The document provides context and summary for the medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It introduces the poem's setting in King Arthur's court during Christmas celebrations. It describes how a mysterious green knight arrives and challenges one of the knights to a beheading game. Sir Gawain accepts the challenge and must seek out the Green Knight to receive his blow the following year. The document analyzes themes of courtesy, chivalry and keeping one's word through promises in the poem.

![5

17

Lines 37–84

• It is Christmas time (37); more specifically, New Year’s Day

(60). (Twelve days of Christmas = 25 December – 5 January.)

• The setting is Arthur’s court at Camelot. Everyone is taking part

in festive events, jousting, dancing, singing.

• Everyone is beautiful, youthful and happy:

All in that hall were beautiful, young and, of

their kind

The happiest under heaven, (54–56)

‘For al was this fayre folk in [their] first age’

• They exchange gifts (and kisses), then prepare for a feast, for

which Queen Guenevere has place of honour under a canopy of

expensive draperies.

18

Lines 85–129

• The king is restless, and refuses to sit down until everyone has

been served

He was in a merry mood, like a mischievous boy

His blood burned, his restless mind roused him (86, 89)

• He will also wait until either

Someone has told a story of adventure

or

Someone comes into the hall to challenge them to battle or

some other adventure

• Arthur wants something unusual to happen – either in a story,

or in real life.

• The feast continues; everything is of the best quality; everyone

is happy; everything is perfect …

• Or is it? Why does Arthur wait for something unusual? Is

something missing? Is peace not good enough?

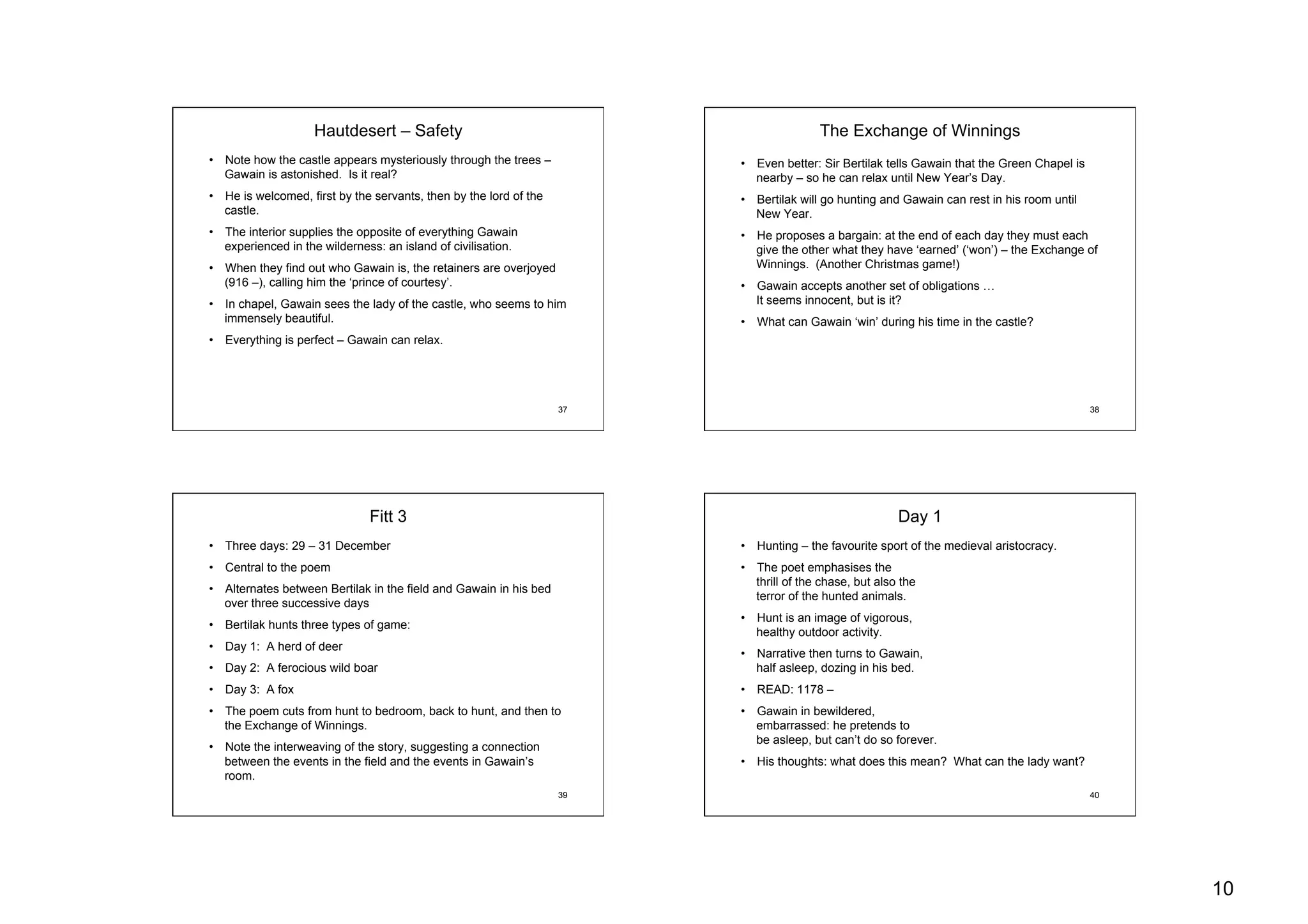

19

Poetic Technique

• Note how the poet lavishes attention on the smallest details …

• ‘Zooming’ technique

• But he also gives subtle hints that there are important issues

lying below the surface of what he is describing

• (1) Arthur’s court is youthful, joyful and energetic

• But this could also mean that it is inexperienced / untested /

maybe even impulsive / reckless

• Is Arthur being reckless in calling for a ‘marvel’?

• (2) The feast is magnificent, lacking in nothing …

• Is there an element of smugness / self-satisfaction here?

20

The arrival of the Green Knight

• The poet hints that everything is about to change because

‘another sound was stirring’ (132): something is approaching …

• Just as people were turning their attention to their food …

• When there hove into the court a hideous figure

[‘aghlich mayster’]

Square-built and bulky, full-fleshed from neck to thigh. (136–37)

• It’s a huge figure of a man, who may even have been ‘half-giant’

[‘half-etayn’].

• NB The word ‘giant’ [‘etayn’] has associations with savagery,

monstrous wild creatures that eat men, women & children

• BUT this figure is also ‘the mightiest of men’ and ‘a handsome

knight’ with an elegantly shaped body (141–44).

• What is he? Giant or huge man? Hideous or handsome? The

poet indicates that he’s both, and Arthur’s court can’t decide.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gawainlecturenotes-130607080222-phpapp01/75/Gawain-5-2048.jpg)

![6

21

‘Giant’ (‘etayn’)

– associations with

savagery, monstrous wild

creatures that eat men,

women & children

22

• The poet draws the reader into the sense of astonishment and

uncertainty experienced by Arthur’s court.

• They don’t know what they are looking at.

• The newcomer is a huge, well-dressed man – but everything

about him is green:

Not only was this creature

Colossal, he was bright green —

• The poet’s gaze takes in the knight’s magnificent clothes and

jewels

• These indicate that he’s someone from a very wealthy,

cultivated background;

• We begin to think that it’s only his clothes and decorations that

are green.

• But slowly we become aware that the whole man is green, and

so is his horse.

• WHAT IS HE? Is he giant or man? Human or supernatural?

• We share the uncertainty of Arthur’s court as they stare at the

Green Knight (GK).

23

Lines 179–249

• The knight’s appearance is also extraordinary in the way his hair

and his beard reach down to his elbows

• His horse’s mane is also elaborately decorated

• Is he a threat? The poet emphasises that he wears no

protective armour, but he carries:

• (1) A branch of green holly

(a sign of peace); and

(2) An enormous axe,

richly decorated

• A new ambiguity: does he stand for peace (holly), or for war

(the axe)? 24

Lines 179–249

• The knight’s appearance is ambiguous and confusing, but his

behaviour is downright rude:

‘Where is’, he said, ‘The leader of this lot?’

[‘Wher is’, he sayd, ‘The governour of this gyng?’]

• It should be obvious who is the king, but the GK pretends that

it’s not. (An obvious insult.)

• The court is stunned by the sight of the GK (Arthur wanted a

marvel!), but the poet emphasises that no one spoke for another

reason:

• They are waiting for Arthur to reply. Courtesy demands that he

identify himself (247).

• Courtesy is being identified as an important value.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gawainlecturenotes-130607080222-phpapp01/75/Gawain-6-2048.jpg)

![7

25

Lines 250–365

• Arthur courteously invites the GK to join them

• But he refuses: he’s there because of the high reputation of

Arthur’s knights for valour and courtesy.

• The GK says he wants no battle – then insults the knights as

‘beardless boys’

• What he wants is an exchange of blows – with his huge axe

• The court goes silent with astonishment, prompting the GK to

laugh at them all

• Arthur is furious, takes the axe and starts practising with it

• Then Gawain intervenes …

• With elaborate courtesy he asks Arthur to allow him to take up

the challenge (340–361)

26

Courtesy and Chivalry

• Courtesy – politeness, good manners, being respectful or

considerate, gentle, doing something out of generosity rather

than because you have to

• Courteous – ‘having manners fit for a royal court’;

knowing how to behave; cultivated, refined, polished, civilized

• The opposite of being brutal, ferocious, harsh – everything that

was expected of a fighter in a military society.

27

Courtesy and Chivalry

• Chivalry / Chivalrous: being polite, behaving well

• Chivalry – The qualities of an ideal knight: courage, honour,

courtesy, justice, readiness to help the weak

• Developed into a religious, social and moral code governing

behaviour ON and OFF the battlefield

• Courtesy and Chivalry express

the essential social and ethical

principles of medieval knighthood.

• Arthur’s court is famous for its

courtesy and chivlary

• The Green Knight challenges the

court to live up to its reputation

• The poet is questioning his society’s

ability to live up to its own values

28

The ‘Beheading Game’

• Arthur wanted a marvel – he seems to have got more than he

bargained for!

• The GK makes Gawain identify himself, and repeat the terms of

the ‘game’.

• He also makes Gawain swear by his troth [‘trawthe’] that he will

honour his side of the bargain.

• They make an agreement, a pact – a form of contract; a verbal

undertaking; a covenant (393).

• What does that mean? What should it mean?

• Should all promises be kept? – even if circumstances change?

• Note how the poet focuses again on the smallest details of the

beheading and what follows …](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gawainlecturenotes-130607080222-phpapp01/75/Gawain-7-2048.jpg)