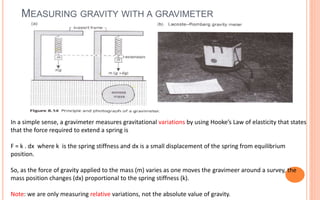

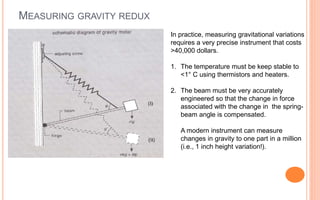

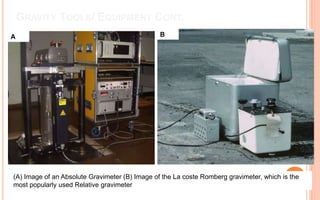

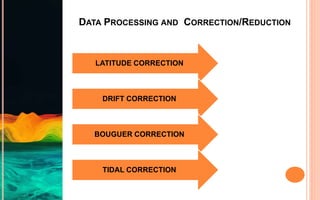

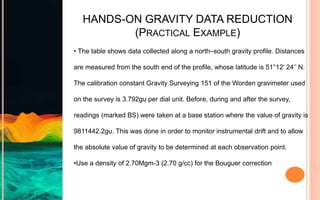

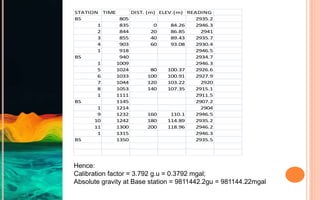

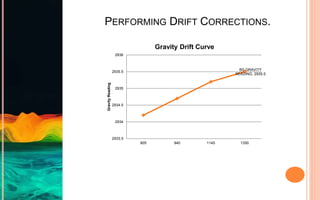

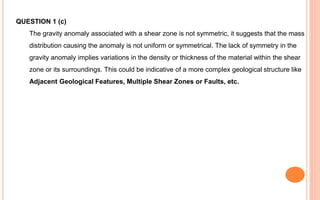

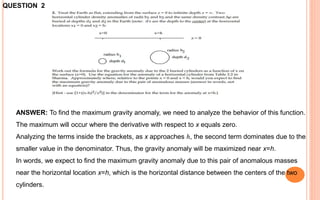

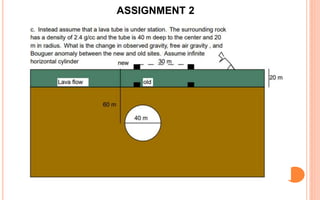

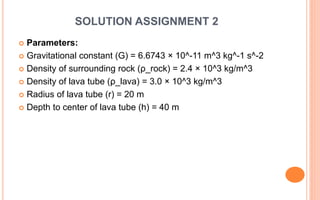

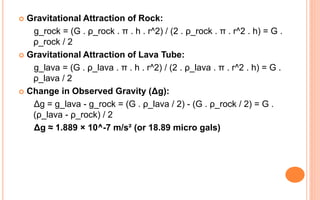

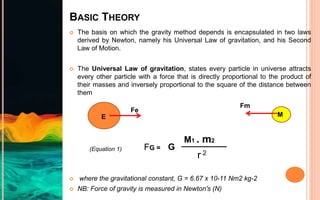

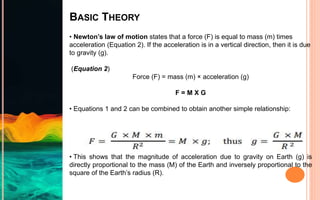

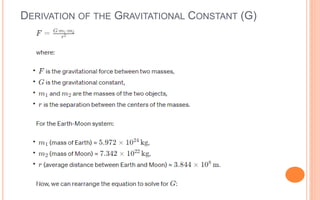

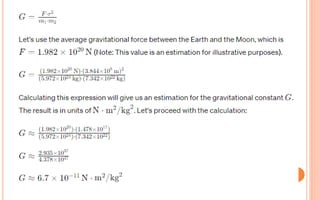

The document discusses the gravity method used for measuring the Earth's gravitational field to identify subsurface density variations, emphasizing its applications in various fields such as geological studies, hydrocarbon exploration, and archaeological investigations. It explains the fundamental theoretical concepts behind gravity measurements, including the laws of gravitation, gravitational and inertial mass, and highlights the use of different types of gravimeters for data acquisition. Additionally, it covers the various corrections needed for accurate gravity measurements, including latitude and drift corrections.

![• The normal value of g at the Earth’s surface is 980 cm/s2 . However, In

honour of Galileo, the c.g.s. unit of acceleration due to gravity (1 cm/s2 ) is

Gal.

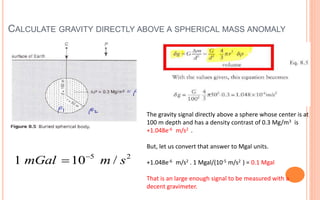

•Furthermore, Modern gravity meters (gravimeters) can measure extremely

small variations in acceleration due to gravity, typically 1 part in 109 . The

sensitivity of modern instruments is about ten parts per million. Such small

numbers have resulted in sub-units being used such as the:

milliGal (1 mGal = 10-3 Gal);

microGal (1 μGal = 10-6 Gal); and

1 gravity unit = 1 g.u. =0.1 mGal [10 gu =1 mGal]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ugwuadathankgodglgl831gravitymethod-240612104053-8138b235/85/GLG-831-GEOPHYSICS_GRAVITY-METHOD-pptx-9-320.jpg)