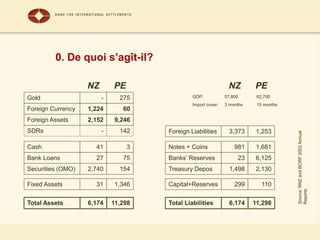

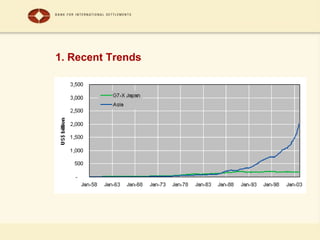

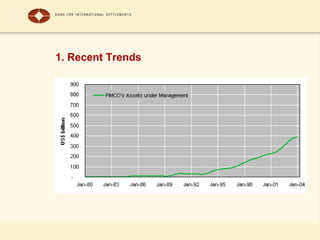

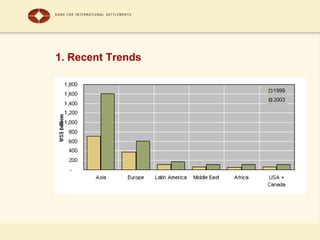

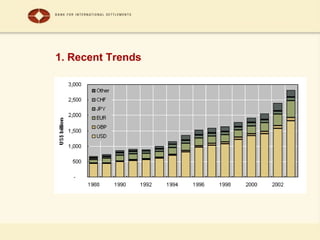

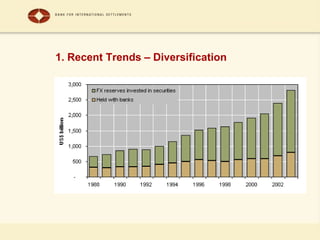

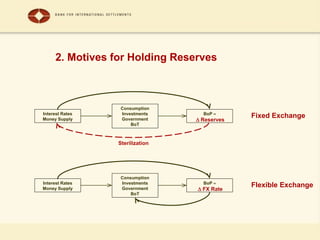

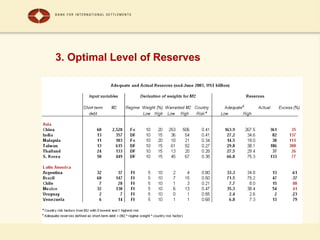

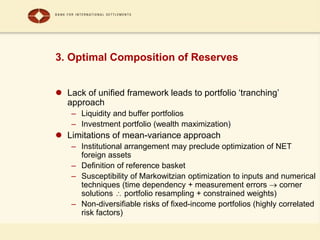

The document discusses foreign exchange reserves, including what they are, why countries hold them, who manages them, and debates around optimal levels. It addresses recent trends showing growing reserves held mostly as foreign currencies, with diminishing gold reserves. Motivations for holding reserves include transactions needs, intervention for stability, and diversification. There is no agreed framework for determining optimal levels, but factors like monetary policy, exchange rates, external exposure, and financial market development are relevant.

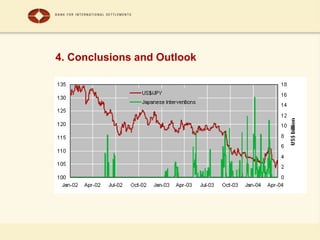

![4. Conclusions and Outlook

FX intervention back ‘en-vogue’ in low-inflation, low-interest

rate environment

Large scale intervention by Japanese MoF

– Cumulative amount US$ 375bn since mid-2002

– Approx. US$ 145bn during Q1 2004

RBNZ announces intervention as official policy tool for

“insurance purposes”

– “[…] an additional instrument to achieve Policy Target

Agreement obligations”

– “[…] restore order to dysfunction in the foreign exchange

market”

Anecdotal evidence of ECB and SNB intervention activity](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01reserveleveloptimisationbieri-160108042646/85/Foreign-Exchange-Reserve-Level-Optimisation-32-320.jpg)