Fractal Narrative About The Relationship Between Geometries And Technology And Its Impact On Narrative Spaces 1 Aufl German A Duarte

Fractal Narrative About The Relationship Between Geometries And Technology And Its Impact On Narrative Spaces 1 Aufl German A Duarte

Fractal Narrative About The Relationship Between Geometries And Technology And Its Impact On Narrative Spaces 1 Aufl German A Duarte

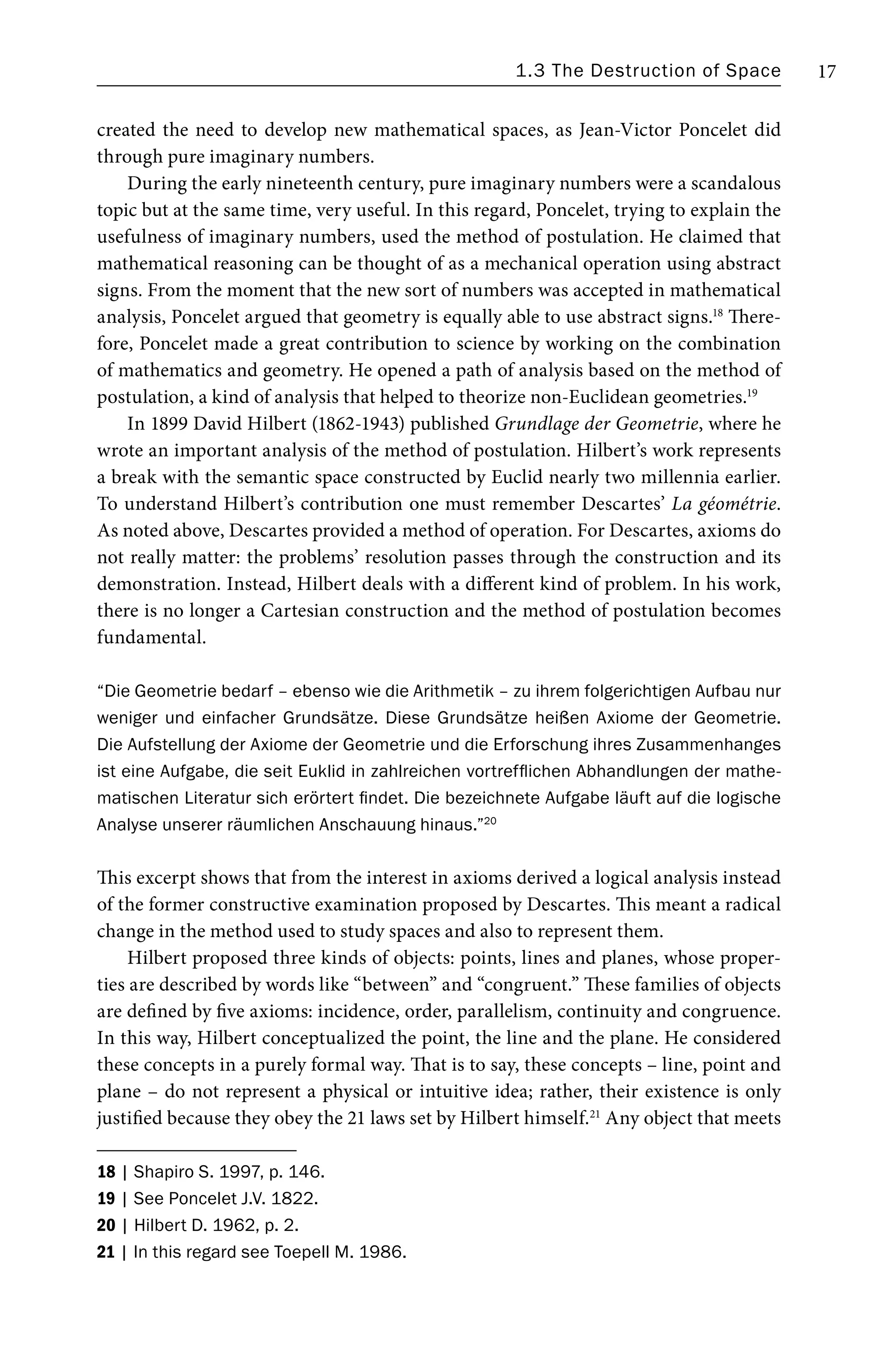

![1.4 Toward Fractality 25

“Il faut qu’on arrive à le construire [l’Analysis Situs] complètement dans des espaces

supérieurs ; on aura alors un instrument qui permettra réellement de voir dans l’hype-

respace et de suppléer à nos sens.”22

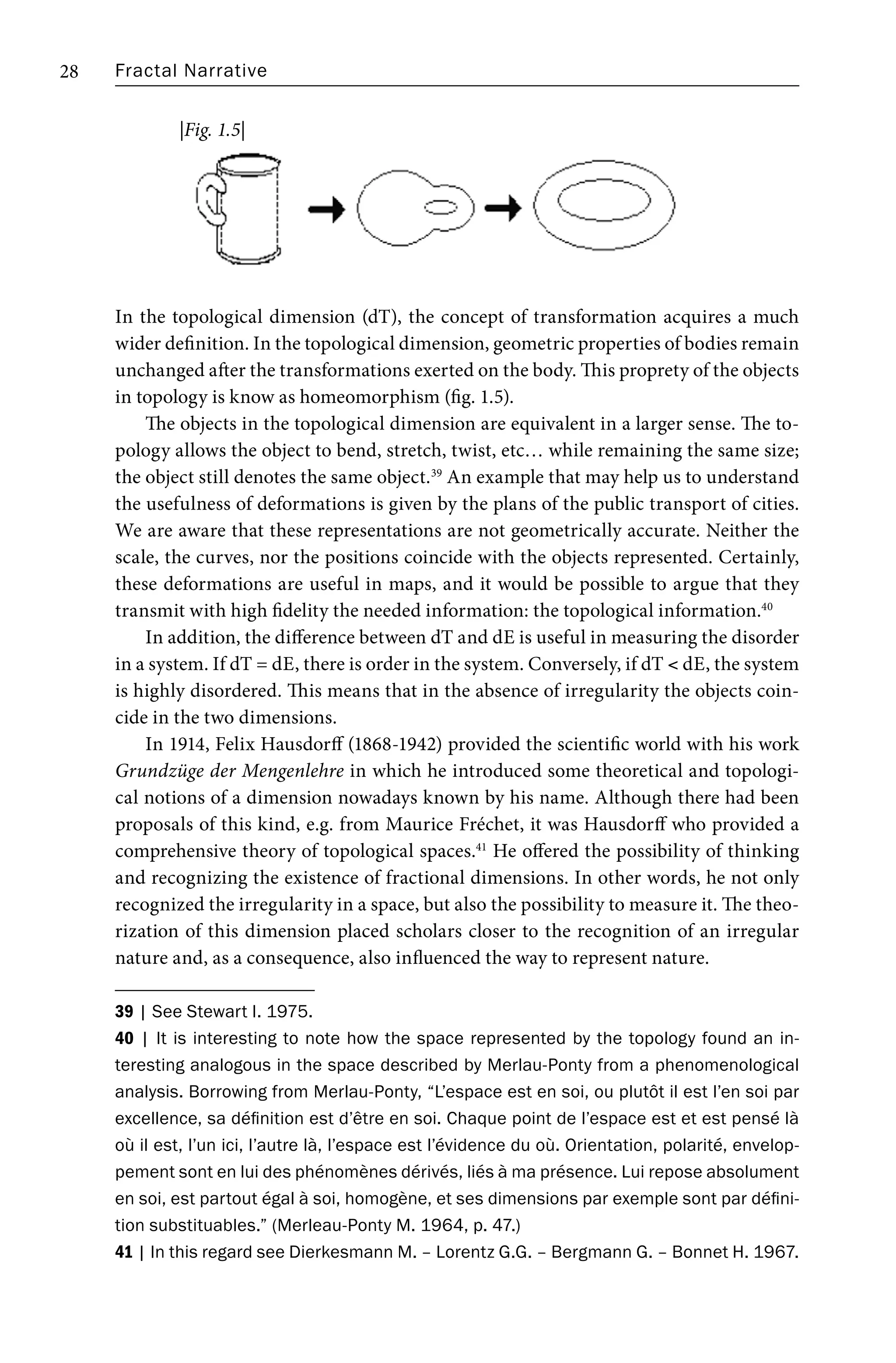

Topology represents a violent departure from the space built by the Greeks:

“La topologie impose l’oubli de la tradition et le souvenir d’une constitution spatiale

recouverte par l’équivoque du miracle grec, suspend le langage traditionnel comme am-

bigu et pratique la dissociation liminaire de la pureté non métrique et de la mesure.”23

But how does one imagine this space?

A factor that helped in designing the topological dimension was the relativity of

space theorized by Poincaré. He stated in the early twentieth century that space was

amorphous and that the objects placed into space gave it shape.24

In Günzel’s words:

“Für die topologische Raumbescreibung hilfreich sind dabei Relativierungen, welche von

Seiten der Mathematik und Physik nach Newton hinsichtlich der Raumauffassung vorge-

nommen wurden: Raum wird im Zuge dessen nicht mehr als eine dreifach dimensionier-

te Entität oder formale Einheit gefasst, sondern anhand von Elementen beschreiben, die

relational zueinander bestimmt werden. –Mit anderen Worten: An die Stelle des Ausdeh-

nungsaprioris tritt eine Strukturdarstellung von Raum.”25

|Prop. XI| This new character of the space, clearly influenced by Leibniz’s ideas, rep-

resents the peak of the revolutionary ideas of topology in the new way of conceiving

space.26

These shapes are placed into a space composed of a number of dimensions

that are assigned by our intellect.27

The space, at that point, could be understood as

a composition of dimensions necessary to respond to movements and forms derived

from a complex thought.28

Further, directly influenced by Leibniz’s theory of Analysis

22 | Poincaré H. 1908, p. 40.

23 | Serres M. 1993, p. 21.

24 | Poincaré H. 1908, p. 103.

25 | Günzel S. 2007, p. 17.

26 | See Günzel S. 2007.

27 | See Lefèbvre H. 20004

, especially Dessin de l’ouvrage.

28 | Note that thanks to Poincaré and Helmholtz the scientific world and the larger public

recognized that sense perceptions were relative. One can find, after Poincaré’s studies,

many articles and scientific researches focused on the relativity of the space theorized

by Poincaré, theories that imply a non-Euclidean geometry as well as the existence of

more than three dimensions in space. Examples include Sir William Crookes De la rela-

tivité des connaissances humaines, published in 1897 and Gaston Moch’s analysis of

it published in the Revue Scientifique the same year. Another interesting example is La

relativité de l’espace euclidien (1903) by Maurice Boucher.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/25900080-250514172217-8bf7a200/75/Fractal-Narrative-About-The-Relationship-Between-Geometries-And-Technology-And-Its-Impact-On-Narrative-Spaces-1-Aufl-German-A-Duarte-45-2048.jpg)

![1.4 Toward Fractality 27

notwithstanding, geometry, in turn, is also a means of analysis of spaces invented by

mankind and derived from abstractions of nature. In Poincaré’s words: “(…) Nous

avons créé l’espace qu’elle [geometry] étudie, mais en l’adaptant au monde où nous

vivons.”33

Thus, thanks to Poincaré, the notion of dimension started to be understood

as an instinctive concept built by our ancestors or somehow implanted in our child-

hood. In consequence, Poincaré could create a space that allowed him to question the

universal determinacy: the universe seen as a clock. By using geometric imagination,

Poincaré analyzed movement. Leibniz’s influence is clear. Leibniz’s Analysis Situs gen-

erates an interesting concept of movement. In fact, this geometric structure allows us

to determine movement by the relationships of spaces, by the relationship between

points, whose links determine movement.34

Thanks to this particular approach, Poin-

caré noted the chaotic character of nature, even though he did not define it clearly.35

Poincaré attempted to create a space able to accept some phenomena that could

not be accepted by the space governed by Euclidean geometry. One should remember

that in that period, geometry was neglected and considered obsolete, but Poincaré

created a new need for geometry and its language. Regarding geometry, he stated:

“Il nous permet donc encore de nous diriger dans cet espace qui est trop grand pour

nous et que nous ne pouvons voir, en nous rappelant sans cesse l’espace visible qui

n’en est qu’une image imparfaite sans doute, mais qui est encore une image. Ici encore,

comme dans tous les exemples précédents, c’est l’analogie avec ce qui est simple qui

nous permet de comprendre ce qui est complexe.”36

|Prop. XXII| Poincaré encouraged the use of geometry in order to create an alter-

native space useful for analyzing complex phenomena. As noted above, this space

emerged through the Analysis Situs, in which one finds the fundamental concepts of

topology:37

e.g. the principle of transformation, the disappearnce of the coordinates in

the space and the principle of invariableness.38

In Euclidean geometry, two objects are equivalent when it is possible to transform

one into the other by means of rotations or translations, that is to say transformations

that keep the angle, the size, the area and the volume.

33 | Poincaré H. 1908, p. 121

34 | See Heuser M.-L. 2007.

35 | See Ekeland I. 1995.

36 | Poincaré H. 1908, p. 39.

37 | Note that Poincaré’s work Analysis Situs derive from the study of the concepts of

Algebraic Topology. This research in multiple volumes, the first of which was edited in

1892 in Comptes-Rendus, was completed by a paper of 1895 entitled Analysis Situs.

Then, the notion of Analysis Situs was definitively completed in a series of papers edited

between 1899 and 1905, these entitled Compléments à l’Analysis Situs.

38 | See Dieudonné J. 1989, p. 18.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/25900080-250514172217-8bf7a200/75/Fractal-Narrative-About-The-Relationship-Between-Geometries-And-Technology-And-Its-Impact-On-Narrative-Spaces-1-Aufl-German-A-Duarte-47-2048.jpg)

![Fractal Narrative

34

quired an important utility in Mandelbrot’s research. They became the central thread

of all his work. The idea was that some aspects of the world have the same structure

at all scales, just the details change when one changes point of view. Thus, every little

piece of an object contains the ‘key’ of the entire construction, just like in a fractal

object.5

The fractal character of nature, according to Mandelbrot, is directly reflected

in the economy that nature applies in its structure. As Mandelbrot explains, nature

never uses different DNA codes, or different structures to create a branch of broccoli.

From the moment that a three-view system is created, nature generates branches pe-

riodically until it stops, as in the case of broccoli and the human lung. Ramification

of ramifications of ramifications, such as with broccoli in nature and the lung within

our body, the growth of a body is arranged with a simple code that can be defined as

the repetition of the smallest structure. The continuous, related repetition is the basis

of a fractal structure, simplicity within the complexity of nature.

This idea was first introduced to the scientific world by Poincaré in a work that

became vital for Mandelbrot’s research. In 1908, Poincaré highlighted this ‘simplicity’

of nature. He noted that thanks to this simplicity it is possible to conduct a study of

nature. According to Poncaré, the most interesting phenomena are those that can be

used multiple times because they can be renewed and applied to other circumstances.

The simplicity of nature, a simplicity of absolute complexity because of its infinite pos-

sibilities of combination, is what allows the existence of science. He used as example

the chemical elements. Assuming that the number of chemical elements was 60 bil-

lion, Poincaré states that science, in that case, would be almost useless because of the

inability to gain experience. It would be impossible to compare the elements because

each case would be almost unique:

“il y aurait une grande probabilité pour qu’il soit formé [un caillou] de quelque substance

inconnue ; tout ce que nous saurions des autres cailloux ne vaudrait rien pour lui ; de-

vant chaque objet nouveau nous serions comme l’enfant qui vient de naître ; comme lui

nous ne pourrions qu’obéir à nos caprices ou à nos besoins ; dans un pareil monde, il n’y

aurait pas de science ; peut-être la pensée et même la vie y seraient-elles impossibles,

puisque l’évolution n’aurait pu y développer les instincts conservateurs.”6

Poincaré was interested in the study of facts that can be repeated, namely simple facts

that can create complex structures, even infinite structures. He noted that in a com-

plex fact there are thousands of circumstances that meet by chance. As such, it was

necessary to develop a method to analyze and understand complex facts. As in the

case of a biologist who studies with more interest the single cell than the entire ani-

mal – because of the similarities that they have to the entire organism – the scientific

world started to develop the concept of symmetry between scales. Symmetry was un-

derstood as the beauty of nature, as the universal harmony in chaos.

5 | Mandelbrot B. 1997, p. 36.

6 | Poincaré H. 1908, p. 10.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/25900080-250514172217-8bf7a200/75/Fractal-Narrative-About-The-Relationship-Between-Geometries-And-Technology-And-Its-Impact-On-Narrative-Spaces-1-Aufl-German-A-Duarte-54-2048.jpg)