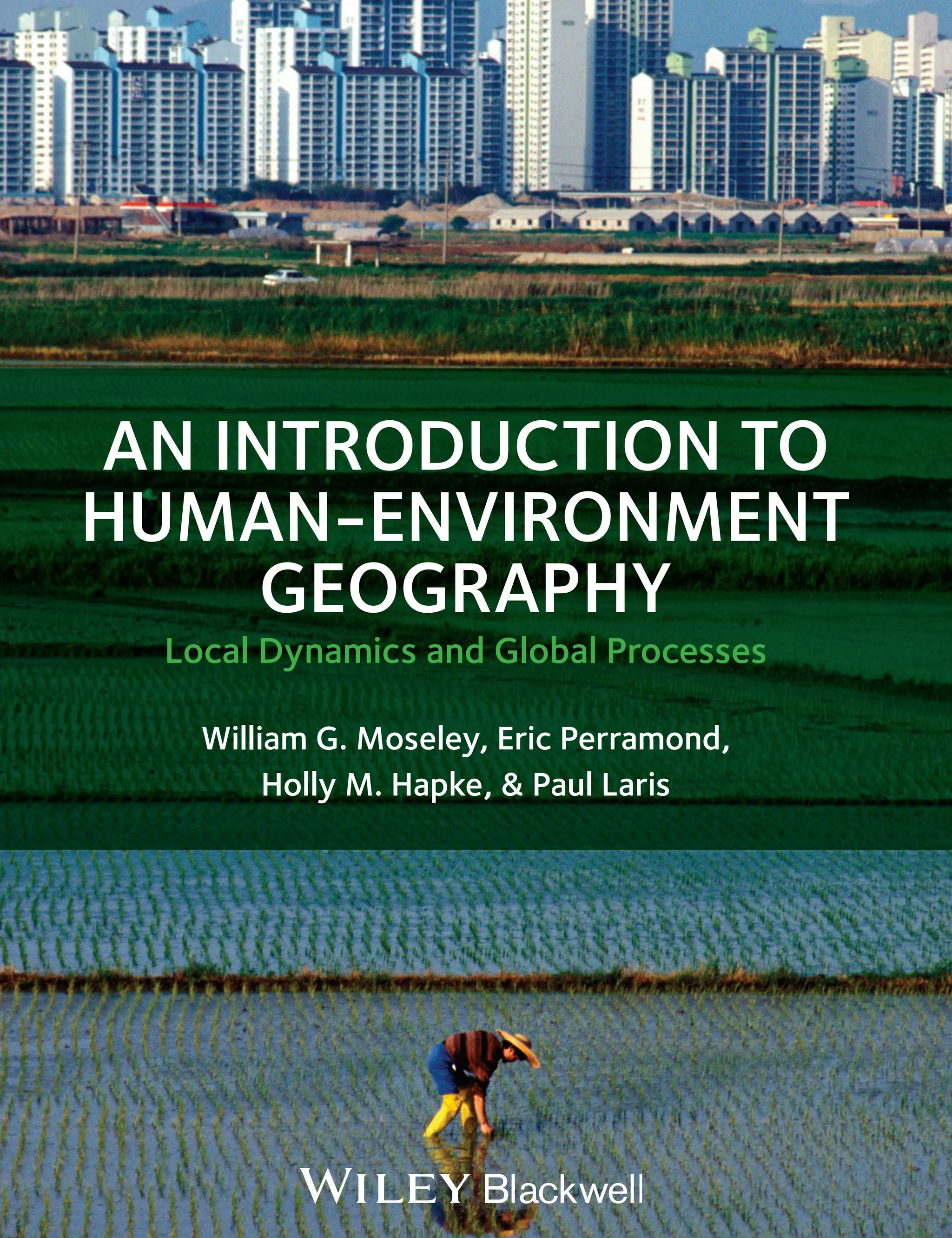

An Introduction To Humanenvironment Geography Local Dynamics And Global Processes Paperback William G Moseley

An Introduction To Humanenvironment Geography Local Dynamics And Global Processes Paperback William G Moseley

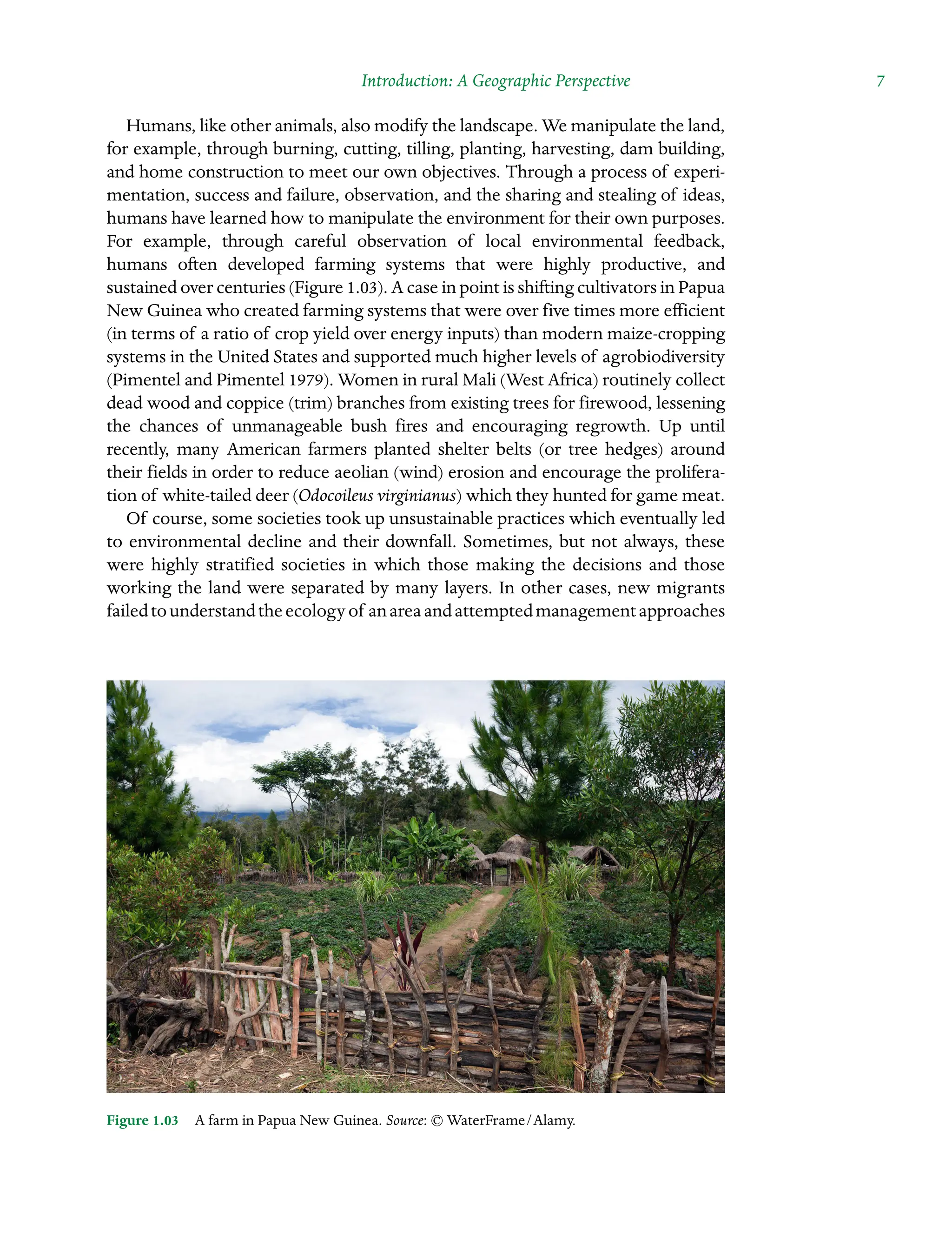

An Introduction To Humanenvironment Geography Local Dynamics And Global Processes Paperback William G Moseley