This article discusses museum development and cultural policy in Latin America and the Caribbean over the past 10 years. It notes the diversity of cultures and political/economic systems in the region and how museums are being called on to play a major role in developing awareness of cultural heritage. A 1972 conference marked a turning point, promoting an "integral museum" approach focused on interdisciplinarity and relating heritage to society's present needs. Since then, museums have increasingly taken on the challenge of making heritage relevant to contemporary development. The article seeks perspectives from regional experts on progress, challenges, and cultural policy priorities regarding museums.

![Vol. XXXIV, No. 2 , 1982

Museidni, successor to Mauseìoii, is published

by the United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organization in Paris.

An international forum (quarterly) of

information and reflection on museums of all

kinds.

Authors are responsible for the choice and the

presentation of the facts contained in their articles

and for the opinions expressed therein, which are

not necessarily those of Unesco or the Editorial

Board of Nueum. Titles, introductory texts and

captions may be written by the Editor.

DIRECTOR

Percy Stulz

EDITORIAL BOARD

Chairman: Syed A. Naqvi

Editor: Yudhishthir Raj Isar

Editorial Assistant : Christine Wilkinson

ADVISORY BOARD

Om Prakash Agrawal, India

Fernanda de Camargo e Almeida-Moro,

Brazil

Chira Chongkol, Thailand

Joseph-Marie Essomba, President of

OMMSA

Gad de Guichen, Scientific Training

Assistant, ICCROM

Jan Jelinek, Czechoslovakia

Grace L. McCann Morley, Adviser, ICOM

Regional Agency in Asia

Luis Monreal, Secretary-General of ICOM, Correspondence concerning editorid inatten

ex-oficia should be addressed to the Editor (Division

Paul Perror, United States of America of Cultural Heritage, Unesco, 7 place de

Georges Henri Rivière, Permanent Adviser Fontenoy, 75700 Paris, France) who is

of ICOM always pleased to consider manuscripts for

Vitali Souslov, Union of Soviet Socialist publication but cannot accept liability for

Republics their custody or return. Authors are advised

to write to the Editor first.

Cover photo: Restoration of polychrome Pziblished texts inay be fieely rgrodaced aiid

wood sculpture at the restoration c h t r e in trmslated (excqt illustrations and when

Antigua Guatemala. ~~~odztctioti or trattslatioz rights a4e ruewed),

[P/joto: Alejandro Rojas Garcia.] provided that m~itiotiis made of the author

and source. Extracts may be quoted i f due

acknoudedgenzent is givm

Each issue: 2 8 F. Subscription rates

( 4 issues or corresponding double issues per

year): 100 F (1 year); 160 F (2 years). Correspondence concerning subscrjbtìoin

should be addressed to the Commercial

@Unesco 1982 Services Division, Office of the Unesco

Pritited iti swìtzerlaiid Press, Unesco, 7 place de Fontenoy,

Imprimeries Populaires de Genève 7 5 7 O0 Paris, .France.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-2-320.jpg)

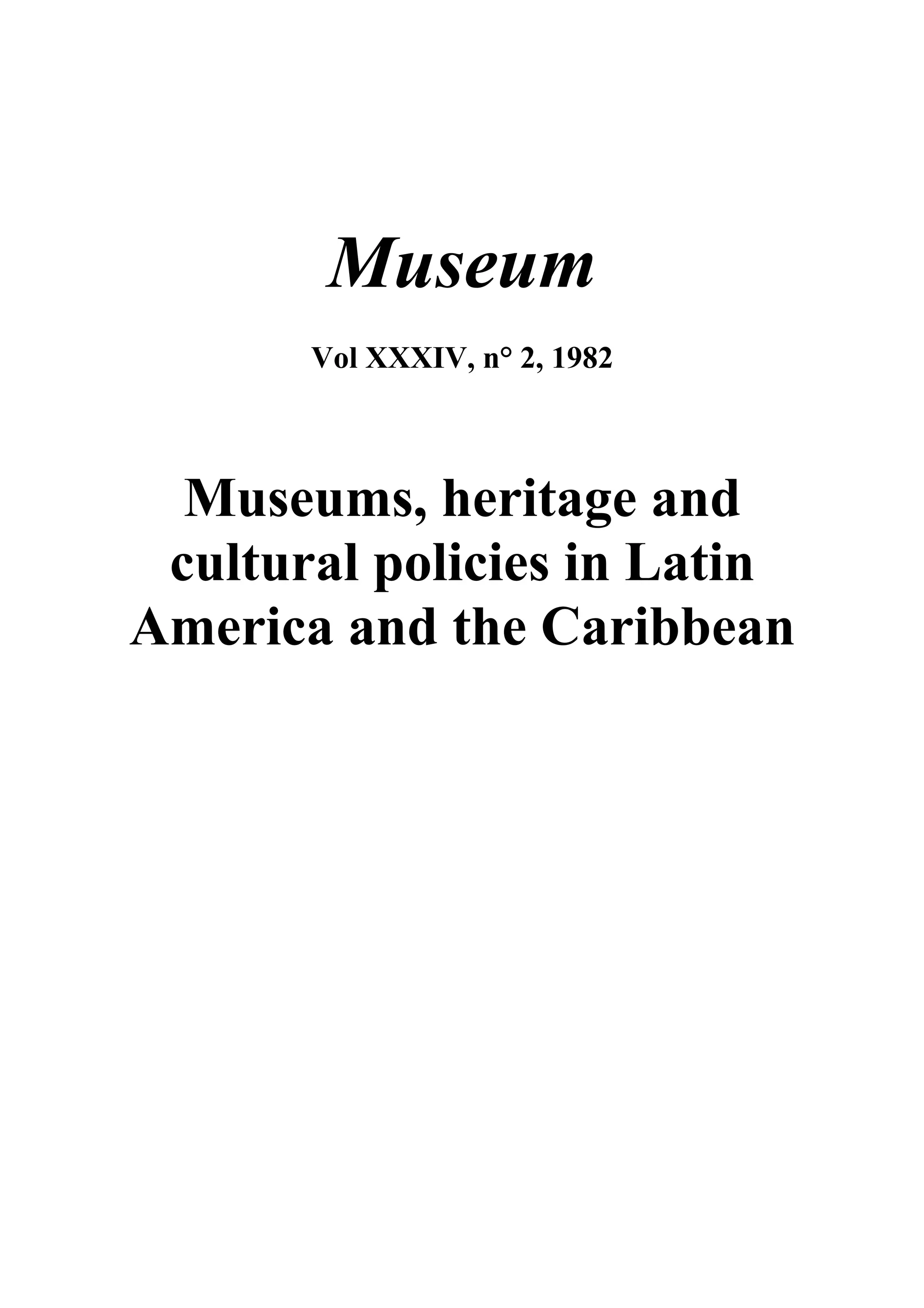

![You have also avoided corztemplating the cultural heritage azd its depositories, such

as museum, from the sole uieuIpoiizt of inaterialpreservation, but have rather regarded

thetnjrst a?zdforemost as a means of educating and enrichìng the lìues ofpeople, aizd

ds the most obuious e$wession of cultural

The purpose of this issue is twofold. On the one hand, it is intended to

provide a platform for a group of museum professionals in Latin America and

the Caribbean to share ideas and information with colleagues both within the

region and throughout the world. It has another, ‘strategic’, purpose : to bring

the significance of museum development to the attention of the policy- and

FroiztrJpiece: MUSEO ARTECOLONIAL,

DE decision-makers who will be attending the World Conference on Cultural

La Paz, Bolivia. Policies, Mexico City, 26 July-5 August 1982.

[Photo: S. de Vajay.] Our regional focus was chosen to coincide with this international event

taking place on Latin American soil. But the museum problems explored here

exist everywhere, particularly in other Third World countries where cultural

development-and, a fortiori, the role of museums in that process-still

awaits the place it deserves.

Volume XXV, No. 3 (1973), of this magazine, entitled ‘The role of

museums in today’s Latin America’, was an overview (but excluding the

Caribbean) of the situation ten years ago. It opened up new hopes for the

future. It is now time to take stock. Furthermore, our Editorial Board has been

concerned with the meagre representation in the pages of Museum of the

museum life in the region, with the obvious exception of that of Mexico.2’

This special issue-together with additional material received but which can-

not be printed here for lack of space-will certainly help fill this lacuna.

Both the thematic articles that open the issue and the monographs in the

‘Album’ section were solicited and written with the cultural policy framework

in mind. What role can and should be given to museums in our societies

today ? The concrete examples of museums that respond to a deep-rooted need

or meet it admirably, each on its own scale and specialized terrain, will, we

hope, speak with conviction to the Mexico City meeting. The notion of

cultural development launched by Unesco at the first such World Conference,

held in Venice some twelve years ago, has indeed come a long way. But

certainly not far enough. Quoting that concept, one already convinced deci-

sion-maker had this to say about museums :

1 . Amadou-hlahtar h.I’Bow, Director-General Their educational role, the opportunity for direct contact between the public and the

of Unesco, in his closing address to the products of the mind, the juxtaposition they can bring about between works of

Intergovernmental Conference on Cultural Policies

in Latin America and the Carribcan, Bogotá, different cultures, their function of preserving a fragile past, of study and of research

2 0 January 1978. on the cultural heritage from the beginning of time, their special role of organizing

2 . In a recent tally of issues published between

1970 and 1980 it was found that out of a total

the behaviour and the outlock of a society towards its own past and the past of others

of 1 9 1 0 pages printed only 156, or 8 per cent, at one particular moment, all amount to fundamental, irreplaceable aspects of a living

concerned Latin America and the Caribbean. culture. To give this up, to slacken on the effort that this involves, would be to

3 . Extract from the speech entitled ‘Museums:

Heritage and Living Culture’, given by Jacques compromise cultural development irreparably. In this sense, museums are not a sur-

Rigaud, Director-General of Radio-Télé vival or an anachronism. , . .they m e a drivìtigfot.ce behì?zd cultural dweZopmmt. Govern-

Luxembourg and former Assistant ments or societies who do not accept this idea and all it involves in terms of will-

Director-General of Unesco, at ICOM’s Twelfth

General Conference, Mexico City, 25 October- power and effort, in particular the financial implications, are condemning cultural

4 November 1980. Printed in PtoceeditzgJ of the development at more or less short term.j

Twelfth Gmeral GxfËmce md Thiytemth GetzeraL

Au&,$ o tbe Itmzatiotzal Cound o hfusezrmns,

f f

Pais, ICOM, 1981, pp. 44-5. W e hope this issue of Museum will help support that claim.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-5-320.jpg)

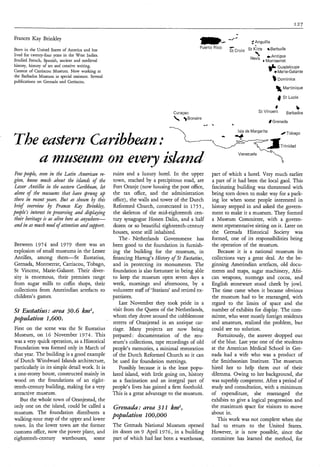

![72

Musenm dkvelobmentund

With the participation of

Marta Arjona, Frances Kay Brinkley,

Fernanda de Camargo-Moro,

Roderick C. Ebanks,

Manuel Espinoza, Felipe Lacouture,

Luis G. Lumbreras,

Aloisio Magalhaes, Grete Mostny

The article below was prepared Museum entirely on the basis o contributions

f

requested from Marta Arjona, Director of the Cultural Heritage, Cuba; Frances

Kay Brinkley, a volunteer museologist in the eGtern Caribbean; Femanda de

Camargo-Moro, Director-General of Museums, State of Rio de Janeiro; Roderick C.

Ebanh, Director of the Museums and Archaeological Division, Institute ofJamaica;

Manuel Erpinoza, Director of the National A r t Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela;Fe@e

Lacouture, Director of the National Museum o f History, Mexico City; Luis G.

Lumbreras, archaeologist and fomzer Director of the National Museum of Anthro-

pologv and Archaeology, Lima, Peru; Aloisìo Magalhaes, Secretary of State for

Culture, Brazil; and Grete Mostny, Director of the National Maseum of Natural

History, Santiago de &ìle. The various contributions were sent to the UNDP/Unesco

Regional Project for the Cultural Heritage at Limu, Peru, where Miss Juana True4

ARAWAK MUSEUM, Jamaica. A museum that

a linguist and specialist in comparative literature associated with theproject, prepared

respects the oldest indigenous population an initial synthaìs.

of the Caribbean. Stone nietate and crusher, The contributing authors have been in the forefront of the museum movement in

used by the Arawaks to crush corn. Latin America and the Caribbean; many of them are already well known to profes-

A.D. 1000 t O 1500.

[Photo; Arawak Museum.]

sional colleagues. Because of the role they play today-whether localb, regionally or

intemationd&-ìn museum curatorsh@, management and excbmge or in the formu-

lation and execution of national heritage protection policìes, Museum asked each of

these specialìsts to send us a few pages on the ‘state ofthe art’ on the Latin American

and Caribbean museum scene. In view of the forthcoming Vorld Conference on Cul-

tural Policies (Mexico Ci@ 26 July4 August 1982) we asked these authors to

eqblore the problems of mzaeums with particular reference to cultural policies in their

countries. Each replied in his or her own terms. The synthesis that follows is neither

a thorough objective survey of the situation as ir is today nor a blueprint for the

future. We hope, however, that it captures the pulse of museological l f e in the region,

whose museum face challenges that are similar to those foundthroughout the Third

TVorld

Latin America and the Caribbean make up a vast cultural mosaic of autoch-

thonous as well as European, African and, in some cases, Asian contributions.

This cross-cultural identity is still evolving, and the peoples of the region

are becoming increasingly aware of the specific values and creative potential of

their various heritages. In this process, now that they are at long last perceived

as a vital source of inspiration for development, museums are being called

upon to play a major role.

The cultural policies of the states of the region are as diverse as the cultures

themselves and the political and socio-economic systems that are found here.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-6-320.jpg)

![Museum development and cultural policy : aims, prospects and challenges 73

In spite of these differences, however, the global definition of culture proposed

by the National Institute of Culture of Panama would no doubt be welcomed

by all:

The simplest definition of culture is that it is any intentional action taken by man that

affects the world of nature. In accordance with this anthropological definition, the

concept of culture embraces all sorts of things which reflect material and spiritual

values in the historical dimension. It covers everything done by man: the experience

acquired in his labours, the mechanisms he uses for communicating his experiences so

that they may be reproduced, the methods by which he reveals their importance.

Production, technology and the relations established by people among themselves to

produce; and to distribute what has been produced-in other words, the very organ-

ization of society-are all part of culture.’

This new approach to culture is both the product and the promoter of a new

way of conceiving the role of the museum.

Ten years of euolation

1. Panama, Nation: Institute of Culture,

The round table entitled ‘The Role of Museums in Today’s Latin America’, ctLLtural i,z thr RqtLbiic of p. 18,

organized by Unesco at Santiago de Chile in 1972, marked a turning-point for Paris, Unesco, 1978.

MUSEU PARAENSE EMILIO GOELDI, Brazil.

Scientific research that includes both nature

and culture and is based on field-work is

the cornerstone of any global

socio-economic plan to fulfil the museum’s

responsibilities towards the heritage of man.

[Photo: Pedro Oswaldo Cruz.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-7-320.jpg)

![74 Museum development and cultural policy:

MUSEO IGNACIO AGWIONTE,Camaguëy,

Cuba. Exhibition hall on the presence of NACIONAL

~~USEO DE BEUAS

ARTES,

Havana.

blacks in Cuba and the slave trade. Exhibition Pwniture in Cuba.

[Photo: O Paolo Gasparini.] [Photo: Grandal, Havana.]

.. . . ... . .. .

the museology of the region. Significantly enough, that meeting was an en-

counter-no doubt one of the first of its kind-between museum people and

specialists in a variety of natural, social and applied science disciplines. Out of

this interdisciplinarity, the only adequate approach to contemporary reality,

emerged the idea of a particular social mission for the museums of the region

and the definition of the ‘integral museum’. These ideas would surely be valid

anywhere, and in the Latin American context they required as much

transformation of the institution’s role as they did entirely new ideas and

conceptions.*

Previously, museums had tended to be static institutions primarily con-

cerned with the custody and scientific classification of a heritage all too often

detached from the needs of present-day society, or-in the case of the art

museums-dedicated to the values of European art. In the last decade,

however, museums have taken on the challenge of making this heritage rel-

evant to contemporary cultural development and creativity.

The new conception naturally brought with it a new set of principles and

criteria. Ten years later, what sort of assessment can be made ? Are those ideas

still valid ? What are the iurrent preoccupations and new directions ? If so how

can we assess their implementation? What impact have they made on the

policy-makers and decision-makers ?

The first answer would be to say that the lesson of Santiago is still of

2. As neatly expressed by Mario E. Teruggi in

the issue of hlusezm devoted to the round table, fundamental relevance.

‘the Santiago round table introduced a new way In Mexico, for example, museological practice has certainly kept up with

of posing problems in connection with museums,

for a little reflection shows us that a subtle

statements of principle. Yet even Felipe Lacouture, Director of the Museo

difference has crept into the approach to museums Nacional de Historia (National Museum of History) in Mexico City, warns

as cultural institutions. Up to now a museum has that ‘museums cannot stand apart from the major national needs and prob-

only been conceived in terms of the ast, which

is its raison d’être. Museologists assemgle, lems. Because of the place of the continent in the international division of

catalogue, conserve and exhibit the works, labour, large numbers of people do not have access to the type of life enjoyed

including the throwouts, of previous cultures,

close to or far removed from our own. In the in the industrialized nations. .. . Likewise, a situation derived from the social

temporal dimension, the museum is a vector division of labour affects the culture of a large segment of the population,

which starts in the present and whose far end is

in the past. With the round table’s agreement which has no access to education and lives in the most precarious conditions.

that the museum should take on a role in We certainly cannot afford the luxury of an unstructured type of museology,

development, it is simply intended to inverse the

direction of the temporal vector which we now

one that is mere dilettantism. It must be based on a global view, in order to

get with its starting-point at some moment in integrate man into his total context.’

the past, with its far end, the “arrowhead”, Roderick C. Ebanks, Head of the Institute of Jamaica’s Museums and Ar-

reaching the present and even beyond it into the

future. In a certain sense the museologist is being chaeological Division, emphasizes the fact that ‘the implications of the con-

asked to cease merely scavenging the jetsam of cept of cultural identity are great, especially in a country like Jamaica, charac-

the past and become, in addition, an expert on

the present and forecaster of the future.’ terized by cultural pluralism based on European, African, mulatto and Asiatic

(rWusetma, Vol. XXV, No. 3 , 1973, pp. 131-2.) heritages. Out of this plurality of forms and concepts, a new nation emerged](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-8-320.jpg)

![aims, prospects and challenges 75

MusEu AO AR LIVRE,Orleans, Brazil. The

MUSEU RUA,Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. A

DA museum under construction in 1980. Local

group of photographic panels, ready to be artisans and masons from the area are

set up in different parts of the city, attract a themselves building their museum, using

new type of public and display traditional techniques. The town of Orleans

contemporary social and urban problems. can be seen in the background.

[Photo: Gabriel Carvalho.] [Photo: Museu ao Ar Livre.]

in 1762. These different heritages, often antagonistic to each other, have to be

reconciled. Thus, museums in Jamaica have the challenging role of assisting

in the fulfilment of our national motto: “Out of many, one pe~ple”.’~

Manuel Espinoza, Director of the Galería de Arte Nacional (National Art

Gallery) in Caracas, also believes that museums in developing countries are

essential in determining and strengthening the personality of the nation : ‘If

museums formerly looked to what was being done and appreciated abroad,

today their task is to promote national identity.’

Cuba, a country with only seven museums in 1959, has more than sixty

museum facilities throughout the country today. A characteristic of the Cuban

cultural policy has been the interest placed on national roots. Marta Arjona,

Director of the Cultural Heritage in Cuba, recalls the words of José Marti,

which, though written in 1891, are very applicable to today’s situation :

The history of America, starting with the Incas and up to the present, must be taught

thoroughly, even though the history of Greece is not taught. Our Greece is preferable

to the Greece which is not ours. It is more necessary to us.. . . The rest of the world

must be grafted on our republics, but our republics must constitute the trunk.

‘When analysing museums and their relation to culture,’ says Marta Arjona,

‘it is essential to bear in mind the reality of America’s history. If we want to

help rescue the cultural values of our nations by means of the museum, we

must start by rescuing historical truth. Can we study the presence of blacks in

our lands without mentioning the savagery of slavery? Can we talk of our 3 . Jamaican museology began to stir in a more

natural resources without mentioning the exploitation of the Indian, the first modern spirit during the mid-1970s. For the first

element of our identity? Can we mention our geography, the beauty of our eighty years of its existence the collections of the

Institute of Jamaica comprised Arawak and

natural resources, without pointing to the destruction brought about by in- Amerindian finds and natural history specimens.

satiable foreigners who violate it ?, The collections have expanded rapidly in the last

twenty years, and today the institute’s

Another clear example of the affirmation of national values is the Museo del Archaeological Division operates seven museums :

Hombre Panameño in Panama, which occupies, symbolically enough, what the African Museum, based on objects from the

west coast of Africa; the Arawak Museum at

used to be the terminal station of the former Panama Railroad Company. This Whitemarl, located at the site of Jamaica’s largest

American company, inaugurated in the middle of the nineteenth century, Amerindian settlement; the Fort Charles Maritime

represented a long period of economic and cultural domination by the United Museum at Port Royal ; the Military Museum ;

the National Museum of Historical Archaeology,

States in the Isthmus. Today the museum exhibits an extraordinary collection which includes an explanation of the

of objects testifying to a national culture synthesized through centuries of archaeological process ; Old King’s House

Archaeological Museum (which was the

cohabitation among at least a dozen ethnic groups. In its different didactic governor’s residence up to 1S72) ; the Peoples’

exhibits-Synthesis of Panamanian Culture, Archaeology, Gold, Culture Con- Museum of Craft and Technology, based on a

collection of indigenous crafts and industrial

tact and Ethnography-a material summary of the past and present of Pana- elements used and created in Jamaica over the

manian man is displayed. past 300 years.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-9-320.jpg)

![aims, prospects and challenges 77

ation ; often the higher-echelon museum staff, apart from doing research, also

teach at a university. Many museums publish their own scientific reviews. Dr

Grete Mostny remarks, however, that ‘we need to establish a pedagogy suited

to the museum-still lacking in Chile-in order to develop a strategy for the

communication of knowledge’. Nevertheless, a number of experiments

launched by museums, such as the ‘Juventudes Científicas de Chile’ (Science

for the Youth of Chile) and their ‘Ferias Científicas Juveniles’ (Young Peoples’

Scientific Fairs) have become an important national movement and receive the

support of the National Committee for Scientific and Technological Research

(CONICYT) and the Academy of Sciences of the Instituto de Chile.

In Jamaica, museologists planning exhibitions that tie the different heritages

into the others and try to reveal as much as possible of the continental histor-

ies are careful to prepare didactic exhibits that take into account the fact that

60 per cent of the population is illiterate. In order to make this information

accessible, museum attendants have been trained to carry out guided tours. In

addition, a three-dimensional exhibition script format is being developed,

starting at a basic literate level and going up to a high-school fifth-form level.

At this stage, in the light of such hopes, the critical observer will be justified

in asking how well practice has corresponded to theory or, to put it more

bluntly, to what extent the means available have been adequate to the ambi-

tions expressed. Museums in Latin America and the Caribbean-with the

possible exception of one or two of the most prosperous countries-share the

scarcity of financial resources and the relatively low priority in the hierarchy of

state-supported services that are the lot of museums throughout the develop-

ing world. At an informal consultation on the ‘state of the art’ with respect

to the preservation and presentation of the cultural heritage, organized by

Unesco in Paris in June 1981, it was pointed out that many countries lack a

‘clear national policy for the protection of the cultural heritage, defined opera-

tionally as part of the overall development planning process. The problem is

both one of decision-making and of a society-wide approach. At government

t FORTCHARLES MARITIME MUSEUM, Royal,

Port

Jamaica. A museum devoted to maritime

history and technology in the region,

created in 1978 and installed in Nelson’s

House.

[Photo; Fort Charles Maritime Museum.]

Latin America’s rich architectural heritage is

given a new life as museums are created in

historic buildings. The courtyard of the

Palacio de la Real Audiencia, a neoclassical

building dating from 1804, the former seat

of the supreme colonial authority, which

is being restored to its original character

and will house the Museo Histórico

Nacional de Chile.

[Photo; Museo Histórico Nacional de Chile.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-11-320.jpg)

![78 Museum development and cultural policy: .

CHILENO ARTE

MUSEO DE PRECOLOMBINO,

Santiago de Chile. Conservation and

laboratory infrastructure is still lacking in

many institutions. This museum,

inaugurated in December 1981, has a

well-equipped textile conservation and

restoration workshop.

[Photo: Museo Chileno de Arte

Precolombino.]

level, as at the level of the general public, preservation and presentation of the

heritage are viewed as something apart from life and culture today.’

Among the specific points noted were the following :

7 . Afo~semzhopes nevertheless that the material

presented here will prove to be sufficiently Insufficient protective legislation, which is the basic instrument of decision-

thought-provoking to justify some frank making.

self-evaluation that might be published in a

future issue. Personnel and human resources-the instrument of implementation-to pro-

8. Eduardo Martinez, La politira culturd in tect cultural property are not adequately provided by states, even when the

Mé.-ico, pp. 67-8, Paris, Unesco, 1977.

9 . Solana explained that ‘in keeping with the latter adopt legislation that indicates the necessity of such infrastructure.

first of these principles, the government considers The necessity to clarify the processes of policy-making in relation to the cul-

museums above all as attestations of freedom of tural heritage. Who are the policy-makers ? What expertise is required for

creativity and cultural expression. Al museums,

l

each according to its character and p-irpose, must policy-making? How can the policy-makers be influenced ?

testify to the unrestricted development of culture, Shortcomings in the way the region’s museum professionals themselves have

be it at the international, national, or local level.

They must not hamper spontaneity and genuine attempted to overcome these obstacles to this situation have been implied in

art, scientific discovery or historical facts with the observations cited above. Too implicitly perhaps, and some readers may

tempomy official interpretations. Museums are by

nature generous, hospitable and essentially find the self-assessment, together with the comments formulated in other

anti-doctrinarian institutions. articles, somewhat lacking in critical force.’

‘The increase and improvement of our Be that as it may, and in defence of museum workers themselves, it cannot

museums are evidence of the support and

stimulus that the Mexican Government, by virtue be denied that many governments of the region have not yet realized the place

of the second principle mentioned, is givirig to of museums in the success of their cultural policy. There are noteworthy

cultural creativity.

‘The state’s intervention in ensuring the exceptions. In Mexico and Venezuela, for example, museums are an integral

accessibility, dissemination and distribution of part of a programme clearly stated in national development plans. Thus

cultural properties-the third principle-applies

especially to museums. The government considers Mexico’s National Plan for 1977-82 states :

them to be an integral part of education and it

intends to convert them into dynamic With a view to promoting a better knowledge of the nation’s history and of the

instruments of a truly democratic education. In archaeological and ethnographical characteristics of the population, the National Plan

particular, it is encouraging teachers to use foresees, among other things, the establishment of a National Organization of

museums as an educational resource and to

introduce their pupils to the habit of visiting and Museums. Existing museums in both small and large towns would be linked to it. As

enjoying them. a result, the inhabitants of the country will be able to have a view as complete as

‘Finally, museums are an invaluable help in

preserving the national cultural heritage, the

possible of the historical and cultural heritage of the nation and of the world. This will

fourth of the principles guiding Mexican cultural be done in a programmed manner. An endeavour will also be made to initiate students

policy. This last point is particularly relevant in in the study of museography, at different educational levels, by organizing small

view of the title theme of this conference: “The

World’s Heritage-the Museum’s museums in each school, where objects of a purely local or even personal significance

Responsibilities”. could be shown?

‘Every country must preserve and disseminate

the cultural properties that constitute the Delivering the inaugural address at ICOM’s Twelfth General Conference in

particular characteristics of its peoples. Artefacts Mexico City, Fernando Solana, Mexico’s Minister of Public Education, made

produced by man last longer than he does and

have the virtue of evoking the human realities it clear that the four principles underlying his government’s cultural policy-

that gave rise to present forms of cultural ‘freedom for creation, encouragement of cultural production, participation in

expression. Governments have a duty to preserve

the cultural heritage of their countries and to the distribution of cultural properties and services and preservation of the

stimulate the creativity of their peoples. nation’s cultural heritage’-also applied to the development of museum^.^

This duty goes hand in hand with the obligation

to strengthen sovereignty and national

‘Venezuela’, says Manuel Espinoza, ‘constitutes a unique case in the context

independence.’ of Latin America. Its democratic experience has generated a level of conscious-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-12-320.jpg)

![aims, prospects and challenges 81

Before starting, the group made a general inventory of the specific heritage

of the material culture of the islanders which needed to be preserved and of

which the latter should be made aware. The group had to decide what the

collections would contain and on what basis the museum would function.

They also considered whether to ask th: government for aid or not.

Since Carriacou has three cultural heritages-African, Amerindian and

European-the museum was planned with a section for each culture. ‘As to

funding,’ observes Frances Kay Brinkley, ‘considering the political situation at

that time, it was decided not to ask for the government’s help. The main

source of funds would be membership dues. These came from Regular and

Associate Members and Patrons. A Special Associate Membership was estab-

lished, open only to Carriacouans living on the island. W e did not want

anyone saying he was not a member because he could not afford the fee. The

minimum due was set at 1 EC a year (2.70 EC = $1).’

Another important decision was what to include in the museum’s collec-

tion. The criteria were the amount of space available, achieving a balance of

collections and securing public interest : ‘The first two are obvious restrictions

for all museums. The third took a form that is perhaps something that would

not occur to a European museologist. If you .have succeeded in giving people

an affection for and a pride in their museum, they are going to start bringing

you things they have at home. Naturally, sometimes there will be things you

will have to refuse. But it is better to take them and store them (if they are

not welcome, or are absolute horrors) than damping the enthusiasm for the

museum born in the donor’s heart.’

But in the final analysis and despite such success stories, museums must

continue to rely heavily on state support. Roderick C. Ebanks reminds us aptly

that ‘the task of museum development in Third World countries passing

through an economic crisis is a very real challenge. But the lack of financing

is not the major factor in the lack of development. Rather lack of knowledge,

of trained people, of clearly defined objectives, of advanced planning and of

integrated cultural services all play havoc with the best intentions.’

The solution proposed by this museum expert is, in the first place, to

motivate professionally the museum staff and to educate the public. Among

the latter are the politicians and administrators of cultural affairs, who ‘are not

informed about museums and their demands: they think about museums as

storehouses for national exotica, or as a way of enticing a few more dollars

from the tourist’s pocket. Consequently, they are not encouraged to invest

funds in a museum. W e must make these senior decision-makers and policy-

makers aware of the museological process.’

BANCO CONTINENTAL,Lima. Children and

museums.

[Photo: s. Mutal.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-15-320.jpg)

![82

MUSEO HOhlBRE PANAhfEÑO, Panama.

DEL

Interpreting the history of the region’s

material culture.

[Photo; Sylvio hhtal.]

MUSEO ARQUEOLOGICO Y GALERIASARTE

DE

DEL BANCO CENTRAL DEL ECUADOR, Quito.

Christ being baptized by John the Baptist.

[Photo: S. Mutal.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-16-320.jpg)

![Thus the Central Bank of Ecuador has Belén Rojas Guardia

acquired archaeological, ethnographic and

numismatic collections as well as colonial

and modern art. Thousands of objects are

now made accessible to Ecuador’s people

A fair share in Venezuela

through the bank‘s museums in Quito,

the capital, and in the cities of Guayaquil,

Cuenca and Manta, as well as its galleries

in Esmeraldas, Ambato, Latacunga, Rio-

bamba and Loja.

In addition to the budget it earmarks How museums obtain sufficient financial museums, justifying their claim to be al-

for the running of its museums, the bank resources; whether from state budgetary located resources as befits their role.

also donates funds each year exclusively allocations or through contributions The success achieved by the gallery in

for carrying out projects of archaeological from the private sector, will depend on a its first year, the formation of a team of

and anthropological research and the series of factors and circumstances. These professionals whose will and dedication

safeguard of monuments. Funds amount- include the priorities established for the were revealed by putting theory into

ing to as much as 3 5 million sucres a year cultural sector in any particular develop- effective practice (eighteen itinerant exhi-

(about a million dollars) are also ear- ment model, as expressed in a country’s bitions that travelled all over the coun-

marked to set up museums and present national plans, and the museum try ; research, conservation and preserva-

exhibitions throughout the country. authorities’ skill in implementing a bold tion) allowed it to obtain the targeted

This example could usefully be fol- and innovative fund-raising strategy. budget that year. This sum was approxi-

lowed by similar establishments in other The institution’s efficiency, dynamism mately equivalent to the budget for the

countries. Already the Banco de la Re- and scope are obviously decisive elements previous ten years combined. It did no

pública of Colombia is carrying out a of museum financing. The quality of its more than meet a need that had long

similar task, with the Museo del Oro and exhibits, its degree of responsibility and been ignored.

its archaeological research programmes. professionalism, its training and educa- This unprecedented measure gave rise

If the museums of Latin America and tional activity, its capacity to attract every to controversy about the rights of decen-

the Caribbean could rely on the under- kind of public-in short, any action that tralized cultural institutions to go directly

standing of those who govern them and confirms its historical role in shaping an to the legislature for their budgets. The

therefore on sufficient funds, they could authentic cultural identity-will be a debate was resolved in our favour, and

well become the most efficient vehicles positive asset. Venezuela has a demo- the country’s museums were given the

for promoting and disseminating culture, cratic, pluralist and participatory political go-ahead to implement projects vital to

by delivering valid messages and render- system, and an economy now grounded the country’s cultural personality, enab-

ing real service to our countries, helping in oil wealth, all the basic industries of ling them to consolidate their situation.

our people to overcome the bitter reality which are managed by the state. The In 1980 2 1 per cent of the total alloca-

of so many political, social, economic and latter assumes a clear responsibility to tions of the National Cultural Council

cultural problems. Effective museum ac- promote and encourage other sectors was set aside for the museum sector.

tivity will be the key that unlocks the (non-productive in the strict economic The museum’s active and dynamic

door to better days for the nations of sense) that form part of an overall de- presence in our society has generated a

Juárez, Bolívar and San Martin. velopment model, the final aim of which climate of confidence. New avenues of

is to stimulate the capacity for innovation financing are being opened up. These in-

[Transhted from Spanish] of individuals and communities in a har- clude the private sector, which is becom-

monious relationship with the environ- ing increasingly aware of the need to

ment. participate in and contribute to the de-

The state is the greatest, and almost velopment of an institution that belongs

exclusive, financial source of a large pro- and caters to everyone.

portion of the country’s cultural institu-

tions (whether they are governmentally [Tradated fi’oflz Spanish]

administered or not). In 1977 the new

National Art Gallery (see the article

p. 105) first took the initiative of directly

and independently presenting its draft

budget separate from the general budget

traditionally submitted to the National

Cultural Council (CONAC) . Logisti-

cally, this move attracted the attention of

organizations concerned with budgetary

decision-making at the highest level to

the problems facing the country’s

museums. It also temporarily separated

the gallery from CONAC by a ‘strategic’

action that was perfectly legal yet imagin-

ative enough to dramatize the state of our](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-19-320.jpg)

![86

de una ciudad

nes la habitan.

MUSEO SANTIAGO,

DE Santiago de Chile.

Tracing the history of the urban

community: model of the former residence

of the Count of the Conquest.

[Photo: Museo de Santiago.]

N w directions

Fernanda de Camargo-Moro in mnsenm orgmizutìon

B.A. and postgraduate degree in museology, M.A. It is certainly an enomous responsibility t o colonial times, which bequeathed to us

and Ph.D. in archaeology. Assistant Professor and discuss mzueum Organization in Latin Am- the essential medium of communication

subsequently holder of the Chair of Archaeology

in the Faculty of Museology of the Museu do

erica and the Caribbean in oize short article. of cognate languages, are still powerful

Homen, Rio de Janeiro, 1968-71. Associate Femanda de Camargo-Moro,who hm consid- factors of cohesion.

Professor of Anthropology at the Pontificia erabIeprofessìoolaal experience in her own roun- Our efforts are greatly inhibited,

Universidade Catolica of Rio de Janeiro, 1974. try, Brazil, and more than passing acquain- however, by the difficulties of inter-

Director of Cepi (Iconographic Research Centre), tance with variousprogrammes in otherparts national travel within the region. In most

1972-73, and Mouseion (Centre of ,Museological

Studies and Sciences of Man) from 1973. of the continent, stresses that the views she cases, we are dependent on the air services

Director of AMICOM-Mouseion seminars, Real expresses below are high4 personal and still linking capital to capital, which are usu-

Càbinete Portugues de Leitura, 1973-79. evolvìng, a is the entire process of museology ally very costly. Distances are enormous.

Supervisor of Museology at the Museum of in the region. Rio de Janeiro, for instance, is closer to

Images of the Unconscious from 1973. President

of the Rio de Janeiro Museums Foundation, Lisbon than to Mexico City. Overland

1979-80. At present Director-General of travel is easier on the Atlantic side, but

Museums in the State of Rio de Janeiro Volume XXV, No. 3 , of Museum, en- the problem of distance is compounded

(FUNARJ), President of the Council for the titled ‘The Role of Museums in Today’s by the curvature of the Brazilian coast

Protection of the Cultural Heritage of the City of

Latin America’, appeared too soon after and the indented coastline of the

Rio de Janeiro, Chief Curator of the

E. Klabin Rappaport Collection, Director of the the Santiago round table of 1972 to re- southern. zone. Transcontinental overland

ICOM-Brazil Museological Documentation flect the radically new approach the routes from the Atlantic to the Pacific are

Centre, President of the Brazilian Committee of museums in the region were to adopt in rare and in all cases time-consuming. And

ICOM and Member of the Executive Council of response to the ideas developed during sea travel, even via the Panama Canal,

ICOM 1981-83. Author of books and articles on

museology, archaeology and preservation.

that meeting. which is still in use, is extremely circu-

Has carried out several museological consultant The changes have taken time to ma- itous.

missions for Unesco. terialize. The geographical configuration These difficulties, combined with the

of Latin America, with the slender strip world economic crisis, have tended to

of Central America joining Mexico to hold up the spread and implementation

South America and the long expanse of of the new museological ideas. But now

the latter broken up by the barriers of the that ten years have elapsed, we can begin

1. Jamaica has embarked on a vigorous *

museum organization programme and is forging

Andes, the Amazon basin and the Pan- to take stock of the changes in Latin

strong l i n k with the African museum movement. tanal, restricts the scope for effective im- America and consider the extent to which

The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago has already plementation of joint programmes. On the new approach has also had an in-

implemented an extensive museum renovation

and expansion programme initiated in 1976 with the other hand, our common heritage fluence in the Caribbean and created

Unesco’s support. and the pervasive Iberian influence since linkages with the continent.’](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-20-320.jpg)

![New directions in museum organization 87

Most of our museums were established by the community in their activities. This

in the nineteenth century in the image of was the key to survival.

European museums, generally those of The redefinition of the museum con-

the country wielding the greatest in- cept called for at Santiago implied a con-

fluence in the region at the time. comitant redefinition of our heritage and

Although the collections, generally trans- hence a change in the mentality of the

’

ferred and donated by ruling or govern- cultural élites of our countries, in many

ing families2 or assembled as a result of cases still steeped in the Europeanizing

scientific and artistic missions from concepts of the nineteenth century. In

Europe, were of a very high standard, the order to disseminate the new ideas, it was

underlying conception of the museums decided to set up a Latin American Asso-

was extremely partial. The collection and ciation of Museology (ALAM). The asso-

presermtion of local objects were entirely ciation was established at the beginning

neglected ; many of these objects were ex- of 1973 at an intensive and lively meet-

ported. and the remainder were displayed ing in Quito, but despite the enthusiasm

in the light of a foreign interpretation. of some of its members it never really got

There was no documentation of either off the ground. In the meanwhile, the

imported or exported collections. Local seeds of the new philosophy of muse-

material was ordered according to con- ums had found fertile soil and the first

ceptions that led inevitably to its identifi- fruits were beginning to appear.3

cation as natural history collections : the The creation of the National Museum

indigenous peoples and their cultures of Anthropology in Mexico City in 1964

were shown side by side with exotic flow- is considered by some as a turning-point MUSEU ” m o REINADE, de Janeiro.

P Rio

ers and animals. A further anomaly was in the museological movement in Latin Reaching out to the disabled: a deaf-mute

the exclusion of the cultures of Asia, Af- America. In our opinion, however, it was child being taught rhythm.

[Photo: O Edson Meirelles.]

rica and our own continent from the merely an isolated event whose implica-

rather insipid fine arts museums or their tions were more museographical than

discriminatory classification in terms of philosophical. Far be it from us to belittle

ethnography rather than art. the extraordinary achievement that the

Up to the end of the 1960s modern- Mexican museum represents or to ques-

ization work on our museums served. tion its undeniable beauty. It altered

purely decorative purposes. Changes were many preconceived ideas in the region.

made only in items of equipment, for in- Museums were no longer seen as musty

stance display cases and coloured panels. storehouses of crumbling relics rather ,

Although the essential link between than living memories, but became instead

museums and education was recognized, political instruments, sources of prestige

very little was done to turn this fact to and monuments to our indigenous ances-

account. Only a limited amount of re- tors, affording greater objectivity and

search was conducted, with no attempt at clarity of definition in the archaeological

interdisciplinarity. The notion of conser- rather than the ethnographical field. But

vation was non-existent, the only work for a better understanding of contempor-

carried out under this heading consisting ary Mexican culture as a whole, we must

of the restoration of paintings. Between turn to the magnificent Museo Nacional

1950 and 1960 the number of mu- de Historia in Chapultepec Castle.

seumsnational, state, municipal, pri- The National Museum of Anthro-

vate, encyclopylic and monographic pology, while attaining a very high stan- 2. For example, the Etruscan collections

-increased sybstantially, without basic dard of display, tends to lay undue em- brought over by Tereza Cristina, Empress of

organization /or structural conception. phasis on the monumental in an aesthetic Brazil, which are now in a natural history

museum, the National Museum of Rio de

i

They were ‘bsolete from the outset and context, and it does not enter into a dia- Janeiro.

devoid of ny prospect of development. logue with the population, least of all 3 . As evidence of the impact of the new ideas

Static in CO cept, designed primarily with with communities in the most deprived in various parts of the region, we may note, in

the first instance, the plans for the Archaeological

a view to el borate inaugural ceremonies, areas.4 Museum and Art Gallery of the Central Bank of

they rapidly ‘degenerated into a formless Ecuador, El Salvador’s Houses of Culture and

travelling exhibitions (1974), Brazil‘s proposals

conglomeratio’n of bric-à-brac. At the be- Towurds ‘museum on u for community ecomuseums and the Museum of

ginning of the 1970s, when all sectors Images of the Unconscious (1973-74), the

were faced with financial difficulties, the

humazz scule’ programmes of the Museum of Natural History

of Santiago de Chile (1973-74), the Casa del

museums, already struggling to make The idea of a museum on a more human Museo in Mexico (1973-74) and the

ends meet, were particularly hard hit. It scale that evolved in 1972 did not restructuring of museums launched by Trinidad

and Tobago in 1976.

was clear that they were not accomplish- succeed in preventing all the capitals of 4. This aim was to be fulfilled by the Casa del

ing their crucial mission of preserving the Latin America and its neighbours from Museo, a project brought about by the new ideas

cultural heritage ; something was miss- slavishly copying the famous Mexican which have permeated all of its programmes.

Mexico is also pursuing a successful policy of

ing-a firmer bond uniting them with museum without the slightest attempt at dialogue with the population through smaller

the population and stronger participation adaptation to national realities. Even to- museums.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-21-320.jpg)

![88 Fernanda de Camargo-Moro

MUSEO AMANO,Lima. Attaining and

preserving technical standards : a small,

privately owned museum of pre-Columbian

textiles.

[Photo: Museo Amano.]

A sustained concern to preserve both the

cultural and natural environment is

emerging : extramural activity to promote

understanding of agriculture carried out by

museums in the Rio de Janeiro network.

[Photo; SMU-FUNARJ.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-22-320.jpg)

![N w directions in museum

e organization 89

day it is quite common for the techno- the foundations of a modern and dynamic a recent programme and is already yield-

crats of our countries to return from a museology by inaugurating the Archaeo- ing favourable results. For technical sup-

visit to Mexico City utterly obsessed with logical Museum and Art Galleries of the port, it relies on the ICOM-Brazil

the idea of copying the National Museum Central Bank at the beginning of the Museological Documentation Centre.

of Anthropology, forgetting that each 1970s, a project commensurate with the An activity of major importance in the

country has its own scale of collections, human realities and aspirations in our re- region, which exerts a direct influence on

historical background and aspirations, gion. In addition to the Quito museum museum organization in Latin America,

and that its museums must take all these and gallery, the programme also provided is the UNDP-Unesco Regional Project

elements into account. It is by no means for decentralization through the estab- for the Cultural Heritage. This project,

easy to persuade these technocrats, trus- lishment of new museums in other parts which has its headquarters in Lima, has

tees and financial authorities to take an of the country, the organization of ar- been the motive force behind a series of

interest in simpler activities on a smaller chaeological missions and the develop- activities in the region. As well as

scale, just as it is not easy to secure sup- ment of research. promoting the organization of new

port for the preservation of museums and In Brazil an example of the extensive museums by offering encouragement and

their collections. It is and always will be form of organization is the system of technical support, it also helps to restruc-

easier in many parts of the world to ob- museums that is gradually being estab- ture old museums and has initiated in-

tain financing for costly prestige projects lished in the state of Rio de Janeiro by valuable training activities. (See article

of colossal dimensions than to meet the the General Directorate of Museums at- below, p. 94.)

more modest cost of viable projects con- tached to the Arts Foundation of the The seeds of a new museology have

ceived in human proportions. state. This Directorate, which is the suc- been sown and have already begun to

Nevertheless, the idea of a museum cessor to the State Museum Foundation, bear fruit, although a full harvest is yet to

tailored to community needs is gaining a body formerly responsible for a group of come. Our museums have shed their

'

ground and is gradually becoming a museums operating in airtight compart- gaolhouse image and are gradually assum-

characteristic feature of the region. De- ments completely divorced from the popu- ing the aspect of the agoras of ancient

spite all difficulties of communication and lation, is at present engaged in con- times.

exchange, the reaction has spread structing an integrated system, based

through the collective unconscious of the on two major criteria: conservation and [Tranrlatedfrom Portuguese]

region. A sustained concern to preserve dynamic development. In the field of

both the cultural and natural environ- conservation, the Museology Department

ment is also emerging. of the General Directorate lays down

Museum collections are now being technical standards governing inventory,

studied from a multidisciplinary point of conservation and maintenance in respect

view. Objects used in daily life are seen to of museums and their collections, con-

be worthy of preservation. Small trols the research and museographical

museums tracing the origins of urban and planning activities of the twelve mu-

rural communities have been set up, and seums or houses of culture and organizes

the principle of decentralization of collec- an extensive programme of temporary ex-

tions has begun to be observed. The prac- hibitions that travel to all parts of the

tice of despoiling a community of collec- state. In the field of dynamic develop-

tions providing information about its ment, the educational action programme

background and origins has been aban- acts as a stimulus to the programmes of

doned. Collections are increasingly in the twelve museological units, draws

keeping with the specific character of the their attention to municipalities that are

museum and the interests of the local still without museums and promotes in-

community. tegration of the programme with the

A crucial development was the elabor- local community. The programme is

ation of non-formal educational pro- headed by the Primeiro Reinade Museum

grammes, within which museums began in Rio de Janeiro, which carries out pilot

to be used as three-dimensionalinforma- projects and analyses their results for the

tion systems. A new spirit of creativity is benefit of the system. The impact of the

abroad, with inventiveness taking the programme is gradually being felt at all

place of luxury and grandeur in each new levels of society, in both urban and rural

museographical project. areas, thus forging links between the

An excellent case in point is Ecuador's museum and the various local com-

recently developed museological project, munities.

which is extensive in conception but Another series of extremely important

closely linked to the aspirations of the extensive projects based on community

population. Systematic studies in the field integration is being implemented by the

of anthropology have confirmed that the interesting Museu do Homem do Nord-

country's cultural history dates back 'at este in Recife (Pernambuco), the Dom

least 12,000 years, a conclusion that is Diogo de Souza Museum in the southern

borne out by very rich archaeological ma- part of the country and the State

terial. The Central Bank of Ecuador laid Museums Division in São Paulo. This is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-23-320.jpg)

![pects o staff training

f

Felipe Lacouture

The Republic of Argentina has played a als could be classified into five categories

Born in Mexico in 1928. Studied architecture at pioneering role in the provision of sys- ranging from Grades A to E, and on the

the ,UniversidadNacional Autónoma of Mexico,

1947-52 ; also read archaeology and art history. tematic training for museum staff since assumption that each category after

École du Louvre, 1952-53. Taught architecture 1922, when a course to train experts in Grade B was capable of passing on to the

at the Universidad Iberoamericana at UNAM museum work was established in the next grade. In this way, through constant

1956-59. Lectured in aesthetics at post-secondary Faculty of Arts of the National Univer- practical experience and a certain amount

level, 1965-68. Professor in museology at the

Latin American Institute for the Conservation of

sity of Buenos Aires. This course con- of necessary additional study, the

Cultural Property, Mexico City, 1971-77. tinued to be given for thirty-seven years, museum worker may hope to become

Director of the Museo de Arte e Historia at and subsequently other institutions were better qualified and so obtain promotion

Ciudad Juarez, 1964-70. Head of the created for the same purpose, so that on the professional grading scale.

Department of Regional Museums, INAH, there are now in all four such institutions

197,0-73. Director of the Museo de San Carlos,

1973-77, and Head of the Department of in existence, offering seven different Two approaches to staf

Graphic Arts of the Instituto Nacional de Bellas courses of museology at various levels.

traìnìng

Artes, 1974-77. Director of the Museo Nacional Although efforts have been made in

de Historia, Mexico City, since 1977. Has many Latin American countries, or are What results are obtained by the Argen-

practised as an architect-restorer, has carried out now being made, to provide training on tinian and Mexican approaches, or sys-

mrious missions for Unesco and the OAS and has

attended numerous international meetings of a systematic basis, as in Argentina, there tems, in the context of staff training?

specialists. have also been attempts to set up on- Each gives rise to its own problems, in-

the-job training schemes, which are large- cluding that produced by the liberal ap-

ly autonomous. This is the case in Mex- proach of establishing a school and taking

ico, which took its first steps in the field on students who have no guarantee of

of museographical presentation in 1934 , work when they have finished their

establishing many of the features that are studies.

still characteristic of museum work in In Argentina the School of Museology

Mexico today with the foundation of the started giving courses for school-leavers

Museo Nacional de Artes Plásticas, in in 195 1. There are two courses, the first

which such outstanding artists as Julio to train museum auxiliary staff, which

Castellanos were involved and which, it lasts two years, and the second for a de-

might be added in passing, marked the gree in museology, which lasts an addi-

beginning of the ‘decorativîst’ bias in tional two years.

Mexican artistic activity. I should also The Higher Institute for Technical

like to mention the efforts made by the Training and Education in Museology

Instituto Nacional de Antropología e also trains people who have completed

Historia (INAH) to retain the emphasis their secondary studies to become

on the educational function of museum museum assistants or museologists, and

A photography theory class at the School exhibitions, which is so necessary for a offers an interesting one-year course for

of Conservation, Restoration and Museology public not familiar with the subject- qualified teachers that enables them to

at the National Centre of the same name, matter of anthropology. qualify as museum educators. In Latin

Bogotá, 1980.

[Photo: Colcultura.] However, these two tendencies within America, as elsewhere, a problem has al-

museography, which came to represent ways been posed by schoolteachers who,

real extremes, were finally fused in 1964 for all their knowledge, do not know

as a result of the work of a team of an- how to make appropriate and worthwhile

thropologists and architects led by a gen- use of museums in their teaching. (In

eral co-ordinator trained in history, art Mexico attempts have been made to solve

and architecture as well as anthropology. this problem by individual museums that

Many of the features that formed the have taken the initiative of providing

basis for the development of Mexican special courses for teachers so that they

museography thus evolved not in an aca- will learn about the museums themselves

demic context but in a strictly practical and thus be able to pass on the know-

way. ledge to their students.)

Later the need was felt for a hierarchi- In 1972 the Escuela Superior de Con-

cal structure and systematic organization, servación de Museos (Higher School for

and a grading commission was therefore Museum Conservation) under the aus-

set up within INAH so that different pices of the Argentinian Institute of

levels could be established for members of Museology established a three-year course

staff according to their knowledge and to provide technical and professional

experience. A series of definitions was training for those who have obtained

drawn up so that all museum profession- their secondary school-leaving certificate.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-24-320.jpg)

![Aspects of staff training 91

Practical work on mural-painting restoration

in the Templo de Santa Clara, Bogotá, as

part of the course on restoration of movable

cultural property.

[Photo; Colcultura.]

. __

Mention should also be made of the

National Course of Museology, which

comes under the National Commission

z f

for Museums, Monuments and Historical

Sites, which provides courses lasting three

years at the post-secondary-school level to

train specialists for historical museums.

For a period, a somewhat similar kind of

training was provided by the Universidad

de Luján, but the course was sub-

sequently abolished.

In Mexico, the training programme

organized since 1968 by INAH’s

National School of Restoration in Chu-

rubusco to train graduates in restoration

work includes a systematic introductory

course of museology, considered essential

in view of the fact that professionals of

this type are mainly required to look after

the collections belonging to the INAH

museums.

Later on, in 1971, Mexico realized the

need to provide intensive courses, in view

of the increasing importance of museums students were just as likely to be sent

in the country and the urgent need to to the school as Argentinian museolo-

train personnel for them. This situation gists. It therefore became necessary to

coincided with the creation of a course of provide preparatory courses and at the

museographical training as a result of an same time to determine an appropriate

agreement with the Organization of stage or level of instruction, which could

American States (OAS). It was decided only be decided upon when the students’

that the course would last nine months, educational background was known.

offer one OAS fellowship for each As part of a generally liberal policy,

member country of the organization and which was not specifically directed

be held in the INAH School of Restor- towards the personnel of institutions,

ation. It was given for nine consecutive there was established in Mexico in 1979

years and trained a total of 2 5 5 people, of a master’s degree in museology within

whom approximately 40 were Mexican.’ the above-mentioned Churubusco school,

The course was divided into three which had by that time been renamed the

levels : a theoretical level approaching the School of Restoration and Museography.

study of museums through the social On the one hand, it was decided, in gen-

sciences, psychology, cultural anthro- eral terms, to adopt an integrated ap-

pology and pedagogy ; a second level cov- proach to the various techniques of

ering the organization of museum work, museum work, starting with the subjects

ranging from research and documenta- of collection, research, documentation,

tion to education and cultural activities, conservation and restoration, before go-

with emphasis on display techniques ; and ing on to display techniques, the use of

a third level where the student was free, explanatory material, education and the

on the basis of his own subject interests, diffusion of information and, finally, mar-

to choose a particular kind of practical ket research techniques designed to im-

work, which was then carried out in one prove communicationwith the museum’s

of the various national museums. public. On the other hand, attention was

However, this plan, which appeared so also given to the whole range of know-

well organized, encountered serious prob- ledge that can be presented in a museum,

lems in practice, as Churubusco was never including cosmology, geology, biology,

able to intervene directly in the selection ecology, palaeontology, palaeoanthro-

of students, who were mostly chosen by pology, archaeology, cultural anthro-

1. Unfortunately this course has now been

the OAS member states themselves, P0logy7 ethnography, history, temporarily suspended owing to administrative

with the result that secondary-school and art. All this clearly demonstrates the problems.-Ed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-25-320.jpg)

![92 Felipe Lacouture

Working group during an interdisciplinary

retraining seminar carried out by the

SMU-FUNARJ in Rio de Janeiro.

[Photo: 0 Edson Meirelles.]

’Mexican desire to create an integrated ap-

proach to museology in which culture is

seen as a structured whole.

According to this approach, a museum

professional is regarded as a generalist

who co-ordinates a series of techniques

and sciences in order to carry out

museum work successfully. The master’s

degree was therefore organized so as to

give graduates in various subjects training

in museum work at the postgraduate

level. Up to the present time, two com-

plete courses have so far been given and a

third is about to begin.

Truinìng initiutiues elsewhere

The training courses organized in Bogotá

by the UNDP/Unesco Regional Project

for the Cultural Heritage in co-operation

with Colcultura are described separately

(see p. 94) ; suffice it to explain here

that the aim of the course for adminis-

trators was to provide them with the

necessary basic knowledge to develop in countries where all areas of life and knowledge of those basic techniques that

training courses within their own institu- work are influenced by liberal ideals. The are so essential in restoration and conser-

tions and thus, as fir as possible, create a situation in Ecuador is of great interest. vation work and that moreover provide

multiplier effect. The situation is so The School of Restoration, Antiquities basic knowledge about the intrinsic na-

serious that it is not possible to go and Museography set up by the Instituto ture of the objects themselves, which in

through the slow and lengthy process of Technológico Equinoccial has established the last analysis are the be-all and end-all

training personnel with high academic a specialized training course lasting three of the work of a museum.

qualifications, who would have to be re- years, which may be extended for a Ecuador has eighty museums, which

cruited on an unconditional basis, with a further two years in order to reach degree have, for the most part, been established

high probability that they would never in level. The particular interest of this as a result of private initiative in associ-

fact work in the museums in the area. To course lies in its attempt to provide joint ation with the recently founded National

succumb to the temptation to organize training in restoration work and museog- Institute for the Cultural Heritage and

admissions to schools of museology on a raphy. Extension of the course up to de- also with the Banco Central del Ecuador,

liberal basis and allow things to find their gree level, which has already been men- a state-controlled body that plays an

own level on the laisser$aire or laisser- tioned, will give the student the oppor- extremely active part in the country’s cul-

paser principle would, within the Latin tunity to choose in which of these fields tural life (see article by Sergio Durán Pi-

American context, represent an enormous he wishes to specialize. It must be admit- tarque, p. 84). The scene is set for the

waste of effort. This has been amply dem- ted that very often the generalist trend in further development of museology and

onstrated in other fields of activity, the training of museum professionals the recruitment of graduates of the

although it is difficult to understand this tends to provide them with insufficient school by existing institutions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/127332eo-100908150904-phpapp02/85/Development-26-320.jpg)

![Aspects of staff training 93

The Directorate of Museums and been passed. The first unit deals with the 2. Fernanda de Camargo-Moro has pointed out

Monuments in Cuba has introduced humanizing function of small museums that ‘these courses are not sufl6cient to meet the

needs of the roughly 500 Brazilian museums

courses of museology, recently establish- in developing countries and with the spread throughout the country. For a time, Rio

ing for this purpose a School of techniques of gaining a wider public. It would systematically reserve a certain number of

Museology, where specially selected per- lasts a total of 375 lecture hours. The grants eachbut this practice was states of the

federation,

year for the various

dropped a few

sonnel are trained for work in museums. second unit concentrates on the social years ago. The detailed survey of Brazilian

They have been a powerful force in and humanistic function of fine-arts museums which was formerly conducted by the

Association of Members of ICOM-Brazil (Rio de

spreading awareness of the role of the museums and history museums in the de- Janeiro) and is now carried out by the

people in social and economic develop- veloping countries. It lasts 375 lecture ICOM-Brazil Museological Documentation

ment. The School of Museology provides hours, with additional hours for planned Centre, with its headquarters in Rio de Janeiro,

drew attention long ago to the need for training

training in six-month seminars on the or- reading. Finally, the third unit deals with facilities of this kind in other Brazilian

ganization of cultural activities, general science, industrial and technical museums universities in order to meet the growing demand

museology and museography, catalogu- and lasts 375 lecture hours, together with while training atmuseums. It is alsoquite sufficient

of the country’s

university level is

noted that

ing and classification, conservation and additional hours for planned reading. for the purposes of the small museums,

restoration work and Marxist philosophy. A possible change in government pol- postgraduate studies in a in neighbouring or in

museology for graduates

specialized field

After he has finished his studies, the icy could bring about changes in the disciplina are becoming more and more necessary

student of museology is guaranteed con- work of the school if, for example, the for museums with medium- or large-scale

tinued work in museums if his results are government were to encourage the attached to The Arts Foundation of the Museums

collections.

the

General Directorate of

state of

satisfactory, and thus the effort he has put development of science or industrial Rio de Janeiro is attempting to solve this

into his studies is hlly rewarded. museums. This would call for academic problem by organizing practical postgraduate

Finally, mention should be made of flexibility and an organic and functional in conjunction with periodic retrainingaim in so

training courses and

ICOM-Brazil. Its

seminars

the courses that exist in Brazil, including approach that would take political factors doing is to lay the groundwork for the

those given by the University of Rio de in the country into account. In addition, introduction as soon as possible of a master’s

degree in museology.’

Janeiro at the Centre of Human Sciences. it is expected that there will be wide- 3 . As Gretc Mostny has pointed out, ‘Most

These courses, which are undoubtedly the spread job opportunities for the gradu- important, we require trained personnel, capable

longest established in Brazil, are given in ates, both in museum work itself and also of applying the techniques. In many museums,

museography is still improvised, and conservation

the city of Rio de Janeiro itself since in teaching. is non-existent. However, one should be aware of

1932 and also in the city of Bahia. In Finally, it needs to be repeated that, in the dangers of importing models not suited to

the conditions of the country or the region.

both cases, they are at university level and the face of so-called liberal attitudes con- It has been the experience of several countries

are also open to those who are not already cerning admissions of courses, in Latin that sending personnel abroad often has negative

working in museums. The private univer- America and the Caribbean it is never or inapplicable to situationstendthe Third World,

results. The courses taught

in

to be inadequate

sity Estacio de Sa also provides courses at possible to disregard the basic specific and the costly equipment used for conservation,

university level for the training of needs of the institutions concerned, presentation and inventory is much too expensive

museum professionals.2 which in many cases are urgent and re- for these Countries to buy. Often, too, homehighly

trained personnel cannot find a job at

the

on

Courses are also organized in the city quire imaginative solutions.’ Nor can the coming back. This creates frustration and destroys

of São Paulo by the Foundation School of problem of guaranteeing work for those creativity. Many of these people look for jobs in

other arcas, and are lost for the museums.’ For

Sociology of São Paulo, which is linked who have attended such courses be ig- R. C. Ebanks (Jamaica) ‘the best way to achieve

to the university of the same city. This nored, on account of the human and an integral solution to this problem would be to

master’s course for postgraduate students economic d o r t that all this work repre- set up regional training and records centres,

where people educated within the cultural milieu

is divided into three interesting ‘units’, sents for economically weak, developing would organize training courses, wholly applicable