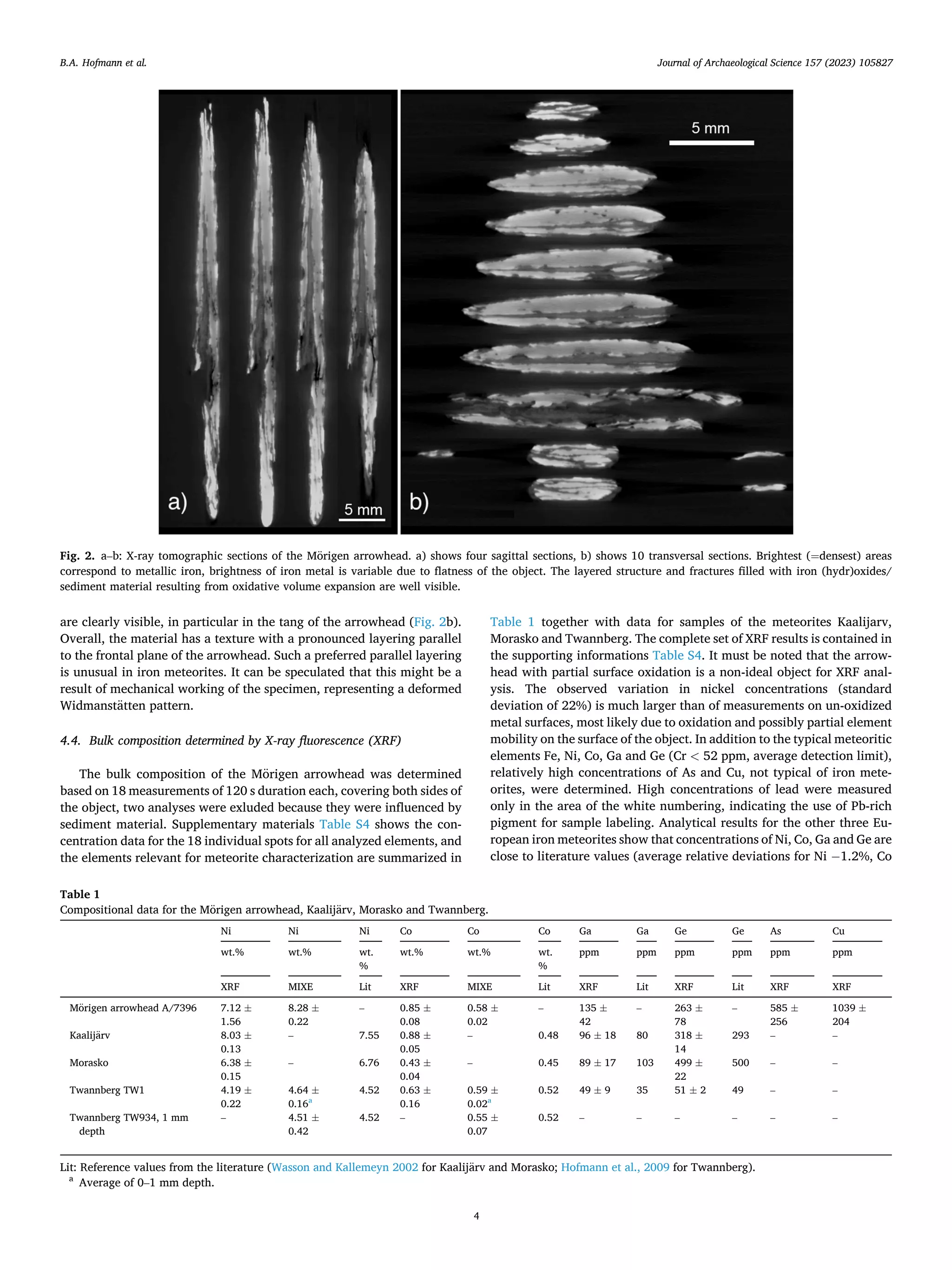

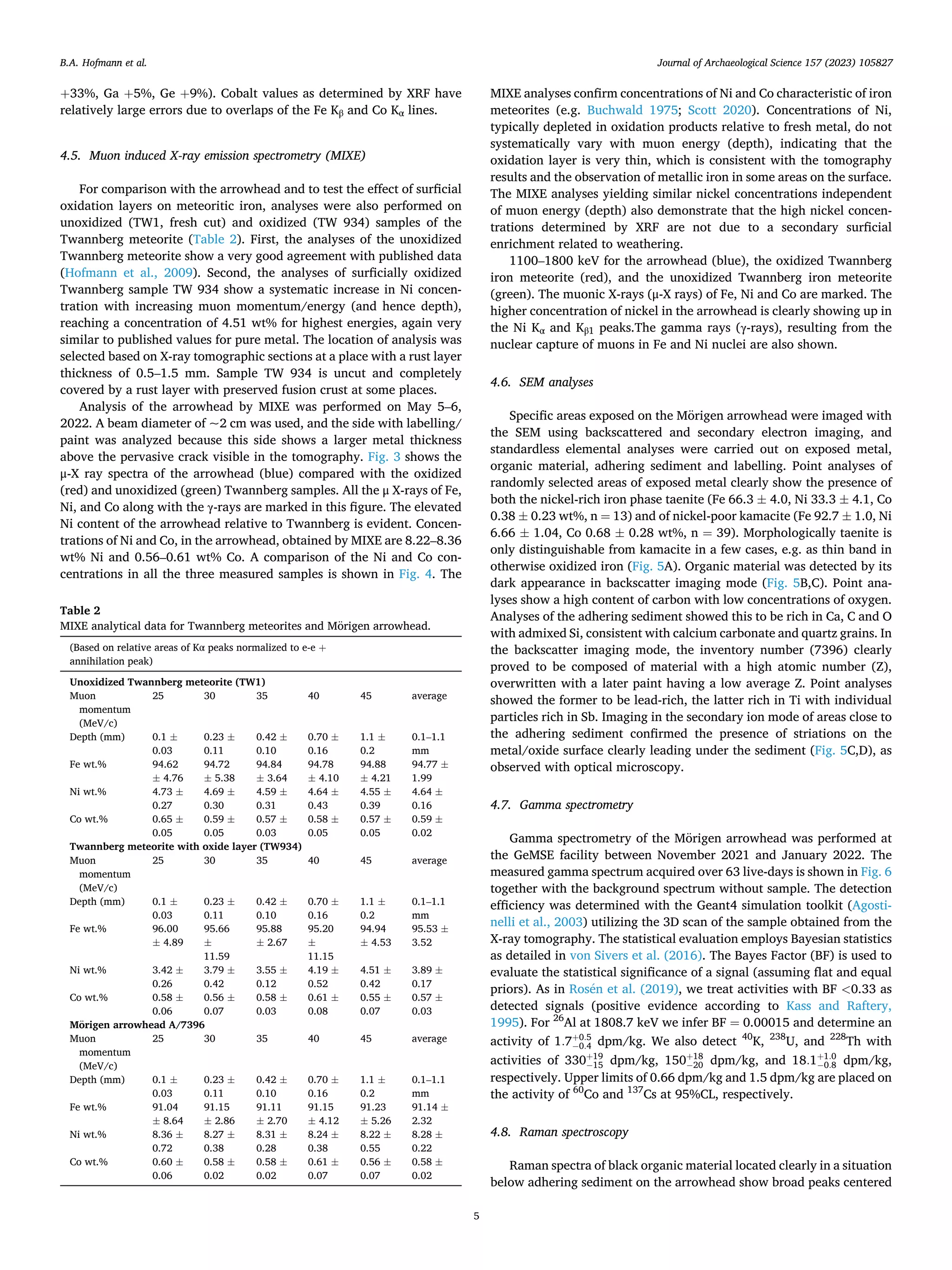

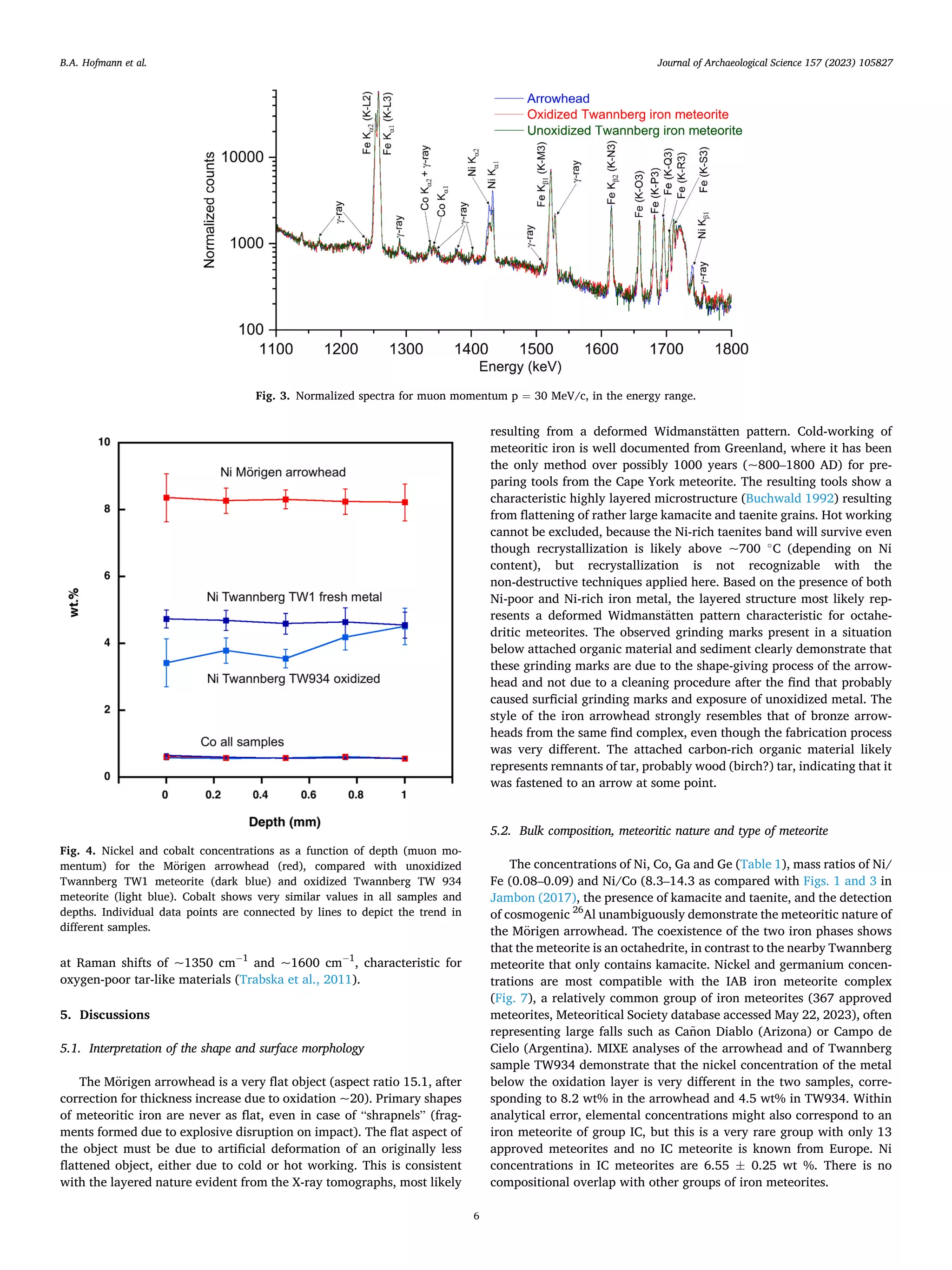

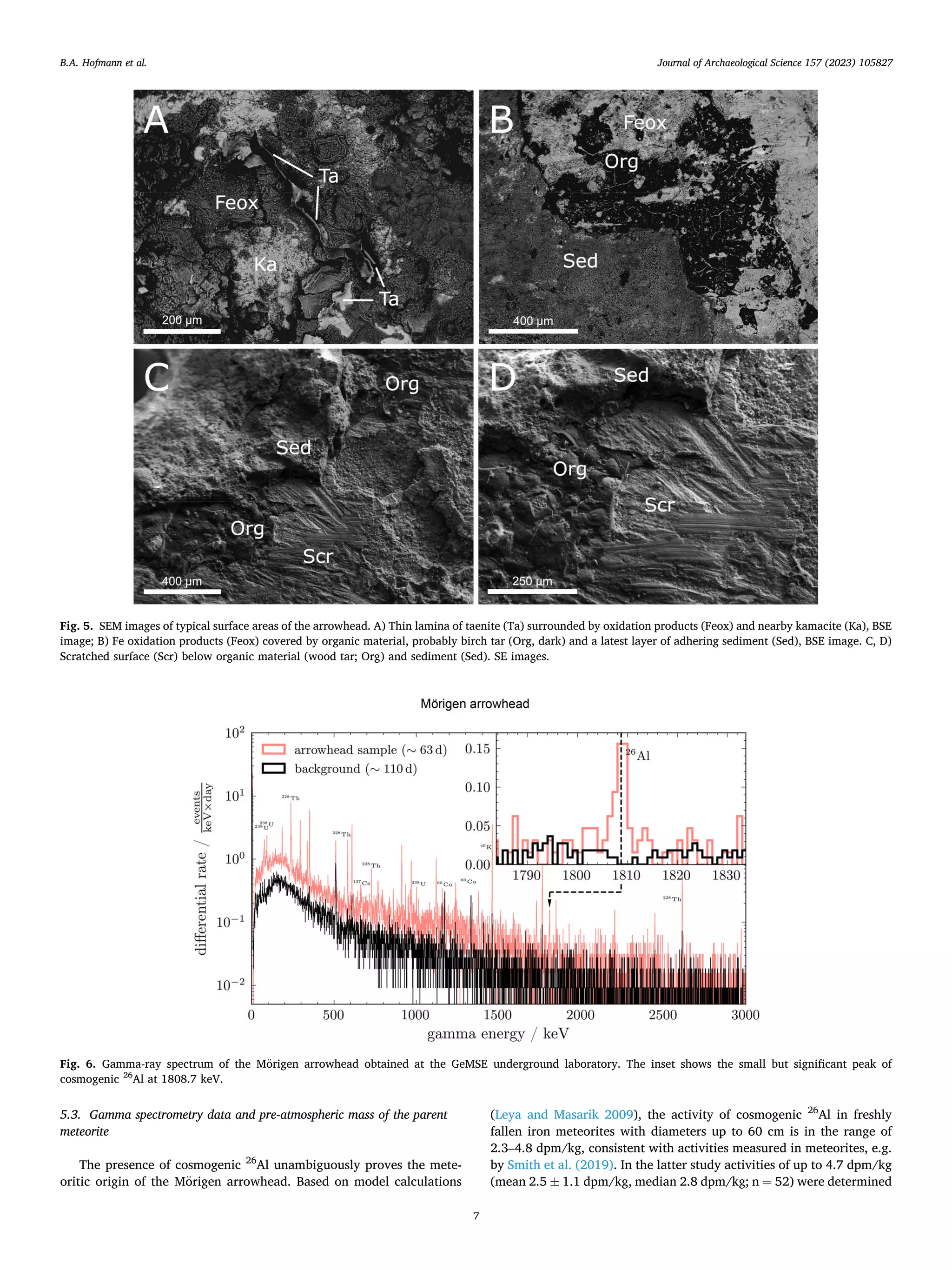

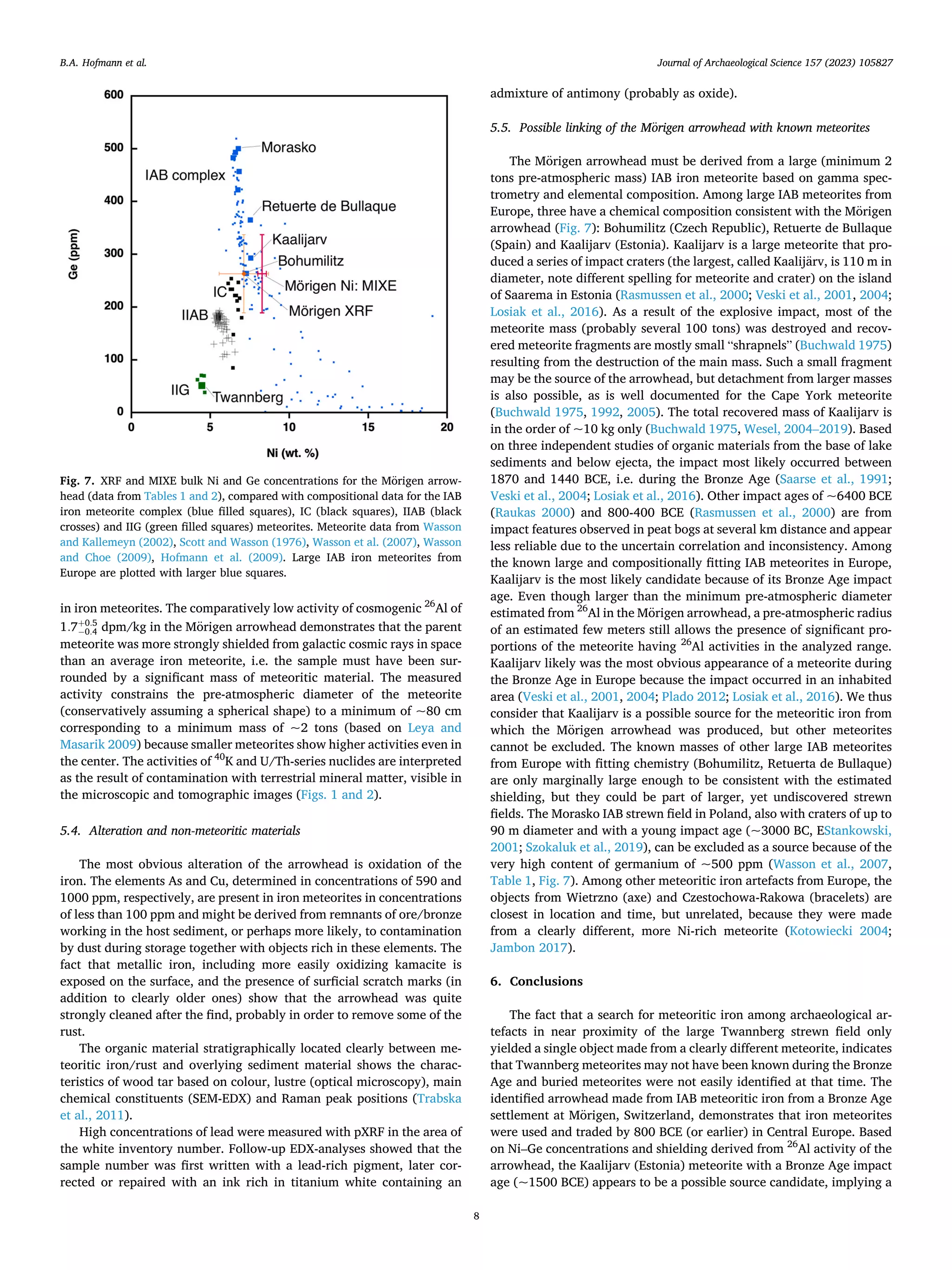

The document details the discovery of a meteoritic iron arrowhead from the late Bronze Age settlement of Mörigen, Switzerland, confirmed through advanced non-destructive testing methods. The artifact, weighing 2.9 g, has a unique nickel-rich composition likely sourced from the Kaalijarv meteorite in Estonia, dating to approximately 1500 years BCE. This finding highlights the potential for more meteoritic iron artifacts in Swiss archaeological collections, suggesting a broader historical context of metal usage before the advent of iron smelting.