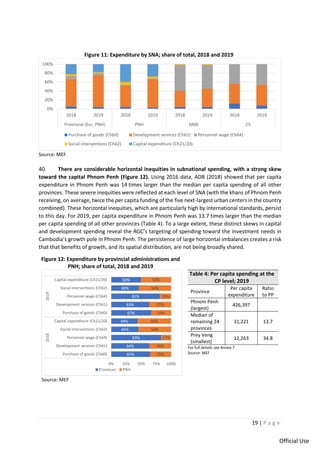

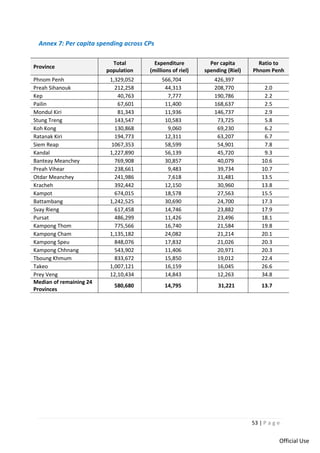

This document provides a summary of Cambodia's intergovernmental fiscal architecture based on a study of decentralization reforms. Key points include:

1. Cambodia has pursued decentralization reforms since 2001 to improve governance, establishing a three-tiered subnational administration system.

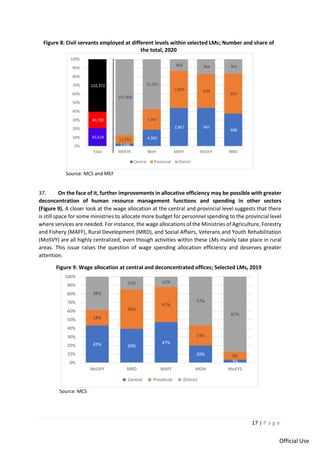

2. Implementation of decentralizing functions from central to subnational levels has been slow and piecemeal. Most functions were transferred to the capital/provincial level, with limited transfers to the district/municipality level until recently.

3. In 2019, the government instigated reforms to accelerate decentralization, including transferring 21 functions across five line ministries mainly to capital/provincial levels. Additional reforms integrated 13 deconcentrated line offices into the