This chapter introduces macroeconomics and provides an overview of key macroeconomic concepts. It discusses how macroeconomics analyzes the aggregate economy, such as total output and price levels, rather than individual markets. It also explains that macroeconomics examines whether markets are performing as they should and how financial systems impact macroeconomic performance. The chapter establishes that macroeconomics studies issues relevant to policymakers and analysts seeking to understand factors like economic growth, prices, and employment on a national scale.

![1.1 Economics from the Micro and Macro perspectives

LO 1.1

LO 1.1 Describe in a broad way the goals of economics and specifically macroeconomics.

Economics has been divided into two sub-disciplines: microeconomics and macroeconomics.

Microeconomics focuses on individuals achieve economic goals, either by themselves or through the

organizations that they form. One economic organization that you no doubt have been exposed to is the

family unit or household. [key word: household: a unit of one or more individuals, often a family, that

reside in the same home.] To sustain the people in the household (that is, the family), individuals must o

perform tasks to produce some good or service.

Some of these tasks are take place entirely within the household -- for example, cooking, cleaning, and

caring for children. Outside the home, individuals commonly form and participate in firms:

organizations/enterprises whose main goal is to produce and sell some good or service that is intended

to be traded in a market. [key term: firm: organizations/enterprises whose main goal is to produce and

sell some good or service that is intended to be traded in a market.] [key term: market: an institution

that brings together buyers and sellers of goods and services.]

Individuals provide their work effort to firms for in exchange for some form of compensation – this is

the income that individuals bring back to their households. [key term: work effort: force exerted by

human beings to produce some good or service.] (Key term: income: resources (goods or money) that

people receive, most often as compensation for producing something.] This income enables them to

buy and consume goods that provide them some pleasure or benefit. [key term: consume: the use of

goods that provide some pleasure or benefit.]

Individuals and the firms they work for each typically produces a relatively narrow range of goods and

services – they specialize. For example, some individuals or firms may be especially good at producing,

say, flat-screen televisions. Others without such detailed technical expertise may, for example, produce

extraordinarily good ice cream.

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-2-320.jpg)

![Figure 1.1

Households and Firms;

Goods and Labor Markets

HH 1

HH 2

LABOR MARKET:

Households supply their

labor to firms; they earn

income as compensation for

their efforts.

Firm 1

Firm 2

HH 3

Firm 3

HH 4

Firm 4

HH 5

Firm 5

HH 6

Firm 6

….

….

GOODS MARKET:

Households purchase and

consume a variety of goods

from firms; each firm

specializes in a limited

number of goods/services.

By contrast, households typically buy a wide range of goods – they do not specialize in consumption.

[key term: consumption: the act of consuming.] As an example, eating ice cream and watching a flatscreen TV are not mutually exclusive activities. In fact, many consumers enjoy eating ice cream while

watching their flat-screen TVs!

Economists emphasize that markets have a key job to do, namely to bring people together so that they

may trade. Figure 1.1 illustrates this point. In markets for goods and services, households, who demand

goods and/or services, are brought together with firms, which supply these goods or services. A market

may be a physical location – a building or tent in some specific place. But, markets may exist in other

forms, including the digital online markets that have evolved in recent decades. In a labor market

individuals who offer their work effort are brought together with the firms who buy that effort. [key

term: labor market: an institution that brings together buyers of work effort (firms) and sellers of work

effort (individuals from households).] 2

2

In some cases, labor markets exist in physical locations. For example, there may be some place in your

town where manual laborers line up each morning get some sort of work for the day – hauling trash,

gardening, painting, etc. More often, labor markets take on a virtual form – a network of contacts in a

certain profession, for example.

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-3-320.jpg)

![In this context, one other kind of economic organization needs to be mentioned. In order to conduct

their market transactions in an orderly way, households and firms require a set of rules by which they

conduct their business, and they need to be assured that the rules are enforced. This is one reason that

states or governments arise: to provide an environment for households and firms to function and

prosper!

Individuals and the firms they work for each typically produces a relatively narrow range of goods and

services – they specialize. For example, some individuals or firms may be especially good at producing,

say, flat-screen televisions. Others without such detailed technical expertise may, for example, produce

extraordinarily good ice cream. .

Households buy and consume goods that provide them some pleasure or benefit. [key term: consume:

the use of goods that provide some pleasure or benefit.] The income they receive enables them to do

so. Households typically buy a wide range of goods – they do not specialize in consumption. [key term:

consumption: the act of consuming.] As an example, eating ice cream and watching a flat-screen TV are

not mutually exclusive activities. In fact, many consumers enjoy eating ice cream while watching their

flat-screen TVs!

In a class on microeconomics, we learn that who produces what will reflect comparative advantage.

[key term: comparative advantage: the capacity of an individual or organization to produce a specific

good or service at a lower opportunity cost than others.] There may be some very talented individuals or

firms that are capable of producing both flat-screen TV’s and ice cream better than others. This

individual/firm is said to have an absolute advantage over others in both TVs and ice cream. [Key term:

absolute advantage: the capacity of an individual or organization to produce a good or services more

efficiently than others]. However, if by dedicating all of their efforts to producing TVs, the cost (as

measured in foregone gallons of ice cream) may be less than others in the market. This individual/firm is

said to have a comparative advantage in TV’s; they will let others produce the ice cream.

Microeconomics thus helps us understand how much of a specific good or service is produced, and at

what price. For both demanders and suppliers of a good/service, a key piece of information is the

market price of that good/service. (key term: demander: an individual or organization that wishes to

purchase a good or a service.] [key term: supplier; an individual or organization that is prepared to offer

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-4-320.jpg)

![a good or a service]. Holding all else equal, an increase in the price of a good/service will encourage

demanders to purchase less but suppliers to produce more. Thus, a key concept in microeconomics is

that the equilibrium price in a market is one where the quantities demanded and supplied of a

good/service are exactly equal. [key term: equilibrium price: the price at which the quantities demanded

and supplied are equal]. 3

If the price of a good/service is (momentarily) below the equilibrium price, the quantity demanded will

exceed the quantity supplied. Producer will be encouraged to produce more in order to meet this extra

demand – but only if the price they receive rises. As this happens, some of the extra demand is choked

off. Ultimately, the price will rise to an equilibrium at which supply equals demand.

From the other direction, if the price is above its equilibrium level, the quantity supplied will exceed the

quantity demanded. Sellers will compete with one another to sell off this excess supply by lowering their

prices. As this happens, more demand is encouraged. This continues until the price reaches an

equilibrium that equates quantities supplied and demanded.

In contrast to the focus of microeconomics on individual markets, macroeconomics puts most of its

emphasis on aggregate concepts and variables – very often, at the level of one or more entire countries.

[key term: aggregate, the combination of many firms and households, most often at the level of one or

more entire countries.] This means that, instead of individual markets (say, ice cream, televisions), we

look at quantities of goods and services produced by the economy as a whole. The most commonly used

aggregate measure of goods and services produced in a country – our output -- is known as gross

domestic product (GDP) – a concept that we will describe more fully in an early chapter of the book.

(Key terms: gross domestic product: the most frequently used measure of a country’s aggregate

output.)

Macroeconomics will focus on measures of an aggregate price level, rather than the prices of one or

several goods. (Key term: aggregate price level: a combined measure of prices of many goods and

services in an economy, as opposed to the price of an individual good or service). A frequently used

measures of the aggregate price level is the consumer price index (CPI). (key term: consumer price

3

If you feel rusty on your supply and demand analysis, don’t worry. We will present an extensive review

in an upcoming chapter.

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-5-320.jpg)

![index: a combined measure of the prices of the many goods and services that households produce].

These concepts – how we measure them and how they are influenced by economic forces -- will be

discussed at length in this book.

Markets: What job do they do -- and are they doing it?

A question that economists often ask is: “Are markets working correctly?” For example, a

microeconomic analysis that focuses on individual goods/services – the market for ice cream, flat screen

TV’s, and so on – tells us the equilibrium amount of each of these goods/services that will be produced.

If the market is working correctly, supply and demand are will be equated with one another at an

equilibrium price. However, something may prevent the market from doing its job. In some cases,

governments may implement policies that interfere with markets. For example, the government might

impose price controls on the price of ice cream. If the controlled price is less than the equilibrium price,

demand will exceed supply. In this case, we can expect that people will form lines to buy ice cream –

especially on hot days! Microeconomics also provides us with the tools to determine whether markets,

on their own, without guidance from the government, will generate a socially beneficial outcome.

In macroeconomics, we often ask questions related to macroeconomic performance. [key term:

macroeconomic performance: a general term which refers several aspects of the aggregate economy,

including (but not limited to) how much output and prices grow]. How is the economy working? Are we

in good times – or bad? Is there prosperity -- or stagnation? Are the benefits of the economy distributed

broadly or only to a privileged few?

When we ask such questions, we also analyze markets. These include the markets for goods and labor

that we just discussed. But, we will discuss other markets that are important for the economy’s overall

performance. We ask whether markets are working correctly –whether they are doing the job they are

supposed to do. If not, why not? Is there some sort of market friction – some feature of the market that

prevents it from working properly? Has the government imposed policies that are detrimental to market

performance? [key term: market friction: some institution, regulation, or other factor that keeps a

market from working correctly.] We will study episodes when macroeconomic performance was poor –

‘bad times.’ It is precisely at these times that we have to question whether markets function – or are

permitted to function – correctly.

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-6-320.jpg)

![Saving, Borrowing, and Finance – A Part of Macroeconomics

An important feature of macroeconomic analysis is that, at any point in time, the amount that individual

units spend need not equal their income. However, in the aggregate, all income must be spent. To see

what this means, let us consider an imaginary economy that has only two individuals, Claire and Bill. As

shown in Figure 1.2, Claire earns 100 but spends only 90. Because she earns more than she spends we

would say that she saves. [key terms; save: to spend less than one’s income] Bill earns 80 and spends 90.

We say that Bill it dissaves. [key terms; dissave: to spend more than one’s income]

Figure 1.2

Claire saves and Bill

dissaves

Saving and Borrowing

Bill

80

90

-10

(Saves)

Income

Spending

Income minus Spending

Claire

100

90

10

Total

180

180

0

(Borrows)

Let us assume that the Claire-and-Bill economy is located on an island in the middle of the ocean. Its two

resident households have no contact of any kind with anyone else. We would call this a closed

economy. [Key term: closed economy: an economy/country that has no economic relationship with any

other economy / country]. In this case, the sum of all the household balances (earning minus spending)

must be zero. We also see that that, in this simple economy, total spending must equal total income -$180.

We can see that, by saving, Claire has provided Bill with the extra resources that he may spend today. If

Claire had spent all of her income, Bill’s spending today would have been limited to $80. Is this a gift

from Claire to Bill? The answer is “probably not”. If you have previously studied economics, or even if

you haven’t, you may have already learned a phrase that economists enjoy using: “There’s no such thing

as a free lunch.” Instead, Claire is likely providing a $10 loan to Bill, rather than a gift. [Key term: loan:

permission to use resources on a temporary basis, with the expectation that such resources will be

repaid.] A loan carries the expectation of future repayment. That repayment will include the original

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-7-320.jpg)

![principal of $10 plus some compensation to Claire in return for the use of her resources today. Such

compensation is called an interest payment on the loan. [key term: interest payment; compensation to

someone who has extended a loan].

A loan is one of many financial contracts or agreements that occur in a modern economy. (Key term:

financial contract: an agreement between savers and borrowers which specifies how much and when a

saver is to be repaid.] The story of Claire and Bill is realistic only if they happen to know one another

personally, and Claire wants to save while Bill wants to borrow. In modern economies with many

people, this rarely happens. Instead, disparate savers and borrowers are most frequently brought

through a bank or other financial intermediaries. For example, Claire places her $10 into the bank in the

form of a deposit. Essentially, Claire has provided a loan to the bank – she expects to be able to reclaim

her money at some point in the future. The bank then lends that same $10 out to Bill. In this case, Bill is

expected to repay the $10 more, but to the bank, not to Claire.

One of the important lessons of macroeconomics in recent years is the critical relationship between

macroeconomic performance and the financial system. [key term: financial system: an economy’s

network of banks and other financial intermediaries] A properly functioning financial system can

improve macroeconomic performance. Sometimes, financial systems can cease to function correctly. For

example, if lenders lose confidence that they will be repaid, they may withdraw from the market. When

many lenders do so, a financial crisis may occur. [key term: financial crisis: a situation where confidence

between lenders and borrowers erodes and the financial system ceases to function correctly.] As we will

discuss later in this book, such crises can have substantial and detrimental impacts on an economy’s

performance. And, the relationship in goes in the other direction: poor macroeconomic performance –

for example low levels of output – can drag down the financial system.

1.2 What’s In It for You? Macroeconomics and Your Life

LO 1.2

LO 1.2 Show how macroeconomics can help you understand concepts that directly impact your

material well-being -- ‘bread and butter’ issues.

You may ask whether studying macroeconomics is worth your time – especially since you don’t plan to

become an economist yourself. But, there are reasons why we would expect that a course on

macroeconomics – and perhaps even this specific book -- may be of interest to you. Perhaps the main

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-8-320.jpg)

![reason is that macroeconomics embraces ideas and concepts that are directly and tangibly related to

your life – including your material well-being.

Gross Domestic Product: A Key Indicator of Our Material Well-Being

As mentioned above, the broadest and most well-known measure of a country’s material well-being is

real gross domestic product (GDP). This is the total economic output of a country -- the total value of all

final goods and services produced in an economy in a period of time. We stress the word ‘final’ since

companies typically purchase inputs (goods and services) to make their product. The difference between

what a firm sells and the inputs it purchases is its value added. [key word: value added; the difference

between what a firm produces and the value of its inputs.] Thus, suppose that a firm sells a shirt for $50,

but that shirt uses $30 worth of cotton. In that case, we would say that the firm’s value added on each

shirt was $20. Thus, GDP is the aggregate variable -- the total of all value added by all firms in an

economy.

The level of GDP is measured in a country’s currency units – the Dollar in the United States is one

example. (Key term: level: the value of a variable at one point in time) We must be sure to use a

measure of measure of GDP that captures as accurately as possible increases or decreases in the

quantity of goods and services that we produce. Economists have developed several measures of real

GDP. [Key term: real GDP; a measure of GDP that permits us to accurately compare values at different

points in time.] Such measures, as we will show in the next chapter, help us know that an increase in

GDP truly reflects an increase in the quantity of goods and services that we are producing. A measure of

nominal GDP, rather than real, GDP, may simply reflect the fact that prices are going up – without any

change in the amount we produce. (key term: nominal GDP; a measure of GDP that does not account for

changes in prices.]

So, GDP is a measure of how much we produce – our output. In what sense is the amount that we

produce connected to our well-being? What does this mean for a country’s citizens? As we will discuss

in greater detail in the next chapter, there is a close correspondence between GDP of a country and the

income that its citizens receive. For the most part, income is the compensation that people receive for

producing something. Then when individuals receive additional income, they have more resources

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-9-320.jpg)

![This has meant that, on a per-person basis, we have steadily increased the amount that we produce and

that we earn over the past 112 years. That is, over the past century, there has been a substantial

increase in our material well-being. In many ways, this has meant a better life for all. Before you opened

this book, you probably knew that we now enjoy substantially higher levels of health and sanitation than

we did in 1900. 4 Basic items like food and clothing are now more abundant than in 1900. For most, the

work that we do now involves much less physical stress and fewer injuries. And, we now have options

for travel and entertainment that were unimaginable in 1900.

WHERE DID WE GET THOSE NUMBERS (algebra only): Calculating Growth

Rates: We can express the increase in per capita GDP as a number. The

Baseline

alt(i)

alt(ii)

Where did 13260 get those

we

13525

13931

numbers? 2.4

3

2.9

Output

Inflation

Interest Rate

4.5

4.7

4.6

calculations are summarized in Table 1.1. Note that, at the last point of our

data, in 2009, we produced about $42 Thousand per person. At the start of our data, in 1900, we

produced about $5.6 thousand per person. Hence, when we do a division 43.3/5.6, we obtain a result of

7.79. That, in 2009, the US produced almost 8 times on a per-person basis than it did in 1900.

Throughout this book we will be making calculations like this and expressing them in terms of growth

rates that are expressed in percent. For any variable X, the growth rate will be calculated as

%ΔX = XLATER / XEARLIER -1

(

1

.

Hence, in percent (%) terms, per capita income has grown by over 679% (43.3/5.6-1 is about equal to

6.79). This growth has occurred over a period of 112 years (2012-1900). Thus, we can how to calculate

1

the growth rate on an average yearly basis: 5

)

%ΔX(Yearly average)=[(XLATER /XEARLIER )1/N.of Years ]-1

(

1

.

2

4

As one example, we now take for granted that our houses will have indoor plumbing. This convenience

)

was developed during the mid-1800s, but did not become universal in the US until well into the 20th

Century!

5

You might be tempted to simply divide 660 percent by 112. However, you would not get a correct

answer since growth rates are compounded over time.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-12-320.jpg)

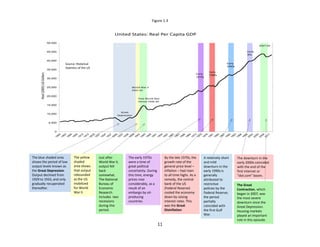

![a period of economic stagnation that began in 1929 and extended through most of the 1930s.) This was

a period of economic stagnation that began in 1929 and extended through most of the 1930s, with percapita GDP bottoming out in 1933. The term ‘depression’ is often used in geology to denote a valley,

canyon, or dry lakebed. Hence, the term ’depression’ It is an appropriate metaphor for economics: over

the years 1930-34, GDP per capita is 18% lower than it was during the previous 5 year period (1925-29).

From its bottom in 1933, output increased only gradually – until 1941, when the US entered World War

II. At that time, the federal government coordinated efforts to increase production related to the war,

which lasted until 1945. Then, in 1946, just after the armistice, as the US wound down its wartime

efforts, real per-capital GDP again dropped by -- 11% in one year alone.

After this, and into the decades of the 1950s and 60s, the nation enjoyed a period when output grew

more steadily than in previous years. However, the 1970s brought in a period of great political and

economic uncertainty. An embargo by major petroleum exporters (the Organization of Petroleum

Exporting Countries, or OPEC) sent oil prices skyrocketing in 1973 and again in 1979. Civil unrest was

brought on by the Vietnam War. For the first time, a sitting US President, Richard M. Nixon, was forced

to resign as a result of misdeeds in office. Again, at the end of the 1970s and during the early 1980s,

GDP per-capita stagnated; oil prices surged again, and world economies struggled to defeat inflation – a

rise in the price level that continues over time. [key term: inflation; a rise in the price level that

continues over time. ] We call this period during the early 1980s the Great Disinflation. [key term: Great

Disinflation; a period during the late 1970s and early 1980s when inflation, which had been high in

previous years, was brought down.]

The slowdown of 1990-91 (associated with the first Gulf War), and in 2000-01 (associated with the burst

of the “Dot-com” bubble) are also evident. But, most readers of this book are probably more directly

familiar with the economic slowdown that began in 2007 and the meltdown – both financial and

economic – that took place in 2008-09. We will discuss this most recent episode, which we call the Great

Contraction, in the next section of this chapter. [key term: Great Contraction: the fall in economic

activity, associated with a financial crisis, that began in late 2007 and continued through 2009.]

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-14-320.jpg)

![Employment and Unemployment: Will I Get A Job?

It should not surprise you that a growing economy will generate more job opportunities than a stagnant

one. Businesses that produce more and sell more will typically employ more people. Thus, your personal

opportunities are most likely tied to the economic well-being of the country. When you leave school,

you will probably join the labor force – individuals above 16 years who are working or want to work.

[key term: labor force: individuals above 16 years who are working or want to work.] If you get a job,

you will be counted among individuals who are employed ; until you do so – and it you will most likely

have to look – you will be among the unemployed. [key term: employed: in the labor force currently in a

job.] [key term: unemployed: in the labor force, but without a job – but looking for one.]

The percentage of the labor force that is looking for a job but do not have one is called the

unemployment rate . [key term: unemployment rate: the fraction of the labor force that is currently

unemployed.] This number for the US is shown from 1900-2009 in Figure 1.4.b (bottom panel) in

percent. GDP per capita for the corresponding period is shown in Figure 1.4.a. (top panel). We can see

how unemployment surged during Great Depression, reaching 23% in 1932. After the Great Depression,

we see episodes where the unemployment rate surged, although not as severely. We can see that

episodes of higher unemployment coincide, for the most part, with the economic downturns that we

introduced in the previous figure.

You may be tempted to think about such changes in the unemployment rate in terms of supply and

demand – concepts which you may be already familiar with. If so, your intuition would be, to a large

extent, correct. During good times, firms demand more labor. When economic activity slows down, they

demand less. Hence in some sense, we might think of unemployment as simply the difference between

labor supply and labor demand.

However, the chart tells us that we have to be careful about the timing. The unemployment rate

typically peaks after the most severe part of the slowdown – just when the economy is beginning to

recover. Why might this happen? When the economy first slows down, employers may be reluctant to

lay off workers – especially their most valued ones. Then, as the slowdown gets under way, some

employers find that they cannot fund their payroll, so they lay off some employees. Then, while an

economic recovery is in a tentative stage, employers may reluctant to take on long term commitments

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-16-320.jpg)

![when they rehire, and some hire only on a temporary basis. However, when entrepreneurs are more

confident about the economy’s future, hiring occurs more rapidly and the unemployment rate falls.

In this book, we will devote some time to studying labor markets. We will find that the tools of supply

and demand analysis are critical to understand the relationship between output and unemployment. At

the same time, we will find that labor markets have some features not found in other markets. For this

reason, we will need to adapt our supply and demand tools to capture the realities of labor markets.

However, we will find that main job of a labor market is to bring together employers and employees.

Sometimes, labor markets do not do this job well; sometimes there are policies that prevent the labor

market from doing this job well. When this happens, the result that we often see is unemployment that

is higher and longer than need be. As we see below, the Great Depression provides an important, if

tragic, case study where labor markets did not (or were not permitted) to function well. For this reason,

unemployment remained high during the Great Depression – for a considerable period of time.

How much does it cost to live? The Consumer Price Index and Inflation

Nearly everyone is concerned with the cost-of-living. Households can suffer when the prices of key

goods and services they buy rise – if their income does not keep up. Most countries measure the cost of

living by constructing a consumer price index (CPI).

To do so, economists first determine the bundle of goods and services that households typically

purchase in a period of time – food, clothing, housing, domestic services, transportation (including gas,

oil, and upkeep on the family car), entertainment, and so on.

7

The prices are combined into a price

index that attempts to reflect what an “average” or “typical” consumer purchases. [key term: price

index; a combination of several prices that is used to measure the aggregate price level.] The CPI is

often reported in terms of its growth rate in percent over some previous period. This is a measure of

the inflation rate. [key term: inflation rate; the percent growth of prices over the previous period; used

interchangeably with ‘inflation.’] So, if we say that “The Inflation rate is 5% per year,” or equivalently,

“Inflation is 5% per year,” we mean that the CPI is 5% higher today than it was one year ago.

7

In the United States, the CPI is constructed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-17-320.jpg)

![Figure 1.5 shows inflation for the US since 1947. We can see that (headline) CPI inflation was high and

volatile in the initial years – just after World War II had ended. During the early 1960s, both inflation

rates were low – less than 2% per year. Then, inflation creeps up – first spiking at just over 6% around

1969 and then spiking twice: first at about 12% per year in 1974 and then at over 16% in 1980.

Figure 1.5

US: CPI Inflation

In percent per year

16

14

12

In Percent year-over-year

10

Headline

8

6

4

2

0

1948

1953

1958

1963

1968

1973

1978

1983

1988

1993

1998

2003

2008

2013

-2

Source: US Bureau of

Labor Statistics

-4

This graph suggests to us in another way why the 1970s were considered a period of economic

turbulence. Not only was inflation high, it was also less predictable than previously. This made it more

difficult for households and businesses to make plans. The graph also shows how inflation came down

during 1980s and 1990s. In this book, we will discuss several explanations as to why this happened. We

can also see that during late 2008 and 2009 inflation became negative. The overall price level (including

both food and energy) dropped by about 2%. From the outset of the financial crisis in 2008, policy

makers were worried about a protracted fall in consumer prices – a deflation. [key term: deflation: a

continued fall in the price level; minus one times inflation.] The concern is that, under a deflation, when

people expect prices to drop in the future they may delay their purchases until they can benefit even

more from lower prices. Hence, the danger of deflation lies in the possibility that demand and prices

might pull one another down in a vicious downward spiral.

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-18-320.jpg)

![It is not possible to talk about inflation without mentioning in institution that exists in most countries: a

central bank. [key term: central bank: a public, or partially-public institution whose main responsibilities

include the maintenance of a stable rate of inflation]. Central banks are typically part of the

government. However, in most countries, the central bank has been granted some independence from

day-to-day political affairs. In the US, the central bank is called the Federal Reserve (or more commonly,

the ‘Fed’.) 8 Central banks issue a financial instrument that we use every day to conduct our

transactions: money. (key term: money: a financial instrument used for day-to-day transactions and that

performs several other functions.) In this book we will learn how the policies of the central bank,

including how much money they issue, will have an impact on the inflation rate.

How Wealthy Are We? Stock Market and House Values

The assets that people hold, in addition to the income that they earn from their employment, represent

resources that are available for them to spend and enjoy. [key term: asset; a resource held by some

person, household, firm, or country that confers and economic benefit.] There many different kinds of

assets – too many to discuss here. However, there are two kinds of assets in particular that you are

probably familiar with and whose value can be substantially impacted by macroeconomic events.

First, many households own equity shares. [key term: equity share; a financial instrument that grants

someone the right to some portion of a firm’s earnings; equity shares are commonly known as “stocks”.]

They may have purchased stocks in a direct manner, buying and selling online or through a stock broker.

Or, they may hold equity shares indirectly, through a mutual fund or a retirement plan. - By owning

equity shares in a firm, households can participate in the fortunes of that firm – good or bad. When a

firms profits increase (or are expected to increase in the future), the household benefit because the

equity share price (or stock price) rises. When a firm’s profits decrease (or are expected to decrease in

the future), the household loses because the equity share price (or stock price) falls.

8

Several countries may join a monetary union. [key term: monetary union; multiple political units that

use the same money]. In this case, they will be served by one central bank. For example, members of the

Euro area (17 European countries in all) are served by the European Central Bank (ECB). In most

countries or monetary unions, the central bank operates under a mandate or charter whose primary

goal is to make sure that the aggregate price level remains firmly under control . (key terms; mandate,

charter). However, in most countries, central banks will have other, broader goals that are related to

improving the country’s economic performance.

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-19-320.jpg)

![Equity shares are traded on a country’s stock market (or stock exchange). [key term: stock market: an

institution that brings together buyers and sellers of equity shares; the most well-known example of a

stock market in the United States is the New York Stock Exchange.] Equity share prices of many

companies are put together and published daily as stock price indices. (key term: stock price indices).

You may already be familiar with the idea of a stock market, including the widely used indices such as

the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), the Standard and Poor’s 500 Index (S and P 500), and the

NASDAQ Composite. 9

Stock price indices thus reflect the sales and income prospects of many firms in an economy. In this

sense, these indices – often referred to in the popular press and the “stock market” can serve as an

important barometer of broader the macroeconomic picture. When things are going well in the

economy, firms will sell more goods and services. This is precisely when more people will want to own

equity shares in firms, since their goal is to participate in firms’ good times. Accordingly, prices of equity

shares rise. In the other direction, when things are going poorly in the economy, firms sell less. In this

instance, people will sell their equity shares, and their prices fall.

But, there is another linkage between stock markets and the economy. As we will discuss later in this

book households who are fortunate enough to hold equity shares when their value rises have essentially

received some extra income – so they spend more. In the other direction, when equity share prices fall,

these households tend to spend less.

The other asset of importance to families is real estate – for example, their house. For many individuals

In many case, a house is an individual’s main asset. While people live in their homes, most recognize

that, if they needed to, they could sell their house for cash. They may see the connection: higher house

value, more cash. This line of thought, of course, is incomplete: it ignores where else they might live if

they did sell their house.

9

The acronym NASDAQ originally stood for National Association of Securities Dealers Automated

Quotations).

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-20-320.jpg)

![Most individuals/families do not have the resources to purchase a home outright. Instead most rely on

borrowed funds in the form of a long-term mortgage loan. [key term: mortgage; a long term loan that is

extended, most generally for the purchase of a house.]. As is the case with other loan, recipients of a

mortgage are expected to repay their lender a specified amount on specified schedule. In this case the

value of the house can take on more importance. Home owners with mortgages are (or should be)

aware of whether their house value exceeds their loan value. No one wants to be “under water” – a

situation where the loan is worth more than the house itself!

You were probably familiar with these assets before you opened this book. Your personal situation, or

that of your family, may have been impacted by recent shifts in the stock market and the real estate

market. What you may not be aware of are the many linkages between assets like equities and real

estate and broader macroeconomic concepts. We will discuss such linkages in this book. To begin,

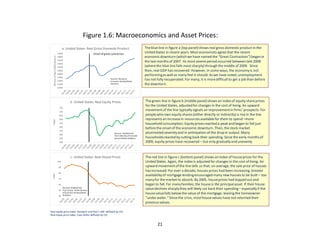

Figures 1.6.a and 1.6.b illustrate some of these linkages during recent years in the United States. In

Figure 1.6.a (top panel), the blue line shows real gross domestic product in the United States in recent

years.

As discussed previously, the recent economic downturn (which we have named the “Great Contraction”)

began in the latter part of 2007. Its most severe phase began in late 2008 (where the blue line falls most

sharply) and lasted through the middle of 2009, when output bottomed out and began to recover. Even

though real GDP has returned to its pre-downturn values, some aspects of macroeconomic performance

remain subpar. Perhaps the key example is unemployment, which had not recuperated even four years

after the downturn ended. For many, getting a job is problematic – much more than before the

downturn.

In Figure 1.6.b (middle panel), the green line shows a well-known index of equity share prices for the

United States, the Standard and Poor’s 500 index. The index is said to be a “real” index because adjusted

for changes in the cost of living. You will learn how to make such an adjustment in this book. An upward

movement of the line typically signals an improvement in firms’ prospects, while a downward

movement signals a deterioration. For people who own equity shares (either directly or indirectly) a rise

in the line represents an increase in resources available for them to spend – more household

consumption; a downward movement means fewer such resources.

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-22-320.jpg)

![and services]. The three most frequently cited factors are land (T – from the Latin ‘terra’), the labor

force (L) and capital (K). [key term: capital: a factor of production that itself is produced by humans,

often (but not exclusively) refers to the plant equipment held by firms.) Capital is often (but not

exclusively) used to refer to the buildings, machinery, and other goods that firms use to produce their

good or service. To analyze how these three factors are combined to produce output, economists use

yet another simplification of reality – a production function. [key term: production function: a compact

way of describing the process of producing goods and services that economists use in their analysis.] A

larger labor force, with more people going to work, will raise output. Likewise, higher labor quality in the

form of better educated workers with better work habits will also mean higher output. If countries

dedicate more of their resources to increasing the productive capital, output will also increase.

We sometimes find while two different countries that each use similar amounts of land, labor, and

capital but produce very different levels of output. What makes some countries more productive than

others? Empirical research suggests that certain institutions and policies have important impacts on

productivity. The institutional framework in some countries may provide a more favorable environment

for growth. An example: countries with less corrupt governments tend to grow more than their more

corrupt counterparts.

The answers to such questions should help determine what policies are taken. Hopefully, economists,

like doctors, would first wish to ‘do no harm.’ They would hopefully wish to avoid implementing policies

that reduce growth. Beyond that, economists should also hopefully have something to say about the

kinds of policy reforms that would help boost growth.

Issue II: Output and Price Stabilization: Is our country’s output “too high” or “too low” relative to its

normal (or potential) level? What are the implications for inflation? If so, what (if anything) should

policy makers do?

There is a broad consensus that any point in time there is some normal or potential level of output for

an economy. [key term: potential output: the level of output that corresponds to the long-run constraint

implied by the production function, with land, labor, and capital all used a long-run or normal levels.]

Most economists would agree that the potential output corresponds to the long-run constraint implied

by the production function, with land, labor, and capital all used at their long-run or normal levels.

When output is less than its potential, factors of production are used at below-normal levels.

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-28-320.jpg)

![Stabilization policy can be also be important is when the economy is overheating – when output

substantially exceeds its potential and inflation is rising. [key term: overheating; a metaphor used to

describe an economy whose output is substantially above potential and, in some cases, whose inflation

rate is rising] Unless the authorities reduce demand, by putting on the policy ‘breaks’ (with monetary

policy typically implemented more quickly than fiscal policy), inflation may rise to undesirable levels and

may even spin out of control.

Issue III: External Balance: Is our country importing too much and/exporting too little (or vice versa)?

Are we living beyond our means and borrowing too much from foreigners?

In recent years, the economy of the United States has become increasingly integrated into the world

economy. We have been selling more to the rest of the world. As Figure 1.8 shows, our exports (sales of

goods and services to the rest of the world) were just under 10% of GDP in 1991. [key term: exports:

sales of goods and services by one country to the rest of the world]. By 2010, after recuperating from

the world downturn, our exports had grown to about 12½% of GDP. Likewise, our imports (purchases of

goods and services from the rest of the world) were just over 10% of GDP in 1991. By 2010, our imports

had grown to about 16% of GDP.

11

[key term: imports: purchases of goods and services by one country

from the rest of the world].

Figure 1.8

United States: Exports and Imports

In percent of GDP

20

15

in percent of GDP

10

Net Exports

5

Exports (Goods+Services)

Imports (Goods+Services)

0

-5

Source: IMF/IFS

-10

In fact, United States’ imports have far outpaced exports. The gap between exports and imports, known

as net exports (or interchangeably the trade balance; net exports = exports minus imports) has become

11

The services include transportation, tourism, insurance, communications, and license fees. How we

compute exports and imports – the balance of payments – is discussed in Chapter _.

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-30-320.jpg)

![increasingly negative – a trade balance deficit. [key term: net exports: the difference between a

country’s exports and imports; also known as its trade balance]. [key term: trade balance: equivalent to

net exports].

If exports exceed imports, we say that the country is running a trade balance surplus. If we measure

everything accurately there must be a one-to-one linkage between one country’s deficit and a

corresponding surplus for the rest of the world. 12

Many economists have suggested that there are risks associated with the large deficits for the United

States and large corresponding surpluses for China and other countries. Such global imbalances surely

have had impacts in the everyday lives of citizens.[key term: global imbalances: the large deficits of the

United States observed during the 1990s and early 2000s that correspond to large surpluses in other

countries.] In the US, consumers have enjoyed an abundance of imported goods from China (and other

‘emerging markets’ in recent years) -- electronics, clothing, footwear, toys, sporting goods, and so on.

From the Chinese perspective, export-related jobs have helped lift many Chinese workers out of

extreme poverty.

As a country such as the US continues to run external (trade balance) deficits, it accumulates ever more

obligations to the rest of the world – including external debt. [key term: external debt: a country’s

borrowed obligations to the rest of the world.] A country’s external debt cannot grow forever. For this

reason, the global imbalances that we now observe cannot last forever.13 Just as a country’s output will

return to its normal or potential level, its trade balance will also return, from a position of imbalance’ -a deficit or a surplus that is ‘too high’-- to a more balanced position.

12

That is, suppose there are three countries in the world, A, B and C. If country A’s net exports are -5

and country B’s net exports are 2, country C’s net exports must be 3. Thus, the sum of net exports for A

plus B plus C must sum to zero – if measured correctly. In reality, the actual data for the world does not

add up. This situation led some facetiously speculate that the planet Earth is running a deficit with the

planet Mars.

13

Economists have long recognized that the stability of a country’s output level (Issue II) and its external

accounts (Issue III) are parallel issues and cannot be in isolation of one another. This view is associated

with the work of Robert Mundell, a Nobel Prize Winner in Economics (see Mundell, R. , 1962,“The

Appropriate Use of Monetary and Fiscal Policy for External and Internal Stability,” IMF Staff Papers,

March, pp. 70-79.)

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-31-320.jpg)

![How will these imbalances be resolved? Will the United States be able to repay its debt? Will other

countries, including China, continue to lend to the United States – even if its debt obligations continue

to grow? If the United States’ external debt becomes too high for it to repay, will the country be able to

negotiate some sort of orderly work-out with lenders such as China? Or, in a less-orderly manner will the

United States unilaterally repudiate its debt, potentially causing market participants to lose their

confidence in the United States economy. Will such events bring about an externally-based crisis and

perhaps another Great Depression? [key term: externally-based crisis: a loss of confidence by the rest of

the world in a country’s economic policies or capacity to repay its external debt; such crises can often

lead to severe economic downturns.]

Figure 1.9

United States: Public Debt/GDP

in percent

120.00

Peak of debt ratio after

World War II.

Alternative

scenario by

independent

analyst.

100.00

In percent of GDP

80.00

Data prior to

2012 is historic.

60.00

Official

(CBO)

baseline

scenario

40.00

20.00

0.00

1940

1945

1950

1955

1960

1965

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

2015

2020

Source: Congressional Budge Office, Long Term Budget Outlook May 2013; alternative

scenario reflects author's calculations. Measure is debt held by the public.

Issue IV: Public Sector Budget Balance: Will our country’s government be able to service its financial

obligations?

In the aftermath of the recent recession, government deficits – the excess of the government’s

expenditures over revenues -- grew dramatically in many countries, including the United States. As GDP

dropped, so also did tax revenue -- a government’s main source of income. [key term: tax revenue (or

taxes); resources that the government collects from households and firms in order to fund its

expenditures.]

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-32-320.jpg)

![At the same time, in some countries, certain kinds of spending, including social safety net expenditures

designed to help the least advantaged households, including unemployment benefits, also rose during

the downturn. [key term: social safety net expenditures: spending targeted toward helping the least

advantaged households; a prime example is unemployment benefits] In the United States, a newlyelected government under President Barack Obama passed a fiscal stimulus package of temporary

spending increases and tax cuts with the aim of bolstering the aggregate demand for goods and

services. [key term: fiscal stimulus: increases in expenditures or reductions of taxes that the government

makes with the intent of stimulating economic activity during periods of weak output.][key term:

aggregate demand: the demand for all goods and services, in the aggregate.] That package contributed

tangibly to US government debt: it totaled $787 billion dollars (just below 6% of a single year’s GDP).

When a government runs a deficit its debt increases. Figure 1.9 shows how US government debt as a

fraction of GDP has evolved since 1940. The chart shows that the government had to borrow

considerably to finance World War II. In 1947, the debt ratio peaked at around 108% of GDP before

gradually falling to about 28% in the early 1970s. [key term: debt ratio: the ratio of government debt –

its accumulated borrowings – to gross domestic product.]

Unlike the other charts shown in this introductory chapter, this one also shows a projection of the debt

ratio – a prediction of where that number may go in the future. [key term: projection: an educated

guess or prediction of what may happen in the future based on specific assumptions.] The Congressional

Budget Office (CBO) of the United States is charged with providing such likely scenarios of prospective

government income, outlays, and government debt. Such forecasts are provided to help the

government plan its policies.

Under a scenario that assumes that current policies remain in place – a baseline scenario -- the debt

ratio is forecast to rise to almost 80% of GDP by 2023 – a figure that has not been seen since early

1950s. [key term: baseline scenario: a projection that shows the most likely outcome, in the opinion of

the experts who make the economic assessment.]

As you might imagine, things might not evolve as the CBO envisages. Things may go worse. The

government may spend more money – say on an unexpected war – or its tax revenues may fall for some

reason. For this reason, analysts often also prepare an alternative scenario that shows what might

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-33-320.jpg)

![happen under alternative, less favorable circumstances. Under the scenario shown in the chart,

presented by an alternative analysis, the debt grows each year somewhat more than under the baseline.

However, by 2023, the debt will have risen, under this scenario, to over 100% of output – number that

the country has not seen since World War II! [key term: alternative scenario; a projection that shows

the an outcome that is less likely than the baseline scenario but likely enough for people to pay

attention to, in the opinion of experts who make the economic assessment.]

Government debt (in relation to a country’s output) cannot rise forever. If public debt level remains at a

manageable level, the government will be able obtain resources sufficient to cover its interest

payments. In the most hopeful of cases, a more productive economy will provide more tax revenues –

the country can grow its way out of its fiscal problems. As we will learn in this book, if the economy is

more productive, it can manage its debt more easily.

However, very few governments can simply grow their way out of fiscal difficulties. Instead,

governments that face problems of mounting debt typically face tough choices – what to cut, what taxes

to increase. Often, the outcome of such policies will bring about added hardships for the least

advantaged members of society.

What if the government fails to make such tough choices? The market may lose confidence that the

government will be able to repay its debt in the first place. Historically, some governments in this

situation have resorted simply printing more money as a way to pay the debt. When this happens,

inflation typically jumps out of control, as the central bank loses control of the price level. Hence, the

take-away here is that growing government debt means that the country faces tough choices.

Issue V: Financial Sector Soundness and Vulnerability: Will our country’s households and firms be able

to service their obligations that reside in the financial system? Will the financial system be able to

perform its job – to bring together surplus and deficit units in an efficient way?

To see how finance permeates macroeconomics, we can begin with a simple story of a households and

commercial enterprises. Households are assumed to be surplus units: they earn more than they spend -today. By contrast, commercial enterprises have projects that may successfully produce goods and

services for the market – but only in the future. Such projects will require resources ‘up front’ in order to

acquire inputs (including capital) that enable them to produce their goods.

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter1-140216034541-phpapp02/85/Chapter1-34-320.jpg)