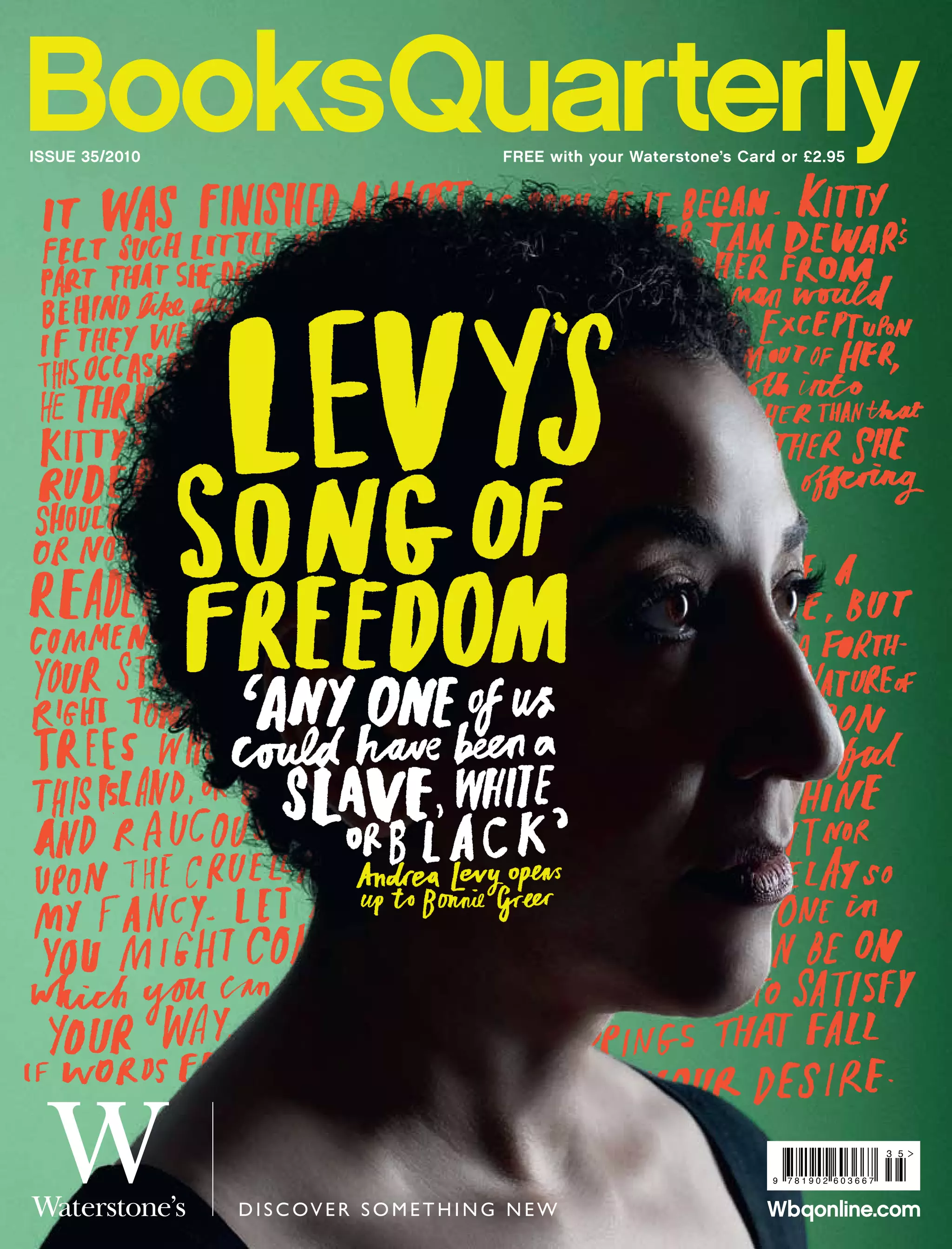

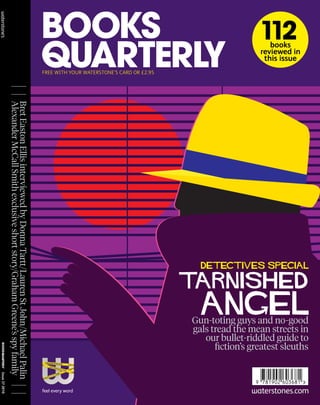

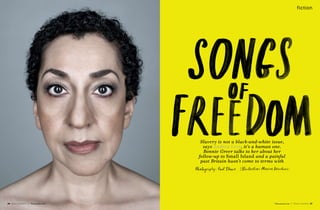

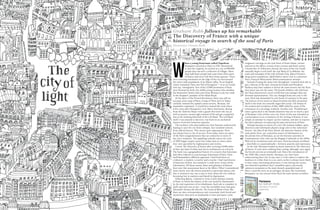

This document provides a summary of several articles from a publication called Books Quarterly. It discusses novels by authors such as David Mitchell, Orhan Pamuk, and Graham Robb. Specifically, it summarizes interviews with these authors about their latest works, including Mitchell's historical novel set in Japan, Pamuk's novel exploring Istanbul in the 1970s-80s, and Robb's "adventure history" of Paris told through short stories. It also previews novels by several new British authors and provides an overview of the enduring appeal of detective fiction and some of its most prominent authors.

![6362

Your next read

You Are Not a Stranger Here is the

obvious place to go: Haslett’s

stories have all the humane

depth of his novel, and he

handles the darkest of states

– grief, depression, madness –

with honesty and empathy.

A class apart

Haslett’s a graduate of the Iowa

Writers’ Workshop, America’s

leading creative writing

programme. Alumni include

Curtis Sittenfeld, Nathan

Englander, Steven Erikson

and Flannery O’Connor.

The book

Union Atlantic tells of a feud

between retired history teacher

Charlotte Graves and banker

Doug Fanning, as a financial

crisis rumbles beneath them.

It’s a wide-ranging look at

modern American life.

Union

Atlantic

by Adam

Haslett

Tuskar Rock

£12.99 July

intro ducing adam haslett

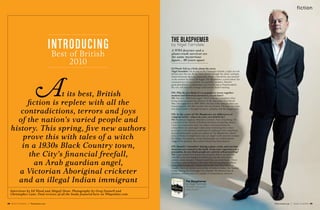

A bold new claimant to the Great American Novel, Adam Haslett’s post-9/11,

pre-credit crunch first novel is an assured start, says bookseller Greg Eden

Adam Haslett burst on to the literary

scene in 2002 with his debut collection

of stories, You Are Not a Stranger Here,

which quickly captured the imagination

of critics and was shortlisted for both

the US’s National Book Award and the

highly prestigious Pulitzer Prize. It won

praise for its immaculate storytelling,

and its vivid, marginalised characters.

His first novel, Union Atlantic,

has already attracted comparisons

with the likes of Tom Wolfe and

Claire Messud, and is another

eloquent demonstration of Haslett’s

storytelling gifts. Also evident are his

obvious talent for producing a complex

and beautifully drawn range of

protagonists and a keen eye for the

social mores of small-town America.

Haslett’s main challenge in turning

his talent to a full-length work lay

in retaining an overview of the task

at hand, and he says, ‘Writing a [short]

story I can read all of what I’ve written

thus far each morning when I sit

down to work. That’s impossible with

a novel – the challenge is to retain

as much of the material of the novel

as I can, at my mental fingertips,

over a number of years.’

Written over the year before the

economic collapse of 2009, and set in

2002, this is essentially a book about the

state of America in the months following

9/11, which also serves as an incredibly,

yet unintentionally prescient prediction

of the current worldwide economic

predicament. Of this near-clairvoyant

aspect of the book, Haslett says: ‘I

did definitely want to explore the

psychology of power in finance. I just

had no idea it would end up being quite

so topical. That was never my intent.’

The key players in the novel are Doug

Fanning, an executive with the fictional

Union Atlantic conglomerate; Charlotte,

a retired school teacher and neighbour

to Doug’s huge status-supporting

mansion in rural New England; Henry,

Charlotte’s brother and a leader in a

federal regulatory agency; and Nate,

a high-school student who is Charlotte’s

tutee and eventually Doug’s lover.

The book skilfully weaves together the

narrative strands of a near-fatal financial

crisis for the eponymous Union Atlantic

and a legal bid by Charlotte to rid the

town of Finden of Doug’s newly built

mansion. These stories are also

bracketed by two shorter episodes,

one during the first Gulf War, and the

second playing out as the US begins the

invasion of Iraq. The main characters

and stories successfully capture the

sense of deterioration and despair

that slowly engulfed America in the

wake of 9/11, while the framing device

sets those stories in the context of an

America seeming to be constantly at

war: ‘Doug couldn’t sleep for watching

the stuff… Watching the endless

repetition of facts and speculation

and probable lies, the consumption

of which at least partially numbed

the helplessness of seeing it unfold

at such distance and so inexorably.’

The diametric opposition of Doug

Fanning, a quintessentially conservative

alpha-male and war veteran, driven by

a seemingly insatiable hunger for power

and money, and Charlotte Graves, the

nature-loving, left-wing dreamer, with

a passion for culture and nature, is

arguably the key driving force of the

novel, but should not be read as some

sort of social allegory, says Haslett:

‘I always begin and hopefully remain

concentrated on character in my

work, and thus while Charlotte may

indeed profess the liberal humanist

values and Doug profess the more

unfettered capitalist ones, they are

both people driven by their past and

present conditions as humans and

thus attached to their ideas with more

than rational conviction. I’m not so

much interested in pontificating on the

larger social stuff as I am in throwing

these people at each other.’

Indeed, the characters are perhaps

the most memorable aspect of Union

Atlantic, and they shine on every page,

along with a superb ear for natural

dialogue that contributes hugely to

the book’s overall sense of assurance

and veracity. Conversely, there are

one or two clunkier elements to the

book. Doug’s 20 years of self-imposed

exile from his mother, for example,

are never really fully explained,

and Charlotte’s brother happening

to be head of the New York Federal

Reserve might stretch the limits of

narrative credibility a touch.

That said, this is an undeniably

impressive debut, and there is more

to come, with a new novel already in

development, although details are

understandably sketchy: ‘It’s a long

process and it would be hard to say

with much accuracy at this point what

the book will look like. When you finish

a book, it’s a bit as if your larder is

bare and it has to be filled with new

ideas and fragments before you can

even think about preparing a meal.’

Whatever the recipe, I look forward to

tasting the finished dish. Adam Haslett

is undoubtedly a writer to watch. ¶

words greg e den pho tography frank w o ckenfels

corbisoutline](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apasimoncampbellwbq-12881070165048-phpapp01/85/Books-Quarterly-magazine-11-320.jpg)