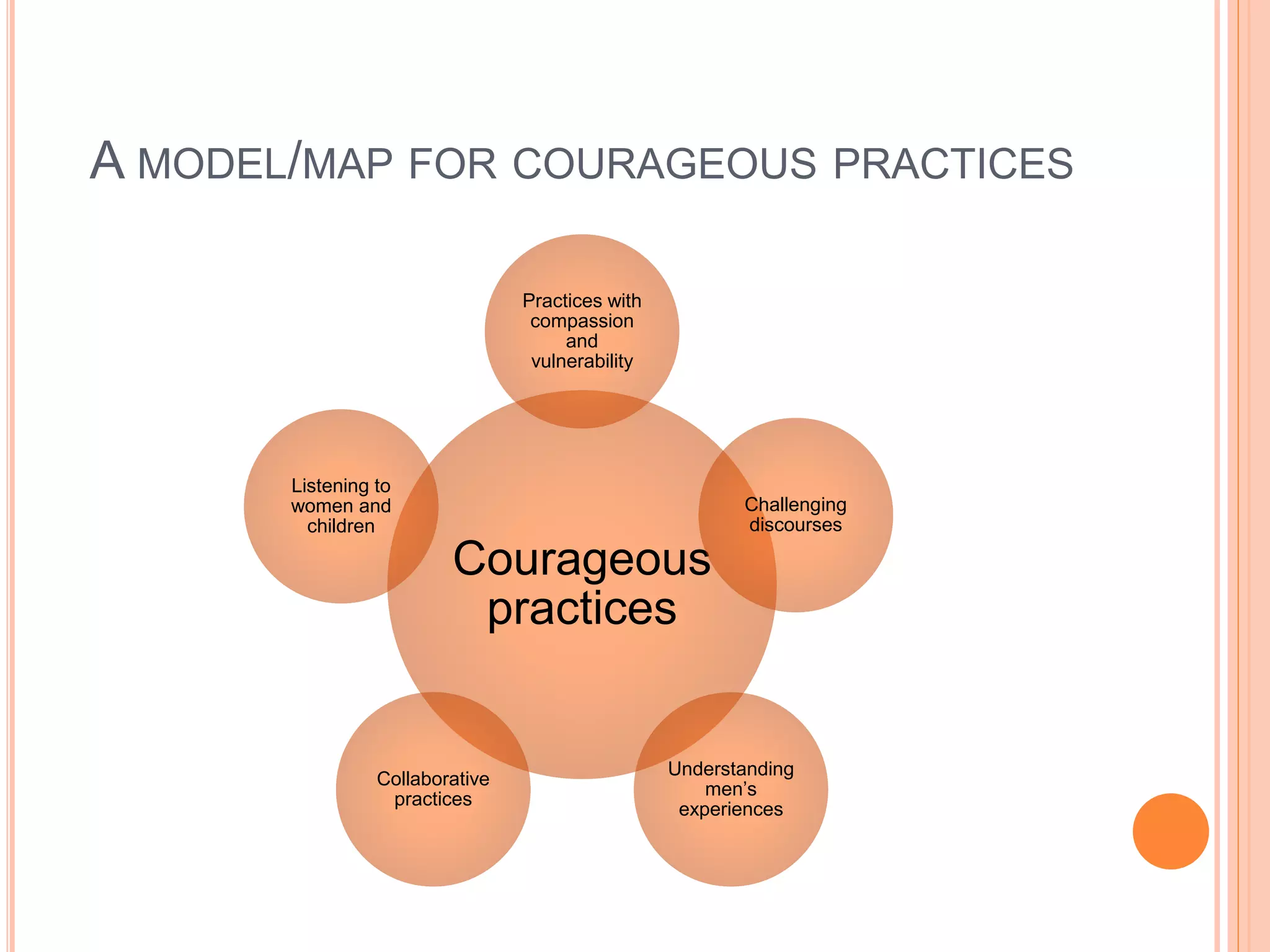

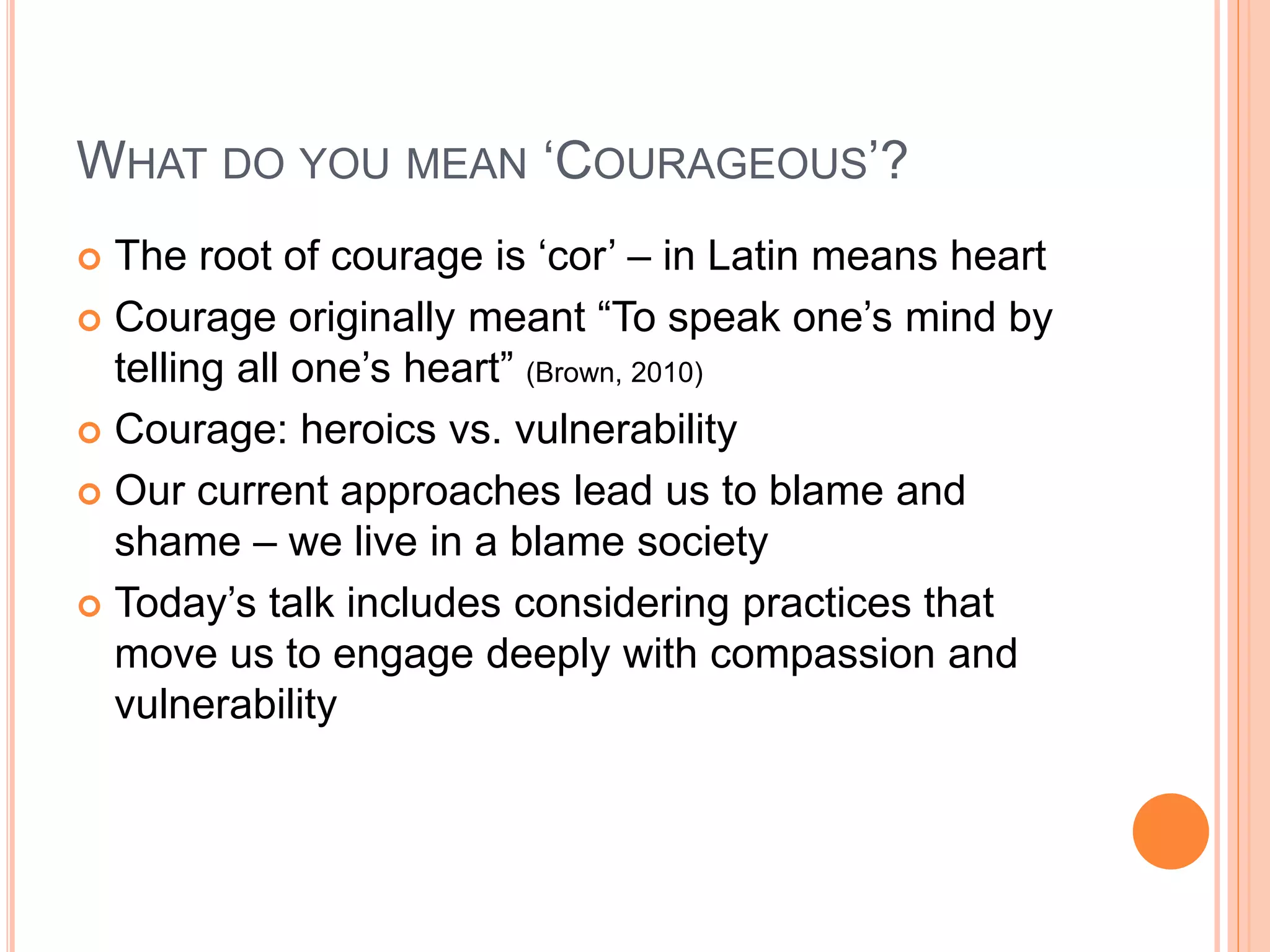

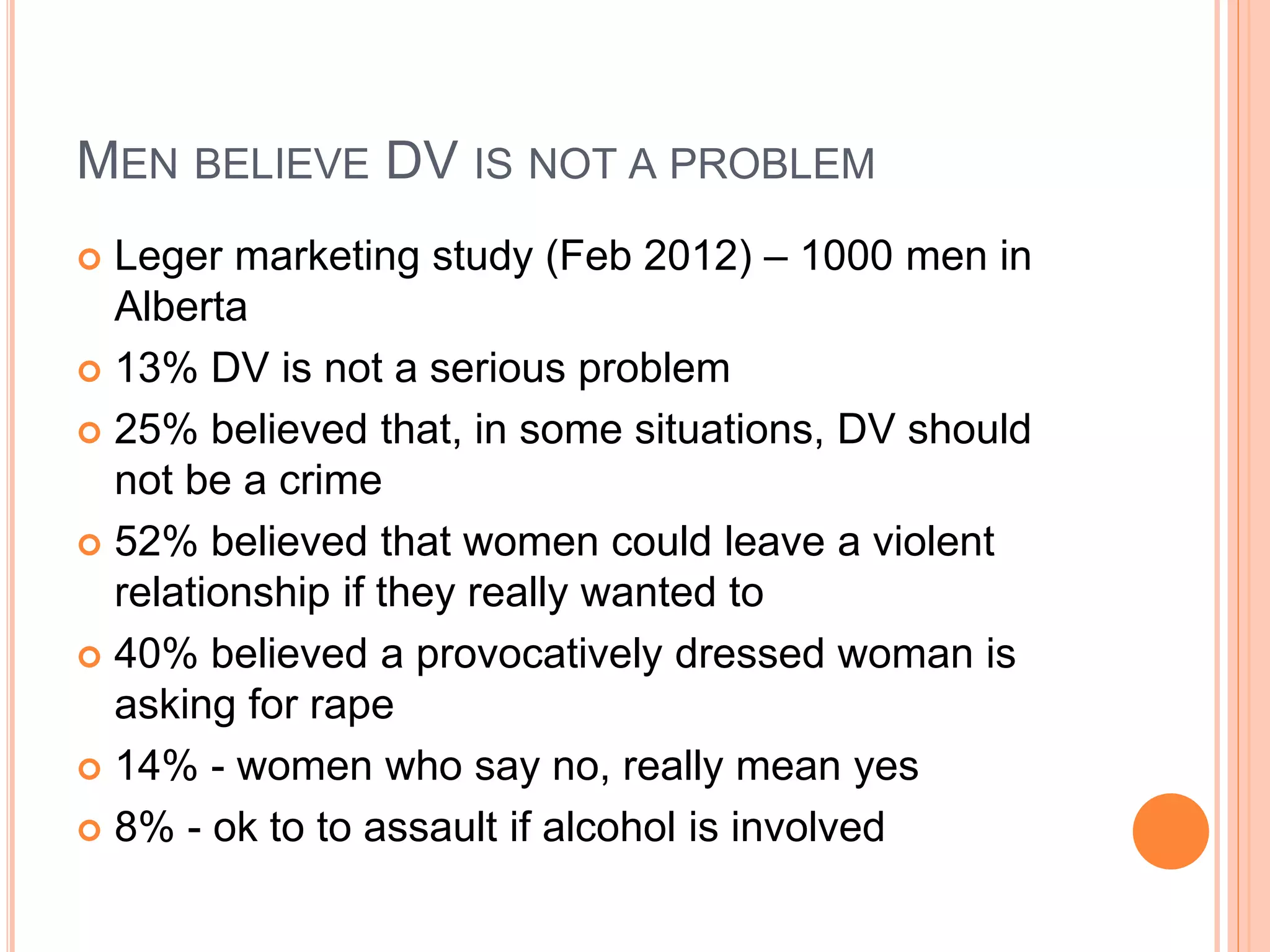

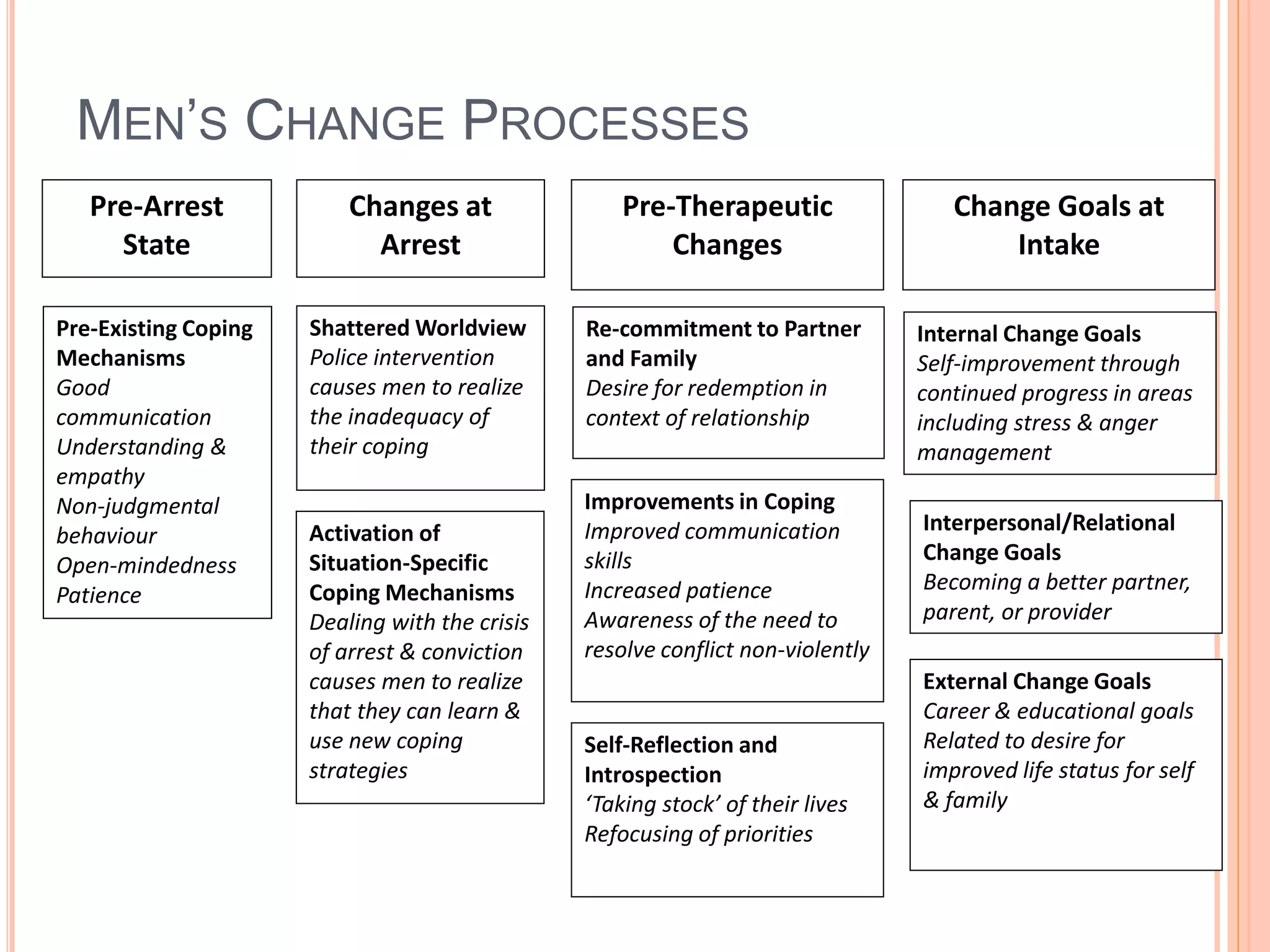

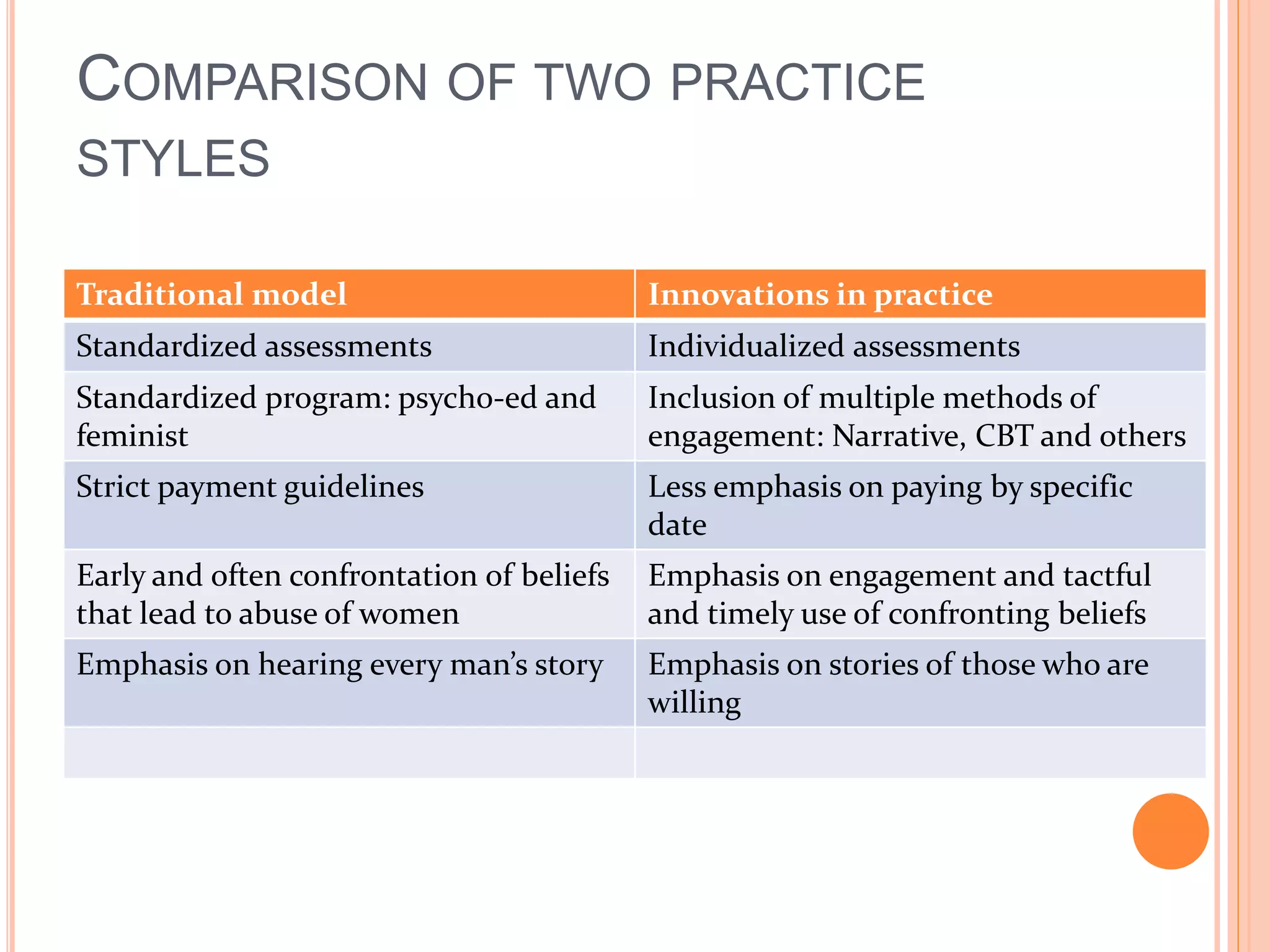

This document summarizes key points from a presentation on courageous conversations about men who abuse. It discusses how current approaches often use shaming language and fail to engage men. Research findings challenge the view that men cannot change, as a study found some men reported positive changes before formal treatment, such as improved communication and commitment to family. The presentation argues for approaches that compassionately support men's strengths and vulnerabilities to foster enduring change, rather than solely focusing on challenging beliefs.