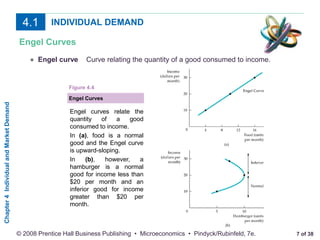

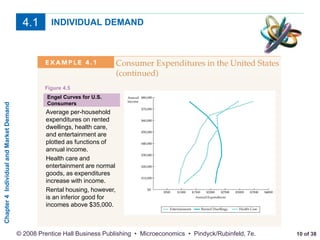

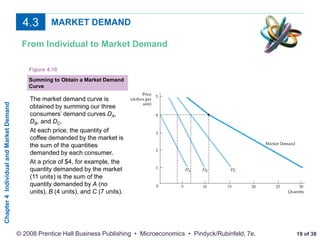

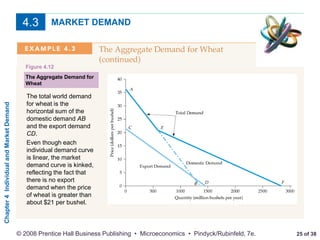

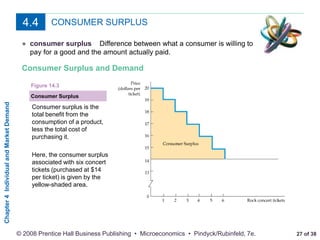

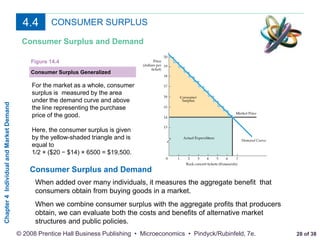

This document discusses individual and market demand. It begins by explaining how an individual's demand curve is derived from their price-consumption curve and how it shifts with changes in income and prices. It then discusses the concepts of substitution and income effects that occur when prices change. Finally, it explains how market demand is constructed by summing individual demand curves and how demand elasticity is measured.