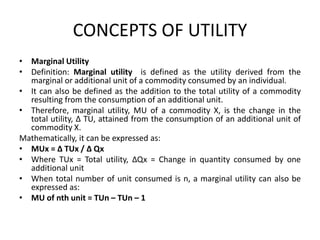

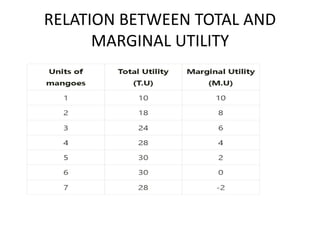

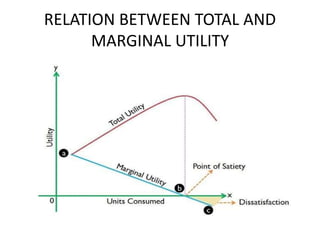

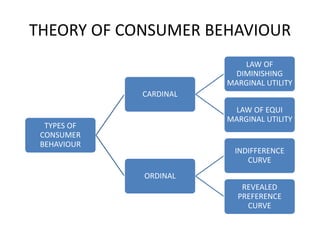

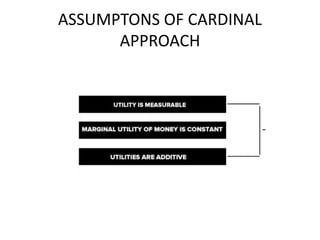

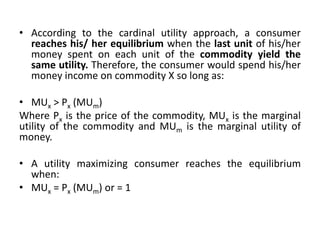

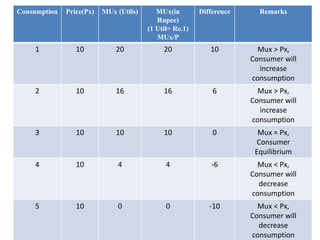

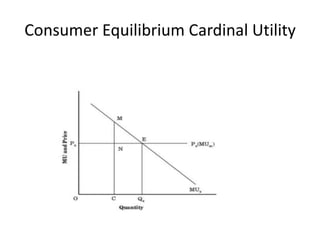

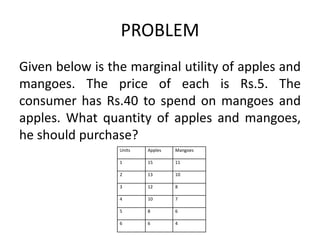

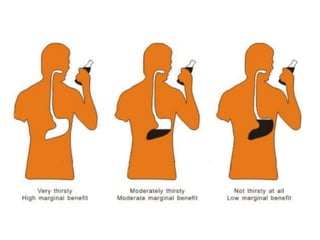

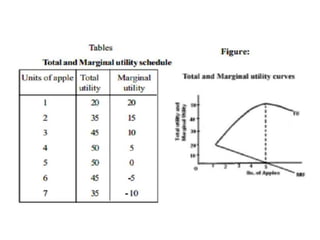

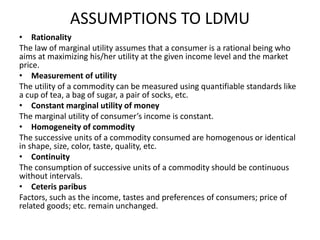

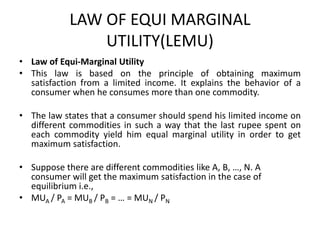

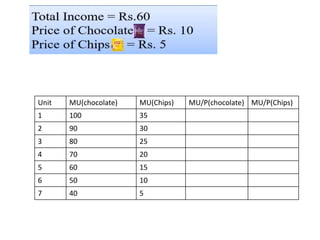

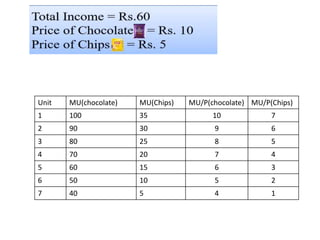

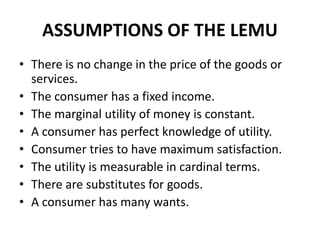

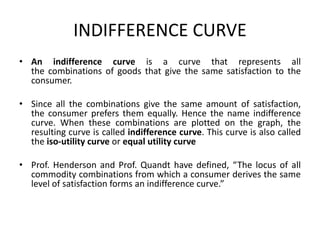

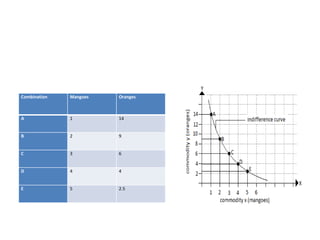

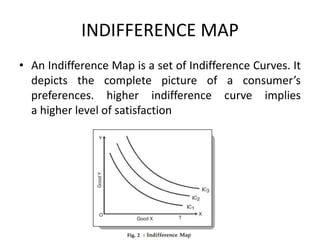

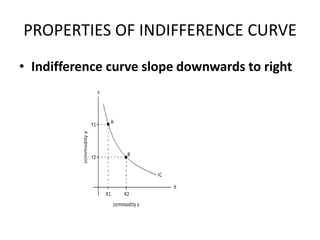

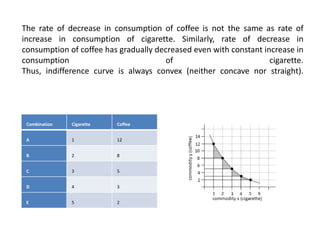

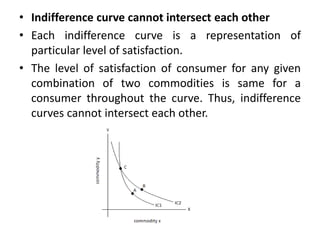

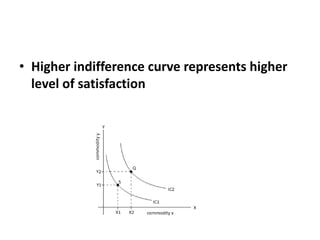

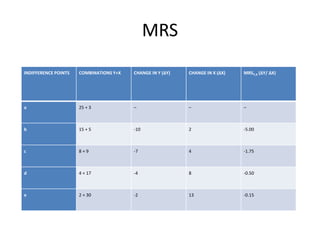

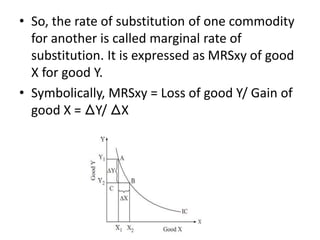

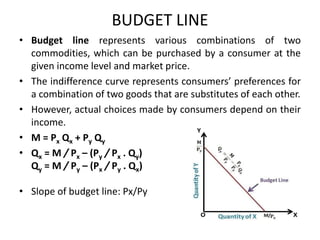

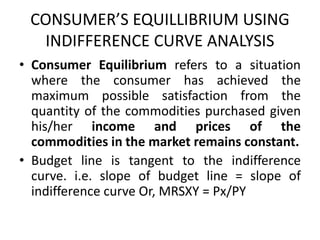

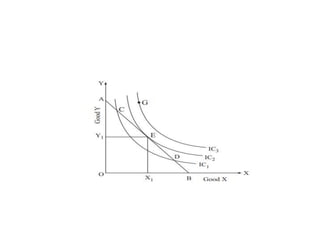

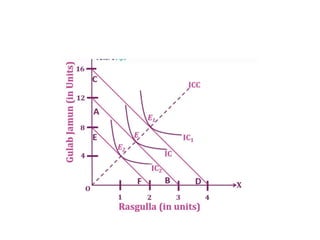

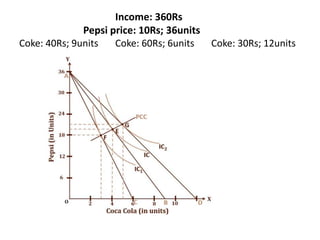

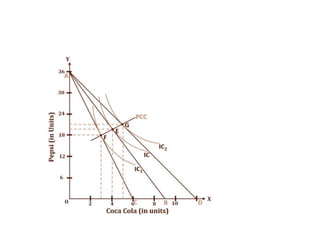

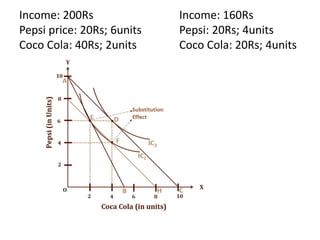

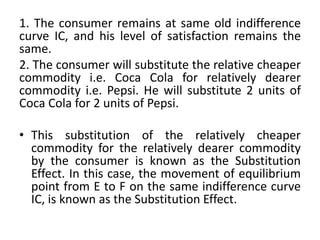

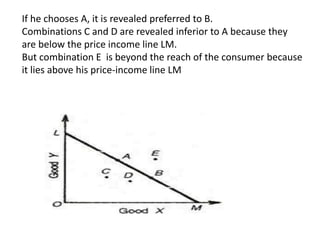

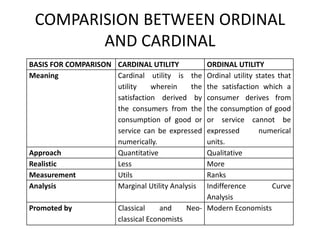

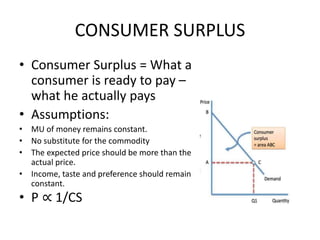

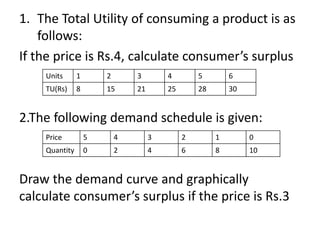

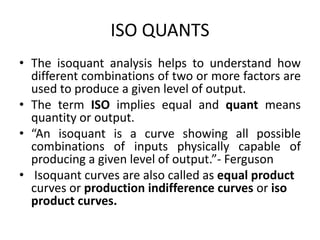

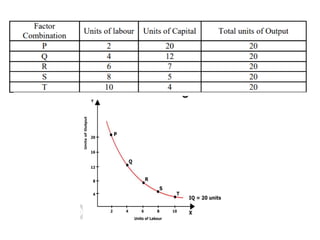

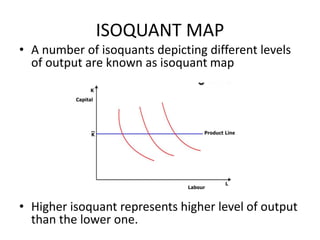

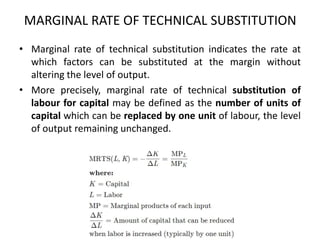

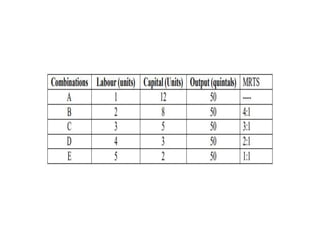

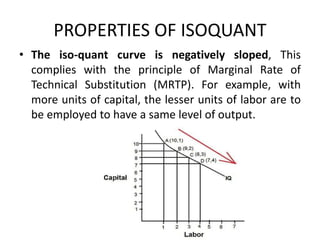

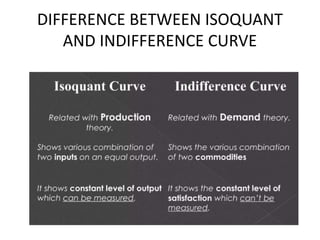

The document discusses consumer behavior, focusing on the study of individuals' purchasing patterns and the concept of utility, which measures consumer satisfaction derived from goods or services. It outlines key concepts such as total and marginal utility, the law of diminishing marginal utility, and various approaches to understanding consumer behavior, including cardinal and ordinal utility theories. Additionally, it introduces the concepts of indifference curves, budget lines, and the effects of income and price changes on consumer equilibrium.