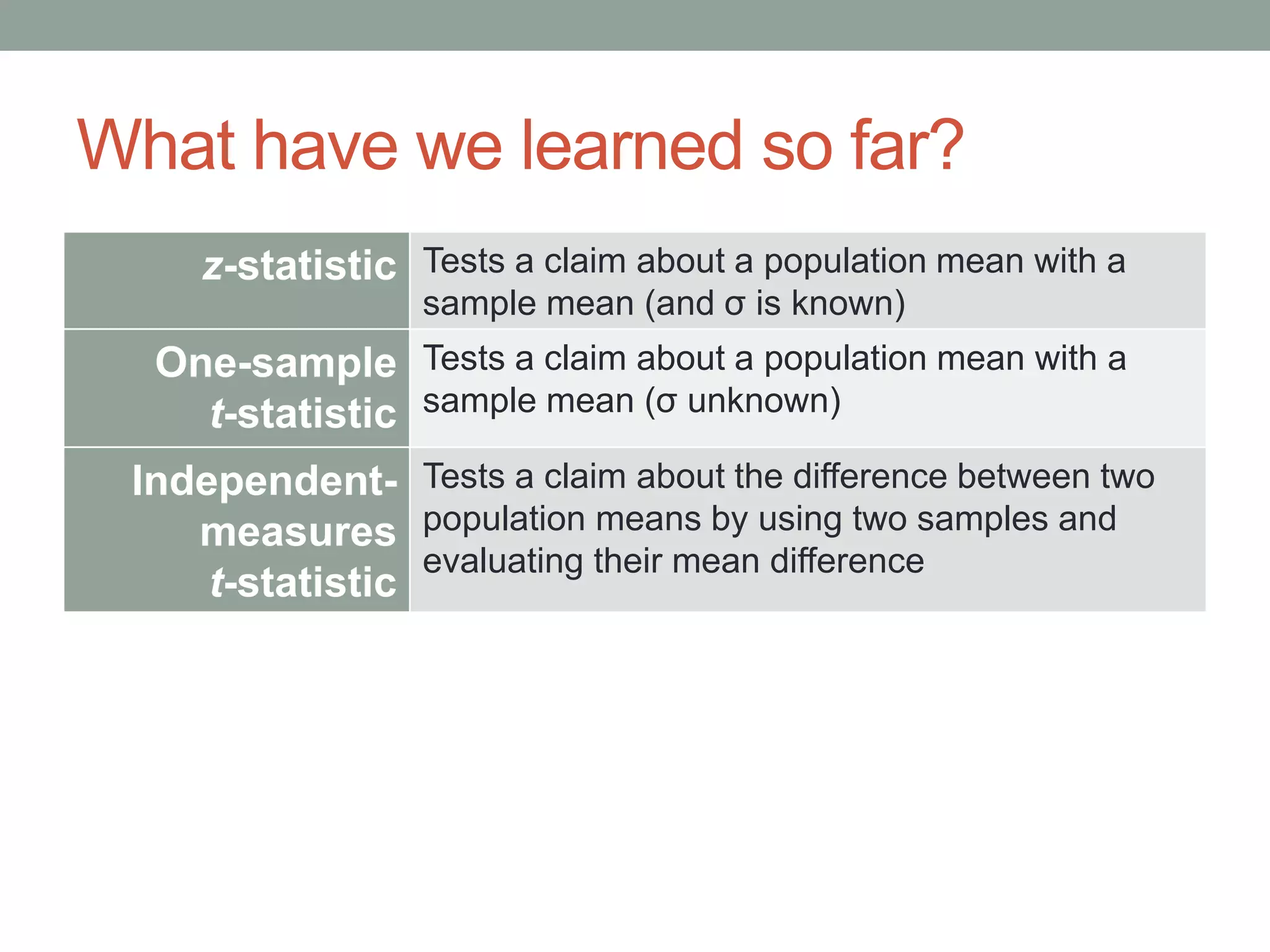

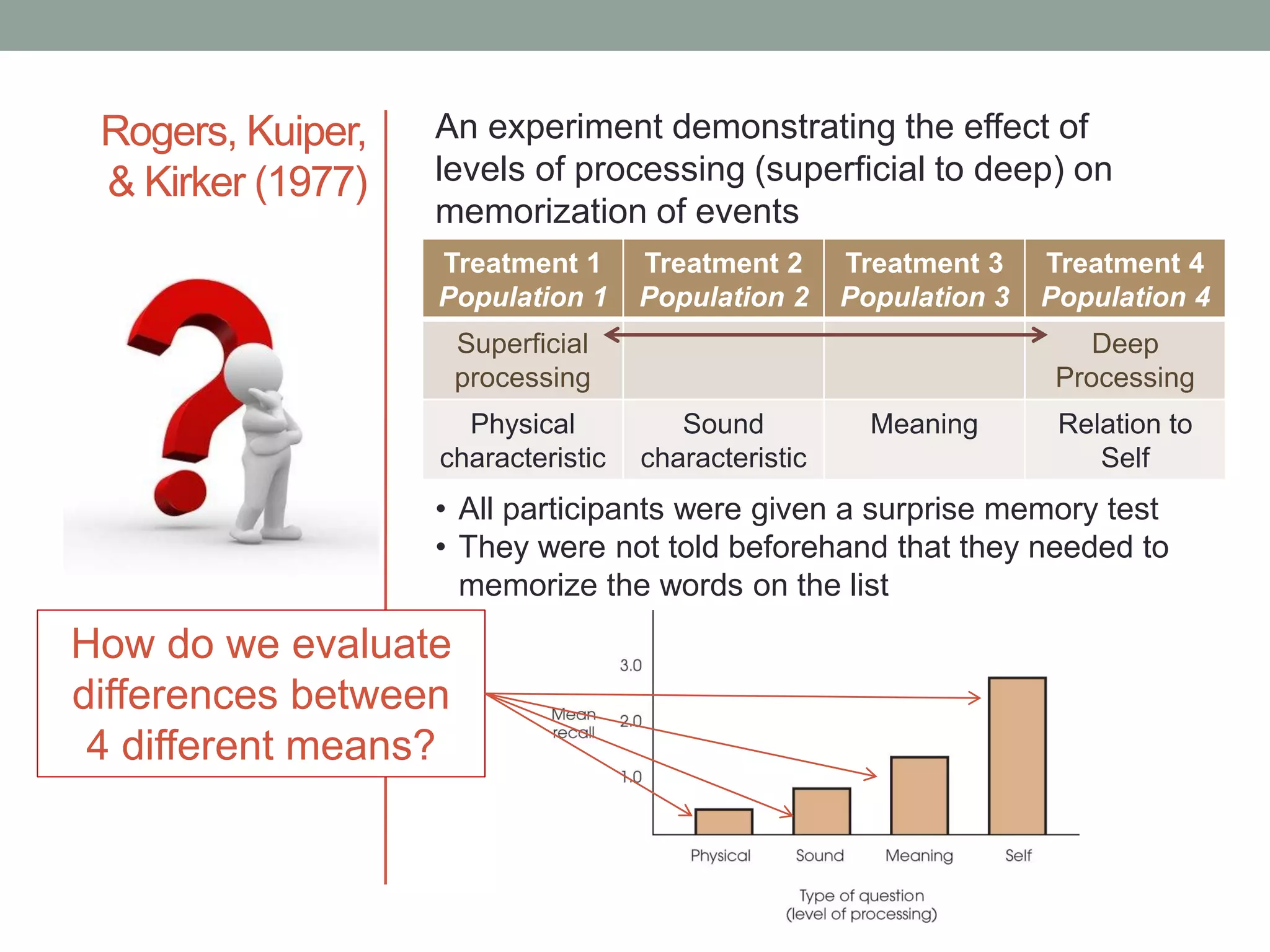

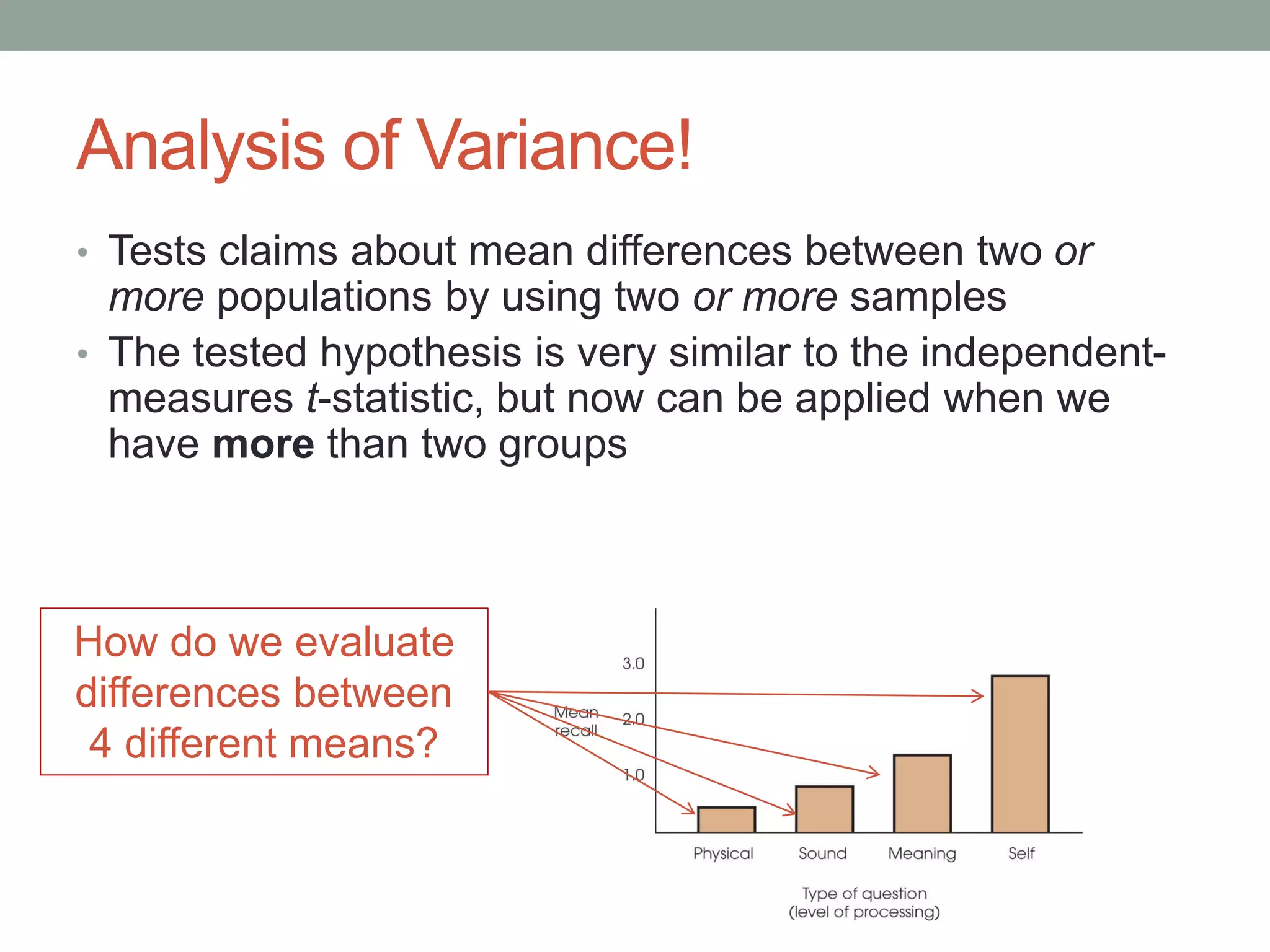

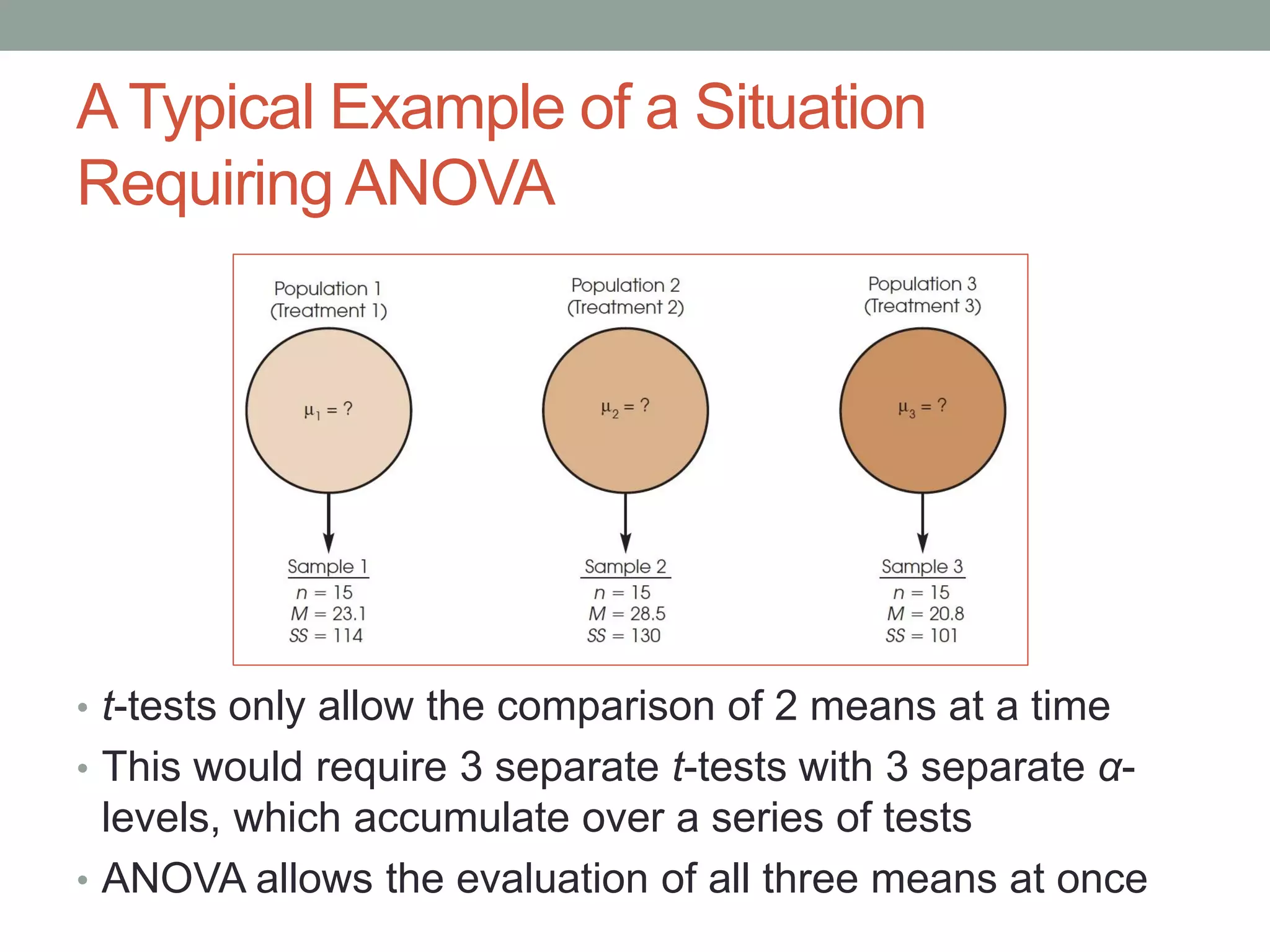

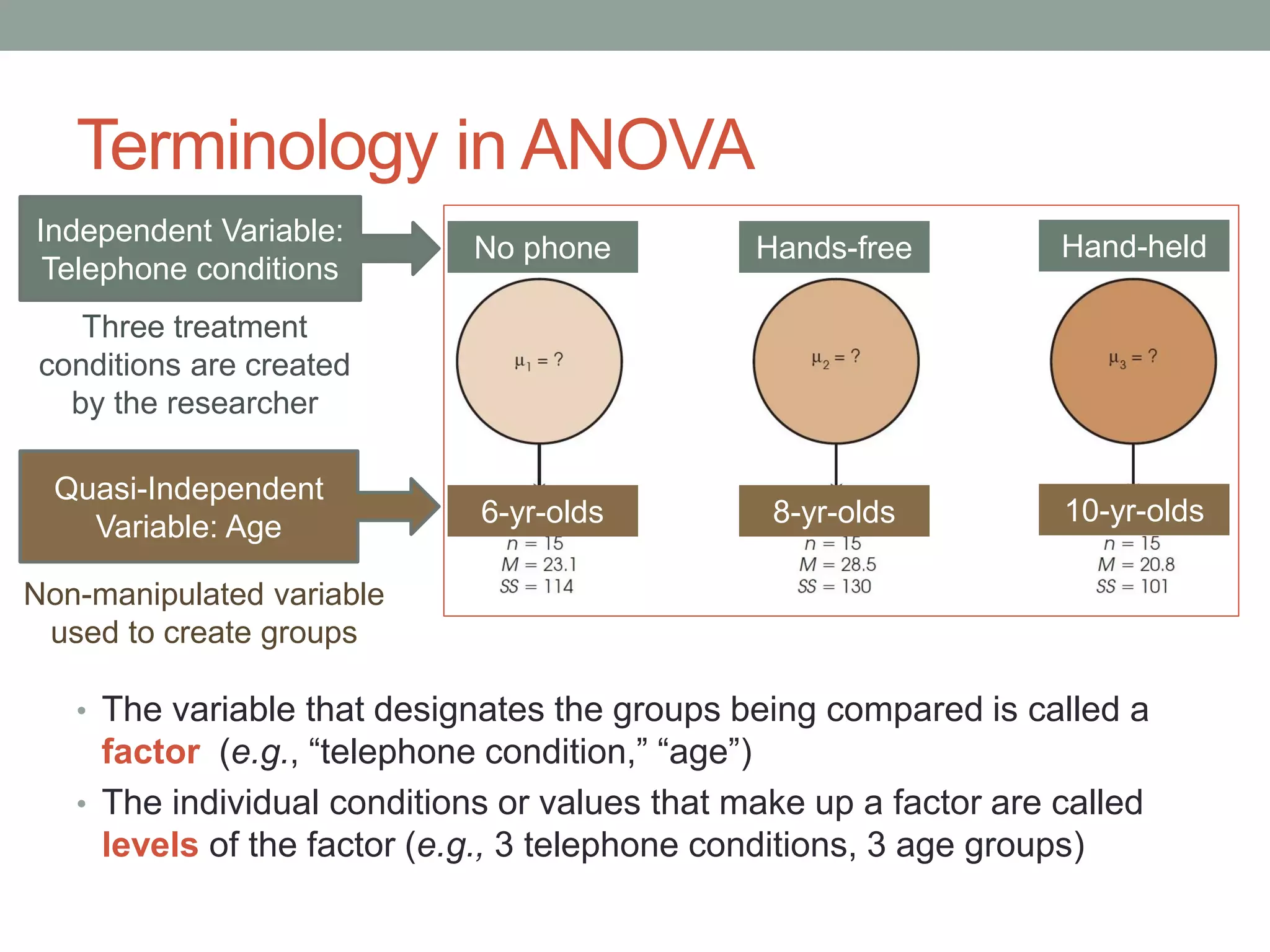

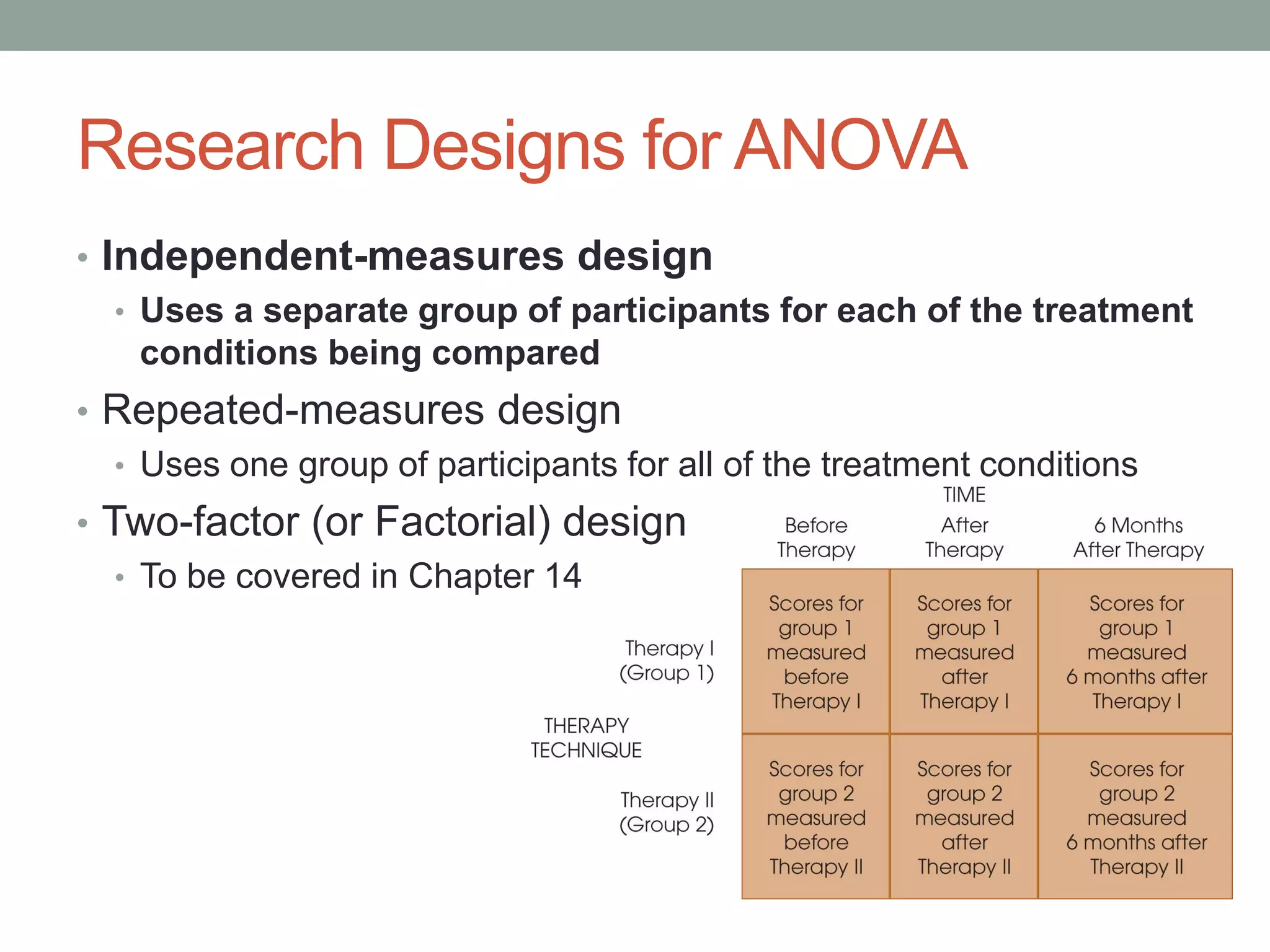

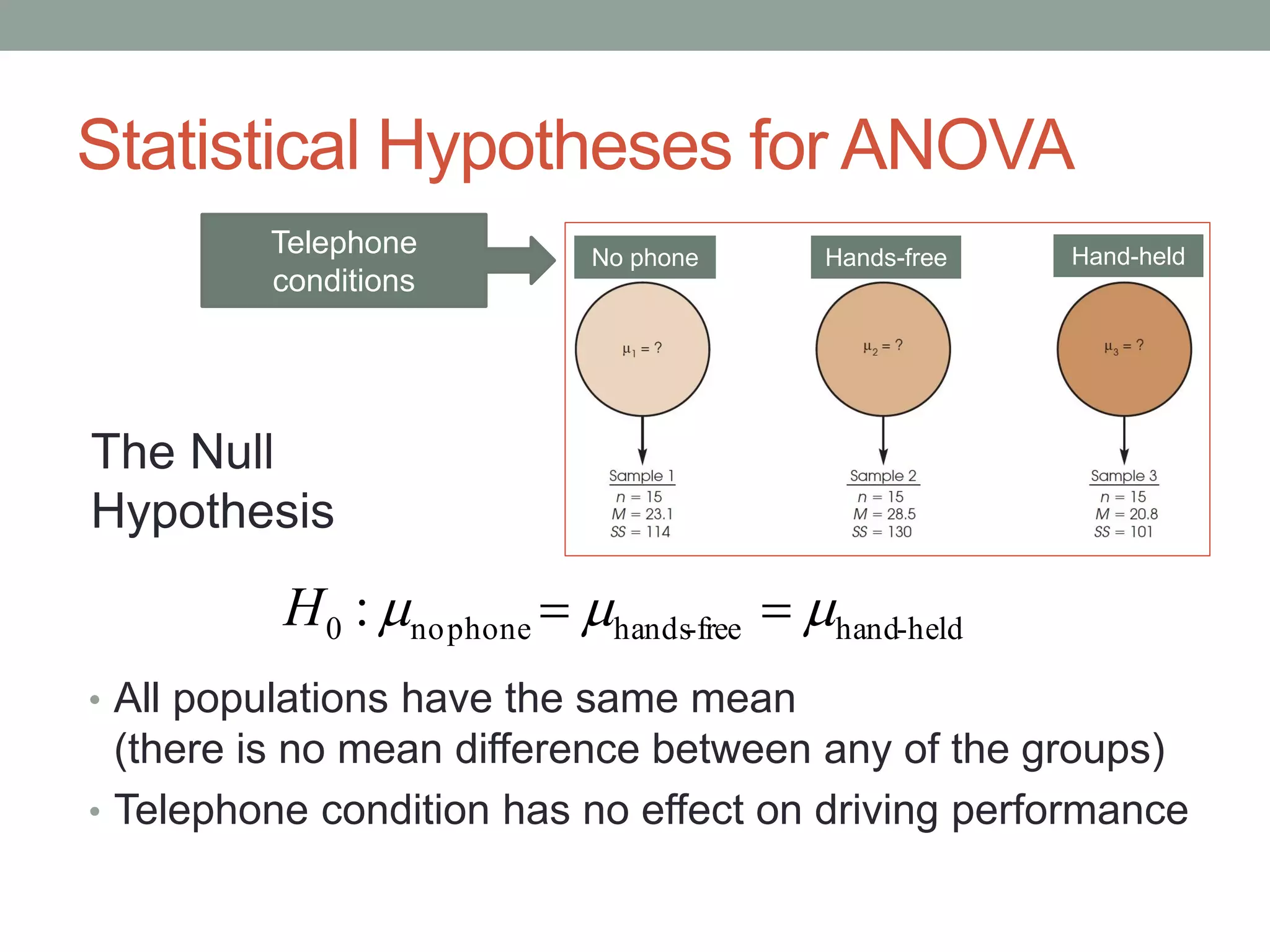

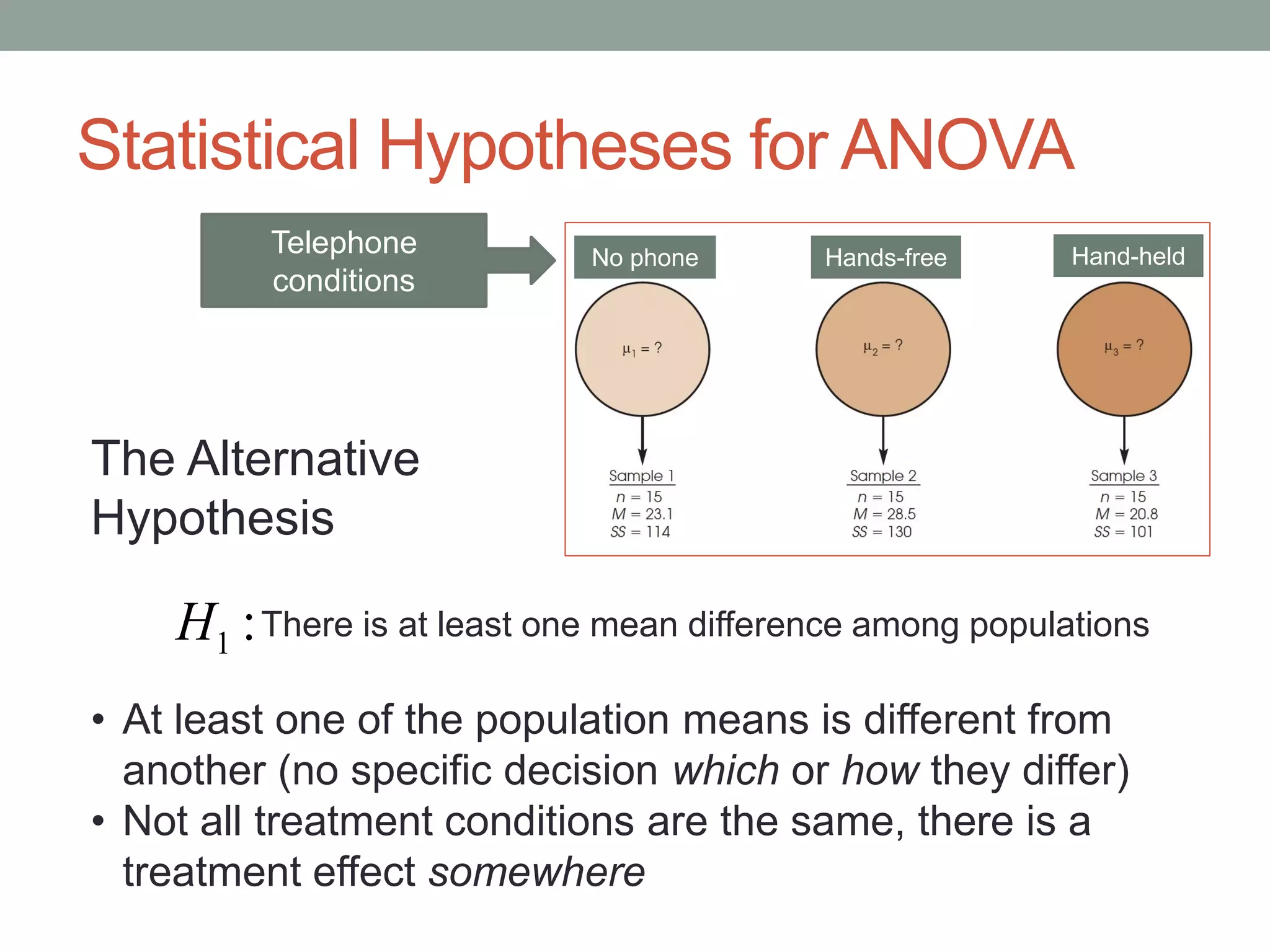

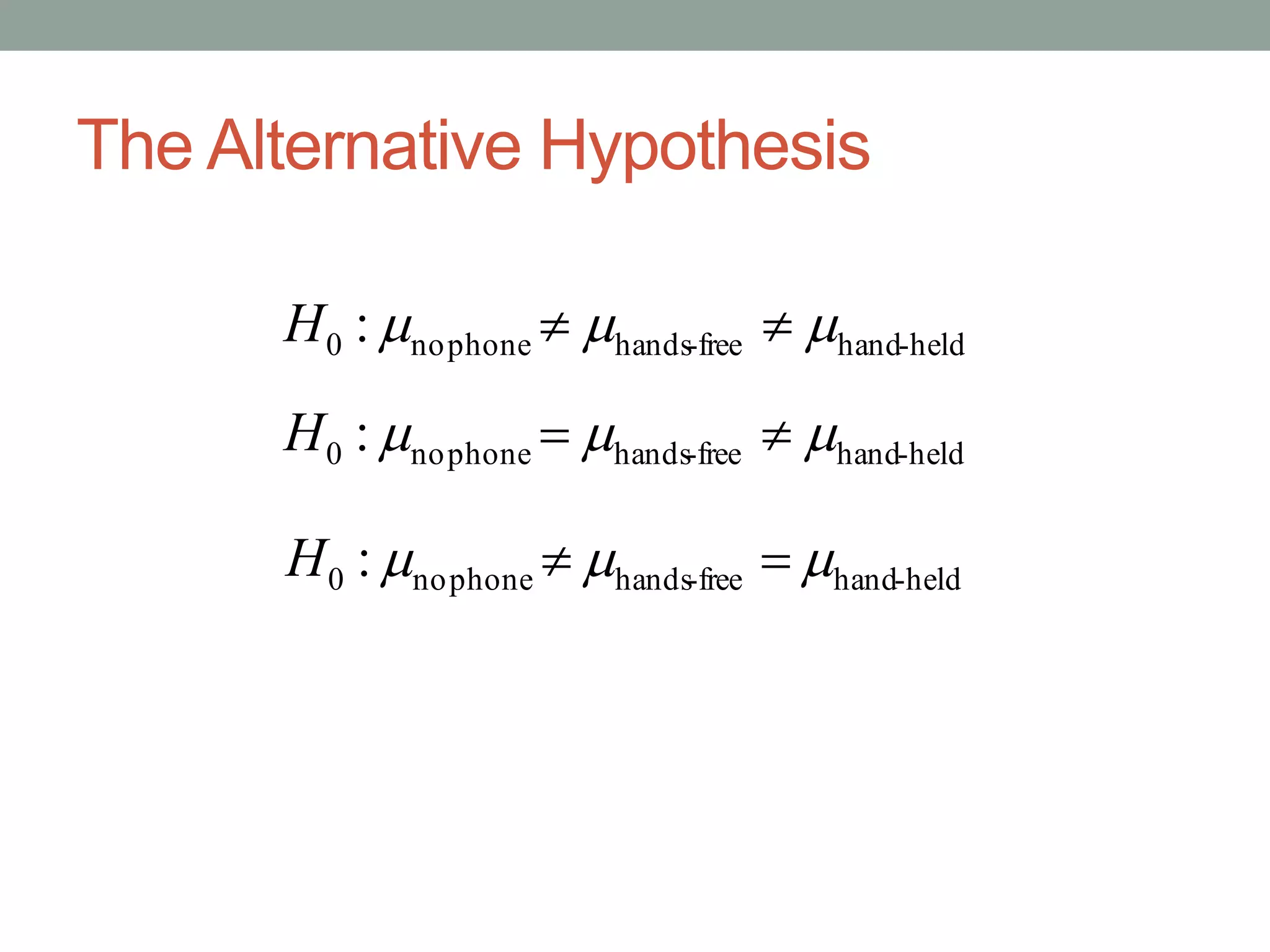

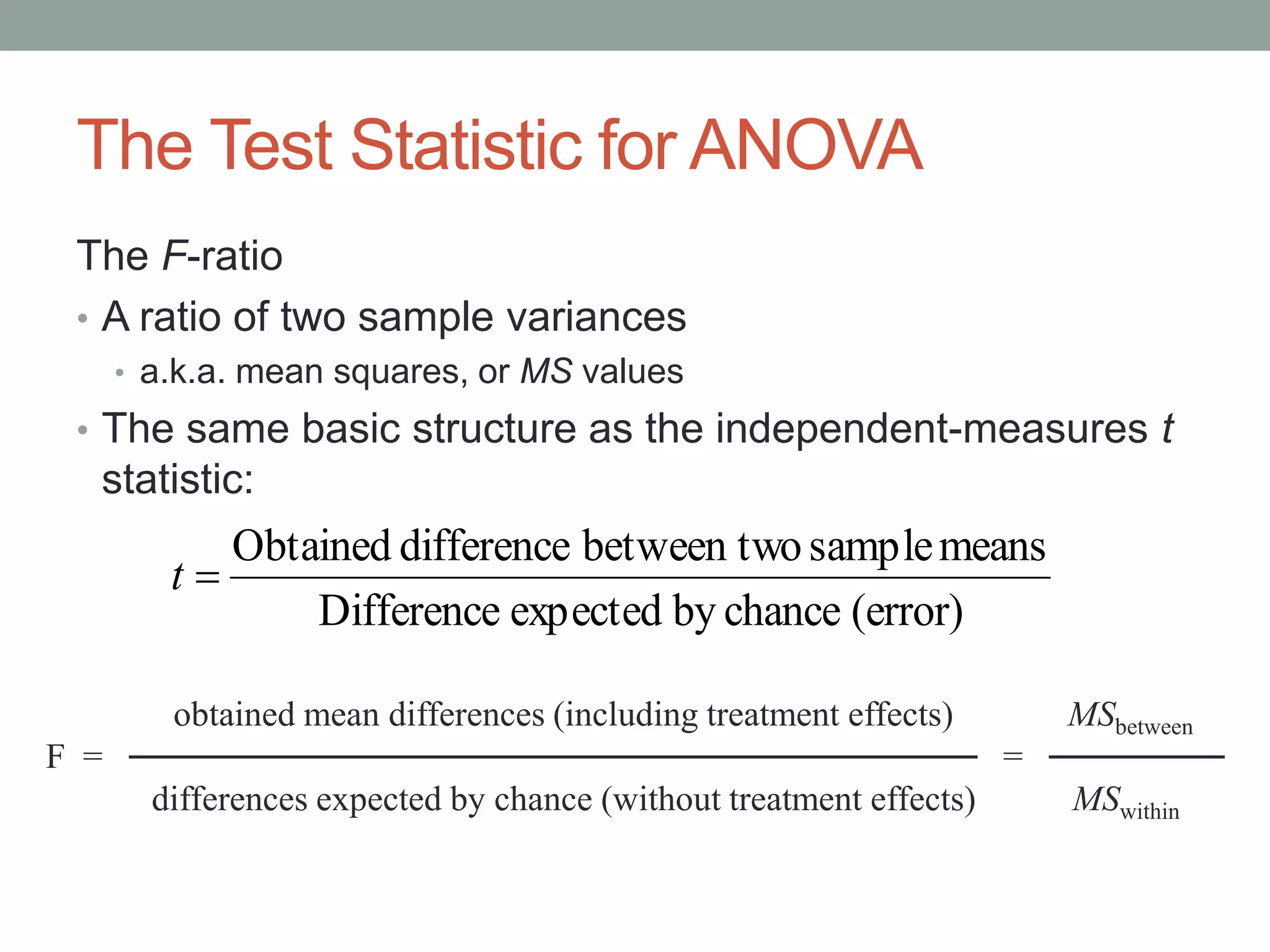

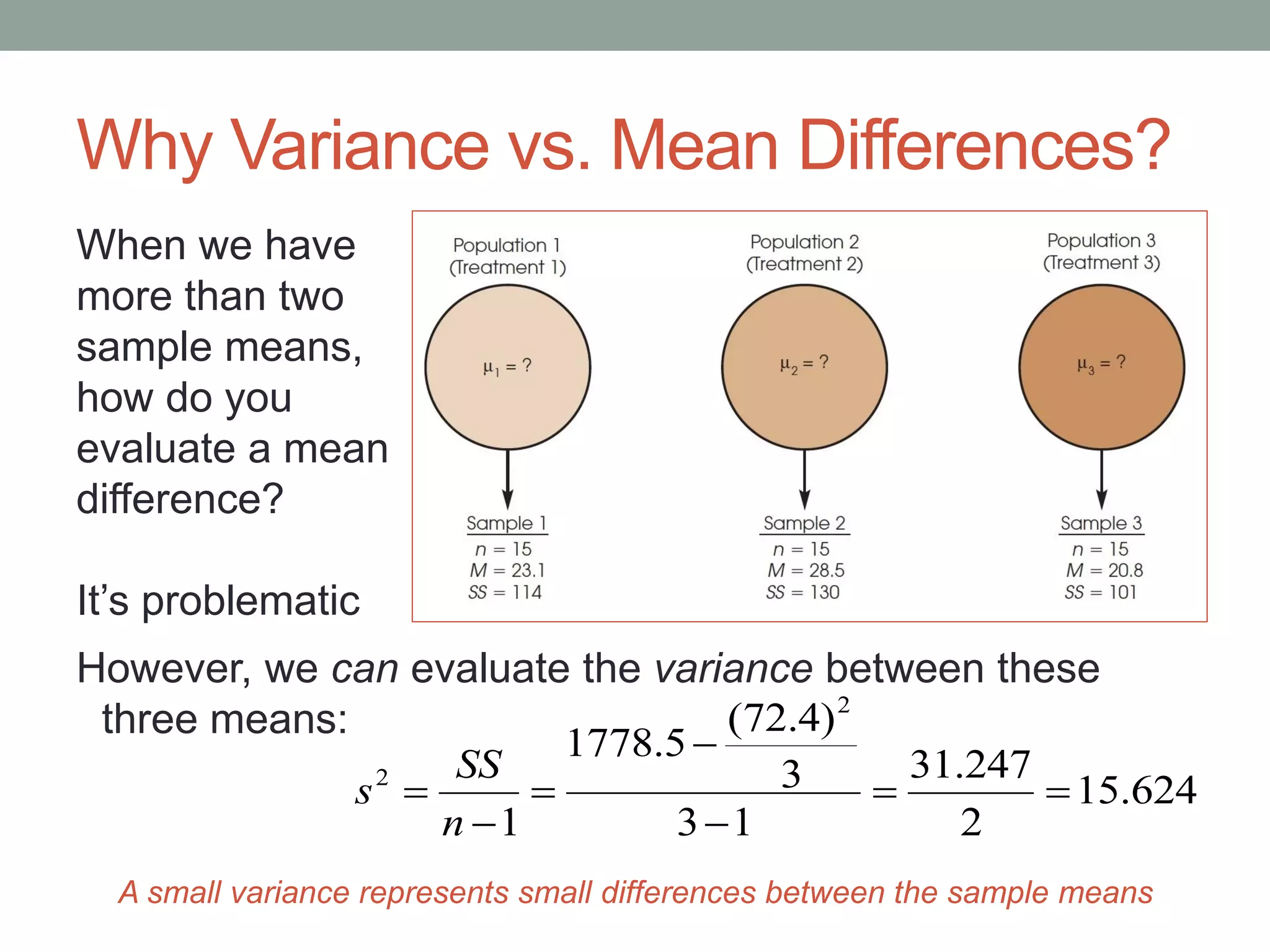

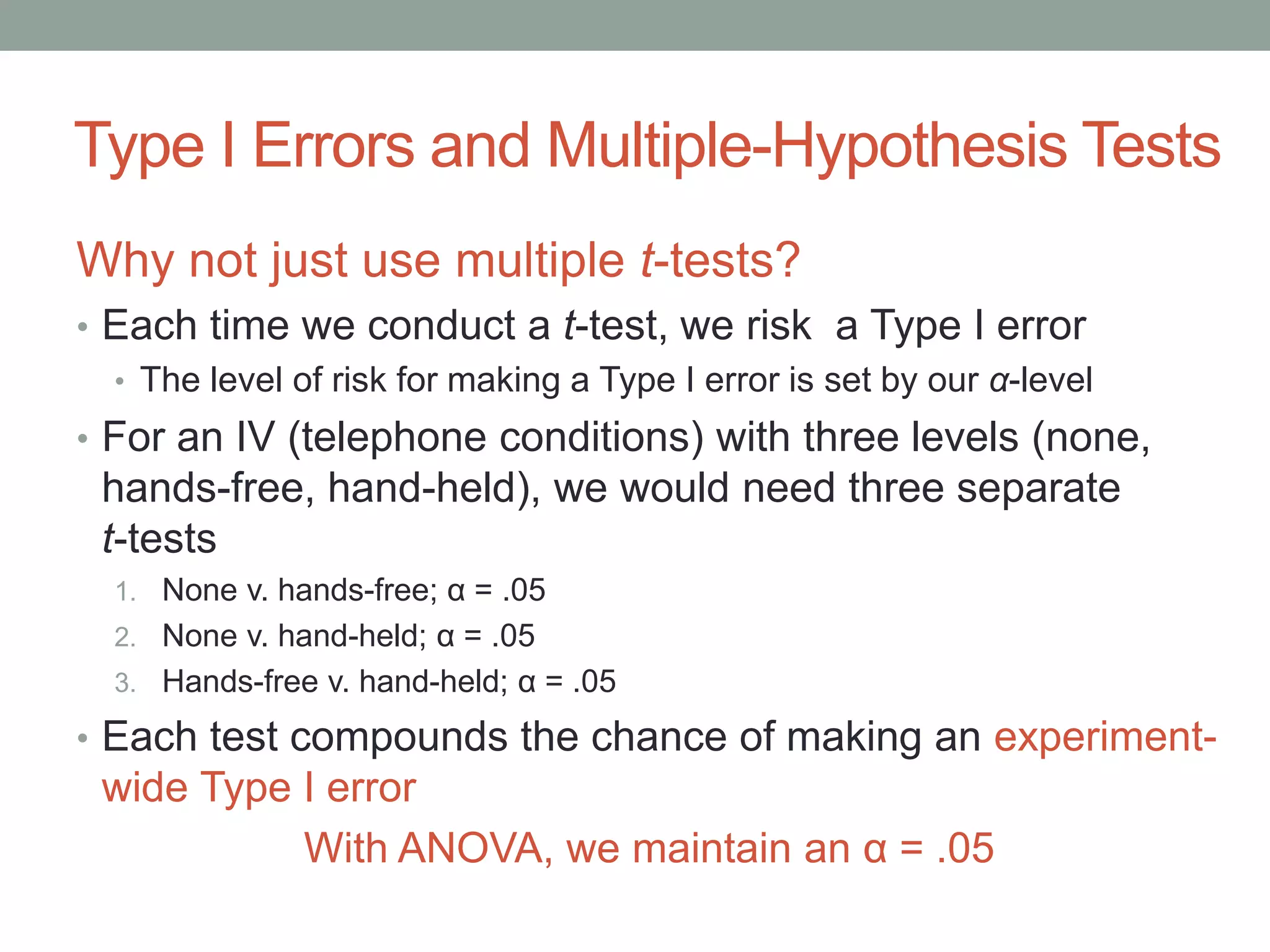

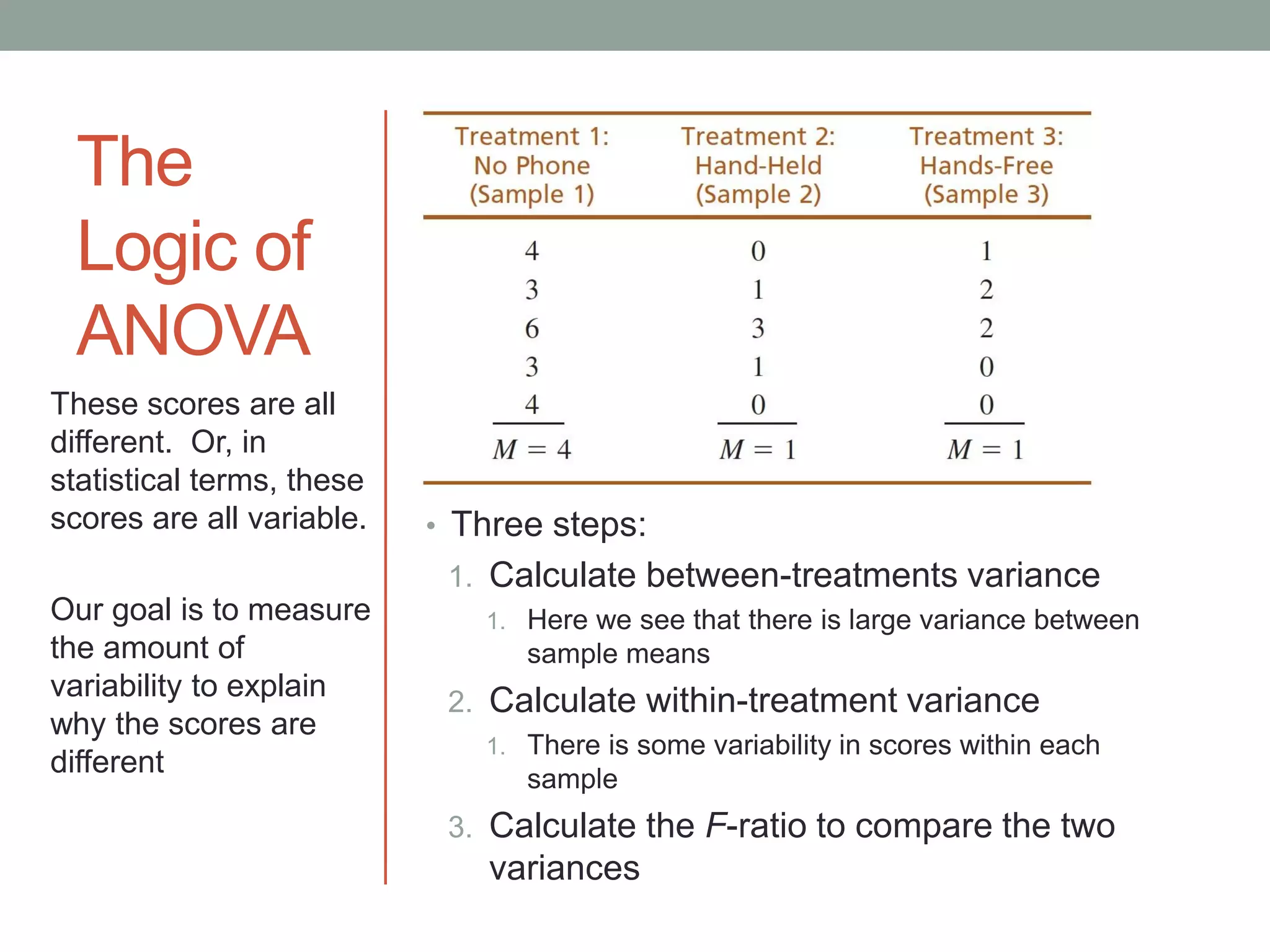

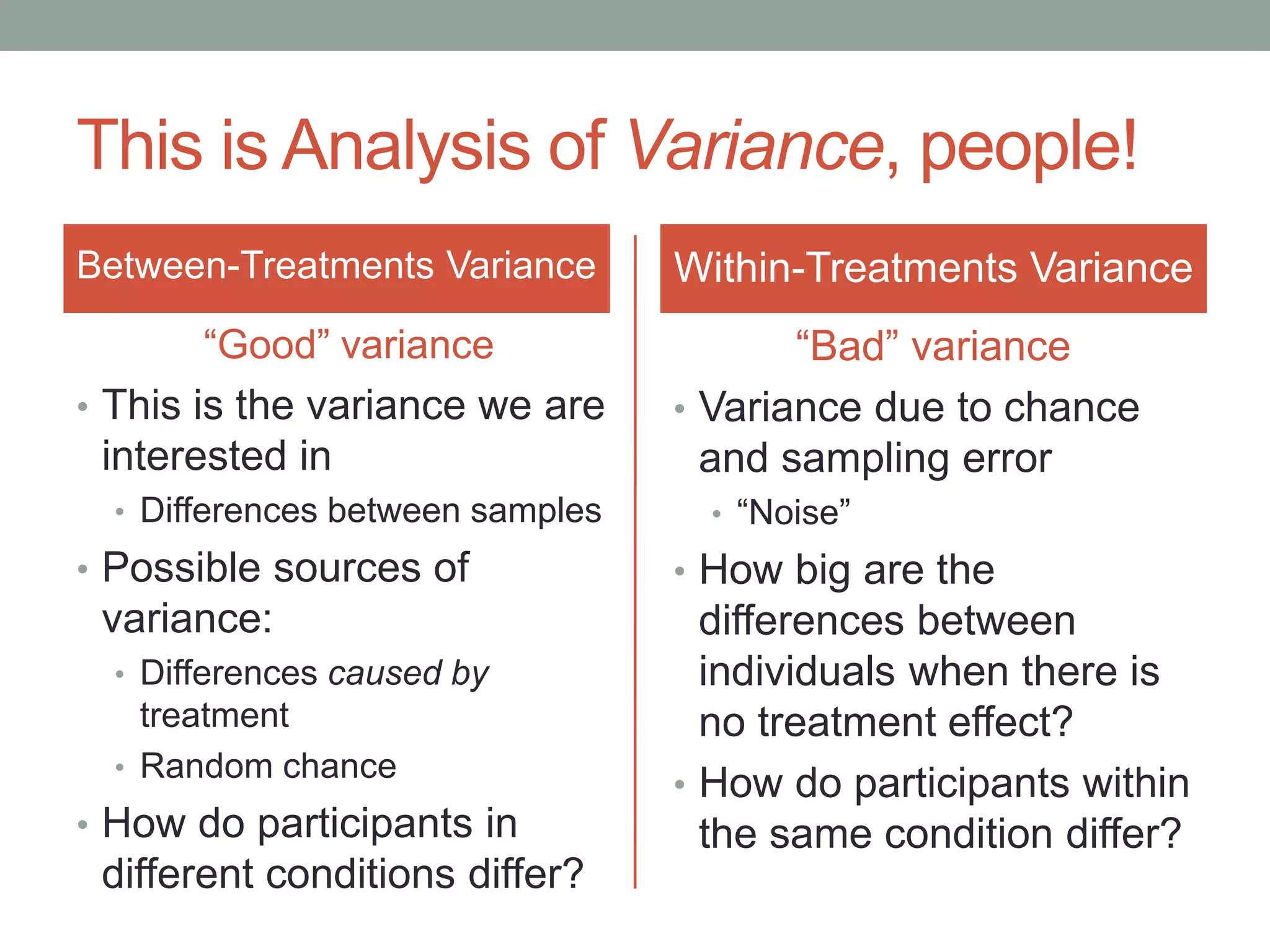

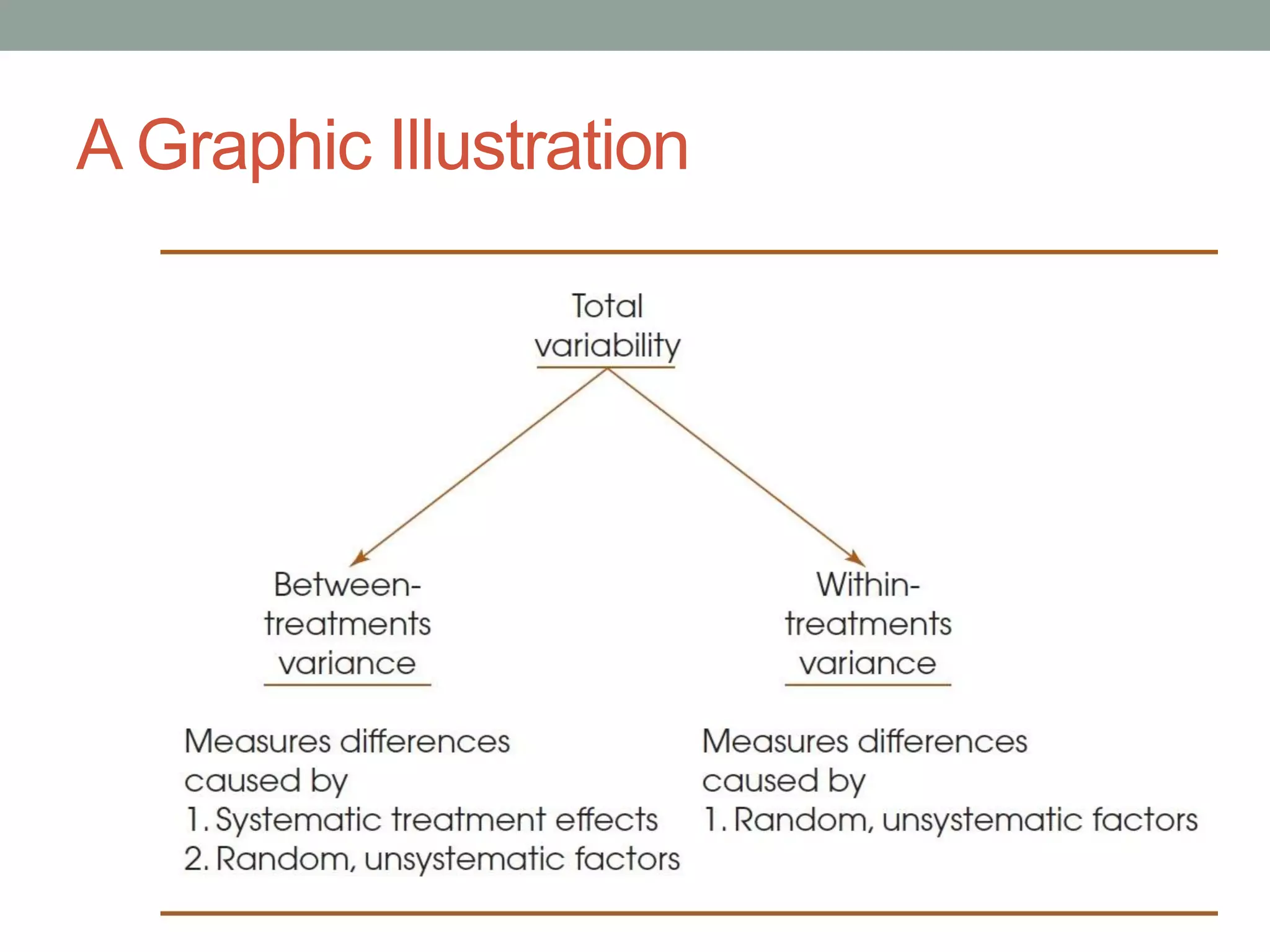

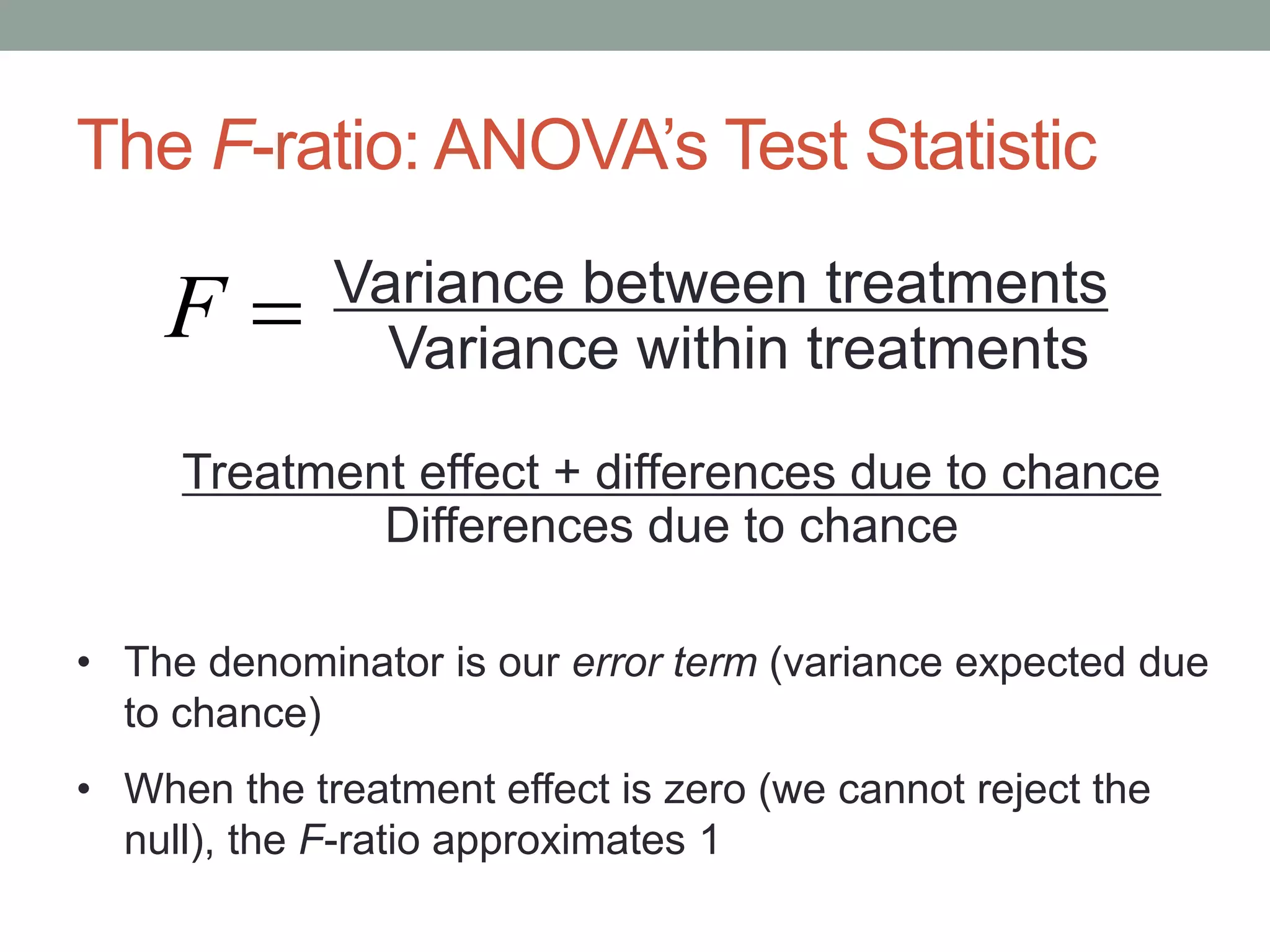

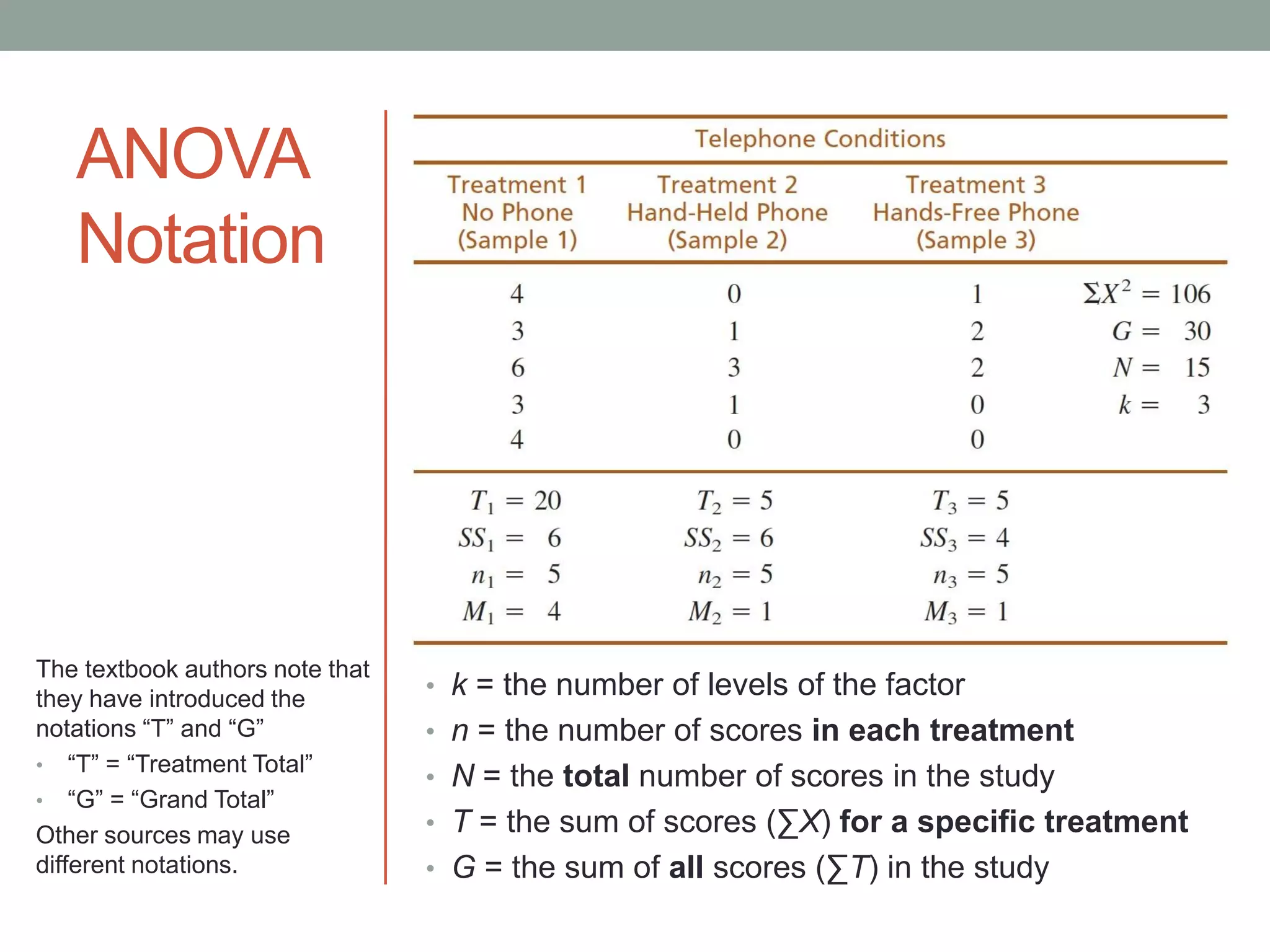

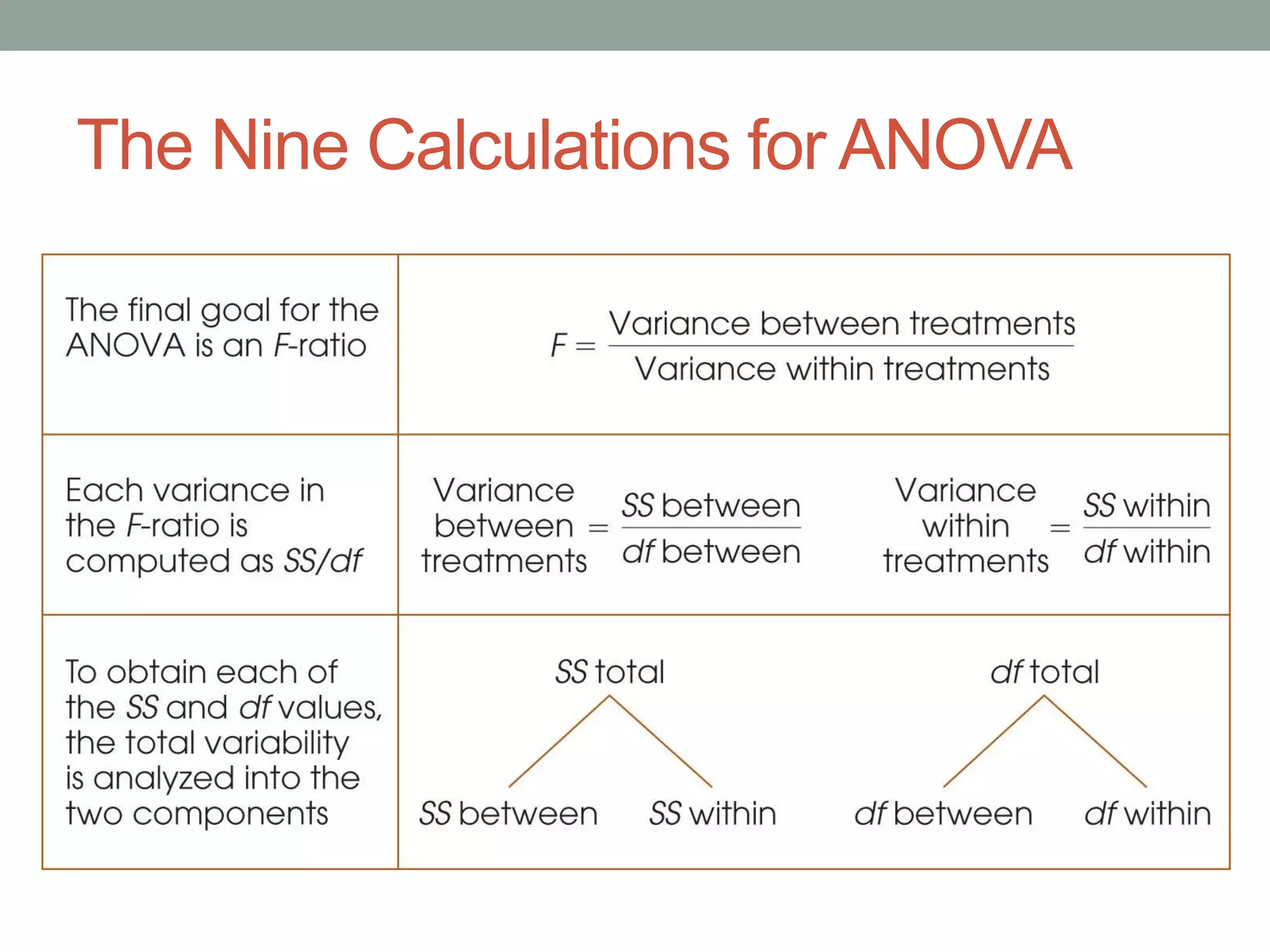

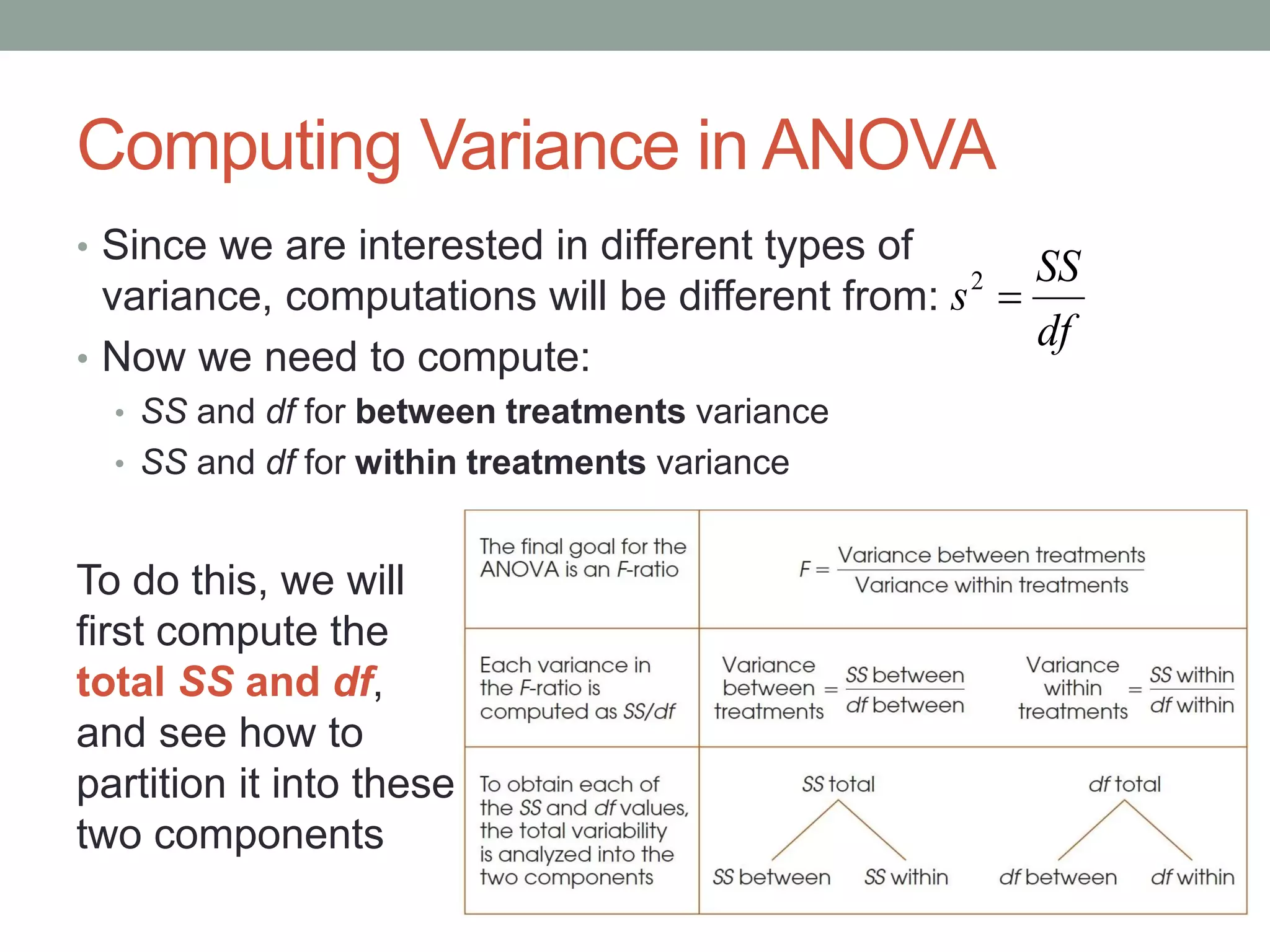

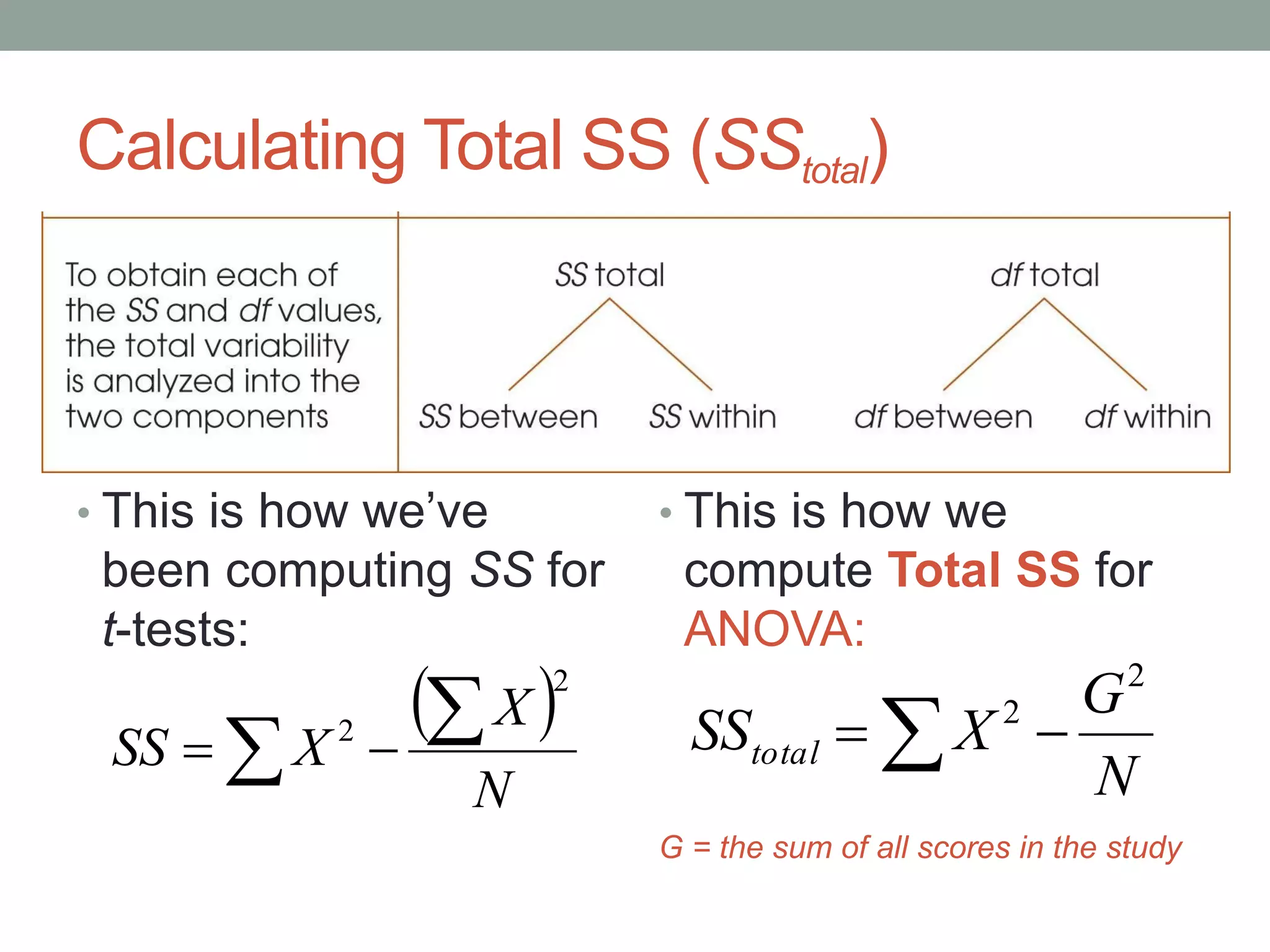

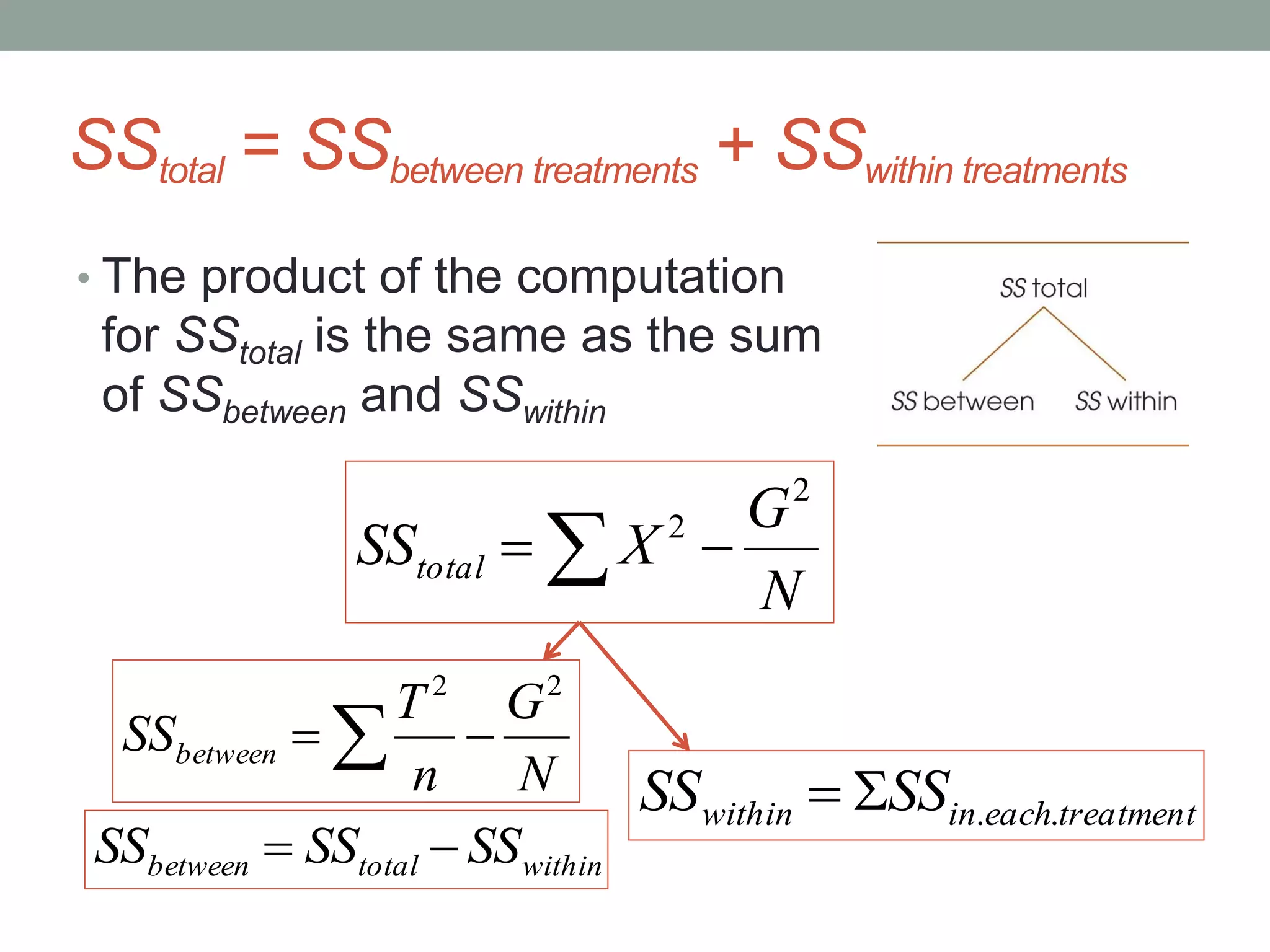

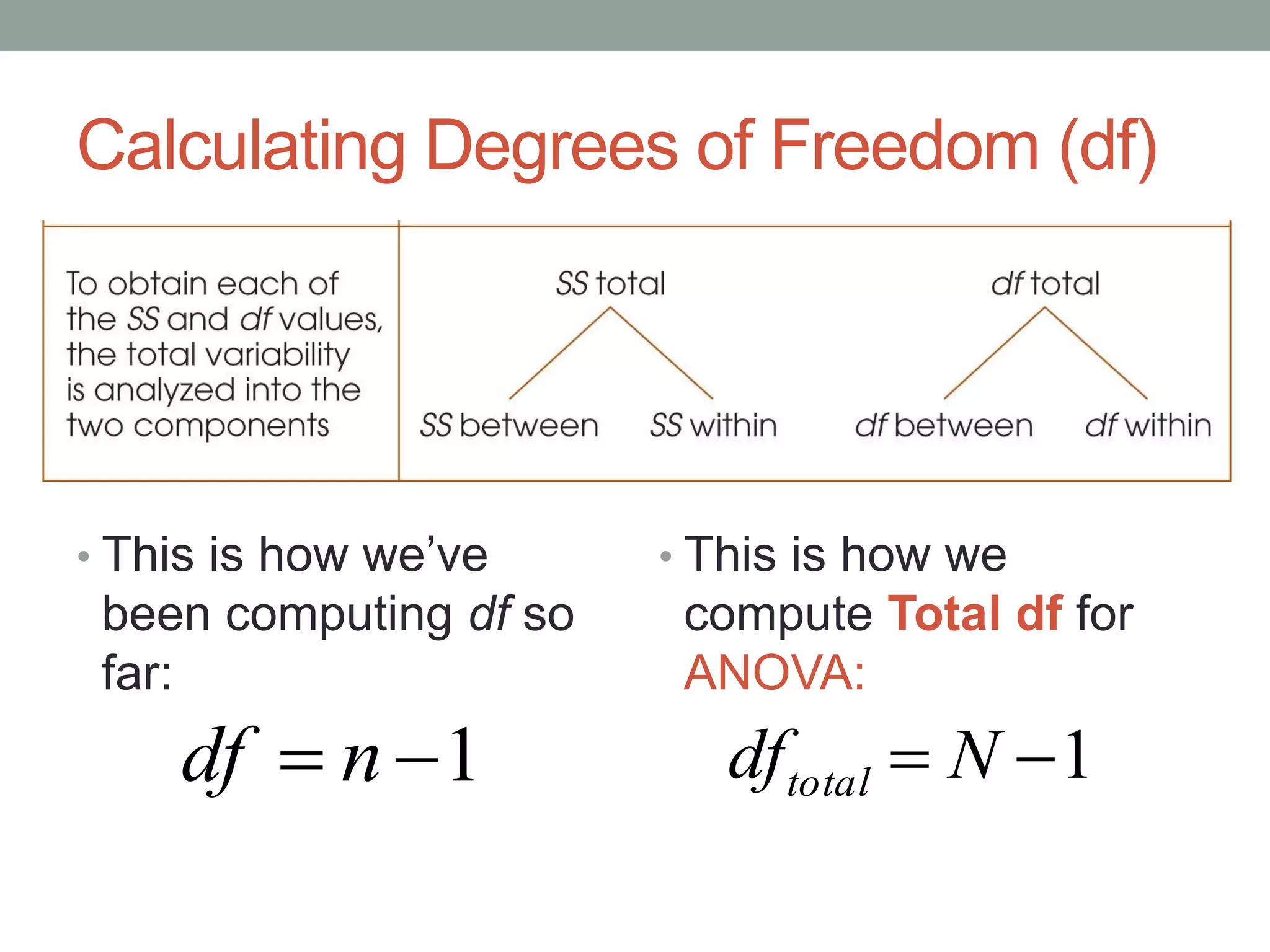

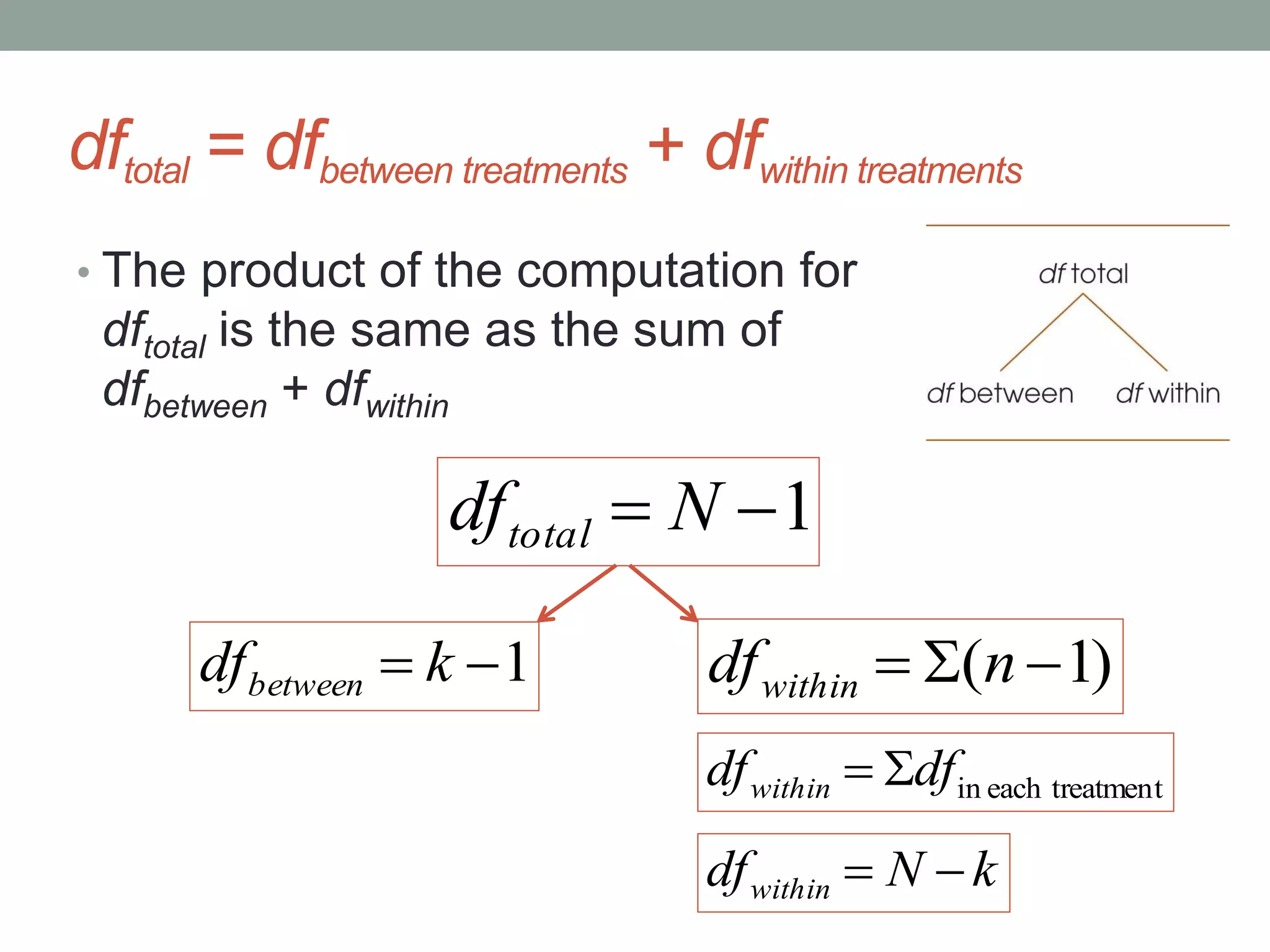

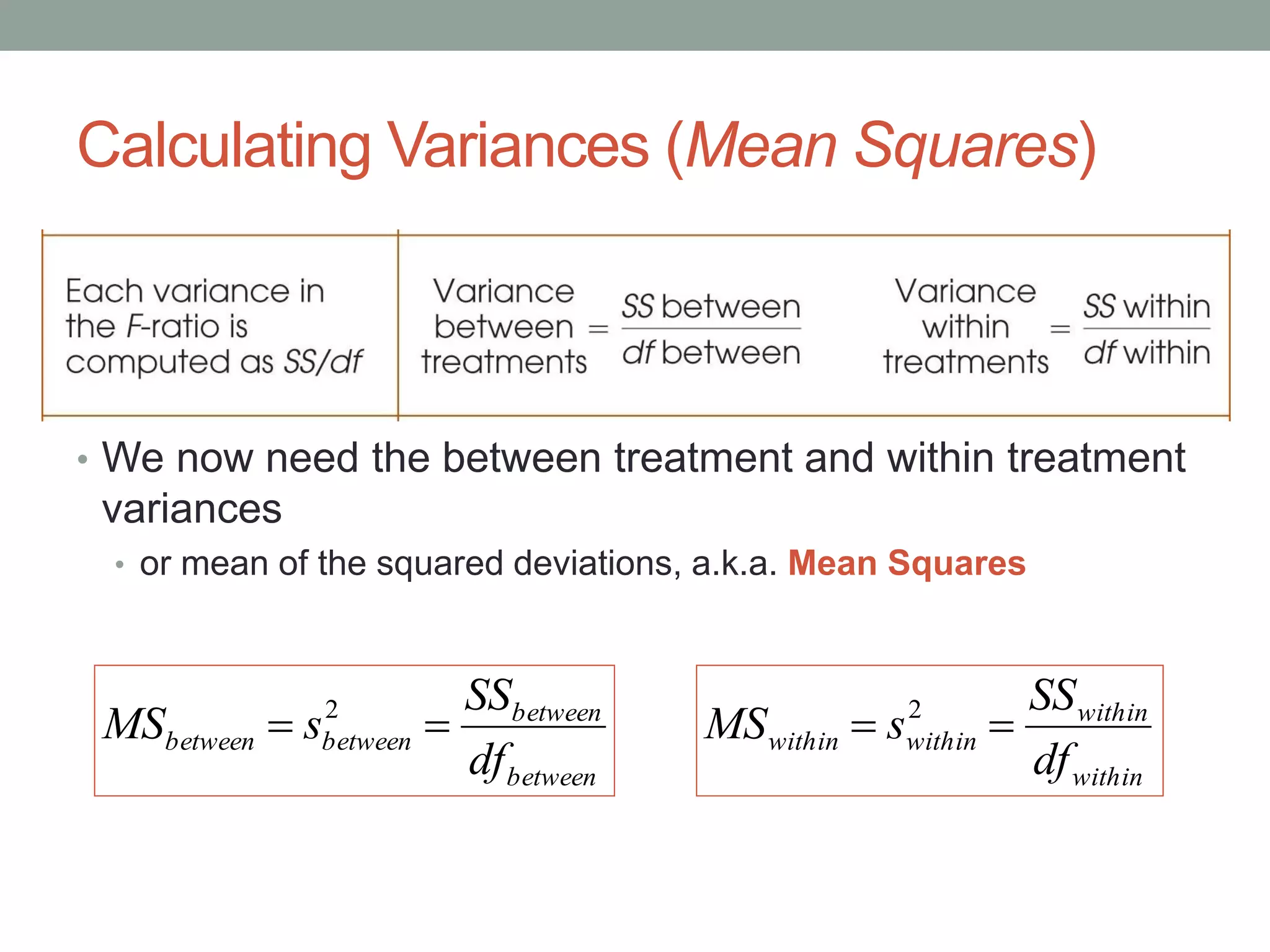

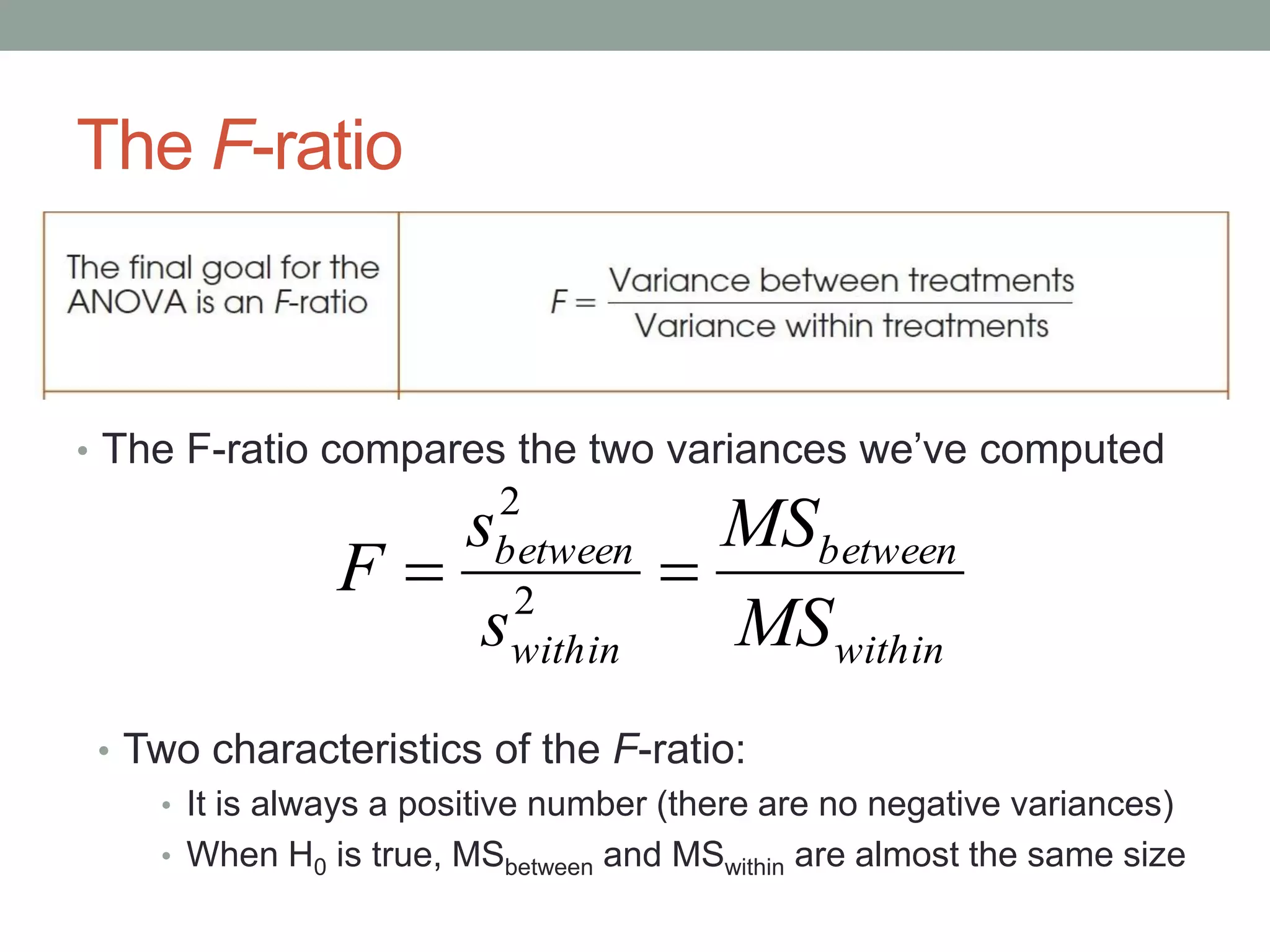

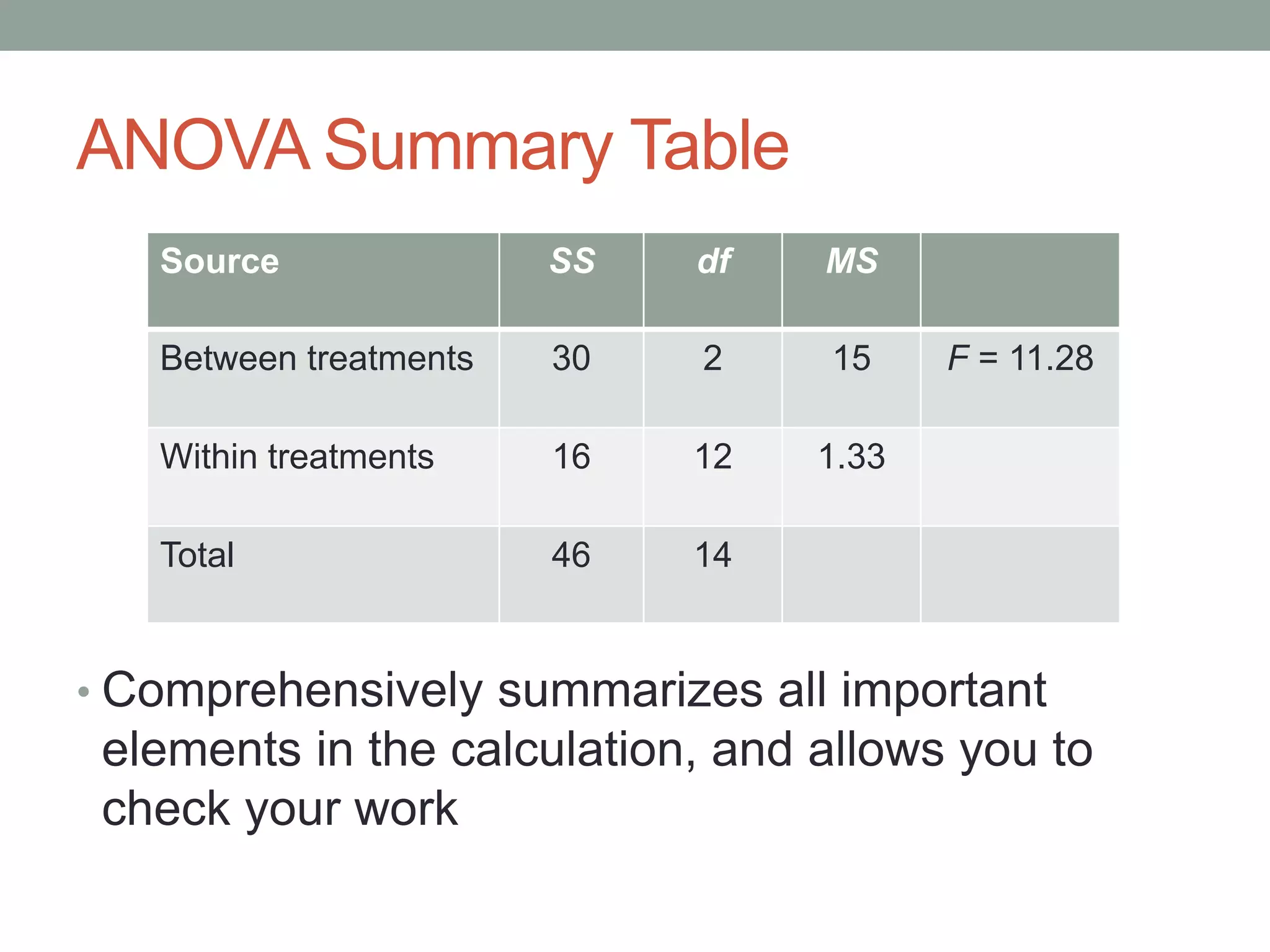

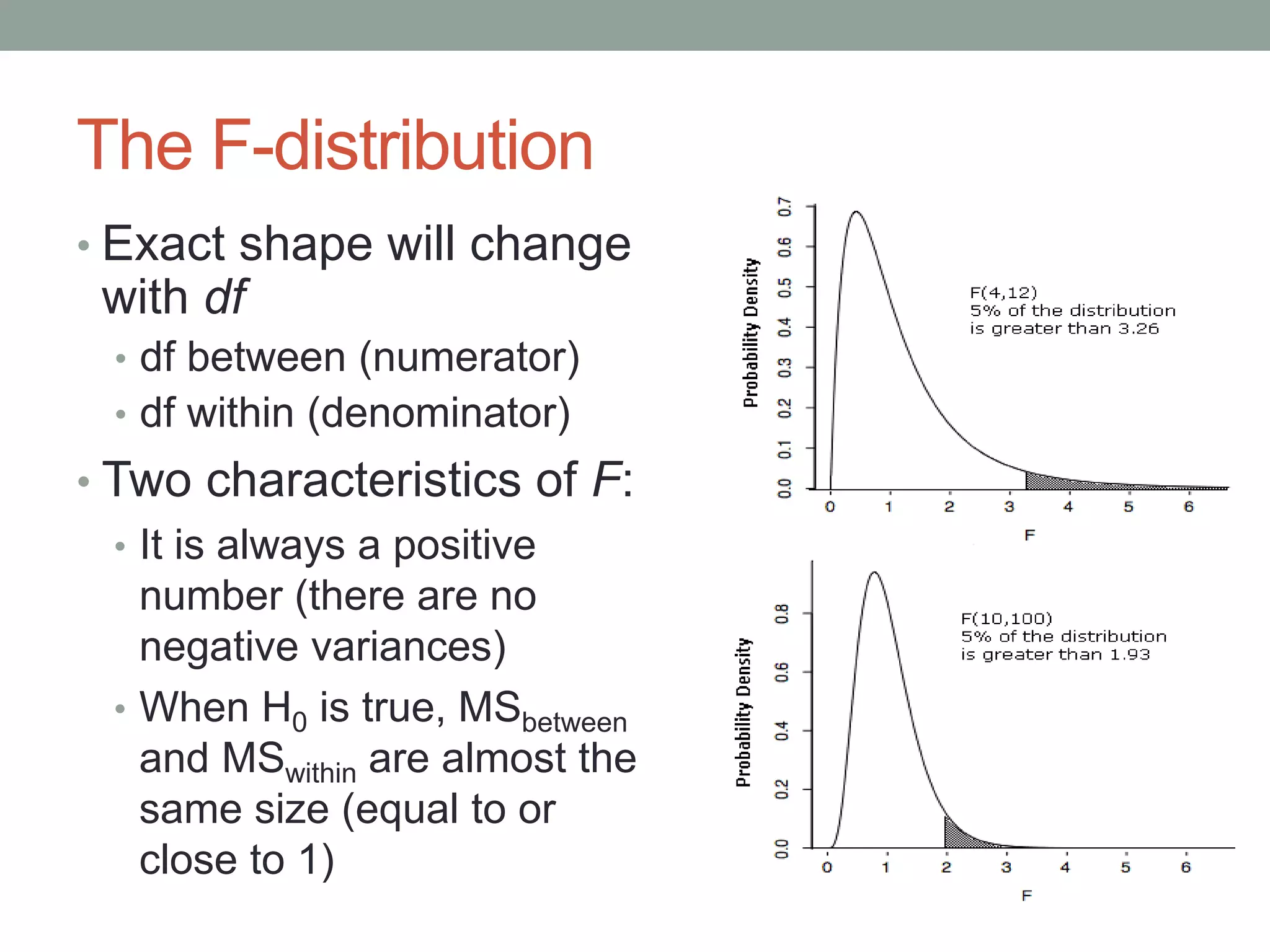

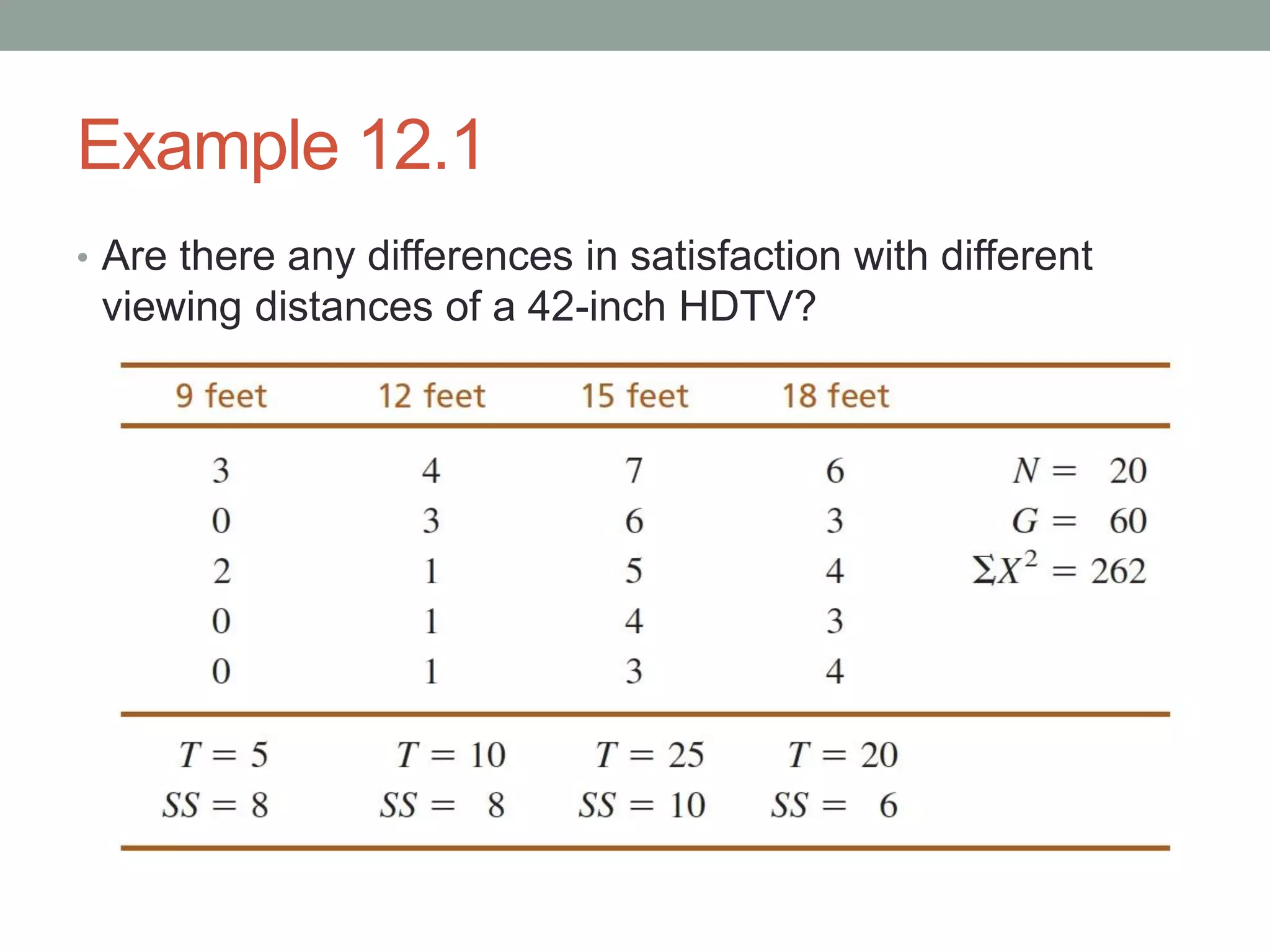

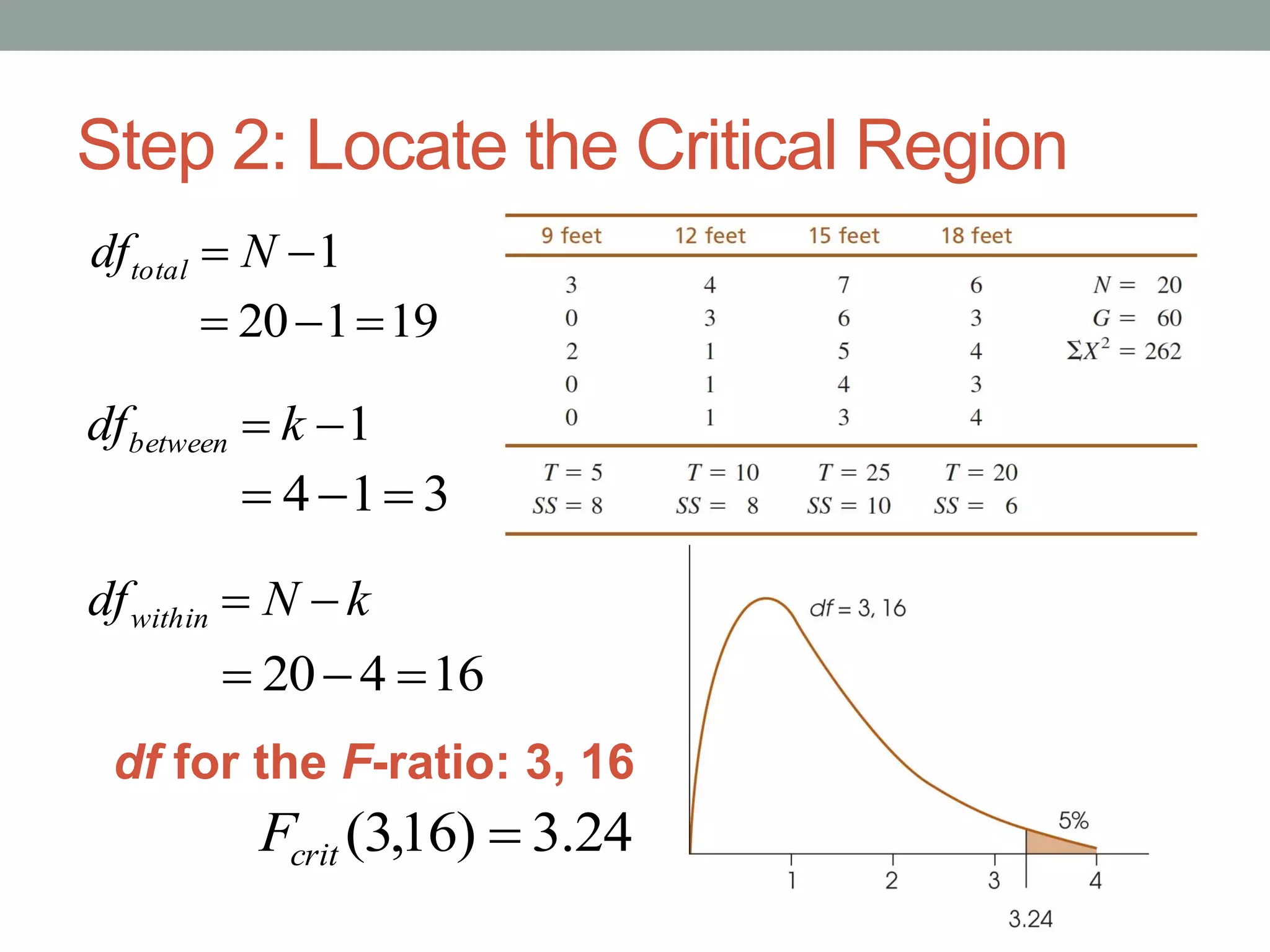

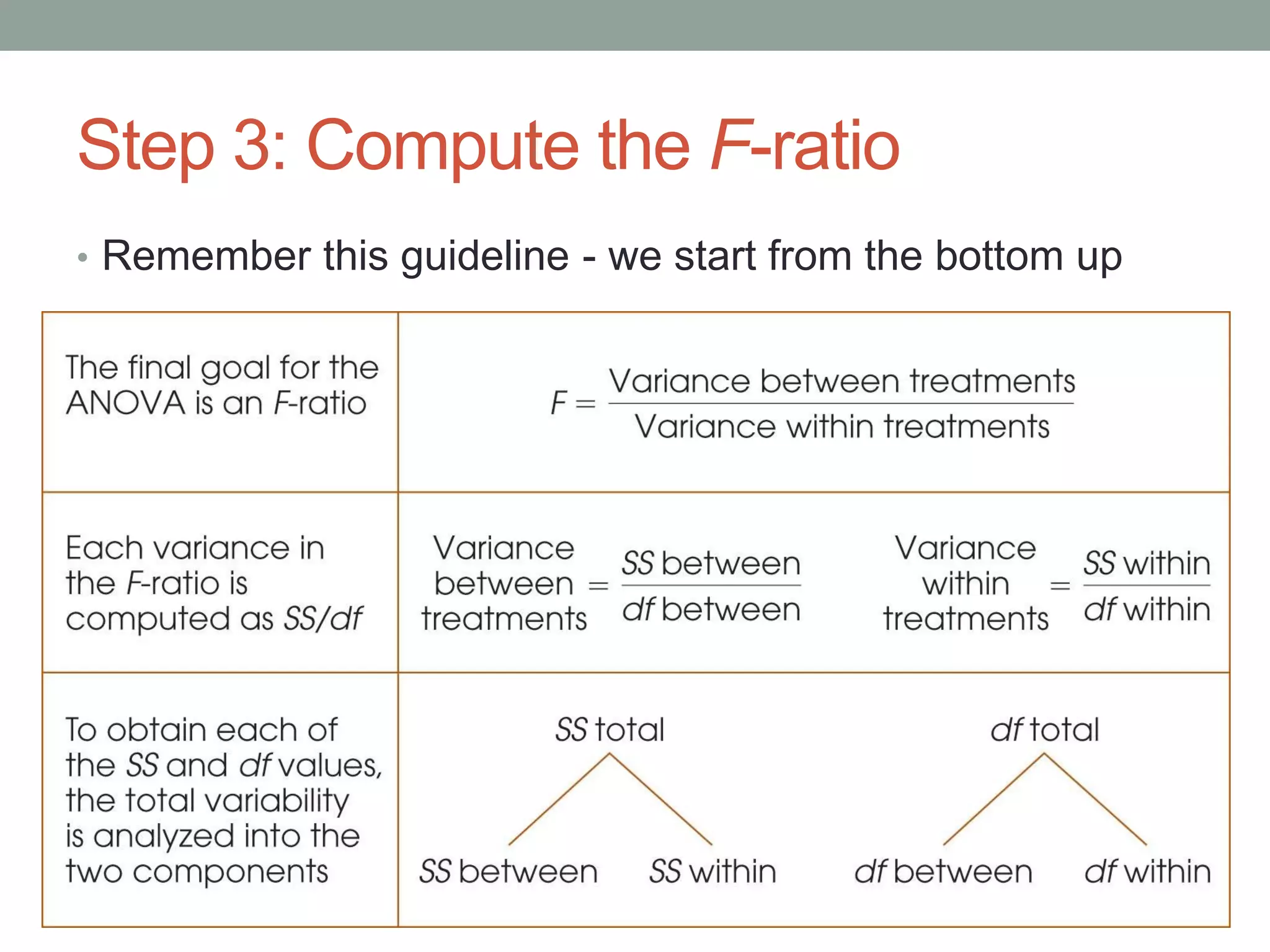

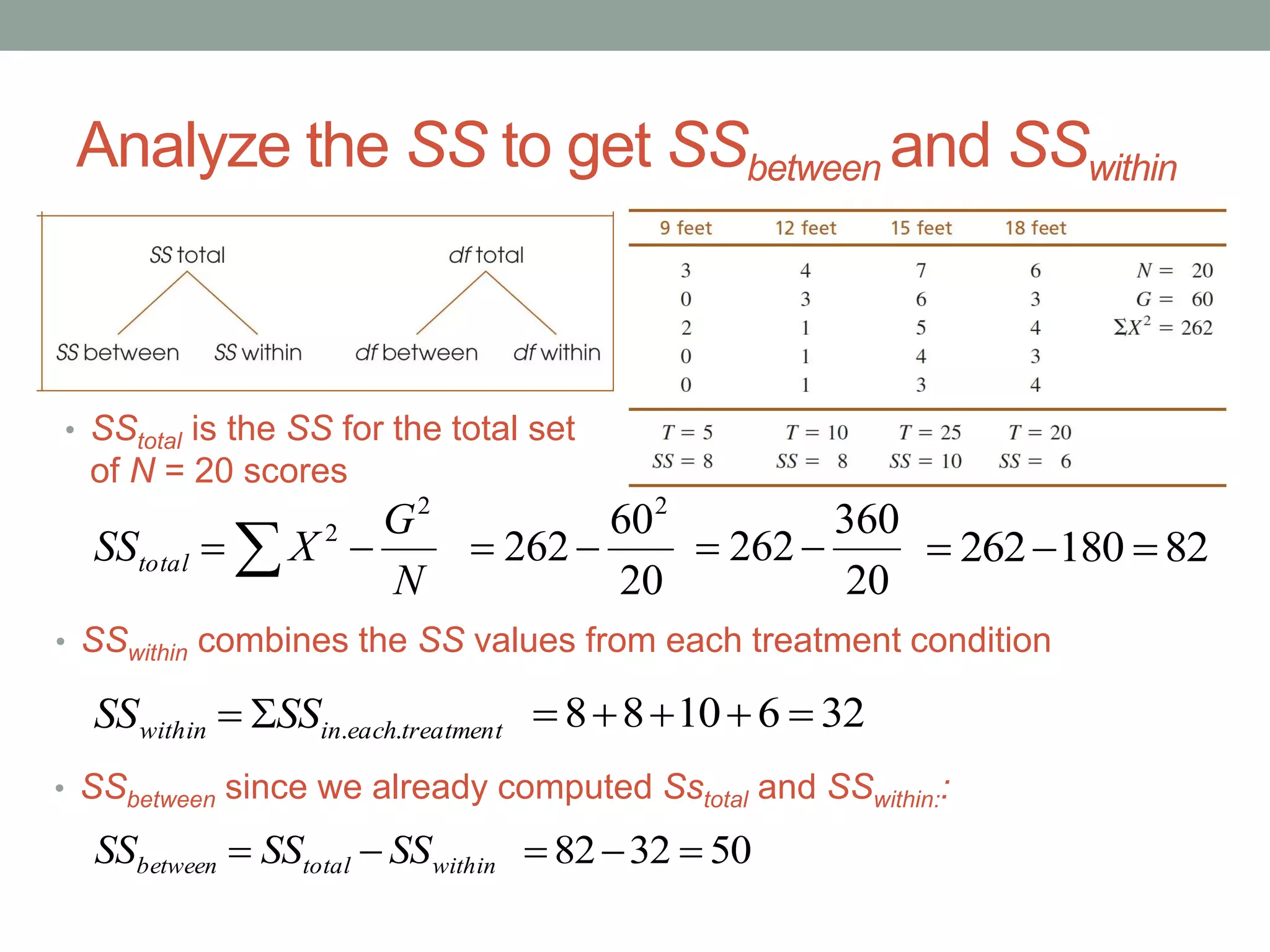

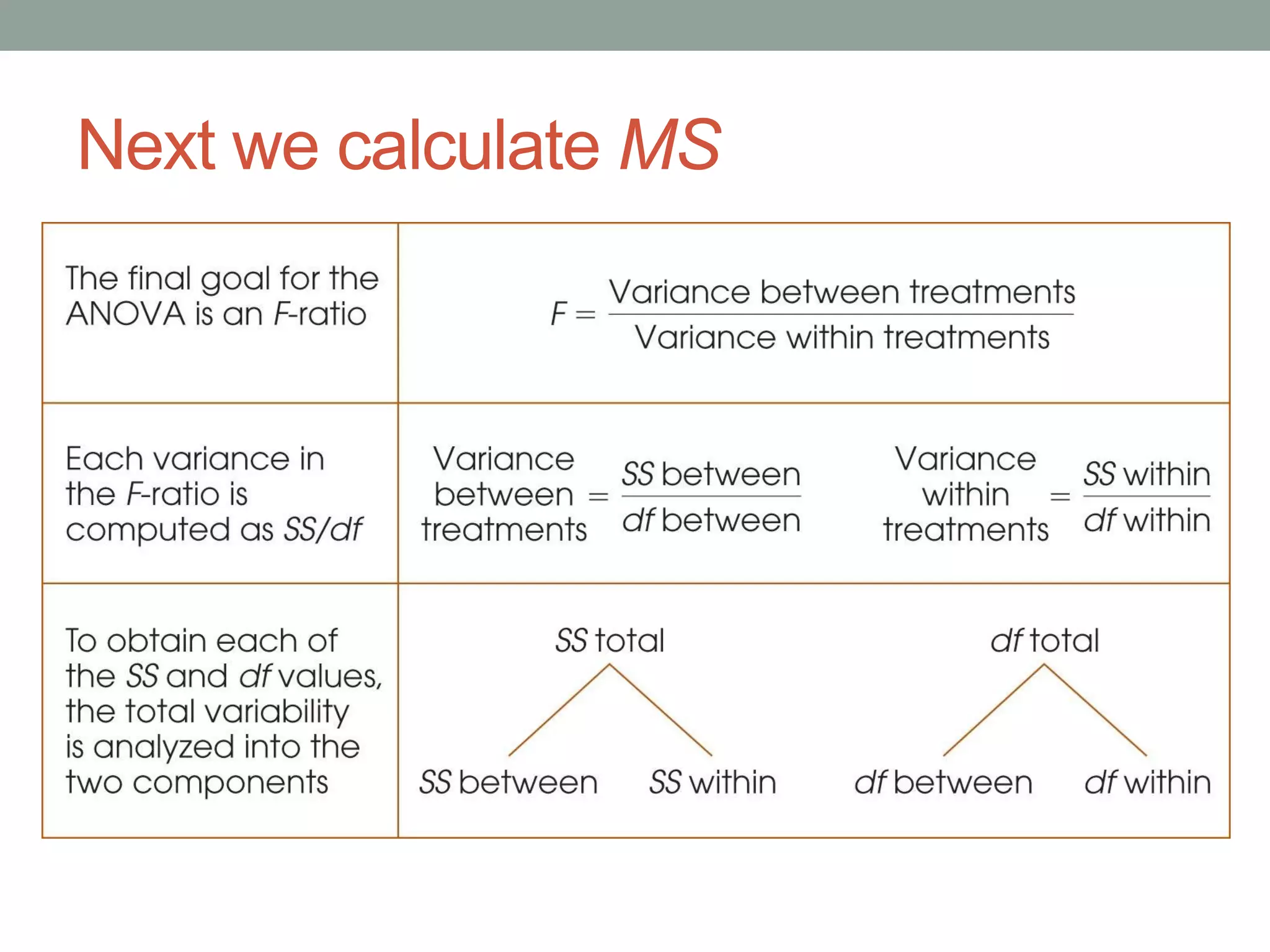

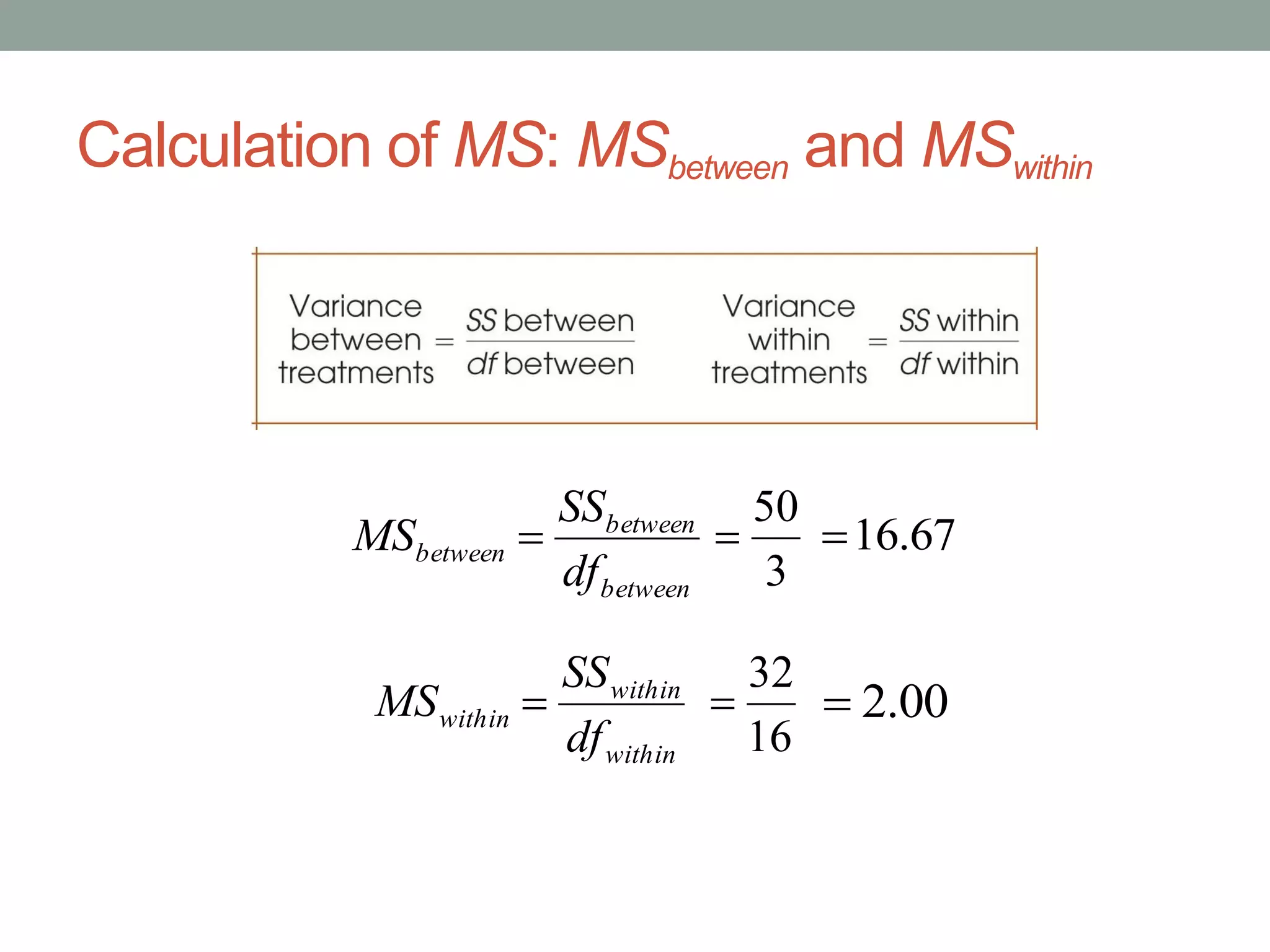

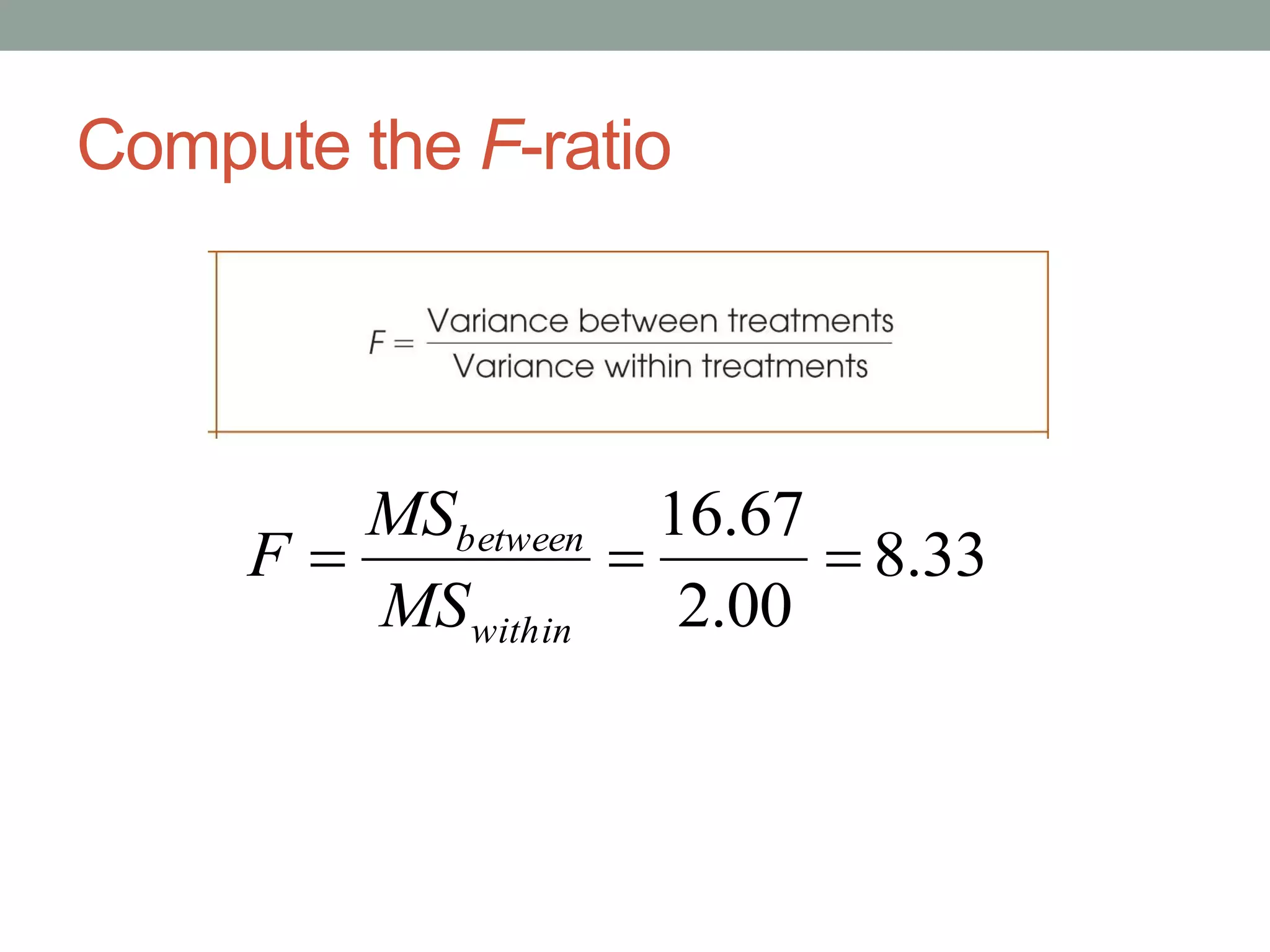

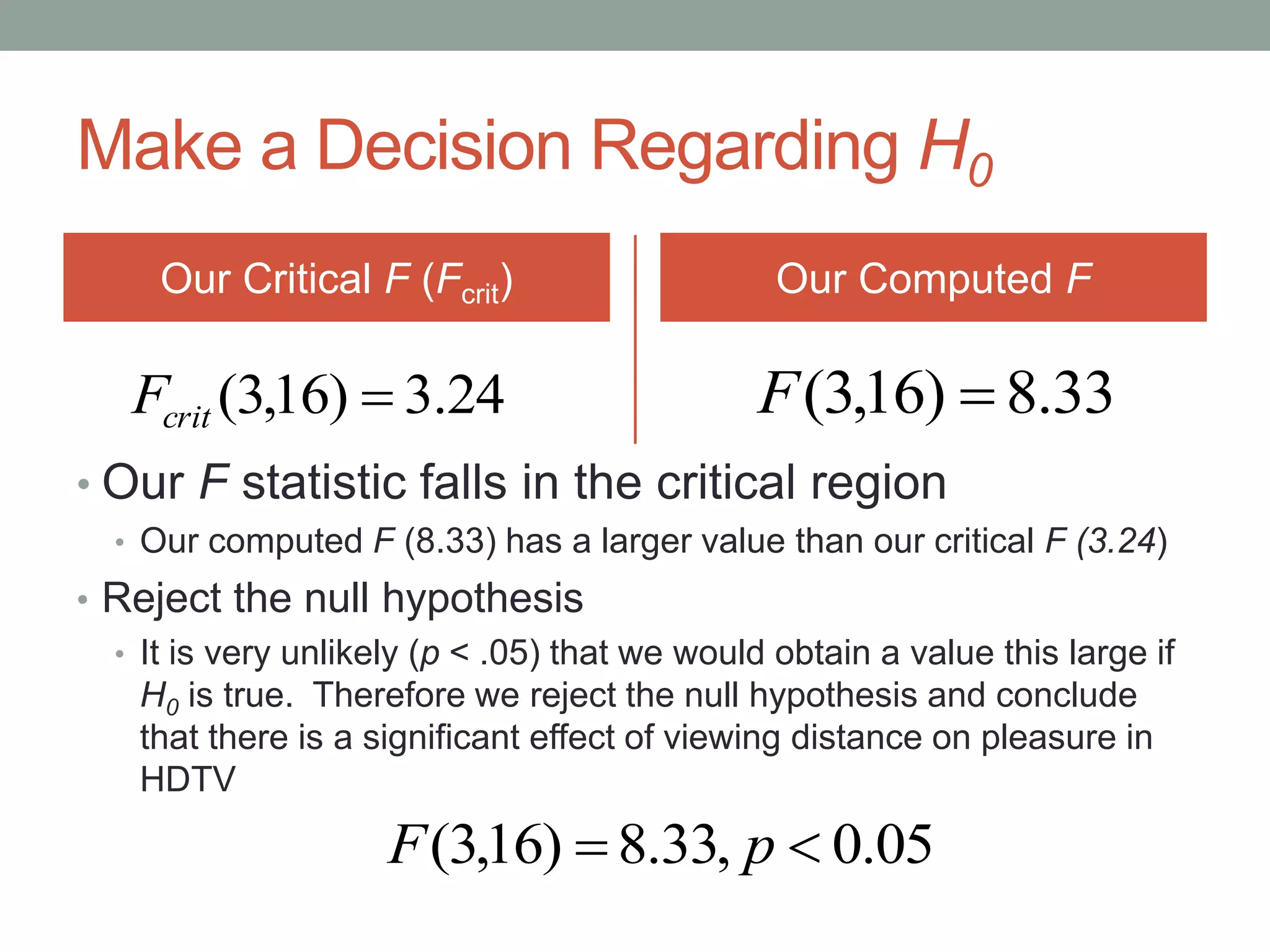

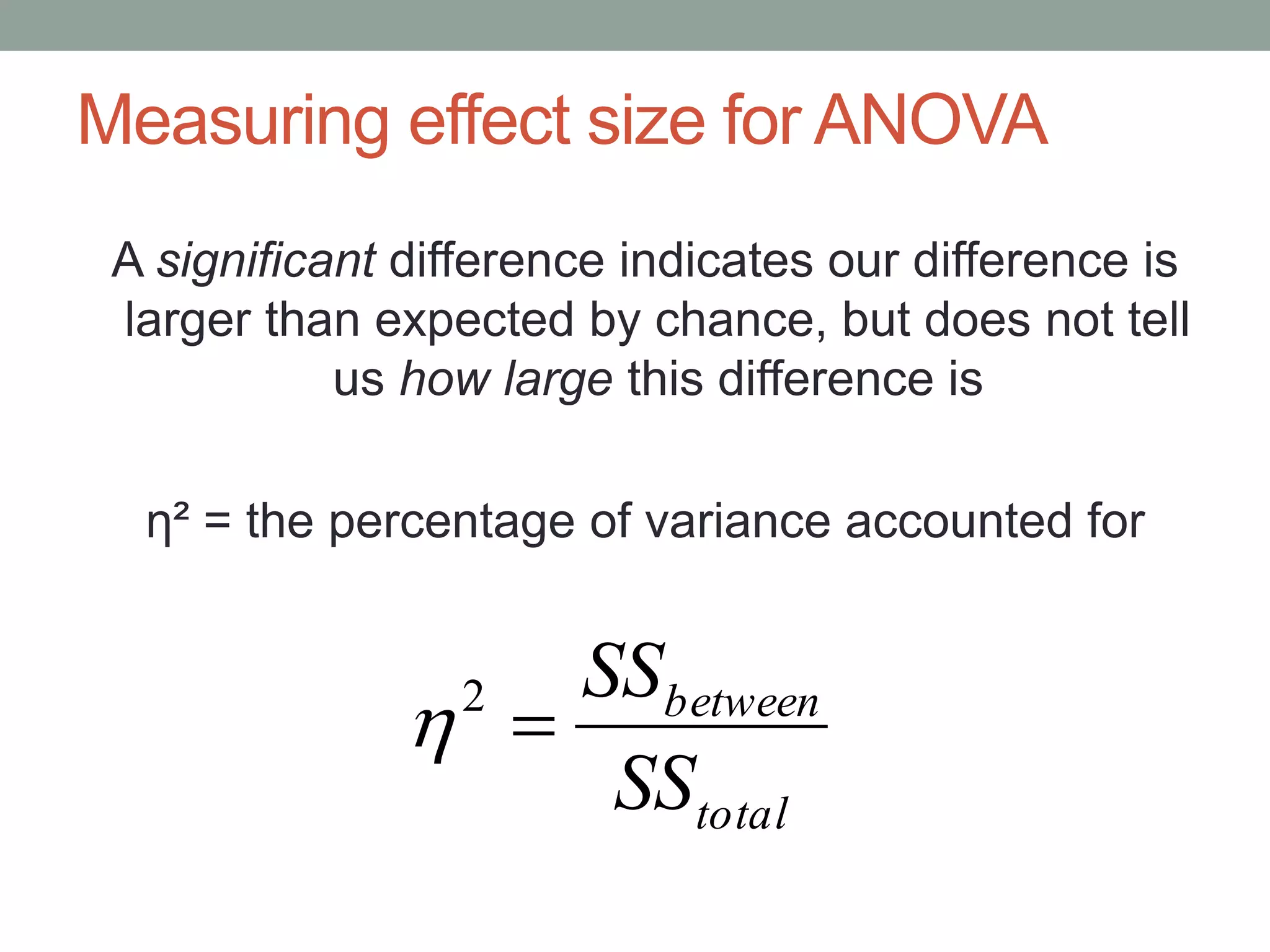

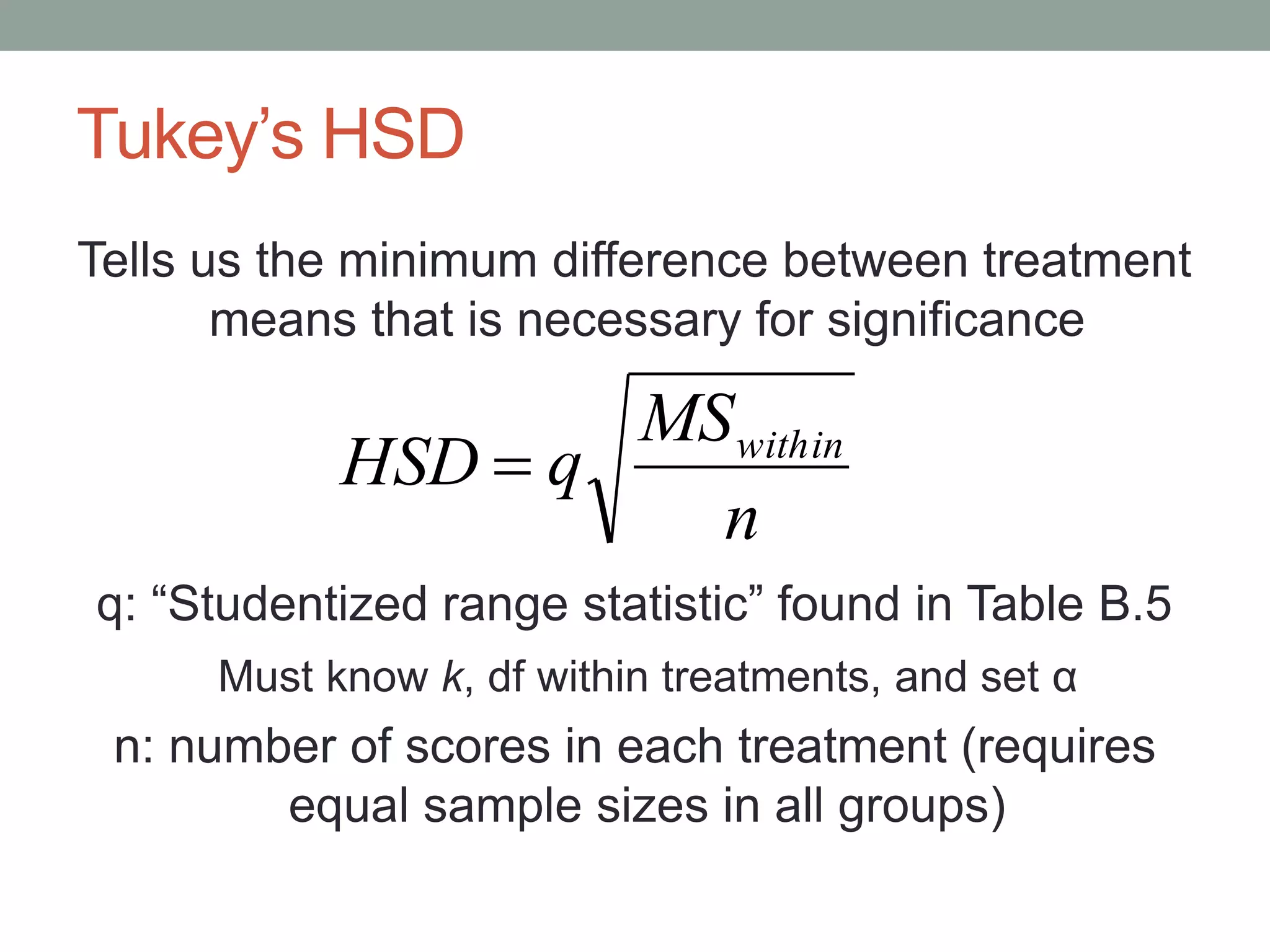

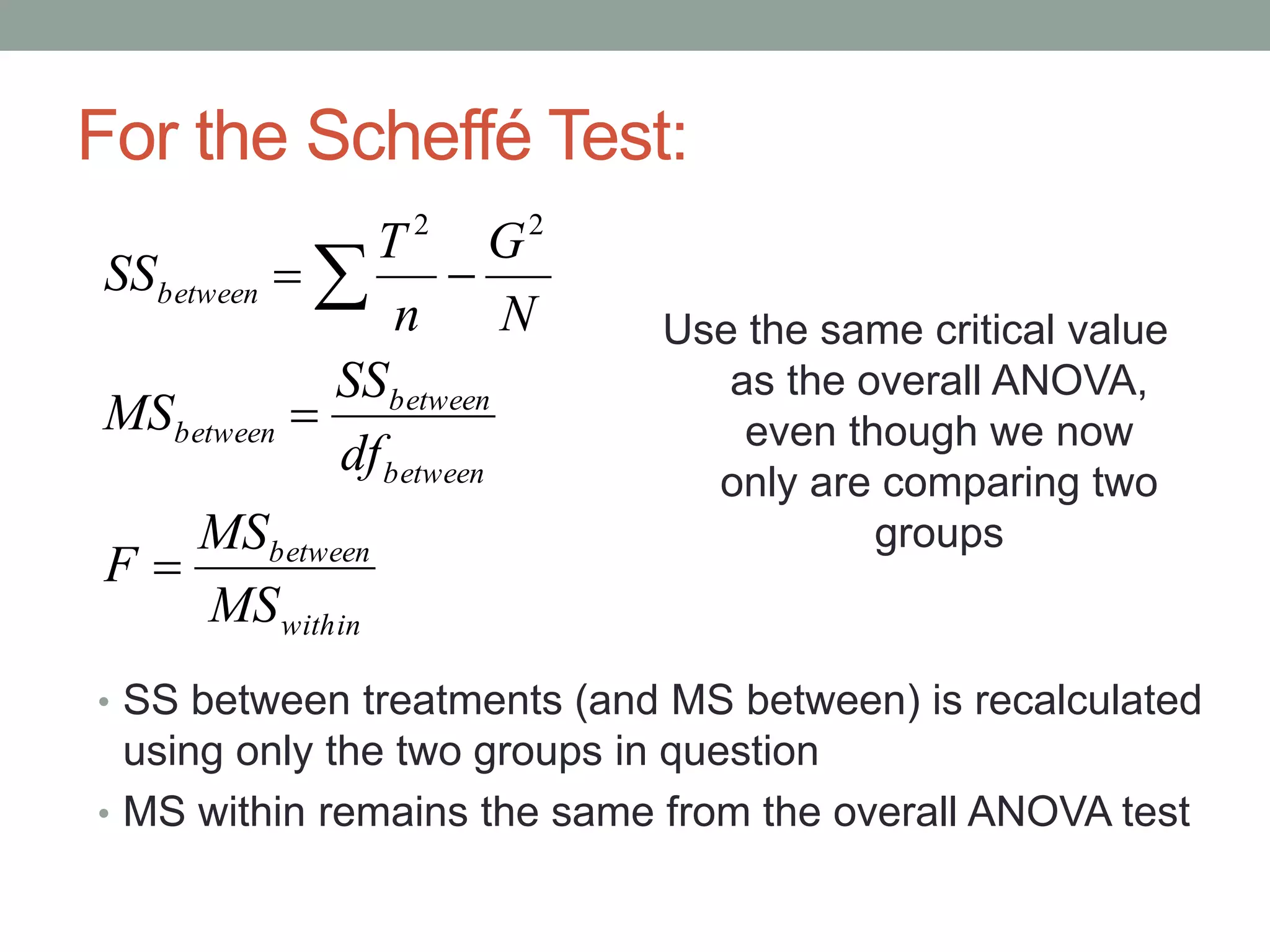

This document provides an introduction to analysis of variance (ANOVA). It discusses previous statistical tests learned, the logic and calculations of ANOVA, and examples of hypothesis testing using ANOVA. ANOVA allows comparison of three or more population means using their sample means. It partitions total variability into two components - variability between groups and variability within groups. The F-ratio compares the two and is evaluated to determine if there are statistically significant differences between population means. Post hoc tests are used after a significant F-ratio to determine exactly which group means differ.