This document is Darin Chester Hitchings' PhD dissertation submitted to Boston University. It develops new algorithms for controlling teams of robots performing information-seeking missions in unknown environments with limited sensing budgets. The dissertation first considers scenarios with finite action and measurement spaces and develops algorithms using Lagrangian relaxation and receding horizon control. It then extends these methods to problems with moving objects, continuous action/measurement spaces, and considers how human operators can work with robotic teams. The goal is to maximize information gained about objects while efficiently using limited sensing resources.

![3.4 Bounds for the simulations results in Table 3.3. When the horizon is short,

the 3 MPC algorithms execute more observations per object than were used

to compute the “bound”, and therefore, in this case, the bounds do not match

the simulations; otherwise, the bounds are good. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

3.5 Comparison of lower bounds for 2 homogeneous, bi-modal sensors (left 3 columns)

versus 2 heterogeneous sensors in which S1 has only ‘mode1’ available but S2

supports both ‘mode1’ and ‘mode2’ (right 3 columns). There is 1 visibility-

group with πi(0) = [0.7 0.2 0.1]T

∀ i ∈ [0..99]. For many of the cases studied

there is a performance hit of 10–20%. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

3.6 Comparison of sensor overlap bounds with 2 homogeneous, bi-modal, sensors

and 3 visibility-groups. Both configurations use the prior πi(0) = [0.7 0.2 0.1]T

.

Compare and contrast with the left half of Table 3.5, most of the time the two

sensors have enough objects in view to be able to efficiently use their resources

for both the 60% and 20% overlap configurations; only the bold numbers are

different. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

3.7 Simulation results for 3 homogeneous sensors without using detection but with

partial overlap as shown in Fig. 3·5. See Fig. 3·6 - Fig. 3·8 for the graphical

version. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

3.8 Bounds for the simulations results in Table 3.7. When the horizon is short,

the 3 MPC algorithms execute more observations per object than were used to

compute the bound, and therefore, in this case, the bounds do not match the

simulations; otherwise, the bounds are good. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

5.1 Performance comparison averaged over 100 Monte Carlo simulations. Re-

laxation is the algorithm proposed in this chapter, while Exact is the

algorithm of [Bashan et al., 2008] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

xii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-14-320.jpg)

![2·6 Illustration of “tracing” or “walking” a decision-tree for a POMDP sub-

problem to calculate expected measurement and classification costs (the

individual costs from the total). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

2·7 Strategy 1 (mixture weight=0.726). πi(0) = [0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1]’ ∀ i ∈ [0, . . . , 9],

πi(0) = [0.80 0.12 0.06 0.02]T

∀ i ∈ [10, . . . , 99]. The first 10 objects start with

node 5, the remaining 90 start with node 43. The notation [i Ni0 Ni1 Ni2]

indicates the next node/action from node i as a function of observing the 0th,

1st or 2nd observations respectively. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

2·8 Strategy 2 (mixture weight=0.274) πi(0) = [0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1]’ ∀ i ∈ [0, . . . , 9],

πi(0) = [0.80 0.12 0.06 0.02]T

∀ i ∈ [10, . . . , 99]. The first 10 objects start with

node 6, the remaining 90 start with node 18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

2·9 The 3 pure strategies that correspond to columns 2, 5 and 6 of Table 2.2. The

frequency of choosing each of these 3 strategies is controlled by the relative

proportion of the mixture weight qc ∈ (0..1) with c ∈ {2, 5, 6}. . . . . . . . . 36

3·1 Illustration of scenario with two partially-overlapping sensors. . . . . . . . . 44

3·2 This figure is the graphical version of Table 3.3 for horizon 3. Simulation results

for two sensors with full visibility and detection (X=’empty’, ’car’, ’truck’, ’mil-

itary’) using πi(0) = [0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1]T

∀ i ∈ [0..9], πi(0) = [0.80 0.12 0.06 0.02]T

∀ i ∈ [10..99]. There is one bar in each sub-graph for each of the three simula-

tion modes studied in this chapter. The theoretical lower bound can be seen

in the upper-right corner of each bar-chart. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

3·3 This figure is the graphical version of Table 3.3 for horizon 4. . . . . . . . . 47

3·4 This figure is the graphical version of Table 3.3 for horizon 6. . . . . . . . . 48

3·5 The 7 visibility groups for the 3 sensor experiment indicating the number of

locations in each group. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

xiv](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-16-320.jpg)

![3·6 This figure is the graphical version of Table 3.7 for horizon 3. Situation with

no detection but limited visibility (X=’car’, ’truck’, ’military’) using πi(0) =

[0.70 0.20 0.10]T

∀ i ∈ [0..99]. There were 7 visibility-groups: 20x001, 20x010,

20x100, 12x011, 12x101, 12x110, 4x111. The 3 bars in each sub-graph are for

‘str1’, ‘str2’, ‘str3’ respectively. The theoretical lower bound can be seen in the

upper-right corner of each bar-chart. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

3·7 This figure is the graphical version of Table 3.7 for horizon 4. . . . . . . . . 52

3·8 This figure is the graphical version of Table 3.7 for horizon 6. . . . . . . . . 53

4·1 An example HMM that can be used for each of the N locations. pa is an

arrival probability and pd is a departure probability for the Markov chain. 57

5·1 Depiction of measurement likelihoods for empty and non-empty cells as a func-

tion of xk0.

√

xk0 gives the mean of the density p(Yk0|Ik = 1). If the cell is

empty the observation is always mean 0 (black curve). . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

5·2 Waterfall plot of joint probability p(Yk0|Ik; xk0) for πk0 = 0.50 for xk0 ∈

[0 . . . 20]. This figure shows the increased discrimination ability that results

from using higher-energy measurements (separation of the peaks). . . . . . . 75

5·3 Graphic showing the posterior probability πk1 as a function of the initial ac-

tion xk0 and the initial measurement value Yk0. This surface plot is for λ = 0.01

and πk0 = 0.20. (The boundary between the high (red) and low (blue) portions

of this surface is not straight but curves towards -y with +x.) . . . . . . . . 76

5·4 Cost function boundary (see Eq. 5.14) with λ = 0.011 and πk0 = 0.18. In the

lighter region two measurements are made, in the darker region just one. (Note

positive y is downwards.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

xv](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-17-320.jpg)

![5·5 The optimal boundary for taking one action or two as a function of (xk0, Yk0)

(for the [Bashan et al., 2008] cost function) for λ = 0.01 and πk0 = 0.20. The

curves in Fig. 5·6 represent cross-sections through this surface for the 3 x-values

referred to in that figure. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

5·6 This figure gives another depiction of the optimal boundary between taking

one measurement action or two for the [Bashan et al., 2008] cost function. For

all Y (xk0, λ) ≥ 0 two measurements are made (and the highest curve is for the

smallest xk0, see Fig. 5·5 for the 3D surface from which these cross-sections

were taken). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

5·7 Two-factor exploration to determine how the optimal boundary between taking

one measurement or two measurements varies for a cell with the parameters

(p, λ) where p = πk0 (for the [Bashan et al., 2008] problem cost function). Two

measurements are taken in the darker region, one measurement for the lighter

region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

5·8 Plot of cost function samples associated with false alarms, missed detections

and the optimal choice between false alarms and missed detections (for the

Bayes’ cost function). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

5·9 This figure shows cost-to-go function samples as a function of the second

sensing-action xk1 and the second measurement Yk1 for the Bayes’ cost func-

tion. These plots use 1000 samples for Yk1 and 100 for xk1. . . . . . . . . . . 87

5·10 Threshold function for declaring a cell empty (risk of MD) or occupied (risk of

FA). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

5·11 The 0th stage resource allocation as a function of prior probability. The stria-

tions are an artifact of the discretization of resources when looking for optimal

xk0. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

xvi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-18-320.jpg)

![5·12 Total resource allocation to a cell as a function of prior probability. The point-

wise sums of the 0th stage and 1st stage resource expenditures are displayed

here. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

5·13 Cost associated with a cell as a function of prior probability. For the optimal

resource allocations, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the cost of

a cell and the resource utilized to sense a cell. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

5·14 Cost-to-go from πk1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

5·15 Optimal stage 1 energy allocations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

5·16 Stage 0 energy allocation versus prior probability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

6·1 Graphical User Interface (GUI) concept for semi-autonomous search and

exploitation strategy game. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

A·1 Hyperplanes representing the optimal Value Function (cost framework)

for the canonical Wald Problem [Wald, 1945] with horizon 3 (2 sensing

opportunities and a declaration) for the equal missed detection and false

alarm cost case: FA=MD. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119

A·2 Decision-tree for the Wald Problem. This figure goes with Fig. A·1. . . . 119

A·3 Example of 3D hyperplanes for a value function (using a reward formu-

lation for visual clarity) for X = {‘military’,‘truck’,‘car’,‘empty’}, S = 1,

M = 3 for a horizon 3 problem. The cost coefficients for the non-military

vehicles were added together to create the 3D plot. This figure and

Fig. A·4 are a mixed-strategy pair. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

A·4 Example of 3D hyperplanes representing the optimal value function re-

turned by Value Iteration. The optimal value is the convex hull of these

hyperplanes. This figure and Fig. A·3 are a mixed-strategy pair (see

Section 2.3). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

xvii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-19-320.jpg)

![5

multiple, multi-modal, resource-constrained sensors on autonomous vehicles by specify-

ing where and how they should be used to maximize one of several possible performance

metrics for the mission. The goals of the mission are application-dependent, but at the

very least they will include accurately locating, observing and classifying objects in the

mission space.

The SM control problem can be formulated as a Partially Observed Markov Decision

Problem (POMDP), but its exact solution requires excessive computation. Instead, we

use Lagrangian Relaxation techniques to decompose the original SM problem hierarchi-

cally into POMDP subproblems with coupling constraints and a master problem that

coordinates the prices of resources. To this end, this dissertation makes the following

contributions:

• Develops a Column Generation algorithm that creates mixed strategies for SM and

implements this algorithm in fast, C language code. This algorithm creates sensor plans

that near-optimally solve an approximation of the original SM problem, but generates

mixed strategies that may not be feasible. The output strategies are programmatically

visualized in MATLAB.

• Develops alternatives for receding horizon control using these approximate, mixed strate-

gies output from the Column Generation routine, and evaluates their performance using

a fractional factorial design of experiments based on the above software.

• Extends previous results in SM for classification of stationary objects to allow Markov

dynamics and time varying visibility, obtaining new lower bounds characterizing achiev-

able performance for these problems. These lower bounds can be used to develop receding

horizon control strategies.

• Develops new approaches for solution of dynamic search problems with continuous ac-

tion and observation spaces that are much faster than previous optimal results, with

near-optimal performance. We perform simulations of our algorithms in MATLAB and

compare our results with those of the optimal algorithm from [Bashan et al., 2007,Bashan

et al., 2008]. Our algorithm performs similarly to theirs but can be used for problems

with non-uniform priors.

• Designs a game to explore human supervisory control of automata controlled by our](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-27-320.jpg)

![6

algorithms, in order to explore the effects of different levels of information support on

the quality of supervisory control.

1.3 Dissertation Organization

The structure of the remainder of this dissertation is as follows: Chapter 2 is devoted

to presenting a literature survey and background material that is pertinent to the SM

problem. Chapter 2 also reviews theory from [Casta˜n´on, 2005b] that underlies the

theoretical foundations of this dissertation’s results. Chapter 3 builds upon the results

of Chapter 2 and discusses a RH algorithm for near-optimal SM in a scenario where

objects have static state and sensor platforms are unconstrained in terms of where they

look and when (no motion constraints). Chapter 4 discusses new algorithms for two

extensions to the problem formulation of Chapter 3: 1) objects that can arrive and

depart with a Markov birth-death process or 2) object visibility that is known but time-

varying. Chapter 5 considers an adaptive search problem for sensors with continuous

action and observation spaces and presents fast, near-optimal algorithms for the solution

of these problems. Chapter 6 discusses some candidate strategies for mixed human/non-

human, semi-autonomous robotic search and exploit teams and develops a game that can

be used to explore human supervisory control of robotic teams. Chapter 7 summarizes

this dissertation. Last of all, two appendices are included that provide some additional

background theory and documentation for the simulator discussed in Chapter 3.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-28-320.jpg)

![7

Chapter 2

Background

This chapter provides both a literature survey and background material that will be

referred to in later chapters. First we review existing techniques from various fields

related to this dissertation. We describe why the algorithms presented in the litera-

ture fail to address the problem we envision to the extent that is required for a search

and exploitation system to be considered “semi-autonomous”, which we take to mean

an Autonomous Capability Level (ACL) of 6 or higher on the DoDs “UAV Roadmap

2009” [United States Department of Defense, 2009]. Section 2.2 discusses the develop-

ment of a lower bound for the achievable performance of a SM system from [Casta˜n´on,

2005b]. The last section in this chapter, Section 2.3, gives an example of our algo-

rithm for computing SM plans. The implementation of the algorithm from [Casta˜n´on,

2005b], as demonstrated by this example, is the first contribution of this dissertation.

For the interested reader, a brief review of theory pertaining to Partially Observable

Markov Decision Processes (POMDPs), the Witness Algorithm and Point-Based Value

Iteration (PBVI), Dantzig-Wolfe Decompositions and Column Generation is available

in Appendix A.

2.1 Literature Survey

Problems of search and exploitation have been considered in many fields such as Search

Theory, Information-Theory, Multi-armed Bandit Problems (MABPs), Stochastic Con-

trol, and Human-Robot Interactions. We will review relevant results in each of these](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-29-320.jpg)

![8

areas in the rest of this section.

2.1.1 Search Theory

One of the earliest examples of Sensor Management (SM) arose in the context of Search,

with application to anti-submarine warfare in the 1940’s [Koopman, 1946, Koopman,

1980]. In this context, Search Theory was used to characterize the optimal allocation

of search effort to look for a single stationary object with a single imperfect sensor.

Sensors had the ability to move spatially and allocate their search effort over time and

space. In [Koopman, 1946] a worst-case search-performance rule is derived yielding the

“Random Search Law” aka the “Exponential Detection Function” [Stone, 1977]. This

work is extended in [Stone, 1975] to handle the case of a single moving object. A survey

of the field of Search Theory is given by [Benkoski et al., 1991], which describes how

most work in this domain focuses on open-loop search plans rather than feedback control

of search trajectories.

The main problem with most Search Theory results is that the search strategies are

non-adaptive and the search ends after the object has been found. Extensions of Search

Theory to problems requiring adaptive feedback strategies have been developed in some

restricted contexts [Casta˜n´on, 1995] where a single sensor takes one action at a time.

Recent work on Search has focused on deterministic control of search vehicle tra-

jectories using different performance metrics. Baronov et al. [Baillieul and Baronov,

2010,Baronov and Baillieul, 2010] describe an information aquisition algorithm for the

autonomous exploration of random, continuous fields in the context of environmental

exploration, reconaissance and surveillance. Our focus in this thesis is on adaptive

sensor scheduling based on noisy observations, and not on control of sensor-platform

trajectories.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-30-320.jpg)

![9

2.1.2 Information Theory for Adaptive Sensor Management

Adaptive SM has its roots in the field of statistics, in which Bayesian experiment design

was used to configure subsequent experiments that were based on observed information.

Wald [Wald, 1943,Wald, 1945] considered sequential hypothesis testing with costly ob-

servations. Lindley [Lindley, 1956] and Kiefer [Kiefer, 1959] expanded the concepts

to include variations in potential measurements. Chernoff [Chernovv, 1972] and Fe-

dorov [Fedorov, 1972] used Cramer-Rao bounds for selecting sequences of measurements

for nonlinear regression problems. Most of the strategies proposed for Bayesian experi-

ment design involve single-step optimization criteria, resulting in “greedy” (or “myopic”)

strategies that optimize bounds on the expected performance after the next experiment.

Athans [Athans, 1972] considered a two-point boundary value approach to controlling

the error covariance in linear estimators by choosing the measurement matrices. Other

approaches to adaptive SM using single-stage optimization have been proposed with al-

ternative information theoretic measures [Schmaedeke, 1993,Schmaedeke and Kastella,

1994,Kastella, 1997,Kreucher et al., 2005].

Most of the work on information theory approaches for SM is focused on tracking

objects using linear or nonlinear estimation techniques [Kreucher et al., 2005,Wong et al.,

2005,Grocholsky, 2002,Grocholsky et al., 2003] and use myopic (single stage) policies.

Myopic policies generated by entropy-gain criteria perform well in certain scenarios,

but they have no guarantees for optimality in dynamic optimization problems. Along

these lines, the dissertation by Williams provides a set of performance bounds on greedy

algorithms as compared to optimal closed-loop policies in certain situations [Williams,

2007].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-31-320.jpg)

![10

2.1.3 Multi-armed Bandit Problems

In the 1970s [Gittins, 1979] developed an optimal indexing rule for “Multi-armed Bandit

Problems” (MABP) that is applicable to SM problems. In these approaches, different

objects are modeled as ”bandits” and assigning a sensor to look at an object is equivalent

to playing the ”bandit”, thereby changing the ”bandit’s” state. Krishnamurthy et al.

[Krishnamurthy and Evans, 2001a,Krishnamurthy and Evans, 2001b] and Washburn et

al. [Washburn et al., 2002] use MABP models to obtain SM policies for tracking moving

objects. The MABP model limits their work to policies that use a single sensor with a

single mode, so only one object can be observed at a time.

2.1.4 Stochastic Control

Stochastic control approaches to SM problems are often posed as Stochastic Control

Problems and solved using Dynamic Programming techniques [Bertsekas, 2007]. Evans

and Krishnamurthy [Krishnamurthy and Evans, 2001a] use a Hidden Markov Model

(HMM) to represent object dynamics while planning sensor schedules. Using a Stochas-

tic Dynamic Programming (SDP) approach, optimal policies are found for the cost

functions studied. While the proposed algorithm provides optimal sensor schedules for

multiple sensors, it only deals with one object.

Several authors have recently proposed approximate Stochastic Dynamic Program-

ming techniques for SM based on value function approximations or reinforcement learn-

ing [Wintenby and Krishnamurthy, 2006,Kreucher and Hero, 2006,Chong et al., 2008a,

Washburn et al., 2002,Schneider et al., 2004,Williams et al., 2005,Chong et al., 2008a,

Chong et al., 2008b]. The majority of these results are focused on the problem of track-

ing objects. Furthermore, the proposed approaches are focused on small numbers of

objects, and fail to address the range and scale of the problems of interest in this dis-

sertation. A good overview of approximate DP techniques is available in [Casta˜n´on and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-32-320.jpg)

![11

Carin, 2008].

Bashan, Reich and Hero [Bashan et al., 2007, Bashan et al., 2008] use DP to solve

a class of two-stage adaptive sensor allocation problems for search with large numbers

of possible cells. The complexity of their algorithm restricts its application to problem

classes where every cell has a uniform prior. Similar results were obtained for an imaging

problem in [Rangarajan et al., 2007]. In this thesis, we develop a different approach that

overcomes this limitation in Ch. 5.

In [Yost and Washburn, 2000], Yost describes a hierarchical algorithm for resource

allocation using a Linear Program (LP) at the top level (the “master problem”) to

coordinate a set of POMDP subproblems in a Battle Damage Assessment (BDA) setting.

This work is similar to the approach of this dissertation, except we are concerned with

more complicated POMDP subproblems.

The problem of unreliable resource allocation is discussed in [Casta˜n´on and Wohletz,

2002,Castanon and Wohletz, 2009] in which a pool of M resources is assigned to complete

N failure-prone tasks over several stages using an SDP formulation. Casta˜n´on proposes

a receding-horizon control approach to solve a relaxed DP problem that has an execution

time nearly linear in the number of tasks involved, however this work does not handle a

partially observable state.

Most approaches for dynamic feedback control are limited in application to problems

with a small number of sensor-action choices and simple constraints because the algo-

rithms must enumerate and evaluate the various control actions. In [Casta˜n´on, 1997],

combinatorial optimization techniques are integrated into a DP formulation to obtain

approximate SDP algorithms that extend to large numbers of sensor actions. Subsequent

work in [Casta˜n´on, 2005b] derives an SDP formulation using partially observed Markov

decision processes (POMDPs) and obtains a computable lower bound to the achievable

performance of feedback strategies for complex multi-sensor, SM problems. The lower](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-33-320.jpg)

![12

bound is obtained by a convex relaxation of the original combinatorial POMDP using

mixed strategies and averaged constraints. However, the results in [Casta˜n´on, 2005b]

do not specify algorithms with performance close to the lower bound (see Section 2.2).

This dissertation describes such an algorithm in Ch. 3 and then proposes theoretical

extensions to this algorithm in Ch. 4.

2.1.5 Human-Robot Interactions and Human Factors

The use of simulation as a technique to explore the best means of Human-Robot Inter-

action (HRI) in teams with multiple robots per human is the subject of [Dudenhoeffer

et al., 2001]. Questions of human situational awareness, mode awareness (what the

robot is currently doing), and mental model formulation are discussed.

In [Raghunathan and Baillieul, 2010], a search game involving the identification

of roots of random polynomials is presented. The paper analyses the search versus

exploration trade-off made by players and develops Markov models that emulate the

style of play of the 18 players involved in the experiments indistinguishably w.r.t. a

performance metric.

The SAGAT tool for measuring situational awareness has gained wide acceptance in

the literature [Endsley, 1988]. This tool is important for estimating an operator’s ability

to adequately control a team of robots and avoid mishaps.

In the M.S. thesis of [Anderson, 2006], various hierarchical control structures are

described for the human control of multiple robots. A game of tag is played inside

a maze by two teams of three robots controlled at 5 levels of autonomy, and various

metrics for human and robot performance are studied. Robots in this work are either

tele-operated or move myopically, and sensor measurements are noiseless within a certain

range.

In [Scholtz, 2002], possible HRI interactions are divided up into three categories, and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-34-320.jpg)

![13

it is speculated that each category of interaction requires different types of information

and a different interface. This work suggests that a system with multiple levels of

autonomy requires different kinds kind of interfaces according to its mode of operation

and needs to be able to transition between them without confusing the human operator.

In [Cummings et al., 2005], Cummings discusses a list of issues that need to be

addressed to achieve the military’s vision for Network Centric Warfare (NCW). The

author states that to improve system performance, systems must move from a paradigm

of Management by Consent (MBC) to Management by Exception (MBE).

A system for predicting human performance in tasking multiple robotic vehicles is

discussed in [Crandall and Cummings, 2008]. Human behavior is predicted by generating

several stochastic models for 1) the amount of time humans need to issue commands

and 2) the amount of time humans need to switch between tasks. Several performance

metrics are also presented for situational awareness, for the effectiveness of an operator’s

communications with a robot, and for the success of robot behavior while untasked.

These references for HRI focus on human situational awareness, performance metrics,

and various control strategies for human control of automata in simple environments.

These references do not investigate the question of an optimal means of HRI in a semi-

autonomous system in which robots with noisy, resource-constrained sensors are used to

explore an unknown, partially-observable and dynamic environment using non-myopic

and adaptive search strategies.

2.1.6 Summary of Background Work

As the above discussion indicates, the research to date has focused on only parts of

the problem of interest in this dissertation. The methods used in the existing body

of research need to be merged and unified in an intelligent fashion such that a semi-

autonomous search, plan, and execution system is created that behaves cohesively and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-35-320.jpg)

![14

in a non-myopic, adaptive fashion.

In this dissertation, we develop and implement algorithms for the efficient compu-

tation of adaptive SM strategies for complex problems involving multiple sensors with

different observation modes and large numbers of potential object locations. The al-

gorithms we present are based on using the lower bound formulation from [Casta˜n´on,

2005b] as an objective in a RH optimization problem and on developing techniques for

obtaining feasible sensing actions from (generally infeasible) mixed strategy solutions.

These algorithms support the use of multiple, multi-modal, resource-constrained, noisy

sensors operating in an unknown environment in a search and classification context.

The resulting near-optimal, adaptive algorithms are scalable to large numbers of tasks,

and suitable for real-time SM.

2.2 Sensor Management Formulation and Previous Results

In this section, we discuss the SM stochastic control formulation and results presented

in [?] which serve as the starting point for our work in subsequent chapters. We extend

the notation of [?] to include multiple sensors and additional modes such as search.

2.2.1 Stationary SM Problem Formulation

Assume there are a finite number of locations 1, . . . , N, each of which may have an object

with a given type, or which may be empty. Assume that there is a set of S sensors, each

of which has multiple sensor modes, and that each sensor can observe one and only one

location at each time with a selected mode. This assumption can be relaxed, although

it introduces additional complexity in the exposition and the computation.

Let xi ∈ {0, 1, . . . , D} denote the state of location i, where xi = 0 if location i

is unoccupied, and otherwise xi = k > 0 indicates location i has an object of type

k. Let πi(0) ∈ ℜD+1

be a discrete probability distribution over the possible states for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-36-320.jpg)

![16

observe, denoted by Os ⊆ {1, . . . , N}. A sensor action by sensor s at stage t is a pair:

us(t) = (is(t), ms(t)) (2.1)

consisting of a location to observe, is(t) ∈ Os, and a mode for that observation, ms(t).

Sensor measurements by sensor s with mode m at stage t, ys,m(t) are modeled as be-

longing to a finite set ys,m(t) ∈ {1, . . . , Ls}. The conditional probability of the measured

value is assumed to depend on the sensor s, sensor mode m, location i and on the true

state at the location, xi, but not on the states of other locations. Denote this condi-

tional probability as P(ys,m(t)|xi, i, s, m). We assume that this conditional probability

given xi is time-invariant, and that the random measurements ys,m(t) are conditionally

independent of other measurements yσ,n(τ) given the states xi, xj for all sensors s, σ

and modes m, n provided i = j or τ = t.

Each sensor has a limited quantity of Ri resources available for measurements over

the T stages of time. Associated with the use of mode m by sensor s on location i is

a resource cost rs(us(t)) to use this mode, representing power or some other type of

resource required to use this mode from this sensor.

T−1

t=0

rs(us(t)) ≤ Rs ∀ s ∈ [1, . . . , S] (2.2)

This is a hard constraint for each realization of observations and decisions.

Let I(t) denote the history of past sensing actions and measurement outcomes up to

and including stage t − 1:

I(t) = {(us(τ), ys,m(τ)), s = 1, . . . , S; τ = 0, . . . , t − 1}

As is frequently the case when working with POMDPs, we make use of the idea of the

information history as a sufficient statistic for the state of the system/world x.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-38-320.jpg)

![17

Under the assumption of conditional independence of measurements and indepen-

dence of individual states at each location, the joint probability π(t) = P(x1 = k1, x2 =

k2, . . . , xN = kN |I(t)) can be factored as the product of belief-states (marginal condi-

tional probabilities) for each location. Denote the conditional probability (belief-state)

at location i as πi(t) = p(xi|I(t)). The probability vector π(t) is a sufficient statistic for

all information that is known about the state of the N locations up until time t.

When a sensor measurement is taken, the belief-state π(t) is updated according to

Bayes’ Rule. A measurement of location i with the sensor-mode combination us(t) =

(i, m) at stage t that generates observable ys,m(t) updates the belief-vector as:

πi(t + 1) =

diag{P(ys,m(t)|xi = j, i, s, m)}πi(t)

1T

diag{P(ys,m(t)|xi = j, i, s, m)}πi(t)

(2.3)

where 1 is the D + 1 dimensional vector of all ones. Eq. 2.3 captures the relevant

information dynamics that SM controls. For generality, the index i in the likelihood

function specifies that the sensor statistics could vary on a location-by-location basis.

Of prime importance is the fact that using π(t) as a sufficient statistic along with

Eq. 2.3, we are able to combine a priori probabilities represented by π(t) with conditional

probabilities given by sensor measurements in order to form posterior probabilities,

π(t + 1), in recursive fashion: beliefs can be maintained and propagated.

In addition to information dynamics, there are resource dynamics that characterize

the available resources at stage t. The dynamics for sensor s are given as:

Rs(t + 1) = Rs(t) − rs(us(t)); Rs(0) = Rs (2.4)

These dynamics constrain the admissible decisions by a sensor, in that it can only use

modes that do not use more resources than are available.

An adaptive feedback strategy is a closed-loop policy or decision-making rule that

maps collected information sets up until stage t, i.e. the sets Ii(τ) ∀ i ∈ [1, . . . , N], τ ∈](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-39-320.jpg)

![18

[0, . . . , t − 1] to choose actions for stage t: γ : I(t) → U(t). Define a local strategy, γi,

as an adaptive feedback strategy that chooses actions for location i purely based on the

information sets Ii(t), which is to say based purely on the history of past actions and

observations specific to location i.

Given the final information, I(T), the quality of the information collected is measured

by making an estimate of the state of each location i given the available information.

Denote these estimates as vi ∀ i = 1, . . . , N. The Bayes’ cost of selecting estimate vi

when the true state is xi is denoted as c(xi, vi) ∈ ℜ with c(xi, vi) ≥ 0. The objective of

the SM stochastic control formulation is to minimize:

J =

N

i=1

E[c(xi, vi)] (2.5)

by selecting adaptive sensor control policies and final estimates subject to the dynamics

of Eq. 2.3 and the constraints of Eq. 2.2 and Eq. 2.4.

This problem was solved using dynamic programming in [Casta˜n´on, 2005a] as follows:

Define the optimal value function V (π, R, t) that is the optimal solution to Eq. 2.5

subject to Eq. 2.2 and Eq. 2.4 when the initial information is π, and R is the vector

of current resource levels. Let R = [R1 R2 . . . RS]T

. Define πij as the jth

component

of the probability vector associated with location i. The value function is defined on

SN

× ℜS

+. Let U represent the set of all possible sensor actions and define U(R) ⊂ U

as the set of feasible actions with resource level R. The value function V (π, R, t) must

be recursively related to V (π, R, t + 1), its value one time step earlier, according to

Bellman’s Equation [Bellman, 1957]:

V (π, R, t + 1) = min

N

i=1

min

vi∈X

j=0,...,D

c(j, vi)πij, (2.6)

min

u∈U(R)

E

y

{V (T(π, u, y), R − Ru, t)}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-40-320.jpg)

![19

where Ru = [r1(u1(t)) r2(u2(t)) . . . rS(uS(t))]T

and T(.) is an operator describing the

belief dynamics. T is the identity mapping for information states πj(t) ∀ j except for

{j | j = is ∀ s ∈ [1, . . . , S]}, the set of sensed locations. For a sensed location i, T maps

πi(t) to πi(t + 1) with Eq. 2.3. The expectation in Eq. 2.6 is given by:

E

y

{V (T(π, u, y), R − Ru, t)} =

y∈Ys,m ∀ s

P(y|I(k), u)V (T(π, u, y), R − Ru, t)

where Ys,m is the (discrete) set of possible observations (symbols) for sensor s with

mode m, and y is a vector of measurements with one measurement per sensor. (The

mode m for each sensor s is determined by the vector-action u in the minimization).

The minimization is done over S dimensions because there are S sensors.

To initialize the recursion, the optimal value function when the number of stages to

go t is zero is determined by choosing the classification decision vi without any additional

measurements, as

V (π, R, 0) =

N

i=1

min

vi∈X

j=0,...,D

c(j, vi)πij (2.7)

Note that this minimization can be done independently for each location i. The optimal

value of Eq. 2.5 can be computed using Eq. 2.6 - Eq. 2.7.

The problem with the DP equation Eq. 2.6 as it currently stands is that whereas the

measurement and classification costs of the N locations in the problem initially start

off decoupled from each other (c.f. Eq. 2.7), the DP recursion does not preserve the

decoupling from one stage to the next. Therefore in general the best choice of action for

location i with t stages-to-go will depend on the amount of resources from each of the

different sensors that have been expended on other locations during the previous stages.

This leads to a very large POMDP problem with a combinatorial number of actions to

consider and an underlying belief-state of dimension (D + 1)N

that is computationally

intractable unless there are few locations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-41-320.jpg)

![20

In [Casta˜n´on, 2005b], the above problem is replaced by a simpler problem that

provides a lower bound on the optimal cost, by expanding the set of admissible strategies,

replacing the constraints of Eq. 2.2 with “soft” constraints:

E[

T−1

t=0

rs(us(t))] ≤ Rs ∀ s ∈ [1 . . . S] (2.8)

Note that every admissible strategy that satisfies Eq. 2.2 also satisfies Eq. 2.8. After

relaxing the resource constraints, there is just one constraint per sensor (instead of one

constraint for every possible realization of actions and observations per sensor). These

constraints are constraints on the average resource use one would expect to spend over

the planning horizon.

To solve the relaxed problem, [Casta˜n´on, 2005b] proposed incorporation of the soft

constraints in Eq. 2.8 into the objective function using Lagrange multipliers λs for each

sensor s and using Lagrangian Relaxation. Now the measurement and classification costs

for a pair of locations are only related through the values of the Lagrange multipliers

associated with the sensors they use in common. Therefore given the price of time for

the set of sensors that will be used in the optimal policy to make measurements on a

pair of locations, the classification and measurement costs for those two locations are

decoupled in expectation! Once we can partition resources between a pair of locations,

we can do so for N locations. The augmented objective function is:

¯Jλ = J +

T−1

t=0

S

s=1

λs E[rs(us(t))] −

S

s=1

λsRs (2.9)

Define an admissible strategy, γ, as a function which maps an information state,

π(t), to a feasible measurement action (or to a null action if sufficient resources are

unavailable). Define Γ as the set of all possible γ. Because the measurements and

possible sensor actions are finite-valued, the set of possible SM strategies Γ is also finite.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-42-320.jpg)

![21

Let Q(Γ) denote the set of mixed strategies that assign probability q(γ) to the choice of

strategy γ ∈ Γ.

A key result in [Casta˜n´on, 2005b] was that when the optimization of Eq. 2.9 was

done over mixed strategies for given values of Lagrange multipliers, λs, optimization

problem in Eq. 2.9 decoupled into independent POMDPs for each location, and the

optimization could be performed using local feedback strategies, γi, for each location i.

Write ΓL for the set of all local feedback strategies. These POMDPs have an underlying

information state-space of dimension D + 1, corresponding to the number of possible

states at a single location, and can be solved efficiently. Decomposition is essential to

make the problem tractable.

The pair of figures Fig. 2·2 and Fig. 2·3 demonstrate what a stereotypical POMDP

solution (for a toy problem) looks like. These figures describe the optimal set of solution

hyperplanes and the optimal policy for SM on a set of locations given a vector of prices

for resource costs (i.e. assuming for the moment that we already know what the optimal

resource prices are). The brown and magenta hyperplanes (nodes 2 and 6 w.r.t. Fig. 2·3

are very nearly parallel to the neighboring hyperplanes and therefore two of the three

hyperplanes with node id’s 1–3 are very nearly redundant (dominated) and the same

goes for node id’s 5–7. The smaller the extent of a hyperplane in the concave (for cost

functions) hull of the set of hyperplanes, the less role it has to play in the optimal

value function. In this example the cost of the ‘Mode1’ action was 0.1 units and that

of ‘Mode2’ was 0.18 units. If the ‘Mode2’ cost is changed to 0.2 units then there

are only 7 hyperplanes in the optimal set of hyperplanes (i.e. the value function) and

‘Mode2’ is not used at all. These results are relative to the prior probability and sensor

statistics. The alpha vectors (i.e. hyperplane coefficients) and actions associated with

each hyperplane (equivalently decision-tree node) can be seen in the inset below the

value function. The state enumeration was X={‘non-military’,‘military’}. The alpha](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-43-320.jpg)

![22

vector coefficients give the classification + measurement cost of a location having each

one of these states w.r.t. this enumeration.

In Fig. 2·3, assume hypothesis ‘H2’ corresponds to ‘Declare military vehicle’ and

‘H1’ is the null hypothesis (‘Declare non-military vehicle’). In this policy the arrows

leaving each node on top represent observation ‘y1’ (‘non-military’), and the arrows on

bottom represent ‘y2’ (‘military’). The 9 nodes on the left of this policy correspond

to the 9 hyperplanes that make up Fig. 2·2. If there had been more than two possible

actions and two possible observations, then after a few stages there could easily have

been thousands of distinct nodes in the initial stage! This figure uses a model with a

dummy/terminal capture state, so it is possible to stop sensing at any time.

The use of two states, one sensor with two modes, two observations (the same type of

observations for both modes) for a horizon 5 (4 sensing actions+classification) POMDP

results in 9 hyperplanes based on the particular cost structure used: ‘Mode1’ costs

0.1 units and ‘Mode2’ costs 0.18 units. False alarms (FAs) and Missed detections (MDs)

each cost 1 unit. For problems with several sensors, 4 possible states and 3 modes

per sensor with 3 possible observations, there are frequently on the order of 500–1000

hyperplanes for a horizon 5 POMDP. Whereas originally this work was done using the

Witness Algorithm in a modified version of pomdp-solve-5.3 [Cassandra, 1999], this

algorithm is slow when solving 1000’s (later millions) of POMDPs in a loop. Therefore,

by default we use the Finite Grid algorithm (PBVI) within our customized version of

pomdp-solve-5.3 with 500–1000 belief-points to solve POMDPs. This allows a POMDP

of this size to be solved within about 0.2 sec on a single-core, Intel P4, 2.2 GHz, Linux

machine.

There is a trade-off between correctly detecting objects and engendering false alarms.

Fig. 2·4 illustrates how the overall classification cost increases as the ratio of the MD:FA

cost increases (from 1:1 through 80:1) for 3 resource levels {300, 500, 700} according to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-44-320.jpg)

![24

two cases: in the first case the resources are all available to a single sensor that supports

two modes of operation {‘mode1’, ‘mode2’}, and in the second case the resources are

equally divided between two identical sensors that each support the same two modes of

operation. Partitioning resources in this way adds an additional constraint that increases

classification cost. We also observe that the larger the quantity of resources available,

the larger the discrepancy between the S = 1, M = 2 case and the S = 2, Ms = 1 ∀ s

case.

In order to have meaningful POMDP solutions, we must have a way of coordinating

the sensing activities between various locations. Lagrange multipliers and Lagrangian

Relaxation provide this coordinating mechanism. Writing our policies for SM in terms

of mixed strategies allows linear programming techniques to be used for Lagrangian

Relaxation. To this end, we write Eq. 2.9 in terms of mixed strategies:

˜J∗

λ = min

γ∈Q(ΓL)

E

γ

N

i=1

c(xi, vi) +

T−1

t=0

S

s=1

λsrs(us(t)) −

S

s=1

λsRs (2.10)

where the strategy γ maps the current information state π(t) to the choice of us(t) ∀ s.

At stage T the strategy γ also determines the classification decisions vi ∀ i. On account

of the fact that we chose a relaxed form of resource constraint in Eq. 2.2, we know that

the actual optimal cost must be lower bounded by Eq. 2.10 because we have expanded

the space of feasible actions. This identification leads to the inequality:

J∗

≥ sup

λ1,...,λS≥0

˜J∗

λ1,...,λS

(2.11)

As shown in [Casta˜n´on, 2005a], Eq. 2.11 is the dual of the LP:

min

q∈Q(ΓL)

γ∈ΓL

q(γ) E

γ

[J(γ)] (2.12)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-46-320.jpg)

![26

γ∈ΓL

q(γ) E

γ

N

i=1

T−1

t=0

rs(us(t)) ≤ Rs ∀ s ∈ [1, . . . , S] (2.13)

γ∈ΓL

q(γ) = 1 (2.14)

where we have one constraint for each of the S sensor resource pools and an additional

simplex constraint in Eq. 2.14 which ensures that q ∈ Q(ΓL) forms a valid probability

distribution.

This is a large LP, where the number of possible variables are the strategies in

ΓL. However, the total number of constraints is S + 1, which establishes that optimal

solutions of this LP are mixtures of no more than S + 1 strategies. Thus, one can use a

Column Generation approach [Gilmore and Gomory, 1961,Dantzig and Wolfe, 1961,Yost

and Washburn, 2000] to quickly identify an optimal mixed strategy that solves the relaxed

(i.e. approximate) form of our SM problem. (See Appendix A.3 for an overview of

Column Generation). To use Column Generation with the LP formulation Eq. 2.12 -

Eq. 2.14, we break the original problem hierarchically into two new sets of problems

that are called the master problem and subproblems. There is one POMDP subproblem

for each location. The master problem consists of identifying the appropriate values of

the Lagrange multipliers, λs ∀ s, to determine how resources should be shared across

locations, and the subproblems consist of using these Lagrange multipliers to compute

the expected resource usage and expected classification cost for each of the N locations.

See Fig. 2·5 for a pictorial representation.

Column Generation works by solving Eq. 2.12 and Eq. 2.13, restricting the mixed

strategies to be mixtures of a small subset Γ′

L ⊂ ΓL. The solution of the restricted LP

has optimal dual prices λs, s = 1, . . . , S. Using these prices, one can determine a corre-

sponding optimal pure strategy by minimizing Eq. 2.9, which the results in [Casta˜n´on,

2005b] show can be decoupled into N independent optimization problems, one for each

location. Each of the subproblems is solved as a POMDP using standard algorithms,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-48-320.jpg)

![27

Figure 2·5: Schematic showing how the master problem coordinates the ac-

tivities of the POMDP subproblems using Column Generation and Lagrangian

Relaxation. After the master problem generates enough columns to find the

optimal values for the Lagrange multipliers, there is no longer any benefit to

violating one of the resource constraints and the subproblems (with augmented

costs) are decoupled in expectation.

such as Point-Based Value Iteration (PBVI), Appendix A.2 [Pineau et al., 2003], to de-

termine the best pure strategy γ1 for these prices. Solving all of the subproblems allows a

new column to be generated by providing values for the expected classification cost and

expected resource utilization for a given set of sensor prices λs; these values become the

coefficients in the new column in the (Revised) Simplex Tableau of the master problem.

The column that is generated will be a pure strategy that is not already in the basis of

the LP (or else the master problem would have converged). If the best pure strategy, γ1,

for the prices, λs ∀ s ∈ [1, . . . , S], is already in the set Γ′

L, then the solution of Eq. 2.12

and Eq. 2.13 restricted to Q(Γ′

L) is an optimal mixed strategy over all of Q(ΓL), and

the Column Generation algorithm terminates. Otherwise, the strategy γ1 is added to

the admissible set Γ′

L, and the iteration is repeated. The solution to this algorithm is

a set of mixed strategies that achieve a performance level that is a lower bound on the

original SM optimization problem with hard constraints.

2.2.2 Addressing the Search versus Exploitation Trade-off

As one contribution of this dissertation, we address how to non-myopically trade-off be-

tween spending time searching for objects versus spending time acting on them. This is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-49-320.jpg)

![28

P(y1,1(t)|xi, u1(t)) = P(y1,2(t)|xi, u2(t)) = P(y1,3(t)|xi, u3(t)) =

empty

car

truck

SAM

0

B

B

B

B

B

@

0.92 0.04 0.04

0.08 0.46 0.46

0.08 0.46 0.46

0.08 0.46 0.46

1

C

C

C

C

C

A

o1 o2 o3

0

B

B

B

B

B

@

0.95 0.03 0.02

0.05 0.85 0.10

0.05 0.10 0.85

0.05 0.10 0.85

1

C

C

C

C

C

A

o1 o2 o3

0

B

B

B

B

B

@

0.97 0.02 0.01

0.02 0.95 0.03

0.02 0.90 0.08

0.02 0.03 0.95

1

C

C

C

C

C

A

o1 o2 o3

Table 2.1: Example of expanded sensor model for an SEAD mission

scenario where the states are {‘empty’, ‘car’, ‘truck’, ‘SAM’} and the

observations are ys,m = {o1 = ‘see nothing’, o2 = ‘civilian vehicle’, o3

= ‘military vehicle’} ∀ s, m. This setup models a single sensor with

modes {u1 = ‘search’, u2 = ‘mode1’, u3 = ‘mode2’} where mode2 by

definition is a higher-quality mode than mode1. Using mode1, trucks can

look like SAMs, but cars do not look like SAMs.

an easy generalization to make: object confusion matrices can be used to allow inferenc-

ing based on detection only. To accomplish this, we augment the sensor model used in

example of [Casta˜n´on, 2005a] with a ‘search’ action that supports a low-res mode of op-

eration (with low resource demand) designed for object detection but incapable of object

classification. Our sensor observation models can be made non-informative w.r.t. object

type by setting the conditional probability of an observation for each type of object to be

the same as in Table 2.1. As a simple starting point for the new sensor model, we consider

three possible values of observations : {o1 = ‘see nothing’, o2 = ‘uninteresting object’,

o3 = ‘interesting object’} that have known statistics and are the result of pre-processing

and thresholding sensor data. The ‘search’ action effectively returns the joint probability

of P(o2 ∩ o3|xi, u1).

2.2.3 Tracing Decision-Trees

One hindrance is that the hyperplanes given by a POMDP solver that represent the

expected cost-to-go are in terms of total cost. In order to create a new column, it is

necessary to separate out the classification cost from the measurement costs. This pro-

cess is best illustrated with an example. Consider Fig. 2·6. This figure is an illustration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-50-320.jpg)

![29

of “tracing” or “walking” a POMDP decision-tree solution to calculate expected clas-

sification costs and resource utilizations for a subproblem. The states in this example

are indexed as {‘military’, ‘truck’, ‘car’, ‘empty’}. The dot-product of the probability

vector for the current information state, in this example π(0) = [0.02 0.06 0.12 0.80]T

,

with the best hyperplane returned by Value Iteration (or the approximation PBVI)

gives the total cost for location i: Ji,total = Ji,measure +Ji,classify, from which we can calcu-

late the subproblem classification cost, Ji,classify, once we subtract out its measurement

cost, Ji,measure. To subtract out the measurement cost, we must recursively traverse the

decision-tree and sum up the (expected) cost of each potential measurement action. The

probability mixture weights in the expected cost of each action are given by the obser-

vation probabilities P(ys,m(t)|πi(t), u(t)), where u(t) is the sensor action taken. For the

particular initial probability of π(0), only actions in the set {‘wait’, ‘search’} are part

of the optimal solution (for simplicity of illustration). The numbers in blue represent

the conditional likelihood of an observation occurring, and the color of each node rep-

resents the optimal choice of action for that information state (and nearby information

states): {white=‘wait’, aqua=‘search’}. Given this decision-tree that represents the op-

timal course of action for the information state π(0), the set of possible future beliefs

and the relative likelihood of each belief occurring are shown. The possible beliefs and

likelihoods display their respective observation histories up to time t using the conven-

tion o = {y(0), . . . , y(t−1)}. In this example false alarm and missed detection costs are

equal (FA=MD), and the (time-invariant) likelihoods for the ‘search’ action are:

P(ysearch(t)|xi, ‘search’) =

0.08 0.46 0.46

0.08 0.46 0.46

0.08 0.46 0.46

0.92 0.04 0.04

In this matrix, the states xi vary along the rows, and the observations {‘o0’, ‘o1’, ‘o2’} (for

{‘see nothing’, ‘see non-military vehicle’, ‘see military vehicle’}) vary across the columns.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-51-320.jpg)

![30

All indices are 0-based. There were 3 observations (which in general implies three child

nodes for every node in the decision-tree) for some actions, but the search action has a

uniform observation probability over all non-empty observations (all observations except

‘o0’), and therefore the latter two future node indices for search nodes (nodes that specify

search actions) are always the same. (This keeps the example tractable). For a ‘wait’

action, all three future nodes are the same because there is only one possible future belief-

state. The green terminal classification (‘declaration’) node represents the decision that

a location contains a benign object (‘truck’, ‘car’) and the gray declaration node that the

location is ‘empty’. The nodes are labeled using the scheme: ‘[nodeId nextNodeId[o0]

nextNodeId[o1] nextNodeId[o2]’, so for the root node (stage 0, node 0) the next node will

be (stage 1, node 4) if the observation is o0, (stage 1, node 1) if the observation is o1, and

again (stage 1, node 1) for observation o2 because a search action can not discriminate

object type. The declaration nodes have no future nodes, which is indicated with ‘X’

characters. Notice there are two possible information states (beliefs) for π(2) at nodeId 0

during the second-to-last stage, and therefore the conditional observation probabilities

at this node are path-dependent (the nodes represent a convex region of belief-space,

they do not represent a unique probability vector). The red star and black box in the

figure indicate the two different possible beliefs (and therefore the two different possible

sets of observation likelihoods) for this node. The vector πnew(1) represents the future

belief-state after one time interval if no action is taken. In other words the state is

non-stationary in this example and in fact a HMM model was imposed on the state of

each location. The HMM has an arrival probability (chance of leaving the ‘empty’ state)

at each stage of 5%: the probability of a location being empty goes from 80% to 76% in

one stage (0.05 × 0.80 = 0.76), and this probability mass diffuses elsewhere (increases

the chance of state ‘military’).

One caveat w.r.t. the software package we used (an extensively modified version of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-52-320.jpg)

![31

Tony Cassandra’s pomdp-solve-5.3 [Cassandra, 1999]) that comes into play with a time-

varying state is that an observation at stage t (undesirably) refers to the system state

at time t+1. This is the convention used in the robotics community but is not desirable

in an SM context: it’s anti-causal. There is no difference if the state is stationary. We

will pick up this topic of non-stationarity again in the next section and then as one of

the main topics of Ch. 4.

Each possible terminal belief-state is indicated along with the associated proba-

bility of classification error in the lower-right corner. By way of example, while the

P(error|π(3;o=0,0,0)) = 0.0052, the expected contribution of this error to the terminal

classification cost is even smaller because the likelihood of this particular outcome is

the joint probability of the associated observations: P(y0 = 0, y1 = 0, y2 = 0) = P(y0 =

0)P(y1 = 0)P(y2 = 0) = 0.7184∗0.8567∗0.8724 (the numbers in blue along this realiza-

tion of the decision-tree). The variables in the conditioning were suppressed for brevity.

Unfortunately, walking the decision-trees to back out classification costs is rather slow

(recursive function calls) with large trees, requiring on the order of 15% of the compu-

tational time in simulations with horizon 6 plans (PBVI took around 80%), however at

least this operation is parallelizable, and the PBVI algorithm is parallelizable as well!

As a slightly more complex example of a set of POMDP solutions and what tracing

decision-trees entails, consider Fig. 2·7 and Fig. 2·8 which show a pair of decision-trees

for a horizon 6 scenario with D = 3 and Ms = 3 (plus a ‘wait’ action). The state

‘empty’ has been added to X and a ‘search’ mode has been added to the action space.

The ‘search’ mode is able to quickly detect the presence or absence of an object but

completely unable to specify object type. In addition, an HMM has been used instead

of having the state be stationary such that the model allows for a non-zero probability

of object arrivals from one stage to the next. This example uses an object arrival

probability of 5% / stage. It is interesting to note the situations in which the optimal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-53-320.jpg)

![33

Figure 2·7: Strategy 1 (mixture weight=0.726). πi(0) = [0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1]’

∀ i ∈ [0, . . . , 9], πi(0) = [0.80 0.12 0.06 0.02]T

∀ i ∈ [10, . . . , 99]. The first 10

objects start with node 5, the remaining 90 start with node 43. The notation

[i Ni0 Ni1 Ni2] indicates the next node/action from node i as a function of

observing the 0th, 1st or 2nd observations respectively.

strategy is to wait to act versus to gain as much information as possible with the time

available.

2.2.4 Violation of Stationarity Assumptions

At first glance, using a HMM state model with arrival probabilities, as in Fig. 2·6,

seems to violate our stationarity assumptions that allowed us to decompose the original

problem into one in which we have parallel virtual time-lines happening at each location

and where we did not need to worry about the sequencing of events between these

locations. Given stationarity, the order in which locations are sensed does not matter.

We notice that the same thing is true for a HMM with arrival probabilities because

having an object arrive at a location does not influence the optimal choice of sensing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-55-320.jpg)

![34

Figure 2·8: Strategy 2 (mixture weight=0.274) πi(0) = [0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1]’ ∀ i ∈

[0, . . . , 9], πi(0) = [0.80 0.12 0.06 0.02]T

∀ i ∈ [10, . . . , 99]. The first 10 objects

start with node 6, the remaining 90 start with node 18.

actions at that location in the past when the location was empty. If a location is

empty, there is no sensing to be done. An arrival only affects the best choices of sensing

action for that location in the future, and we replan every round. Therefore we can

still decouple sensing actions across locations when we have arrivals. The problem in

developing a model for a time-varying state is how to handle object departures. If an

object departs (a location becomes empty), now the best choice of previous actions for

that location are affected retroactively.

2.3 Column Generation And POMDP Subproblem Example

In this section we present an example of the Column Generation algorithm and POMDP

algorithms discussed previously. In this simple example we consider 100 objects (N=100),

2 possible object types (D=2) with X = {‘non-military vehicle’, ‘military vehicle’}, and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-56-320.jpg)

![35

2 sensors that each have one mode (S = 2 and Ms = 1 ∀ s ∈ {1, 2}). Sensor s actions

have resource costs: rs, where r1 = 1, r2 = 2. Sensors return 2 possible observation

values, corresponding to binary object classifications, with likelihoods:

P(y1,1(t)|xi, u1(t)) P(y2,1(t)|xi, u2(t))

0.90 0.10

0.10 0.90

0.92 0.08

0.08 0.92

where the (j, k) matrix entry denotes the likelihood that y = k if xi = j. The second

sensor has 2% better performance than the first sensor but requires twice as many

resources to use. Each sensor has Rs = 100 units of resources, and can view each

location. Each of the 100 locations has a uniform prior of πi = [0.5 0.5]T

∀ i. For the

performance objective, we use c(xi, vi) = 1 if xi = vi, and 0 otherwise, so the cost is

1 unit for a classification error.

Table 2.2 demonstrates the Column Generation solution process. The first three

columns are initialized by guessing values of resource prices and obtaining the POMDP

solutions, yielding expected costs and expected resource use for each sensor at those

resource prices. A small LP is solved to obtain the optimal mixture of the first three

strategies γ1, . . . , γ3, and a corresponding set of dual prices. These dual prices are used

in the POMDP solver to generate the fourth column γ4, which yields a strategy that is

different from that of the first 3 columns. The LP is re-solved for mixtures of the first

4 strategies, yielding new resource prices that are used to generate the next column. This

process continues until the solution using the prices after 7 columns yields a strategy

that was already represented in a previous column, terminating the algorithm. The

optimal mixture combines the strategies of the second, fifth and sixth columns. When

the master problem converges, the optimal cost, J∗

, for the mixed strategy is 5.95 units.

The resulting decision-trees are illustrated in Fig. 2·9, where branches up indicate

measurements y = 1 (‘non-military’) and down y = 2 (‘military’). The red and green](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-57-320.jpg)

![41

• str1: Select the pure strategy with maximum probability.

• str2: Randomly select a pure strategy per location according to the optimal mix-

ture probabilities.

• str3: Select the pure strategy with positive probability that minimizes the expected

sensor resource use over all sensors (and leaves resources for use in future stages).

The column gen simulator that we have developed also supports two other methods

for converting mixed strategies to sensing actions:

• str4: Select the pure strategy that minimizes classification cost.

• str5: Randomly select a single pure strategy for all locations jointly according to

the optimal mixture probabilities.

However these latter two methods for RH control were deemed to be less useful and

therefore were not included in the fractional factorial design of experiments analysis.

The pure strategies that are selected for each location map the current information

sets, Ii(t) for location i, into a deterministic sensing action. ‘str1’ and ‘str3’ choose

the same pure strategy to use across all locations, but ‘str2’ chooses a pure strategy

on a location-by-location basis. Note that there may not be enough sensor resources

to execute the selected actions, particularly in the case where the pure strategy with

maximum probability is selected. To address this, we rank sensing actions by their

expected entropy gain [Kastella, 1996]:

Gain(us(t)) =

H(πi(t)) − Ey[H(πi(t + 1))|y, us(t)]

rs(us(t))

(3.1)

where Ey[] is the expected future entropy value. We schedule sensor actions in order

of decreasing expected entropy gain, and perform those actions at stage t that have

enough sensor resources to be feasible. We also use the Entropy Gain algorithm at the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-63-320.jpg)

![42

very end of a simulation when resources are nearly depleted, and the higher cost sensor

modes are no longer feasible, see Appendix B for more information. (When the horizon

is very short, the Entropy Gain algorithm is nearly-optimal, so this does not constitute

a significant performance limitation in our design).

The measurements collected from the scheduled actions are used to update the infor-

mation states πi(t + 1) using Eq. 2.3. The resources used by the actions are eliminated

from the available resources to compute Rs(t + 1) using Eq. 2.4. The RH algorithm

is then executed from the new information state/resource state condition in iterative

fashion until all resources are expended.

3.2 Simulation Results

In order to evaluate the relative performance of the alternative RH algorithms, we

performed a set of simulations. In these experiments, there were 100 locations, each of

which could be empty, or have objects of three types, so the possible states of location i

were xi ∈ {0, 1, 2, 3} where type 1 represents cars, type 2 trucks, and type 3 military

vehicles. Sensors can have several modes: a ‘search’ mode, a low resolution ‘mode1’ and

a high resolution ‘mode2’. The search mode primarily detects the presence of objects;

the low resolution mode can identify cars, but confuses the other two types, whereas the

high resolution mode can separate the three types. Observations are modeled as having

three possible values. The search mode consumes 0.25 units of resources, whereas the

low-resolution mode consumes 1 unit and the high resolution mode 5 units, uniformly

for each sensor and location. Table 3.1 shows the likelihood functions that were used in

the simulations.

Initially, each location has a state with one of two prior probability distributions:

πi(0) = [0.10 0.60 0.20 0.10]T

, i ∈ [1, . . . , 10] or πi(0) = [0.80 0.12 0.06 0.02]T

, i ∈

[11, . . . , 100]. Thus, the first 10 locations are likely to contain objects, whereas the other](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-64-320.jpg)

![45

plan is accounting for, — after doing multiple planning iterations. (A simulation may

re-plan 5+ times before resources are exhausted, but the bound was computed assuming

there will only be a maximum of two sensing opportunities per object for a horizon=3

problem). Obviously, the easily classified objects are ruled out of the competition for

sensor resources (their identities are decided upon) early in the simulation process,

and with every additional planning iteration, sensor resources are concentrated on the

remaining objects whose identities are uncertain. In this situation the approximate

sensor plan from the Column Generation algorithm does not match well with the way

events unfold, and the “bound” is not a bound. However, after choosing a horizon that

accounts appropriately for how many RH planning iterations there will be and how

many sensing opportunities will take place at each location, the bounds are tight.

In terms of which strategy is preferable for converting the mixed strategies to a pure

strategy, the results of Table 3.3 are unclear. For short planning horizons in the RH

algorithms, the preferred strategy appears to be to use the least resources (str3): because

planning with a longer horizon improves performance minimally, we find that using a RH

replanning approach with a short horizon in conjunction with a resource-conservative

planning strategy can be used to reduce computation time with limited performance

degradation. For the longer horizons, there was no significant difference in performance

among the three strategies we investigated.

In the next set of experiments, we compare the use of heterogeneous sensors that

have different modes available. In these experiments, the 100 locations are guaranteed

to have an object, so xi = 0 is not feasible. The prior probability of object type for

each location is πi(0) = [0 0.7 0.2 0.1]T

. Table 3.5 shows the results of experiments with

sensors that have all sensing modes, versus an experiment where one sensor has only

a low-resolution mode and the other sensor has both high and low-resolution modes.

The table shows the lower bounds predicted by the Column Generation algorithm, to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-67-320.jpg)

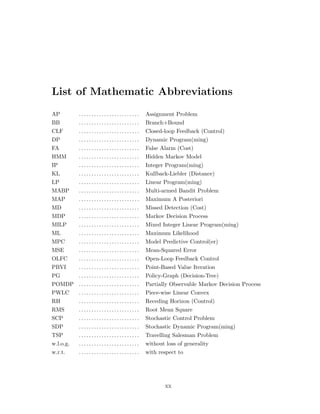

![46

MD = 1 MD = 5 MD = 10

Hor. 3 str1 str2 str3 str1 str2 str3 str1 str2 str3

Res 30 3.64 3.85 3.85 11.82 12.88 12.23 15.28 14.57 14.50

Res 50 2.40 2.80 2.43 6.97 6.93 7.84 10.98 9.99 10.45

Res 70 2.45 2.32 1.88 3.44 3.99 4.04 6.14 6.48 5.10

Hor. 4

Res 30 3.58 3.46 3.52 12.28 12.62 11.90 14.48 15.91 15.59

Res 50 2.37 2.21 2.33 7.44 7.44 7.20 9.94 9.28 10.65

Res 70 1.68 1.33 1.60 3.59 3.57 3.62 6.30 5.18 5.86

Hor. 6

Res 30 3.51 3.44 3.73 11.17 11.85 12.09 15.17 14.99 13.6

Res 50 2.28 2.11 2.31 7.29 8.02 7.70 10.67 10.47 11.25

Res 70 1.43 1.38 1.44 3.60 3.73 3.84 4.91 5.09 5.94

Table 3.3: Simulation results for 2 homogeneous, multi-modal sensors in

a search and classify scenario. str1: select the most likely pure strategy for

all locations; str2: randomize the choice of strategy per location according to

mixture probabilities; str3: select the strategy that yields the least expected

use of resources for all locations. See Fig. 3·2 - Fig. 3·4 for the graphical version

of this table.

MD

Horizon 3 1 5 10

Res[30, 30] 4.96 12.11 14.64

Res[50, 50] 4.09 8.79 11.16

Res[70, 70] 3.38 6.20 8.19

Horizon 4

Res[30, 30] 4.24 11.86 14.56

Res[50, 50] 3.09 6.72 9.50

Res[70, 70] 2.16 4.24 5.94

Horizon 6

Res[30, 30] 3.35 11.50 13.85

Res[50, 50] 2.21 6.27 9.40

Res[70, 70] 1.32 2.95 4.96

Table 3.4: Bounds for the simulations results in Table 3.3. When the horizon

is short, the 3 MPC algorithms execute more observations per object than were

used to compute the “bound”, and therefore, in this case, the bounds do not

match the simulations; otherwise, the bounds are good.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9f5467db-22a0-4b25-9f85-d66c2d62a6f8-160910233158/85/dissertation-68-320.jpg)

![47

1 2 3

0

5

10

15

FA:MD = 1 Bound = 4.960

E[J]

1 2 3

0

5

10

15

FA:MD = 5 Bound = 12.110

E[J]

1 2 3

0

5

10

15

FA:MD = 10 Bound = 14.640

E[J]

1 2 3

0

5

10

15

FA:MD = 1 Bound = 4.090

E[J]

1 2 3

0

5

10

15

FA:MD = 5 Bound = 8.790

E[J]

1 2 3

0

5

10

15

FA:MD = 10 Bound = 11.160

E[J]

1 2 3

0

5

10

15

FA:MD = 1 Bound = 3.380

E[J]

1 2 3

0

5

10

15

FA:MD = 5 Bound = 6.200

E[J]

1 2 3

0

5

10

15

FA:MD = 10 Bound = 8.190

E[J]

Horizon = 3

Resources =

60.0

Resources =

100.0

Resources =

140.0

Figure 3·2: This figure is the graphical version of Table 3.3 for horizon 3.

Simulation results for two sensors with full visibility and detection (X=’empty’,

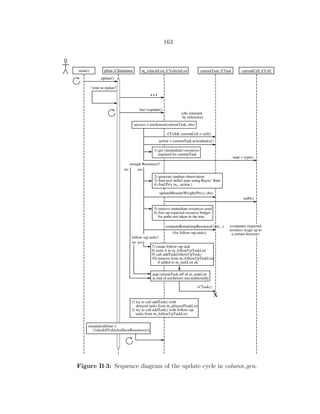

’car’, ’truck’, ’military’) using πi(0) = [0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1]T