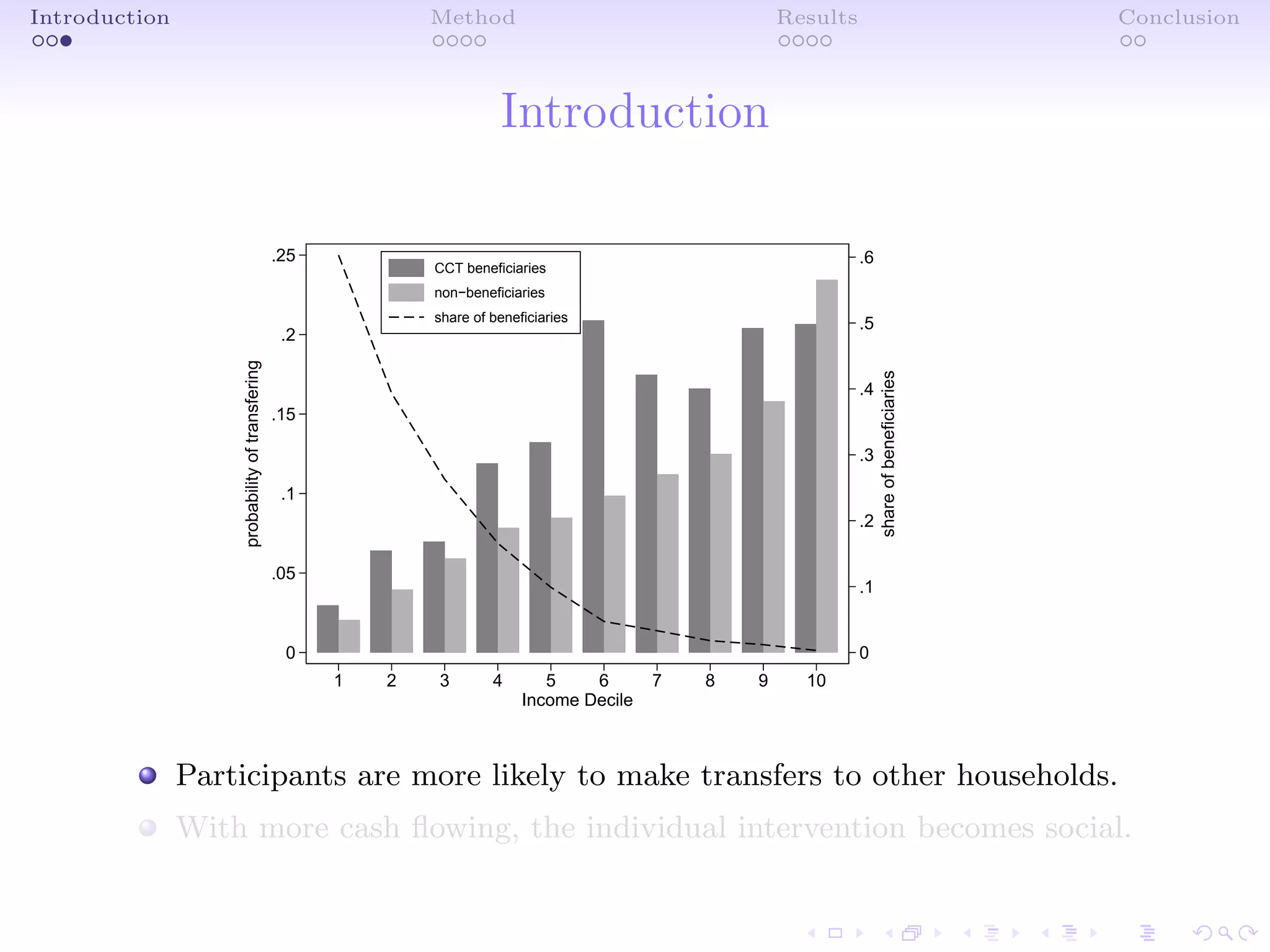

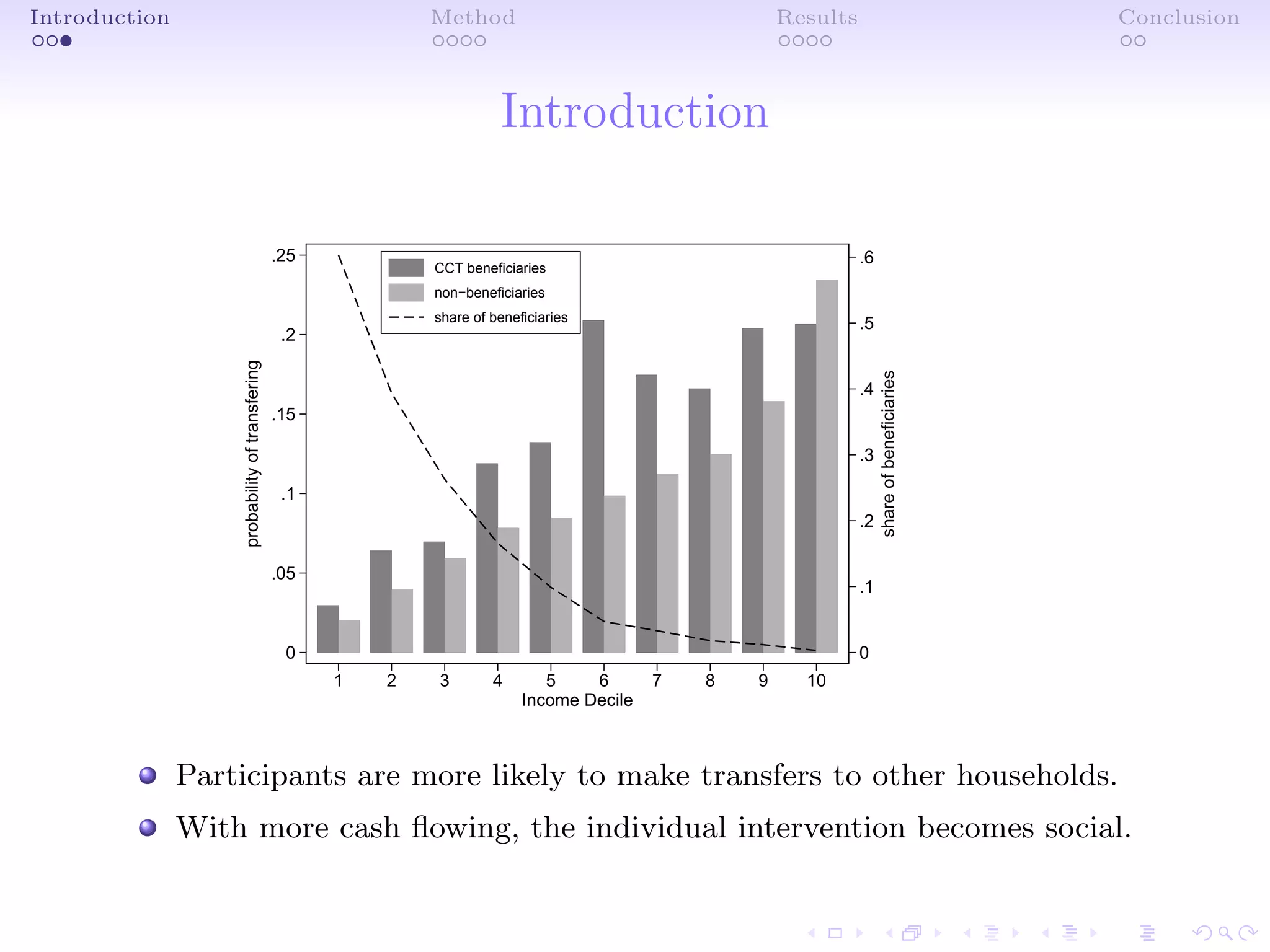

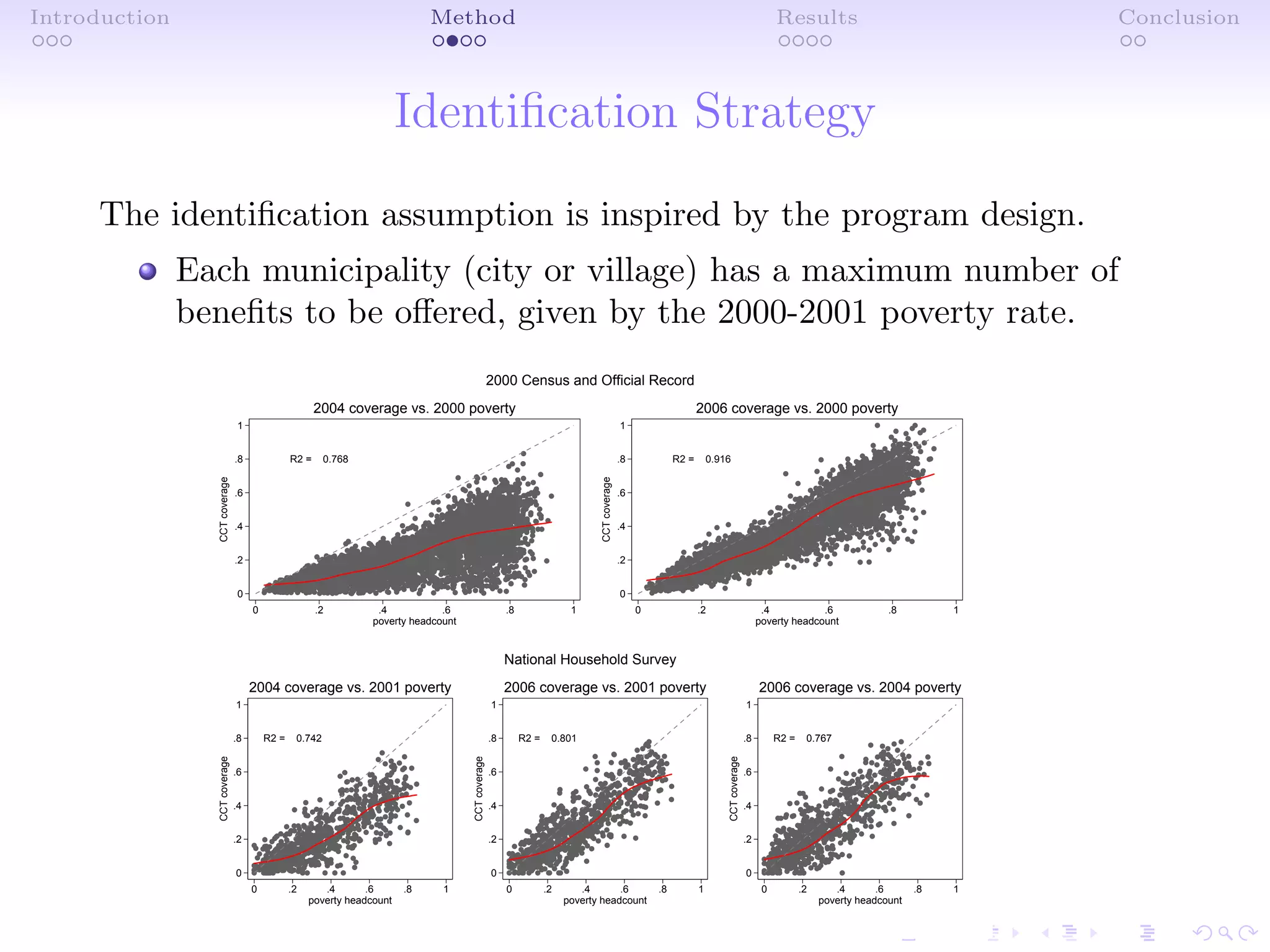

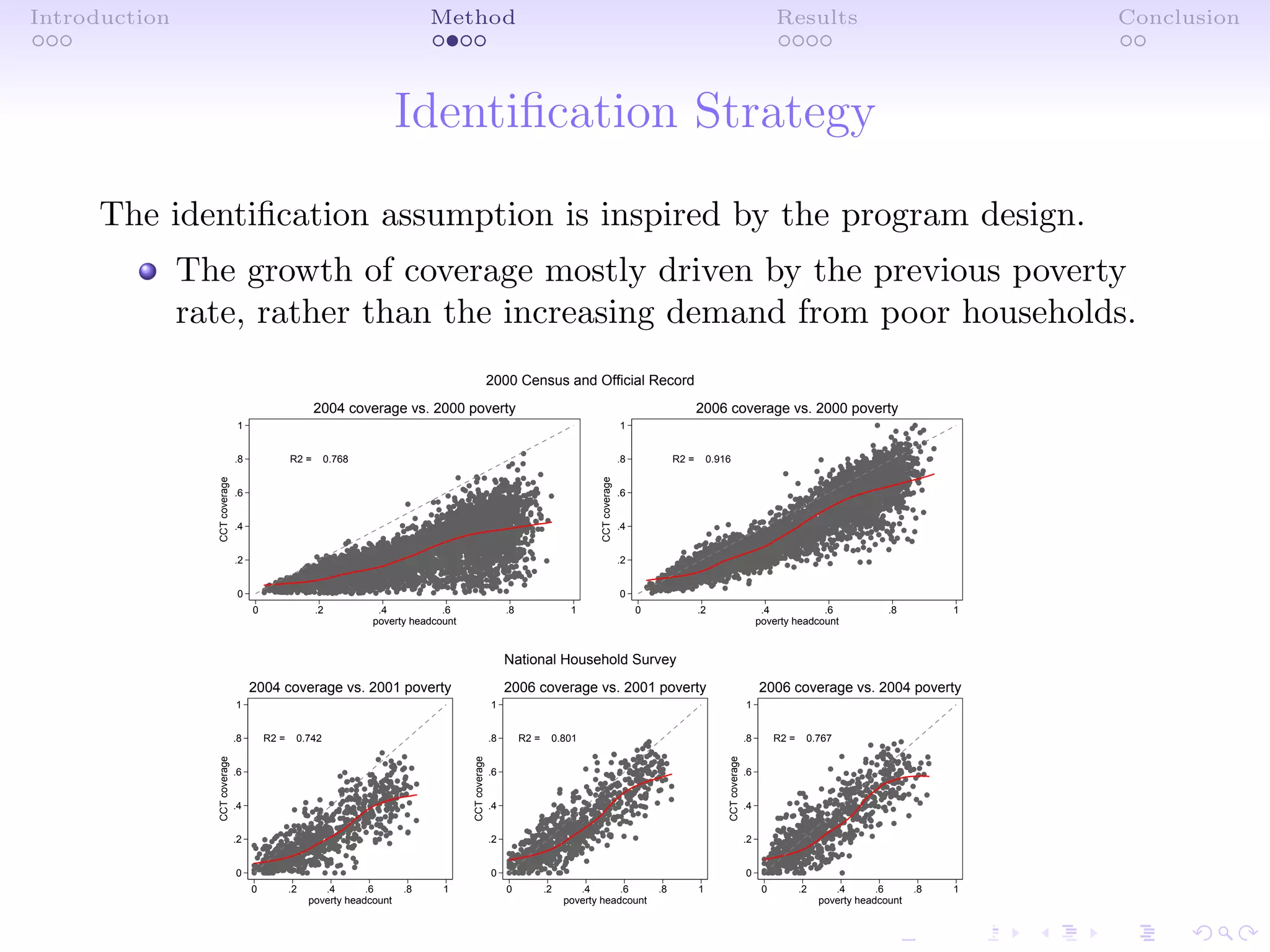

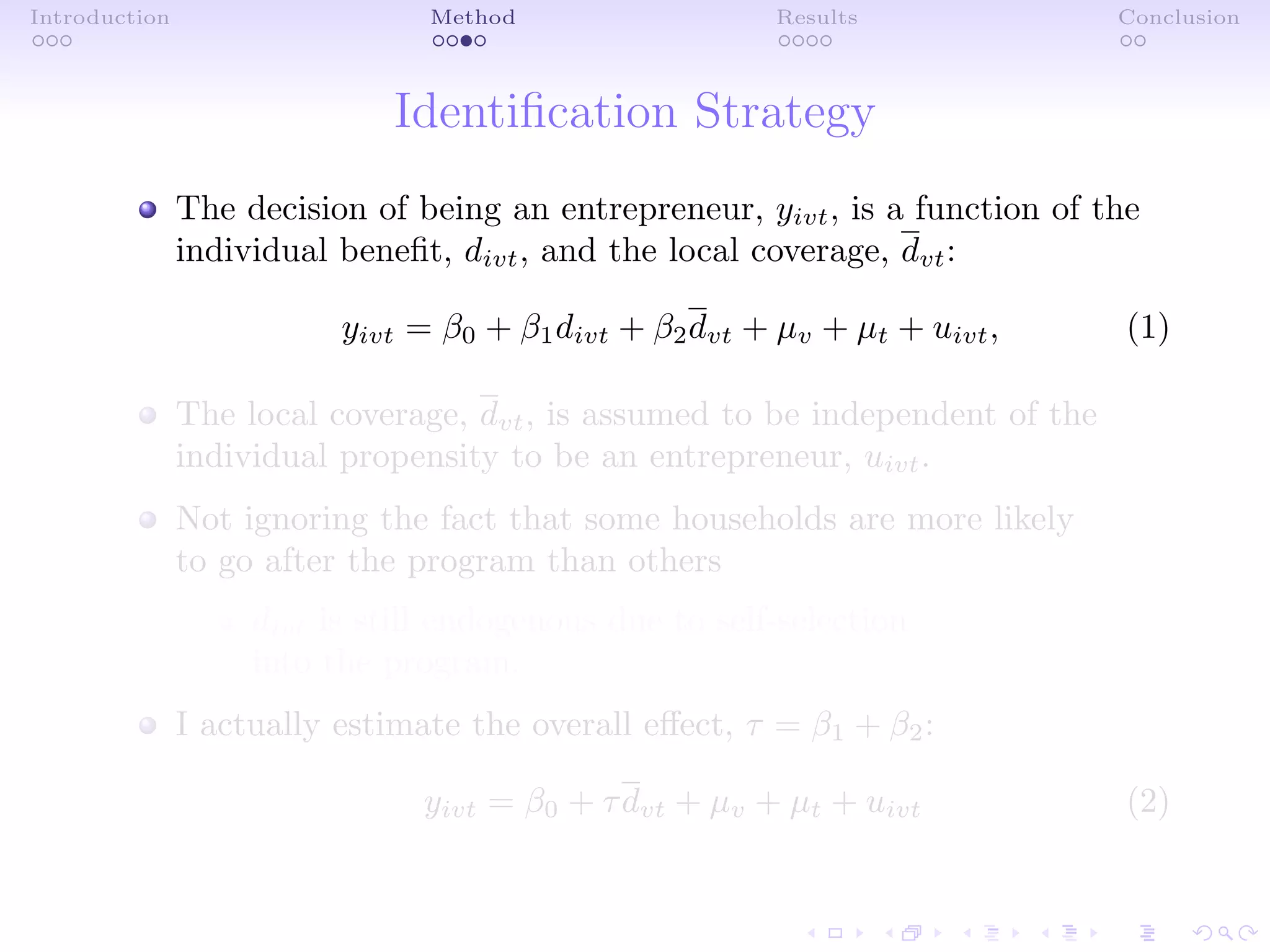

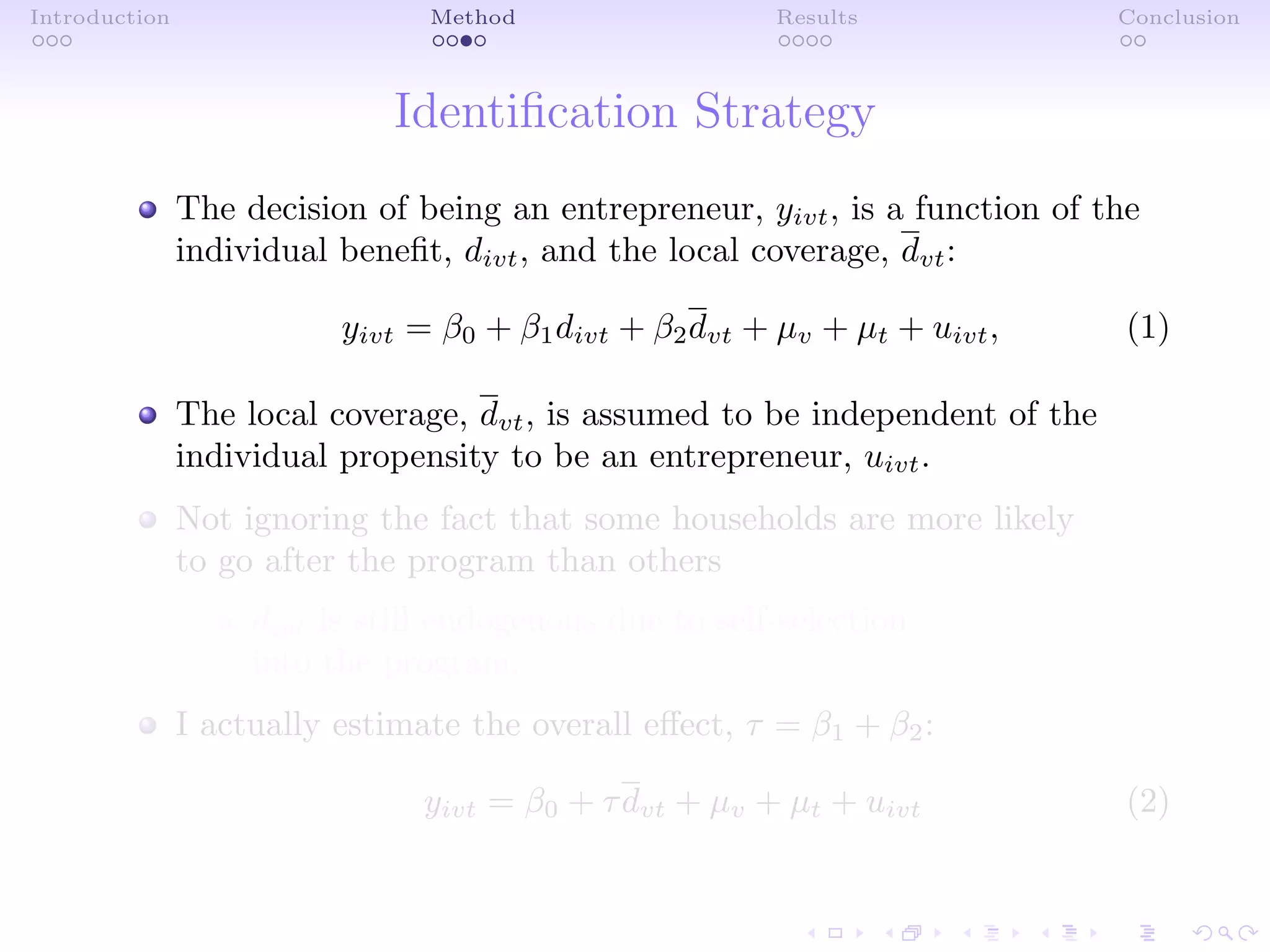

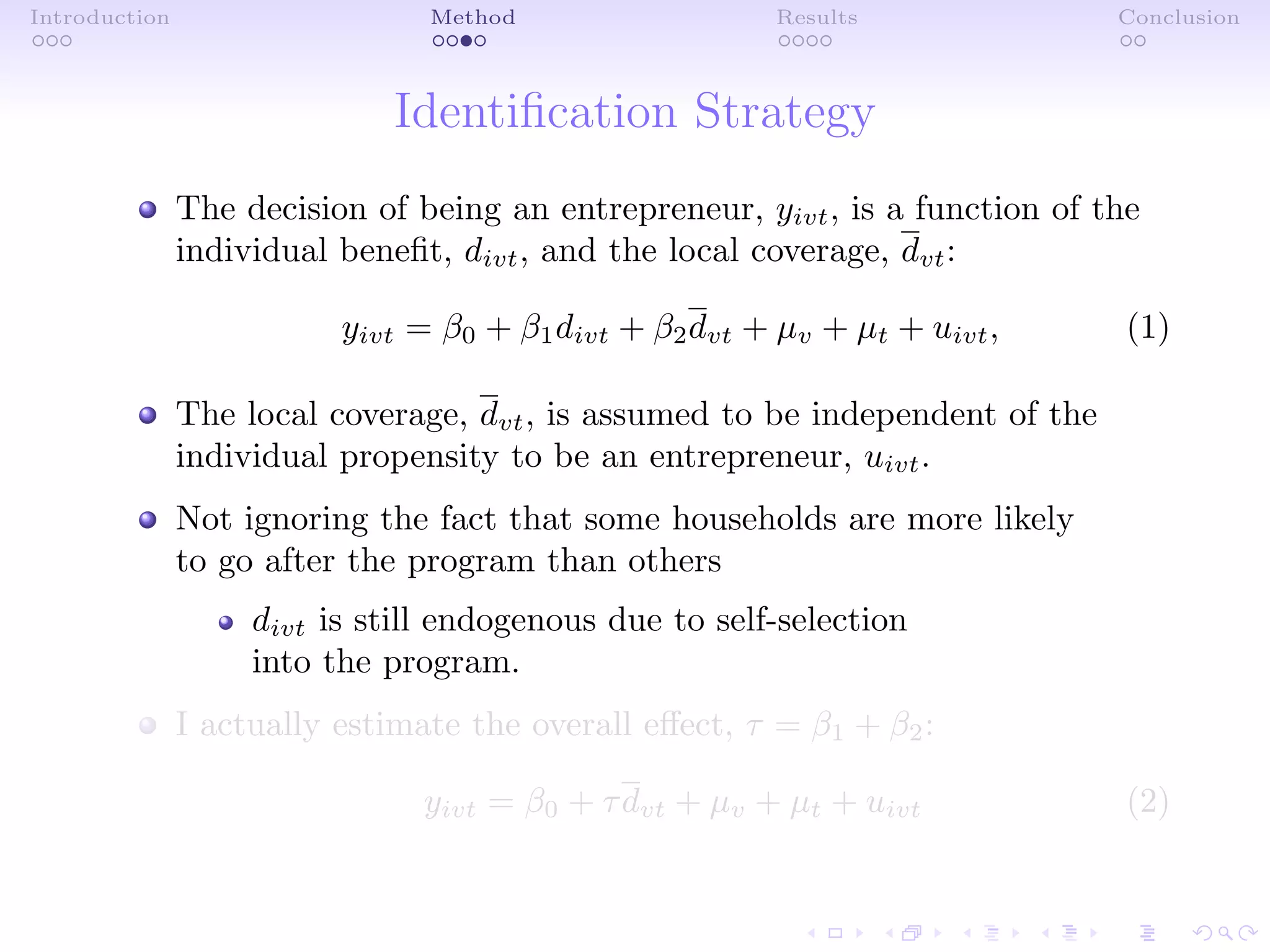

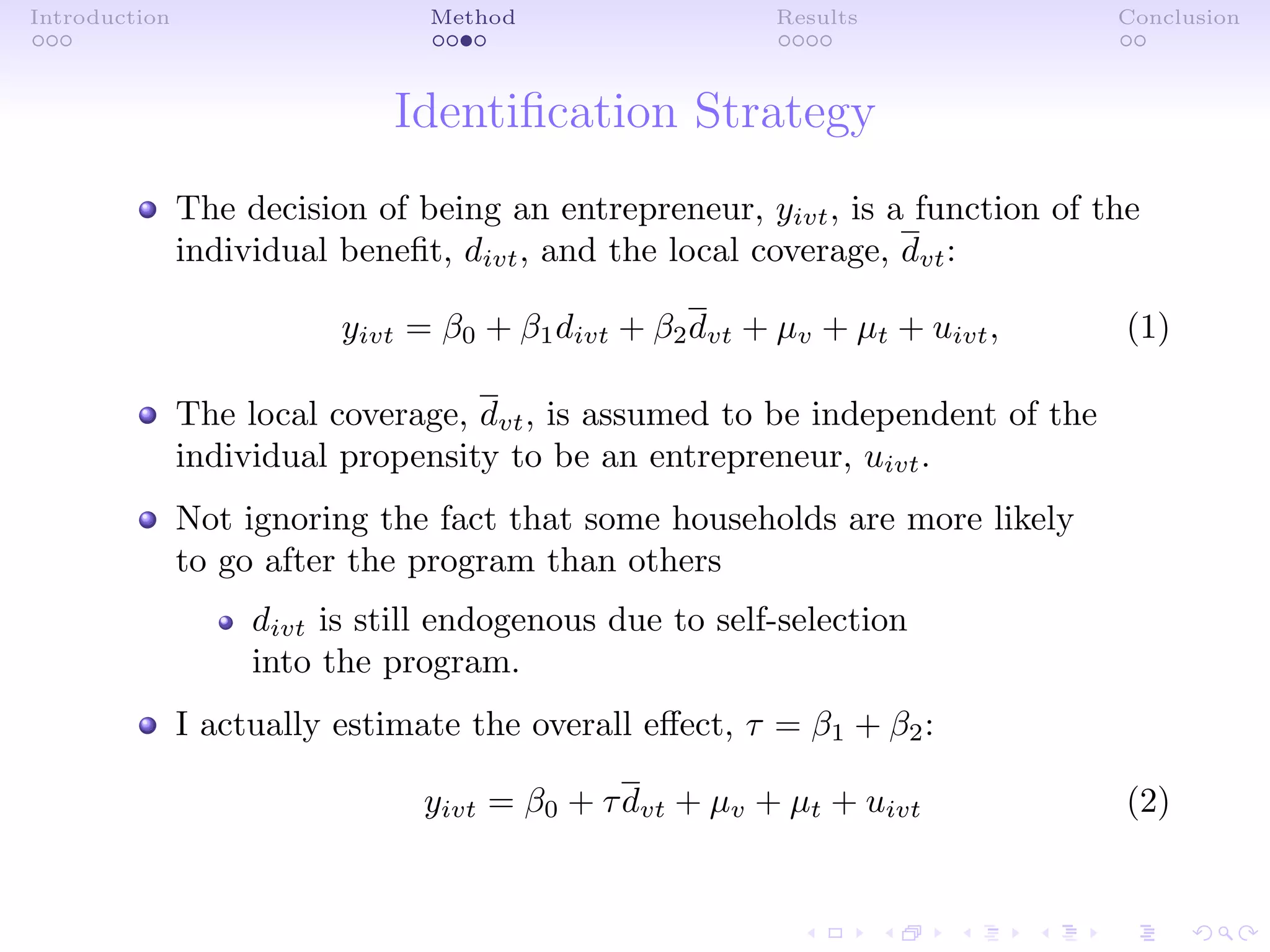

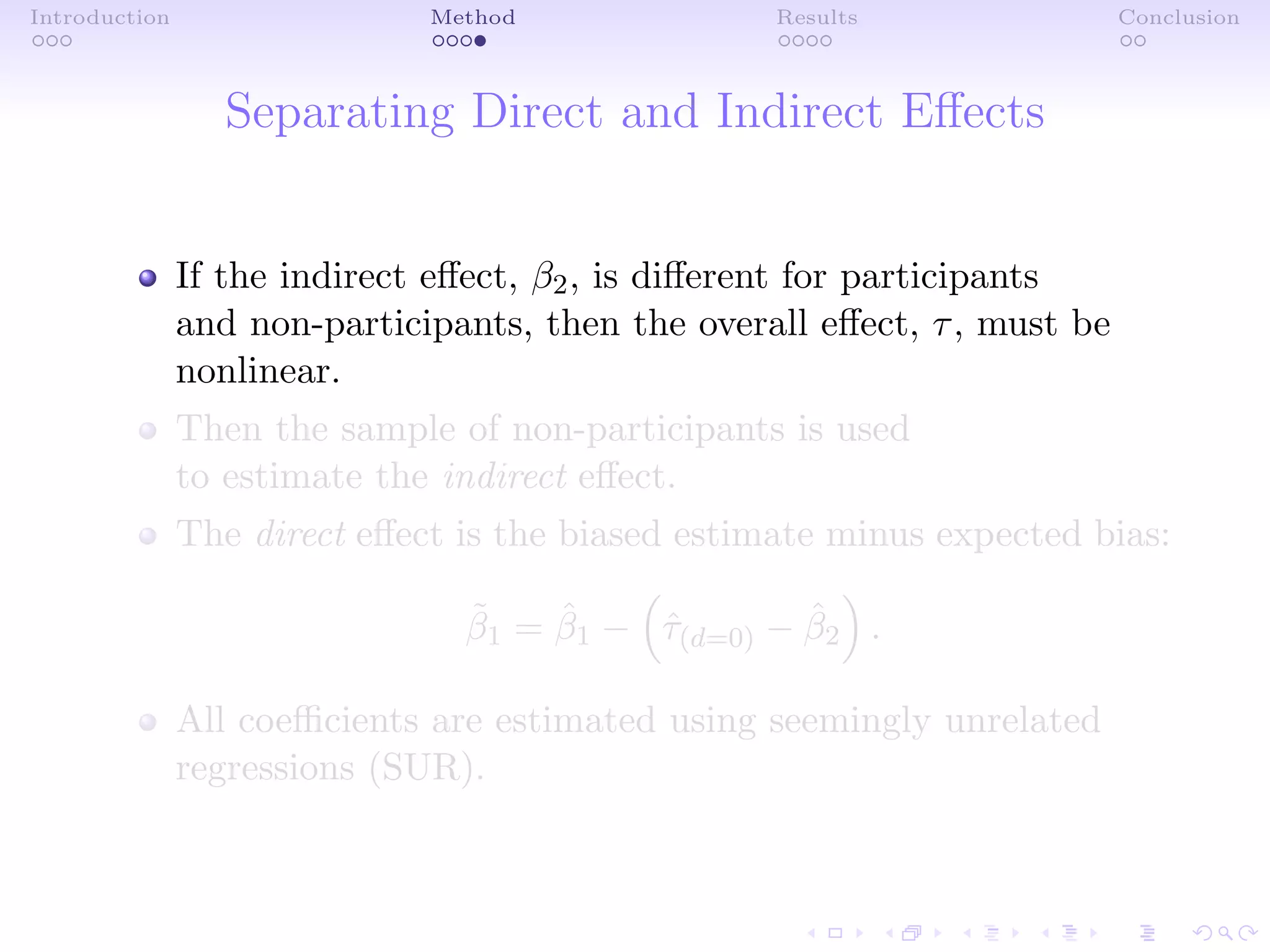

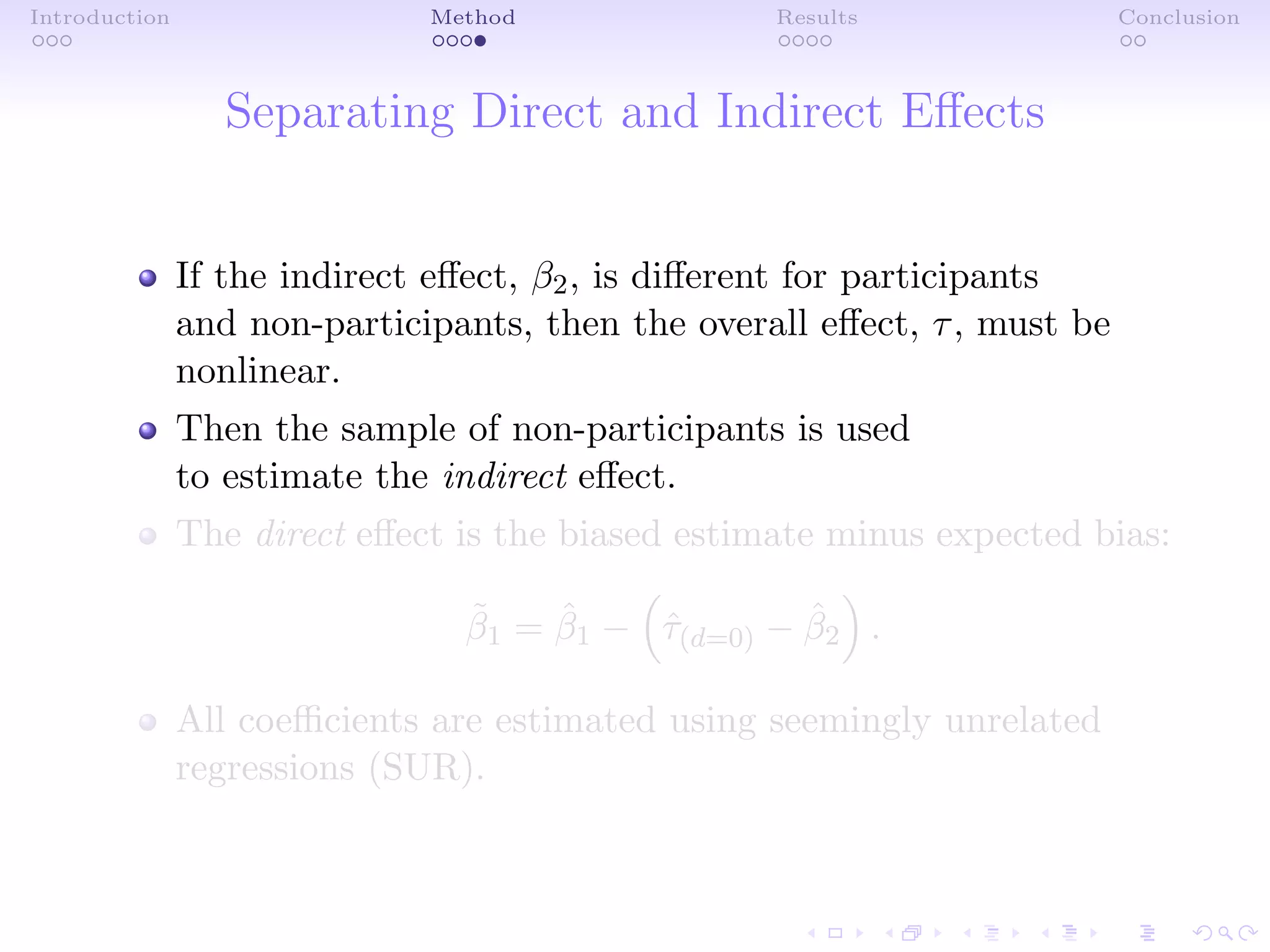

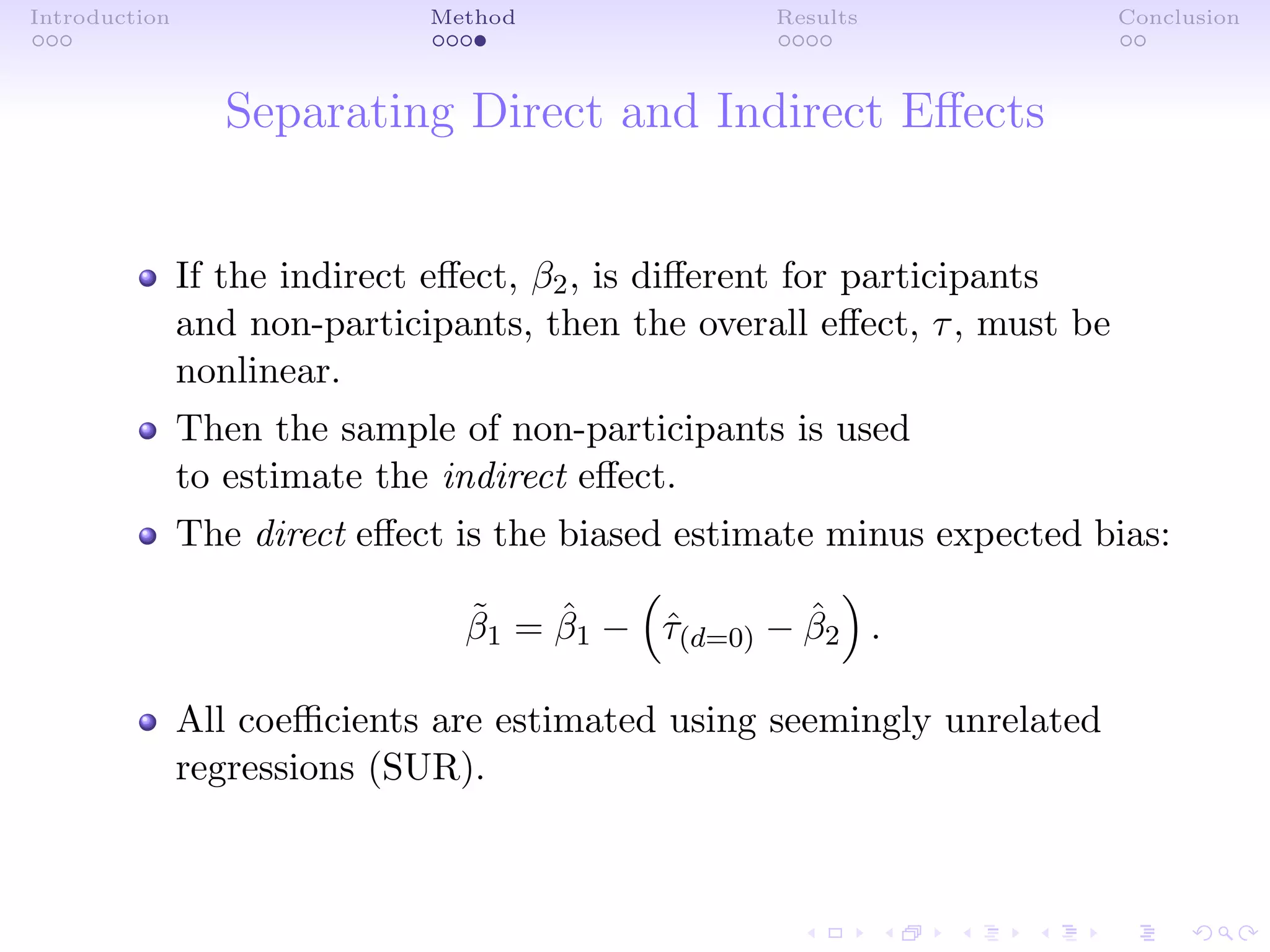

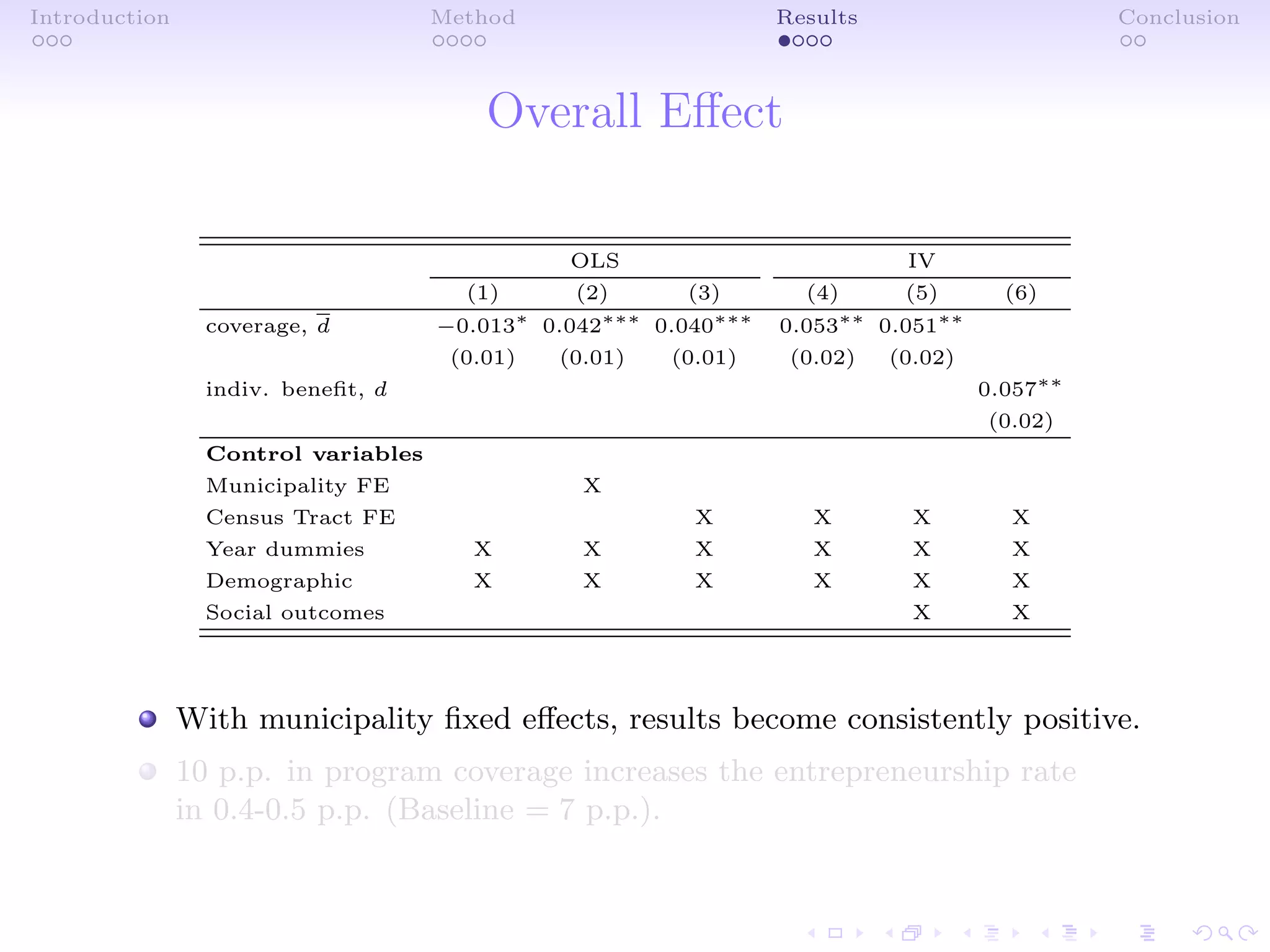

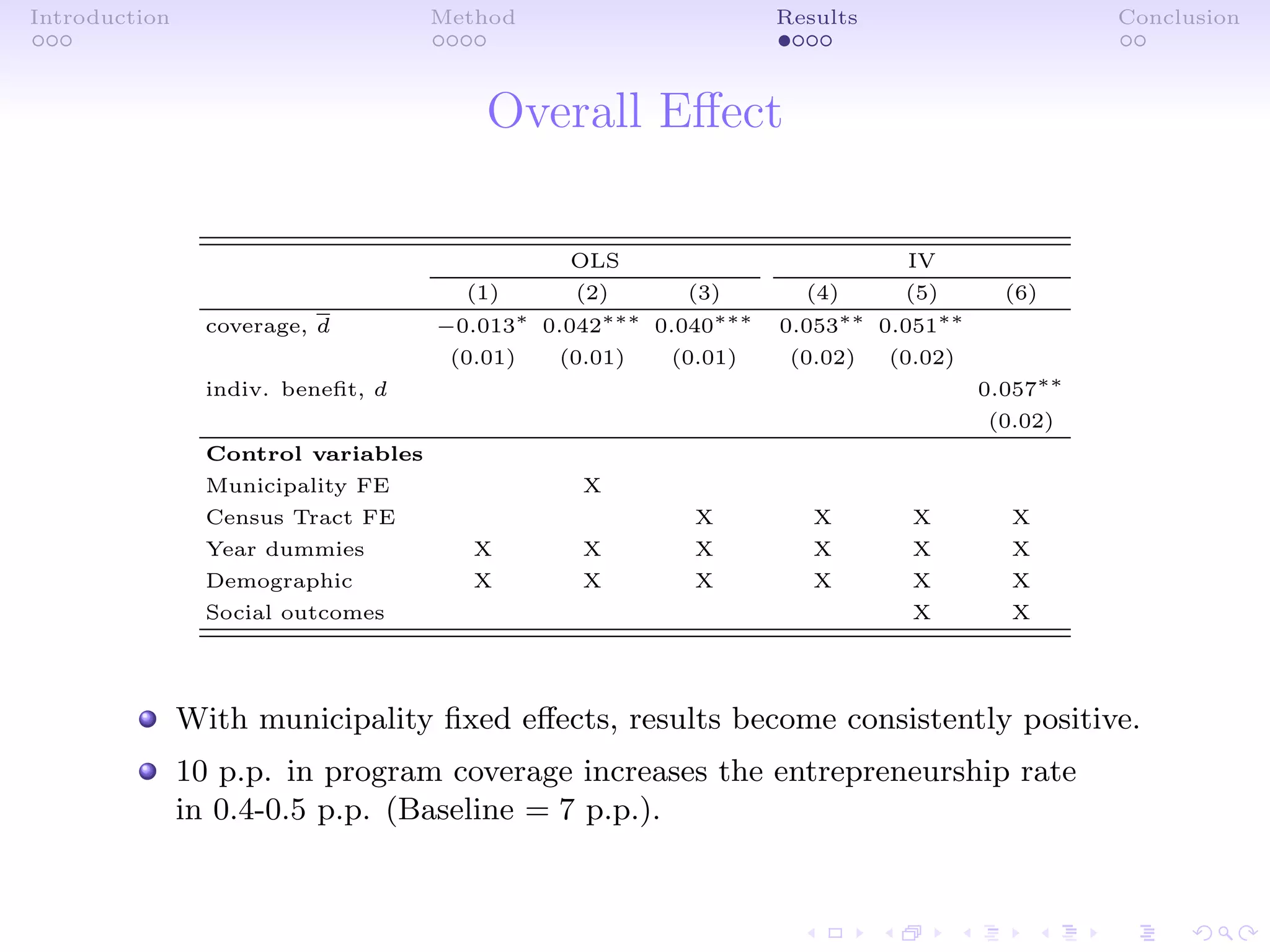

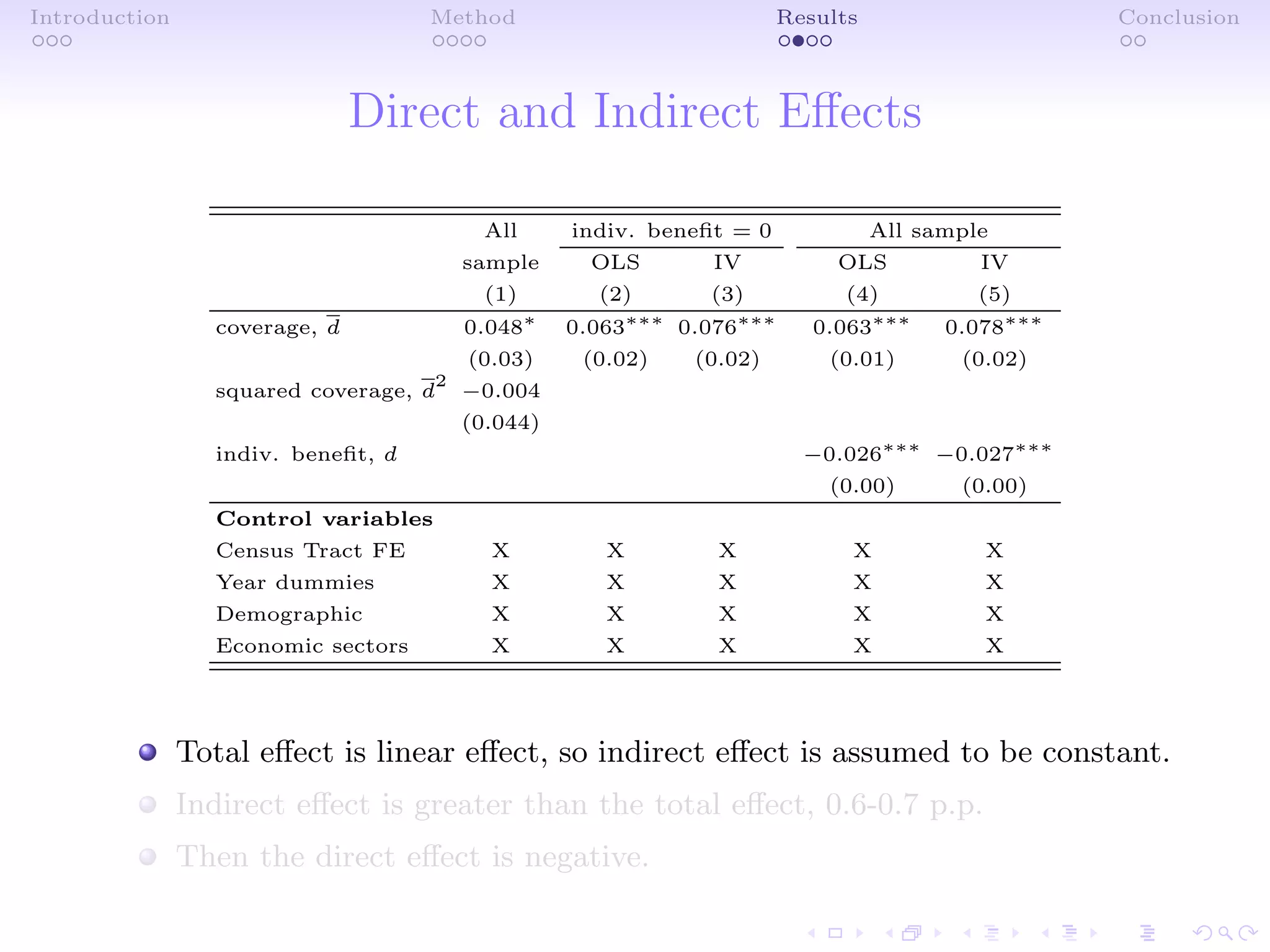

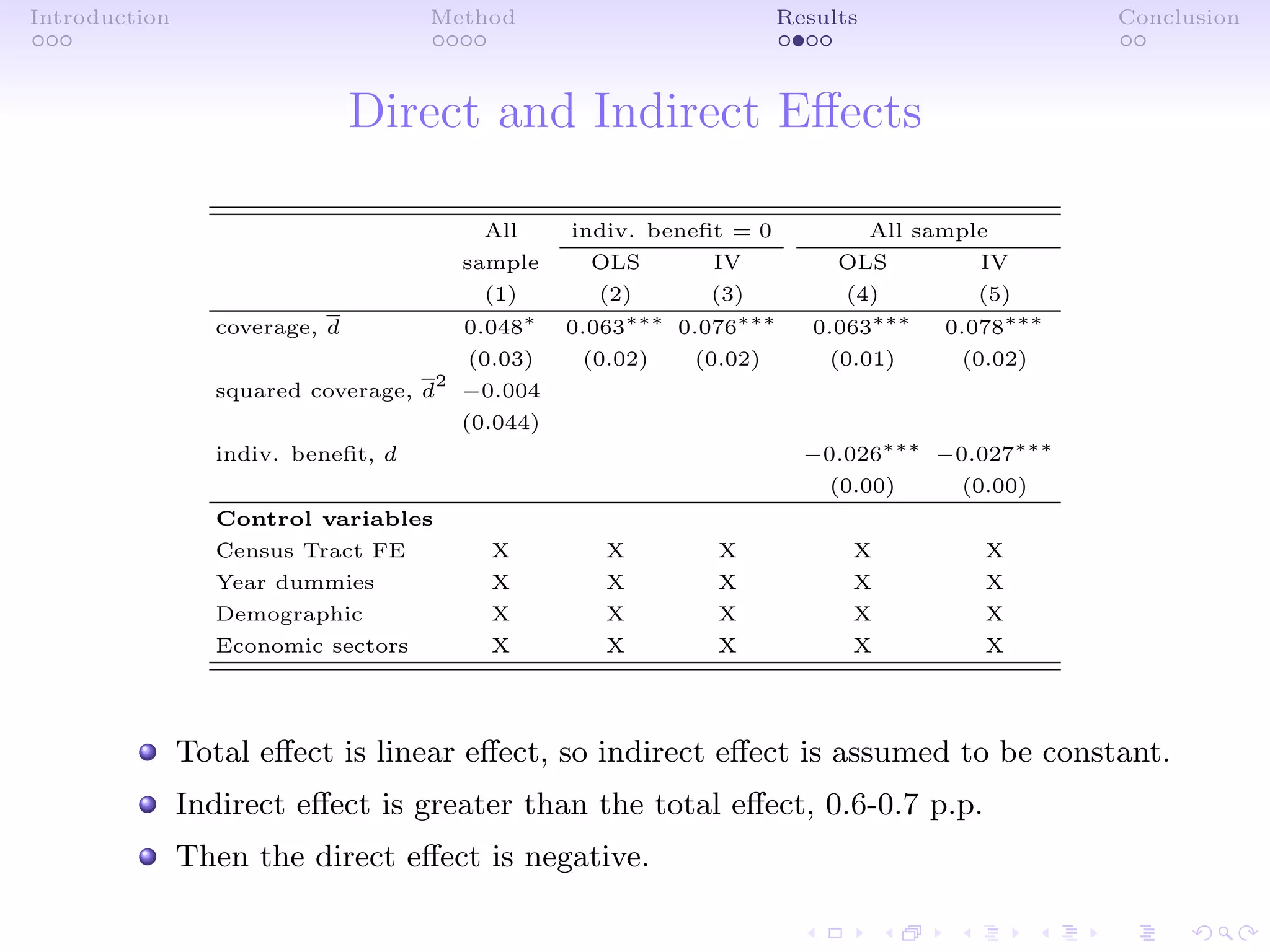

This document examines the impact of Brazil's Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer program on entrepreneurship in low-educated households. It highlights both direct effects on participants and indirect social effects, such as increased aggregate demand and informal credit availability. The findings indicate that greater program coverage correlates with increased entrepreneurship rates among participants.