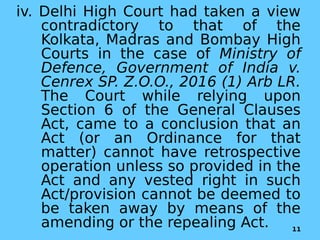

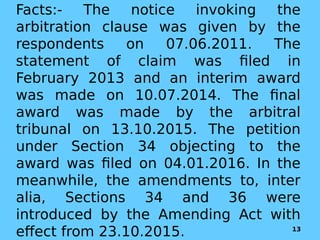

The document analyzes Section 26 of the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015, focusing on the ambiguity of whether it applies retrospectively or prospectively to pending arbitration cases. Various high court rulings on this matter illustrate differing interpretations regarding the applicability of the amendments to ongoing arbitration and related court proceedings. Ultimately, the document emphasizes that amendments affecting substantive rights cannot be applied retroactively unless explicitly stated, suggesting that existing rights under pre-amendment laws must be preserved.

![The Amendment Act, however,

puts an embargo on the use of the

wider ground of 'patent illegality'

against arbitral awards in

'international commercial

arbitrations' [Section 34 (2-A)],

and besides, it makes the right

under Section 34 more onerous by

the amputation of automatic

suspension of the enforcement of

the award, by adding Section

36(2) and 36 (3) of the New Act. 27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/arbitration-171001071812/85/Arbitration-and-Concilation-Amendment-Act-2015-27-320.jpg)

![The Amendment Act affecting an Accrued

Substantive Right:-

That the Amendment has placed a

restriction, or that it has had an impact on

the right under Section 34 which cannot be

disputed.

The question, therefore, is whether such a

restriction or burden can be imposed on the

right to seeking setting aside an award

(arising from pre-Amendment arbitral

proceedings). That would not be the case,

going by the ratio laid down by the Judicial

Committee in Colonial Sugar Refining Co.

Ltd. v. Irving [1905 A.C. 369 (U.K.)] which

stated that any interference with the existing

rights is contrary to the well-known principle

that statutes are not to be held to act

retrospectively, unless a clear intention to

that effect is manifested. 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/arbitration-171001071812/85/Arbitration-and-Concilation-Amendment-Act-2015-28-320.jpg)