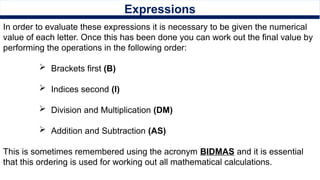

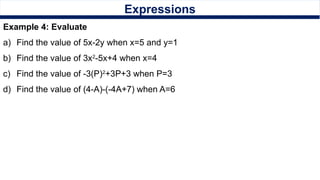

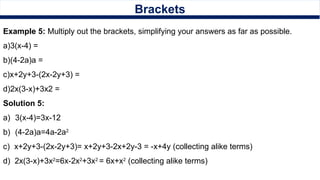

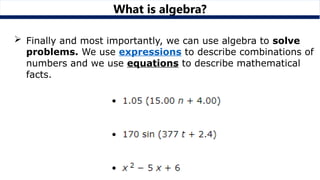

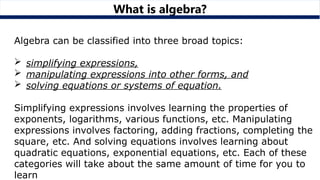

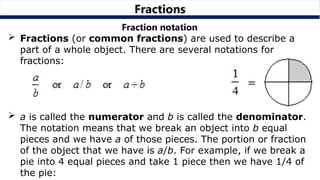

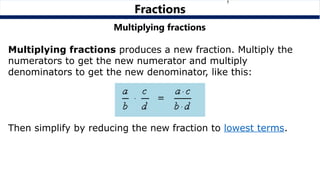

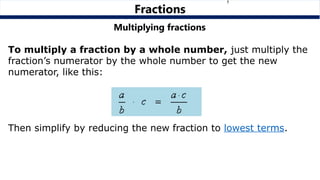

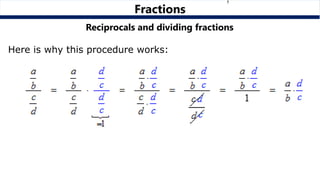

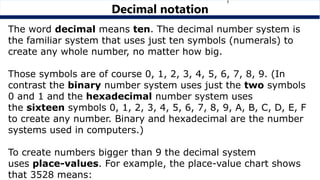

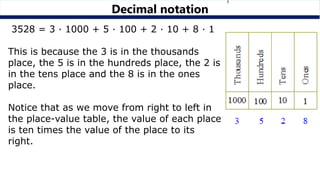

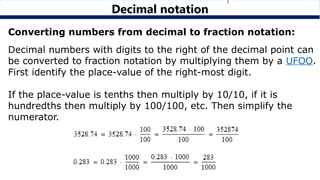

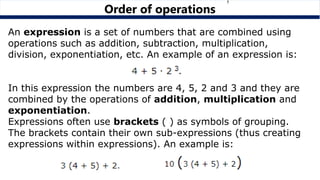

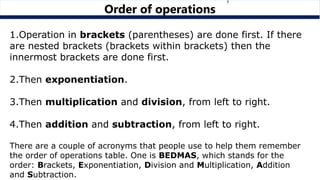

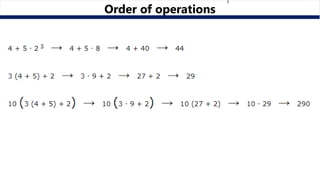

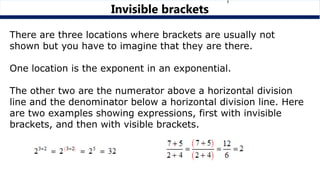

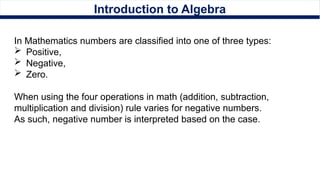

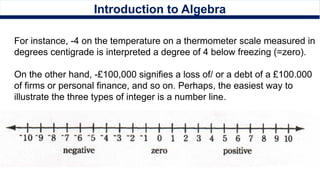

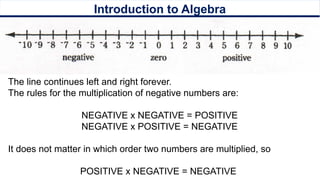

The document provides an introduction to algebra, explaining its functions, including representing numbers with letters, solving equations, and brief expressions. Topics covered include factoring, greatest common factor, lowest common multiple, and operations with fractions. It also describes decimal and exponential notations and outlines the order of operations in mathematical expressions.

![Introduction to Algebra

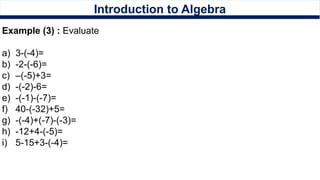

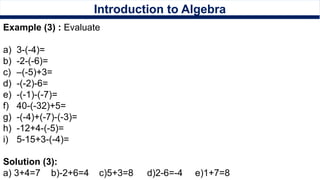

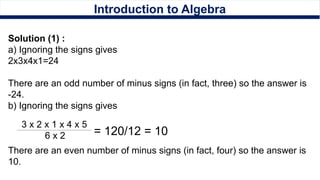

Practice Problem (1): Evaluate

a) 5 x (-6) =

b) (-1) x (-2) =

c) (-50) / 10 =

d) (-5) / (-1) =

e) 2 x (-1) x (-3) x 6 =

f) [ 2 x (-1) x (-3) x 6 ] / [ (-2) x (3) x 6 ] =](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01-241017111337-c01d9106/85/basic-mathematics-for-bussiness-01-pptx-58-320.jpg)