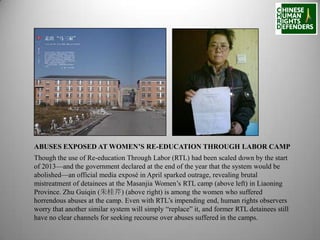

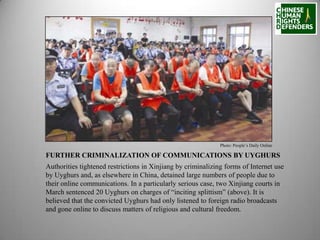

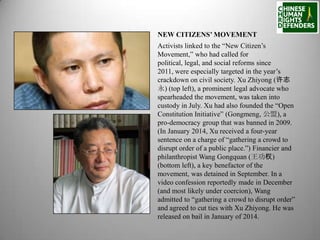

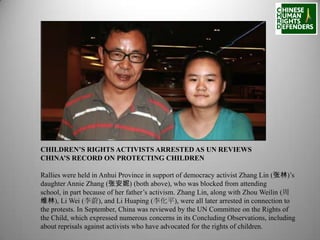

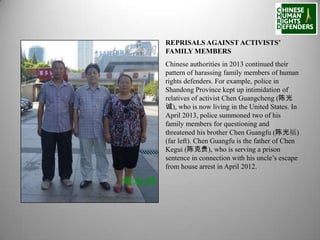

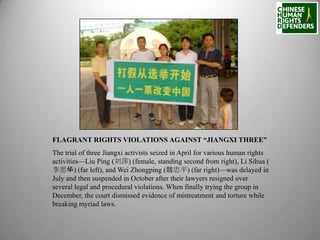

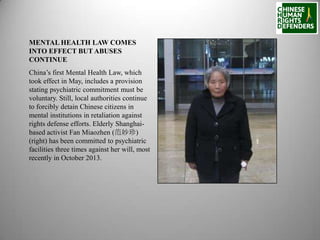

The document provides a year-in-review of human rights issues in China in 2013. It summarizes protests over press censorship, exposes abuses at women's labor camps, and crackdowns on activists advocating for transparency, free speech, and children's rights. Journalists, lawyers, petitioners, and ethnic minority groups faced increased harassment, detention, and prosecution for exercising basic freedoms or advocating for political reforms. Despite new laws, human rights conditions in China continued to deteriorate as authorities suppressed dissent and tightened control over civil society.