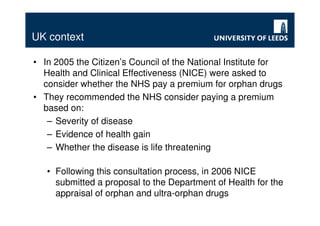

This document discusses orphan drugs and cost-effectiveness analysis in the UK. It notes that drugs for rare diseases are often deemed too expensive based on standard HTA methods. While measures have been taken to encourage orphan drug development, questions remain about whether a premium should be paid for these drugs. The UK's NICE concluded that no changes are needed for drugs treating diseases affecting over 1 in 50,000 people, but may develop special processes for rarer diseases. The document examines arguments for special status for orphan drugs and their implications for resource allocation decisions.