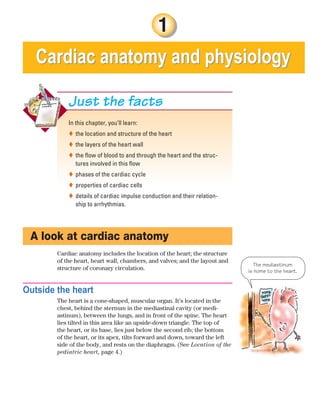

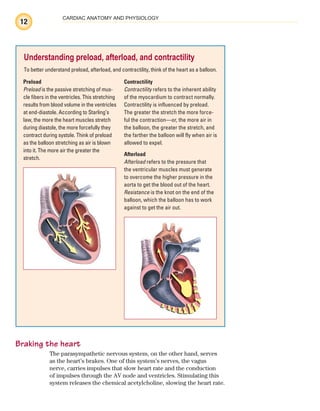

The document discusses cardiac anatomy, describing the location of the heart in the chest, its layers including the epicardium, myocardium, and endocardium, and the structures that surround and protect it like the pericardium. It also explains the flow of blood through the heart, noting the heart's chambers and valves, and gives an overview of the cardiac cycle and conduction system that generates heartbeats.

![Staff

Publisher

Chris Burghardt

Clinical Director

Joan M. Robinson, RN, MSN

Clinical Project Manager

Jennifer Meyering, RN, BSN, MS

Product Director

David Moreau

Product Manager

Jennifer K. Forestieri

Editor

Tracy S. Diehl

Art Director

Elaine Kasmer

Illustrator

Bot Roda

Design Assistant

Kate Zulak

Vendor Manager

Beth Martz

Associate Manufacturing Manager

Beth J. Welsh

Editorial Assistants

Karen J. Kirk, Jeri O’Shea, Linda K. Ruhf

The clinical treatments described and recommended

in this publication are based on research and consulta-

tion with nursing, medical, and legal authorities. To the

best of our knowledge, these procedures reflect cur-

rently accepted practice. Nevertheless, they can’t be

considered absolute and universal recommendations.

For individual applications, all recommendations must

be considered in light of the patient’s clinical condition

and, before administration of new or infrequently used

drugs, in light of the latest package-insert information.

The authors and publisher disclaim any responsibility

for any adverse effects resulting from the suggested

procedures, from any undetected errors, or from the

reader’s misunderstanding of the text.

© 2011 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights

reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part

of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or

transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic,

mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—

without prior written permission of the publisher, except

for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and

reviews and testing and evaluation materials provided by

publisher to instructors whose schools have adopted its

accompanying textbook. Printed in China. For informa-

tion, write Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 323 Norristown

Road, Suite 200, Ambler, PA 19002-2756.

ECGIE5E11010

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ECG interpretation made incredibly easy!. —

5th ed.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60831-289-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Electrocardiography. 2. Heart—Diseases—

Nursing. I. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

[DNLM: 1. Electrocardiography—Nurses’

Instruction. 2. Arrhythmias, Cardiac—Nurses’

Instruction. WG 140 E172 2011]

RC683.5.E5E256 2011

616.1’207547—dc22

ISBN-13: 978-1-60831-289-4 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-60831-289-5 (alk. paper) 2010022956

iv

ECG_FM.indd iv

ECG_FM.indd iv 7/8/2010 12:48:24 PM

7/8/2010 12:48:24 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ekginterpretationmadeincrediblyeasycoll-221214201734-32685674/85/ahas-6-320.jpg)

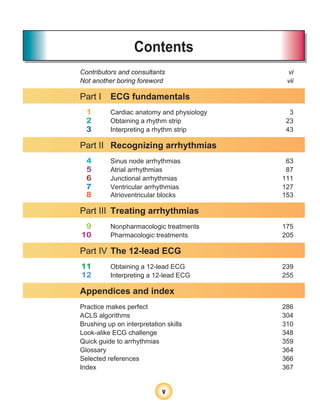

![34

OBTAINING A RHYTHM STRIP

soft tissues or close to bone, not over bony prominences, thick

muscles, or skin folds. Those areas can produce ECG artifacts—

waveforms not produced by the heart’s electrical activity.

Prepare the skin

Next, prepare the patient’s skin. To begin, wash the patient’s chest

with soap and water and then dry it thoroughly. Because hair

may interfere with electrical contact, clip dense hair with clippers

or scissors. Then use the special rough patch on the back of the

electrode, a dry washcloth, or a gauze pad to briskly rub each site

Understanding the EASI system

The five-lead EASI (reduced lead continuous 12-lead electrocardiogram [ECG]) configu-

ration gives a three-dimensional view of the electrical activity of the heart from the fron-

tal, horizontal, and sagittal planes. This provides 12 leads of information. A mathematical

calculation in the electronics of the monitoring system is applied to the information,

creating a derived 12-lead ECG.

Placement of the electrodes for the EASI system includes:

E lead:

• lower part of the sternum atthe level of the fifth intercostal space

A lead:

• left midaxillary line at the level of the fifth intercostal space

S lead:

• upperpart of the sternum

I lead:

• right midaxillary line at the level of the fifth intercostal space

Ground:

• anywhere on the torso.

E

A

S

Ground

I

Memory

jogger

To help

you re-

member where to

place electrodes

in a five-electrode

configuration, think

of the phrase “White

to the upper right.”

Then think of snow

over trees (white

electrode above

green electrode) and

smoke over fire (black

electrode above red

electrode). And of

course, chocolate

(brown electrode) lies

close to the heart.

White Black

Green Red

Brown

ECG_Chap02.indd 34

ECG_Chap02.indd 34 7/8/2010 4:16:57 PM

7/8/2010 4:16:57 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ekginterpretationmadeincrediblyeasycoll-221214201734-32685674/85/ahas-44-320.jpg)

![140

VENTRICULAR ARRHYTHMIAS

collapse. Most patients with ventricular tachycardia have weak or

absent pulses. Low cardiac output will cause hypotension and a

decreased level of consciousness (LOC) leading to unresponsive-

ness. Ventricular tachycardia may precipitate angina, heart failure,

or a substantial decrease in organ perfusion.

How you intervene

Treatment depends on whether the patient’s pulse is detectable

or undetectable. A patient with pulseless ventricular tachycardia

receives the same treatment as one with ventricular fibrillation

and requires immediate defibrillation and CPR. Treatment for the

patient with a detectable pulse depends on whether his condition

is stable or unstable and has monomorphic or polymorphic QRS

complexes.

Unstable patients generally have heart rates greater than 150

beats/minute. They may also have hypotension, shortness of

breath, an altered LOC, heart failure, angina, or MI—conditions

that indicate cardiac decompensation. These patients are treated

immediately with direct-current synchronized cardioversion.

Typical tachycardia complex

A hemodynamically stable patient with monomorphic ven-

tricular tachycardia is treated differently. First, administer

amiodarone following advanced cardiac life support (ACLS)

protocols to correct the rhythm disturbance. If the drug doesn’t

correct the disturbance, prepare the patient for synchronized

cardioversion.

If the patient has polymorphic ventricular tachycardia with

a normal QT interval, correct ischemia and electrolyte imbal-

ances. Then adminster beta-adrenergic blockers, lidocaine,

amiodarone, or procainamide following ACLS protocol. Again,

if drug therapy is unsuccessful, synchronized cardioversion is

performed.

Correct electrolyte abnormalities in the patient with polymor-

phic ventricular tachycardia with a prolonged QT interval and ad-

minister magnesium I.V. If the rhythm persists, prepare the patient

for overdrive pacing.

Patients with chronic, recurrent episodes of ventricular tachy-

cardia who are unresponsive to drug therapy may have a cardio-

verter-defibrillator implanted. This device is a more permanent

solution to recurrent episodes of ventricular tachycardia. (For

more information about the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

[ICD], see chapter 9.)

Treatment for the

patient in

V-tach depends on

whether his pulse

is detectable or

undetectable.

ECG_Chap07.indd 140

ECG_Chap07.indd 140 7/7/2010 5:59:15 PM

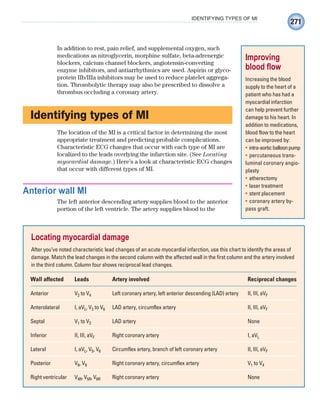

7/7/2010 5:59:15 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ekginterpretationmadeincrediblyeasycoll-221214201734-32685674/85/ahas-150-320.jpg)