This document provides an overview of fractal geometry. It begins with an abstract that outlines how fractal patterns found in nature will be used to introduce the concept of fractals. It then provides a brief history of fractals, covering mathematicians like Georg Cantor and Benoit Mandelbrot who contributed to the discovery and study of fractals. The document goes on to examine key properties of fractals in depth, including recursion, self-similarity, iteration, and fractal dimension. It also provides examples of well-known fractals like the Sierpinski triangle and Mandelbrot set to illustrate these properties.

![AN EXPLORATION OF FRACTAL GEOMETRY 11

also have a dimension between 2 and 3 or between 0 and 1 (McGuire, p. 14). For example, if a

fractal surface has a dimension of 2.3 it would mean that it acts like a two-dimensional object

(such as a circle) but it is defined in a three-dimensional space. Consequently, fractal dimensions

such as these “are important because they can be defined in connection with real-world data, and

they can be measured approximately by means of experiments” (Barnsley, 1988, p. 172). What

are some factors than can alter or affect the fractal dimension? When using Mandelbrot’s ruler

method, something that will ultimately affect the dimensional result is the starting point which

one begins to measure the boundary (Landini, 2010, p. 6-7).

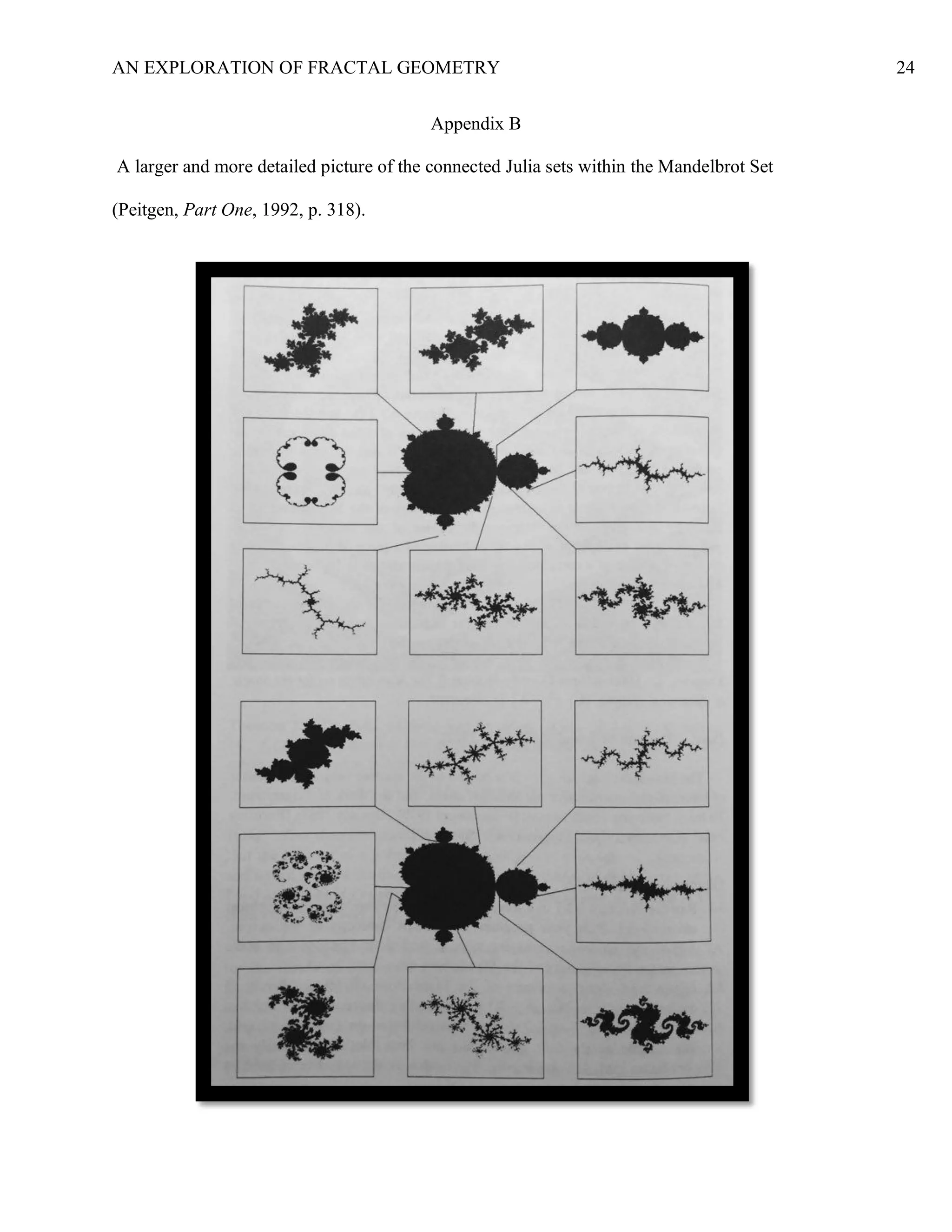

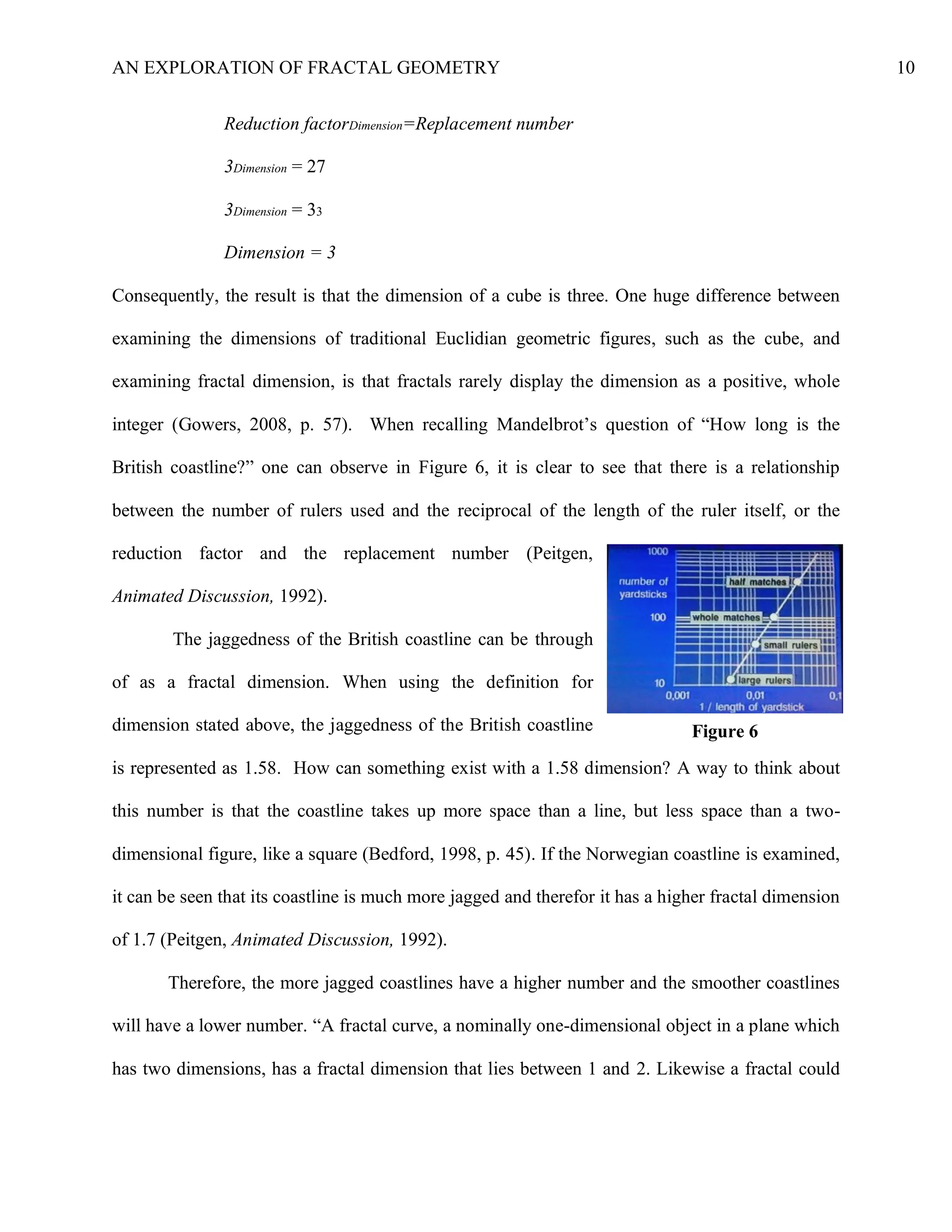

The Cantor Set

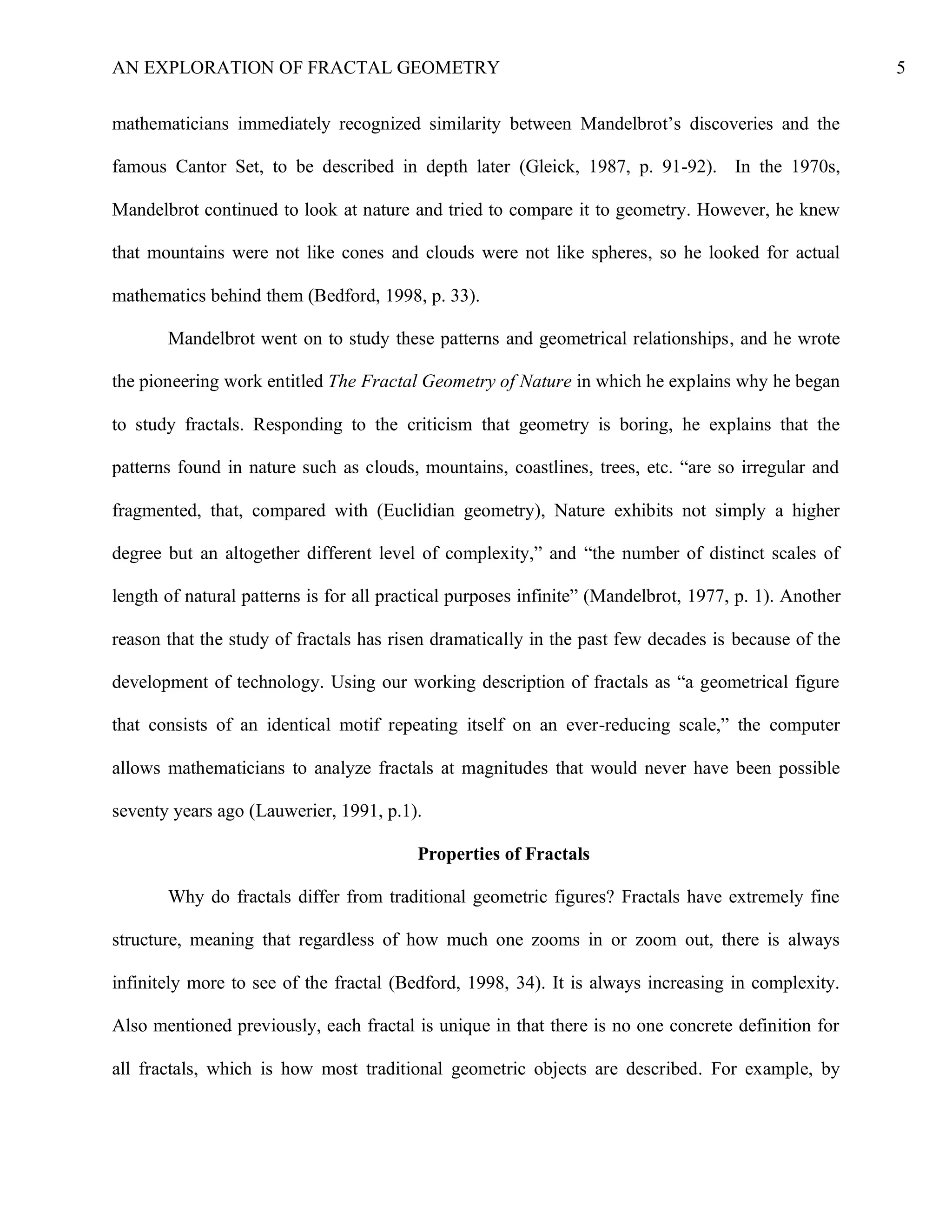

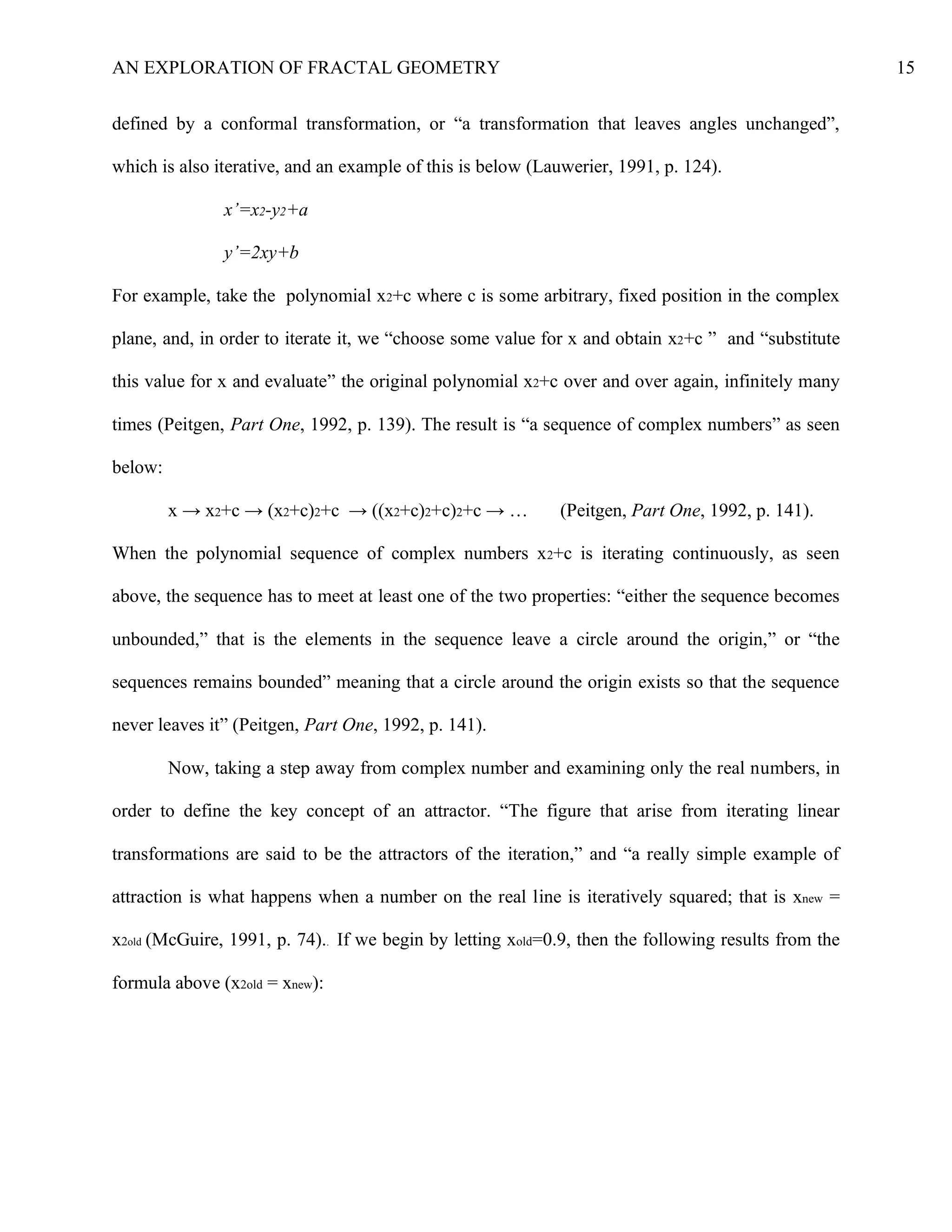

Now that the concepts of iteration, recursion, self-similarity, and fractal dimension have been

examined in depth, they will be examined against three famous fractals: the Cantor Set, the Koch

Curve, and the Julia Set. Firstly, the Cantor Set as seen in Figure 7 will be analyzed (Bedford,

1998, p. 47). The German mathematician Georg Cantor (1845-1918) contributed to mathematics

proving that irrational numbers are useful and have a

“logical place” in mathematics, and he is also one of the

main contributors of set theory (Lauwerier, 1991, p. 15).

As seen in Figure 7, the Cantor sets initial stage begins

with a line segment with a length of one, or representing

the interval [0, 1]. In Stage 1, one must “remove the middle third from [0, 1], but not the

numbers 1/3 and 2/3,” so what remains in Stage 1 are “two intervals [0, 1/3] and [2/3, 1] of

length 1/3 each” (Peitgen, Part One, 1992, p. 80). If you do this same process again, you are left

with the union of “four intervals: [0, 1/9] U [2/9, 1/3] U [2/3, 7/9] U [8/9, 1]” as seen in Stage 2

of Figure 7 (Bedford, 1998, p. 46). As you can see from Figure 7, after each iteration the

Figure 7: The Cantor Set](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexplorationoffractalgeometry-200429210906/75/An-Exploration-of-Fractal-Geometry-11-2048.jpg)

![AN EXPLORATION OF FRACTAL GEOMETRY 21

References

Barnsley, M. (1988). Fractals Everywhere. United States of America: Academic Press, Inc.

Bedford, C.W. (1998). Introduction to Fractals and Chaos: Mathematics and Meaning.

Andover, MA: Venture Publishing.

(n.d.) Untitled (British Coastline Image). [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://upload.

wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/Britain-fractal-coastline-combined.jpg.

Gleick, James. (1987). Chaos: Making a New Science. Harrisonburg, VA: R.R. Donnelley &

Sons Co.

Gowers, T. (Ed.) Barrow-Green, J. & Leader, I. (Assoc. eds.). (2008). The Princeton Companion

to Mathematics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Landini, G. (2010). Fractals in microscopy. Journal of Microscopy, 241(1), 1-8.

doi: 10.111/j.1365-2818.2010.03454.x

Lauwerier, H. A. (1991). Fractals: Endlessly Repeated Geometrical Figures. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Mandelbrot, Benoit B. (1977). The Fractal Geometry of Nature. New York: W.H. Freeman and

Company.

McGuire, Michael. (1991). An Eye For Fractals. United States of America: Addison-Wesley

Publishing Co., Inc.

Morphology [Def. 1]. (n.d.). Merriam-Webster Online. In Merriam-Webster. Retrieved

December 13, 2015, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/morphology

Parasher, R. (2008). Fractal Dimension: Measuring Infinite Complexity. Pi in The Sky, (12), 3-5.

Peitgen, H.O., Jurgens, H., Saupe, D., Maletsky, E., Perciante, T., & Yunker, L. (1992). Fractals

for the Classroom: Part One Introduction to Fractals and Chaos. Rensselaer, NY:

Springer-Verlag New York, Inc.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexplorationoffractalgeometry-200429210906/75/An-Exploration-of-Fractal-Geometry-21-2048.jpg)

![AN EXPLORATION OF FRACTAL GEOMETRY 22

Peitgen, H.O., Jurgens, H., Saupe, D., & Zahlten C. (Producers). (1990). Fractals: An Animated

Discussion [VHS]. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Strzyzewski, F. [Florian Strzyżewski]. (2008, May 3). More about Julia Set Fractal - part 1 of 3.

[Video File]. Retreived from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RAgR_KVWtcg&

index=2&list=PLymzxCT1I9d3cmOQgZWwjff6jd0uEW0kk.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexplorationoffractalgeometry-200429210906/75/An-Exploration-of-Fractal-Geometry-22-2048.jpg)