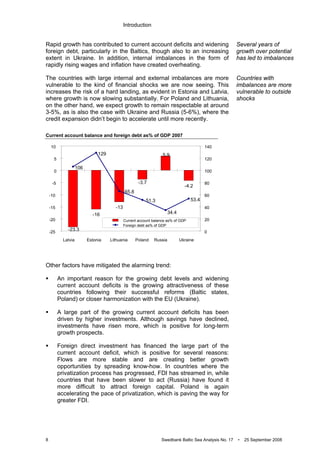

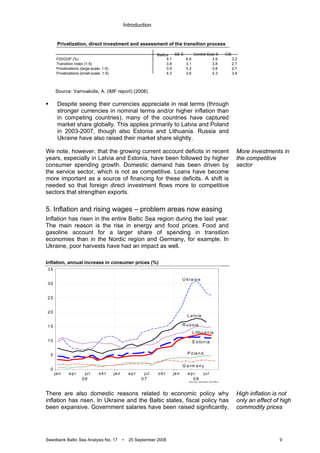

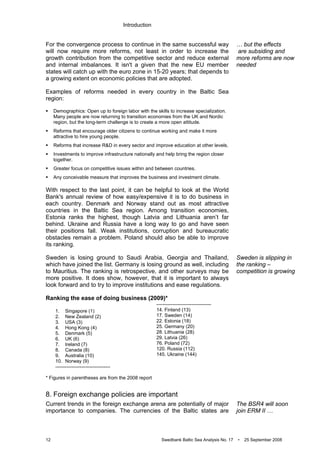

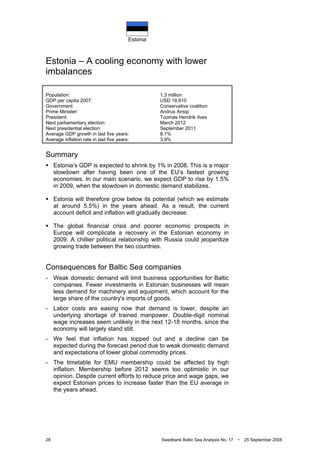

The Swedbank Baltic Sea Report outlines a significant slowdown in economic growth for the Baltic Sea region, expecting GDP growth of 2.2% in 2008 and 1.4% in 2009, largely due to the global financial crisis. Although some countries like Russia and Ukraine are showing stronger domestic demand, others like Estonia and Latvia are experiencing declines in economic activity. Reforms are needed across the region to improve the business environment and support growth despite these challenges.