This book provides a complete guide for high school athletes to maximize their opportunities to earn an athletic scholarship and achieve their full potential. It includes advice from many former college coaches, athletes, and experts on navigating the complex recruiting process. The endorsements praise the book for breaking down the tangible and intangible aspects of recruiting in a straightforward way and serving as an invaluable resource for both athletes and their parents.

![THE HOW TO GUIDE DURING HIGH SCHOOL 191

S a mpl e S c r i p t

Student-athlete: Hi. My name is Jane Student. I’m a soccer player at Boulder High

School in Boulder, Colorado. I received your questionnaire last week. Thanks

for sending it. I sent it back a few days ago, and I’m really interested in your

program. I’m wondering if you have a few minutes to answer some of my

questions.

What GPA and ACT or SAT would I need to have a chance to attend your school

and play for your program?

Have you had a chance to see me play? [If the student-athlete has not sent the

coach a highlight or skills video, replace this question with: Would you like me to

sendyoualinktomyvideo?]

When would be a good time to visit your campus?

How many players are you recruiting from my position?

Thanks so much for your time. I just have two more questions:

What else would I need to do to have a chance to compete for your program

and earn a scholarship?

What is the next step I should take with you?

Great! Do you have any questions for me?

[Pause to allow the coach to ask questions, which the student has prepared for in

advance,perpage192through196.]

I really appreciate your time, and I look forward to talking with you in the

future.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/awtext-101409-101110152635-phpapp02/85/Aw-text-101409-223-320.jpg)

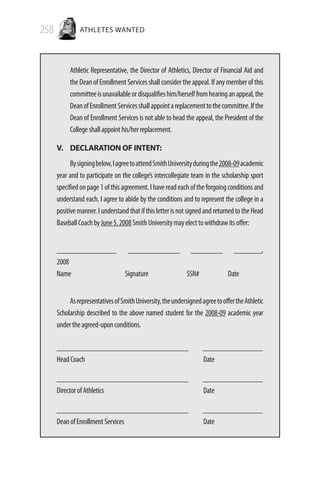

![226 ATHLETES WANTED

Justin Sherman

Grad Year Height/Weight Age GPA

2009 5’10” 17 3.53/4.0

Parents: Kelly and Lynn

ADDRESS:

1415 N. Dayton Street, Apt. 4

Chicago, IL 60622

Home Phone: (888) 333-6846

Mobile Phone: (555) 555-0000

Email: mgolf@ncsasports.org

SCHOLASTIC INFORMATION:

Belvidere North High School

Phone: (555) 555-1111

Enrollment: 2200

Overall GPA: 3.6/4.0

SAT[1600]: 1240

Math: 600

Reading: 640

Writing: 590

Honors Classes: Algebra, English

Desired Major: Undecided

Eligibility Center: Yes

ACADEMIC HONORS/AWARDS:

National Honor Society (2007-09)

ATHLETIC INFORMATION:

Four-time varsity letterman (golf, 2005-08)•

Third in state meet (70, 73) (2008)•

First-Team All-Conference (2008, 2007)•

First-Team All-District (2008)•

District Qualifier, Fifth Place (2008)•

Team Captain (2008)•

CLUBS/CAMPS:

AJGATournaments•

Sixth in Myrtle Beach Invitational (72, 71)•

Tenth in Chicago Jr. Invite (70)•

STATISTICAL DATA:

Home Course: Beckett Ridge Country Club

Course Par: 72

Course Slope: 136

Course Rating: 73.3

CourseYardage: 6857

08 AJGA

Handicap: 1.3

Nine-Hole Average: 37

Nine-Hole Low: 34

Eighteen-Hole Average: 73

Eighteen-Hole Low: 70

Average Drive: 295 yards

Driving Accuracy: 85 percent

Greens in Regulation: 14

Putts/18 Holes: 29

08 HIGH SCHOOL

Handicap: 0.1

Nine-Hole Average: 35

Nine-Hole Low: 32

Eighteen-Hole Average: 71

Eighteen-Hole Low: 68

Average Drive: 295 yards

Driving Accuracy: 90 percent

Greens in Regulation: 16

Putts/18 Holes: 26

SA M P L E r é s u m é](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/awtext-101409-101110152635-phpapp02/85/Aw-text-101409-258-320.jpg)