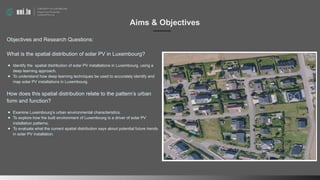

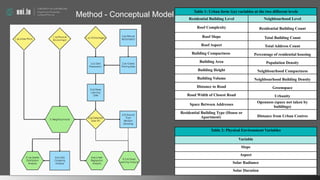

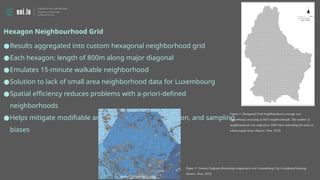

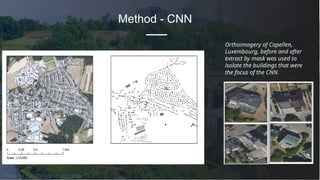

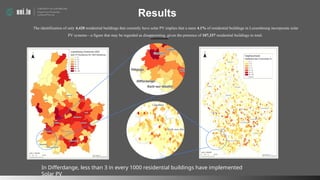

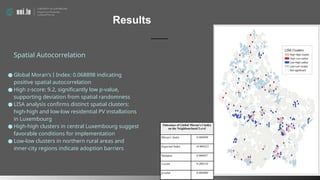

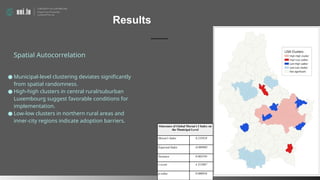

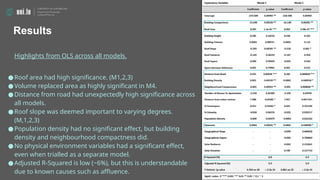

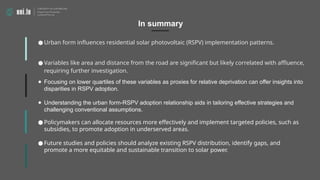

The study investigates the spatial distribution and implementation of residential solar photovoltaics (RSPV) in Luxembourg, utilizing deep learning techniques and spatial regression analysis. Results indicate that only 4.1% of residential buildings currently incorporate solar PV systems, with clusters revealing favorable conditions in central areas and barriers in rural and inner-city regions. The findings highlight the influence of urban form on RSPV adoption and suggest targeted policy interventions to promote solar power in underserved areas.