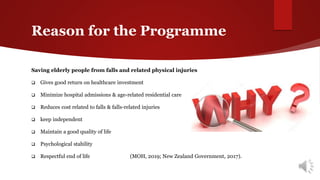

This document describes a proposed Motivational Adaptive Physical Activity Programme (MAPAP) for fall prevention among elderly people in New Zealand. The programme would be community-based and use behavioral change models to motivate elderly individuals to participate in physical activities to improve strength, balance, and flexibility through group sessions. A three-stage intervention approach is outlined involving pre-assessment, adaptive physical activity sessions, and post-evaluation. The goal is to reduce falls and fall-related injuries among the elderly population to improve quality of life and reduce healthcare costs.

![ Elderly people are adults over the age of 65 years.

Globally it is predicted that by 2050, the elderly population to reach 2 billion

from 900 million in 2015.

Currently, 125 million people are 80-year-old or over.

(World Health Organization [WHO], 2018).

In New Zealand (NZ) the rate of elderly population is growing swiftly

This extended life span is seen as a victory of medical advances

However, it has increased the load on healthcare services due to health issues

associated with old age. (Ministry of Health (MOH), 2019; WHO, 2018).

15

22

6

12

2 4

0

5

10

15

20

25

2015/16 2035/36

Growing

rate

in

percentage

Elderly population growing rate in NZ

(MOH, 2018)

65 years 75 years 85 years](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mapap-210127014203/85/fall-prevention-Motivational-physical-activity-program-MPAP-for-fall-prevention-2020-2-320.jpg)