This document is the preface to the 7th edition of the textbook "A Geology for Engineers" by authors F.G.H. Blyth and M.H. de Freitas. It discusses the structure and features of the new edition, which has been completely revised and expanded with three new chapters. The preface is intended to help teachers utilizing the textbook in their geology courses for engineering students, as well as to aid students in their study of geology. Key features for teachers include chapter structure, illustrations, and support for practical work. Key features for students include text format, comprehensive headings, and references to assist further learning.

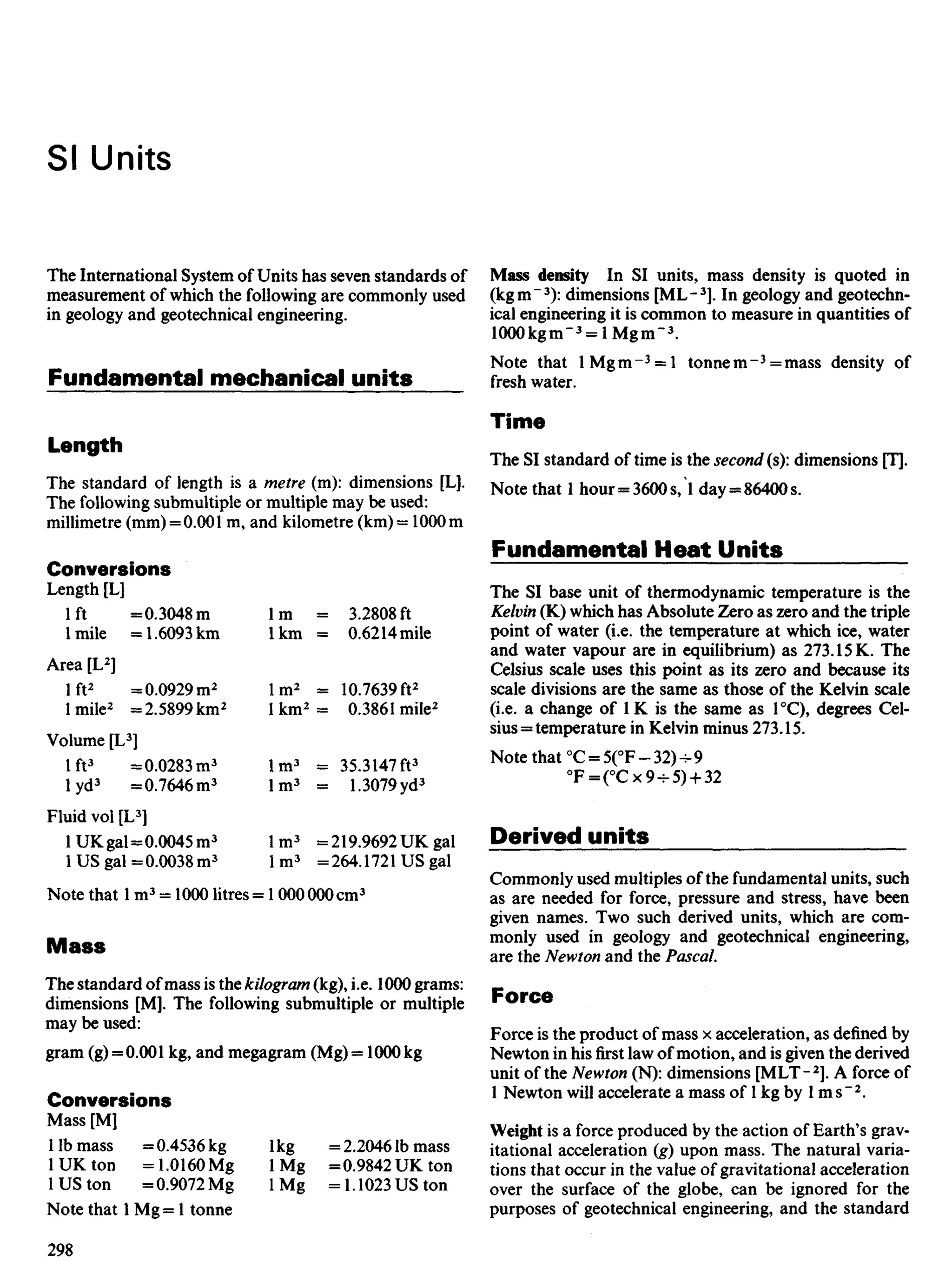

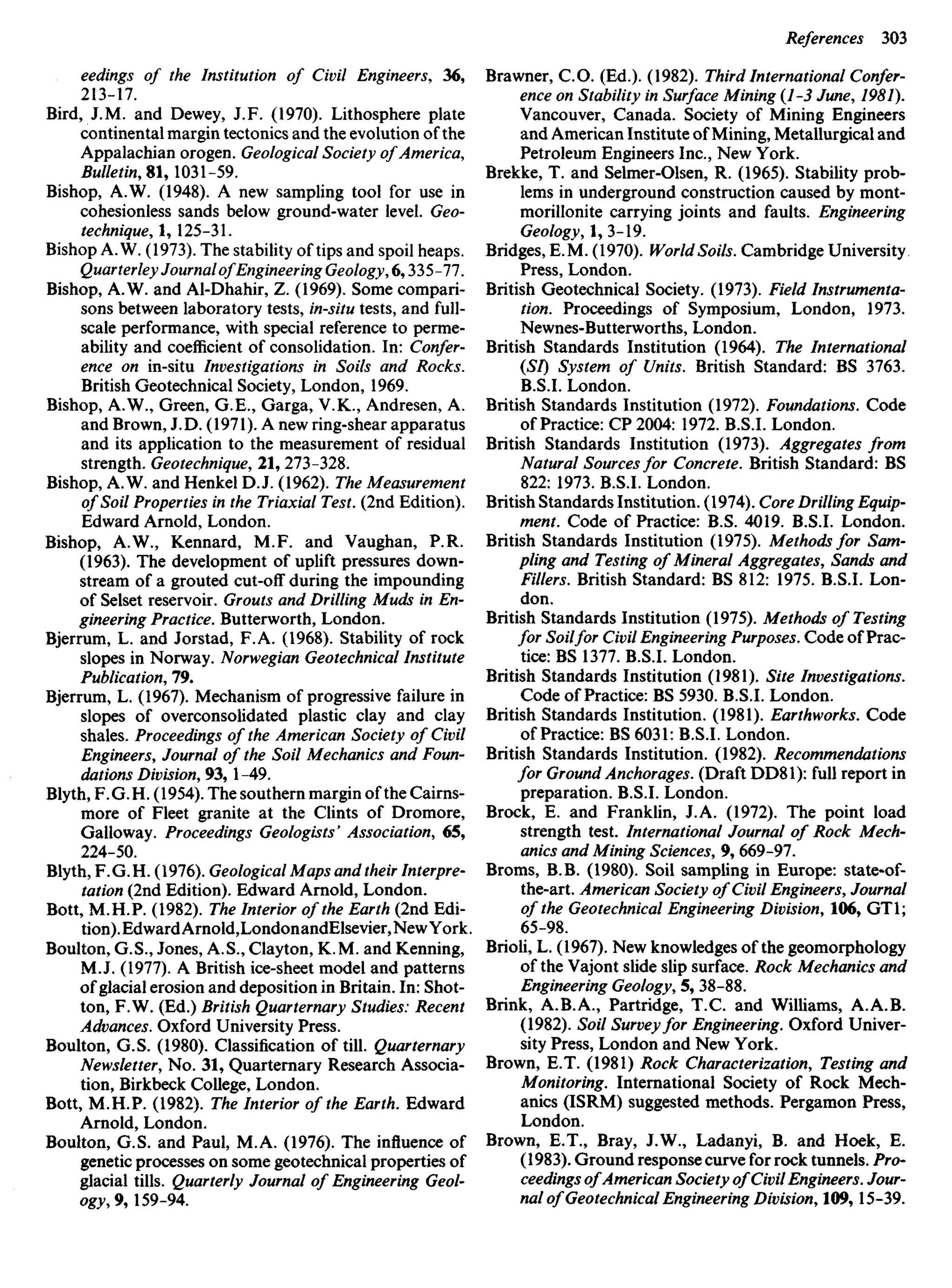

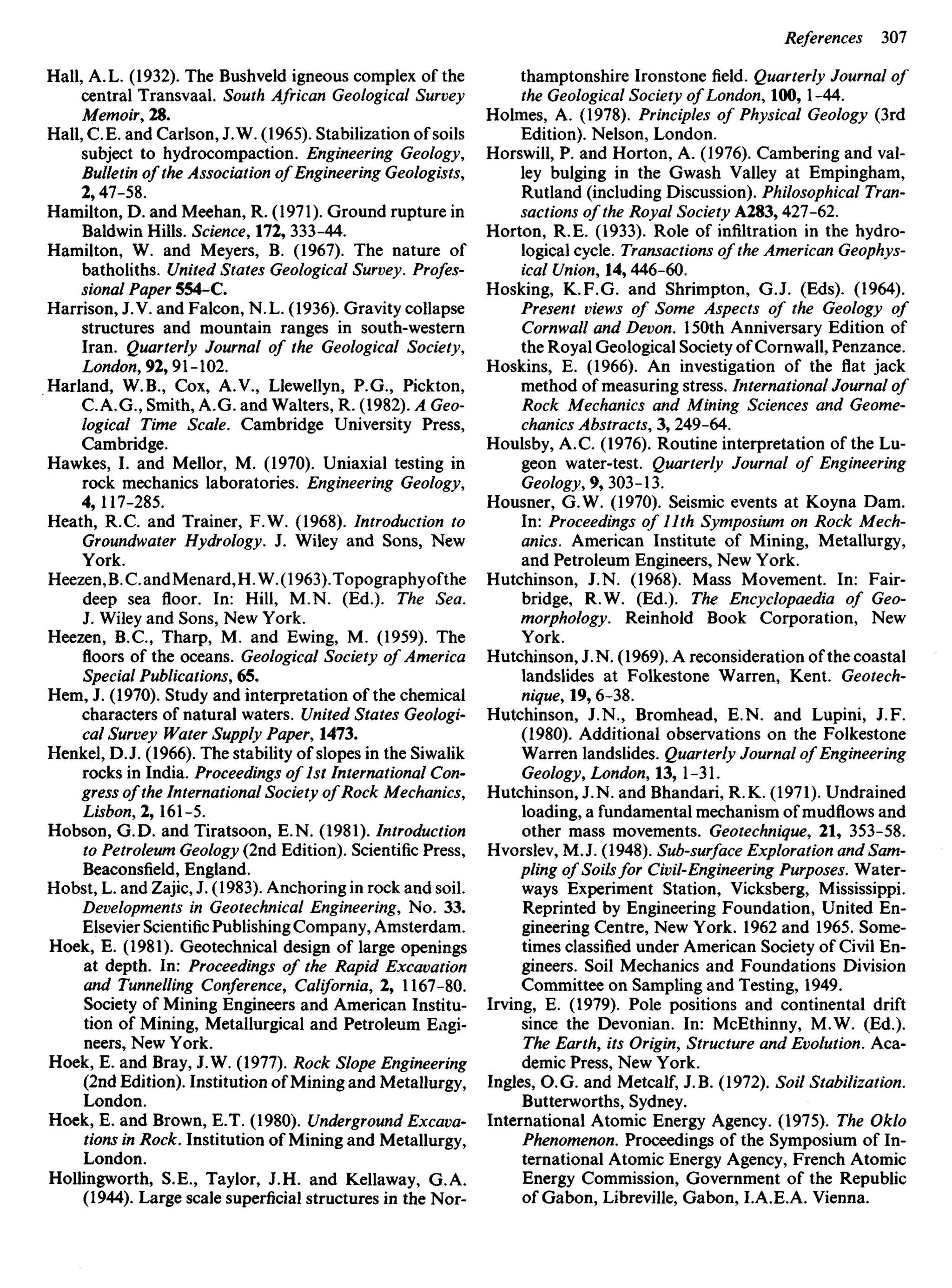

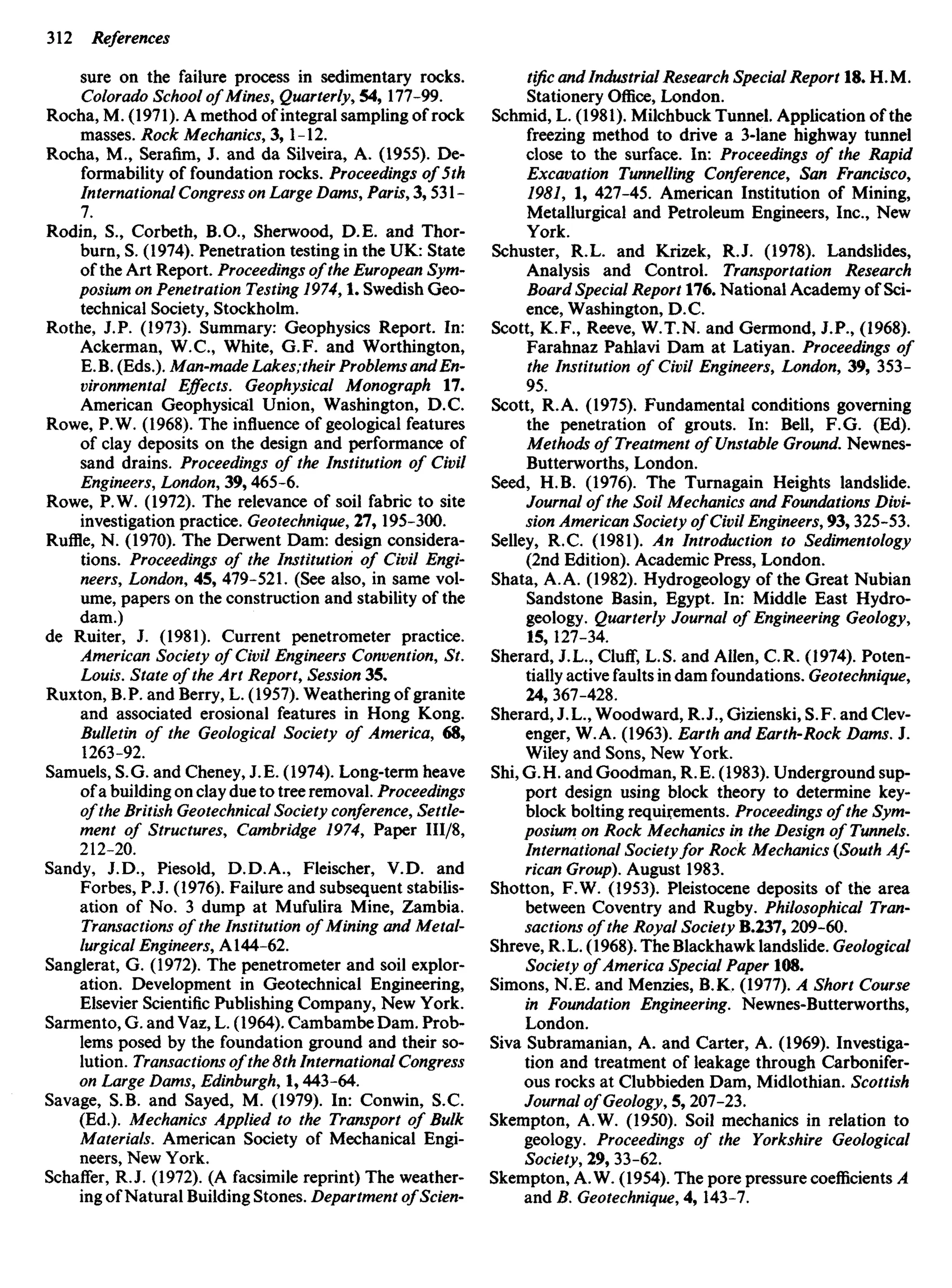

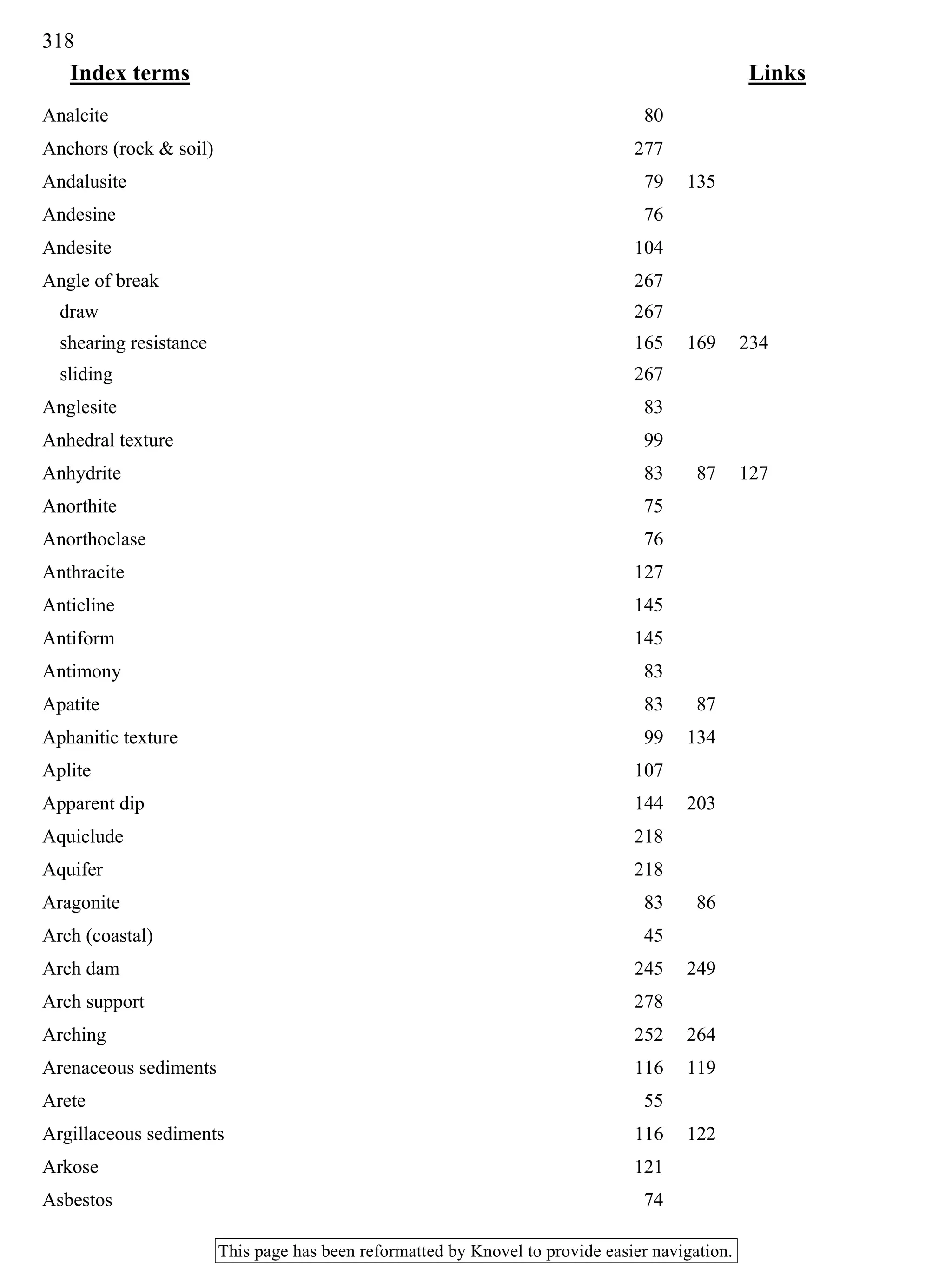

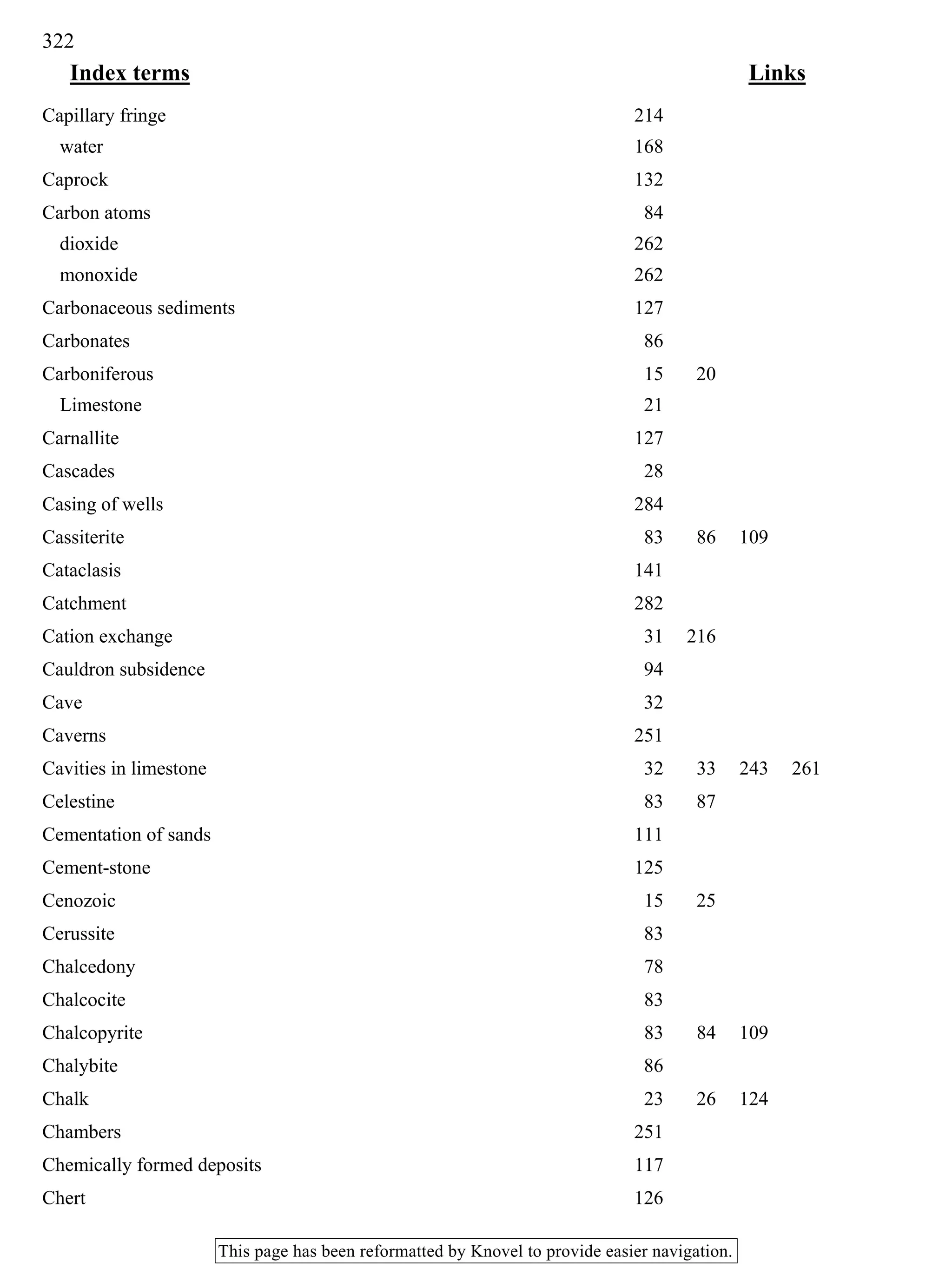

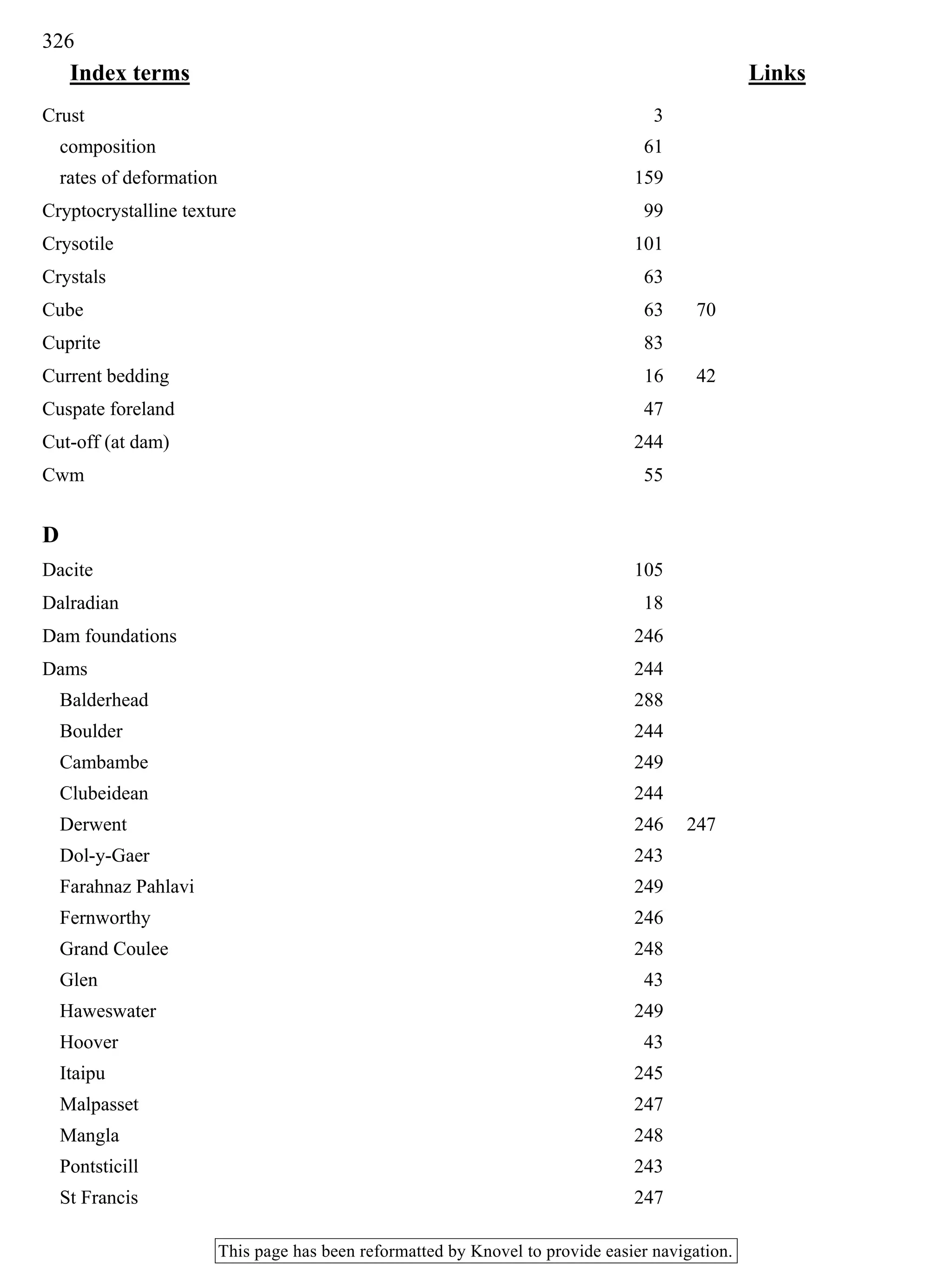

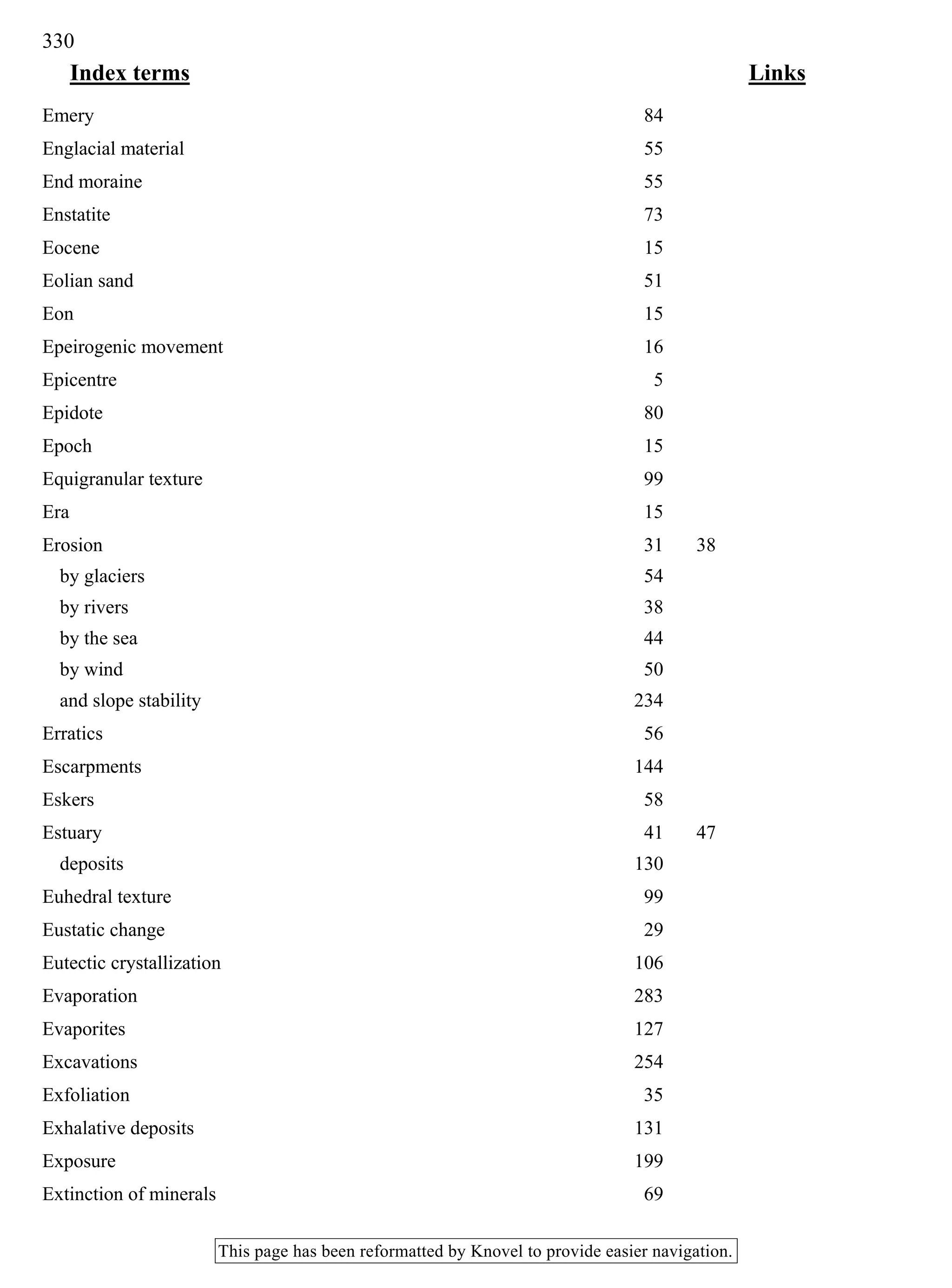

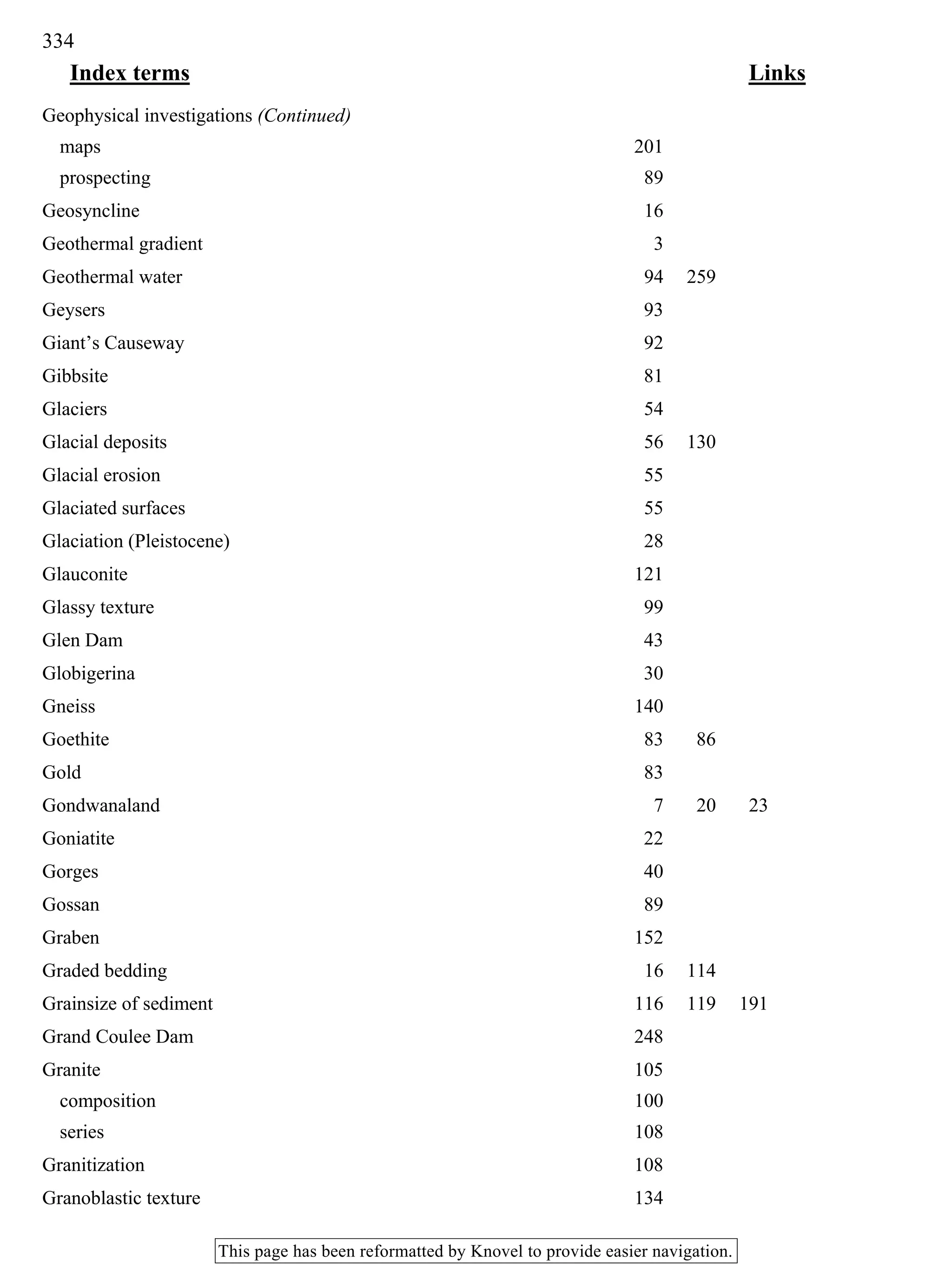

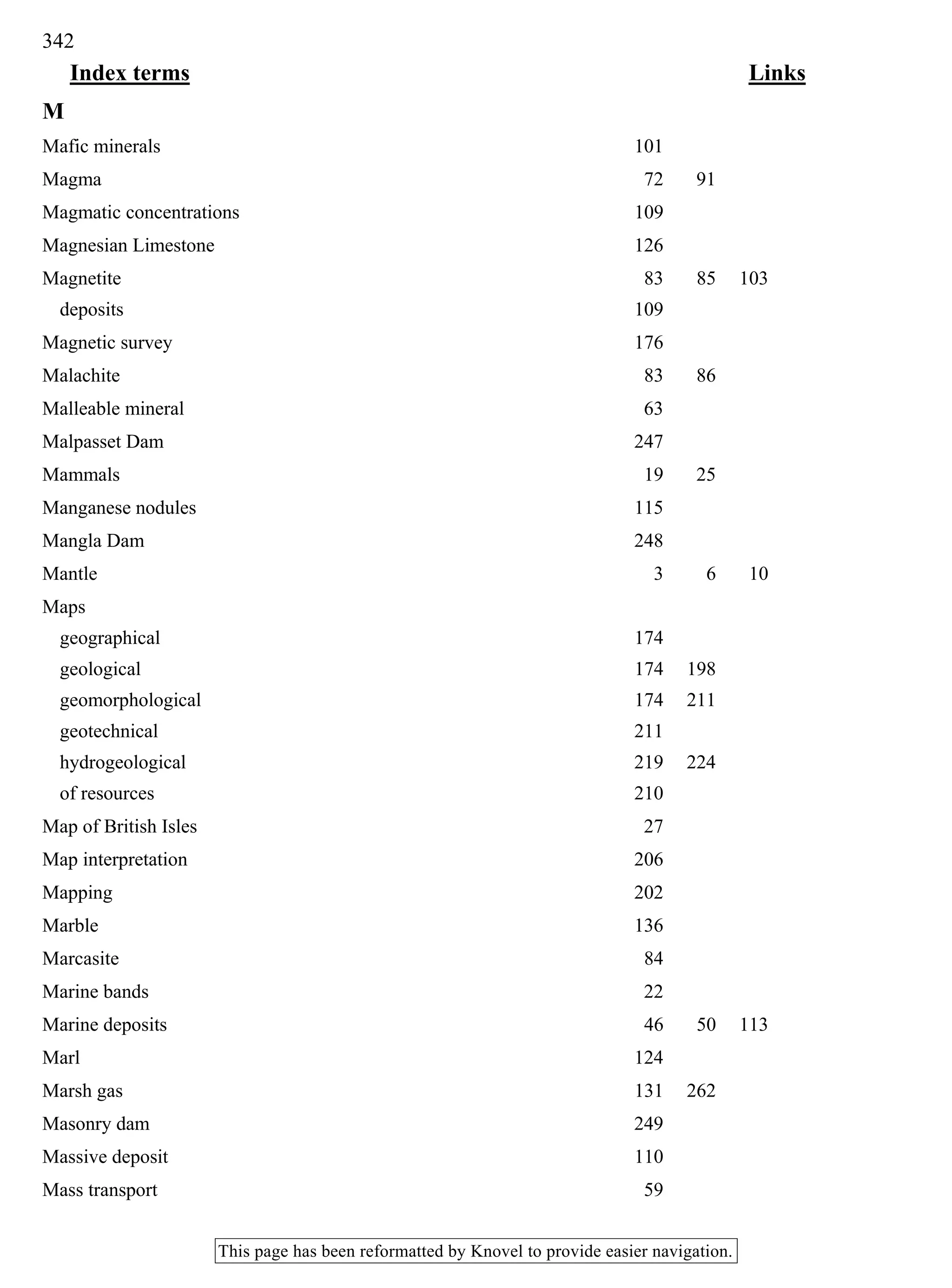

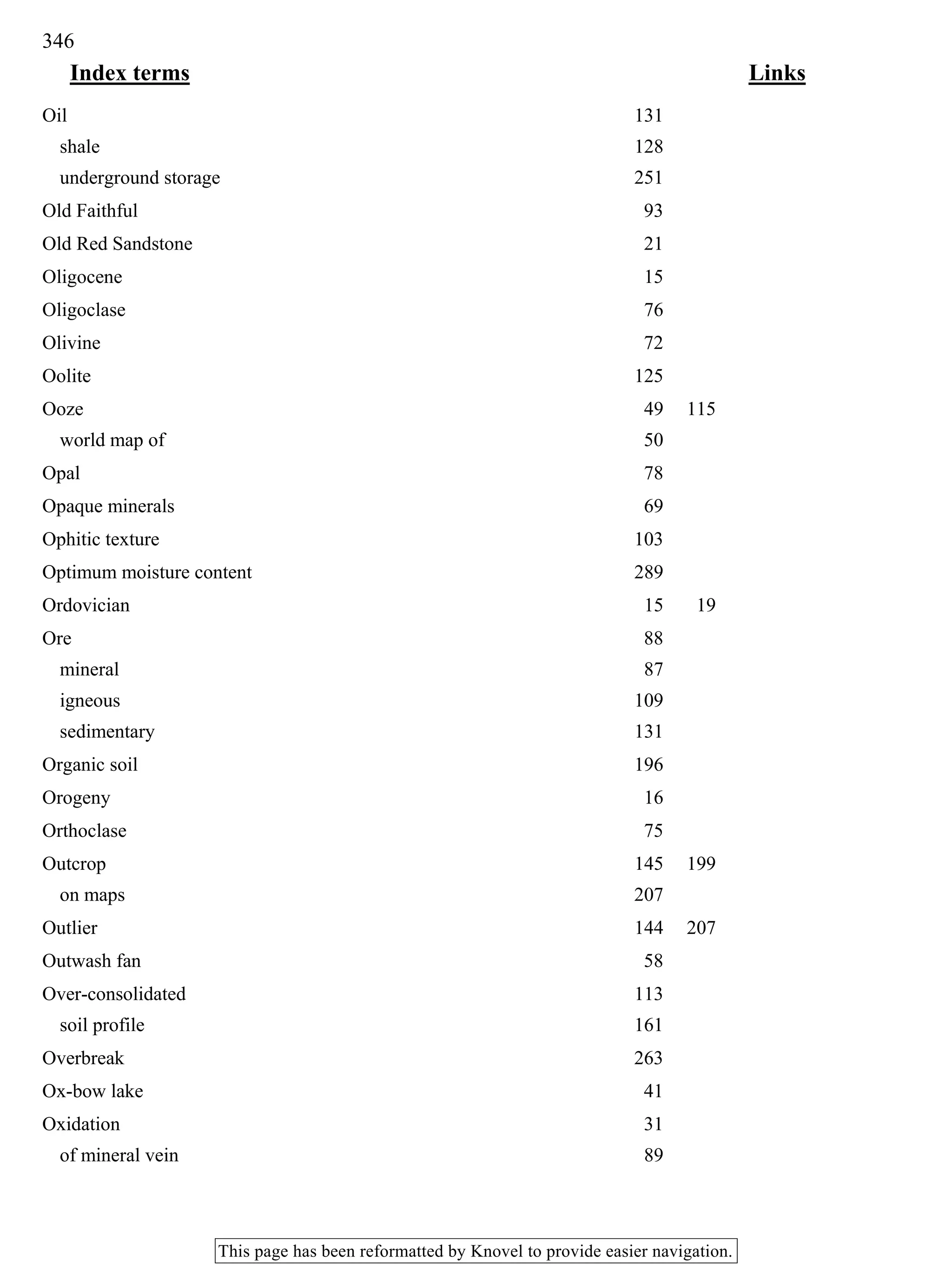

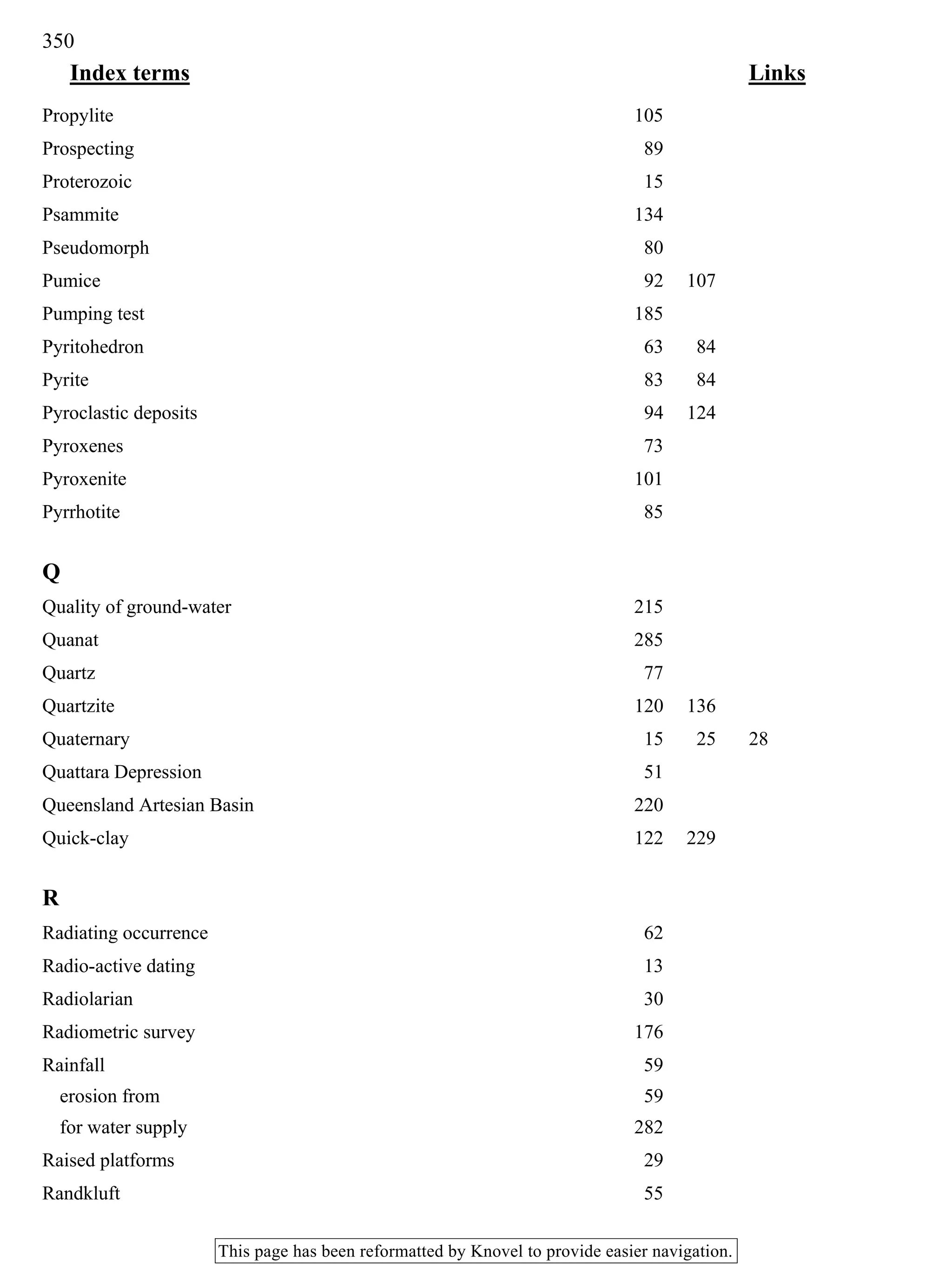

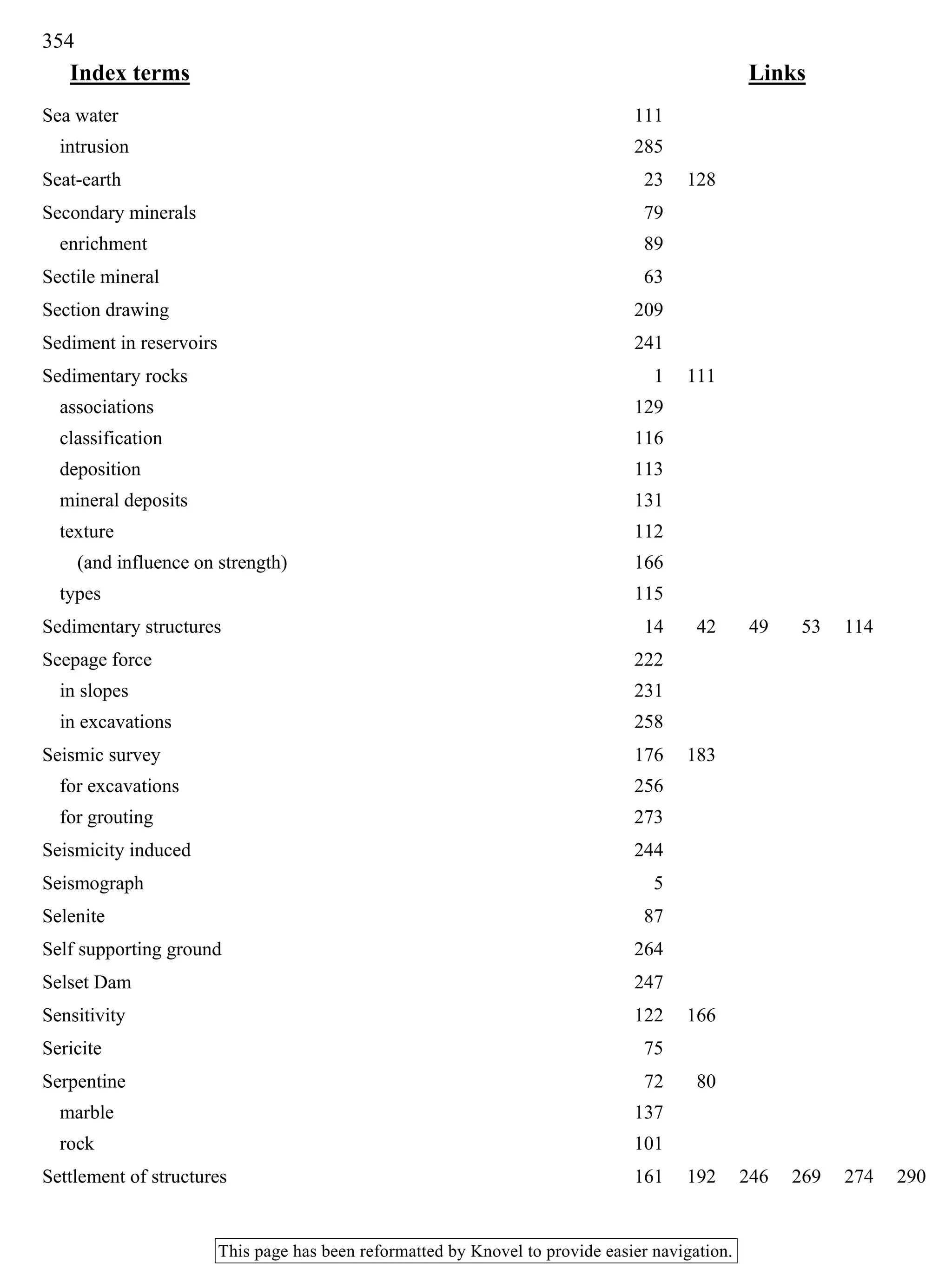

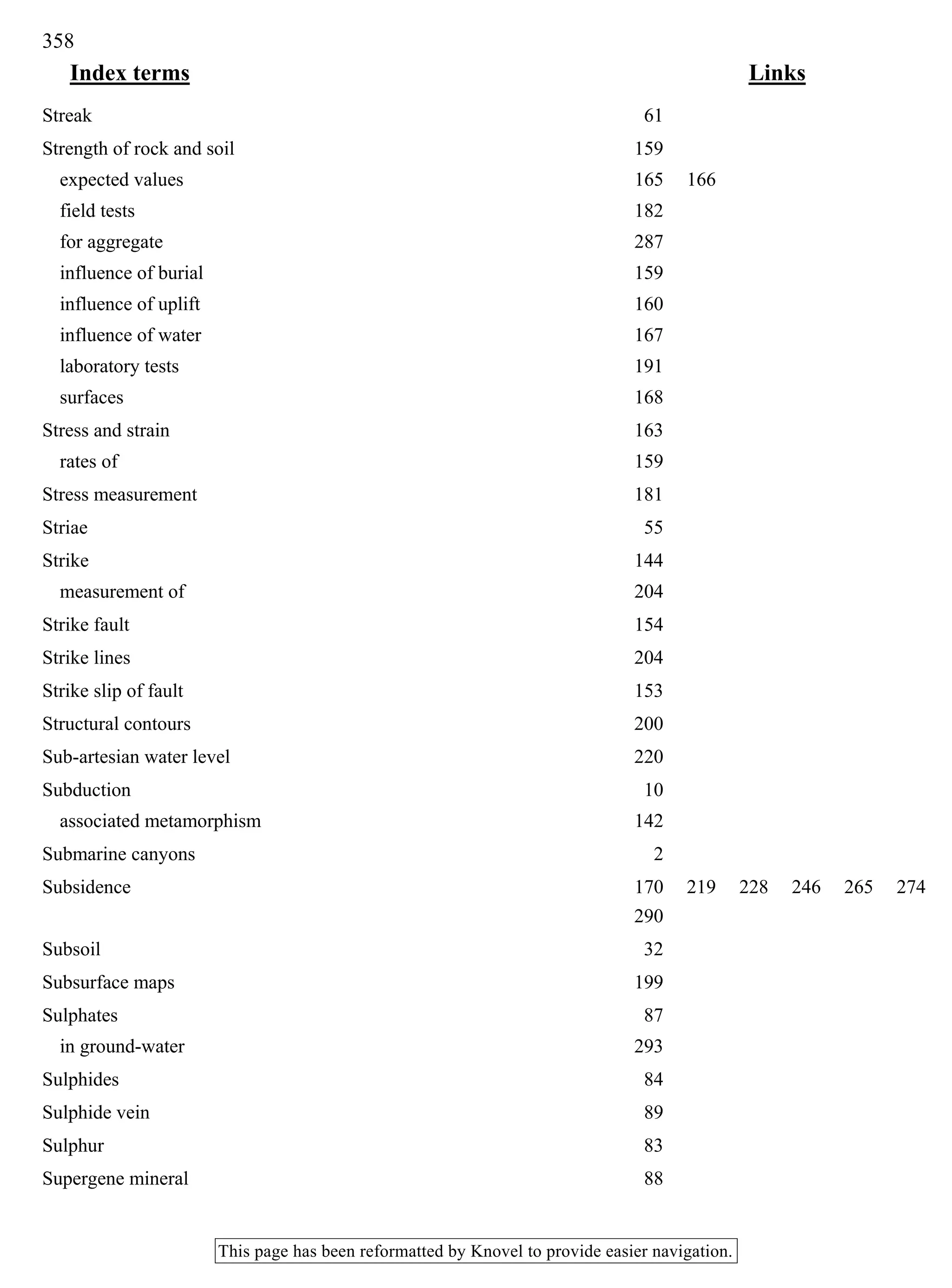

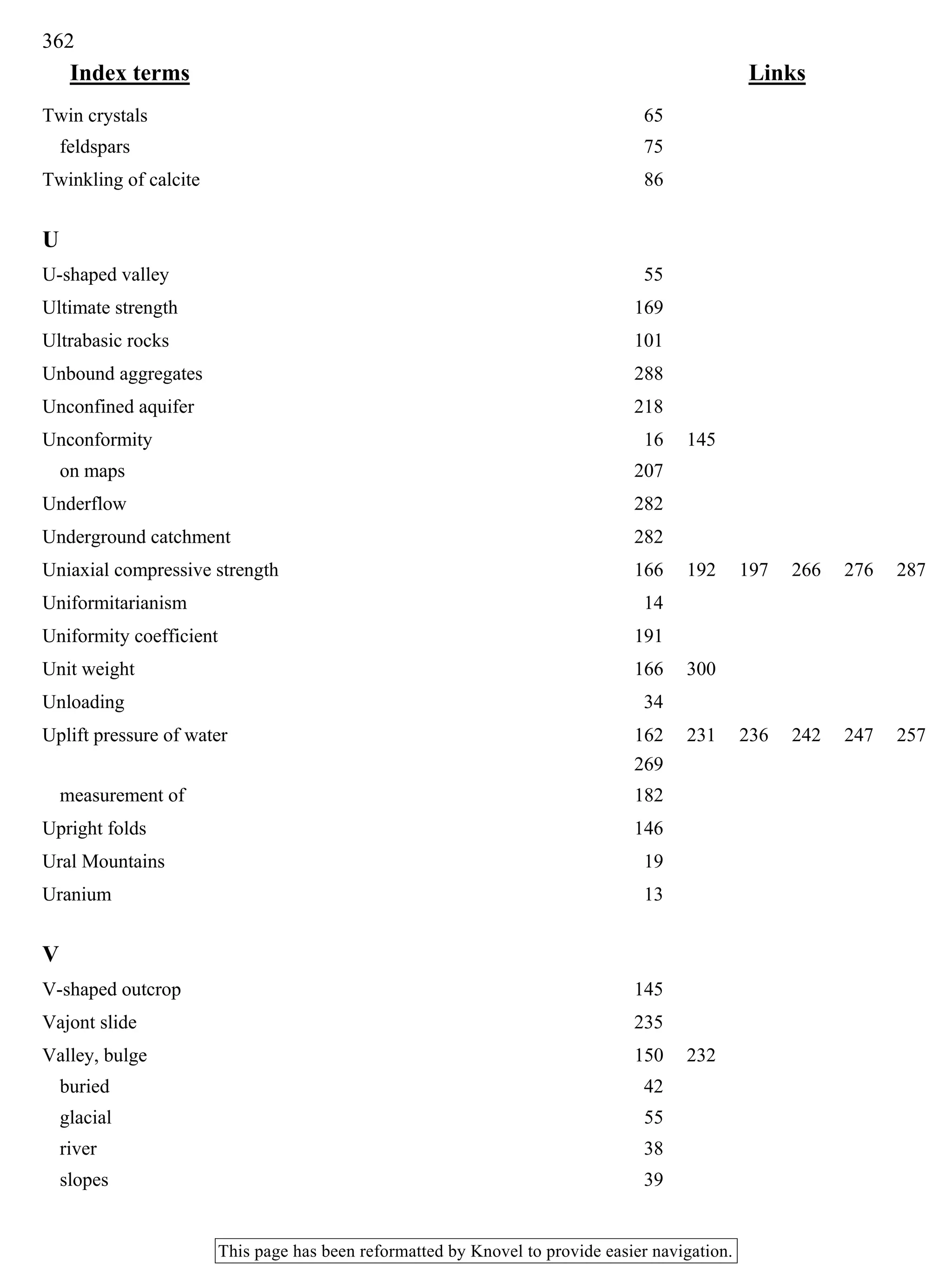

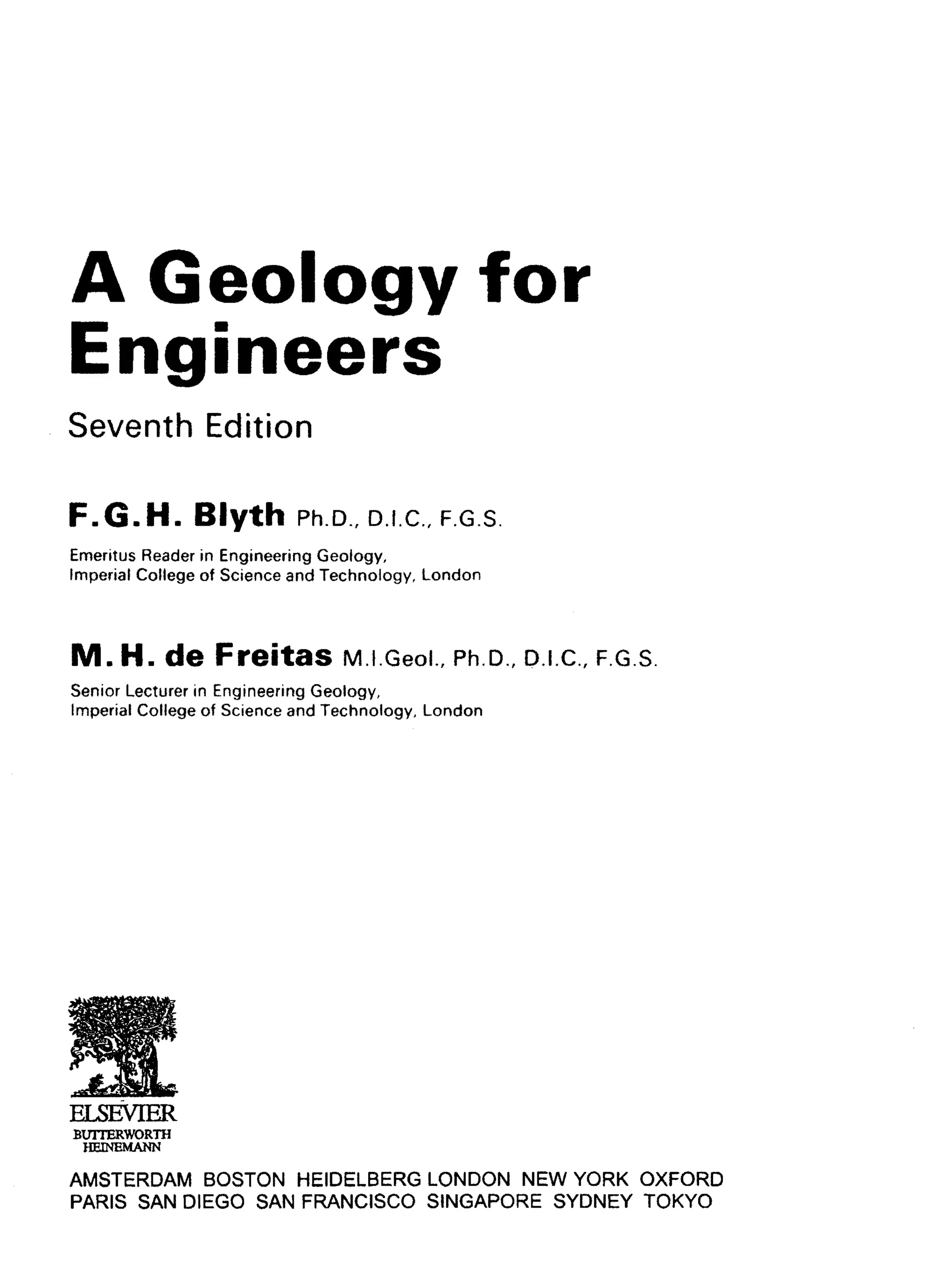

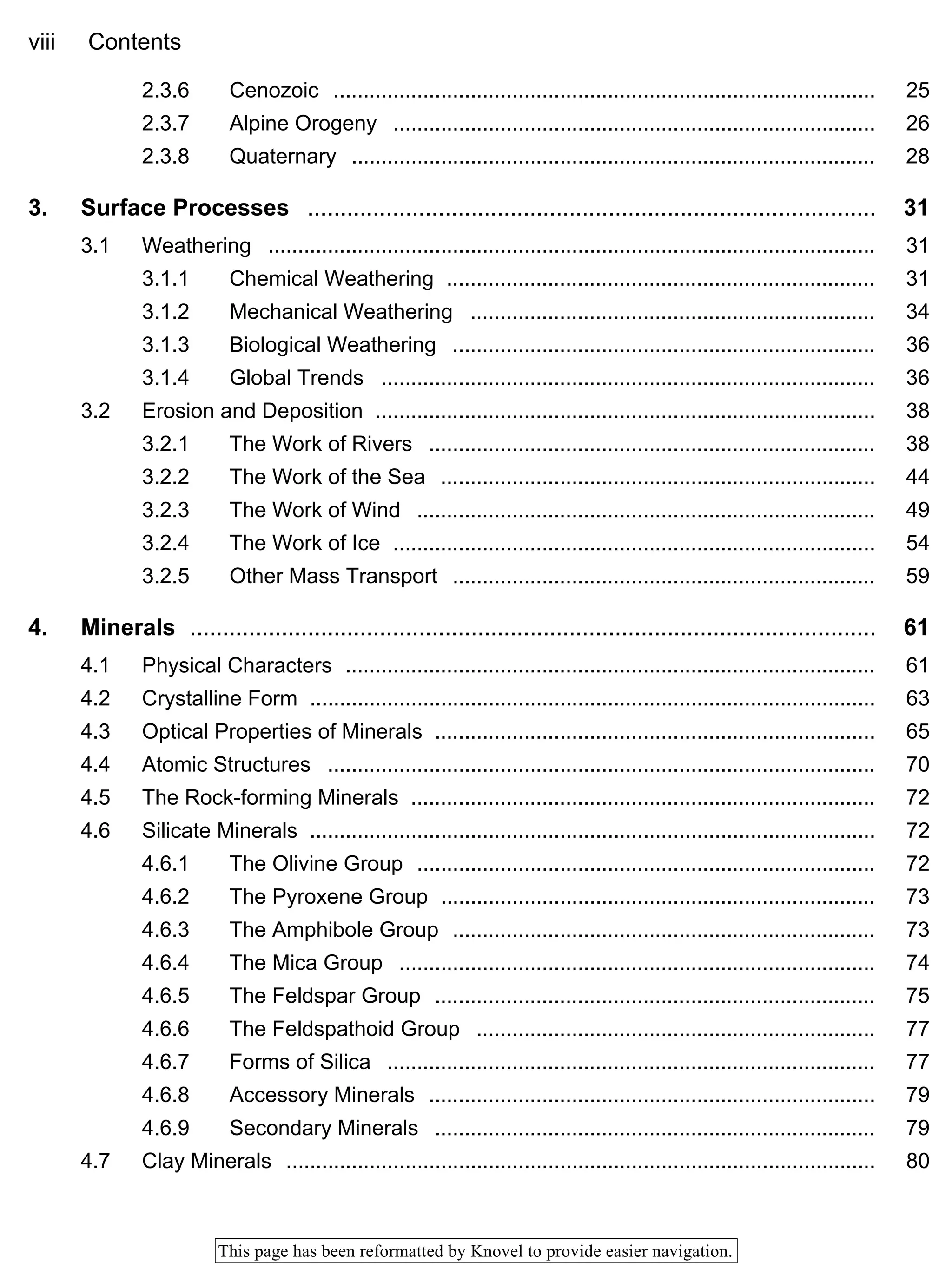

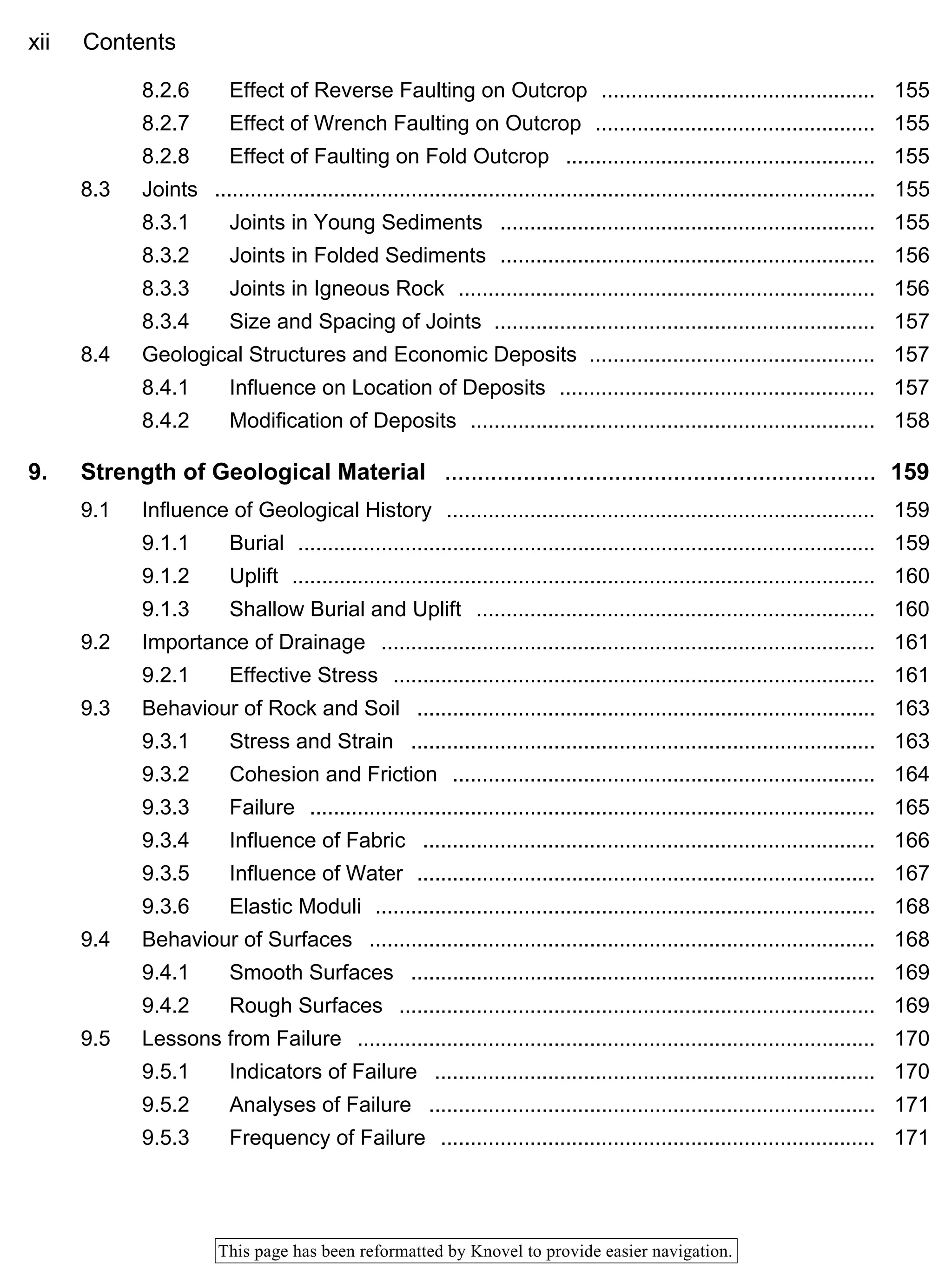

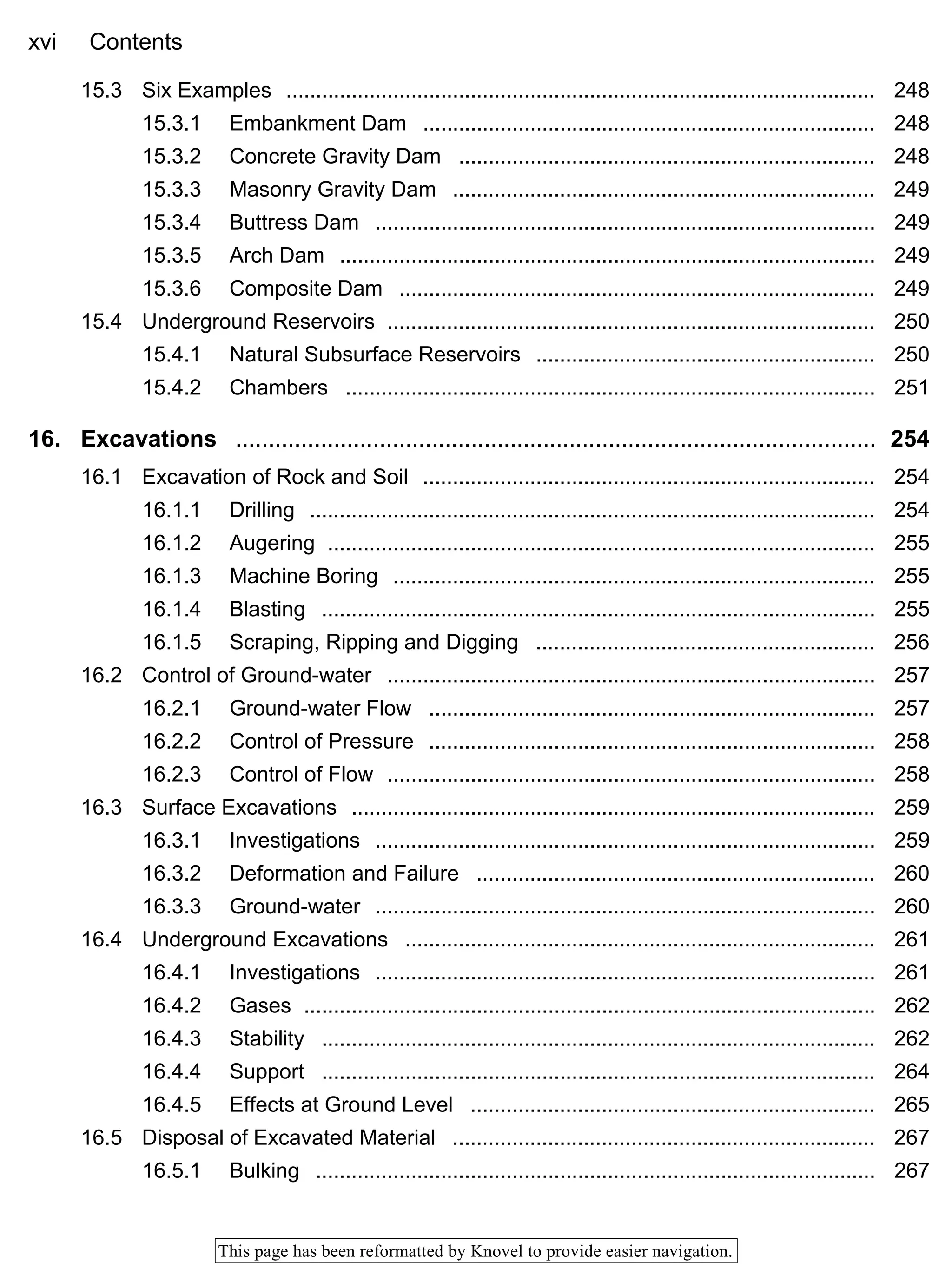

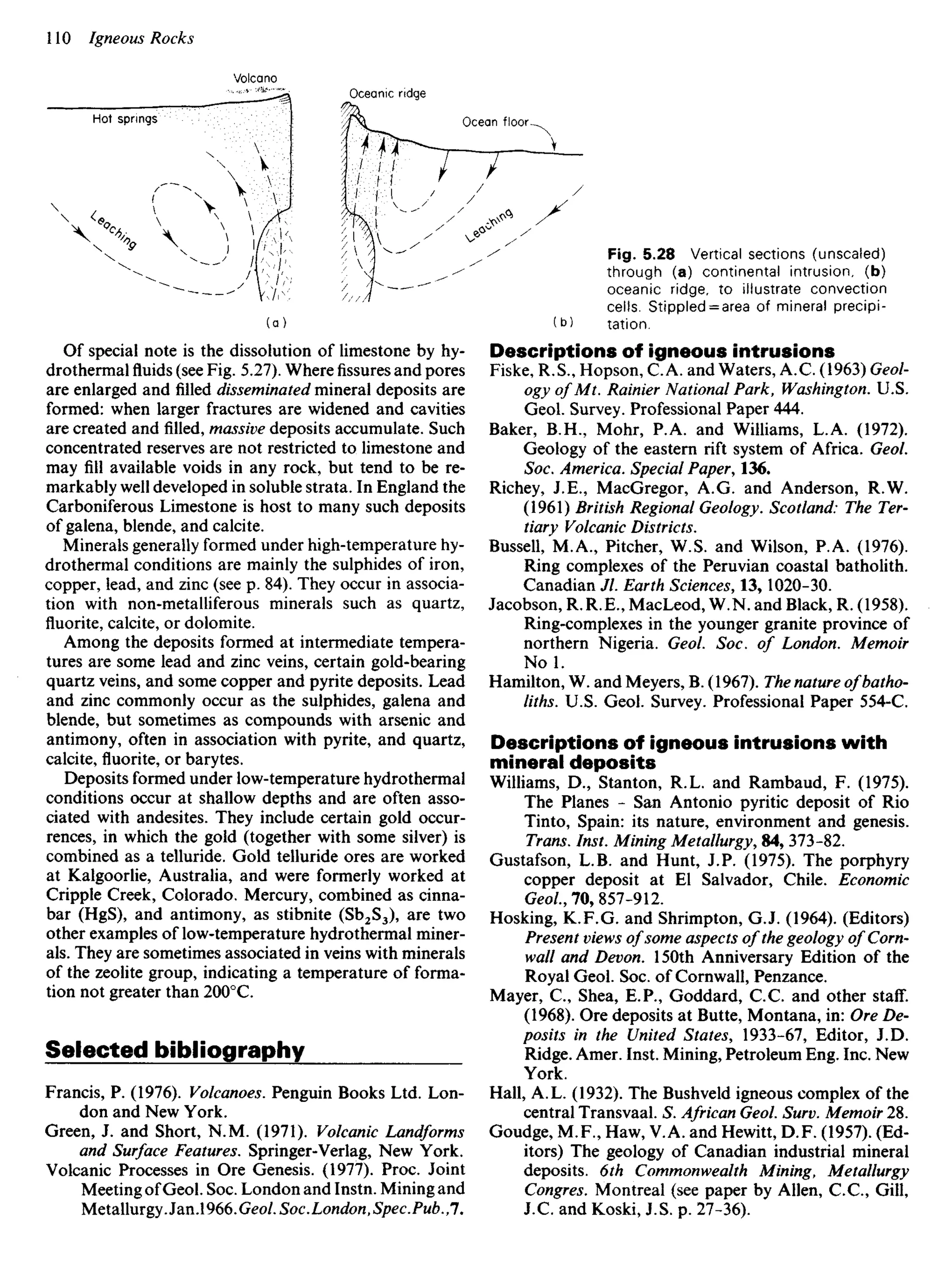

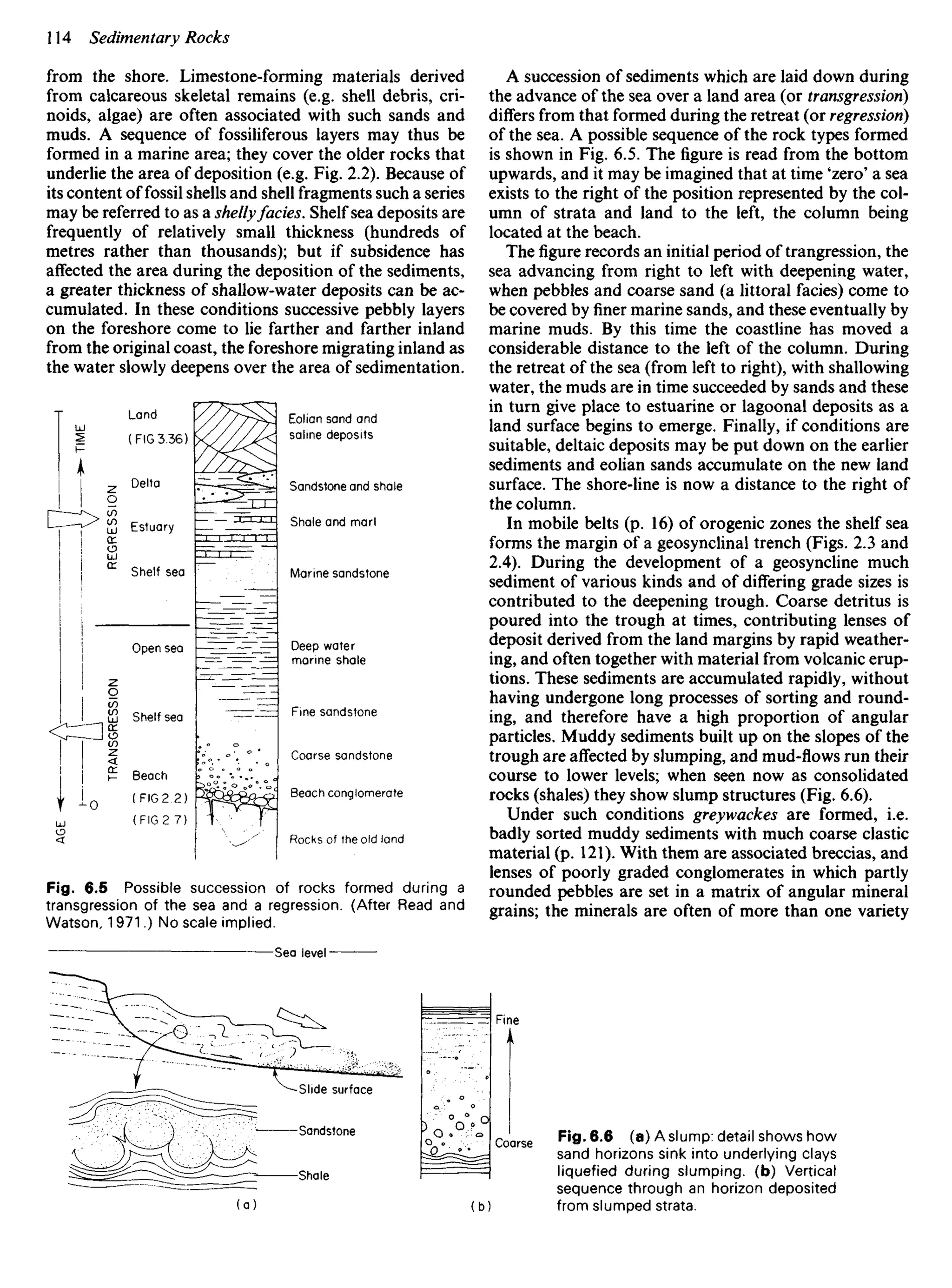

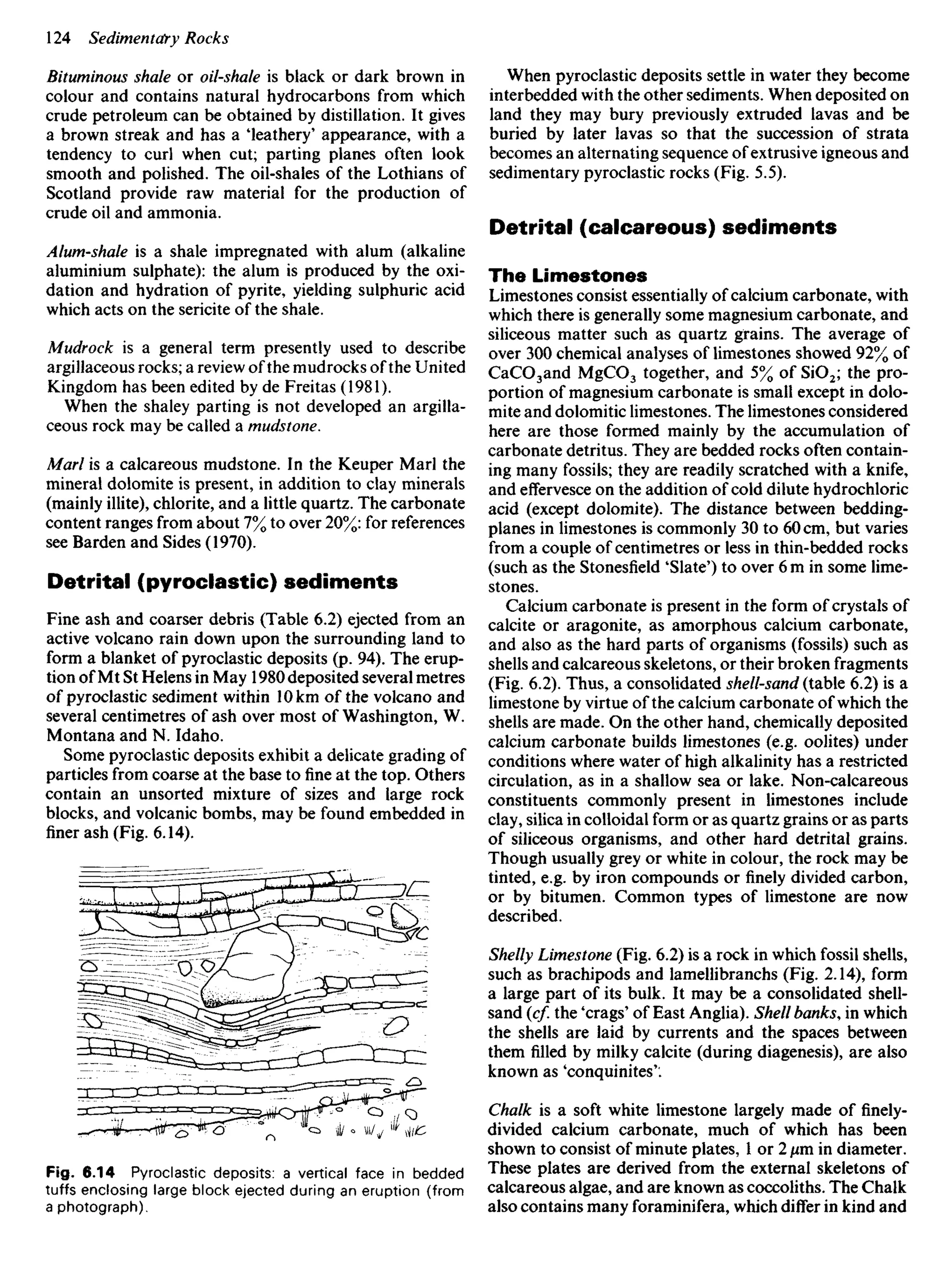

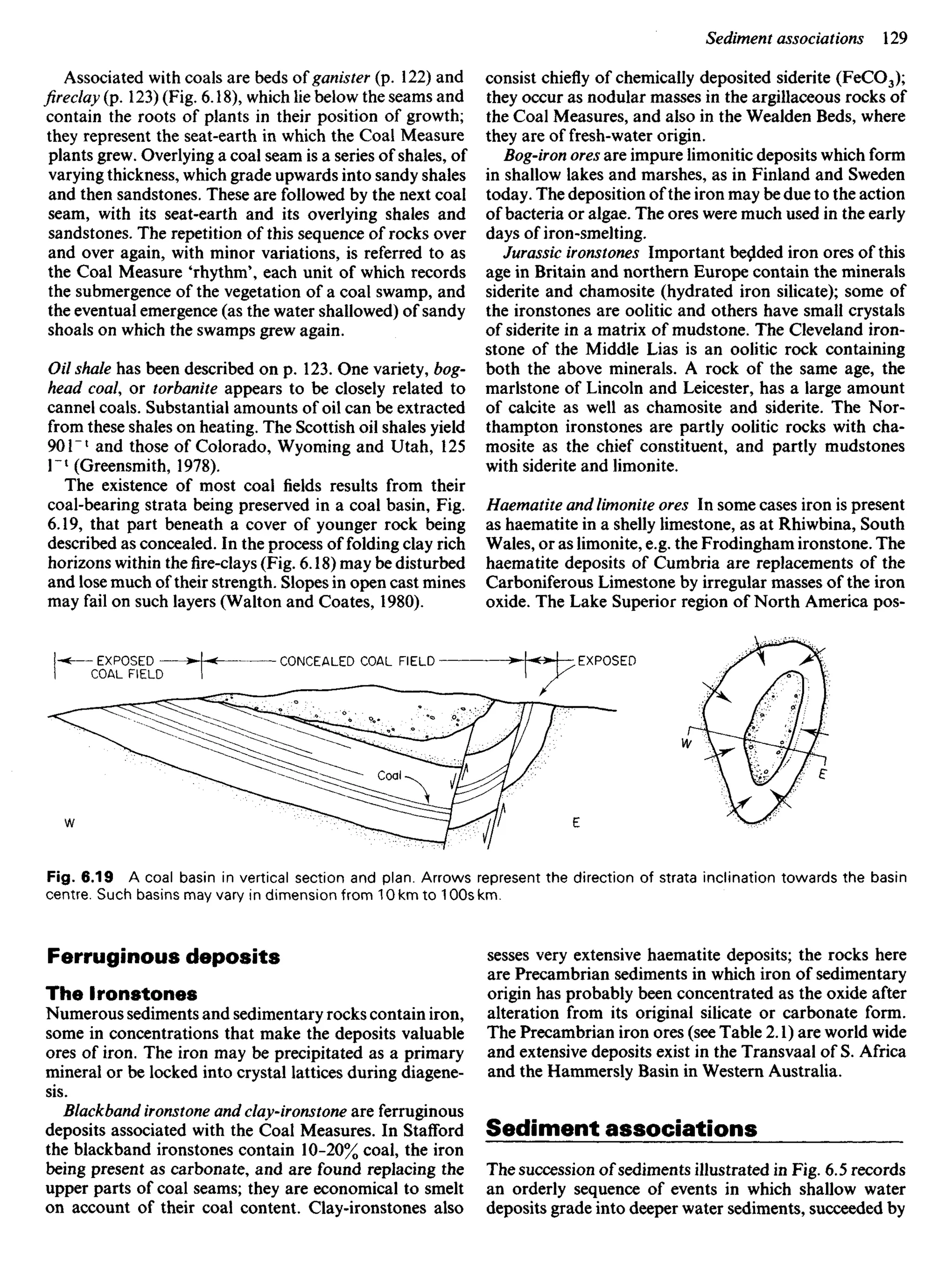

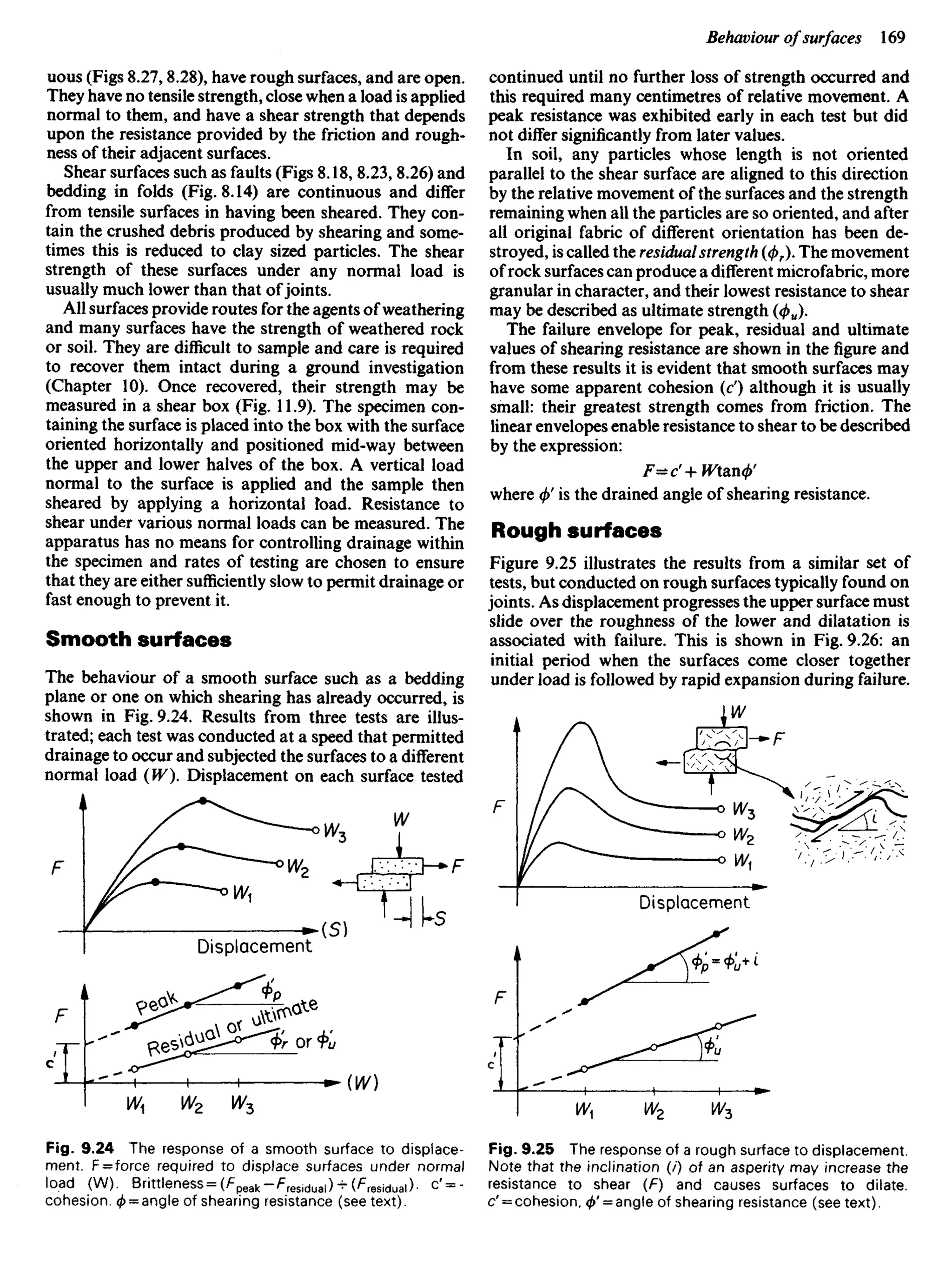

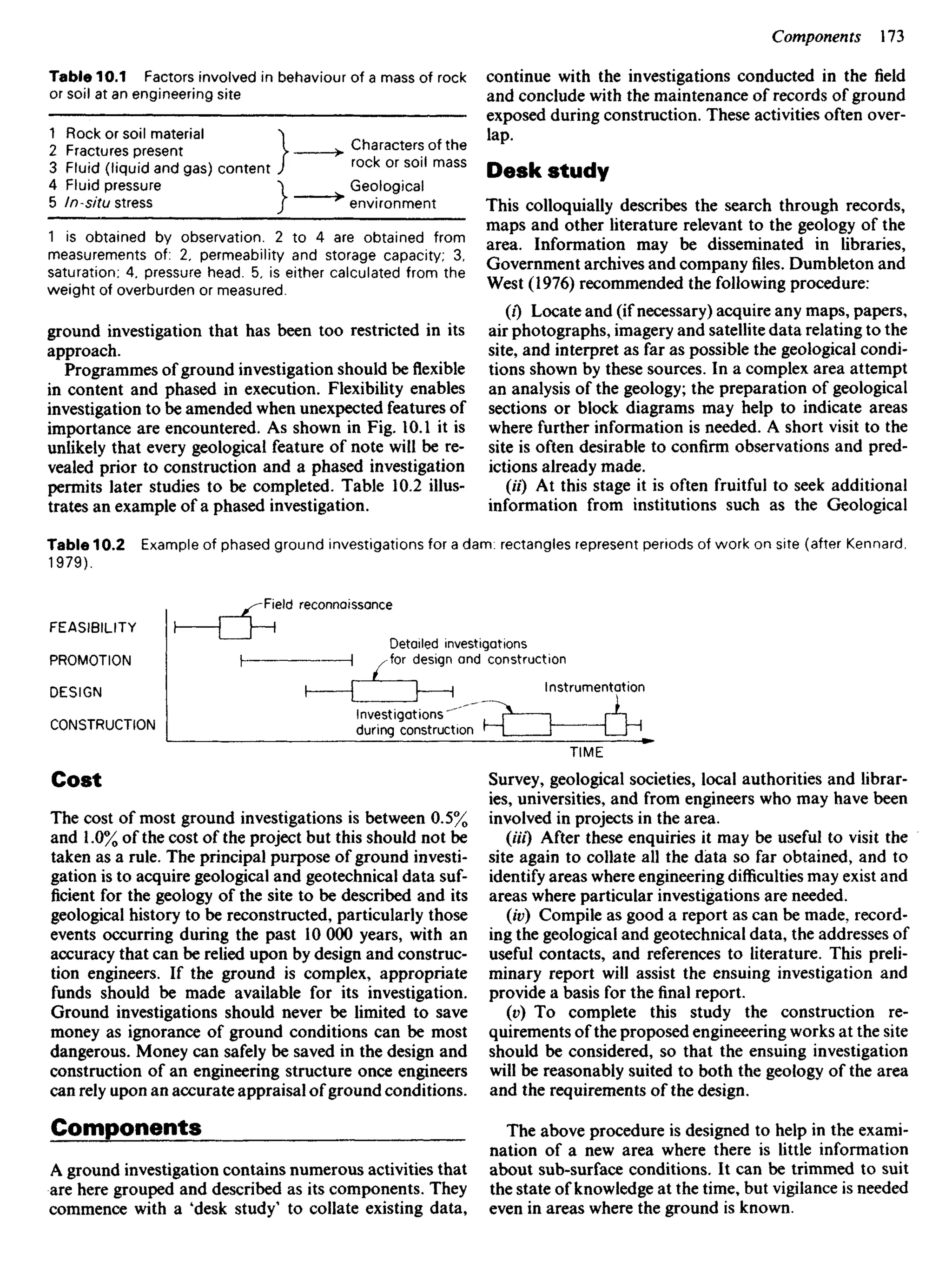

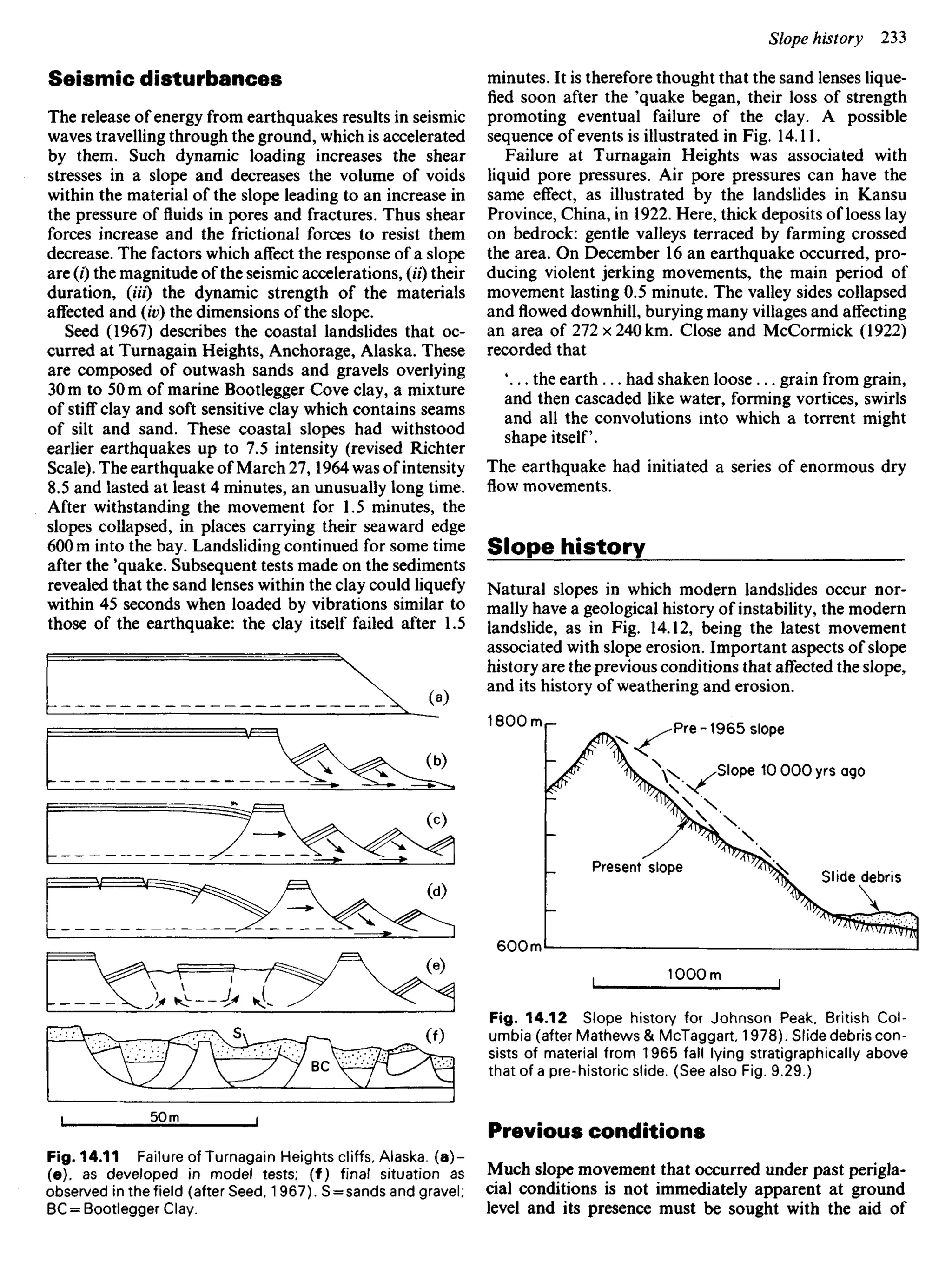

![Table 6.2 A classification for sediments and sedimentary rocks. Sediments listed in lighter print, sedimentary rocks in darker print.

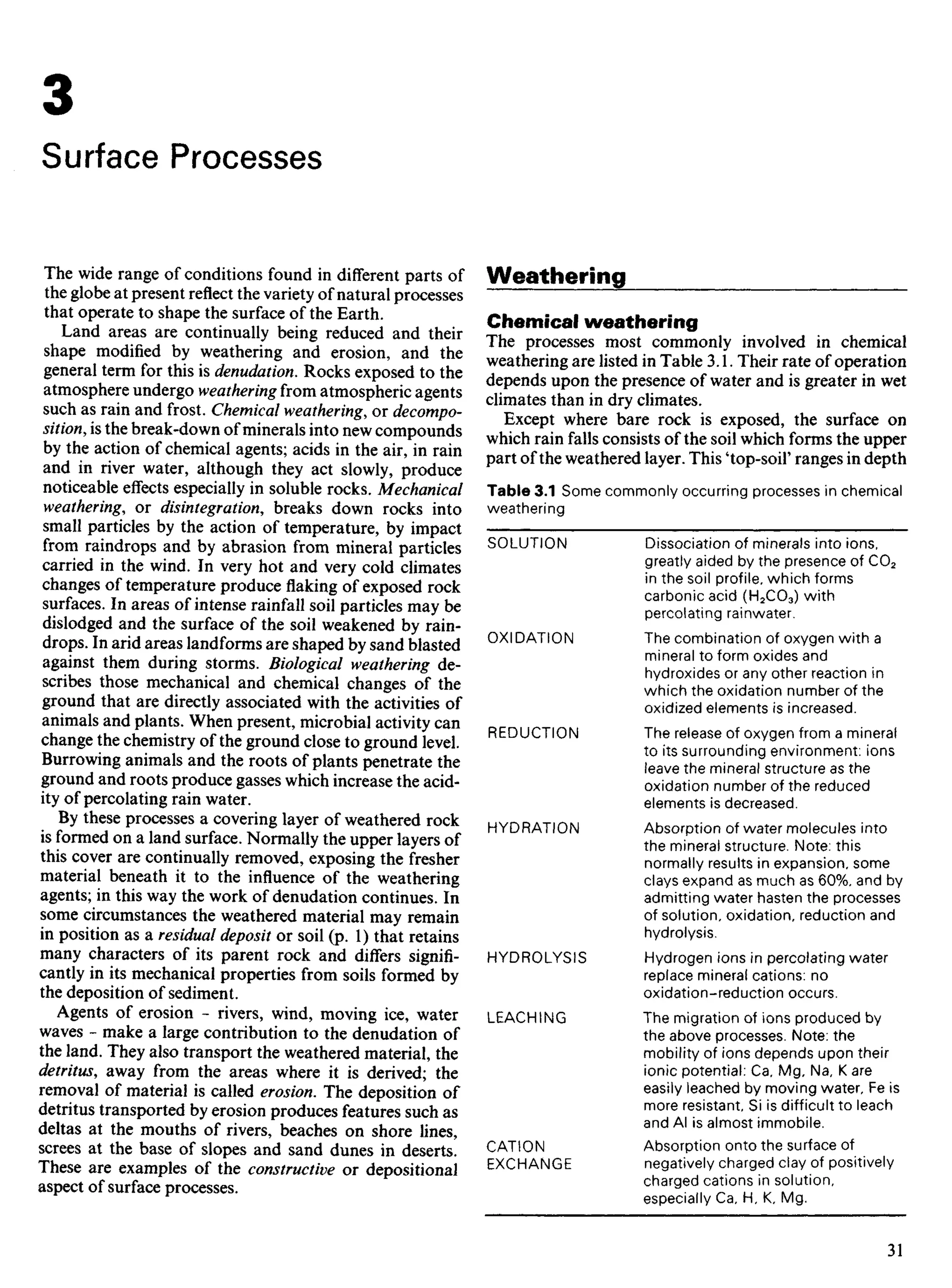

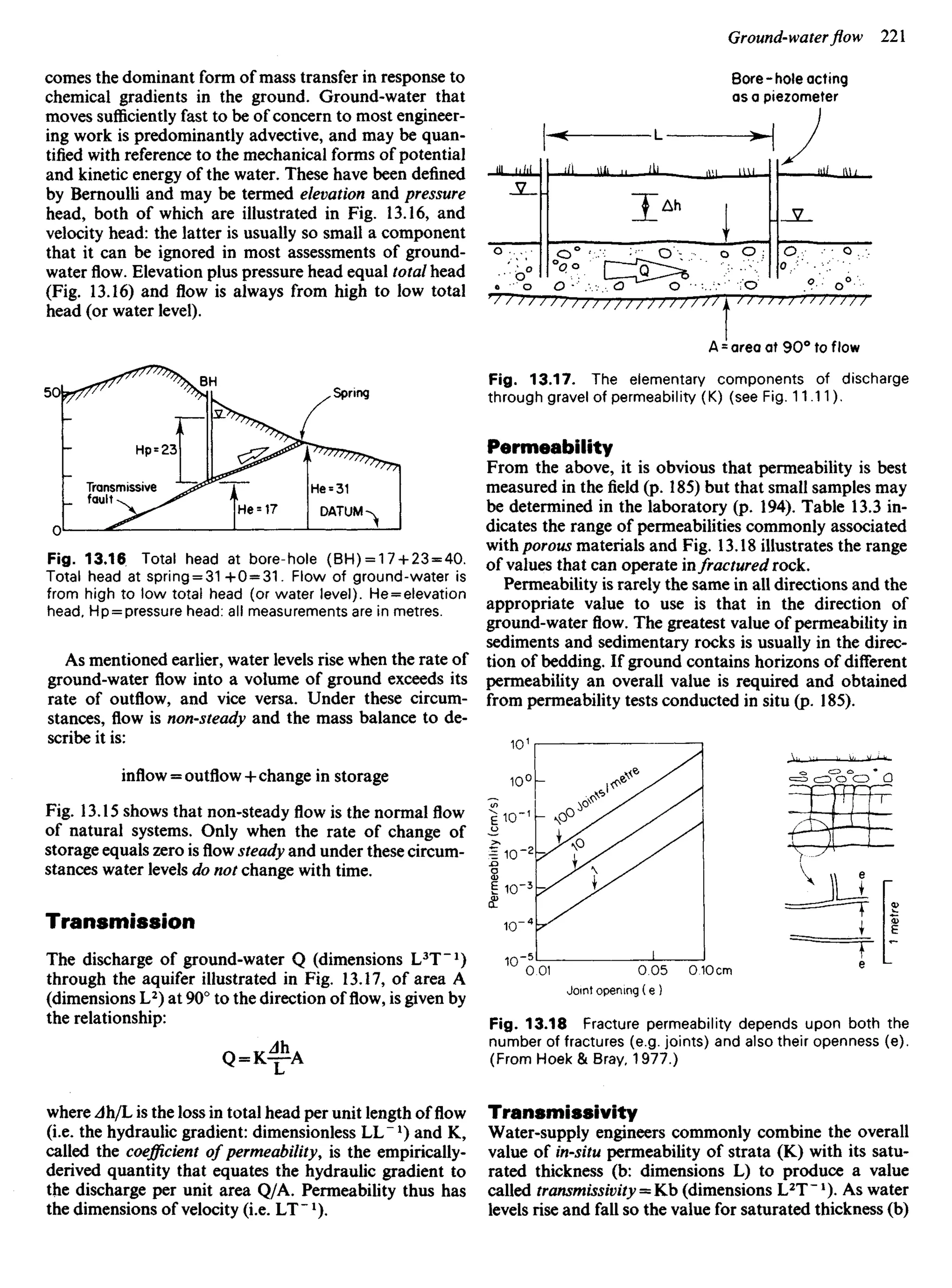

DETRITAL (pyroclastic)

>50% GRAINS OF VOLCANIC'ROCK

DETRITAL (calcareous)

>50% GRAINS OF CALCIUM CARBONATE

1

DETRITAL (terrigenous)

>50% GRAINS OF ROCK & SILICATE MINERALS

Consolidated

as rock

Unconsolidated

raw material

Consolidated

as rock

Unconsolidated

raw material

Consolidated

as rock

Geological

Term

Unconsolidated

raw material

PARTICLES

(orGRAINS)

size

(mm) name

Agglomerate

Volcanic

breccia

X

Tuff

Volcanic bombs &

ejected rock blocks

Fine strands and

droplets of lava

ejected into the

atmosphere

Volcanic ash

Volcanic dust

Conglomerate

Breccia

LU

CJ

Carbonate <

gravel u

Pisolithic c

grit 5

Carbonate "§

grit *

O

CJ

Carbonate H

sand cj z

..^. _l LU

oolitic < Q:

limestone u

<

Carbonate ^,

silts t

Z)

Loess 5

Cement-stone d

Chalk cj

Storm beaten

Colluvium

Coral reef debris

—i Carbonate

> gravel: eg. coral reef

Q£ debris.

O Shell rich beach

! gravel

it

^ Carbonate

< sand. eg. shelf and

^ beach

T

^] Carbonate

Zn Silt: eg. lagoon silt

• Desert Dust

>. Carbonate

-J mud

Comglomerate

Breccia

Tillite

Conglomerate

Grit

Sandstone

(arkose, grey-

wacke, and

other varieties)

Loess

Siltstone

Mudstone &

Shale

E

CO ȣ=

LU y

II

< CO

ZD ^

<cj I

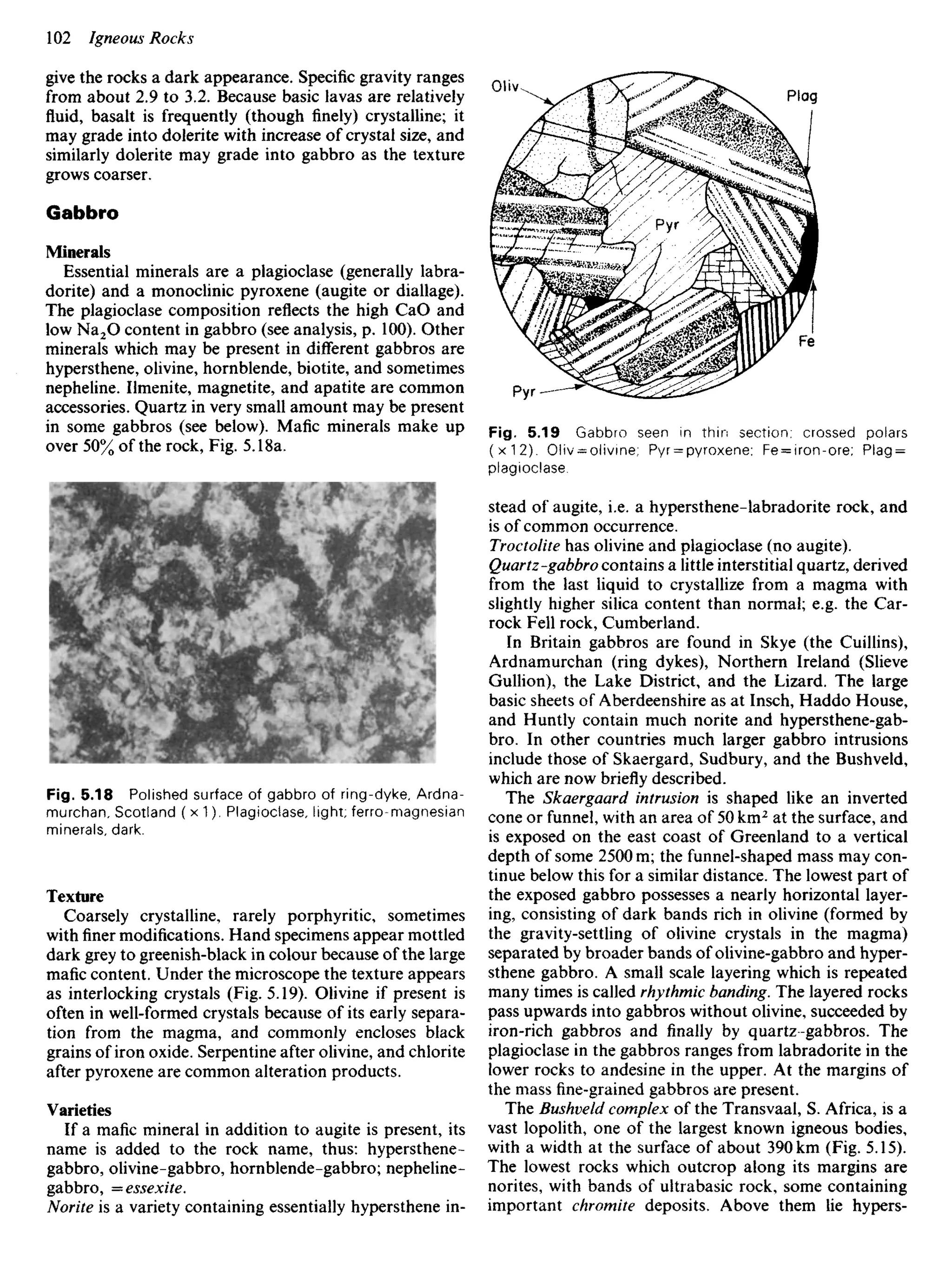

CO "co

O .E

CC

<

Storm beach

Colluvium (scree,

or talus)

Glacial boulder beds

1

Coarse-alluvium

(e.g. wadi)

LU

<

QC

Fine-alluvium

— — Deltaic grits

^ and sands

Z

<

1 Sand beach

-X- Desert sand

f & dust

-i Estuarine

00

silt

j_ Glacial silts

T & clays

-i clay

CJ

I ooze

Boulder

Cobble

Pebble

Granule

Sand

Silt

Clay

200

4

2 _

0.002](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ageologyforengineersseventhedition-240123054612-a0c16209/75/A_Geology_for_Engineers_Seventh_Edition-pdf-100-2048.jpg)

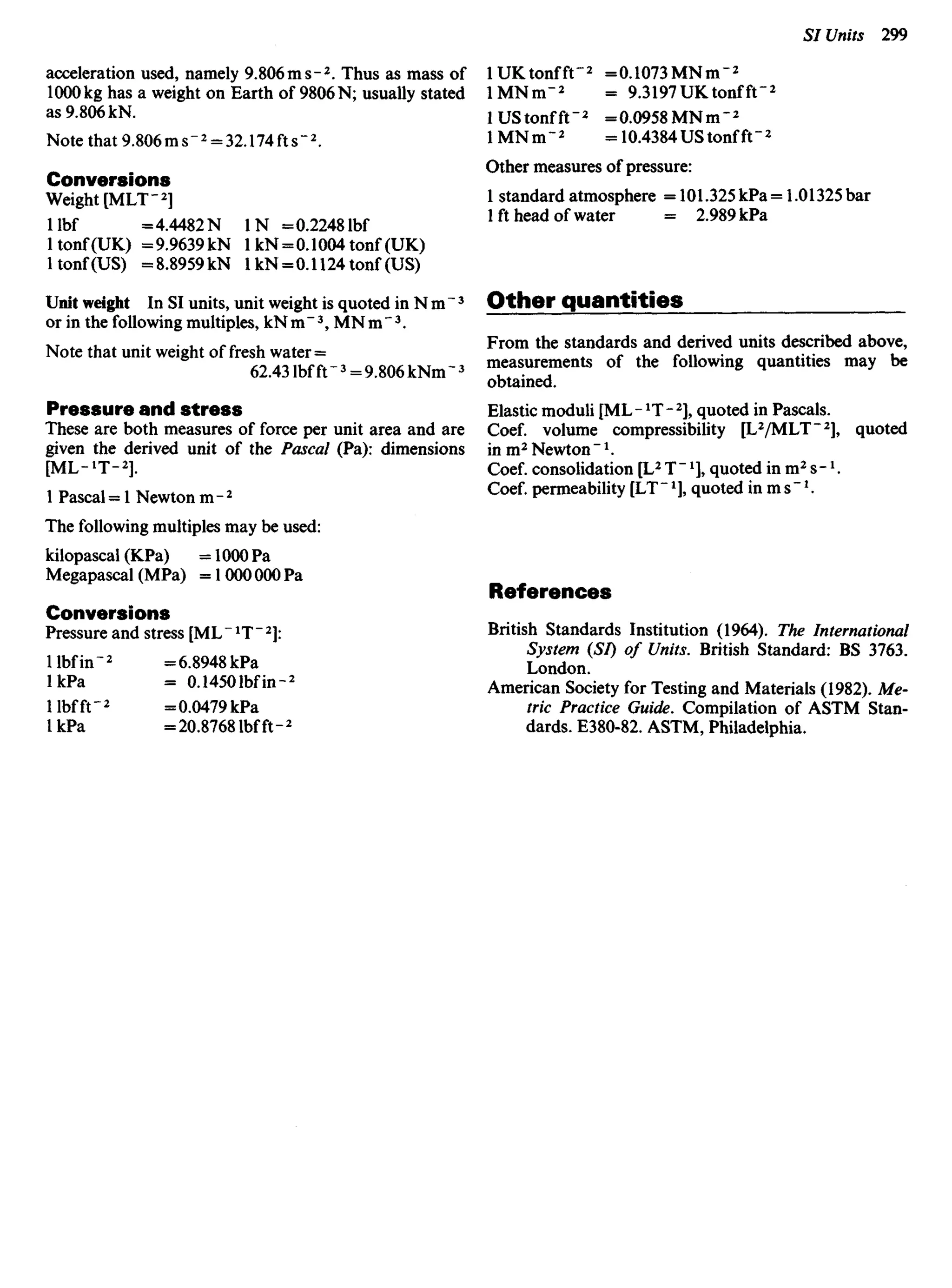

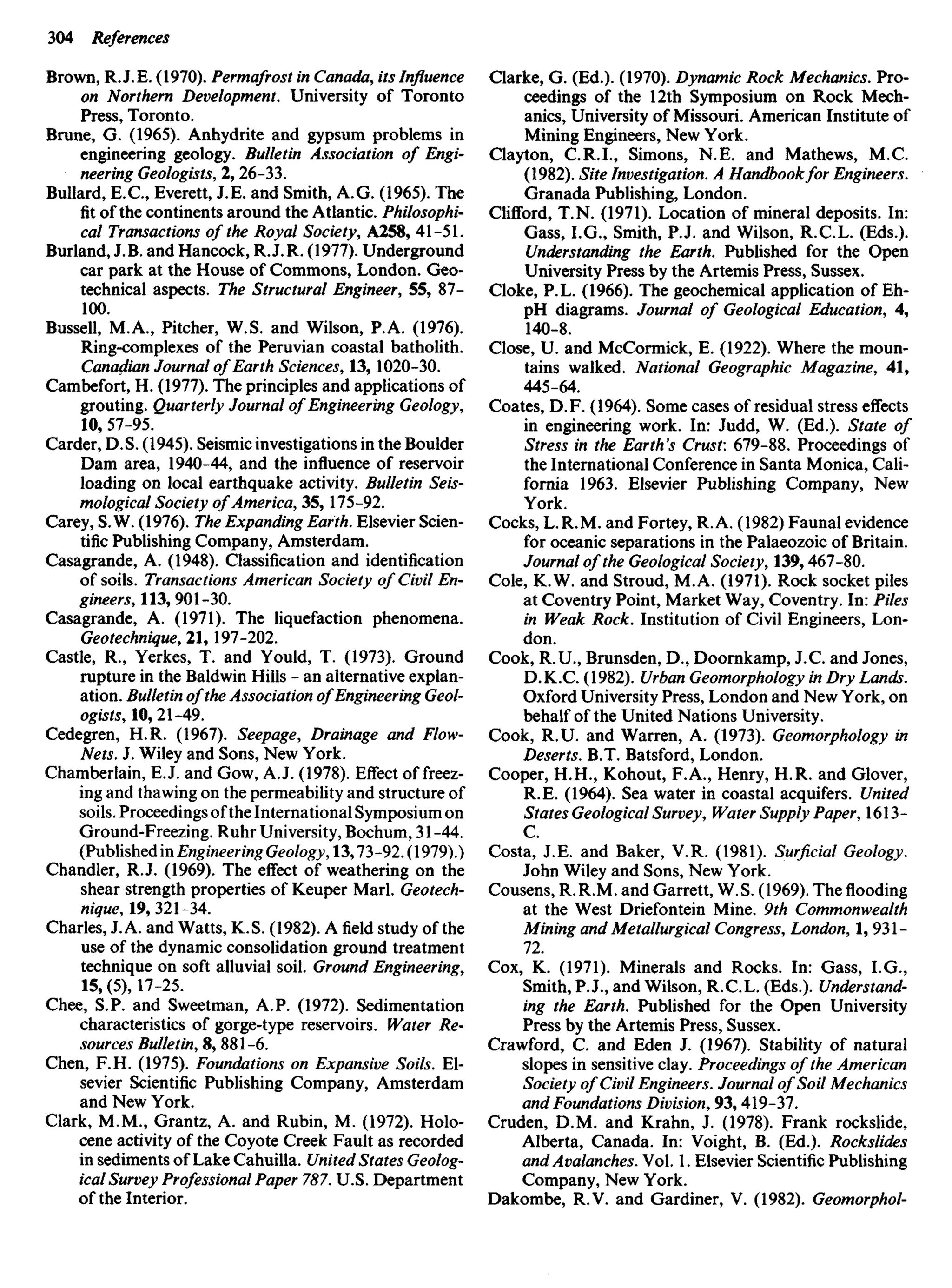

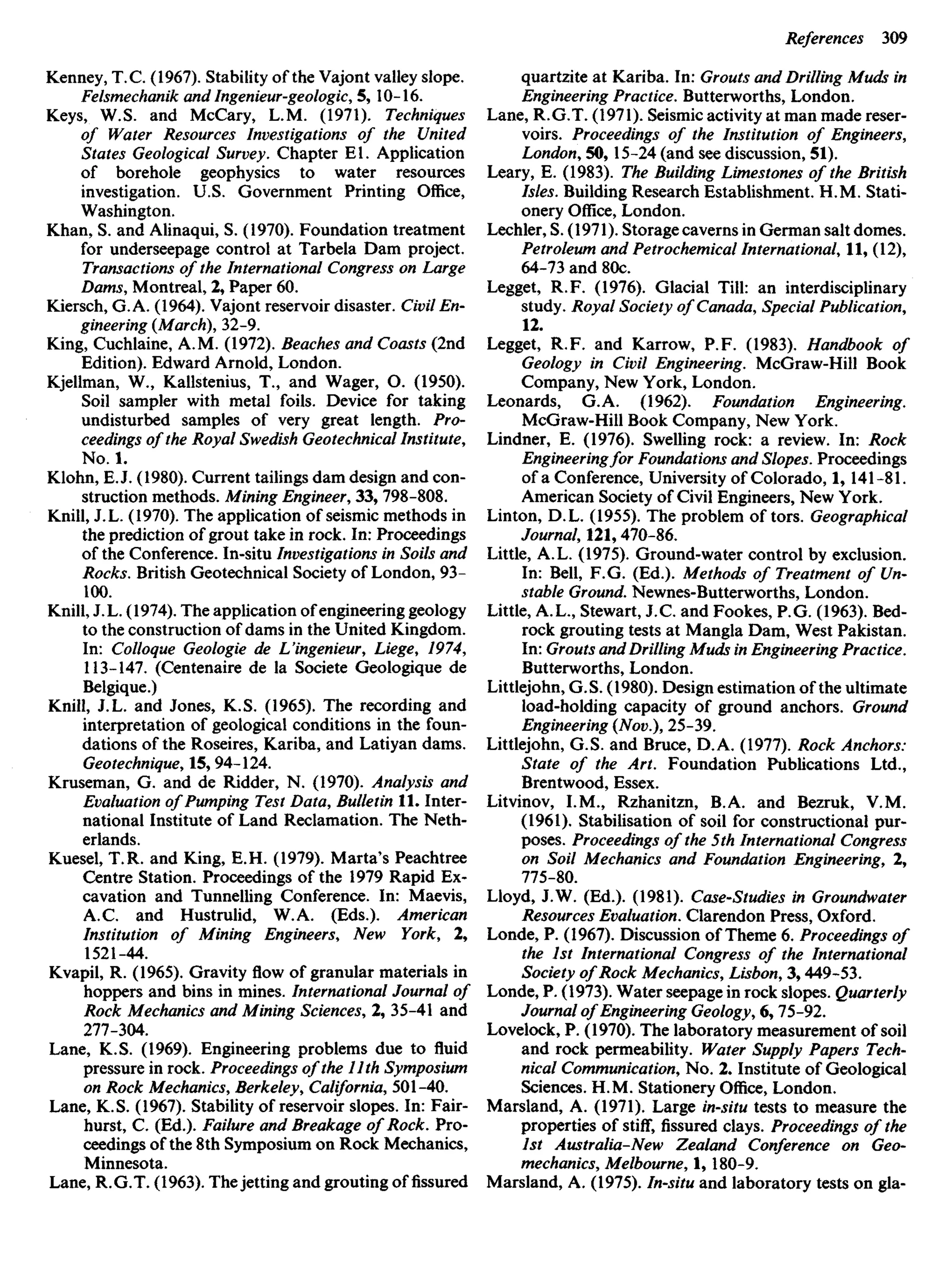

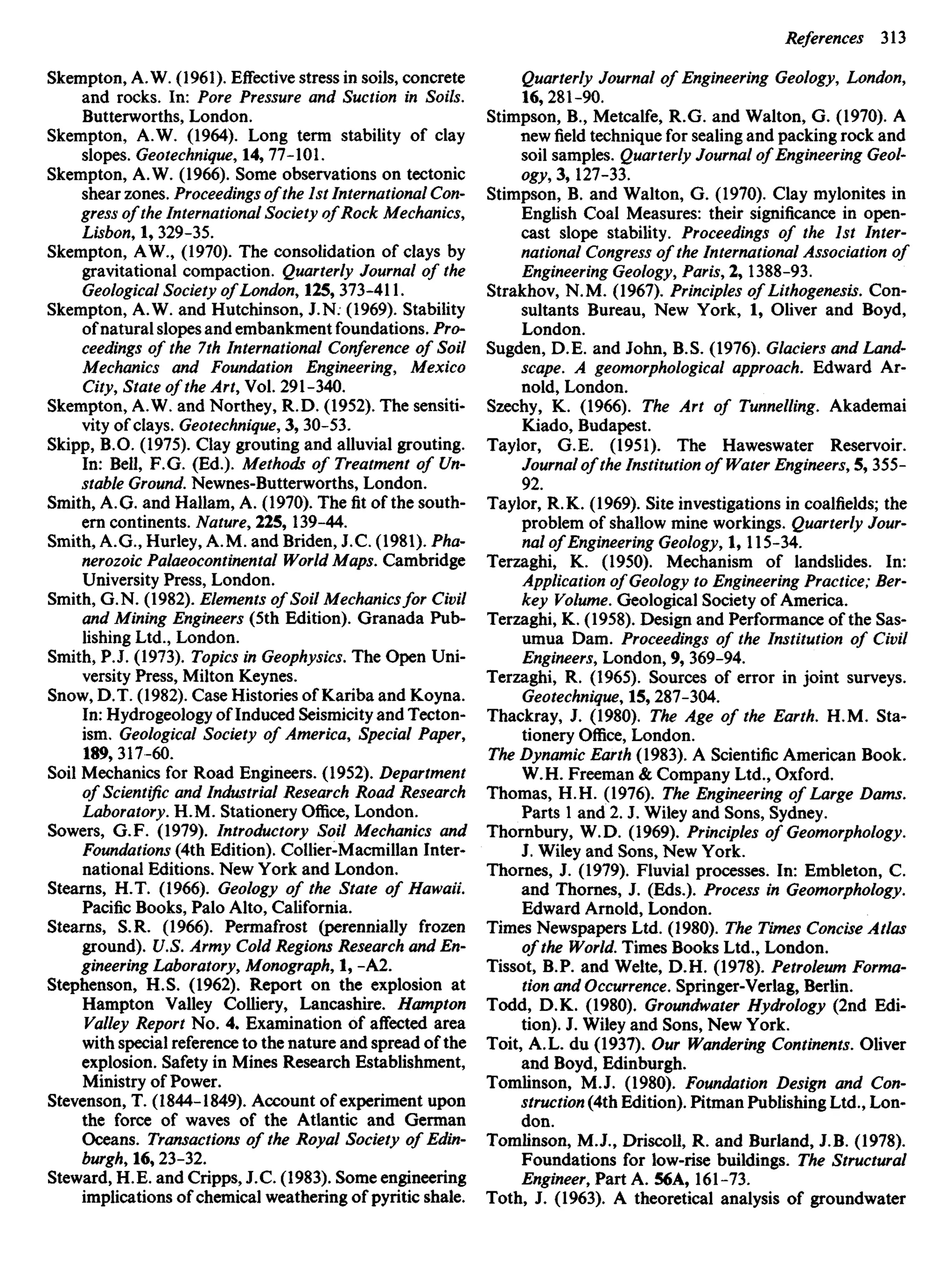

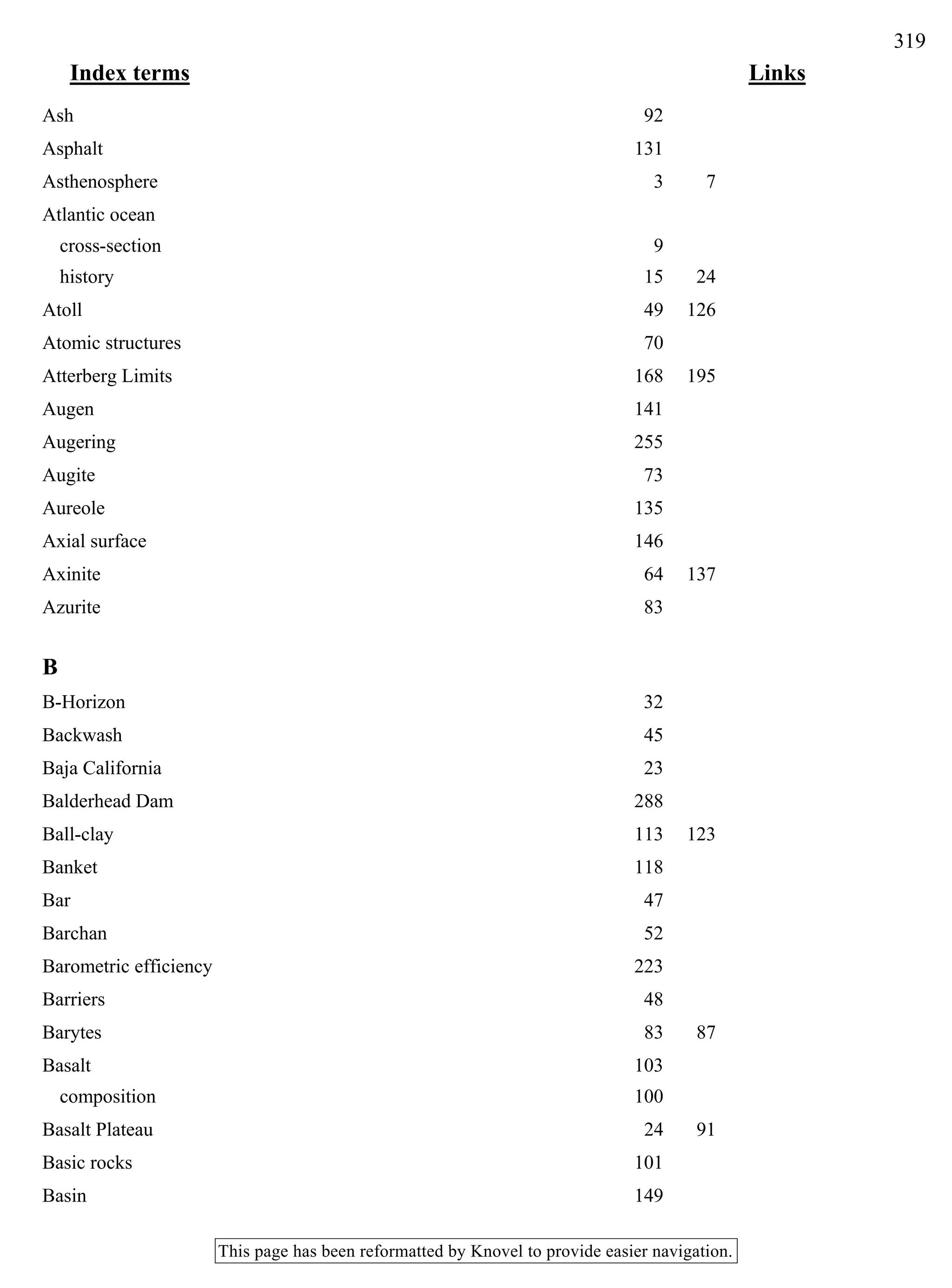

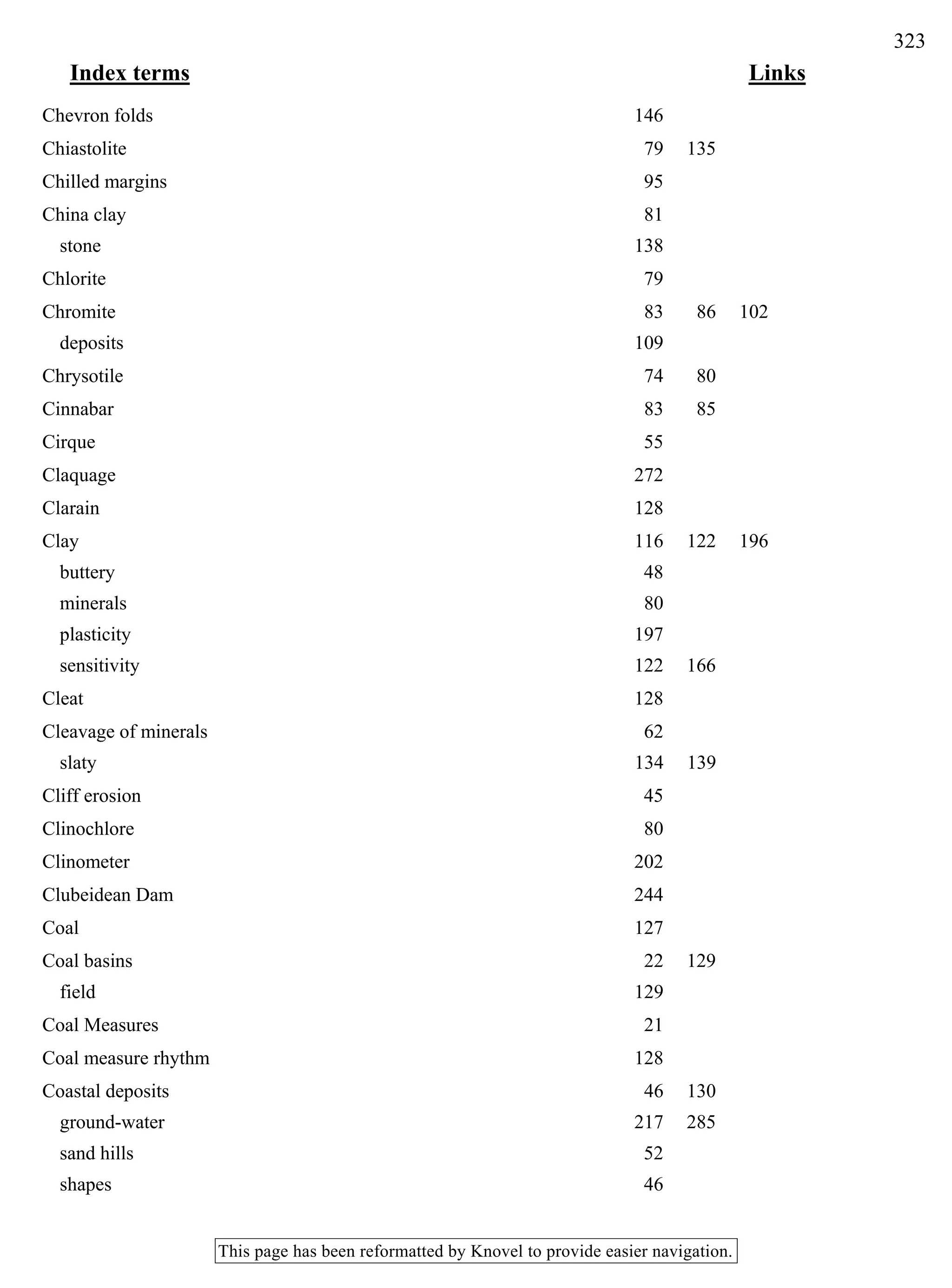

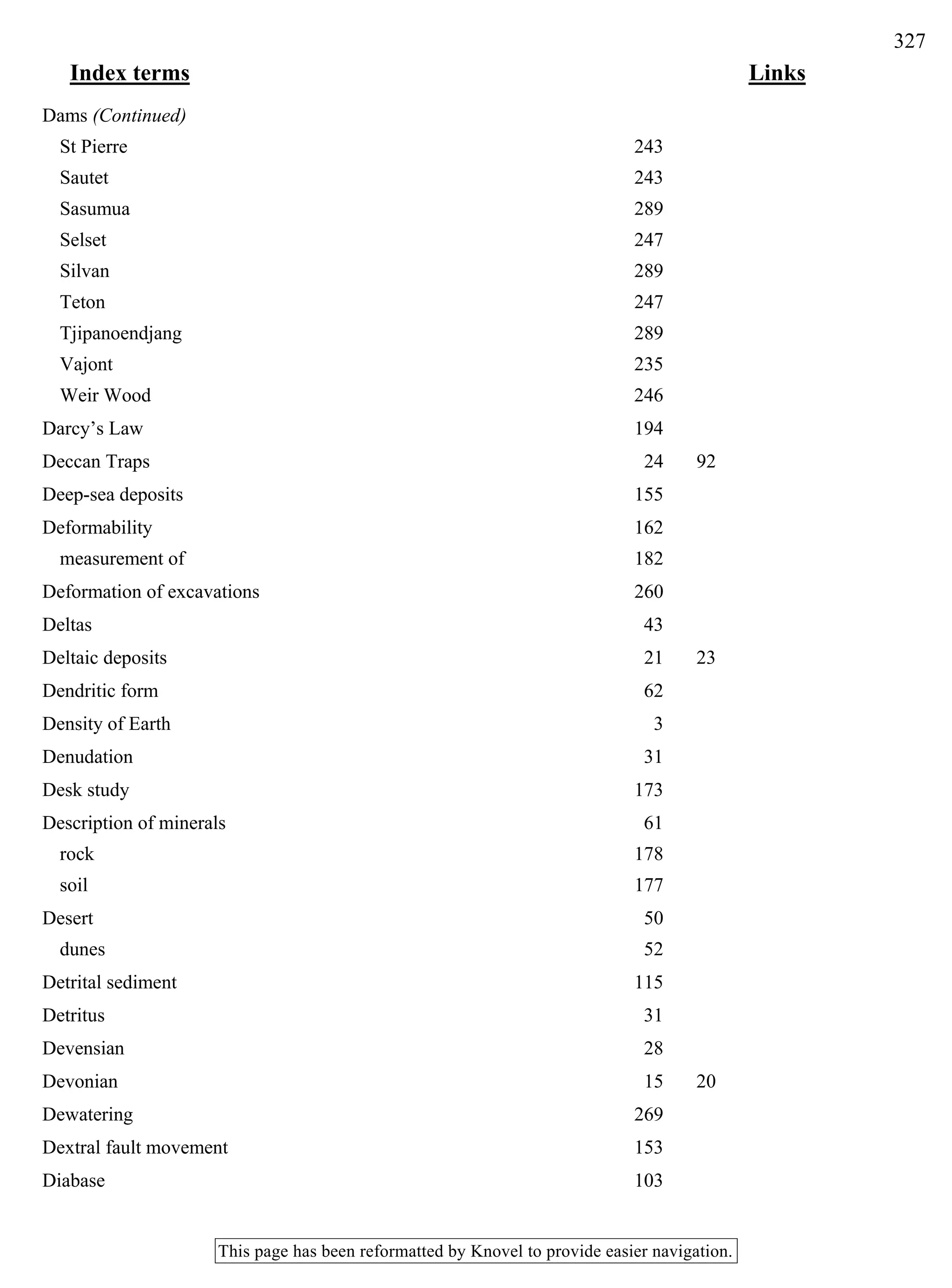

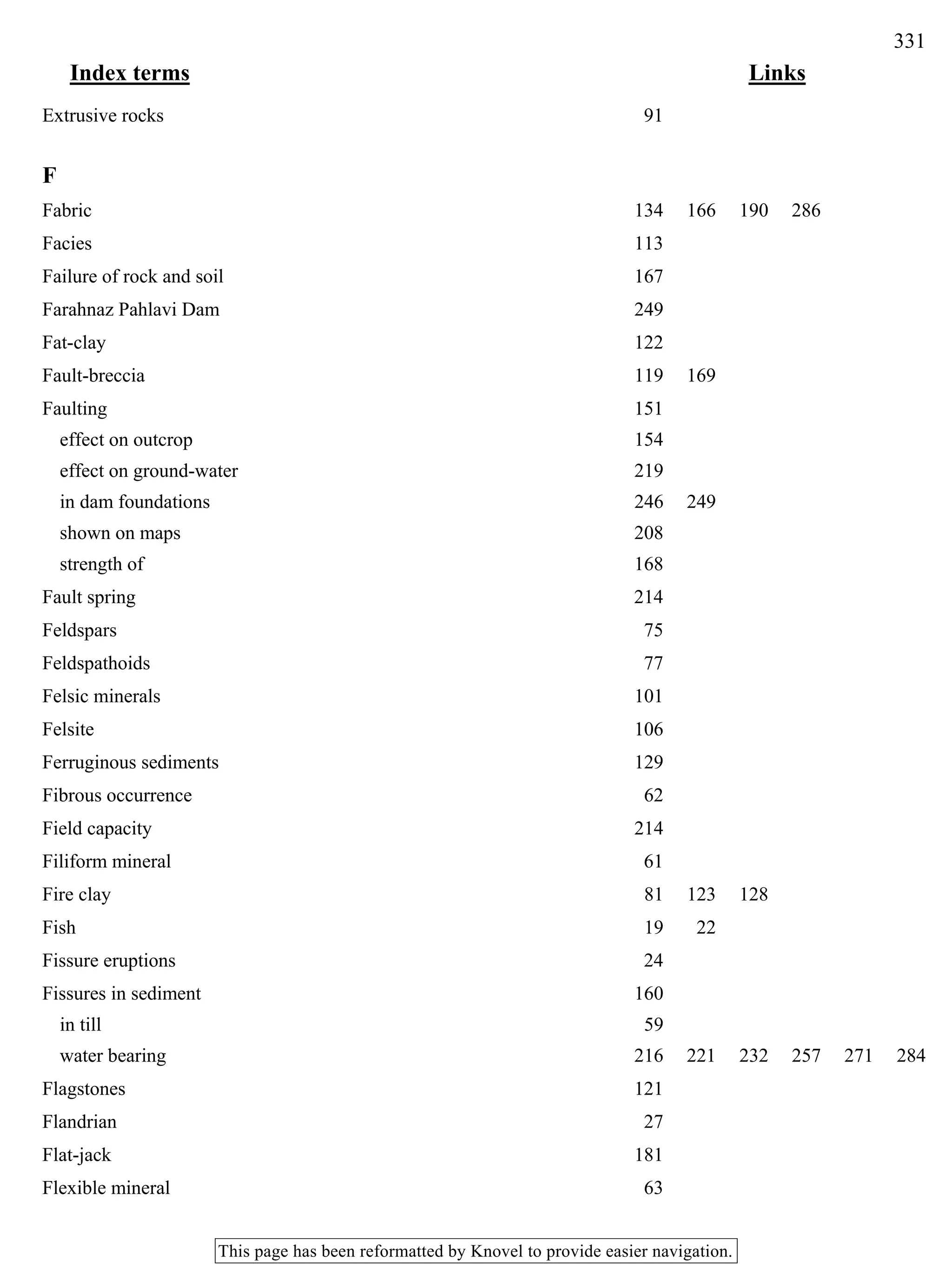

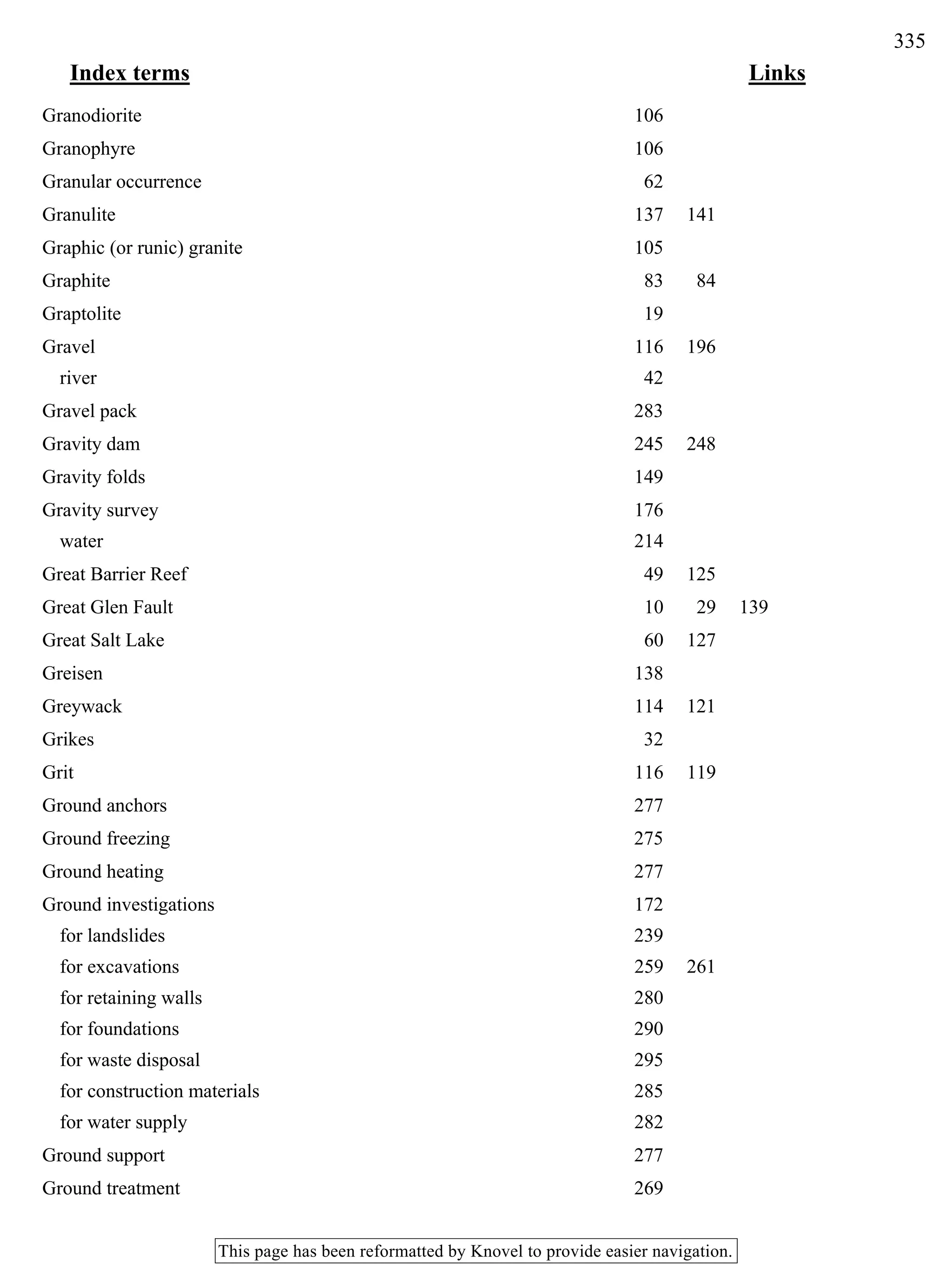

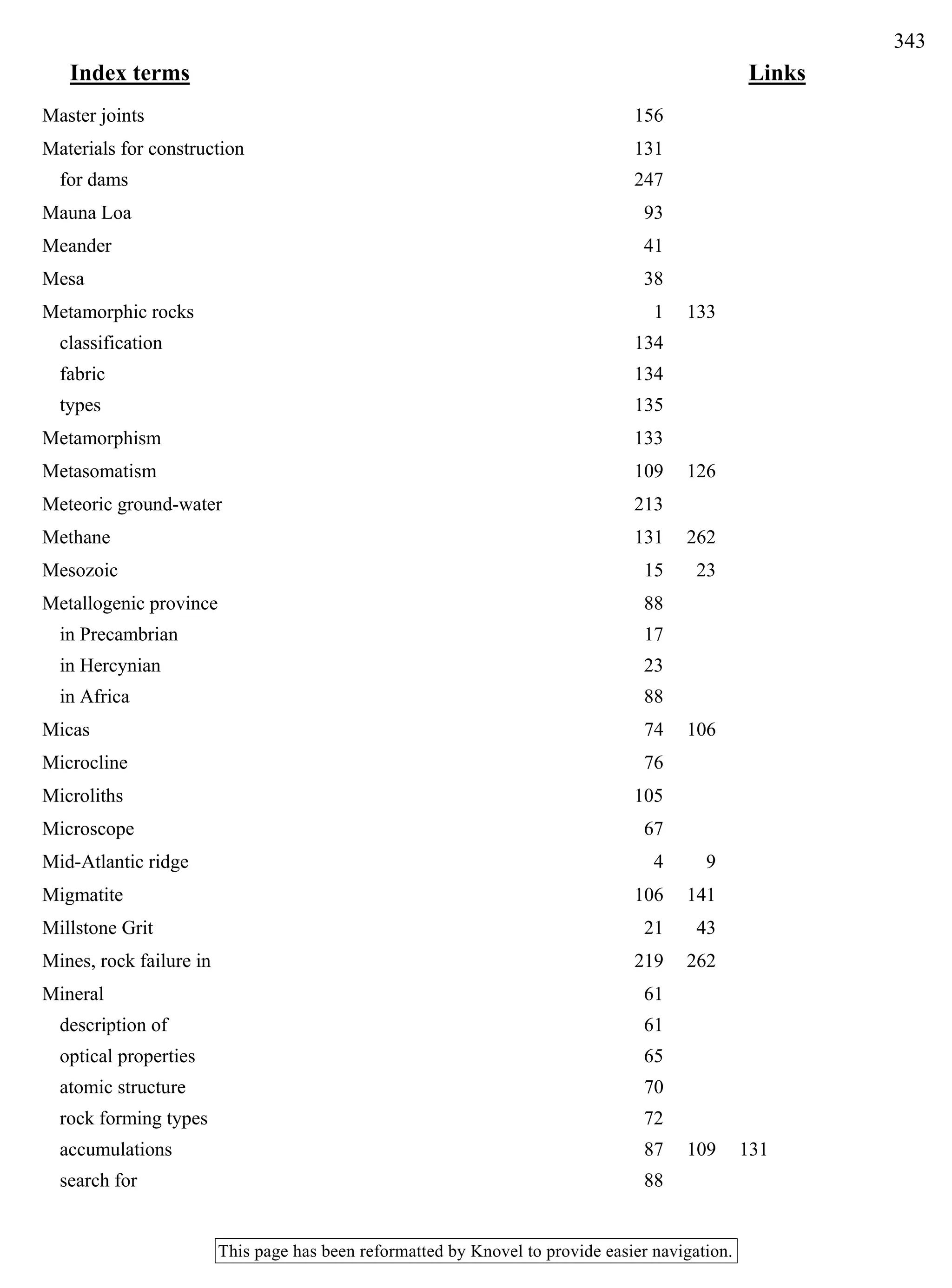

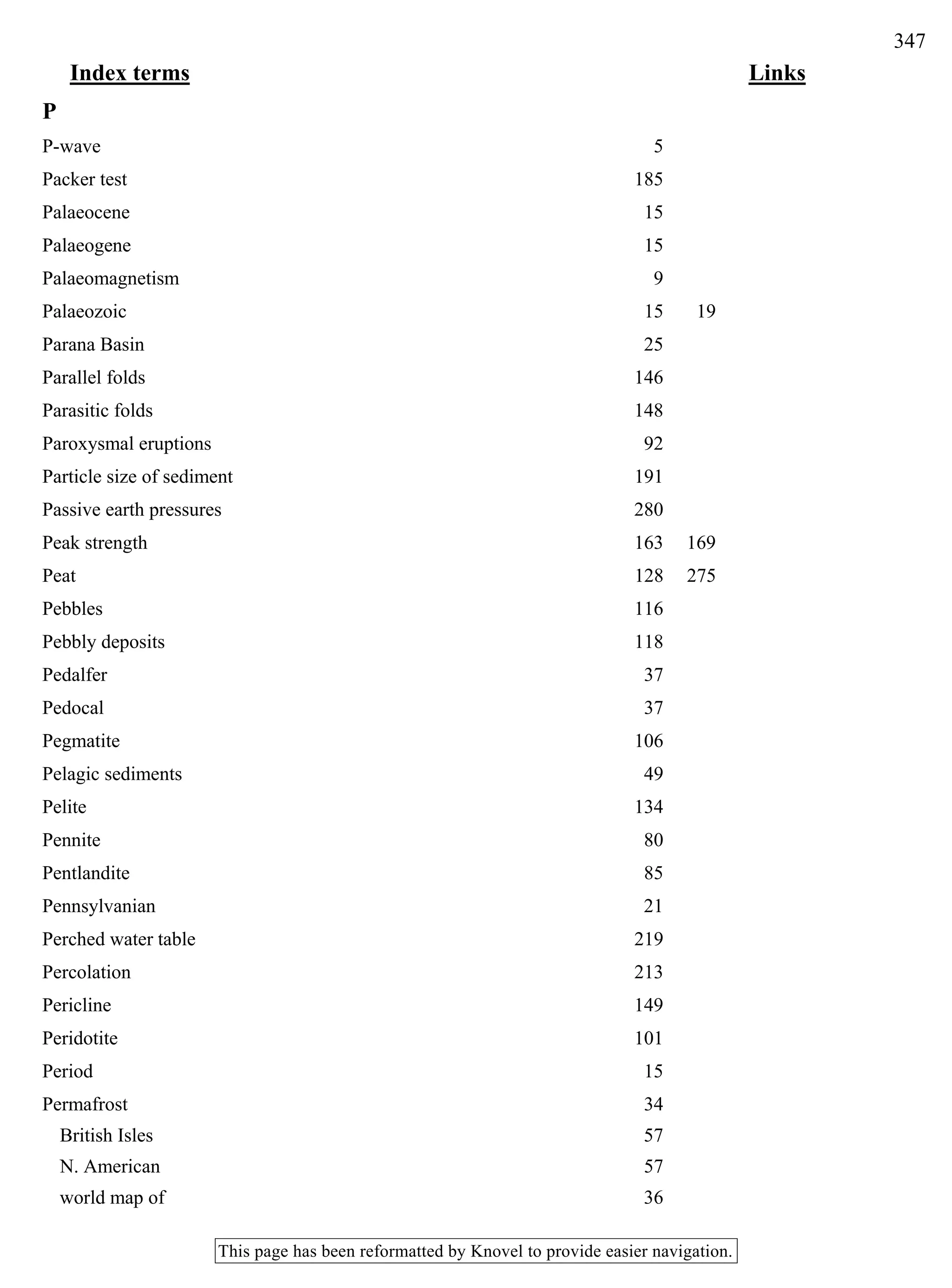

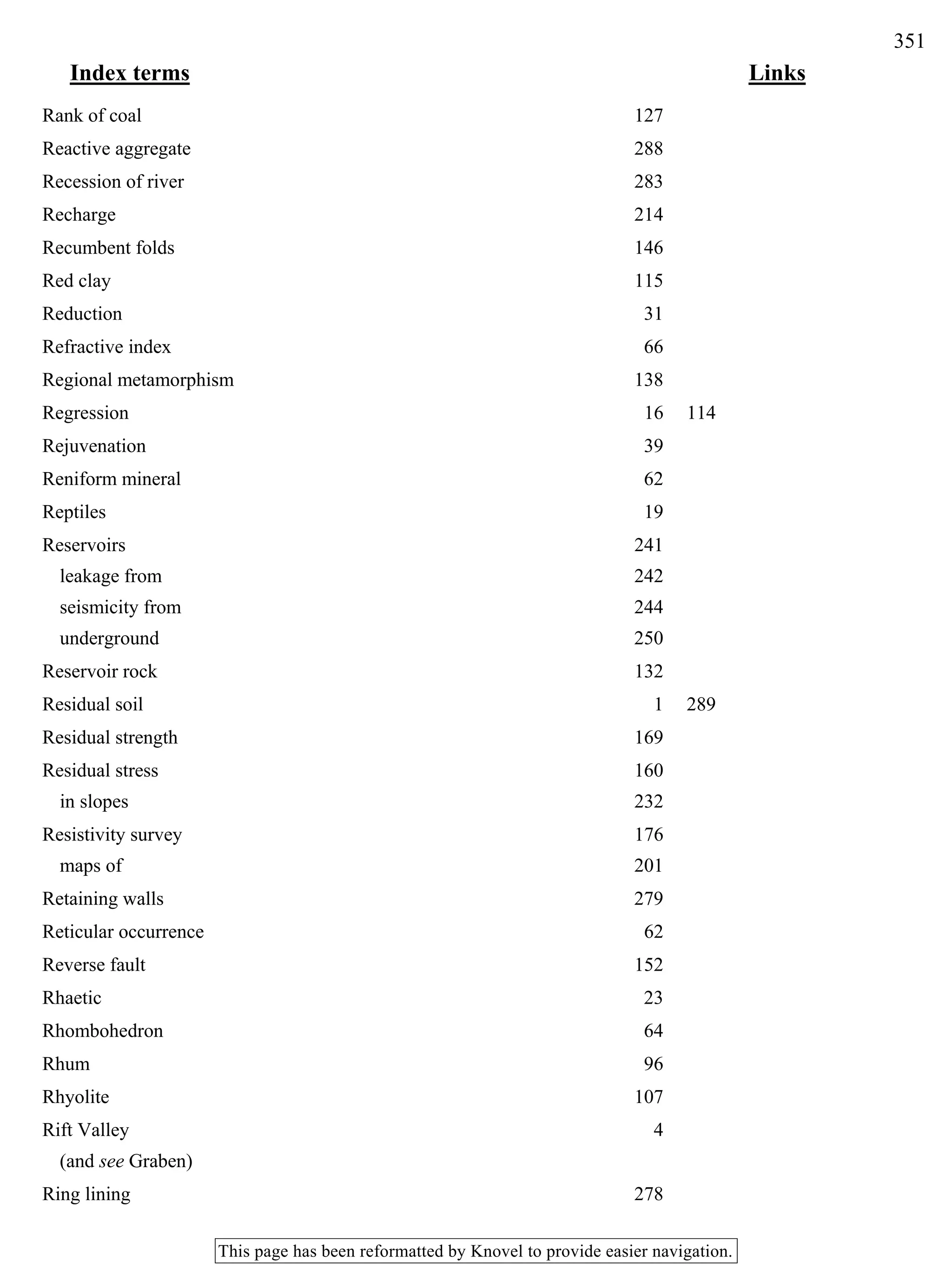

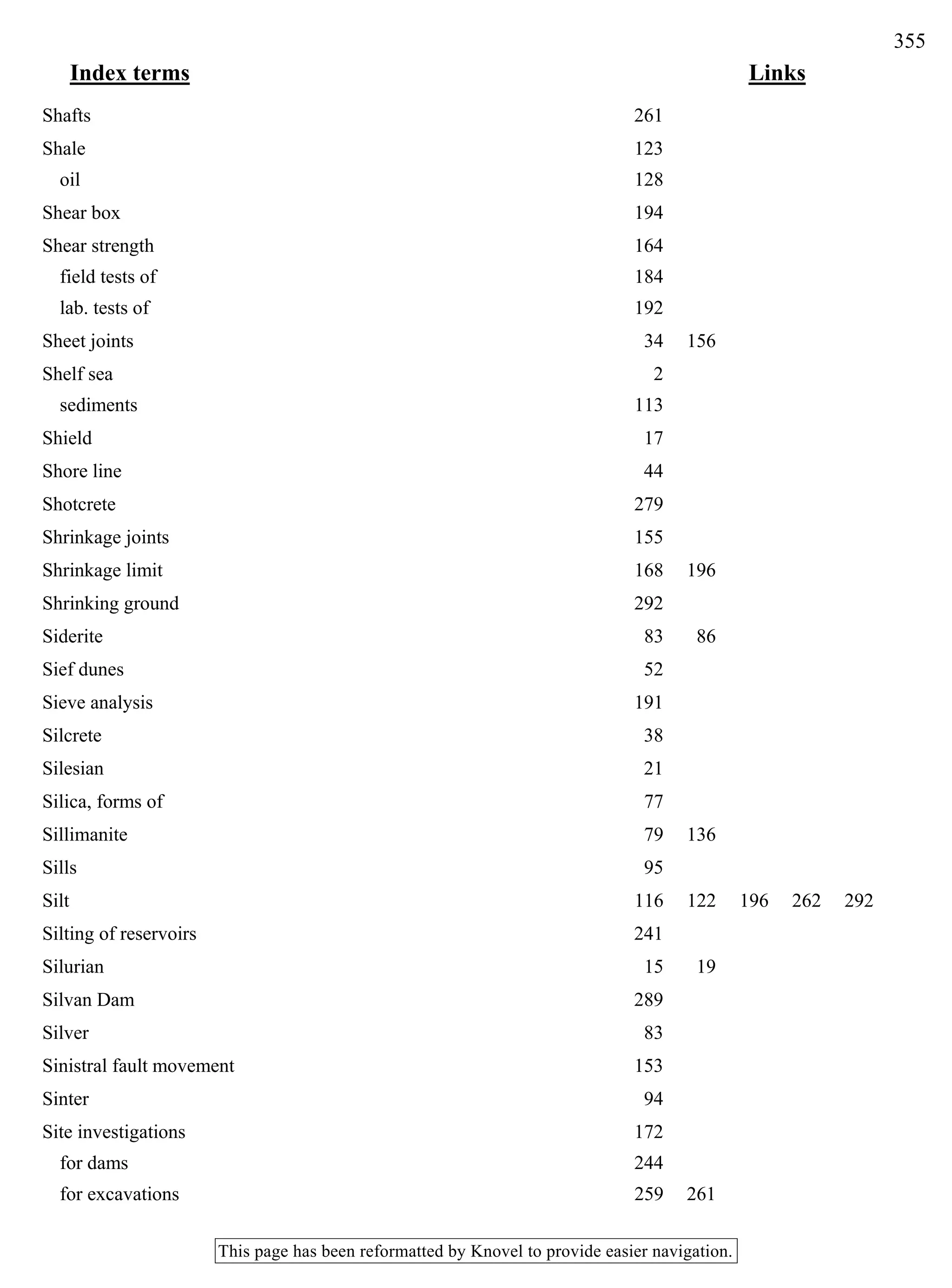

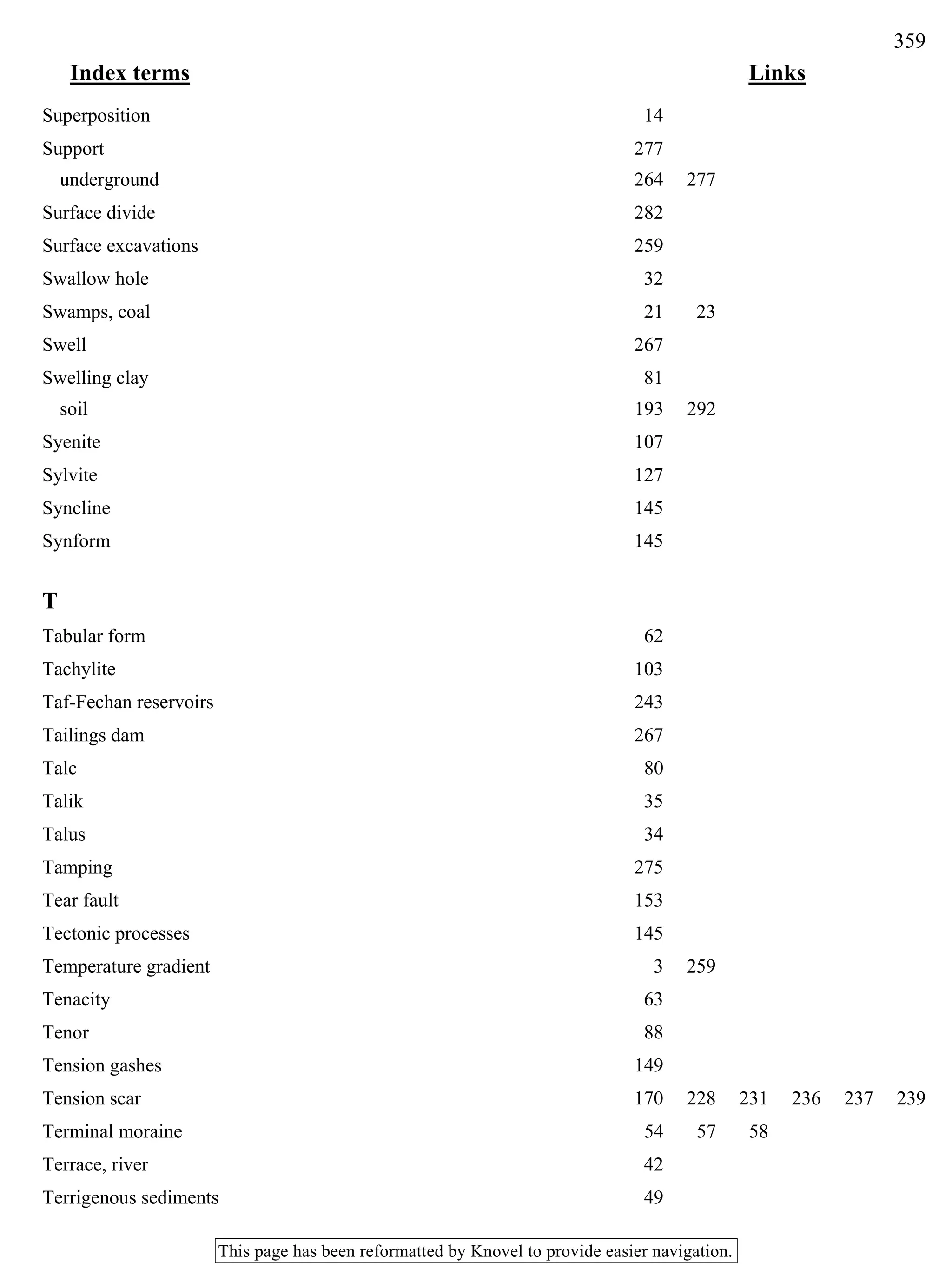

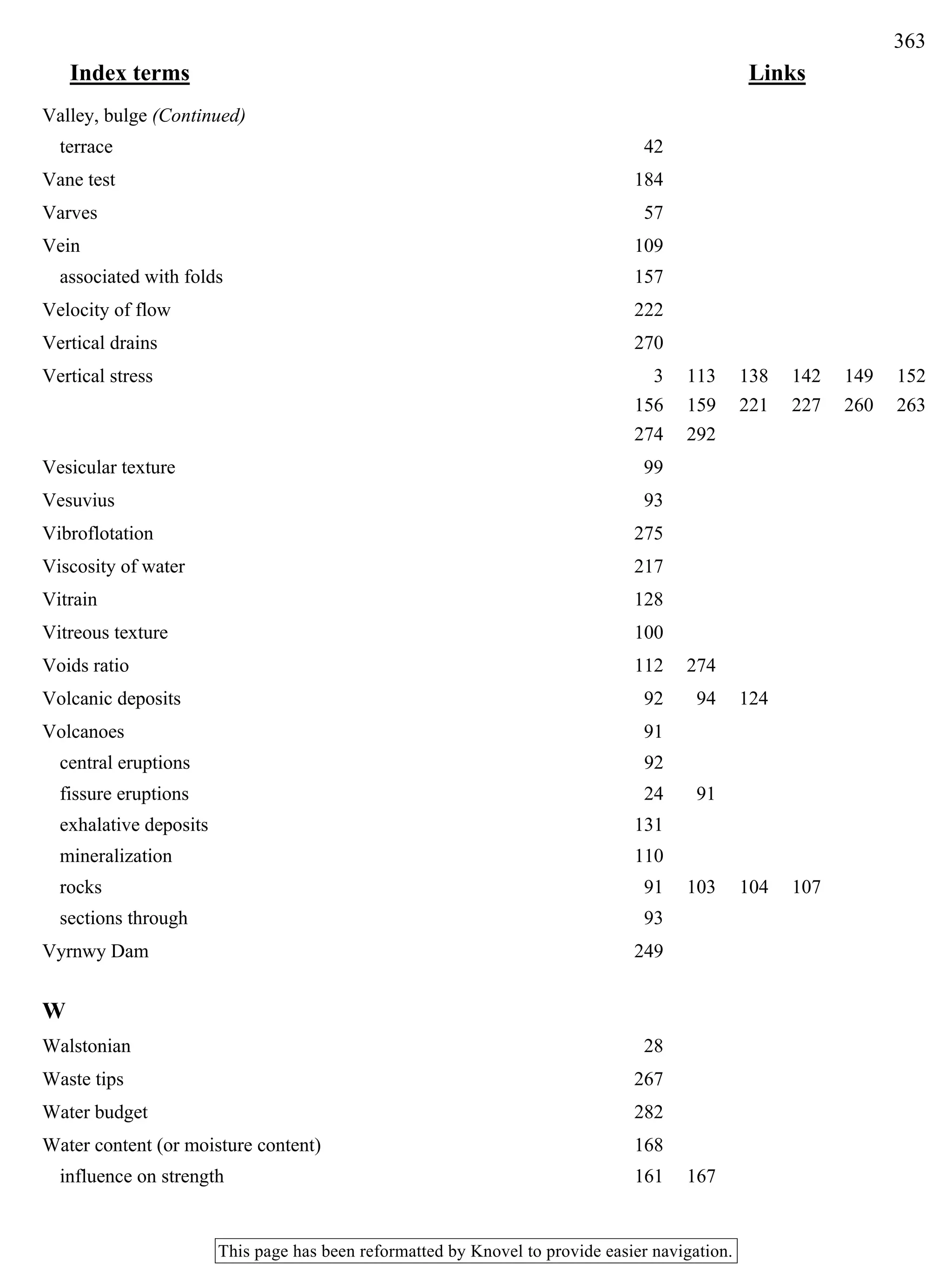

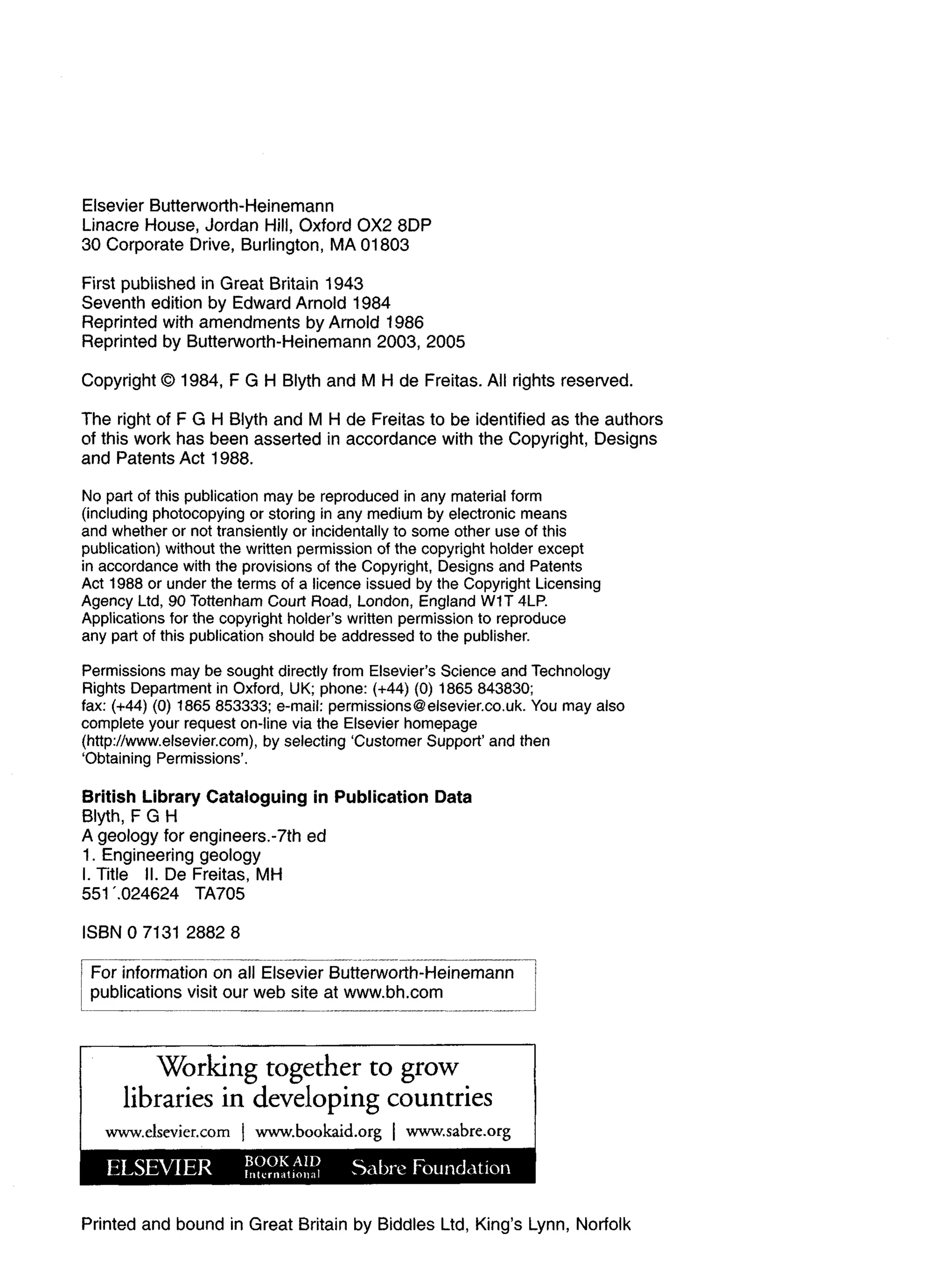

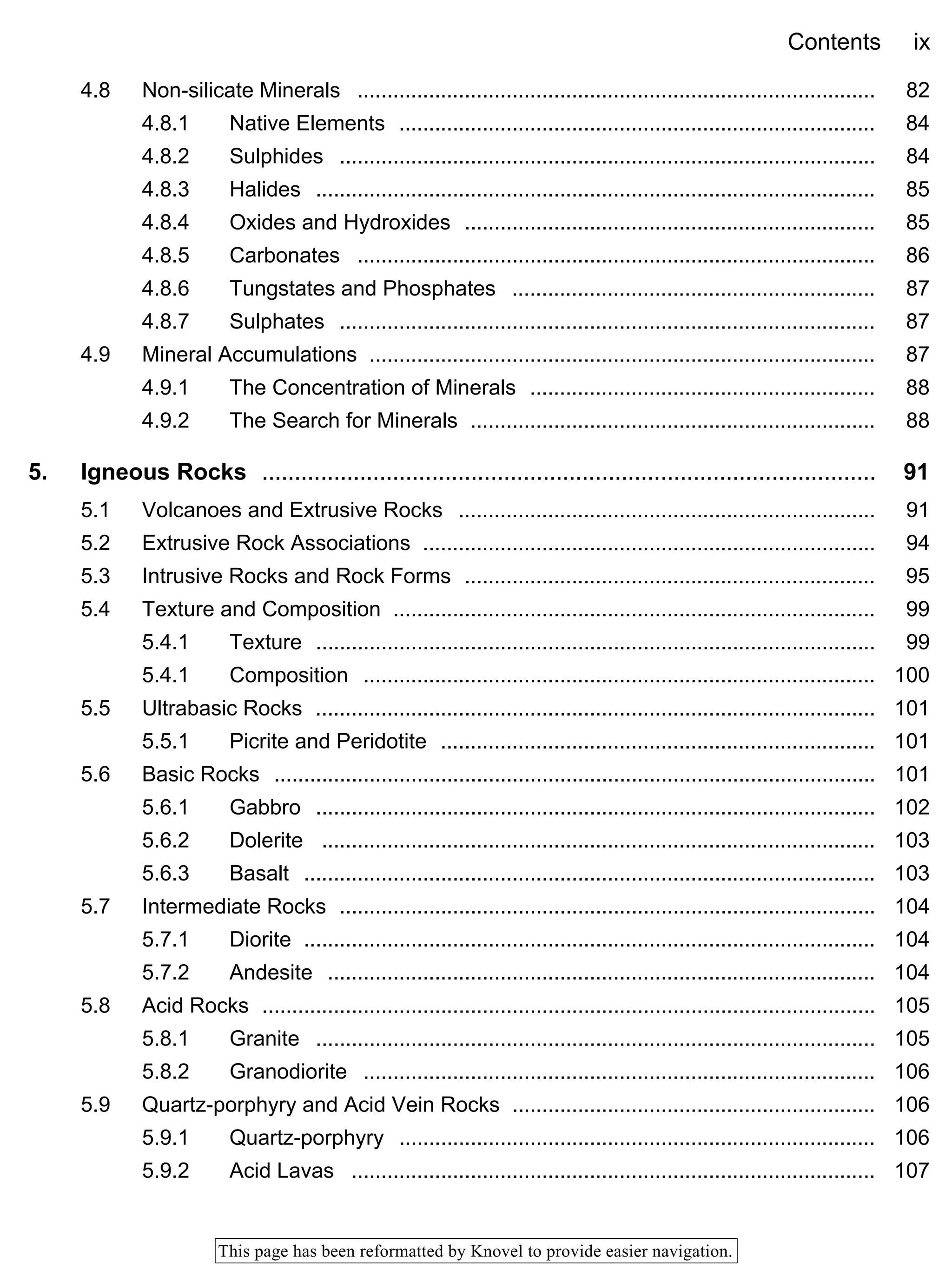

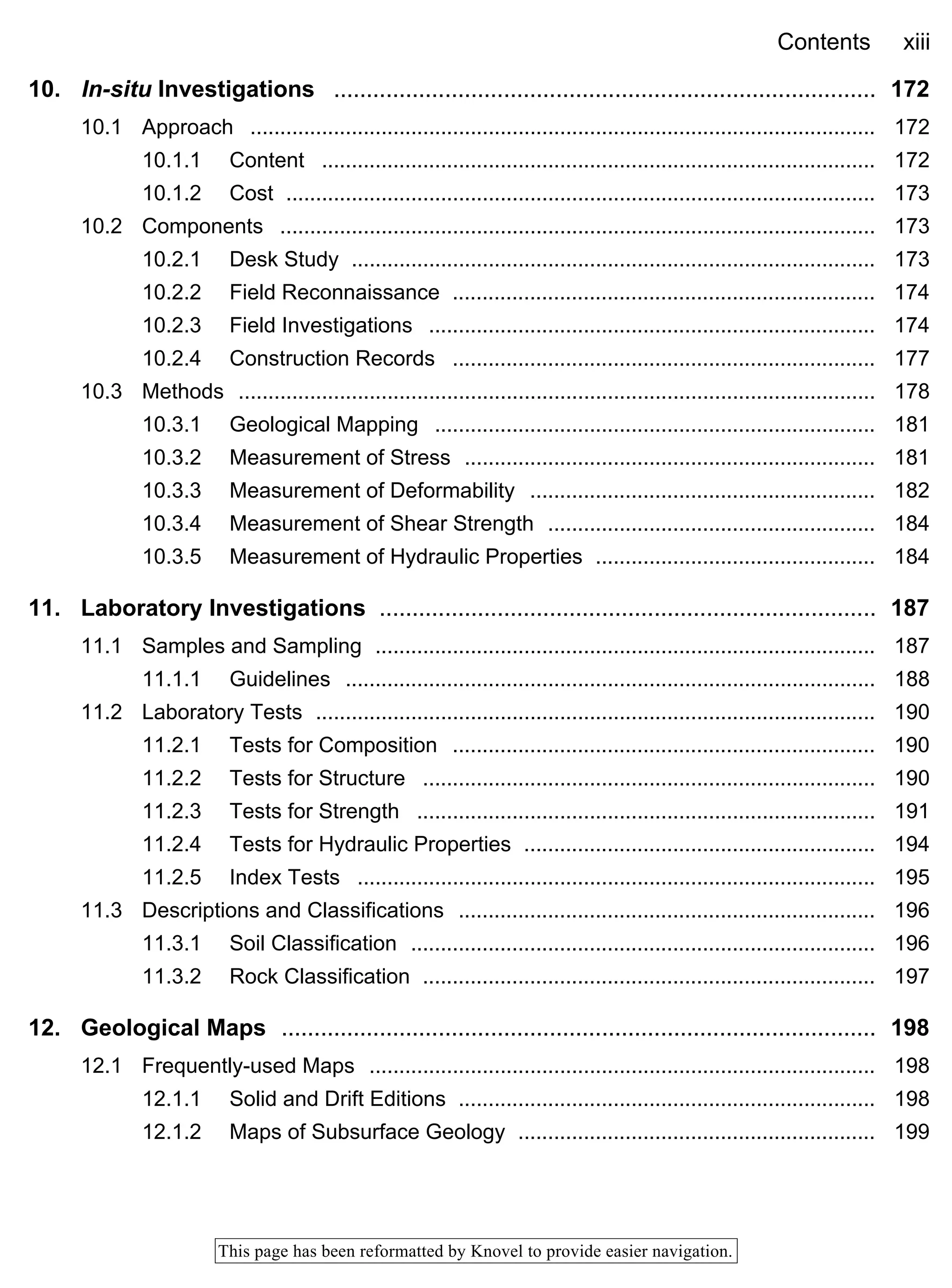

![may result from engineering work can be predicted by the

expression:

Au = B[Ao3 + A(Aa1-Aa3)]

Parameter A may be less than one, or negative, if the

deviator stress causing deformation and failure produces

a volumetric expansion of pore space sufficient to cause

pore pressure to decrease (cf. Figs 9.13, 9.15). When this

occurs effective stress on the surrounding particles and

hence the strength at their points of contact, will increase.

This increase in strength remains until more water can

migrate into the areas of reduced pore pressure and the

speed with which this occurs depends upon the permea-

bility of the material. For this reason the strength of

consolidated sediments and rocks of low permeability

may vary with time.

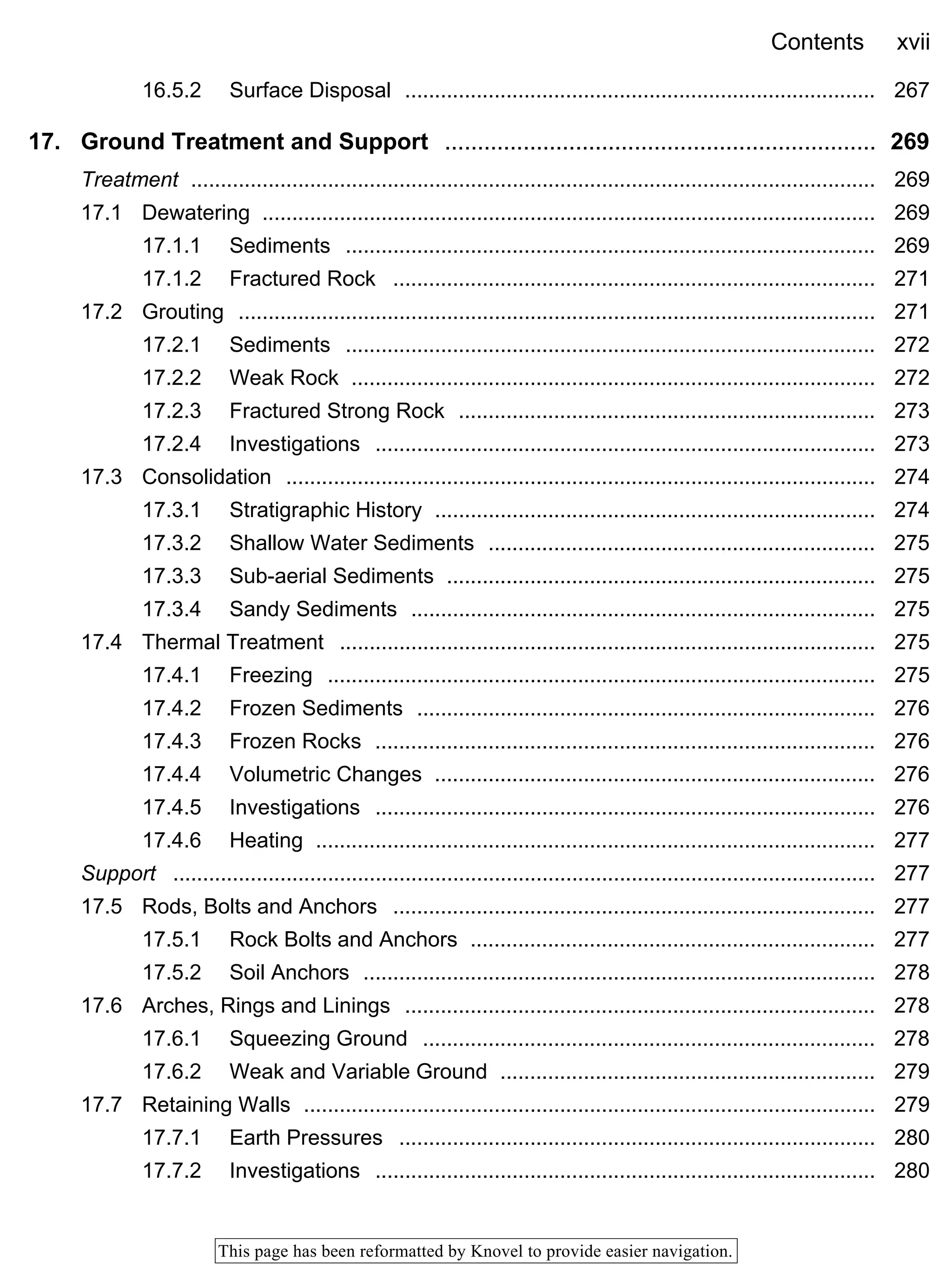

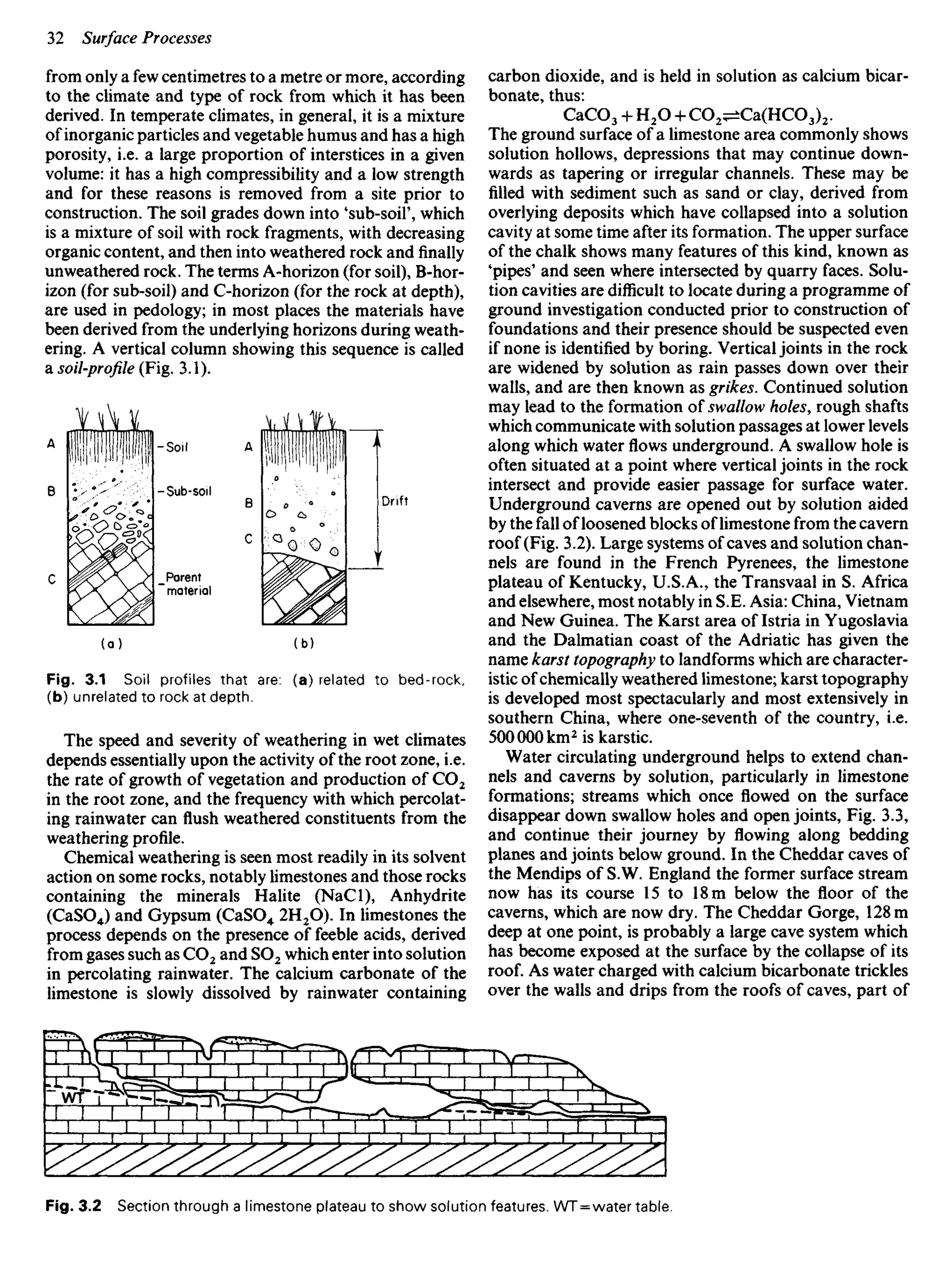

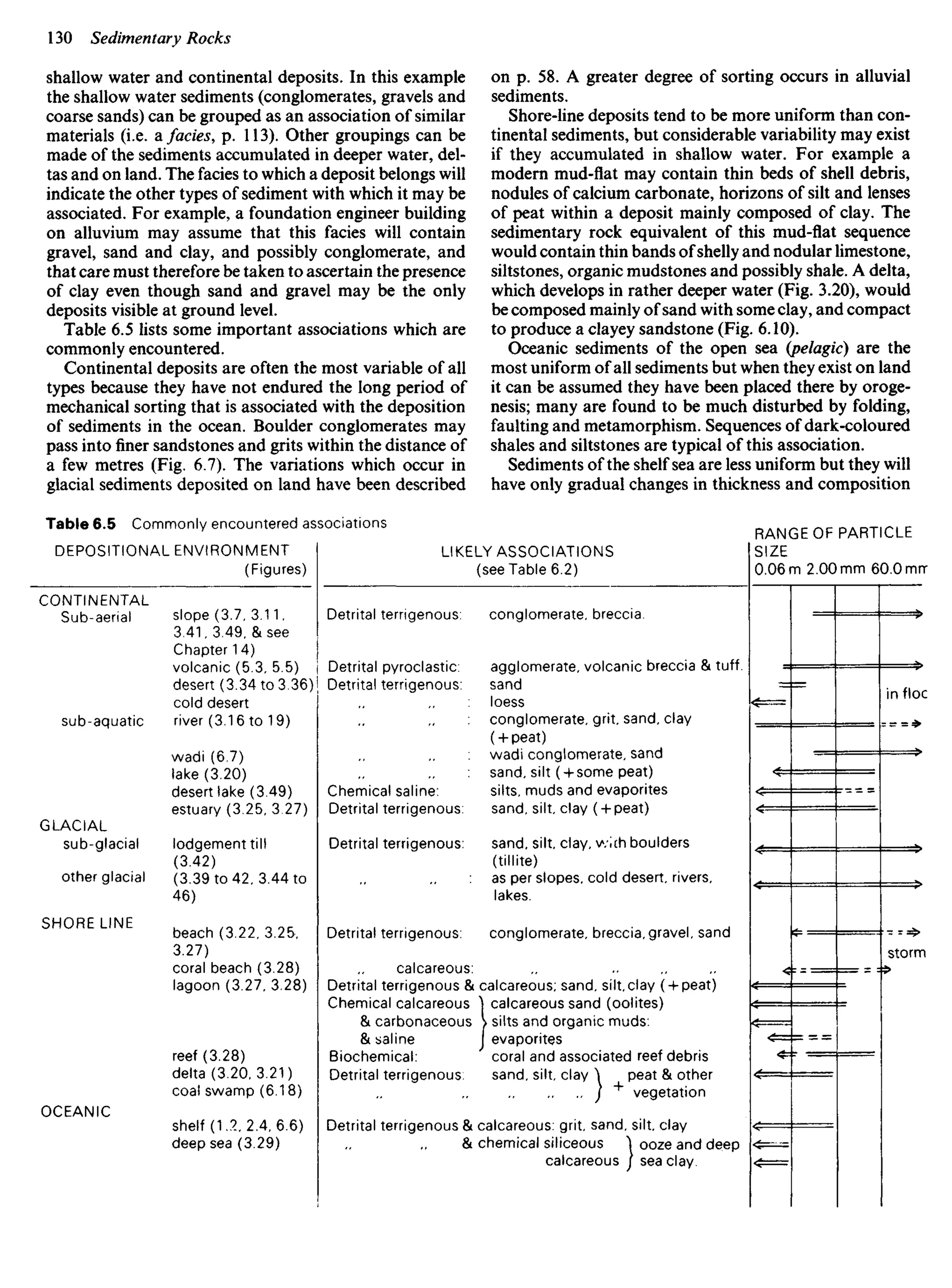

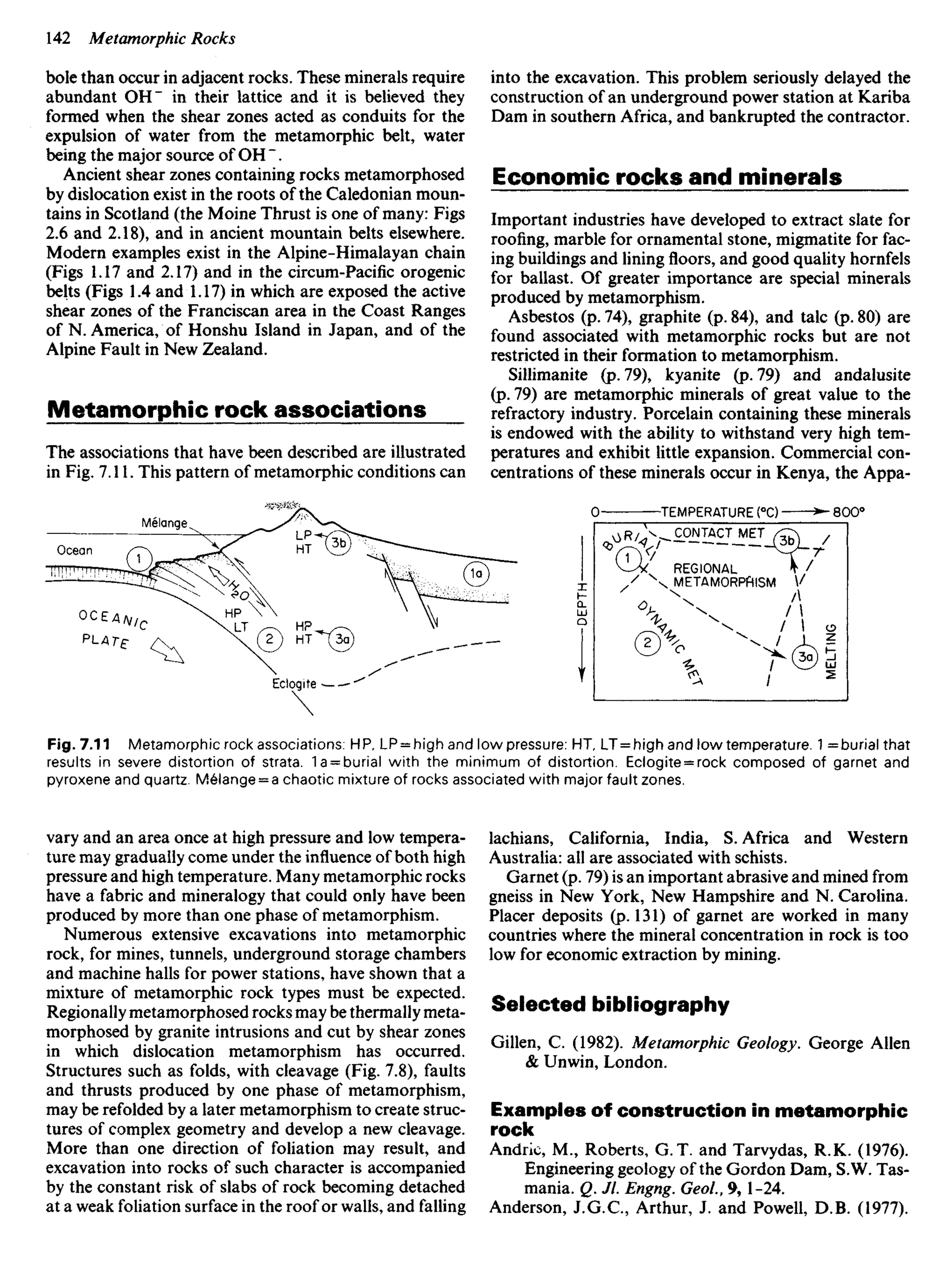

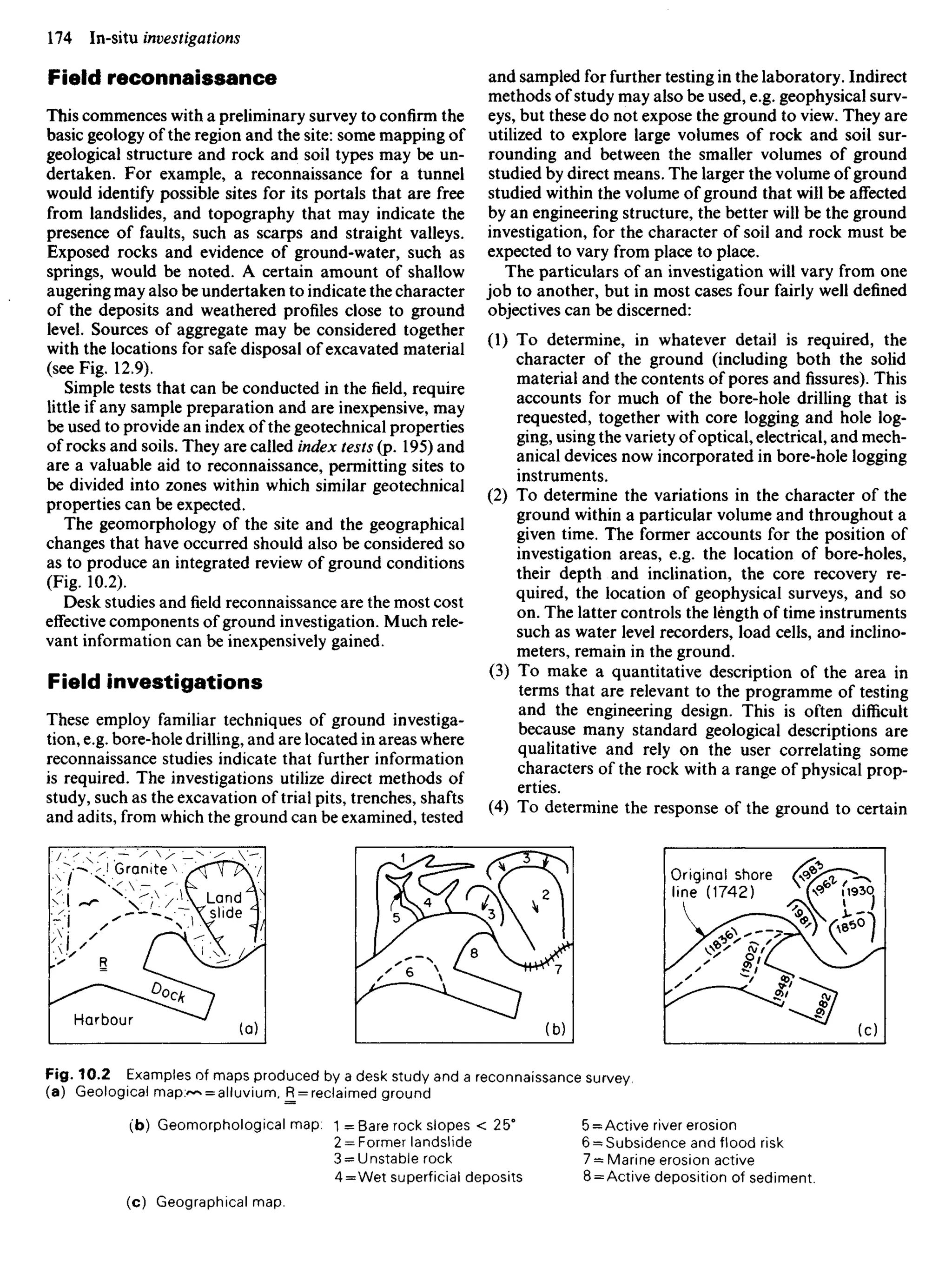

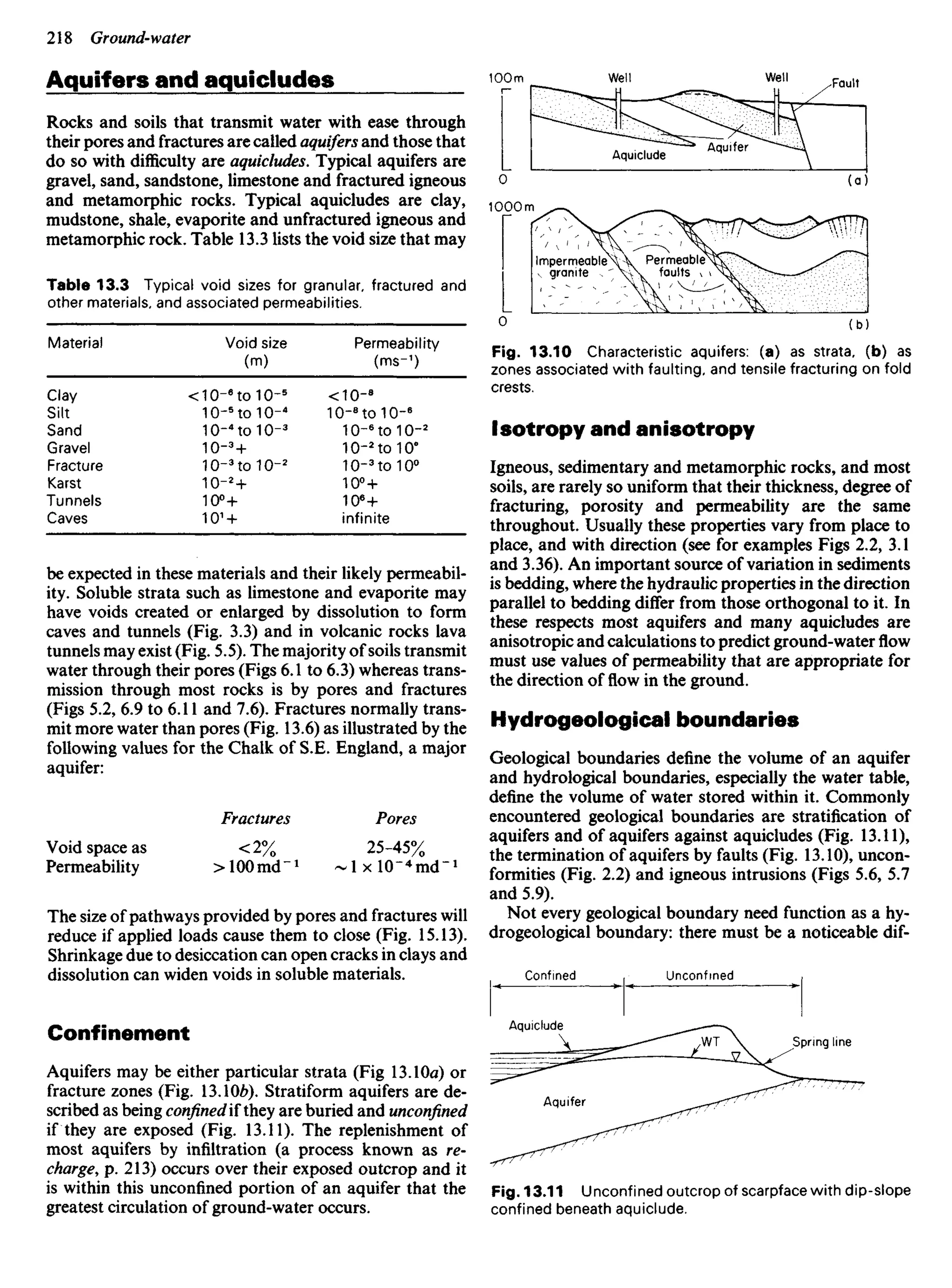

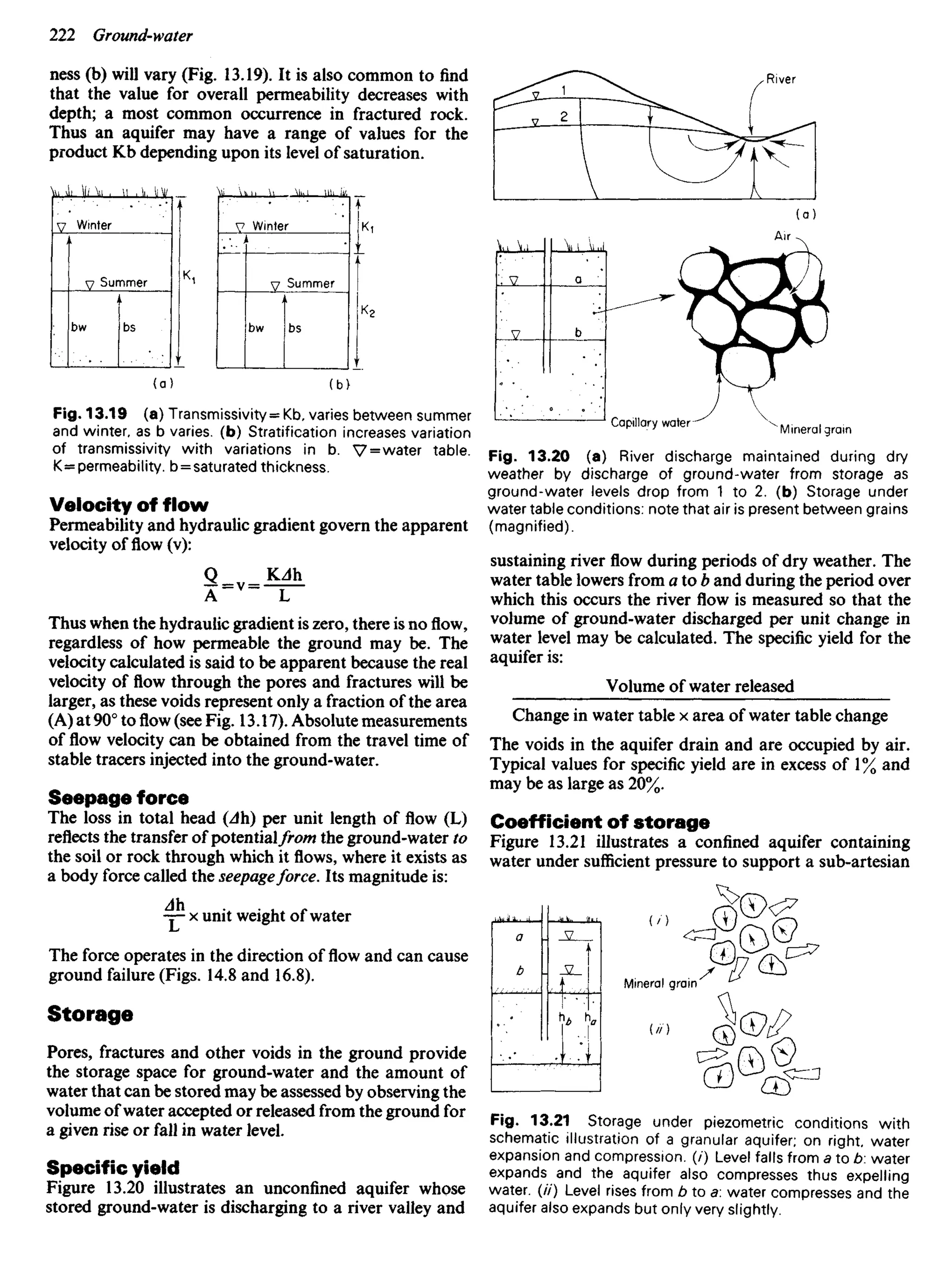

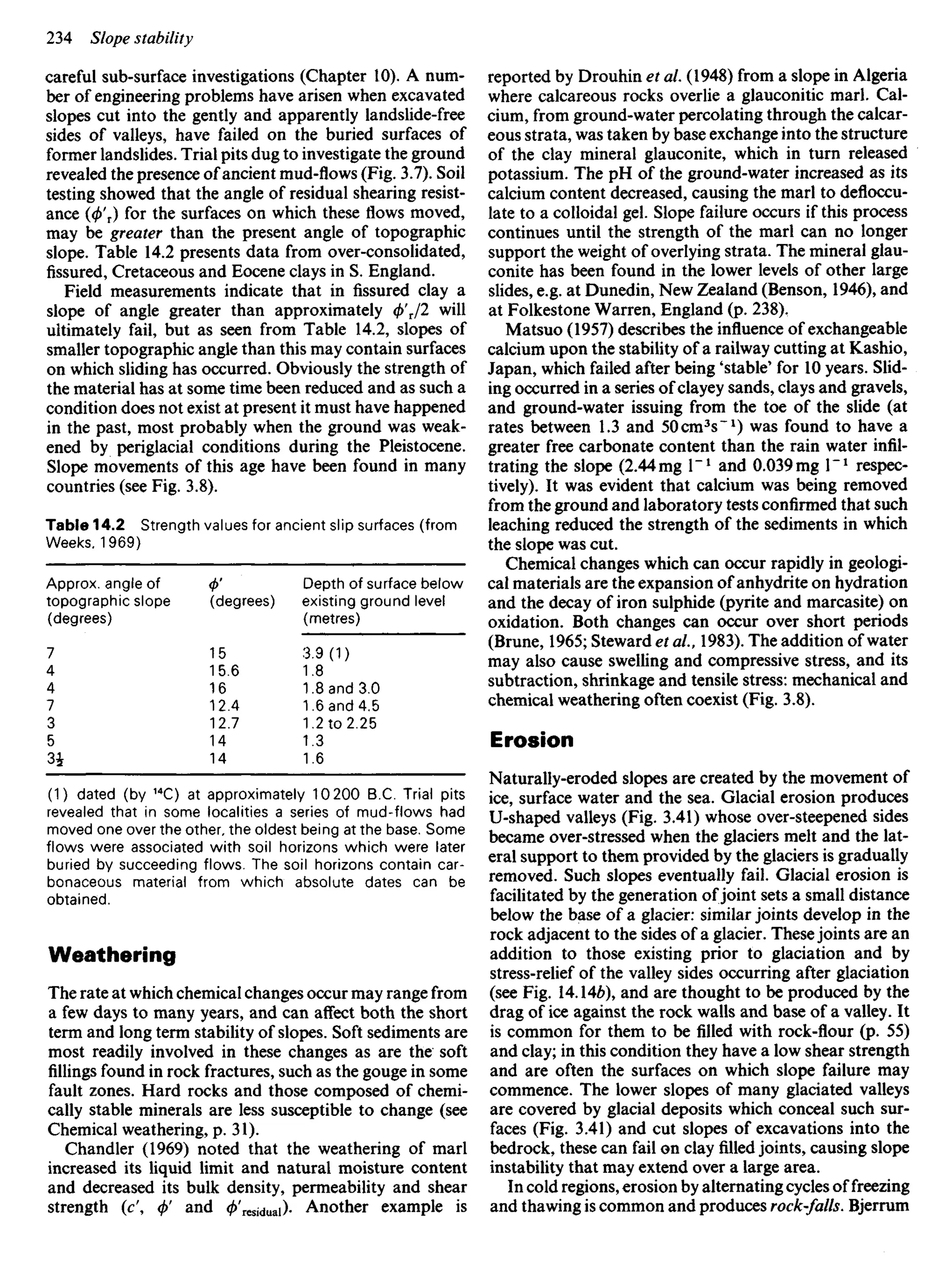

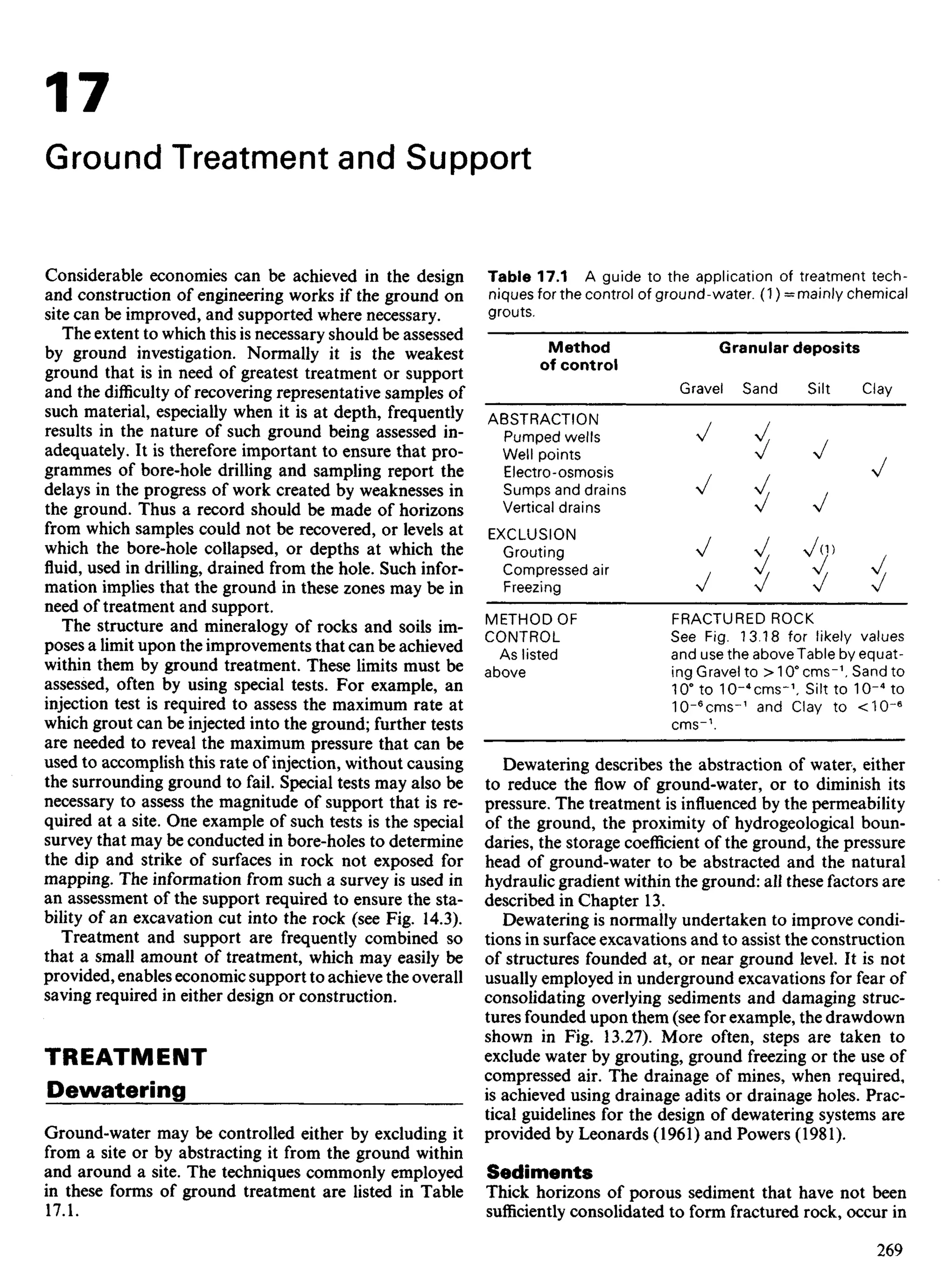

Table 9.3 Indicative values of pore-pressure parameter A

(Skempton, 1954 & 1961). Rocks may have negative values.

Soil Parameter A at failure

Loose sand 2.0 to 3.0

Soft clays Greater than 1.0

Normally consolidated clays 0.5 to 1.0

Over-consolidated clays 0.25 to 0.5

Heavily over-consolidated clays 0.5 and less

content at which the character of the soil is essentially

that a solid (as in a brick made from dry mud), or a plastic

(as in clay ready for moulding by a potter), or a liquid (as

in a slurry) is provided by index tests (p. 195) which define

the consistency limits: the limits are illustrated in

Fig. 9.22a. In these tests the samples are totally re-

moulded to prevent soil fabric from contributing to their

behaviour. The limits therefore reflect the mineralogy of

the soil (Fig. 9.22Z>).

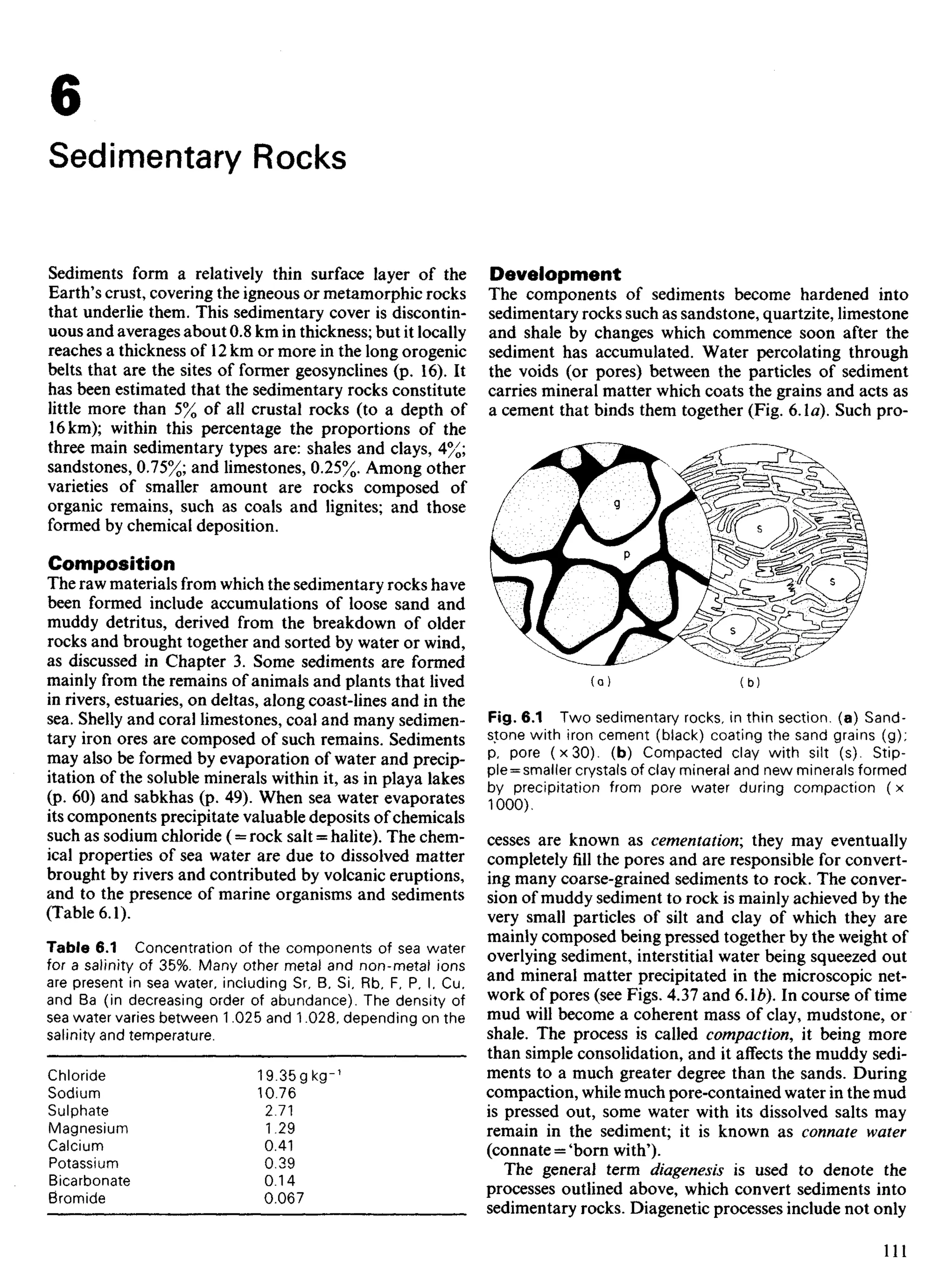

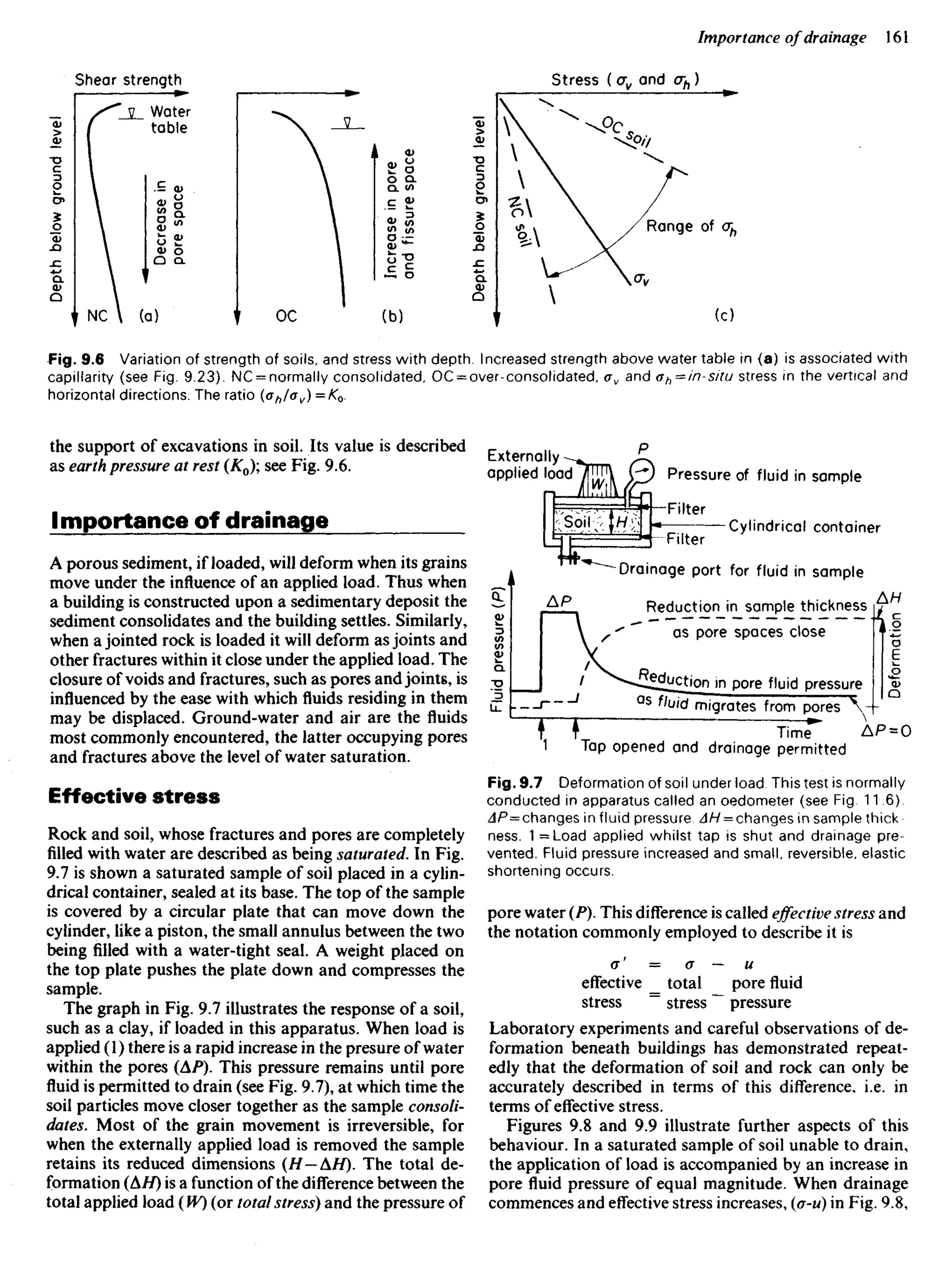

Weak soils, such as loose sand, that are partially satu-

rated may gain strength from the capillary tension of the

water meniscus around their areas of grain contact

(Fig. 9.23). This increases the effective stress upon the

grains and thus the frictional resistance at their points of

contact.

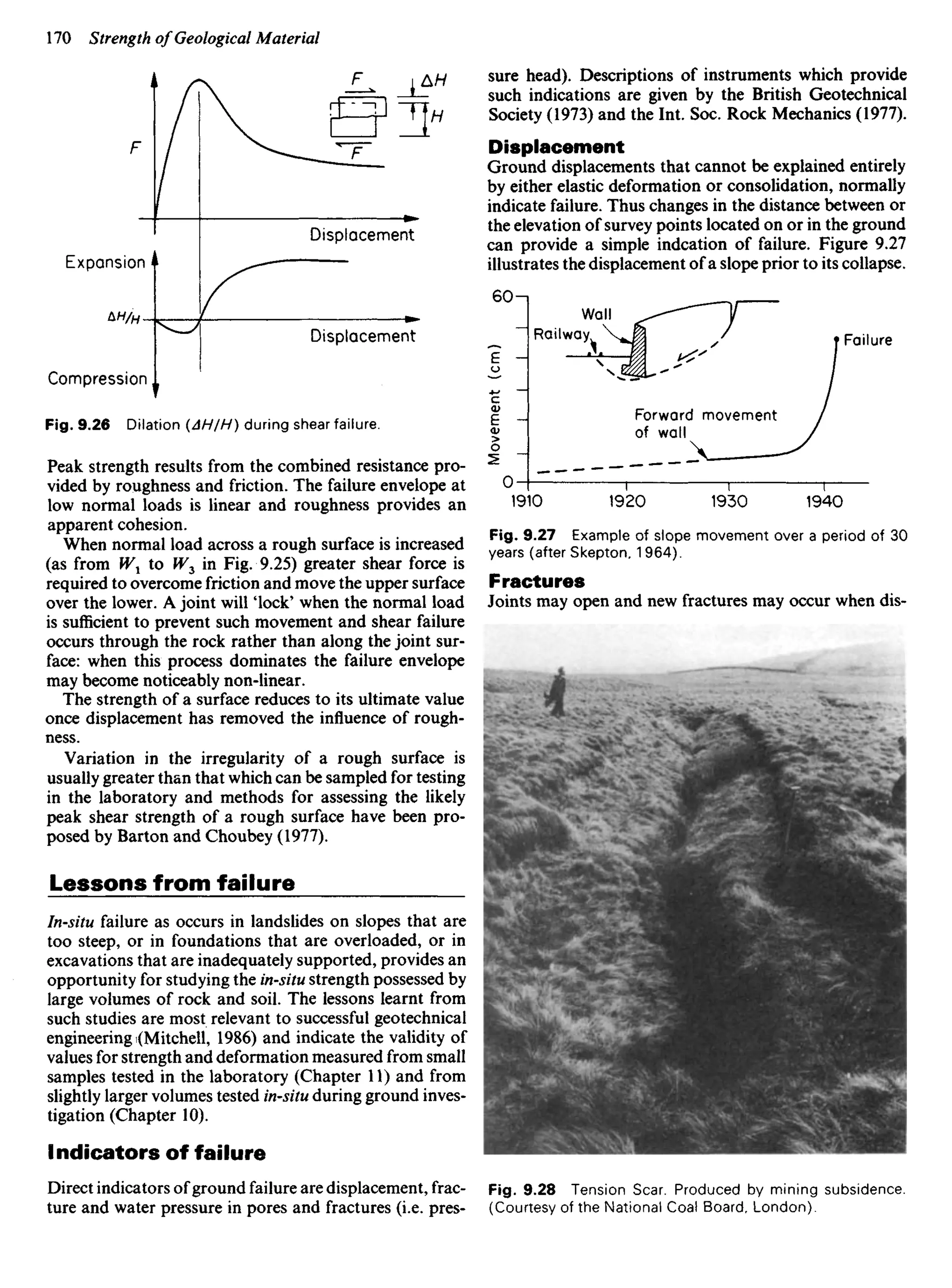

Mineral grain

Pore space

filled with air

at atmospheric

pressure Capillary

meniscus

Mineral grain

Consistency limits

The volume and strength of most soils varies with their

water content and the limit of this variation, i.e. the water Fig. 9.23 Capillary tension in pore spaces between mineral

grains. Large arrows indicate the attraction between grains

created by the meniscus.

Elastic moduli

Values of Young's Modulus and Poisson's ratio may be

obtained for rock and soil with comparative ease, but the

significance of the values obtained must be considered

with care as they may vary with time from those applic-

able to undrained conditions to those for drained condi-

tions. This is especially important for soils, where these

moduli should be determined experimentally using con-

ditions that simulate the range of stresses and type of

deformation that are expected to operate in the ground

during the engineering works.

Behaviour of surfaces

Over-consolidated sediments and all rocks that have ex-

perienced unloading and uplift (p. 160) contain micro-

fractures and other failure surfaces such as joints and

fissures: many bedding planes will have separated, some

containing a visible parting. Such surfaces have a strength

that is less than that of the rock or soil in which they

occur and they are a major source of weakness: they have

formed by failure either in tension or in shear.

Tensile fractures such as joints, tend to be discontin-

Volume

No further decrease

in volume with

drying LIQUID

PLASTIC

Plasticity

index

Water

content

Water

content

(%)

Sandy

silts

Silt

Silty

clay

Clay

SOLID

Plasticity index

Fig. 9.22 (a) Consistency limits: SL — shrinkage limit.

P/. = plastic limit. Z./.= liquid limit, I/=total soil vol

ume = volume of pores (VP) + volume of solid grains (V$)

Water content= (Mass of water) 4- (mass of solid) and can be

more than 100%. (b) Influence of mineralogy upon consis-

tency limits.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ageologyforengineersseventhedition-240123054612-a0c16209/75/A_Geology_for_Engineers_Seventh_Edition-pdf-152-2048.jpg)

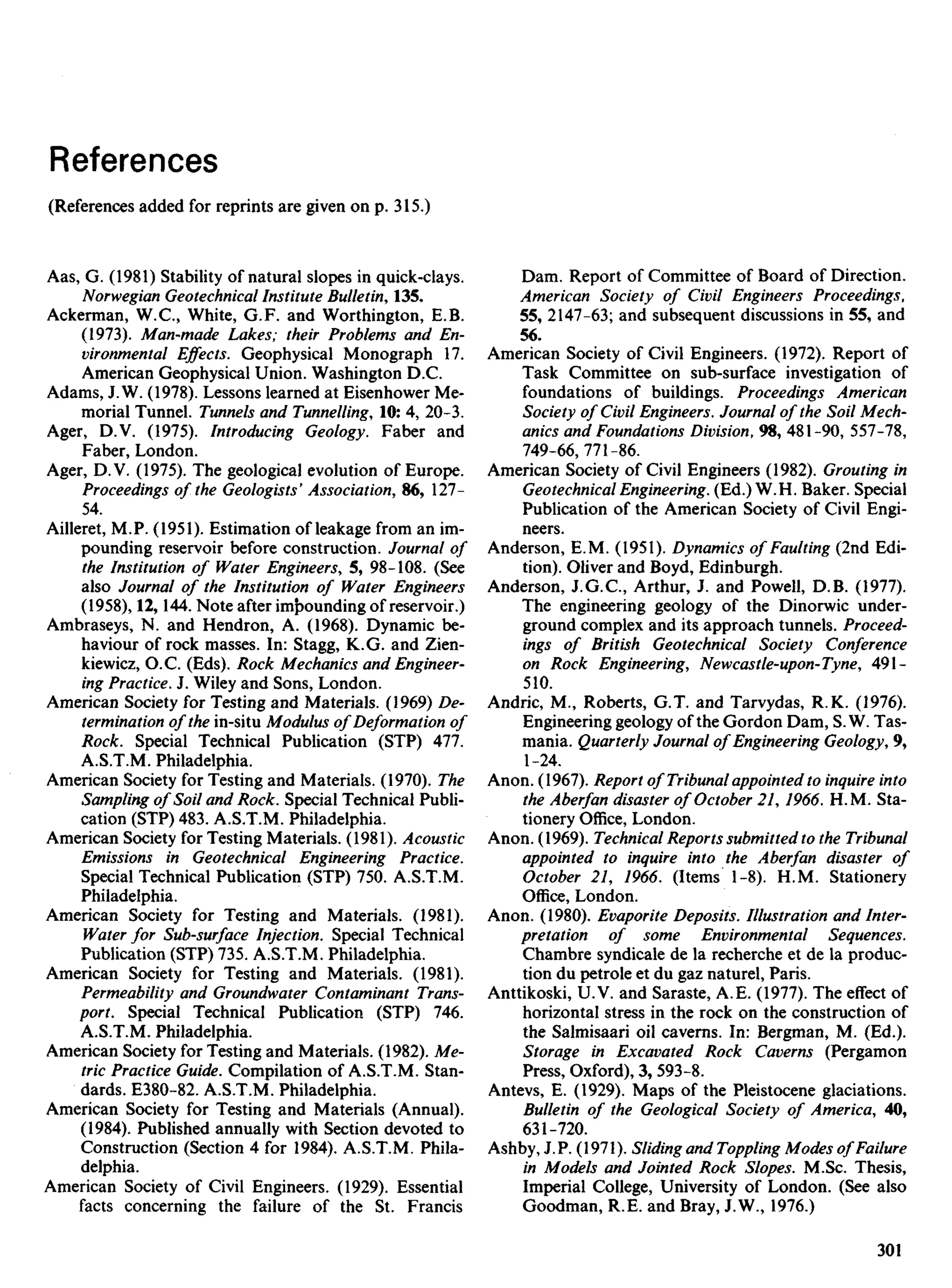

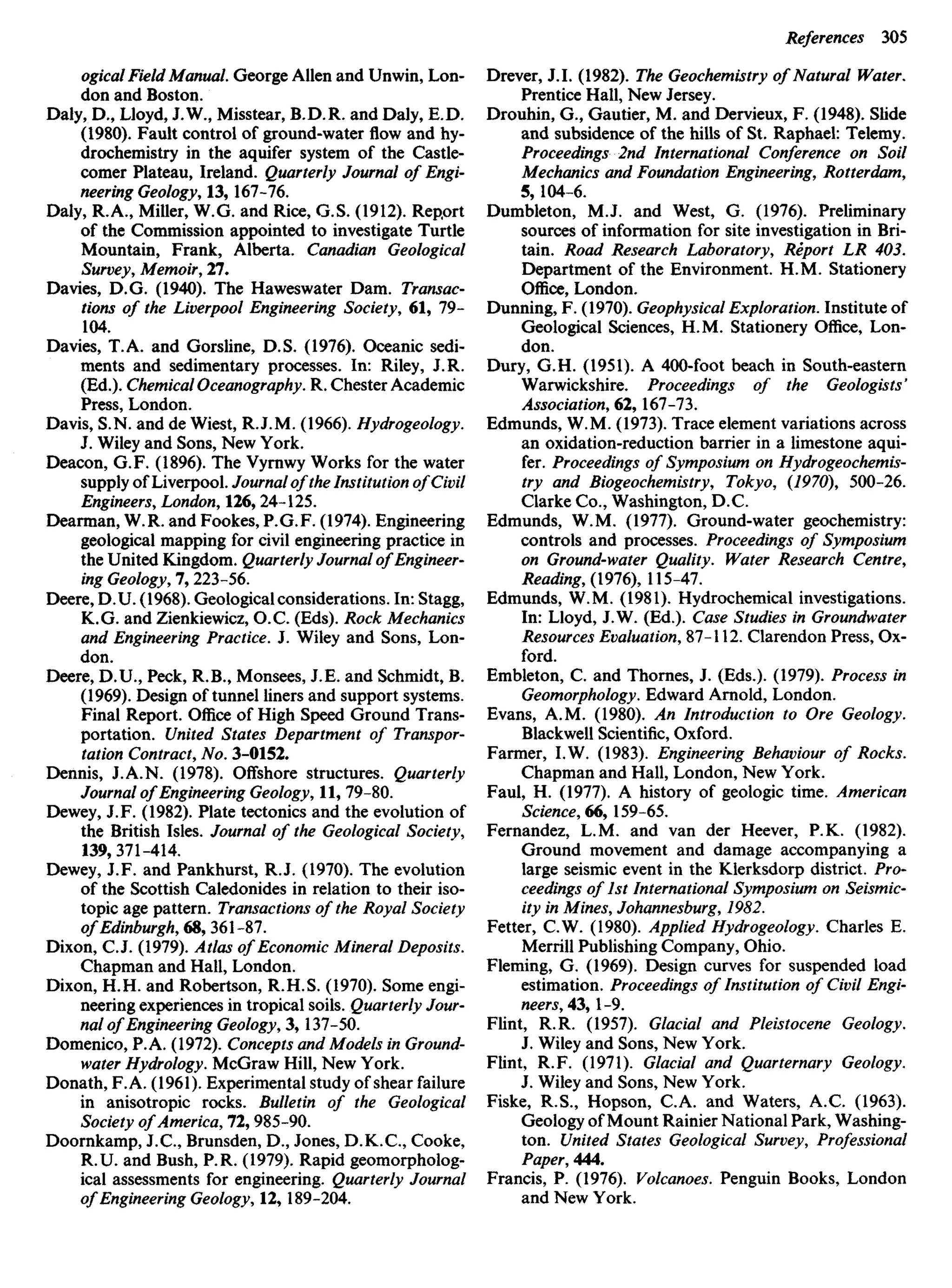

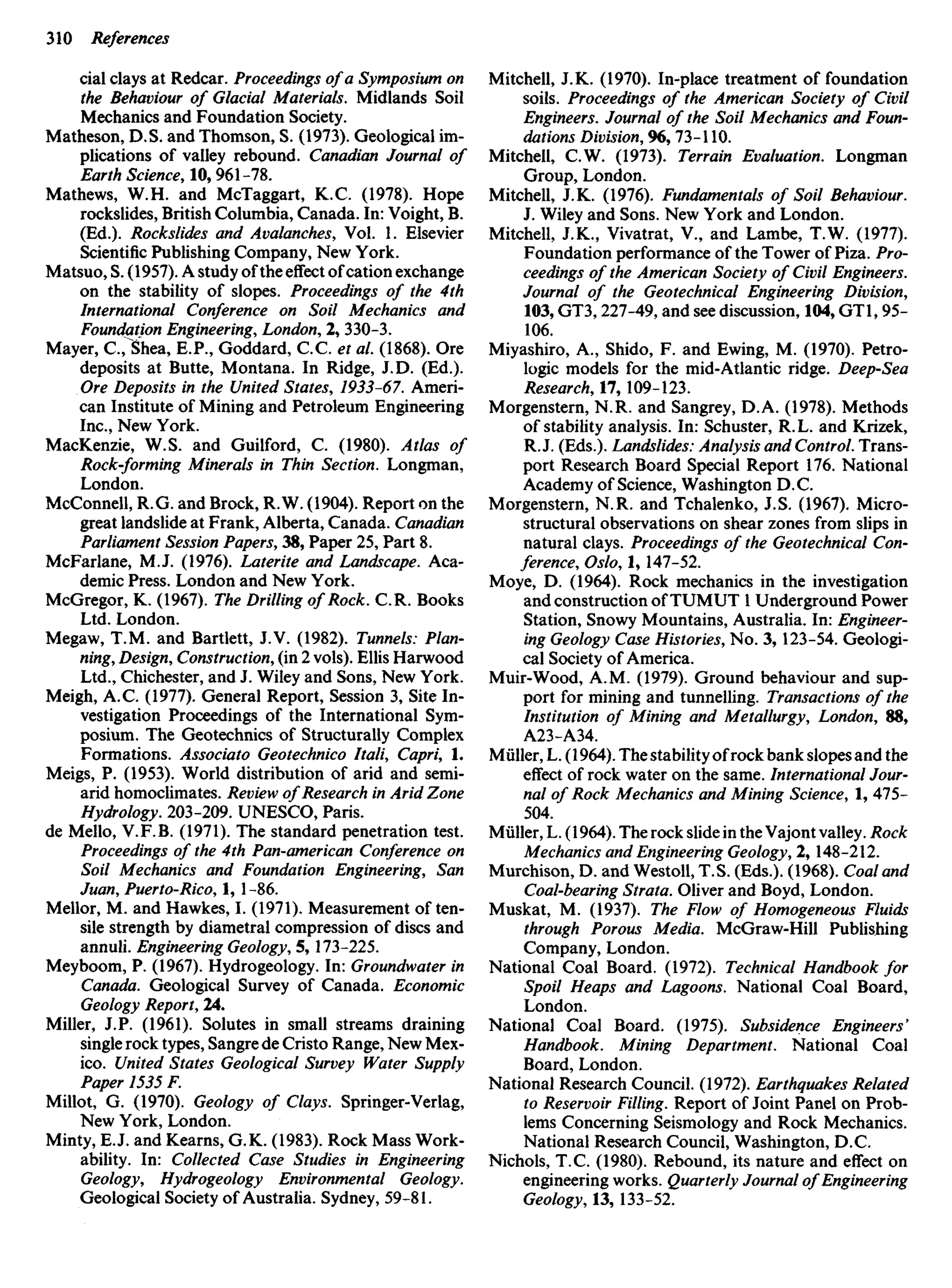

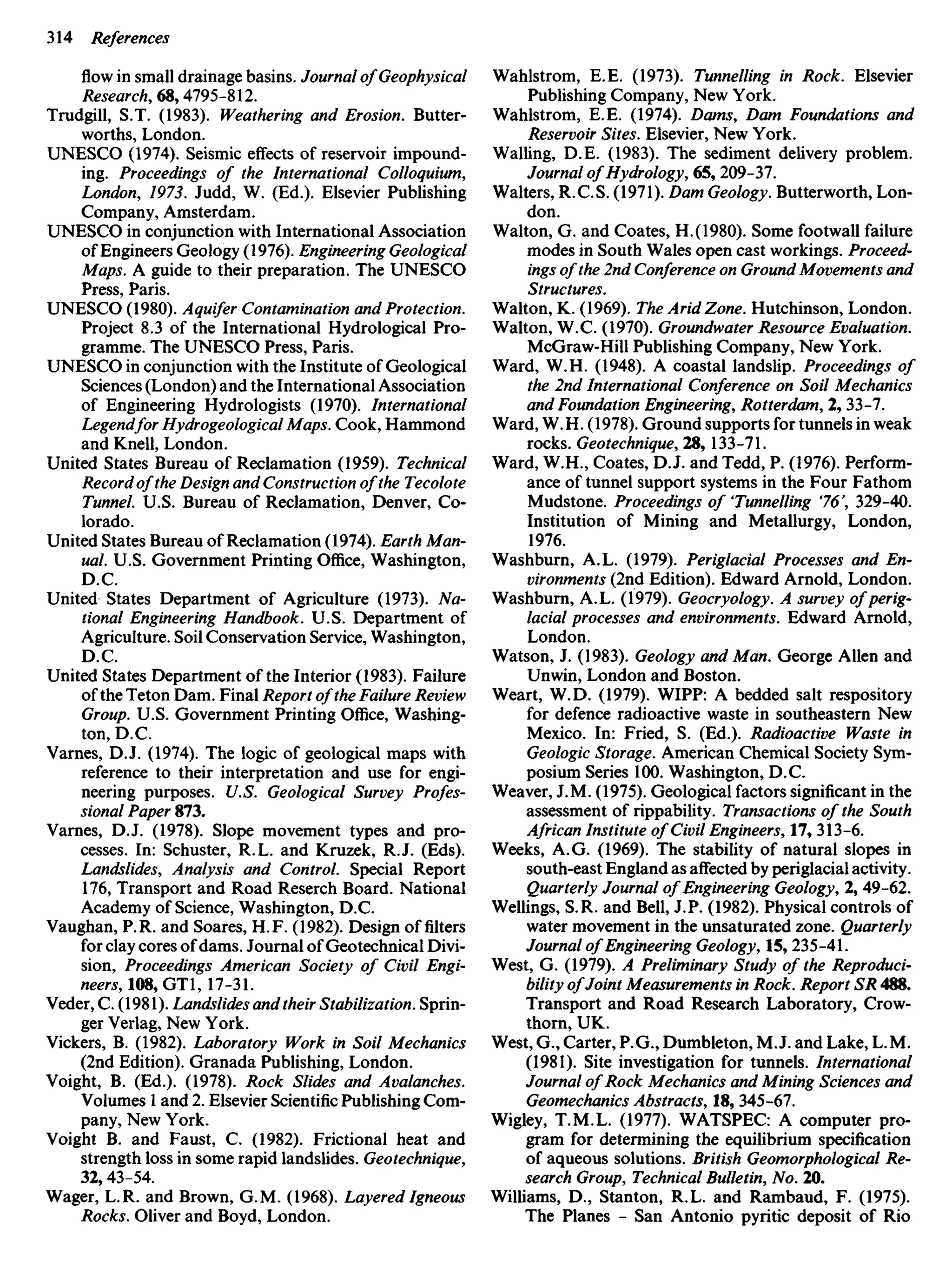

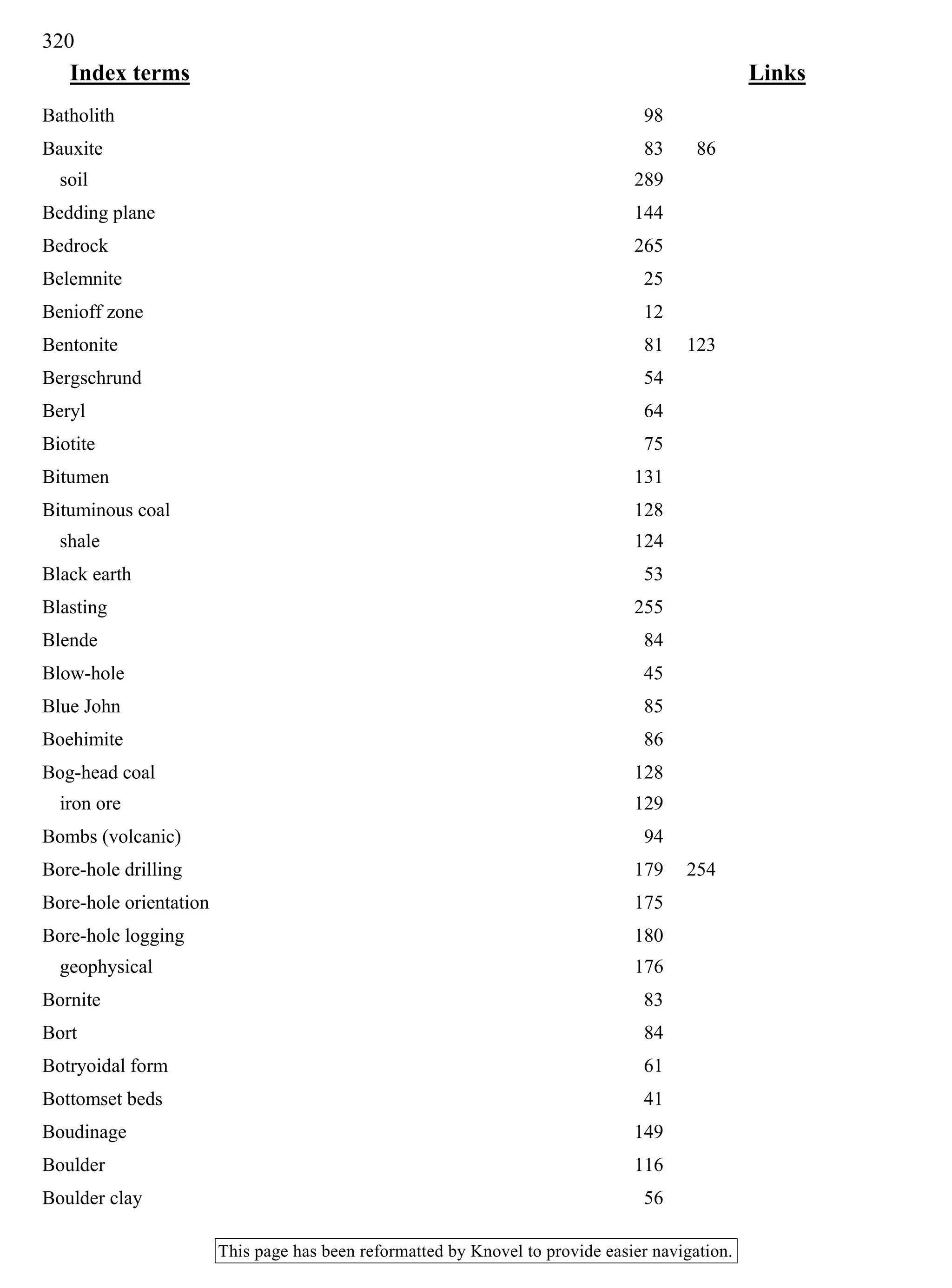

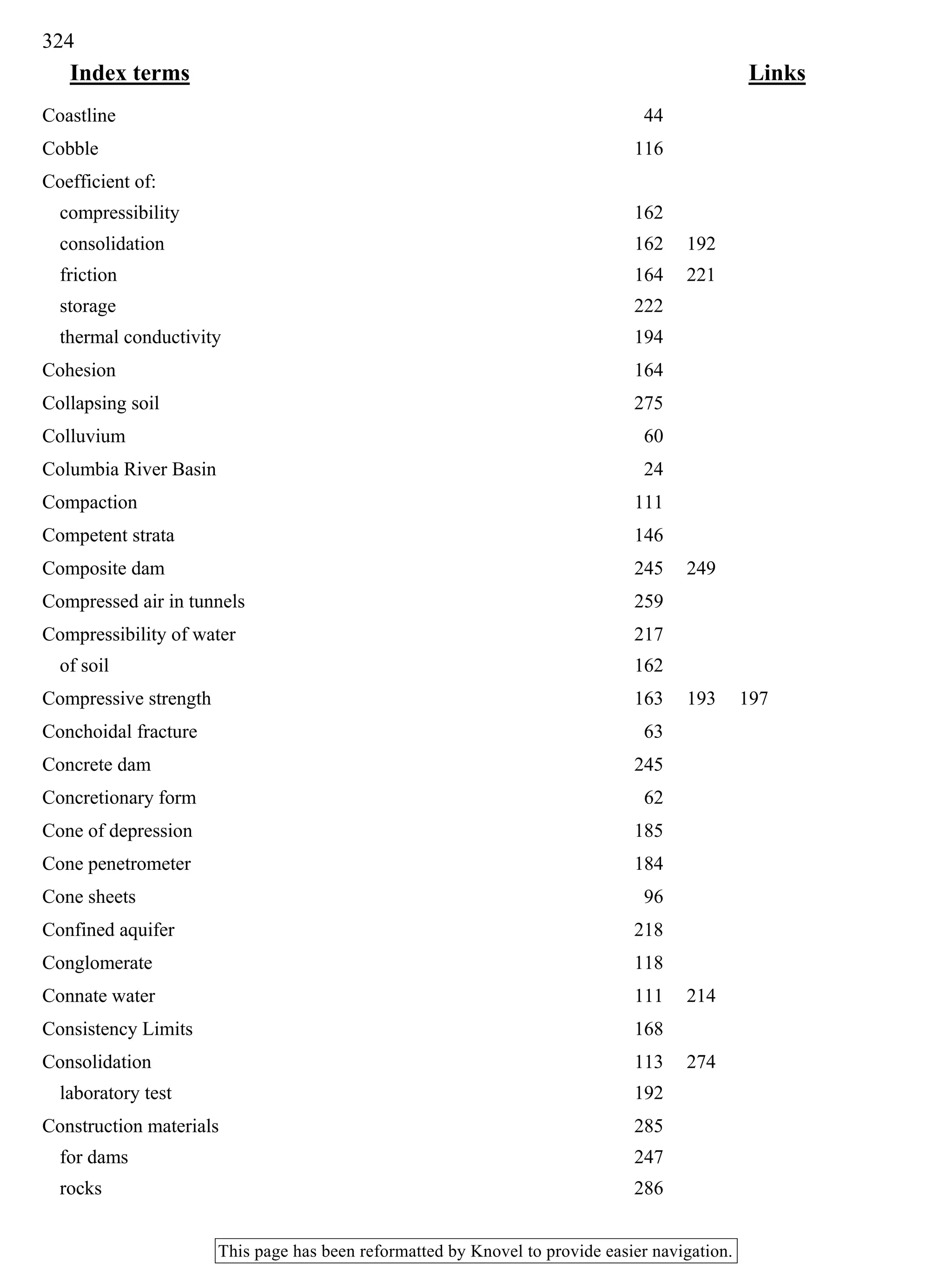

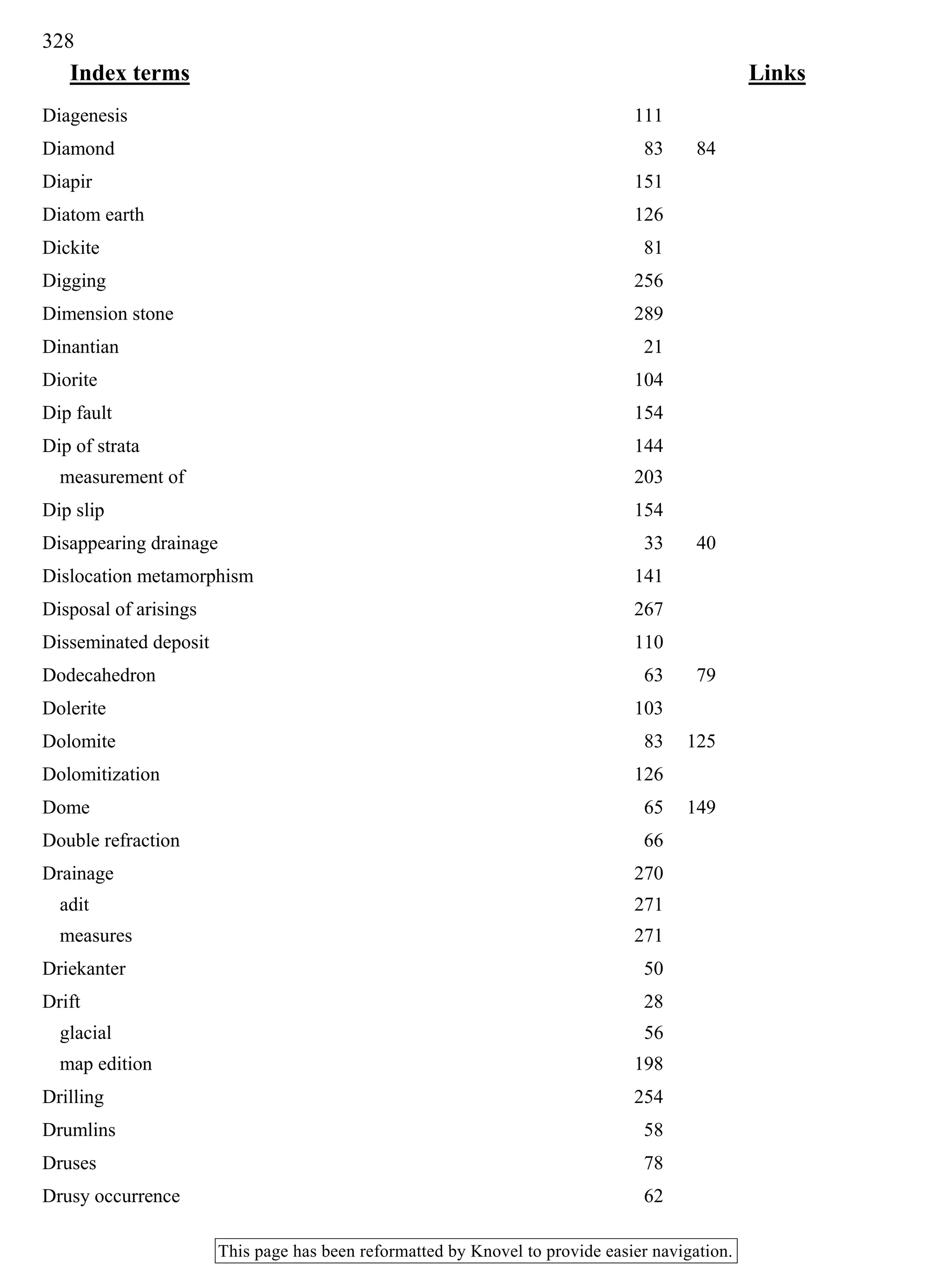

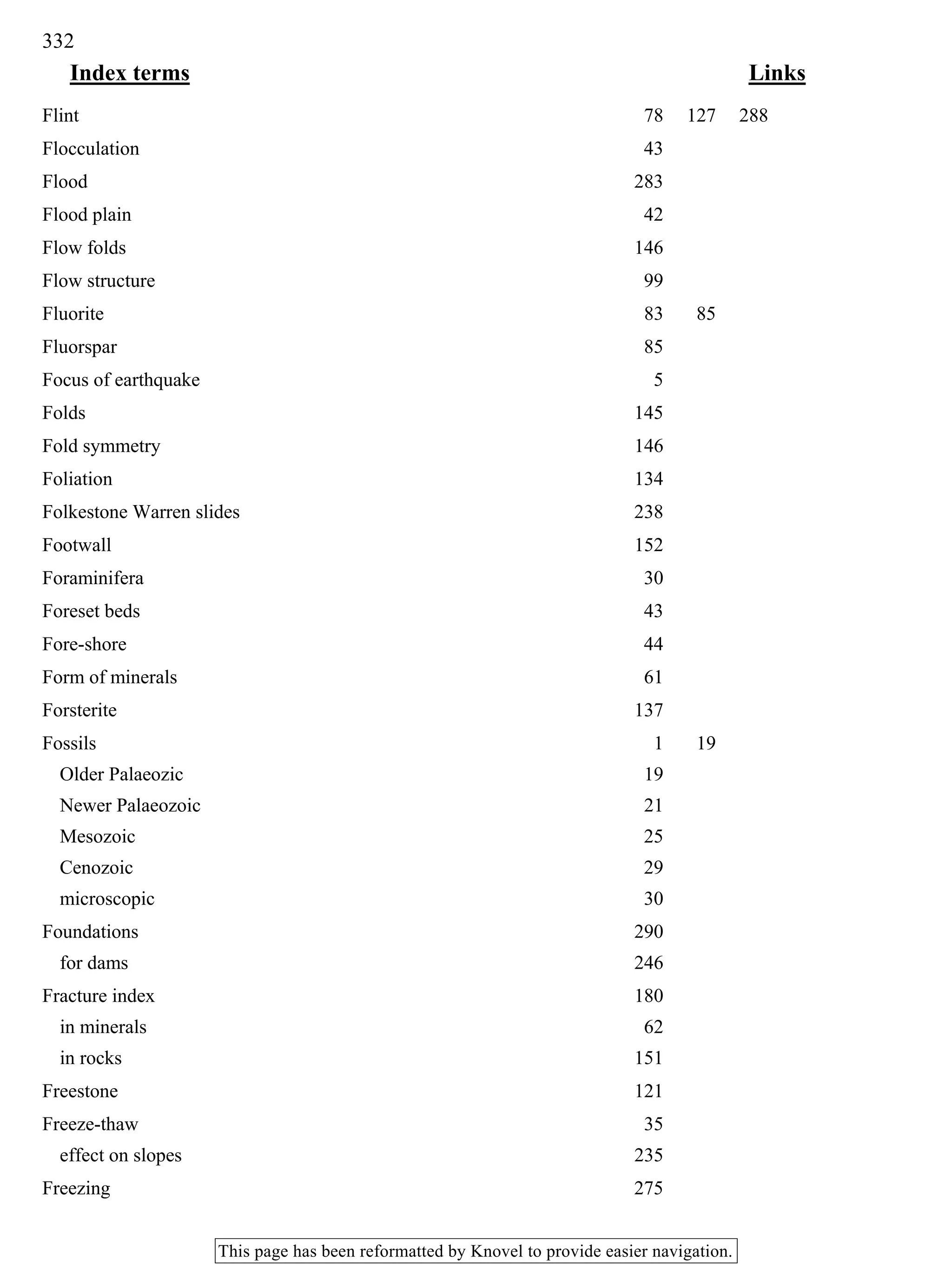

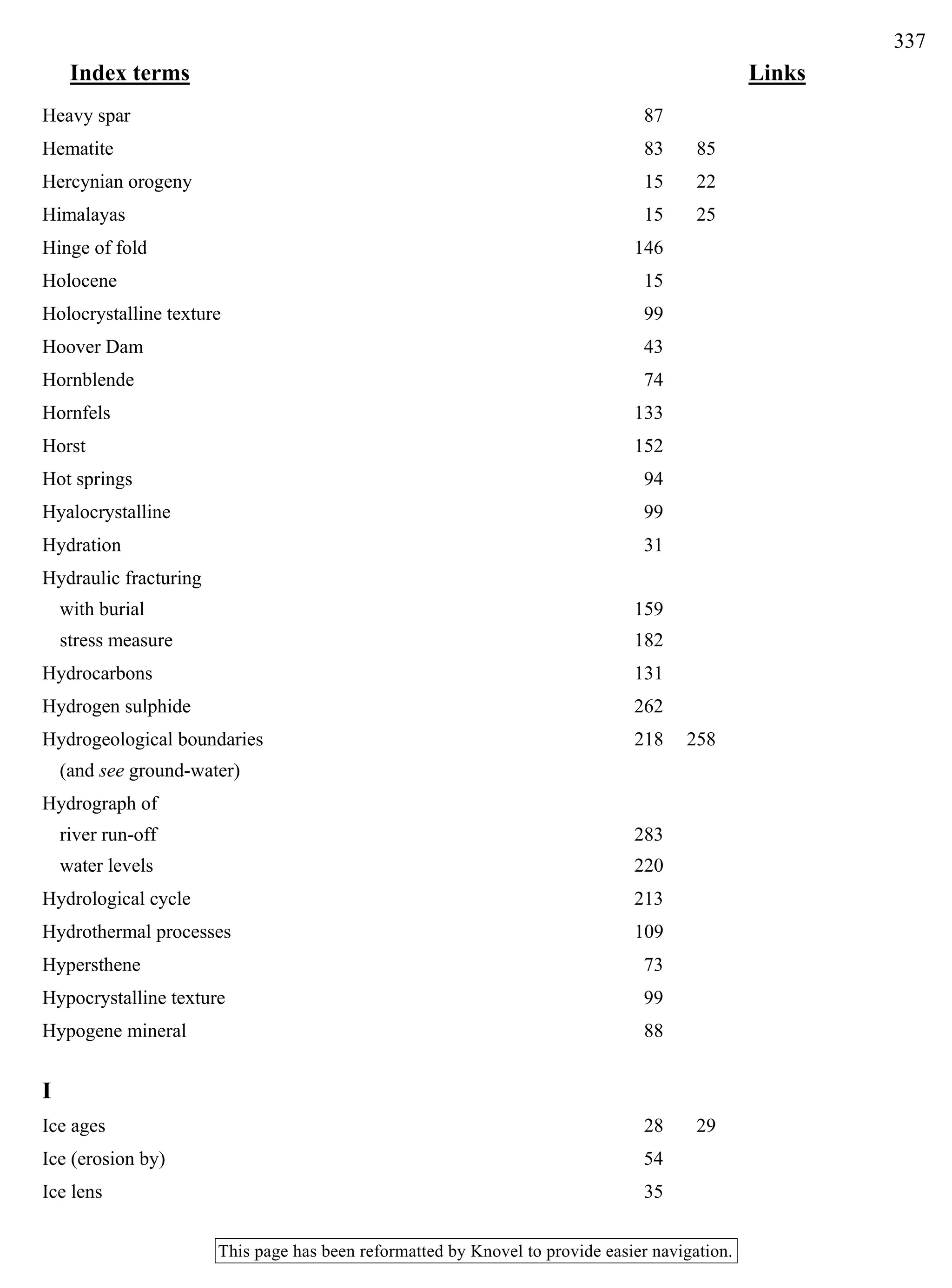

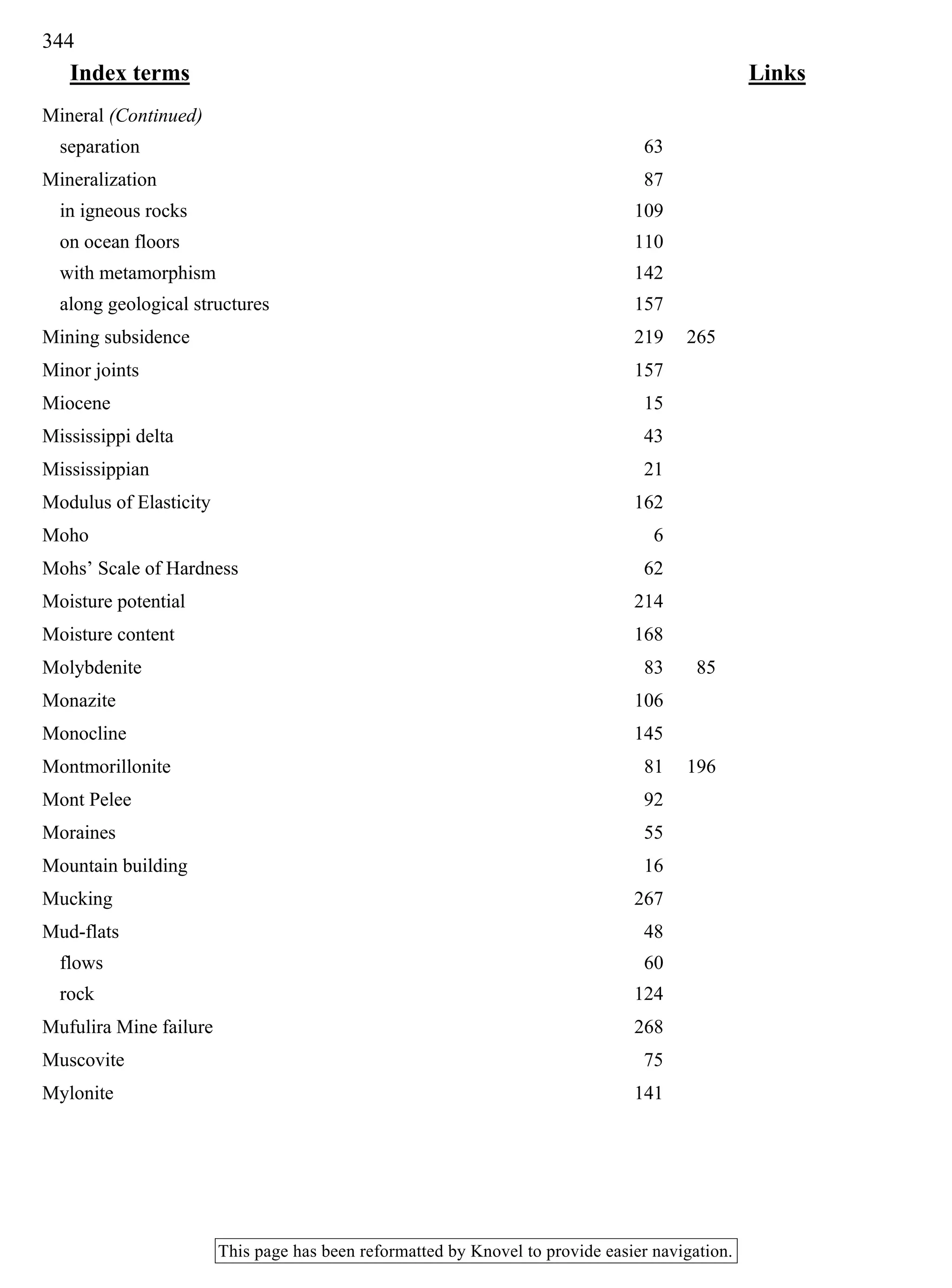

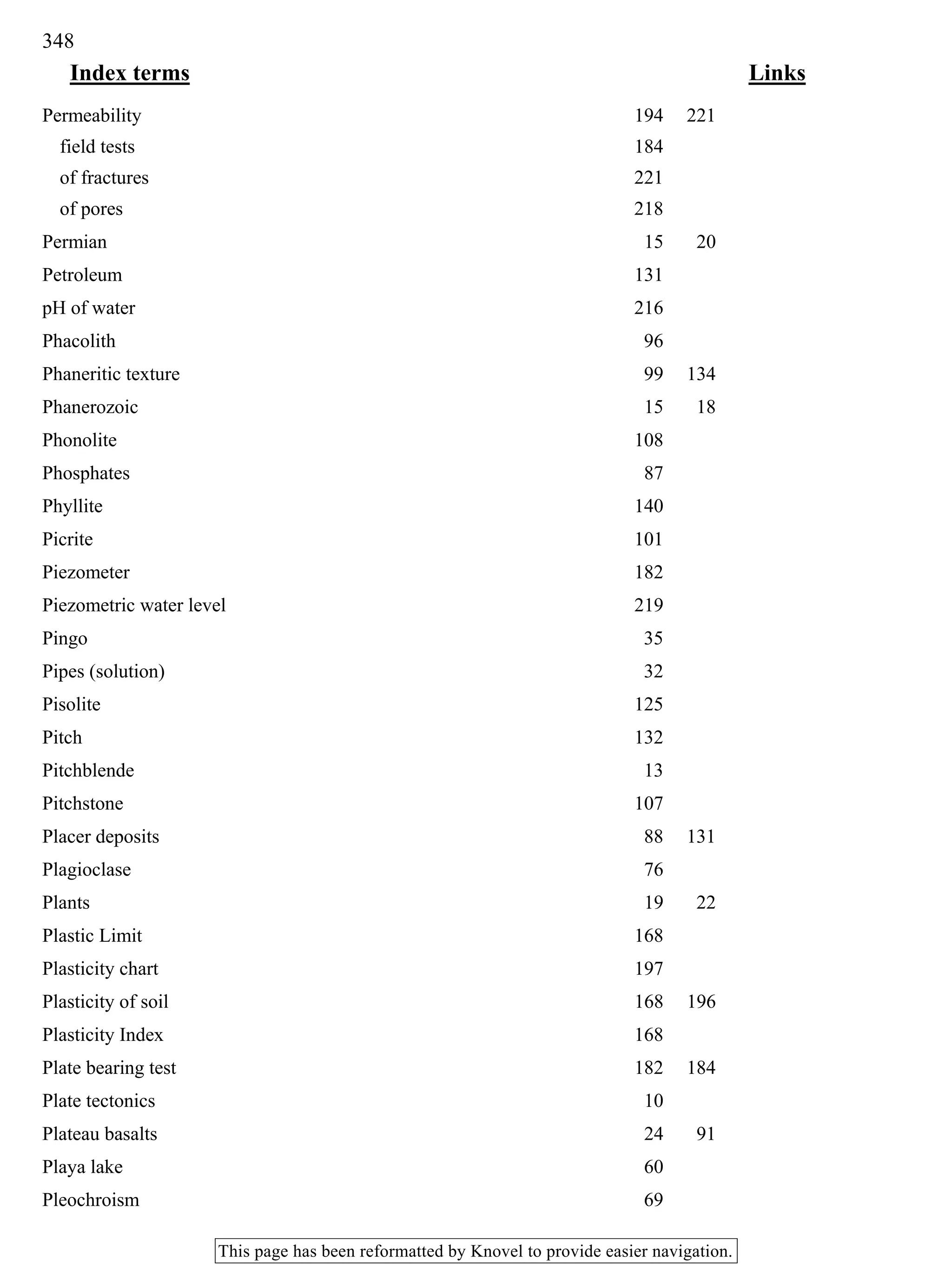

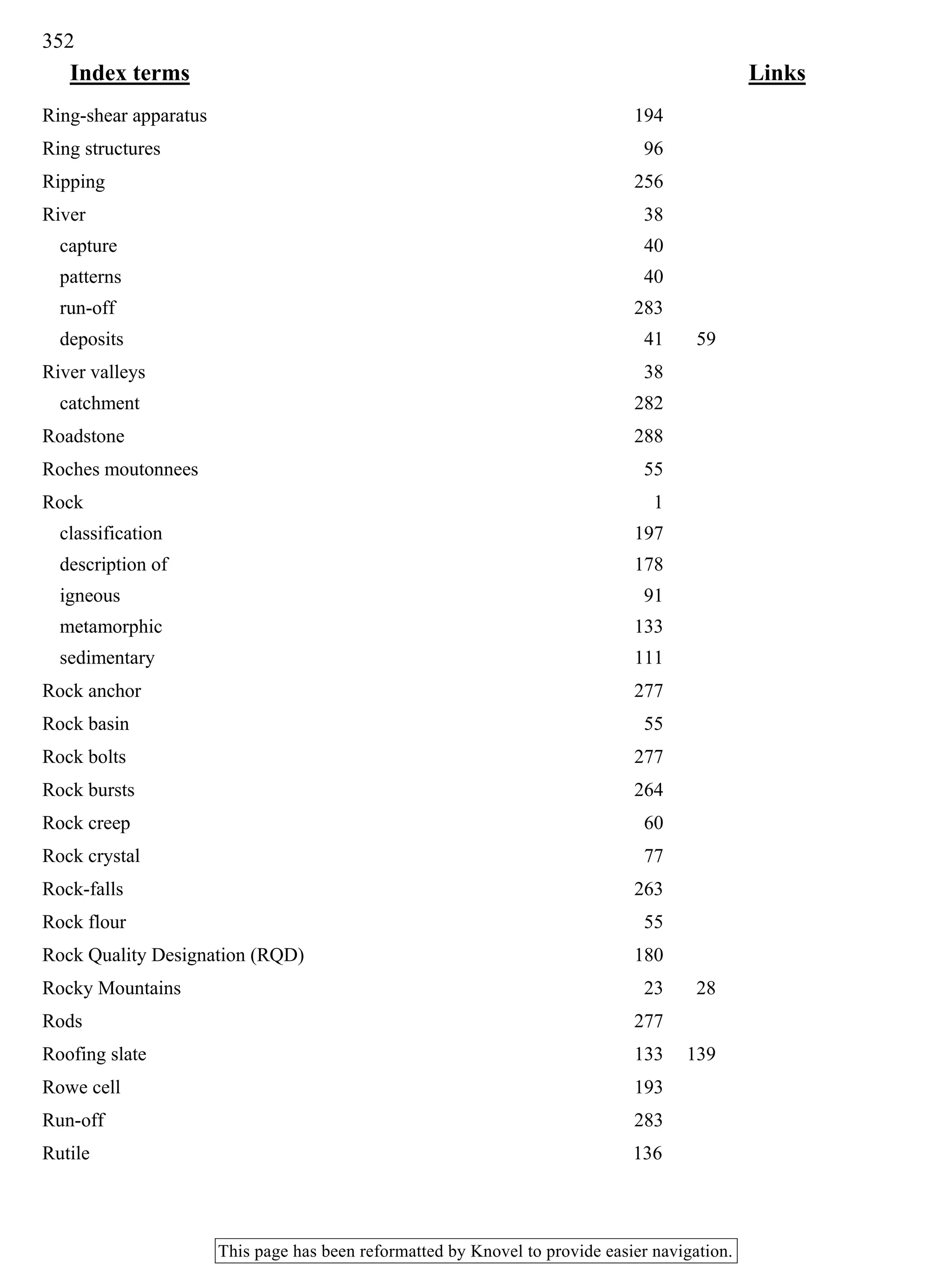

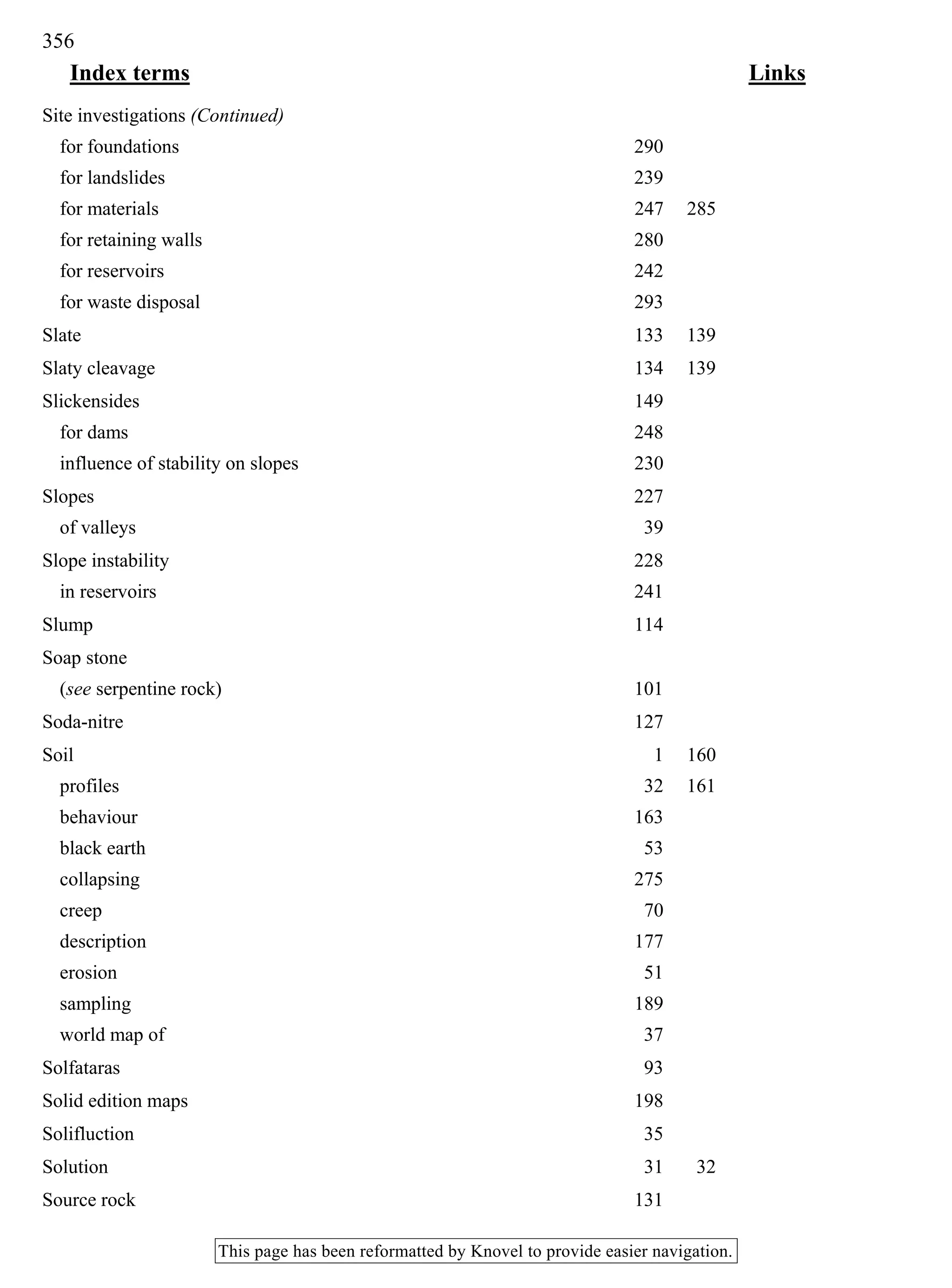

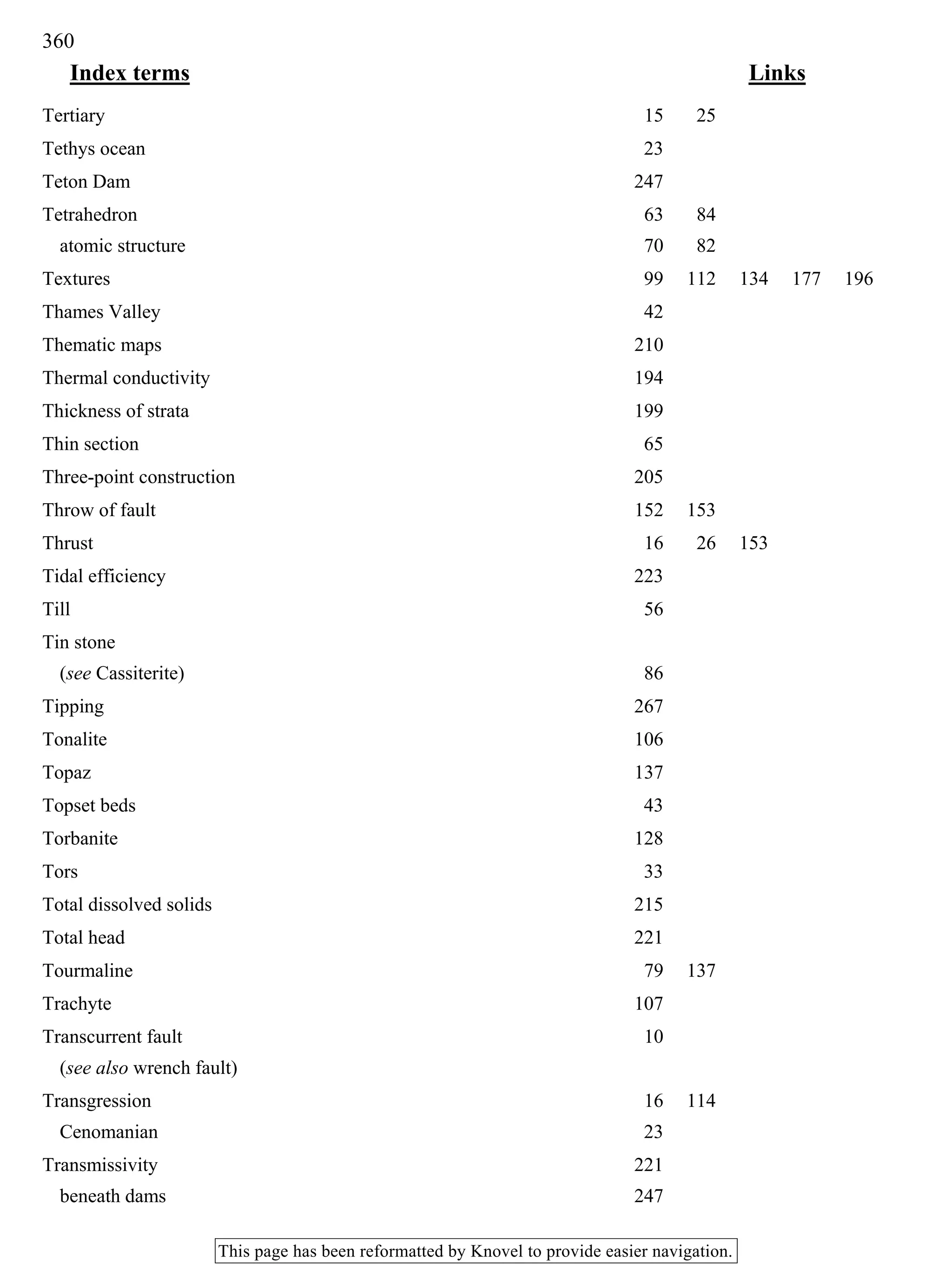

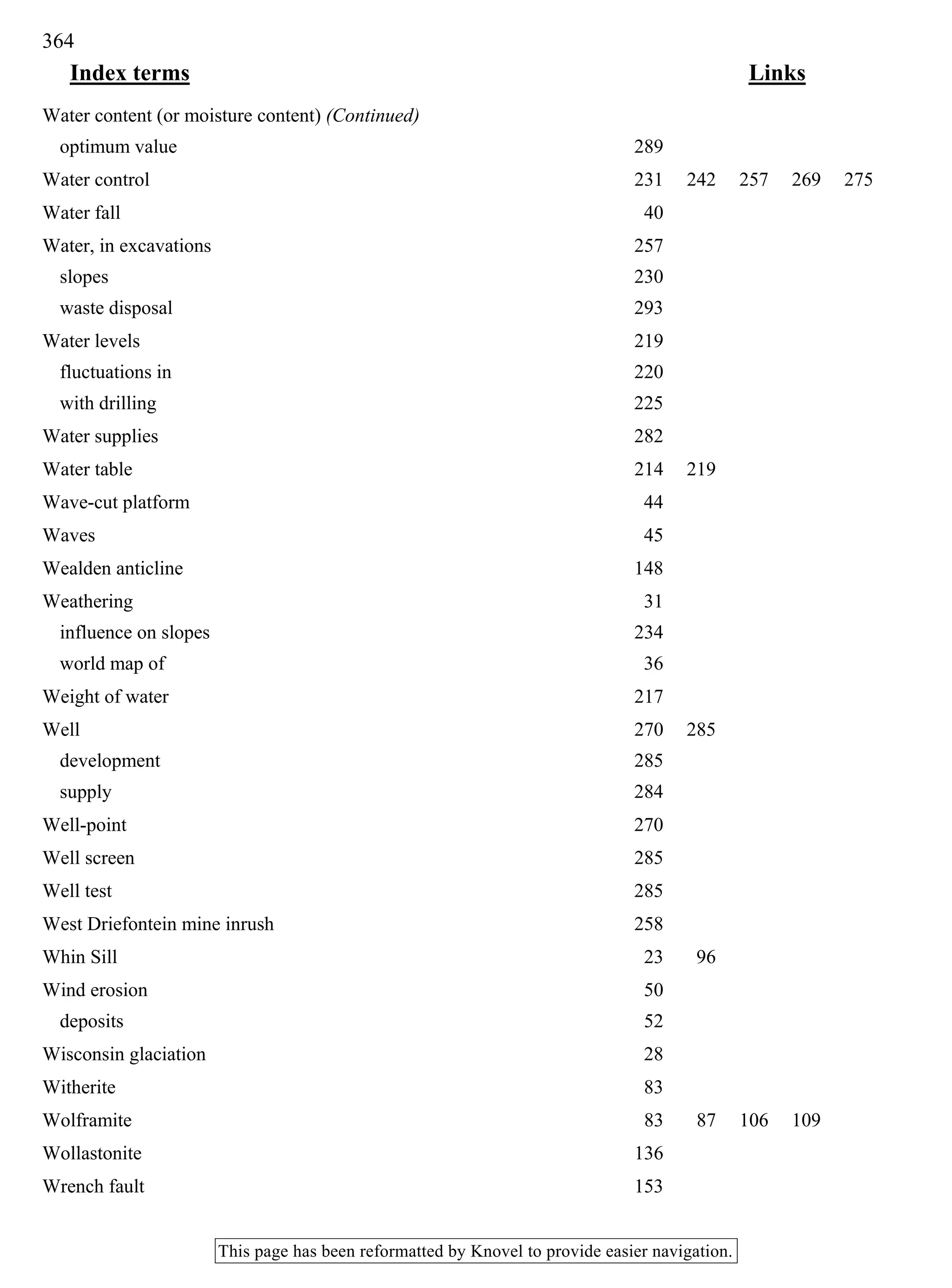

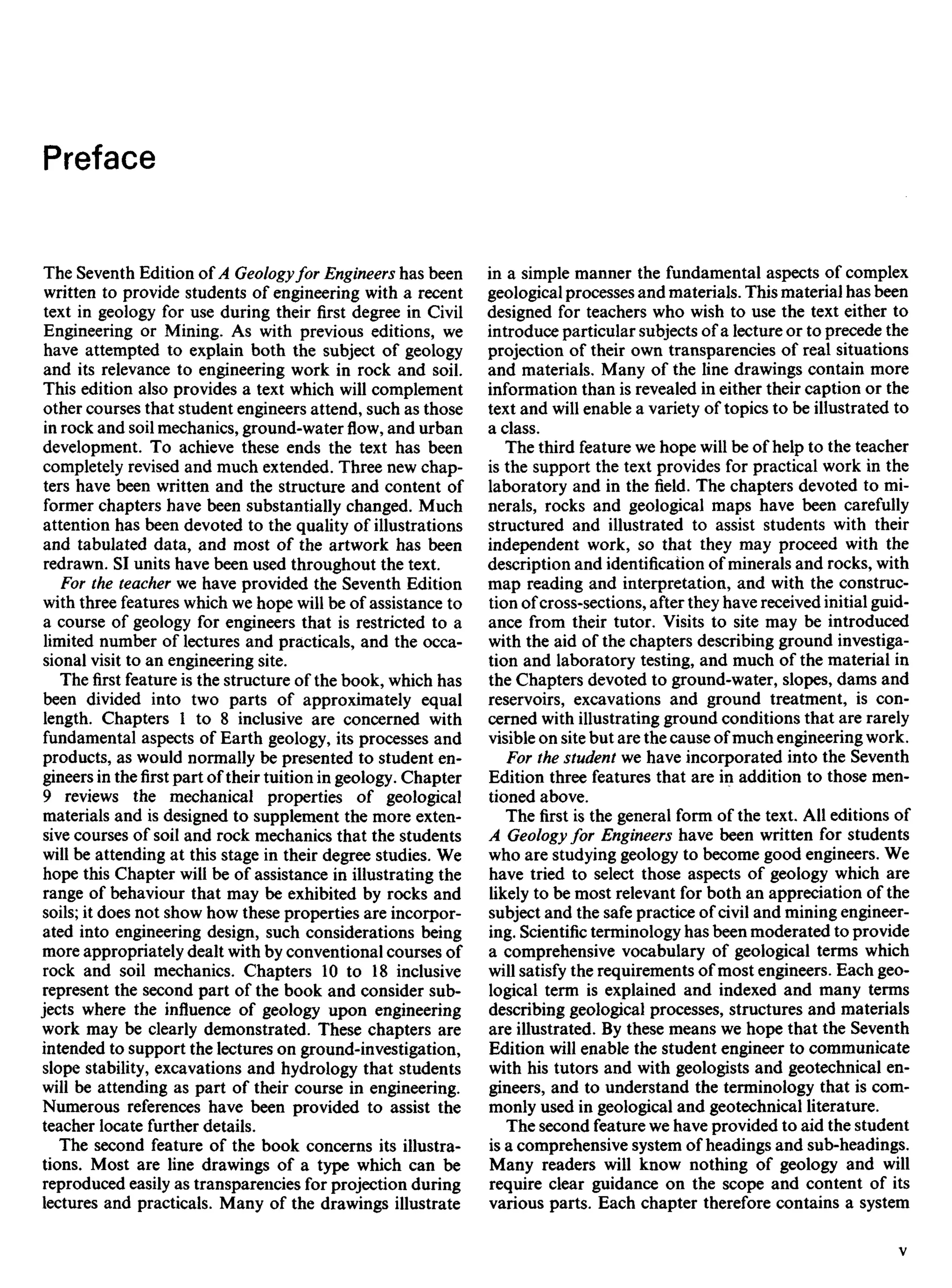

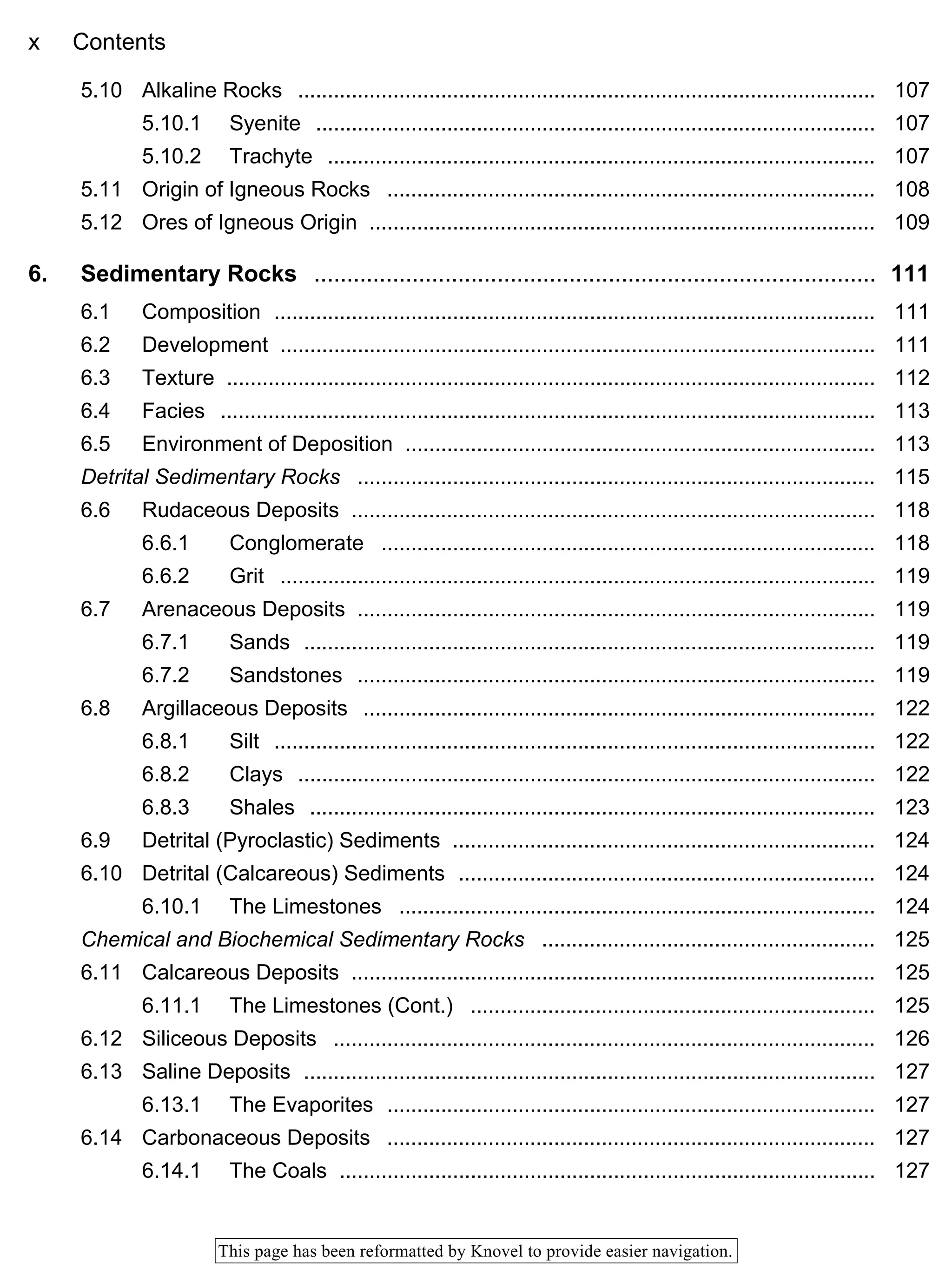

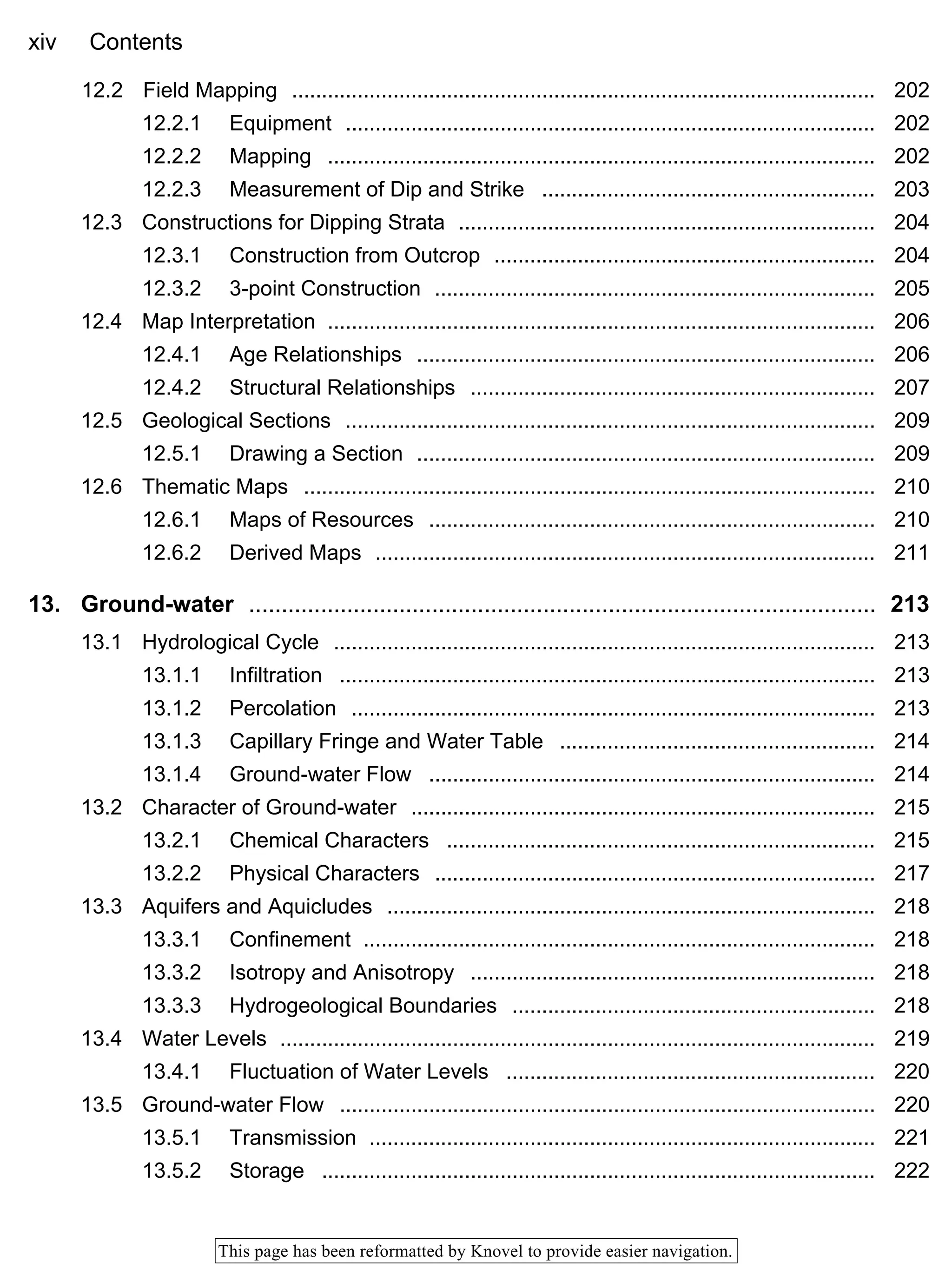

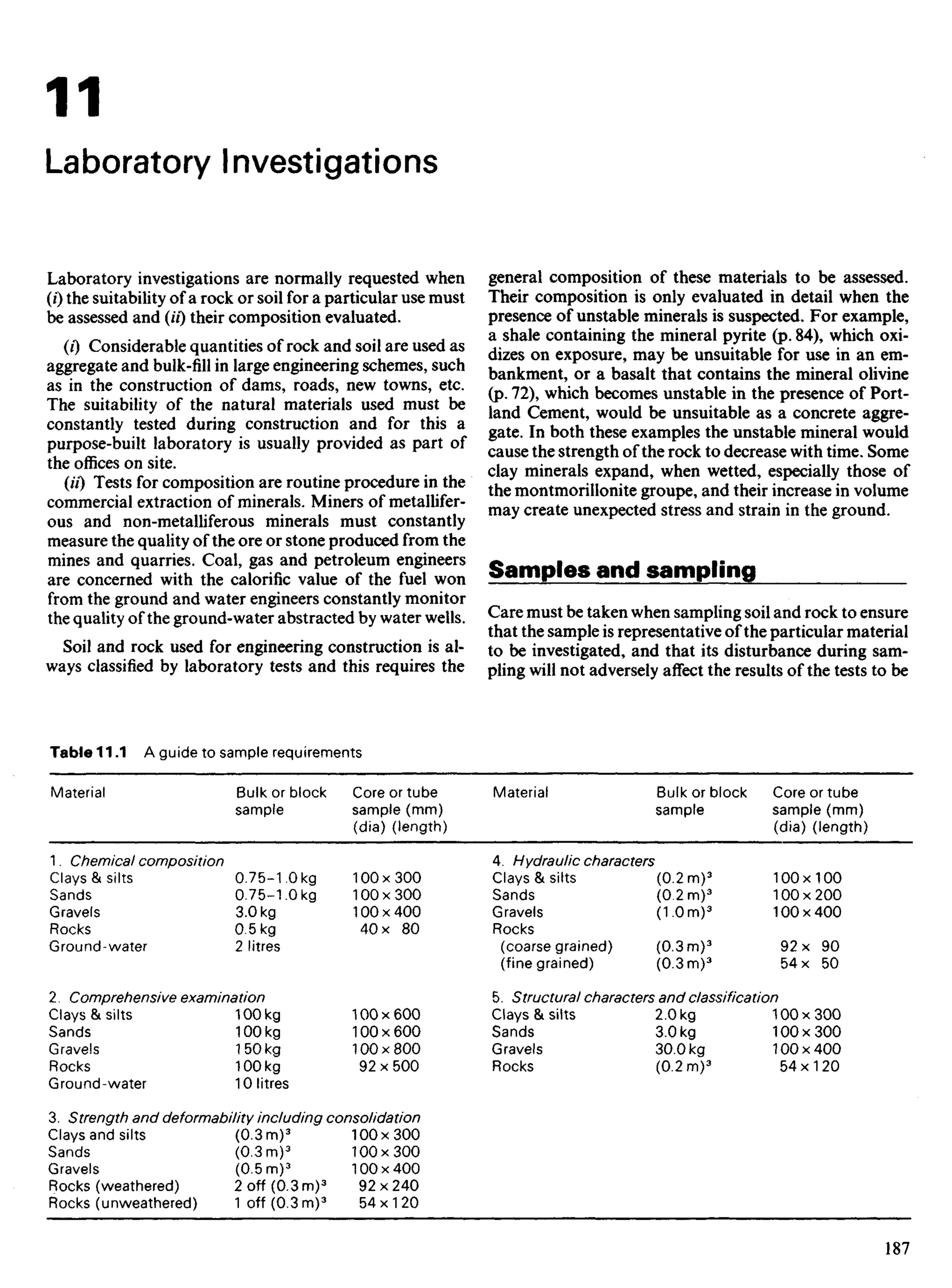

![performed upon it (see Brorns, 1980 and Amer. Soc.

Testing Materials, 1970). No sample can be collected

without it being disturbed in some way, for the reasons

explained in Chapter 9,

In practice two categories of sample may be obtained:

(0 Routine sample, i.e. one slightly disturbed but col-

lected with reasonable care by experienced staff who

should ensure that it suffers no avoidable change in mois-

ture content, does not lose any of its constituents (e.g.

fine sand from mixed gravel) and is not deformed by

careless handling if its strength or permeability are to be

measured. Routine samples must be correctly stored and

adequately labelled. Table 11.1 provides a guide to sam-

ple requirements.

(U) Research sample, i.e. one collected with the great-

est care possible, often using expensive procedures to

reduce disturbance: such a sample cannot be economic-

ally provided by commercial routine sampling.

The difficulties of obtaining routine samples using con-

ventional methods of commercial sampling are illustrated

by Kallstenius (1963) and Rowe (1972).

Guidelines

The following guidelines should be observed when pos-

sible and considered the minimum standard required for

routine sampling.

Selection of samples

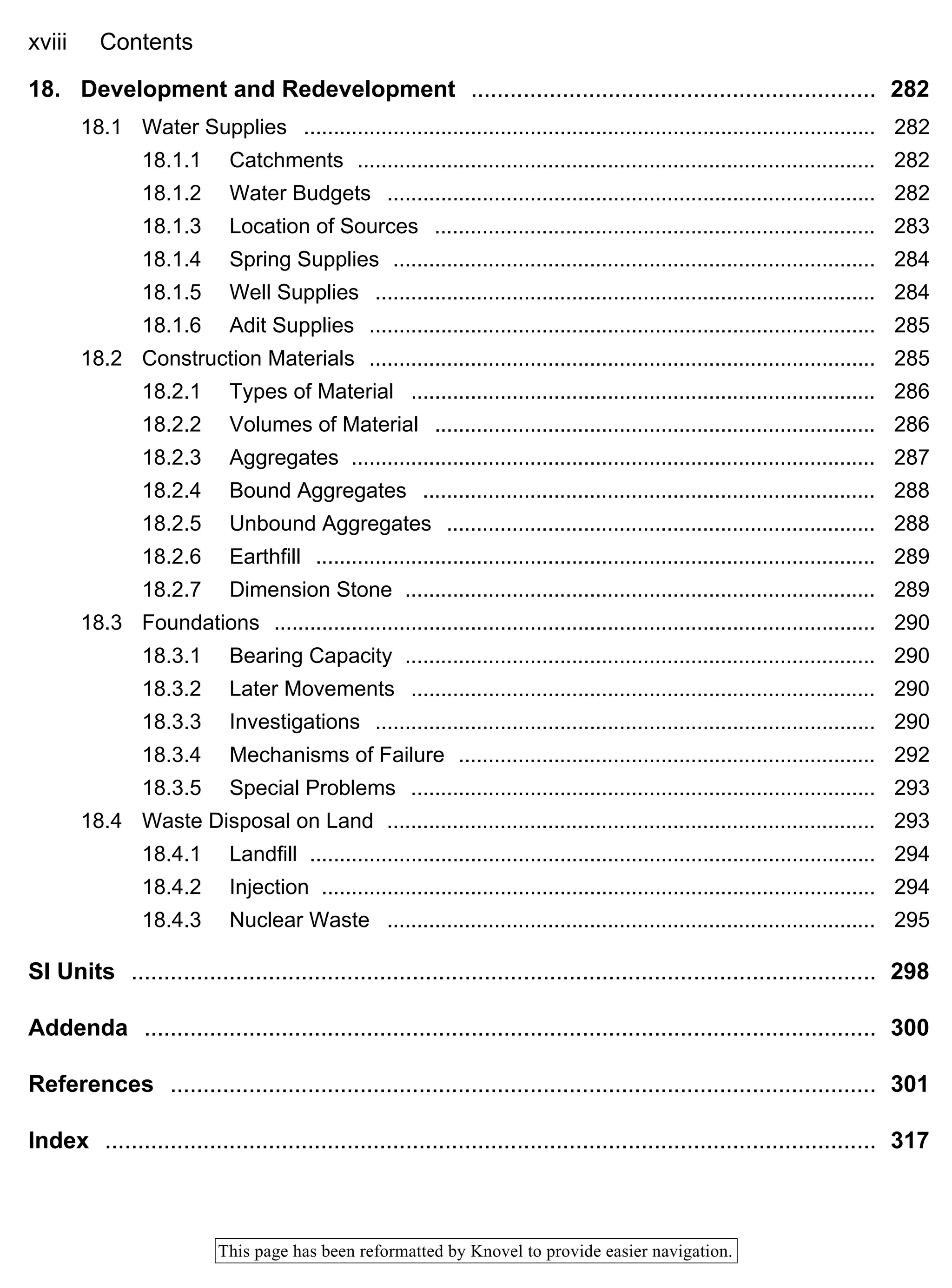

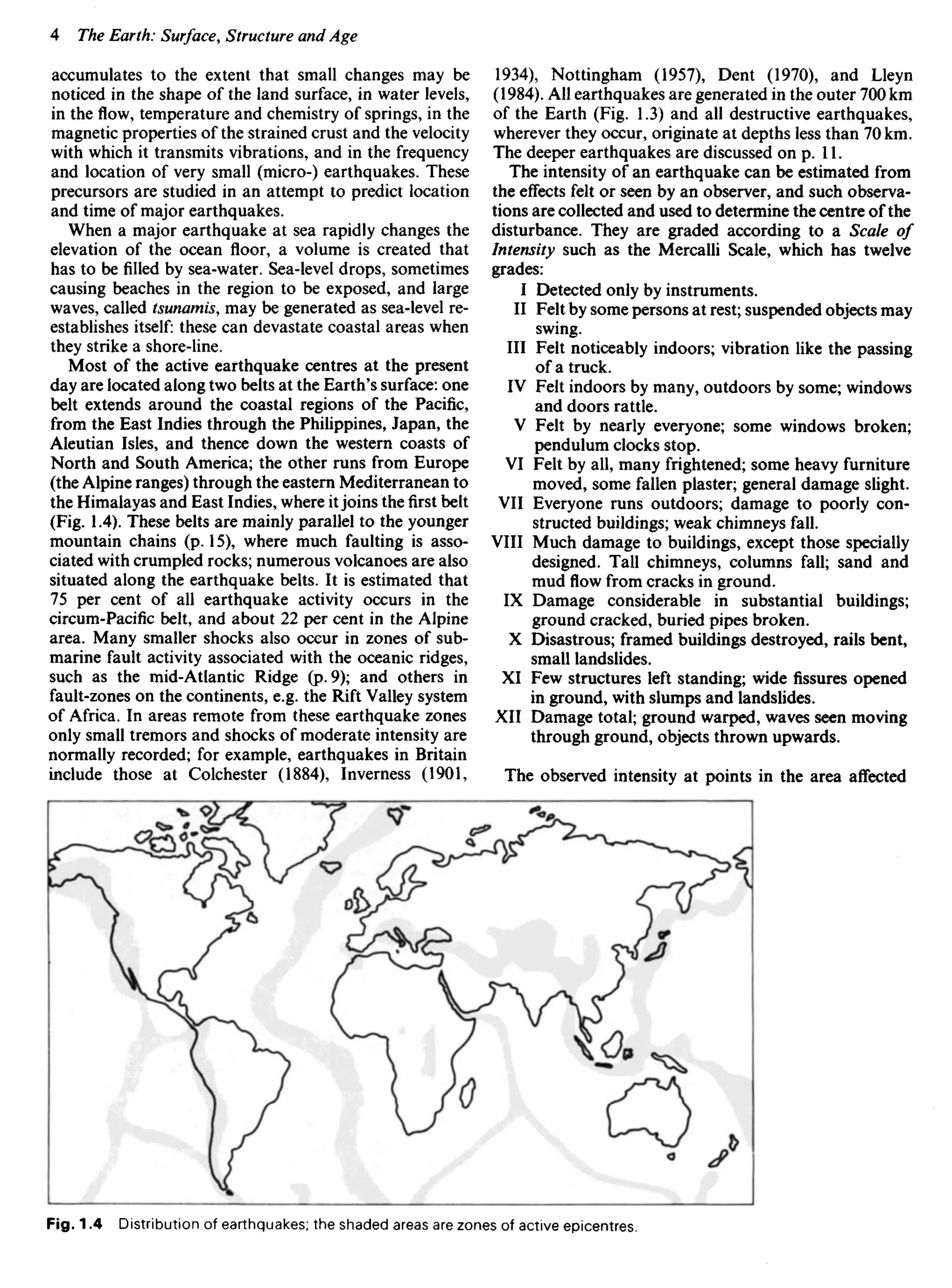

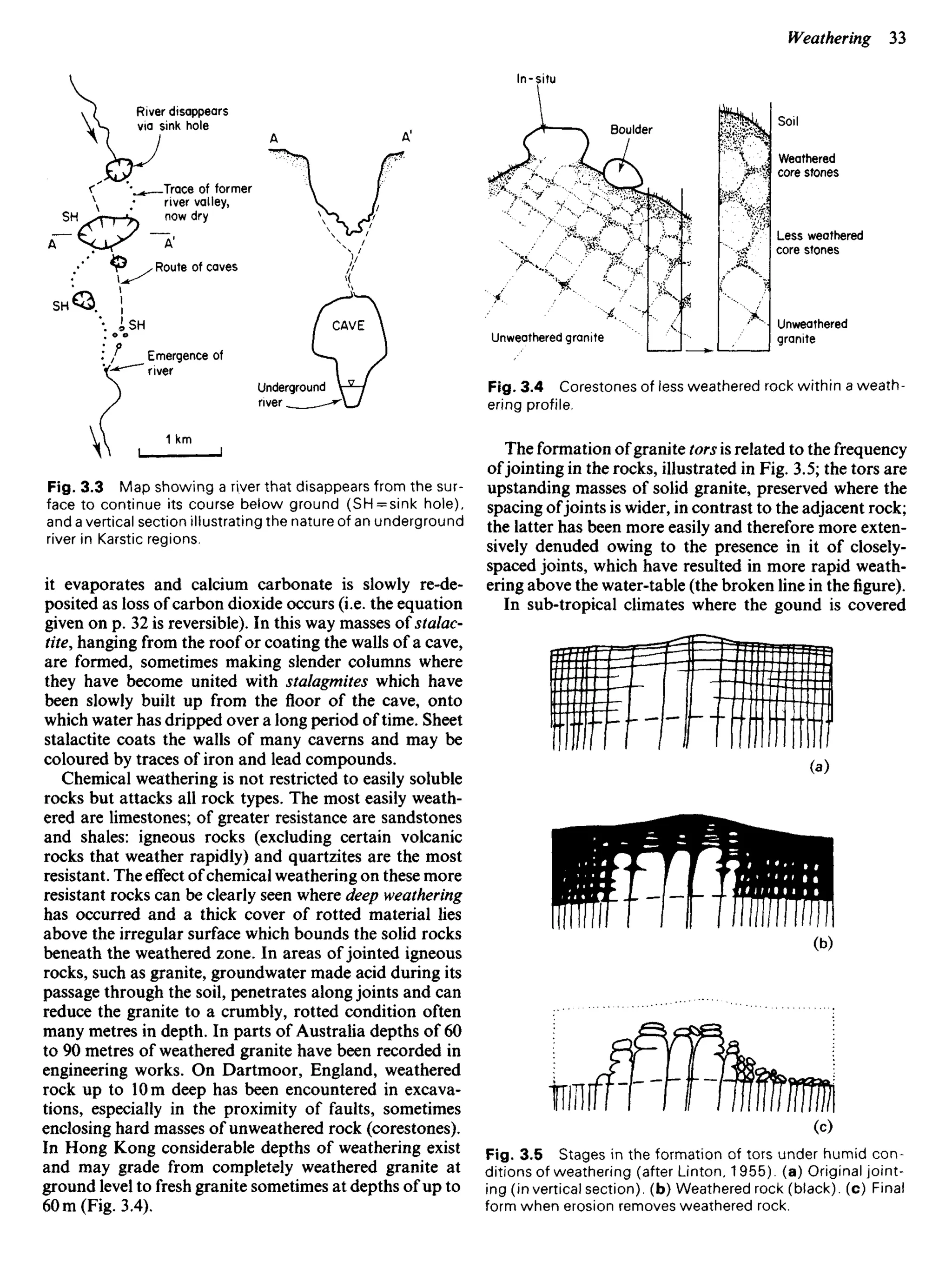

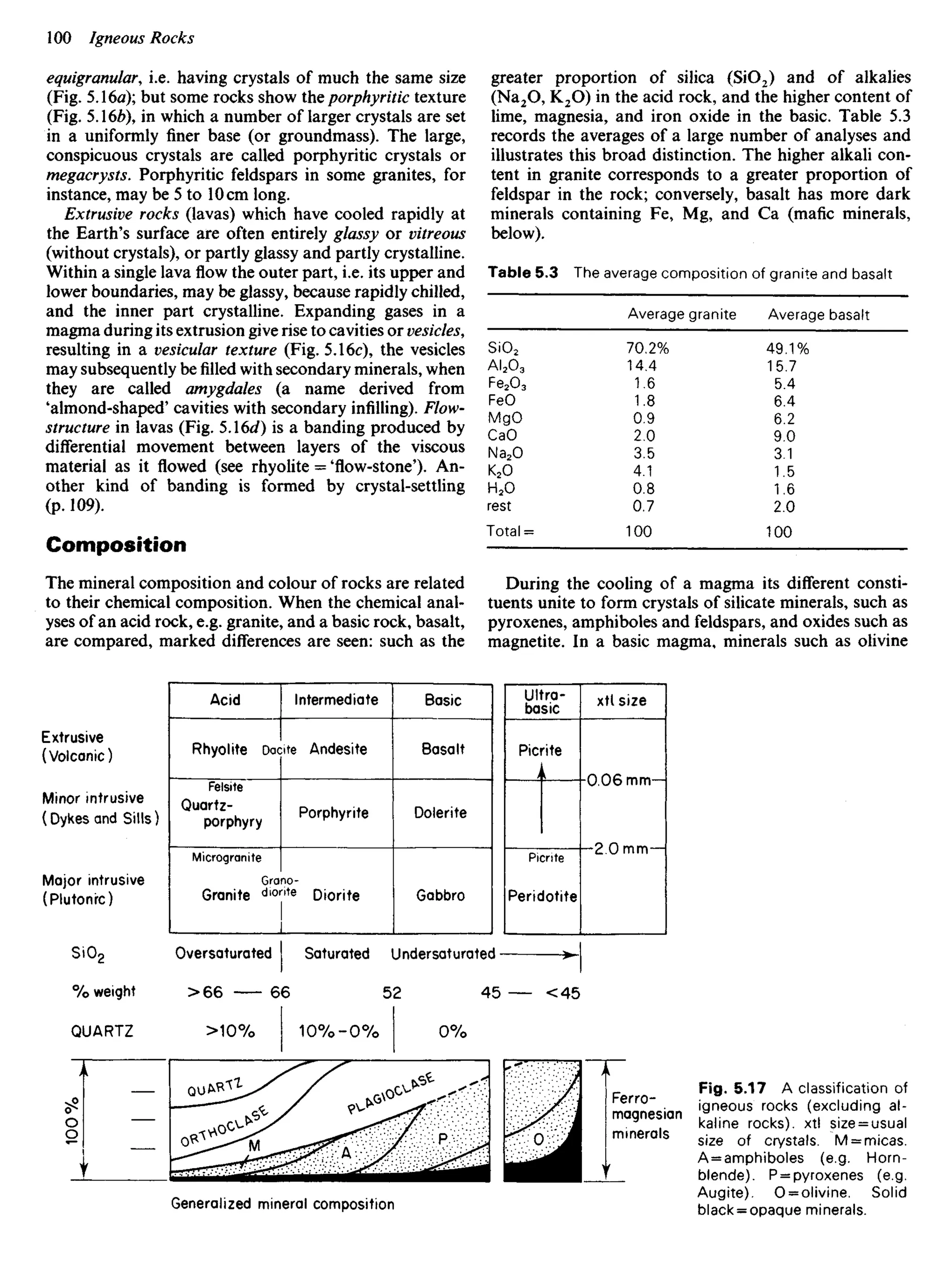

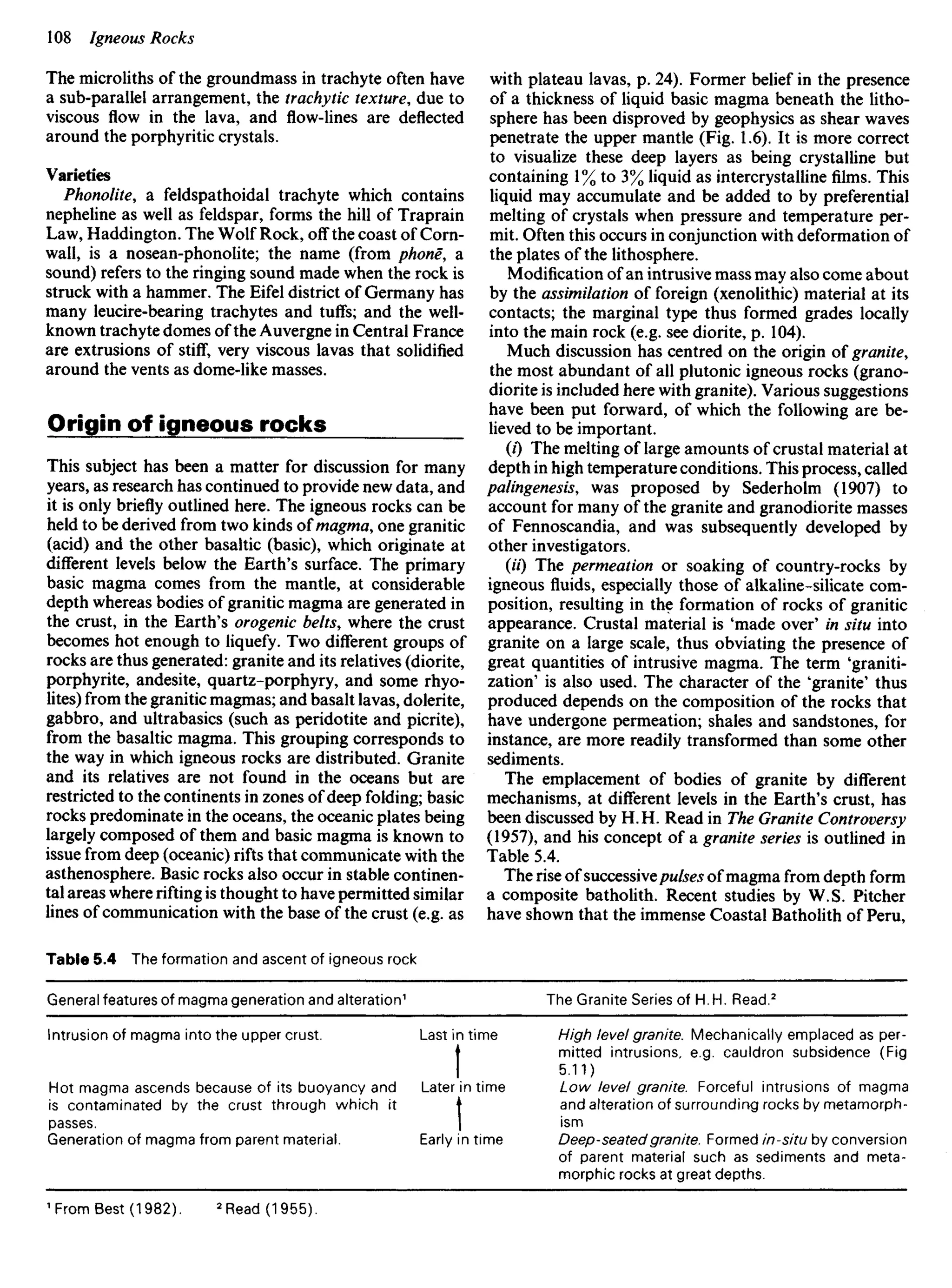

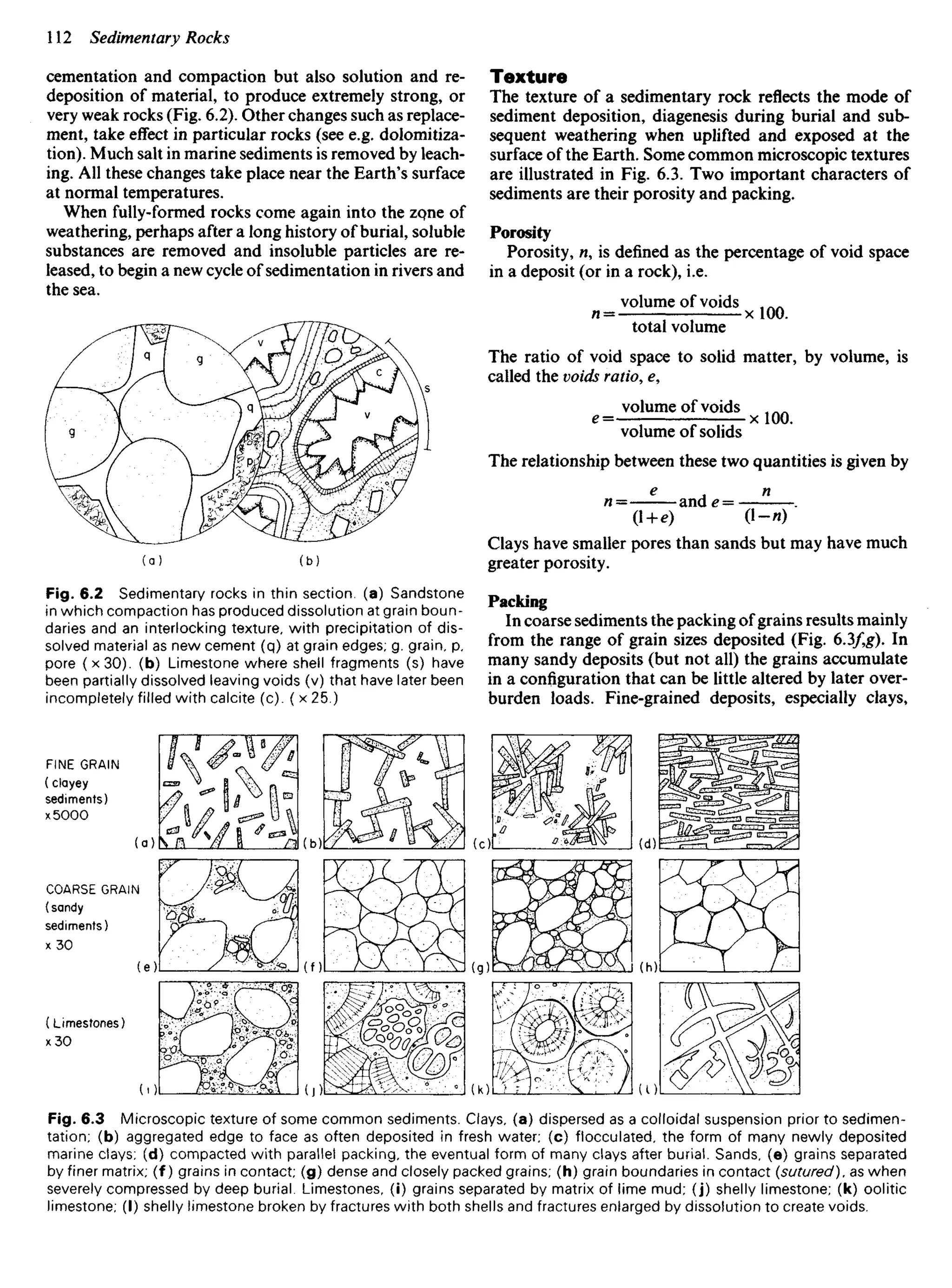

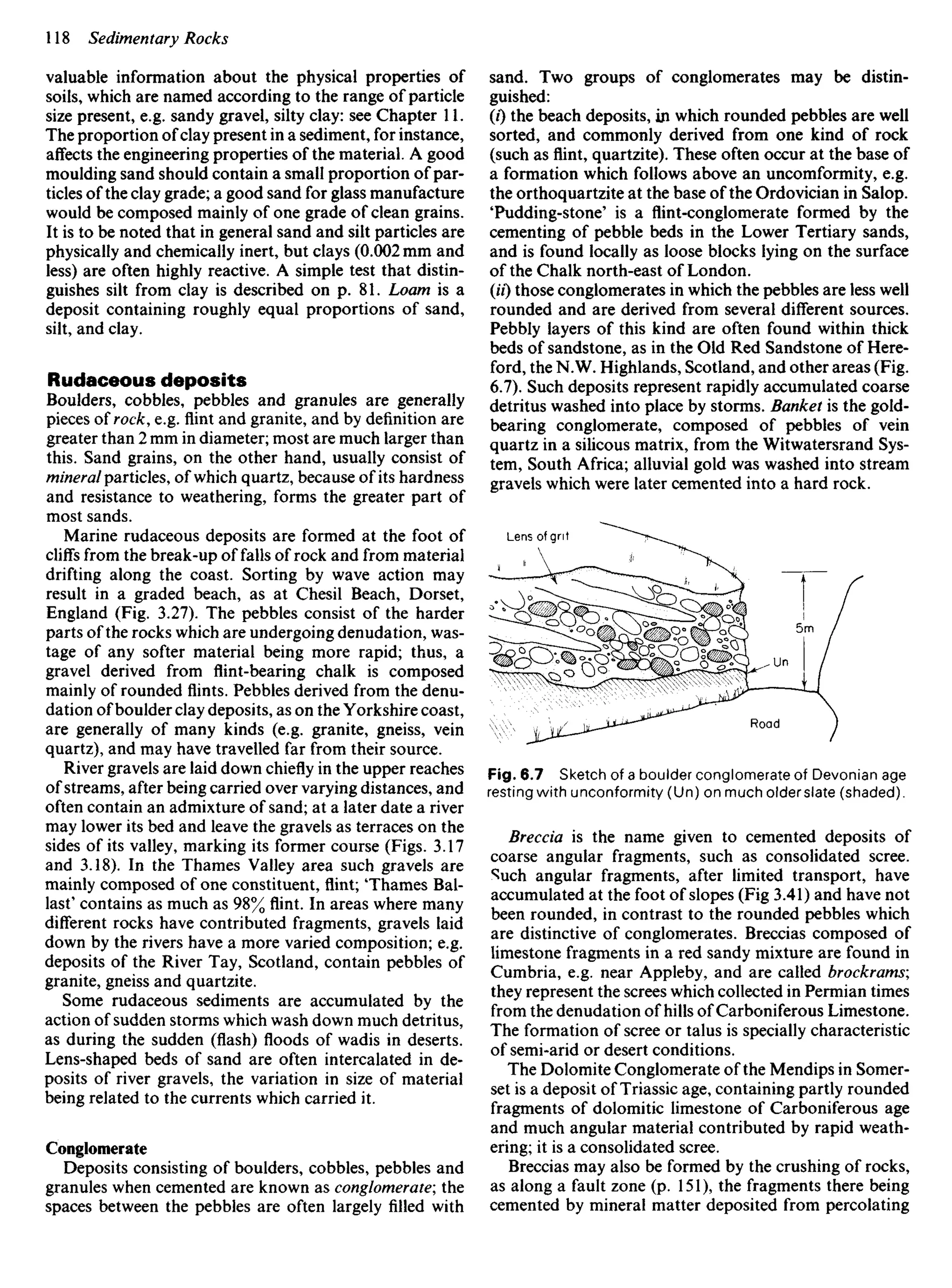

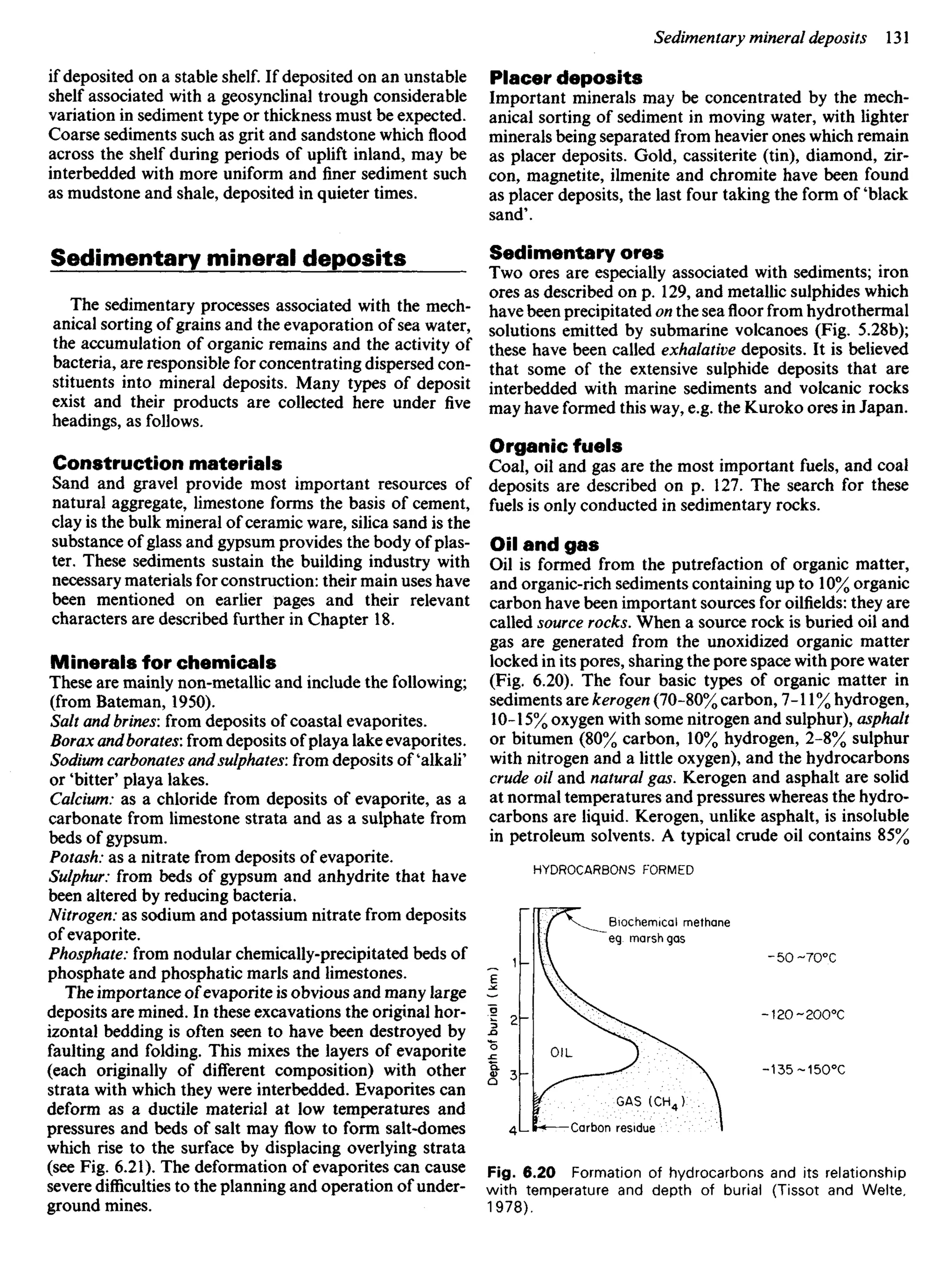

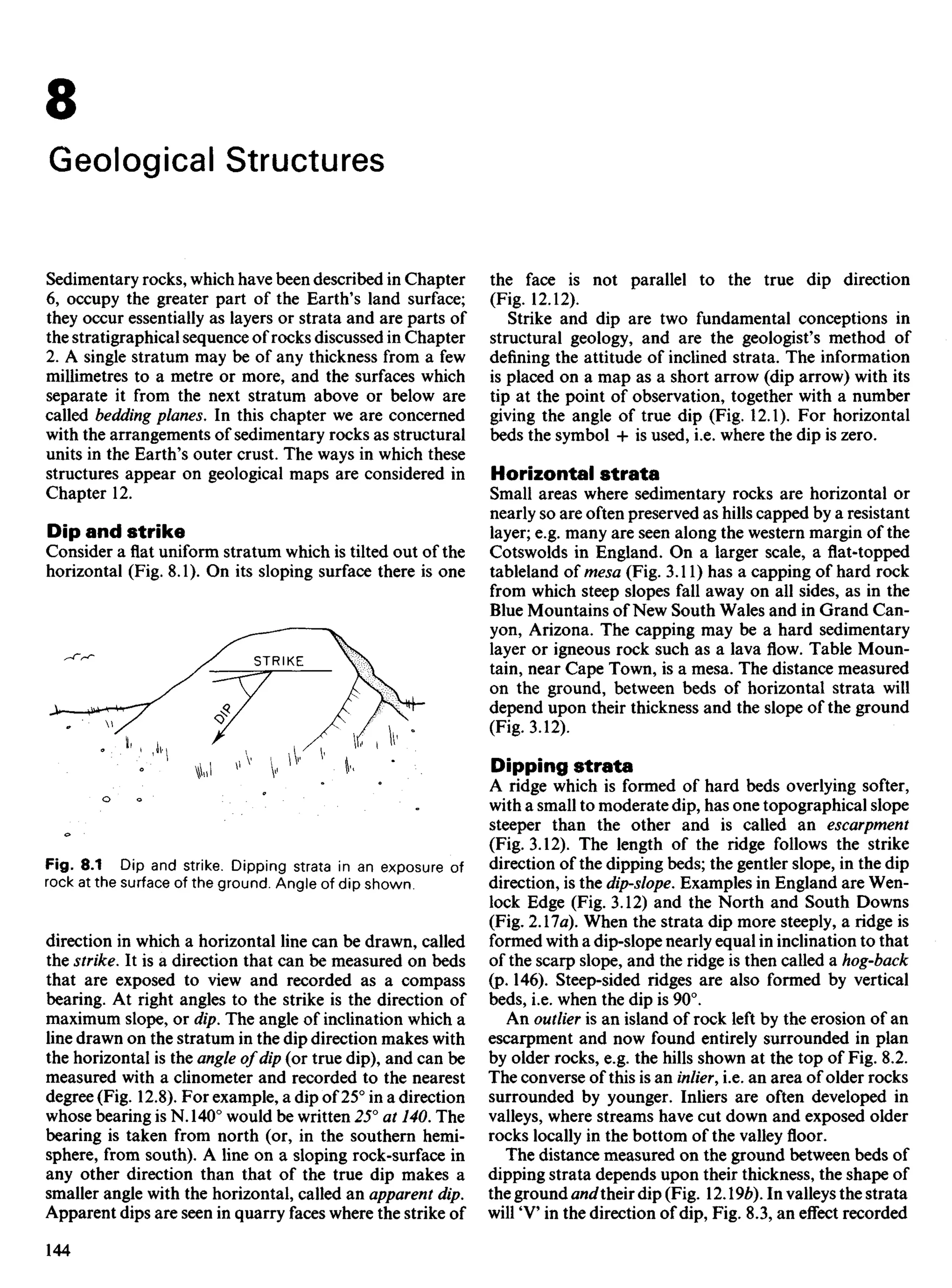

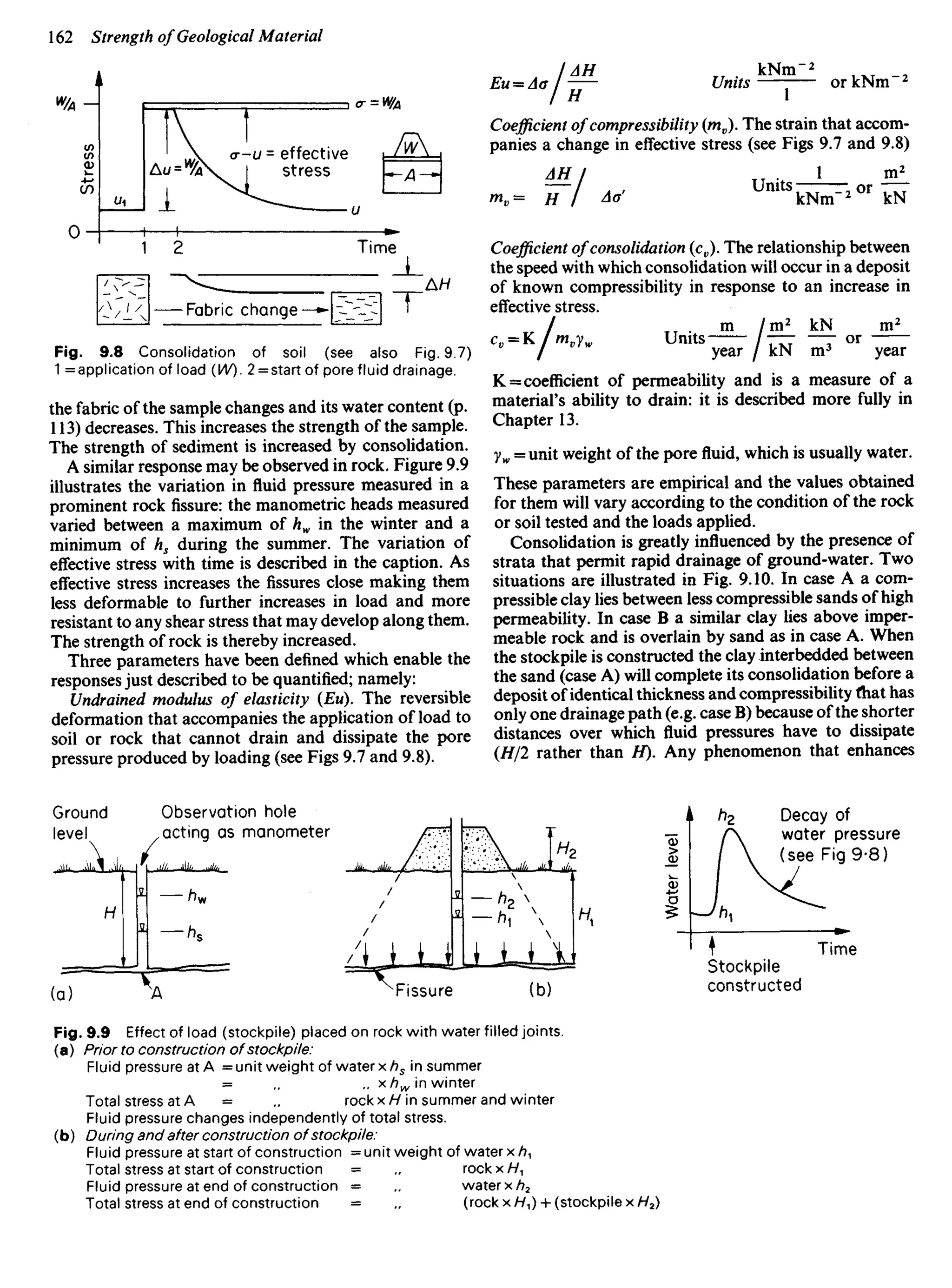

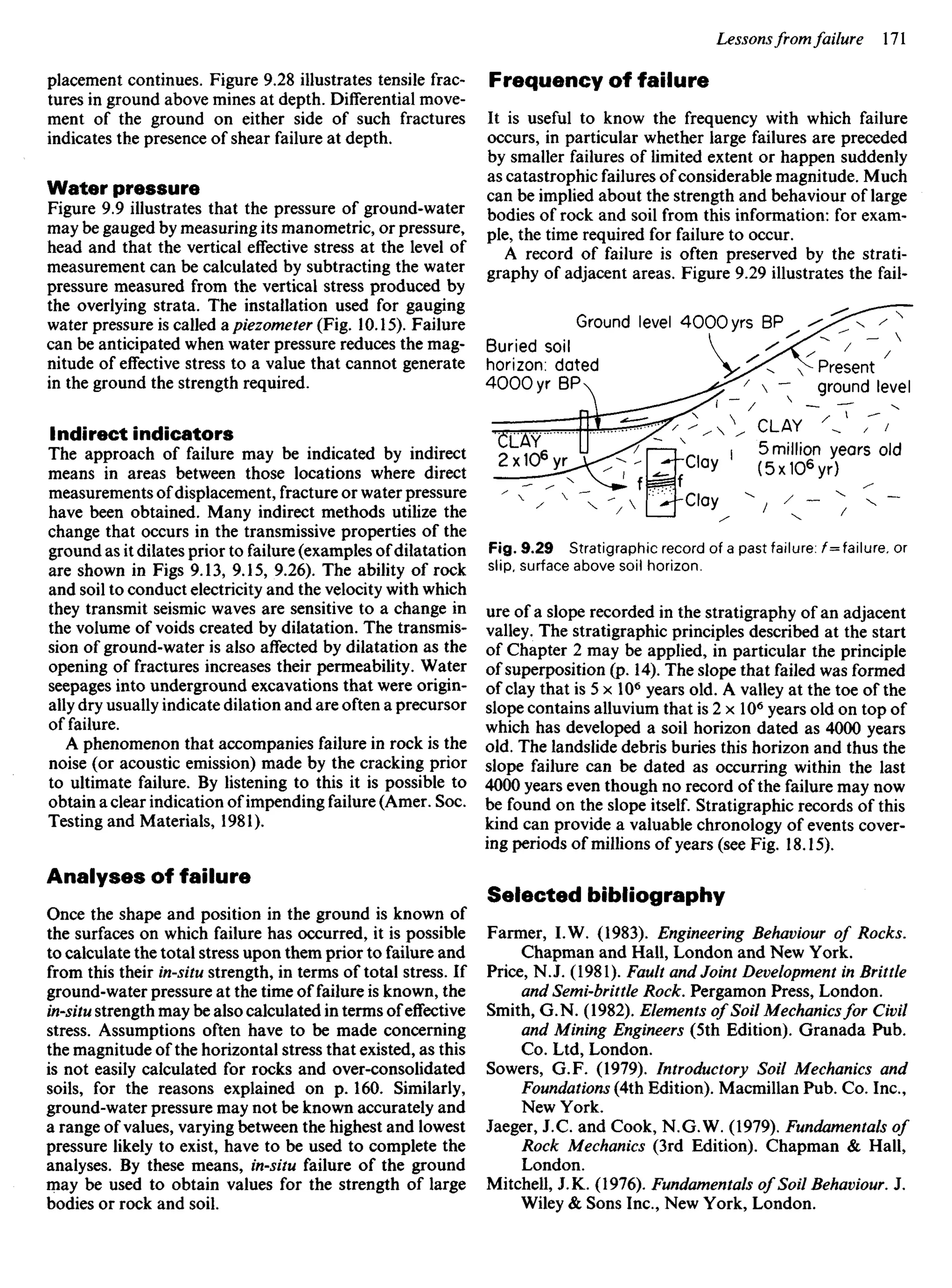

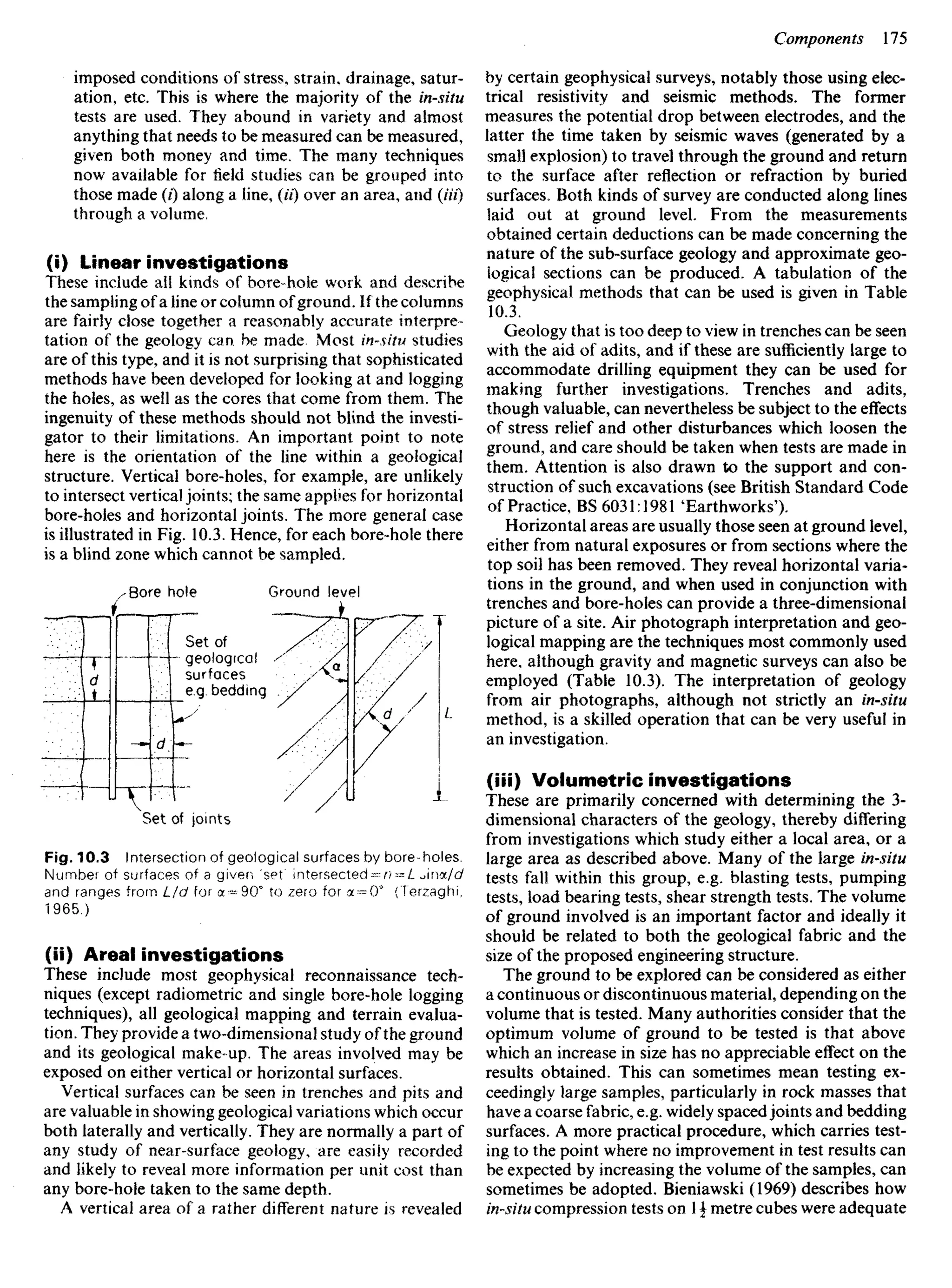

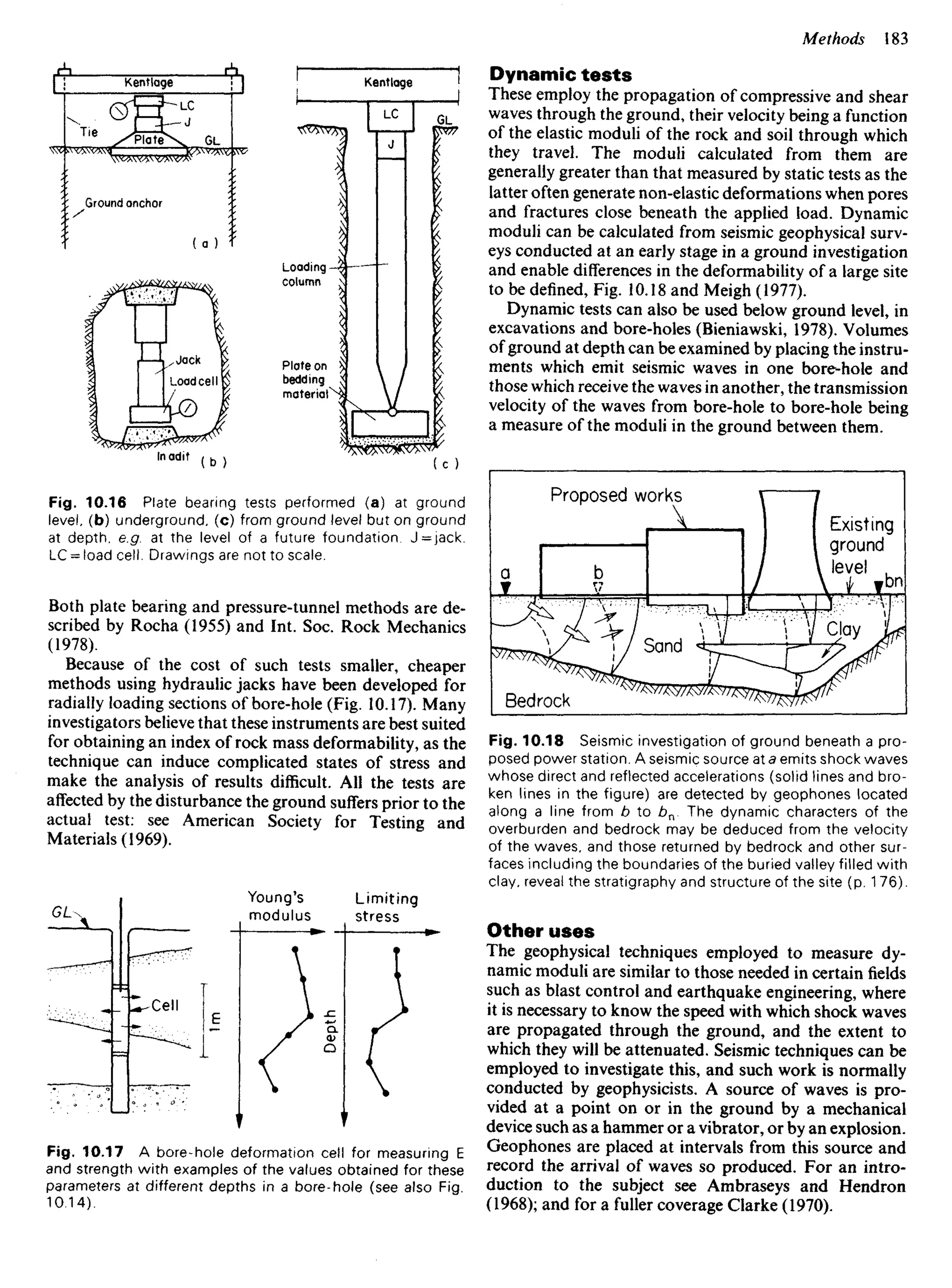

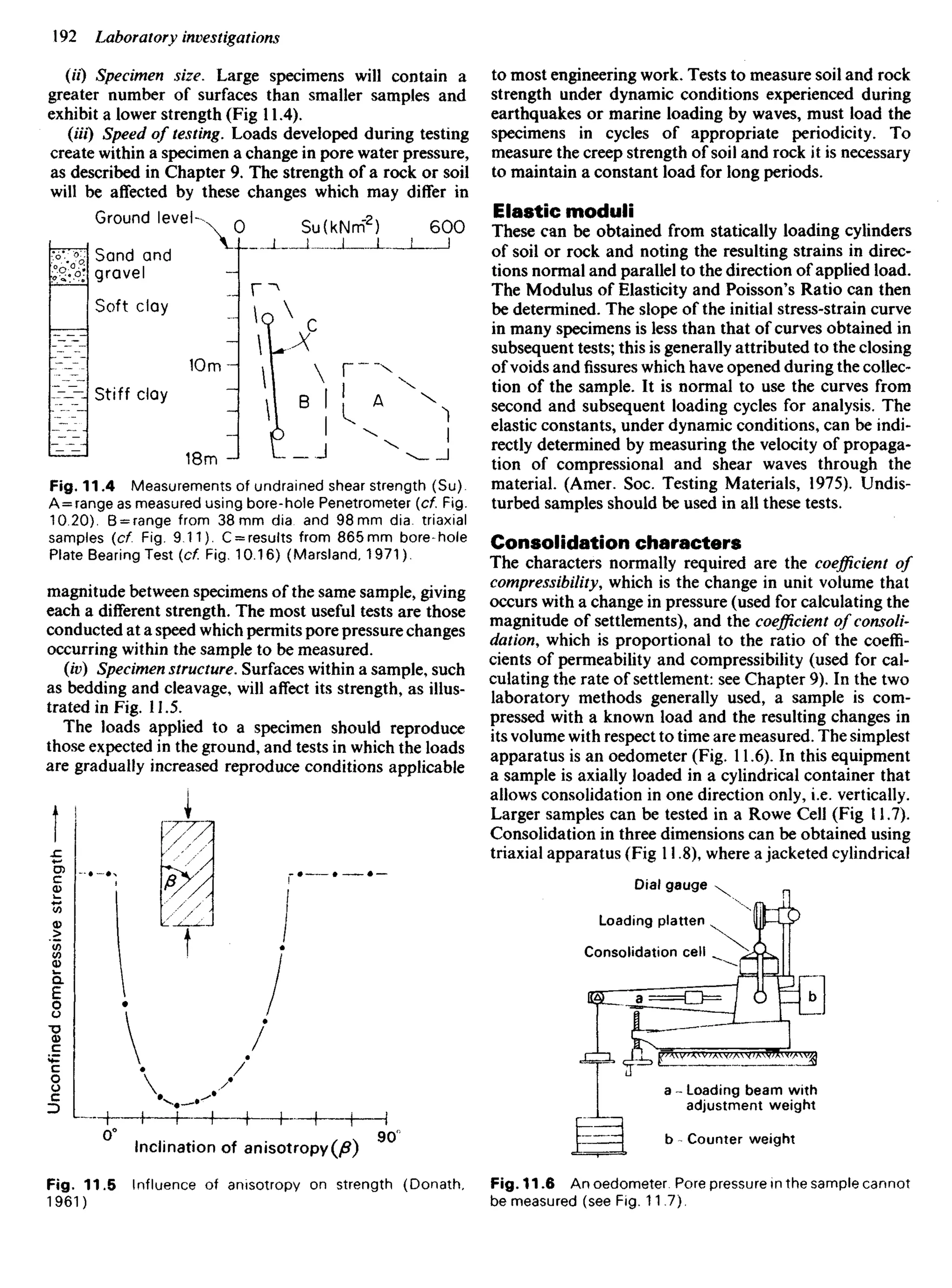

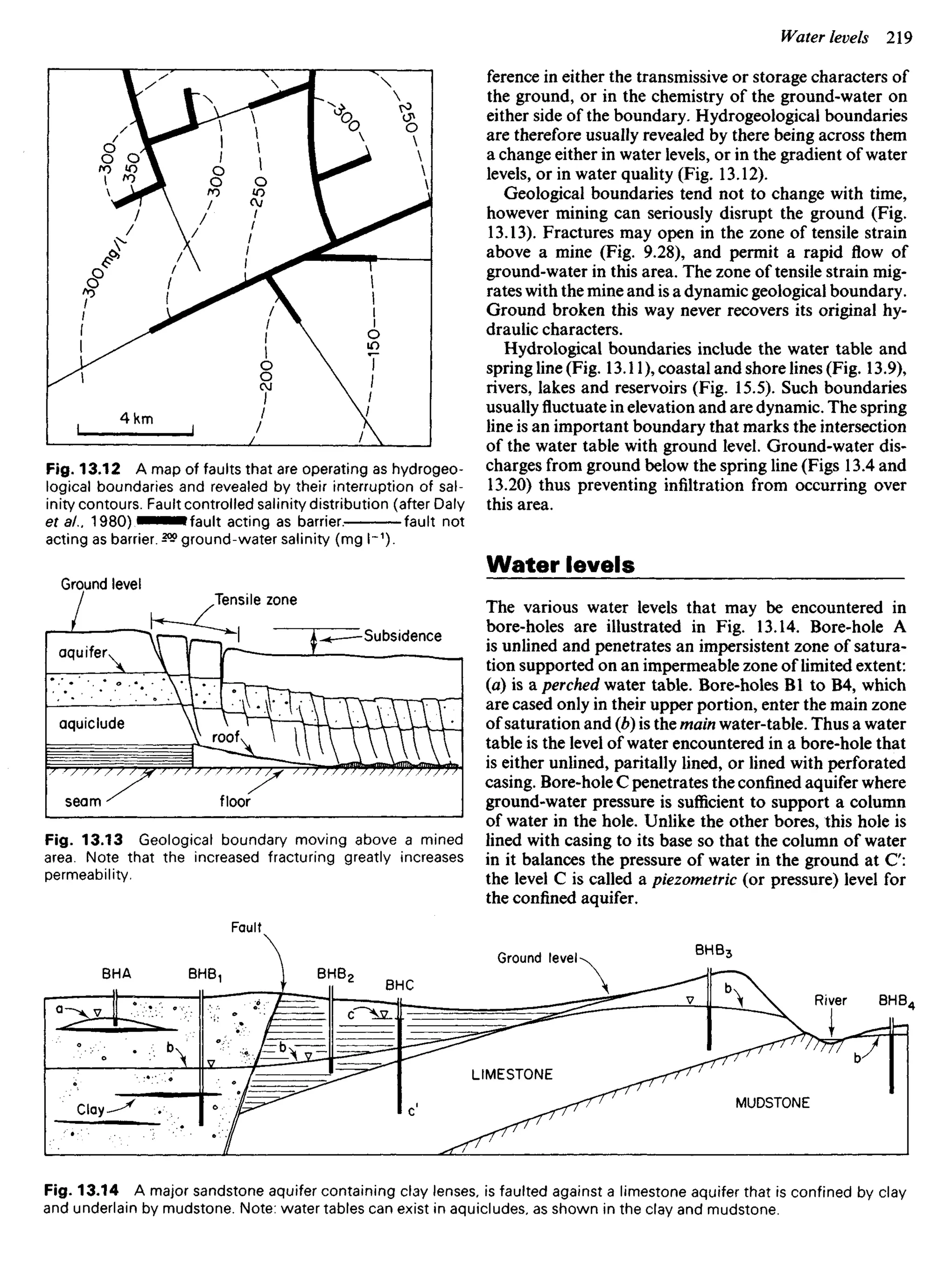

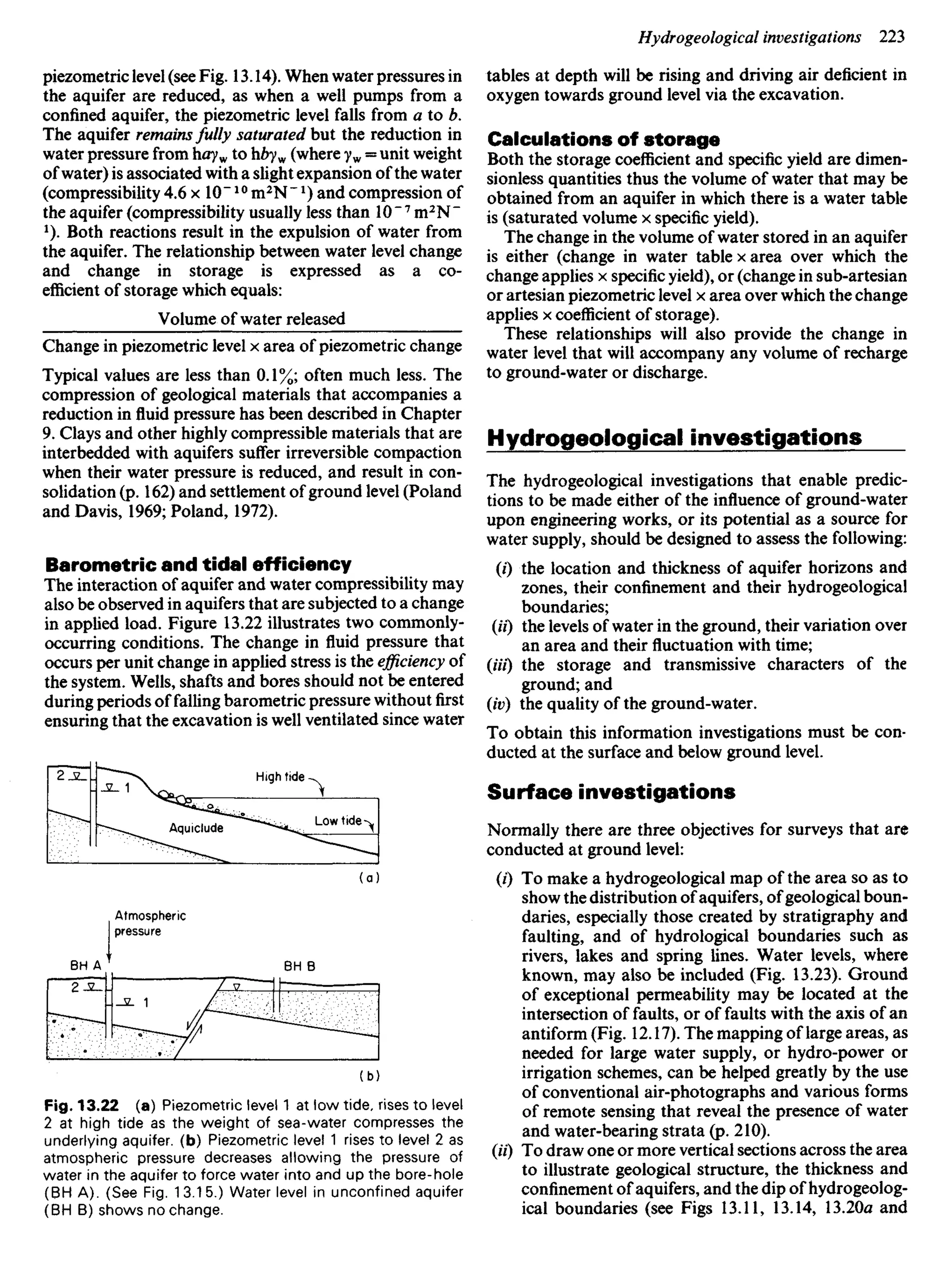

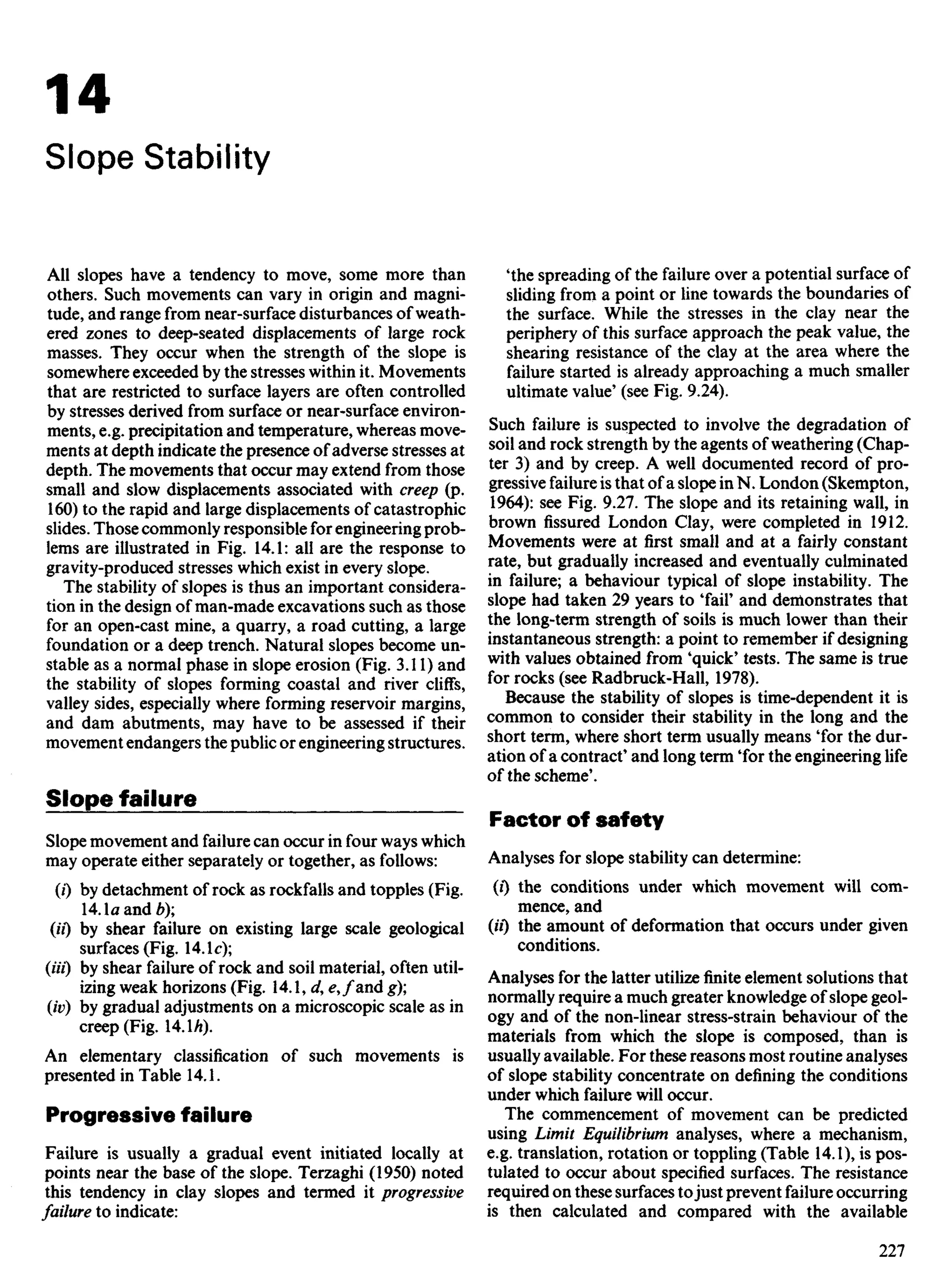

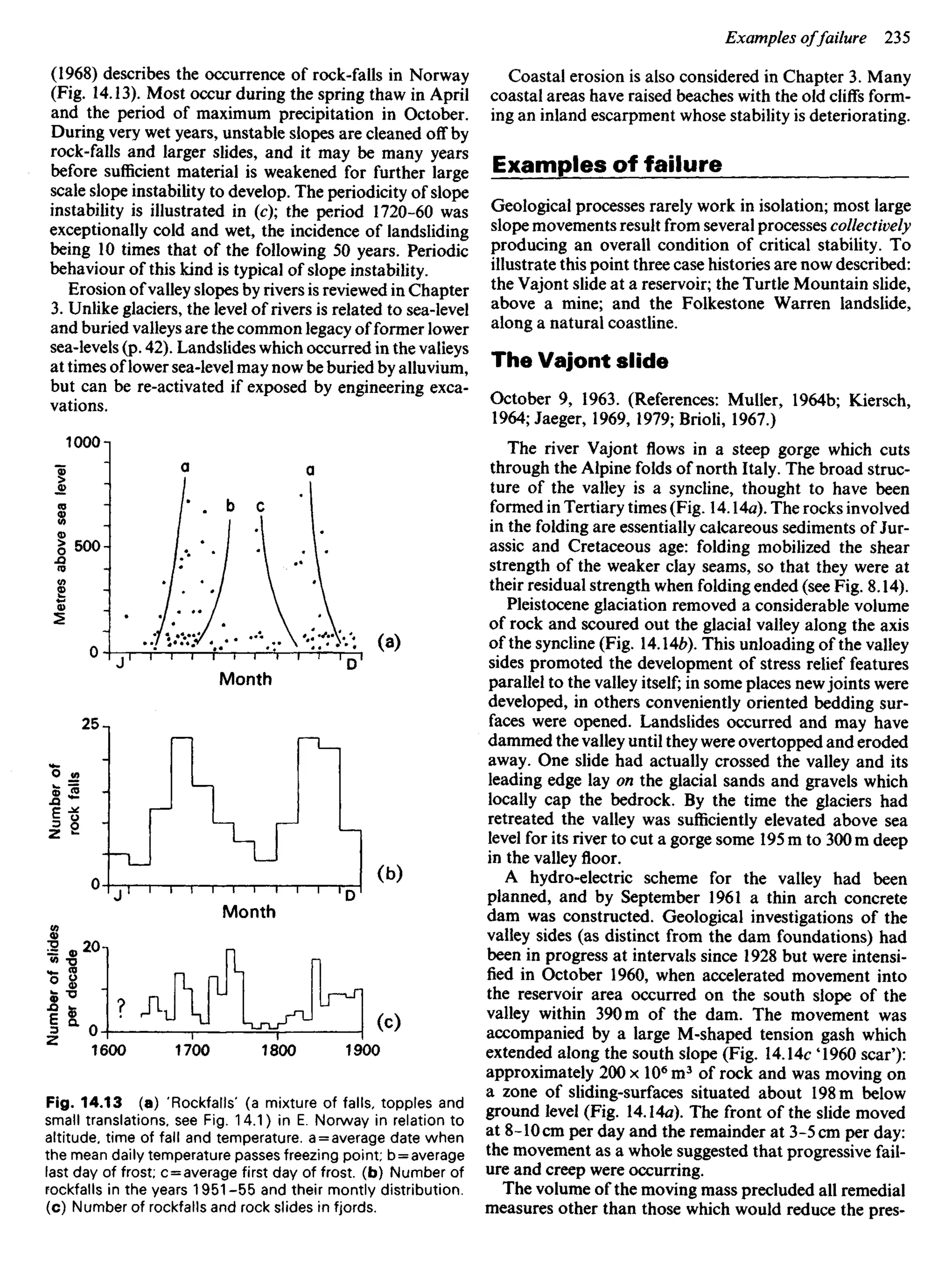

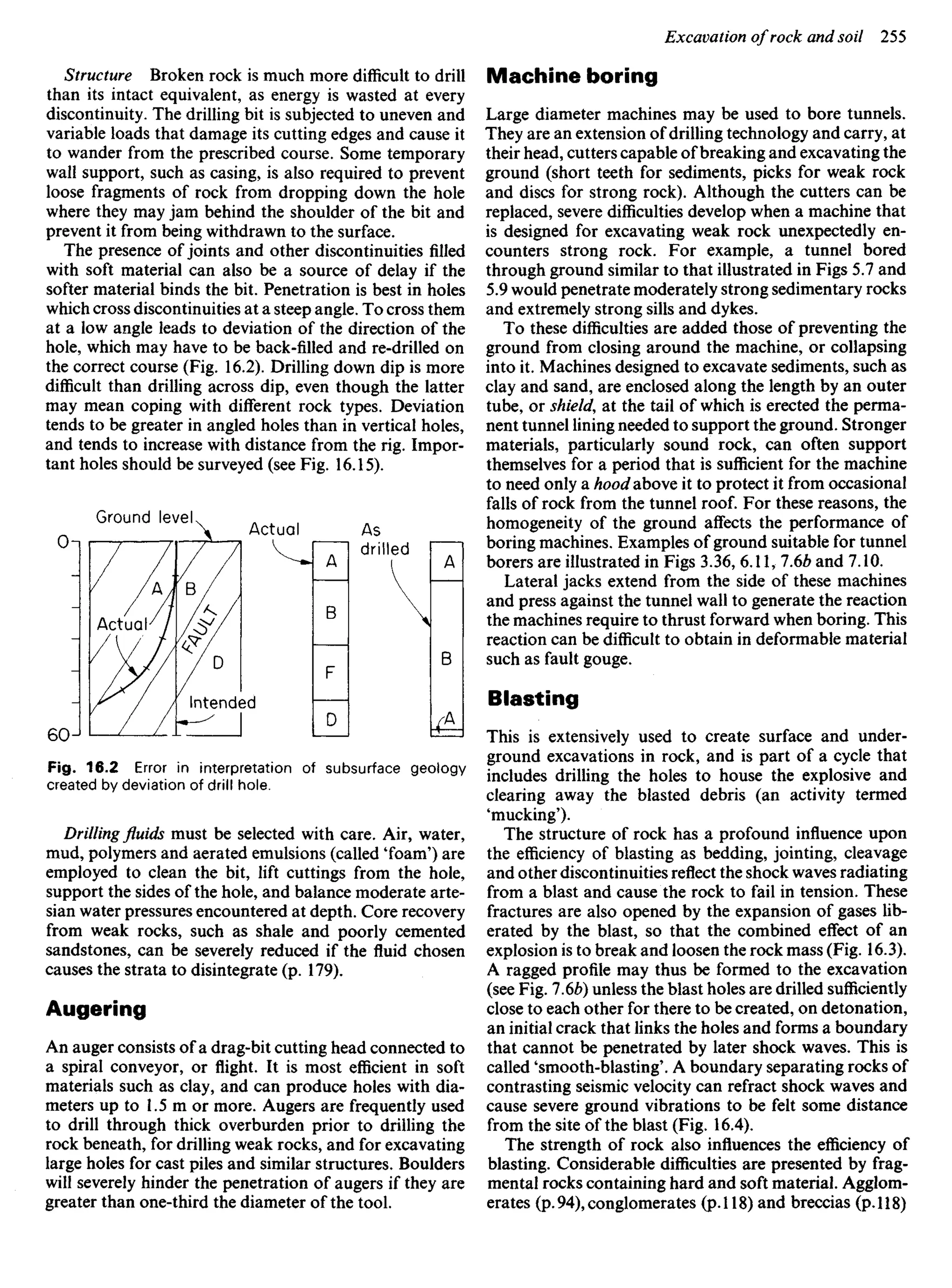

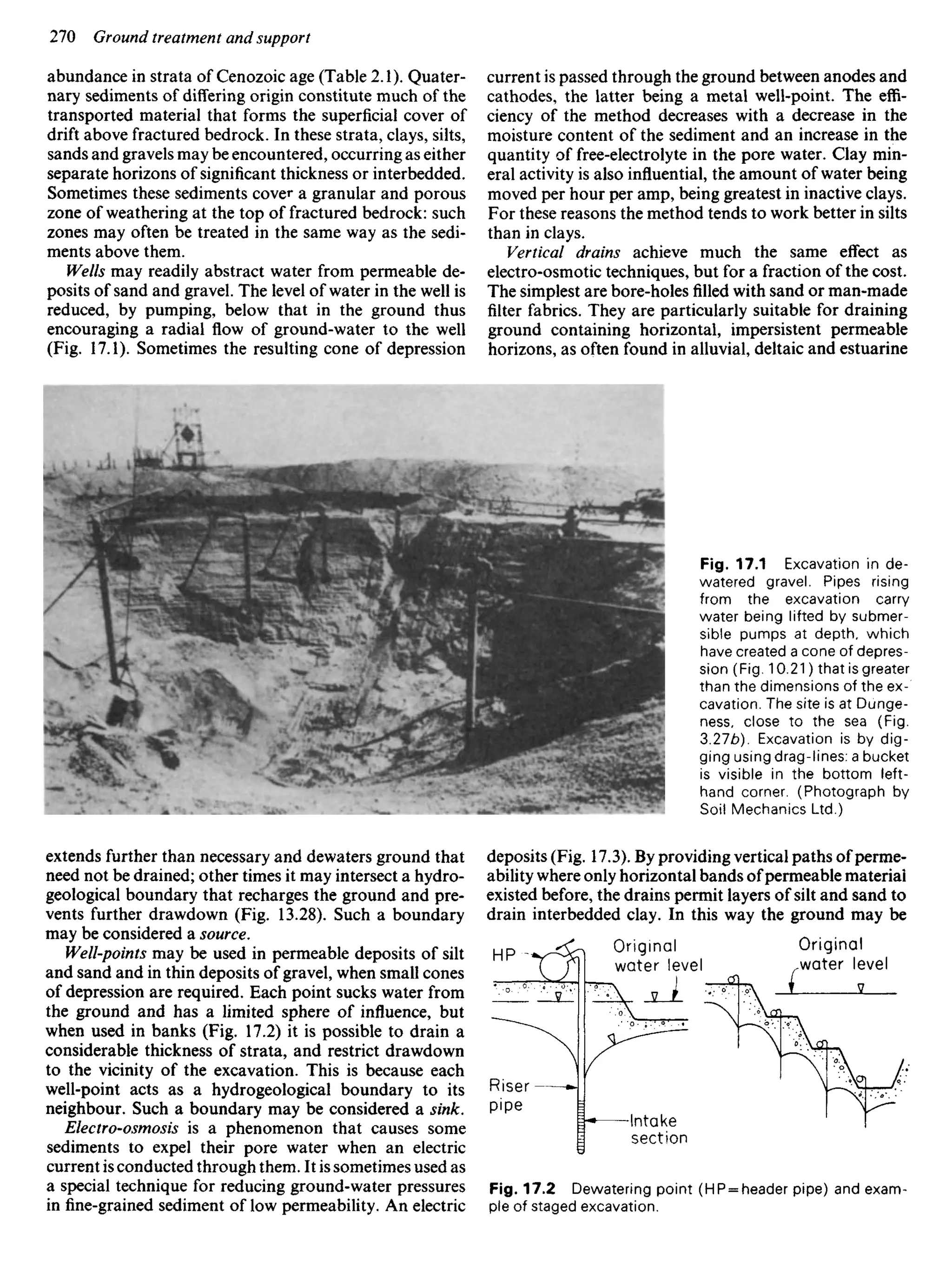

Figure 11.1 illustrates a 20 m deep bore-hole sunk to

investigate the ground beneath a foundation 10 m x 10 m

square. If samples are taken at 2 m intervals, as in the

figure, the volume sampled will be about 1/250 000th of

the ground subject to loading. This example demonstrates

the care required when selecting samples for testing.

Weak strata and zones of weakness in soil and rock

should always be tested. Specimens to be tested in a

laboratory normally have dimensions which prevent

them from containing major surfaces of weakness, such

as joints and fissures, and laboratory tests usually over-

estimate in-situ shear strength. Unavoidable deformation

of the specimen that occurs when it is being recovered

from the ground and prepared for testing, results in most

laboratory tests under-estimating in-situ moduli: (see

Marsland, 1975; and Lessons from Failure, p. 170).

Collection of samples

Changes in moisture content, either by wetting or

drying, can be avoided by sealing the sample with an

impermeable material such as paraffin wax or polythene

(see Stimpson et ai, 1970). This should be done as soon

as possible after the specimen has been collected; samples

should not be collected from areas where the natural

moisture content of the ground has been changed by

wetting or drying.

Loss of material is a hazard in sands, gravels, and

similar deposits which have little or no cohesion and

should be avoided. Comparatively undisturbed samples

of moist sand may be taken from natural exposures,

excavations, and borings, above the water table, by gently

forcing a sampling tube into the ground. Samples are less

easily obtained below the water table, and if they are to

be taken from a bore-hole, the water level in the hole

should be kept higher than that in the adjacent ground.

The flow of water outward from the bore-hole will then

tend to prevent the loss of finer particles which would

otherwise be flushed from its sides by inflow of water

from the surrounding ground. Having obtained a sample,

loss of material from it should be avoided during its

transport to the laboratory. These problems are less

severe when dealing with rocks than with weak materials

and drilling fines, which should be handled with special

care.

Local over-stressing often occurs with the trimming

and transport of soft materials such as soils. Disturbance

from trimming is affected by the sampling and cutting

tools that are used, and cutting edges should be sharp so

as to cut smoothly and cleanly. They should also be thin

so that they cause little displacement when passing

through the soil. This is important in the design of tubes

that are pushed into the ground to collect a sample; an

area ratio of the form

Da2

- Db2

I

[-5ST-] xI00%

should be observed, where Da is the outside diameter of

the cutting edge, and Db its inside diameter. The above

represents the area of ground displaced by the sampler in

proportion to the area of sample. Severe disturbance is

likely to occur on the margins of a sample if the ratio is

greater than 25%, as illustrated in Fig. 11.2.

Disturbance can also occur during the extrusion of

samples either from sample tubes or core barrels, and

care should be taken that the friction between the sample

and sampler wall is kept as low as possible, and that

excessive pressure is avoided during extrusion. Harder

materials such as rocks can be sampled by coring, as

described in Chapter 9. Hand specimens of rocks should

be at least (8 cm)3

to (10 cm.)3

and representative of the

Future foundation Ground !eve!

Borehole with

100mm dia x

200 mm samples

every 2 m

Stressed ground

Fig. 11,1 Some limitations with sampling. The total volume

of samples is approximately 1/250000th of the stressed

ground. See also Fig. 10.1.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ageologyforengineersseventhedition-240123054612-a0c16209/75/A_Geology_for_Engineers_Seventh_Edition-pdf-172-2048.jpg)

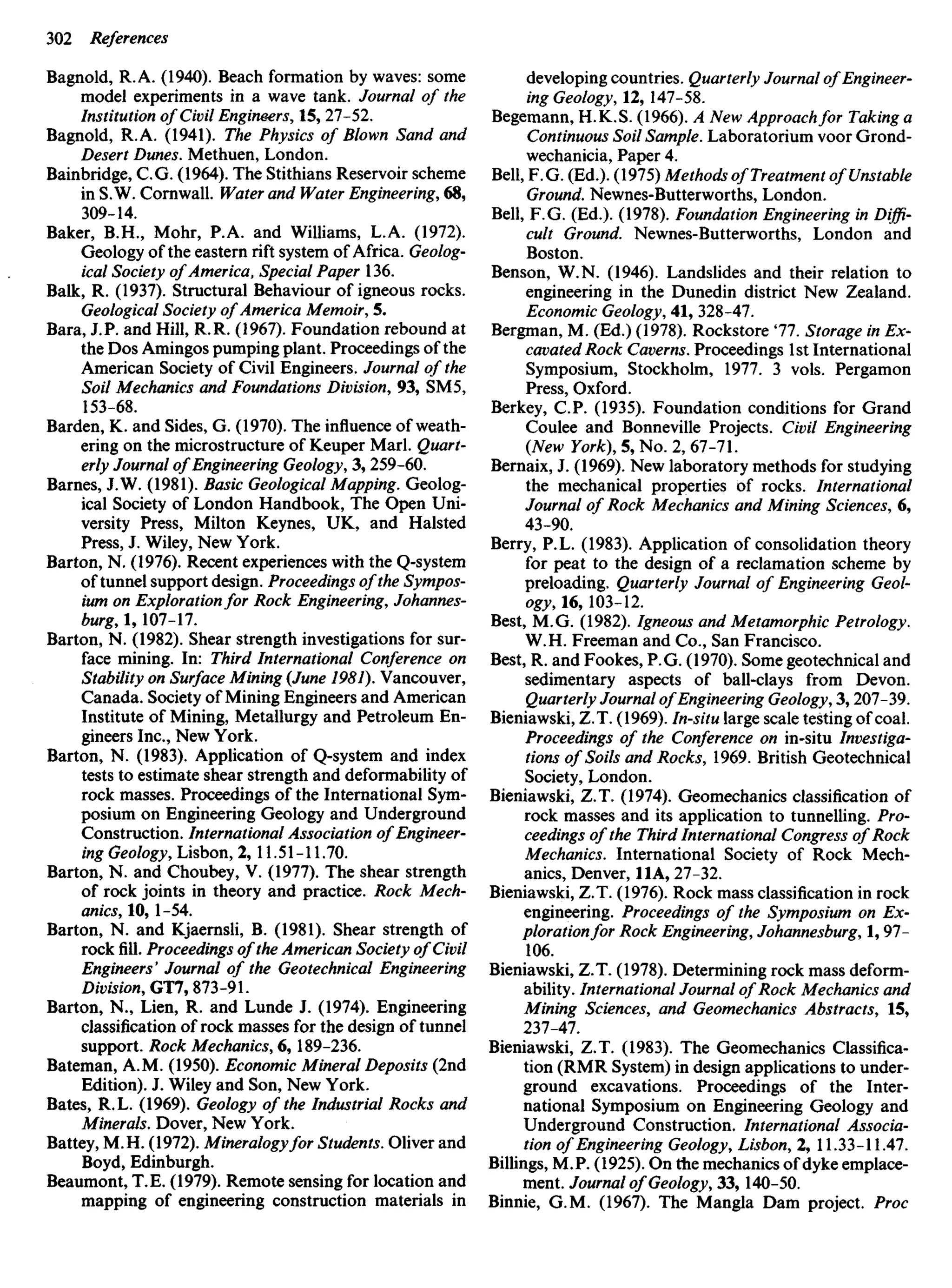

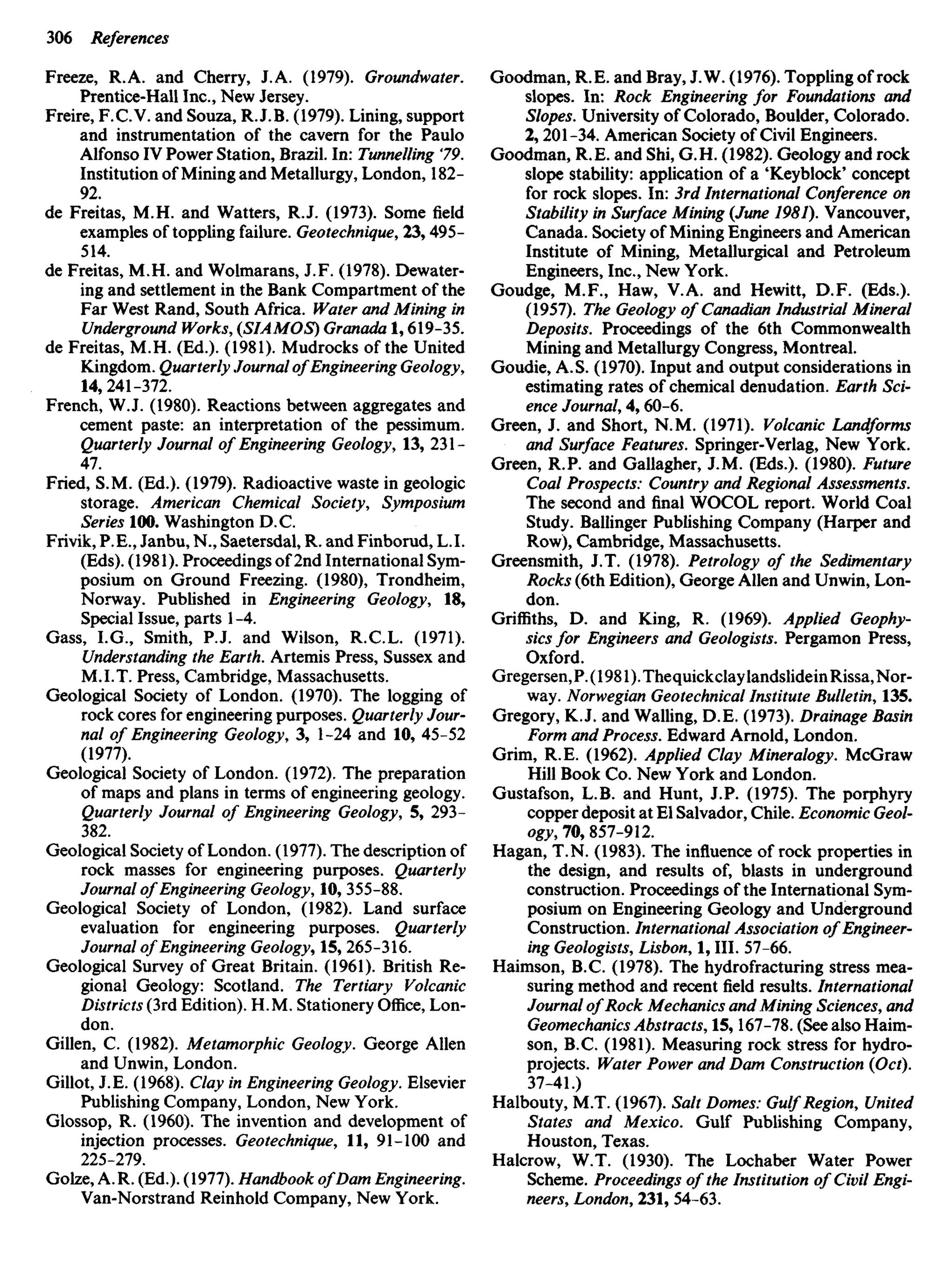

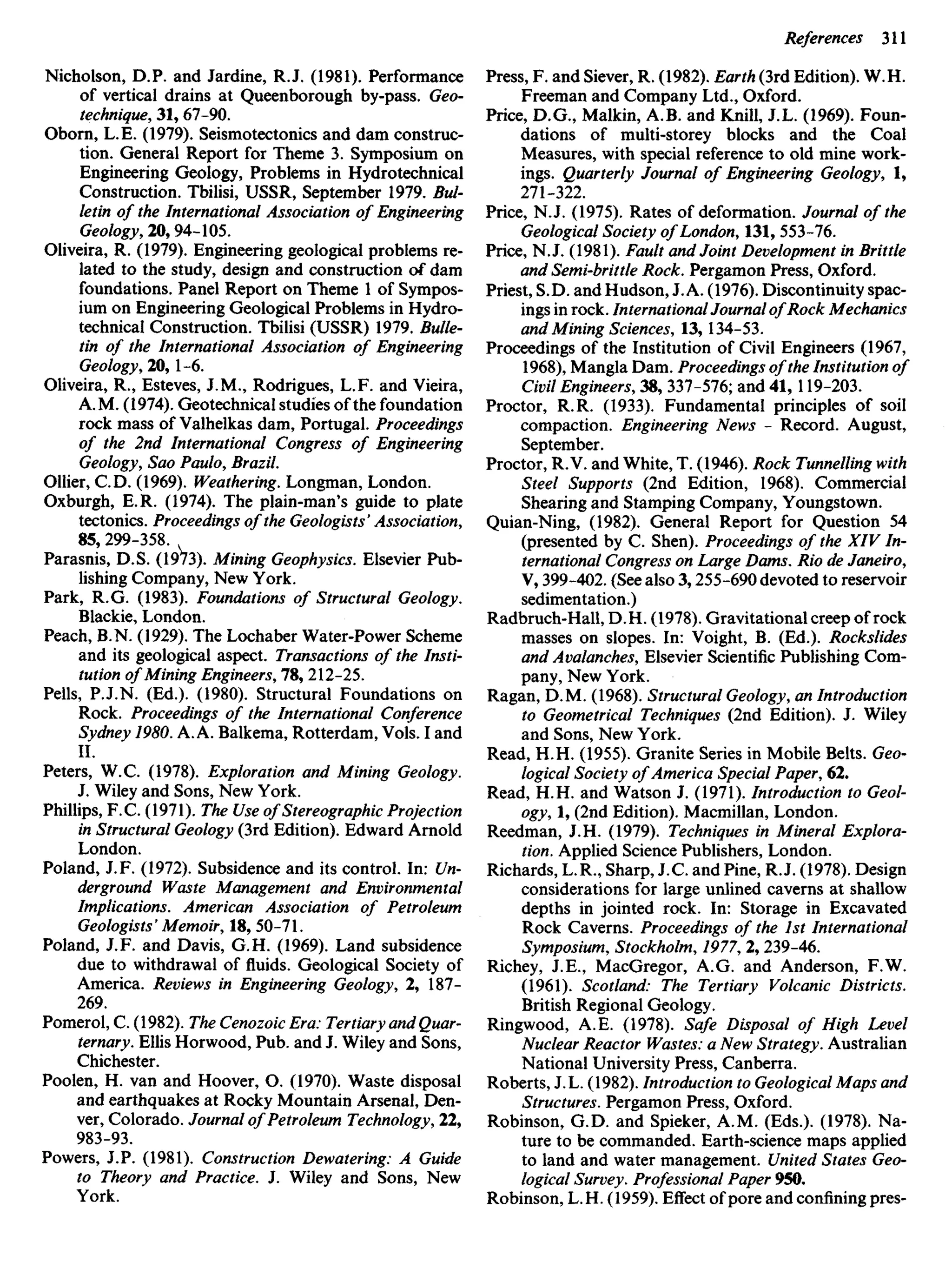

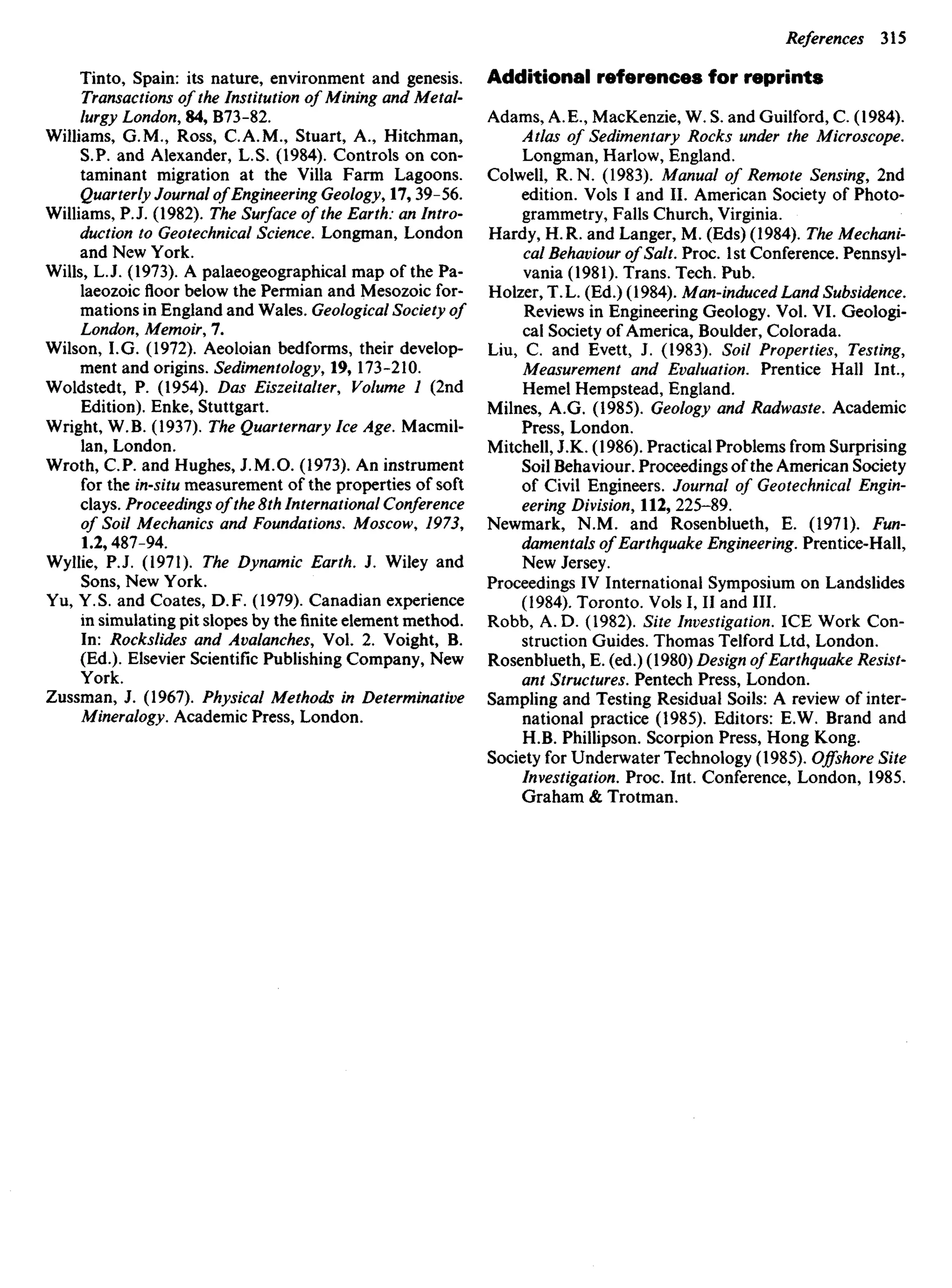

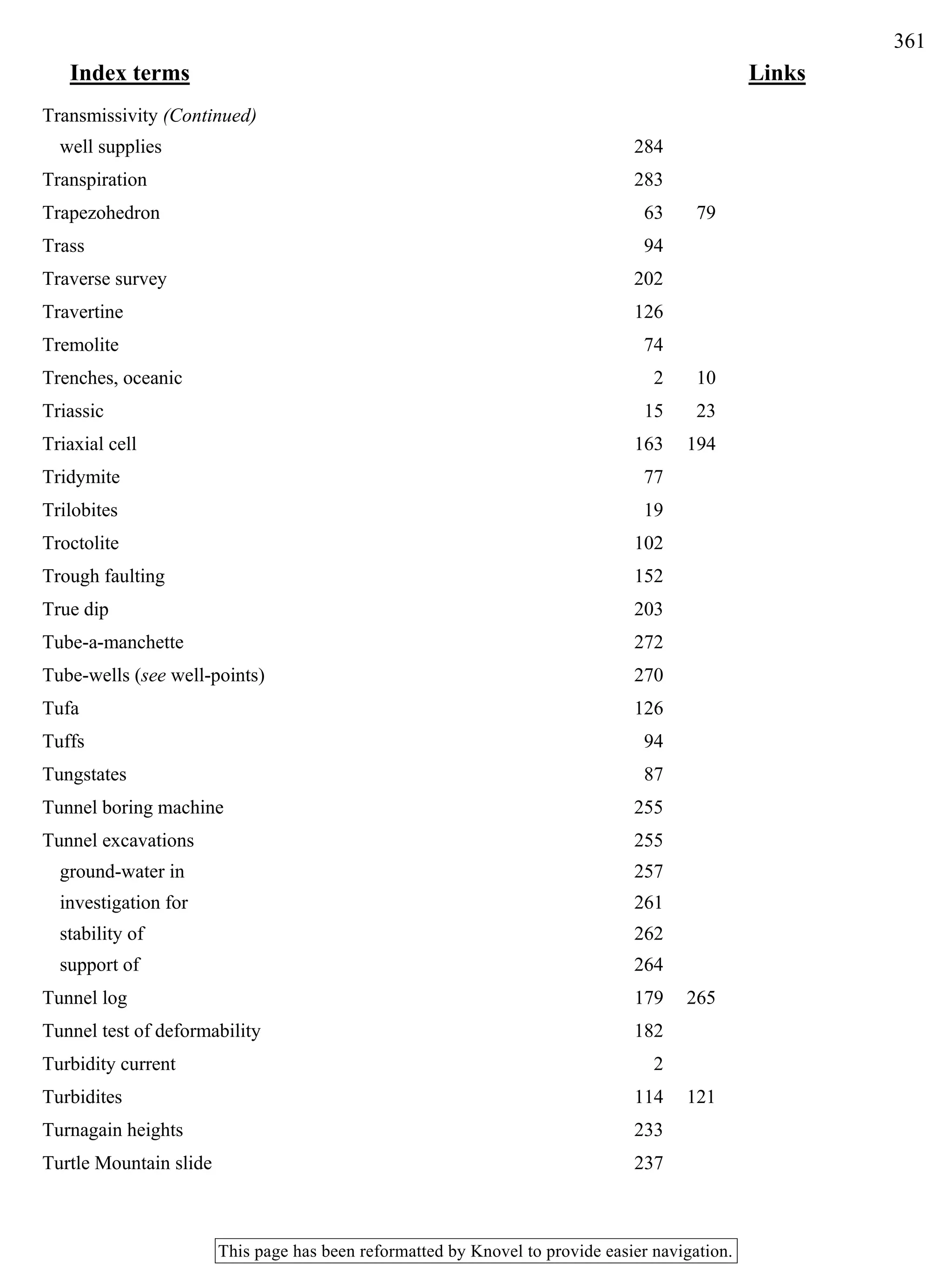

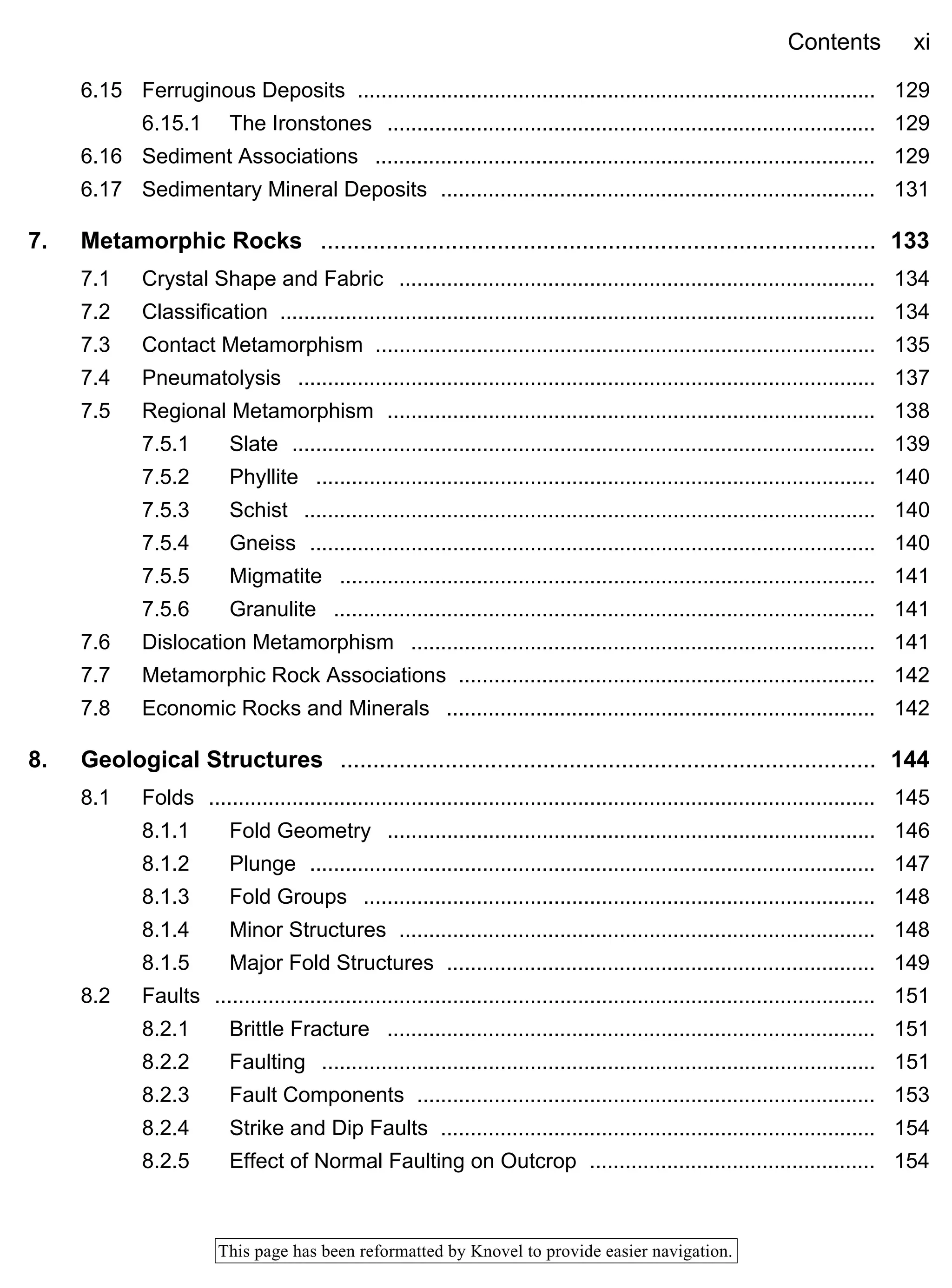

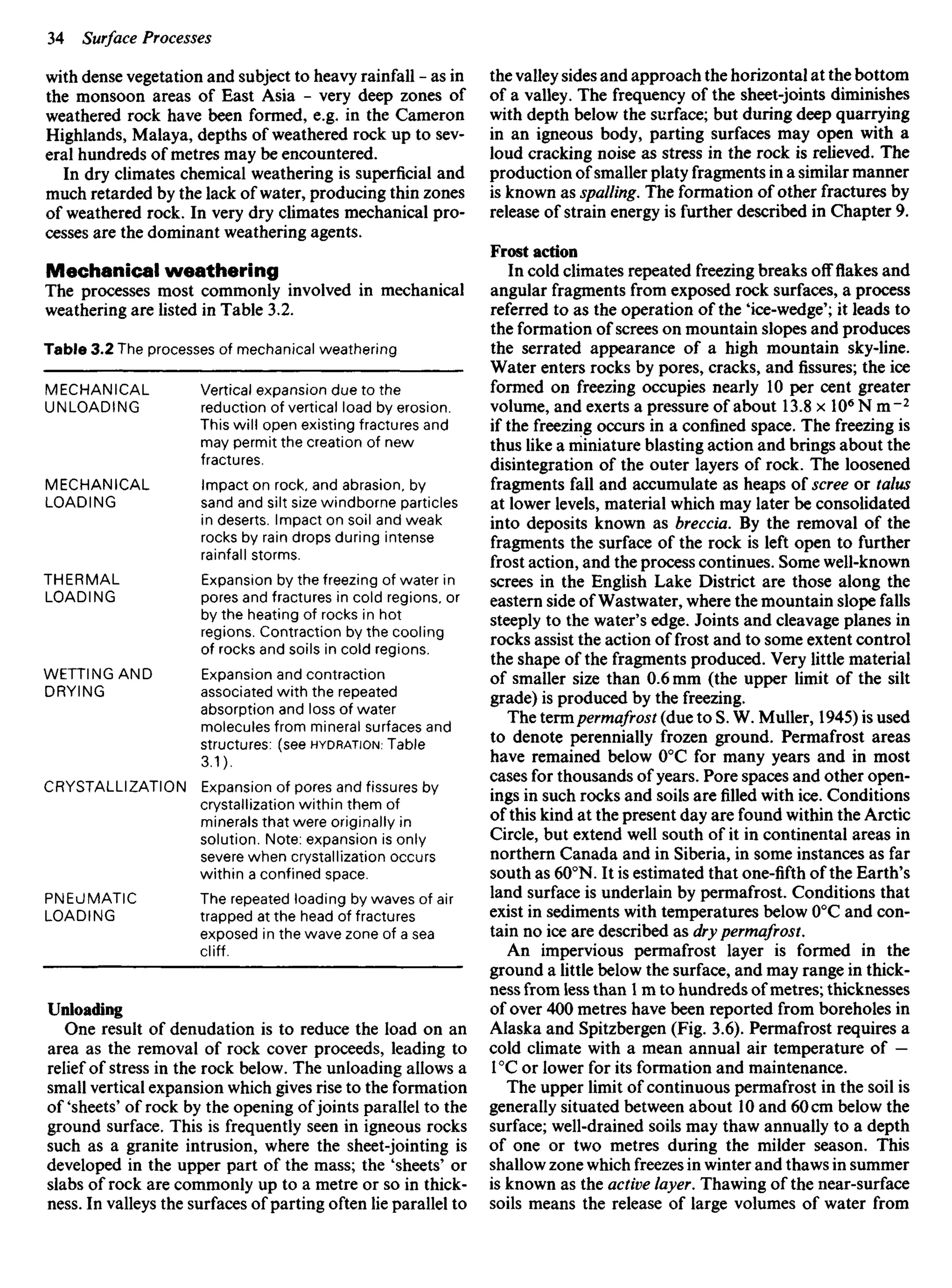

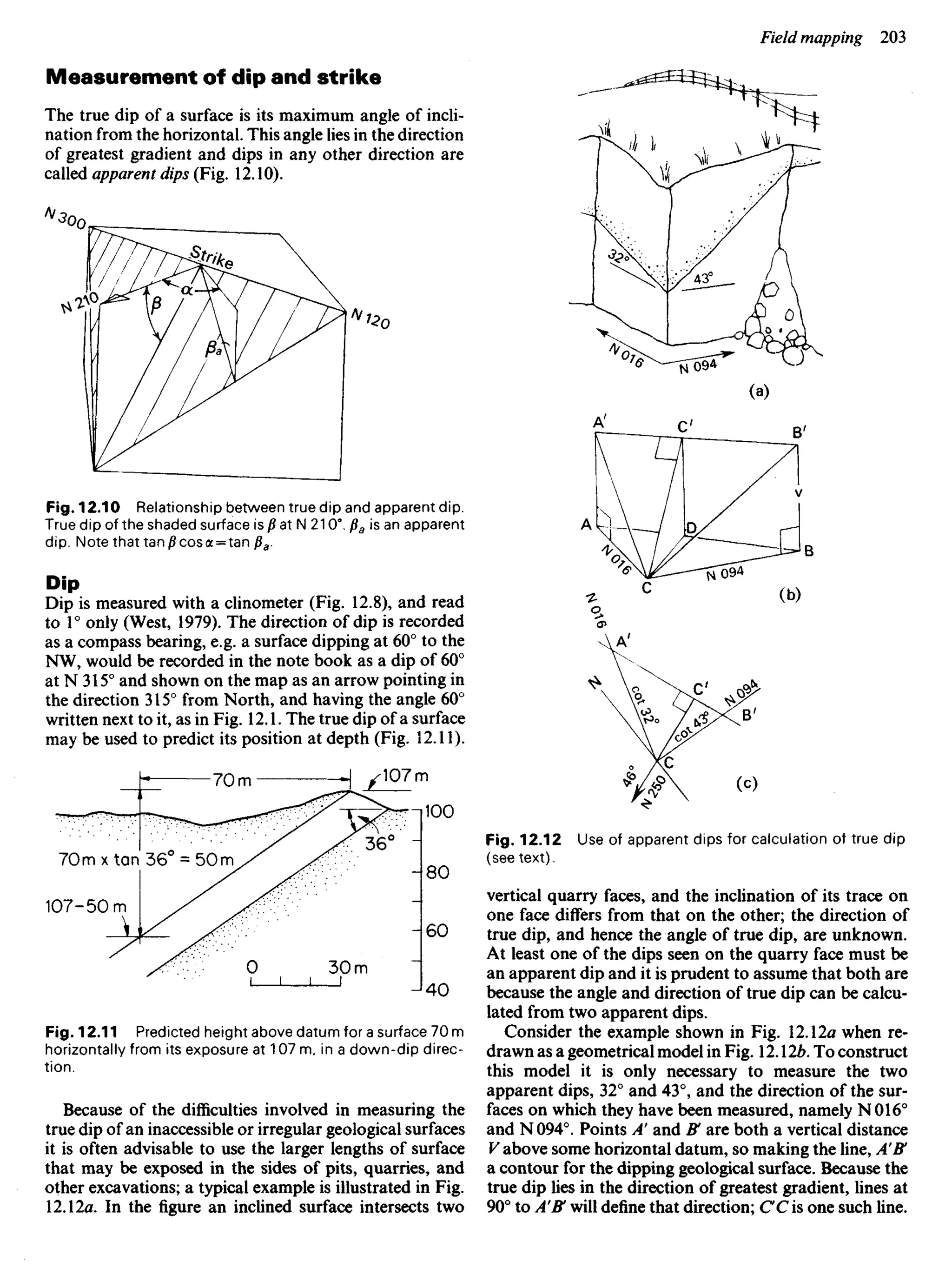

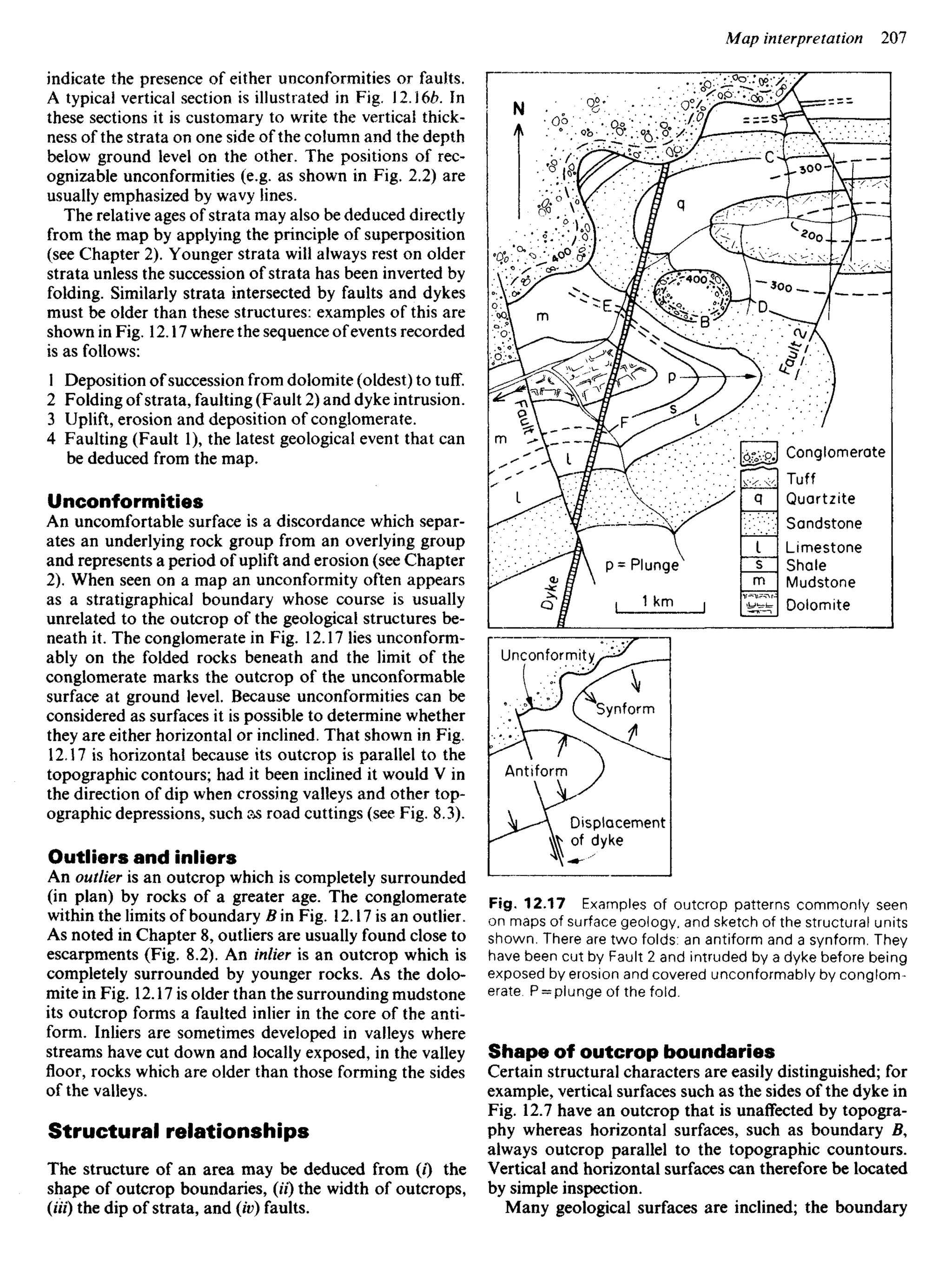

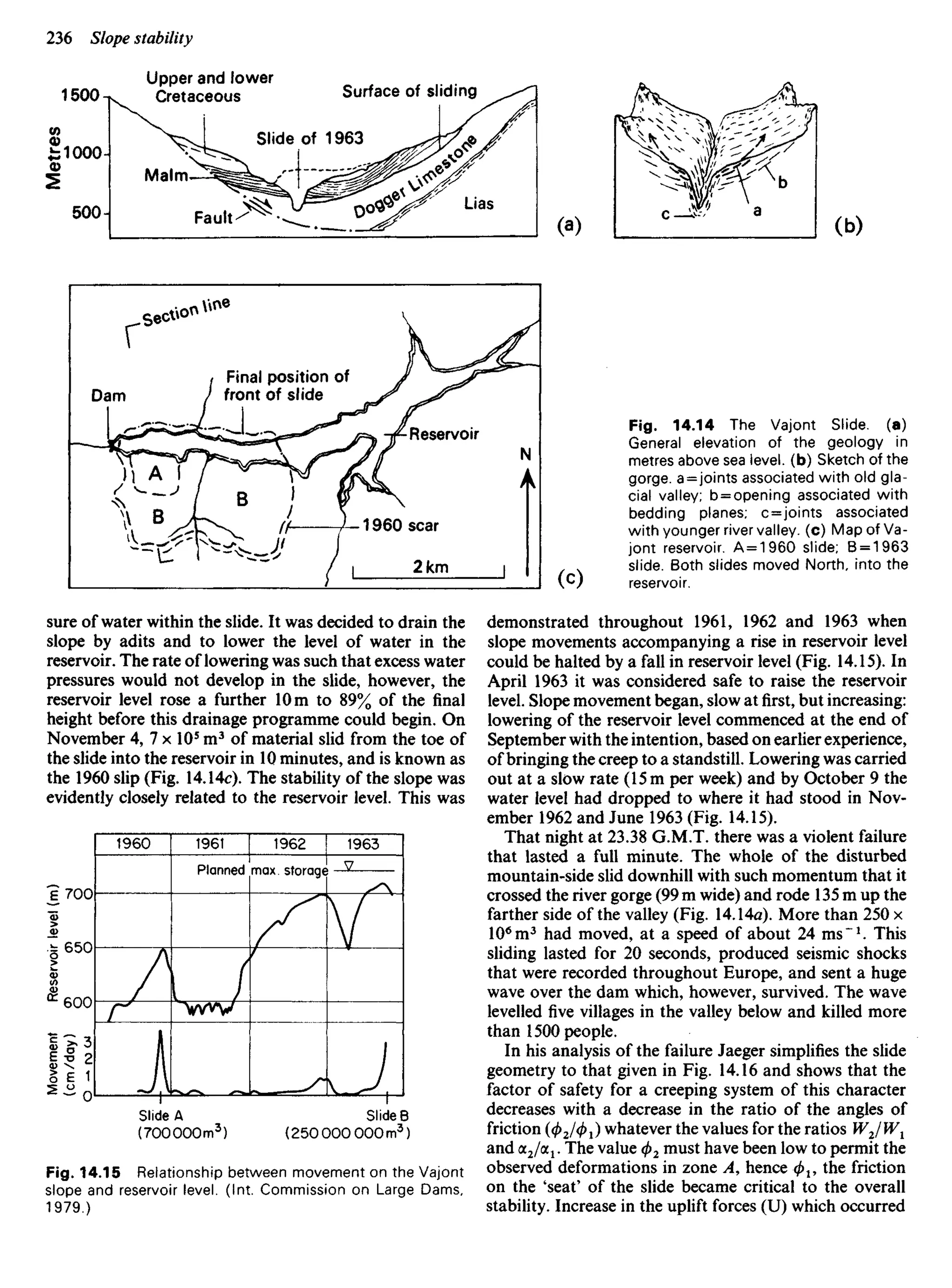

![The true dip, or inclination of CC to the horizontal, is

conveniently found by making a two-dimensional plan,

Fig. 12.12c. This diagram can be drawn directly from

field data using the following steps:

1 Draw a line to represent the direction of magnetic

North.

2 Select a point on this line to represent C.

3 From C draw two lines CA' and CE so that they are

correctly oriented to North. It is then necessary to

locate the points A and E on these lines.

[One of the commonest mistakes made with this construc-

tion is to draw the lines A'C and B'C on the wrong side of

the N-S line. The direction of faces A and B in Fig. 12.12a

could equally well have been recorded in the field as

N 196° and N 274° respectively. These directions, plotted

directly in plan, would have put the triangle AEC (to be

constructed) on the west side of the N-S line. The angle

of dip calculated would be the same as before, but the

direction of dip, if measured in the C-C direction, would

be in error by 180°. The construction triangle should

point in the same direction as the field exposure.]

4 From Fig. 12.126 it can be seen that AC=AAcOt 32°,

and BC=BE cot 43°. Because AA = BE= V, the ac-

tual length of V is immaterial to the construction and

can be conveniently taken as unity. The point A is

located a distance equal to cot 32° from C along the

line CA, and the point E a distance equal to cot 43°

along the line Ci?', to some suitable scale.

5 A line drawn at 90° to AE, i.e. CC, will lie in the

direction of true dip, and this direction can be

measured directly from the plan, i.e. N 250° in this

example.

The angle of true dip is C CD in Fig. 12.126. The length

DC = DC x cot CCD, because DC = V= 1, the equation

reduces to DC=cot CCD. Fig. 12.12c. Hence the angle

of true dip is that angle whose cotangent is equal to the

length CC, i.e. 46° in this example.

This graphical method is usually referred to as the

cotangent construction, and it can be used to interpret

the inclined surfaces exposed in trial pits, tenches, adits,

and similar excavations. Other methods are described by

Phillips (1971).

Strike

The strike of a surface is the direction of a horizontal line

drawn at 90° to the direction of true dip. The direction

N 120° (or N 300°) is the strike of the surface shown in

Fig. 12.10 as is the direction of the line AE in Fig. 12.126.

Because of its horizontality a line drawn in the direction

of strike is equivalent to an elevation contour for the

surface. Figure 12.13 illustrates how the strike directions

of a planar surface can be extended to produce strike lines

which are also contours for the surface and are called

structural contours. However, the majority of geological

surfaces are not planar and the unlimited extension of

strike lines away from the points at which dip and strike

are measured can result in incorrect predictions.

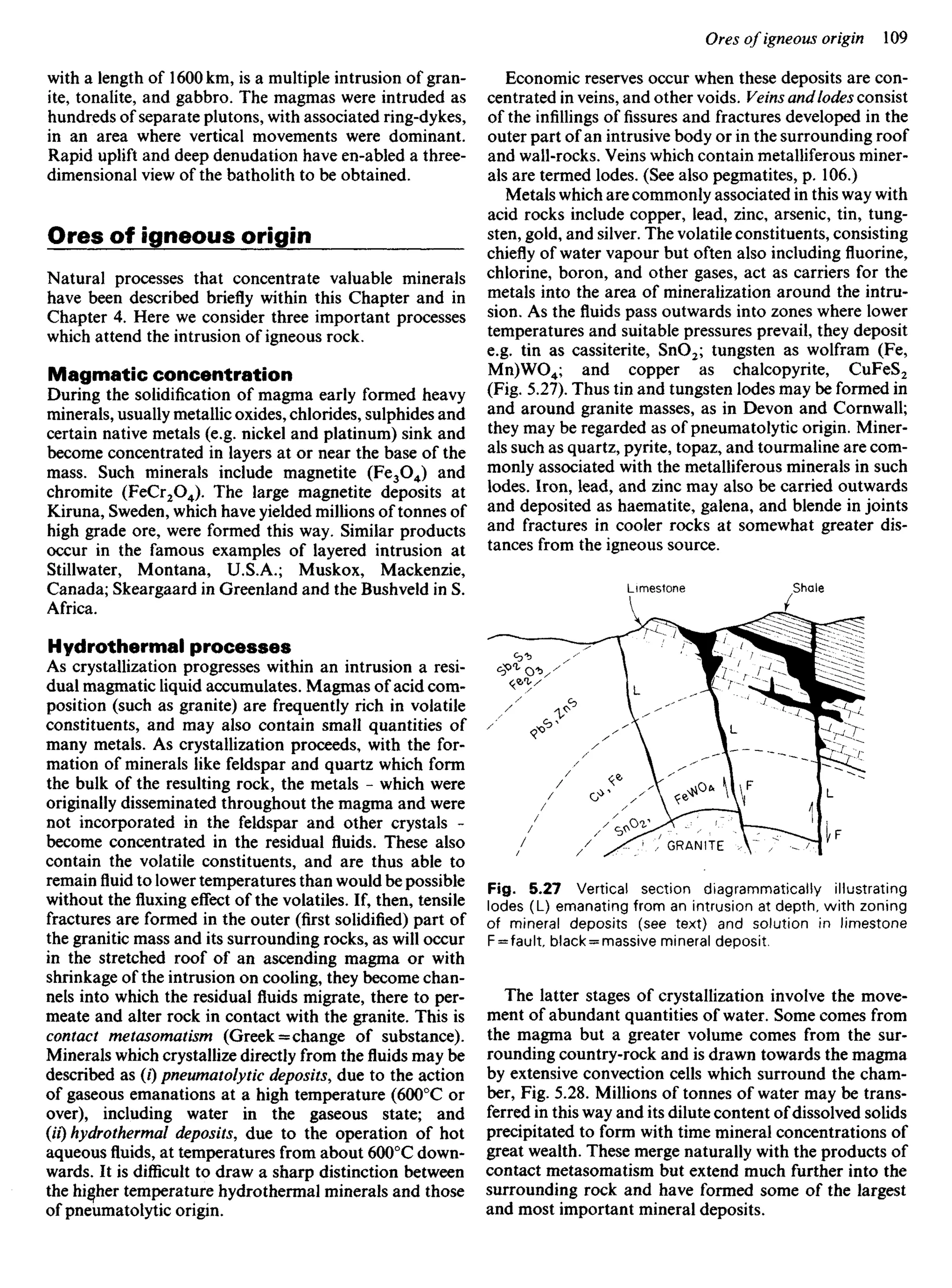

Fig. 12.13 Coastal exposure illustrating that strike lines at

chosen elevations can be extended to produce structural con-

tours for a surface.

Constructions for dipping strata

The two constructions described here may be used to

predict the likely position of a concealed boundary.

Construction from outcrop

Figure 12.14 illustrates two small valleys between which

a hillside exposure reveals thejunction of sandstone (dot-

ted) with underlying shales. The dip of thisjunction at the

exposure is 40° at N 160°. In order to predict the approxi-

mate position of the junction in the area around the

exposure the following construction is used.

Fig. 12.14 Location of concealed boundary as defined

using stratum contours (see text).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ageologyforengineersseventhedition-240123054612-a0c16209/75/A_Geology_for_Engineers_Seventh_Edition-pdf-188-2048.jpg)

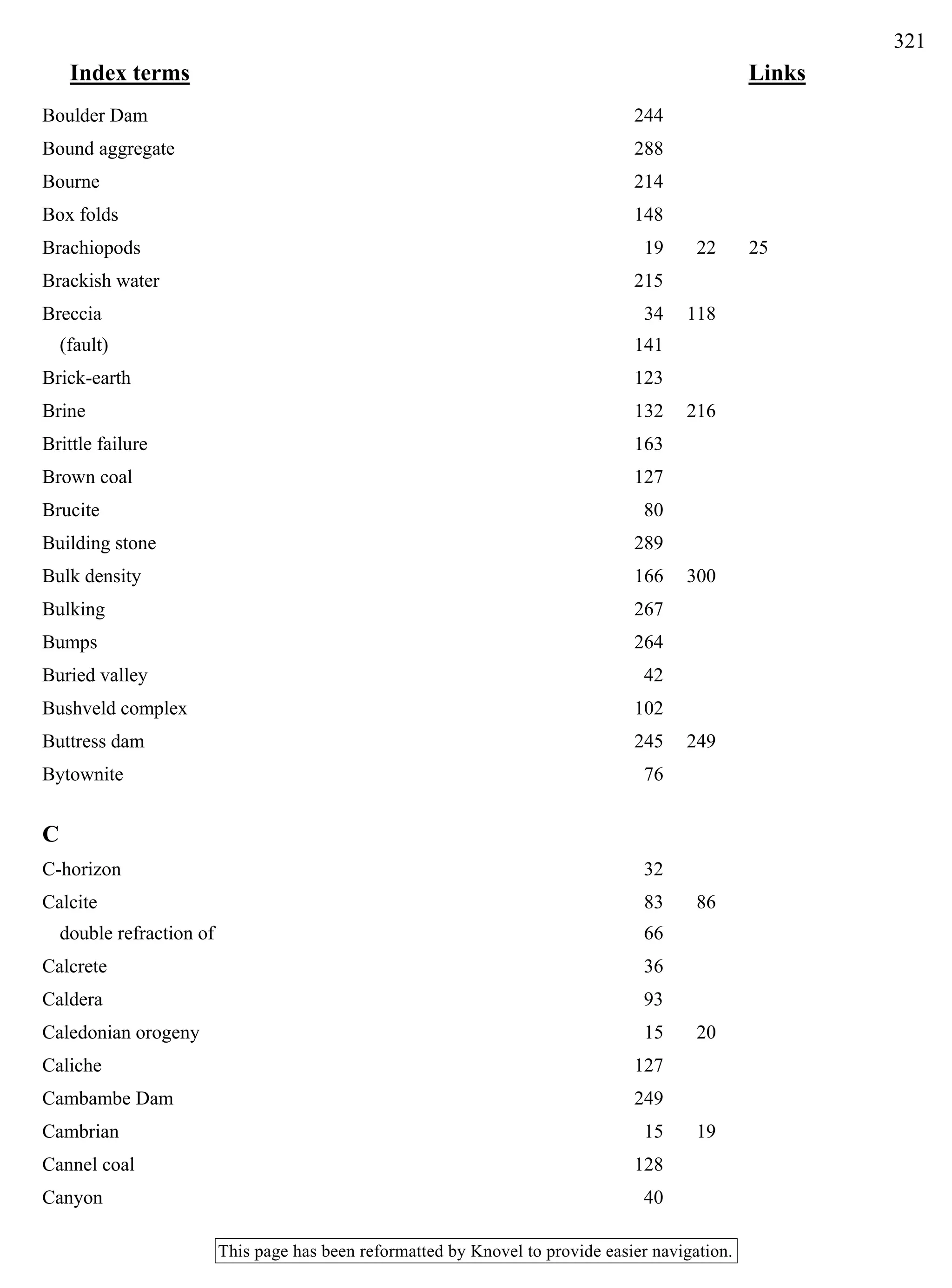

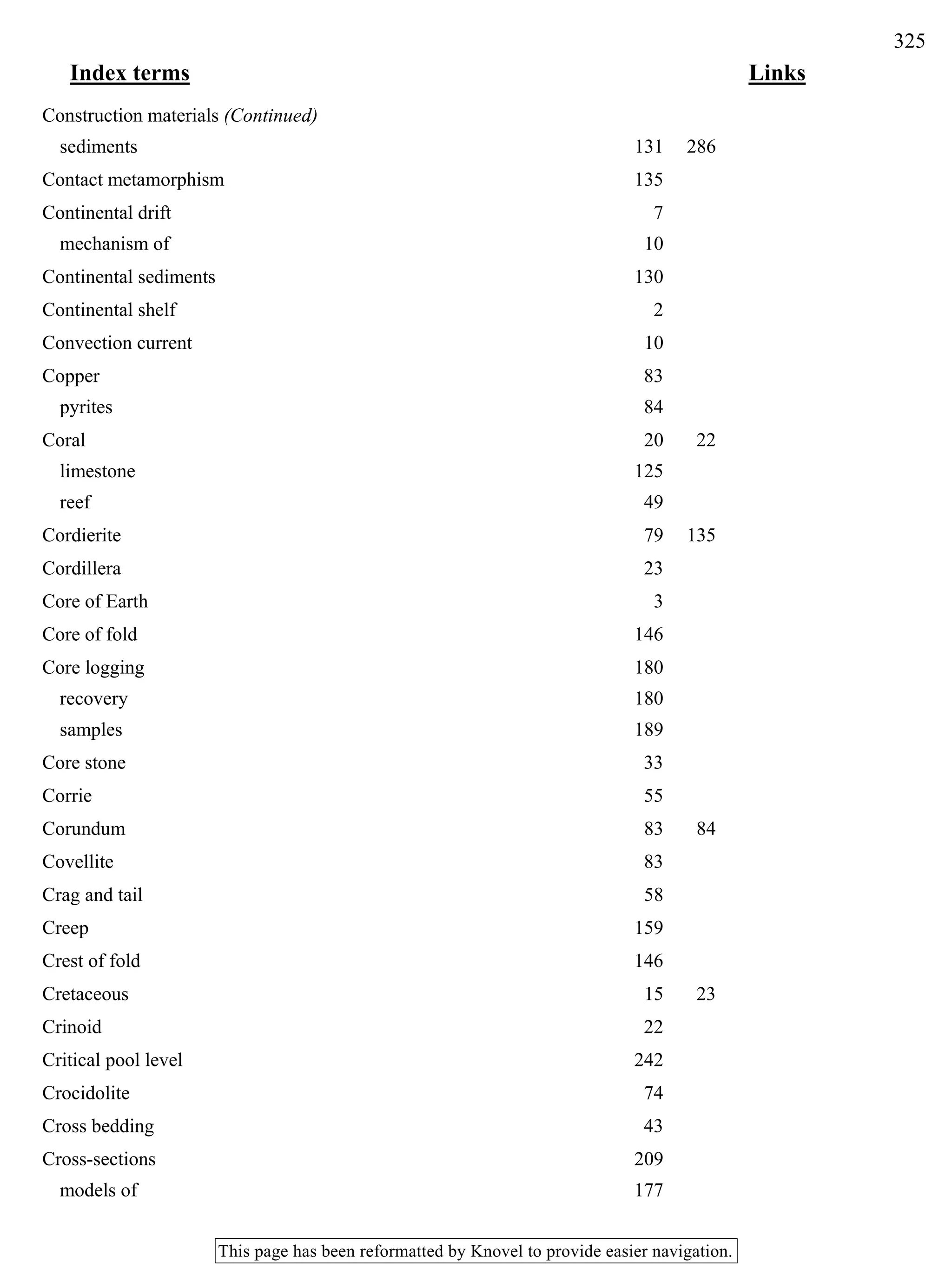

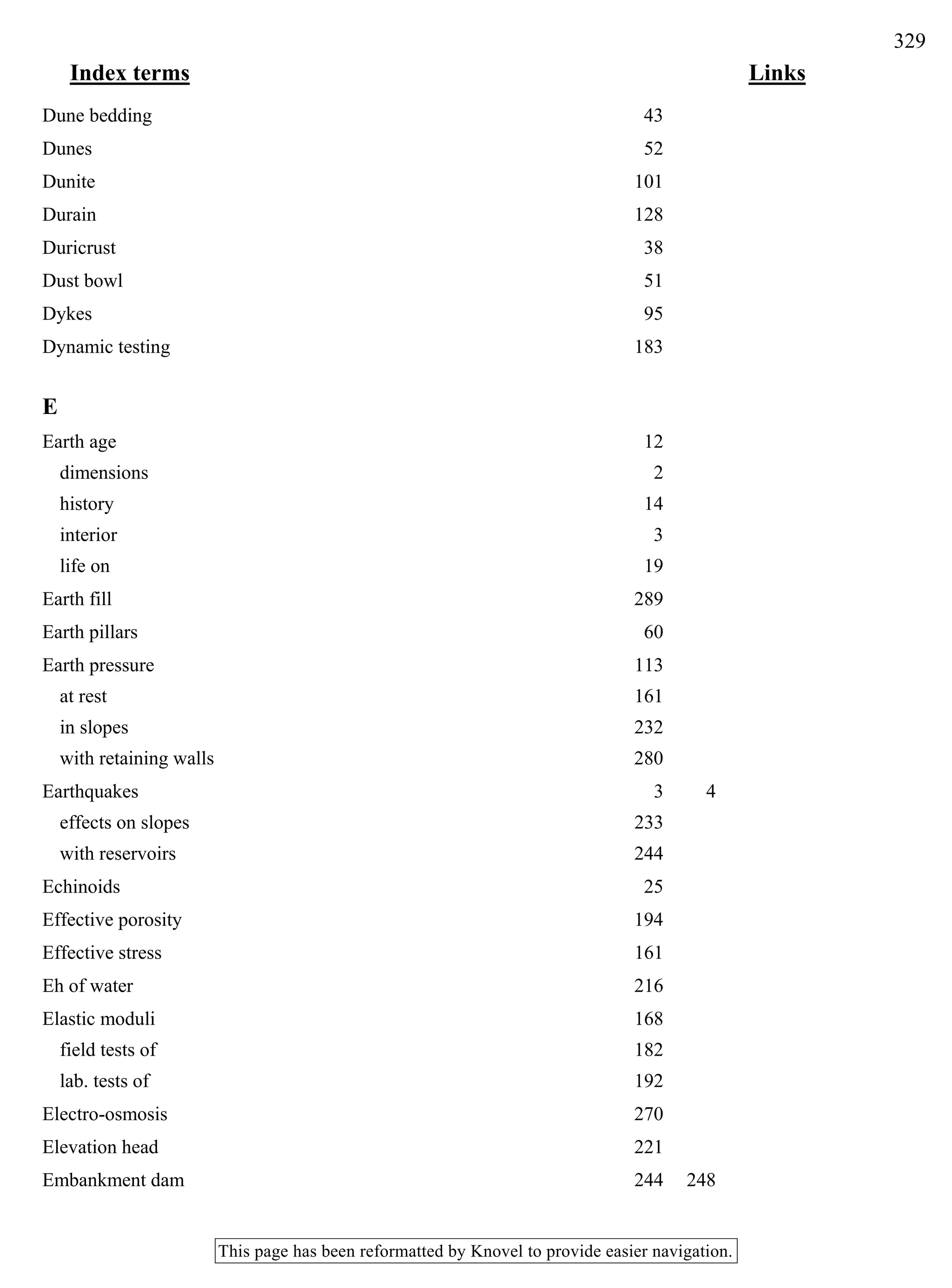

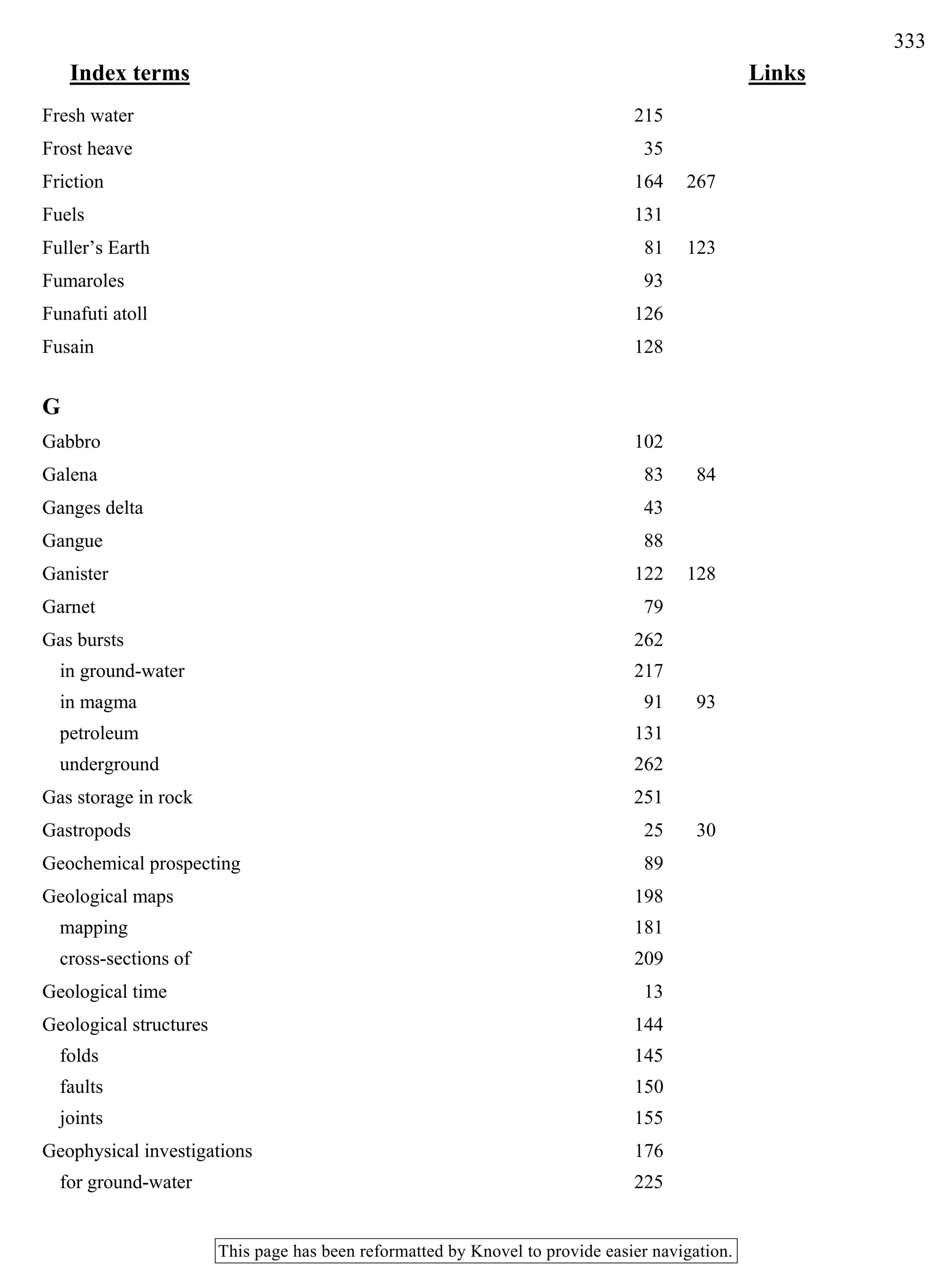

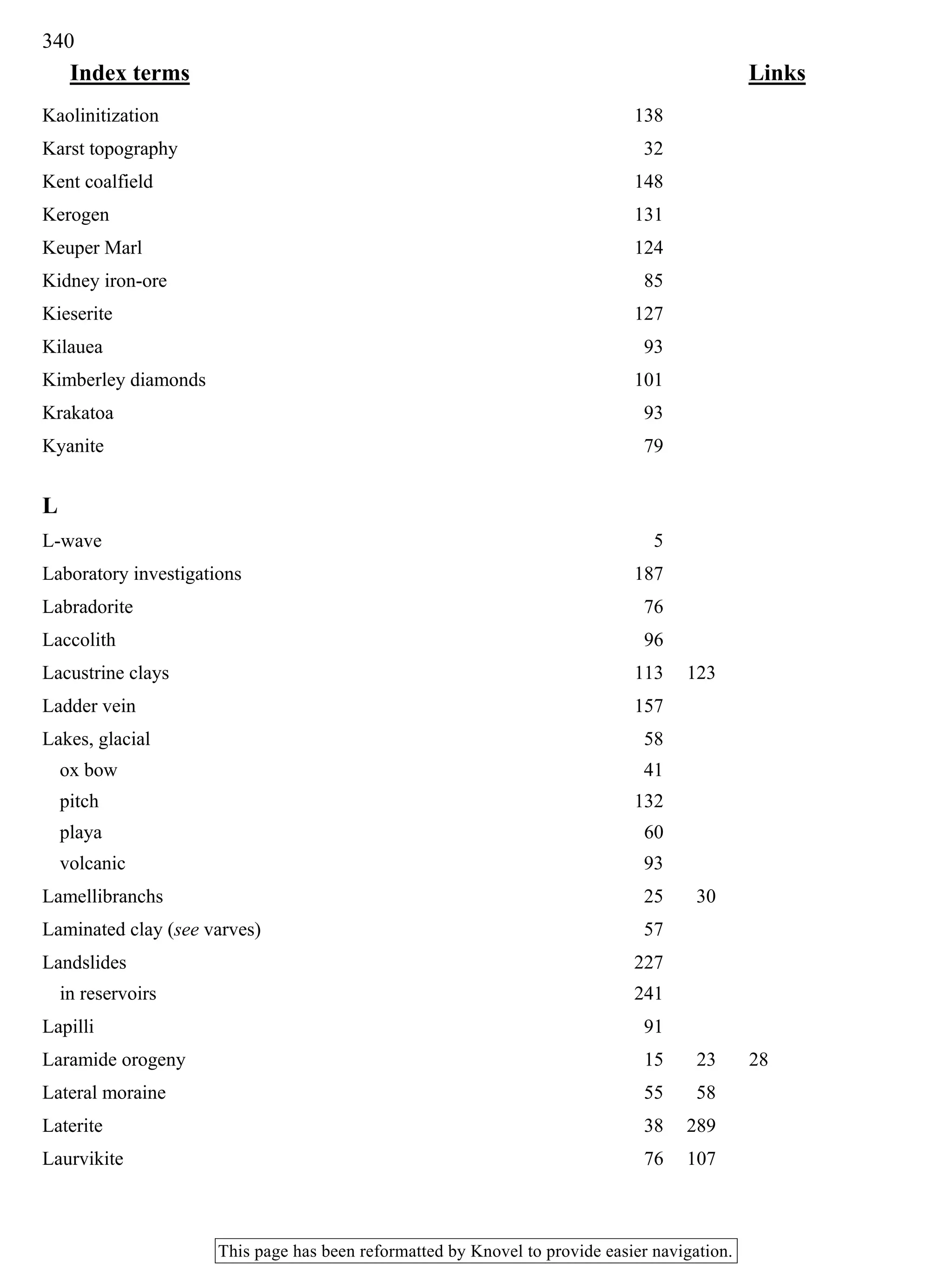

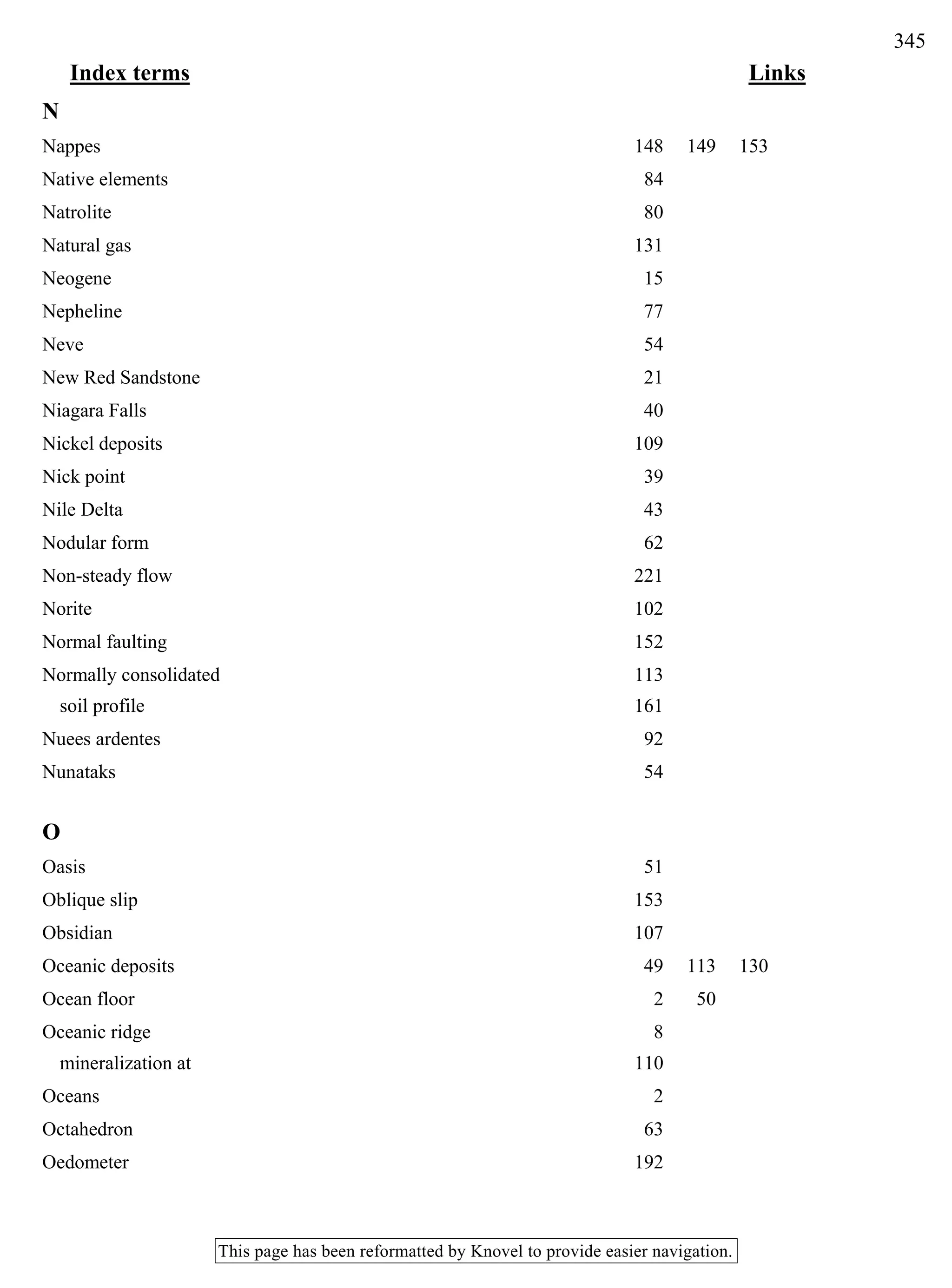

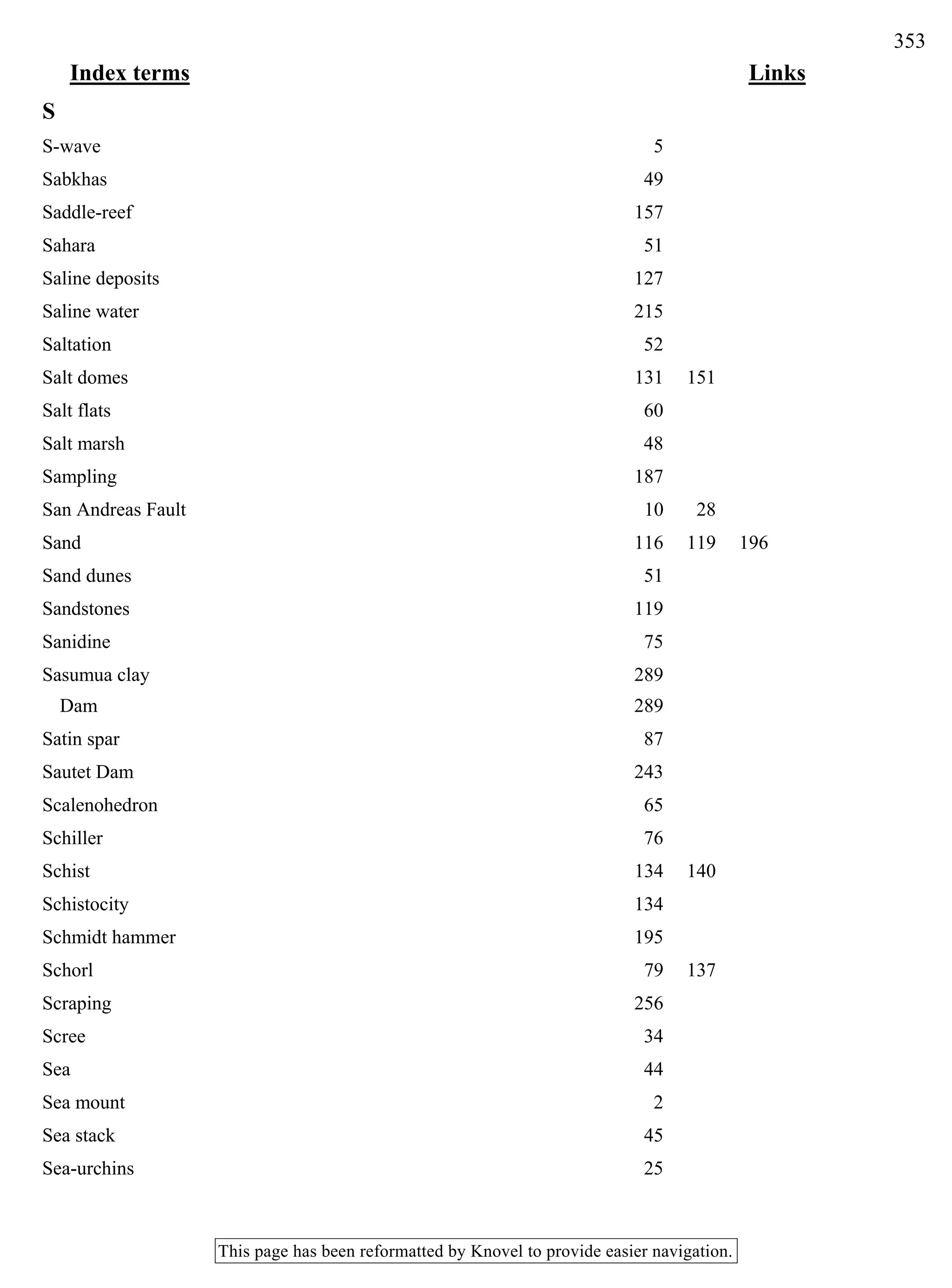

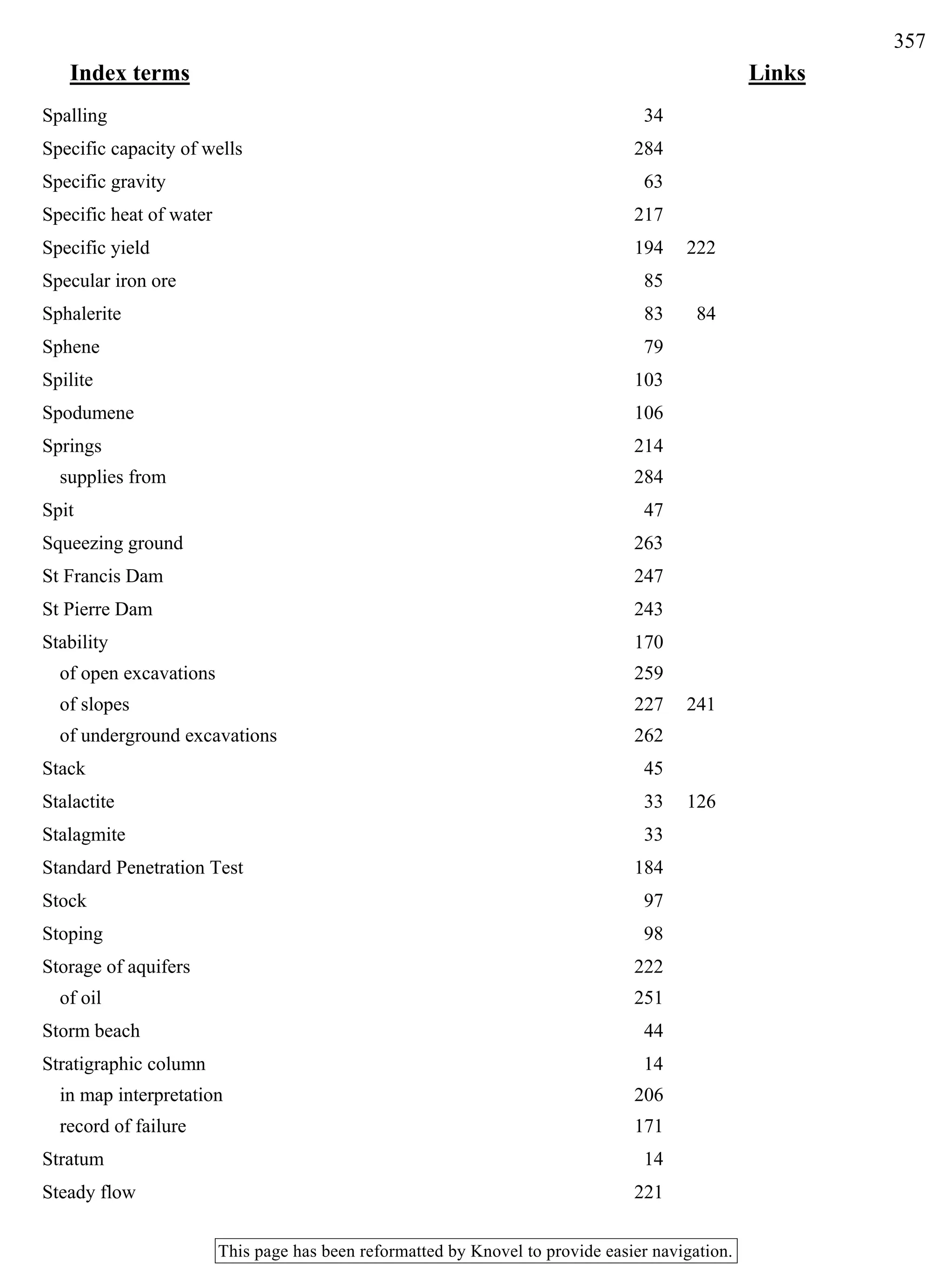

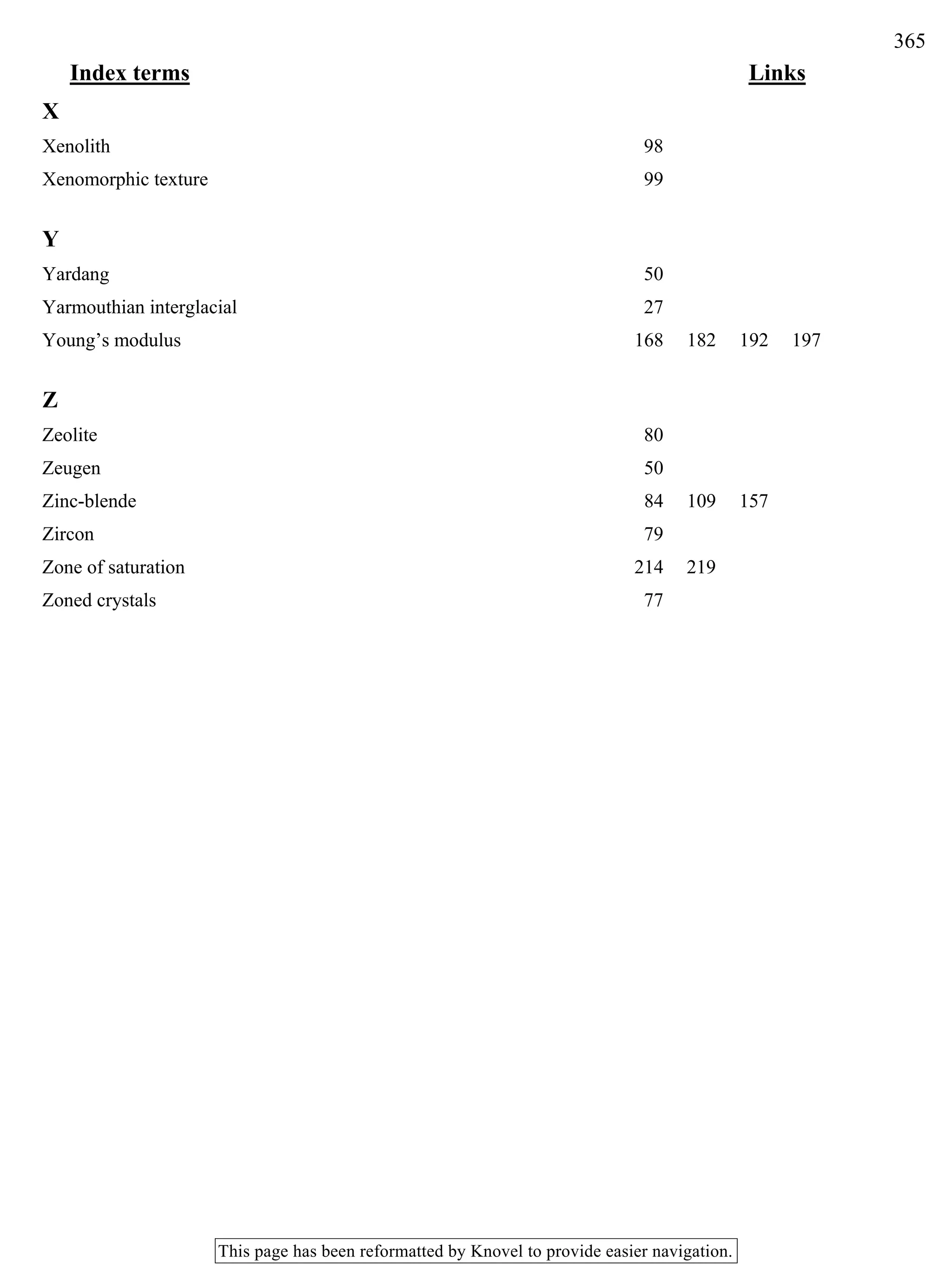

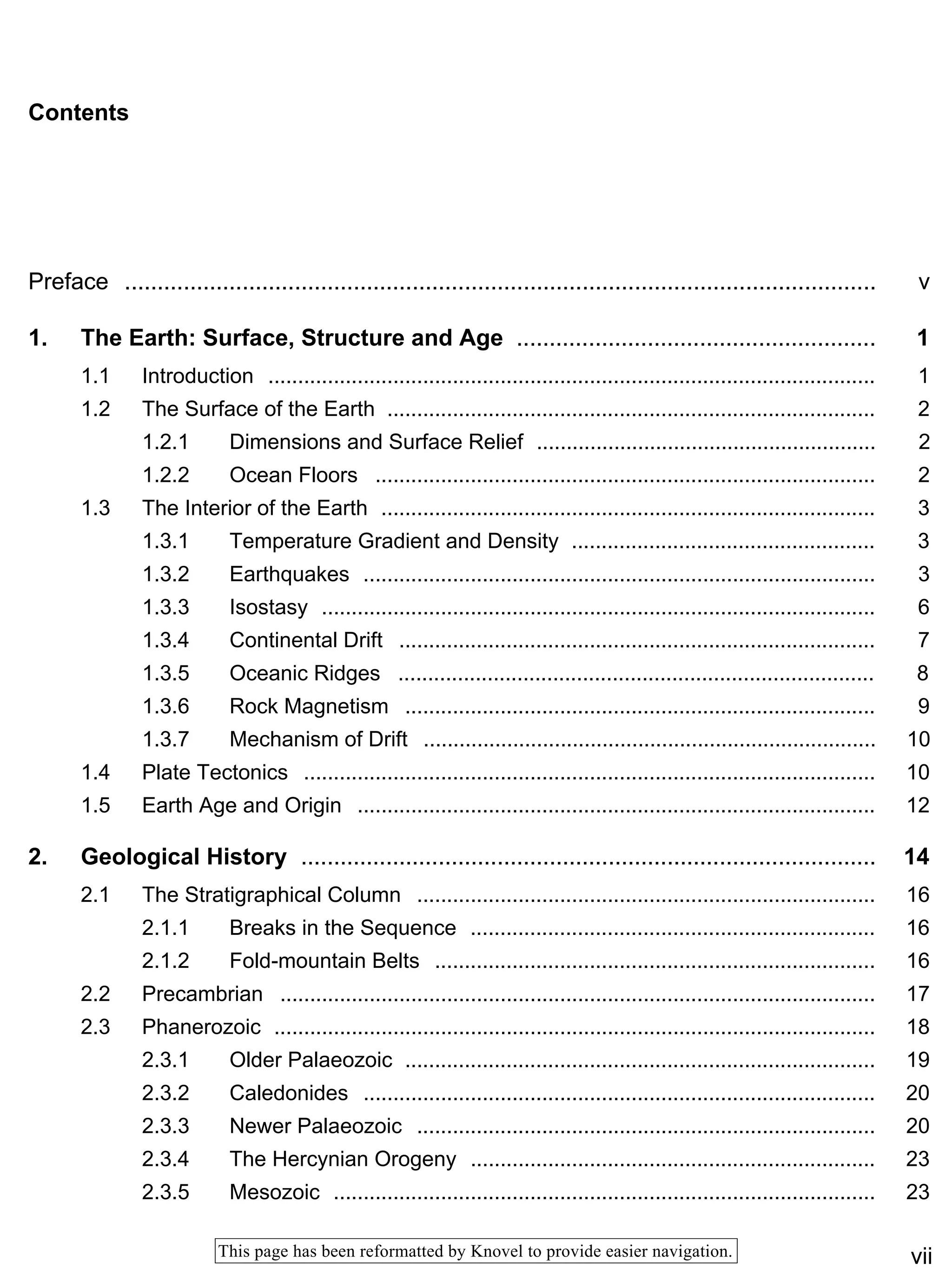

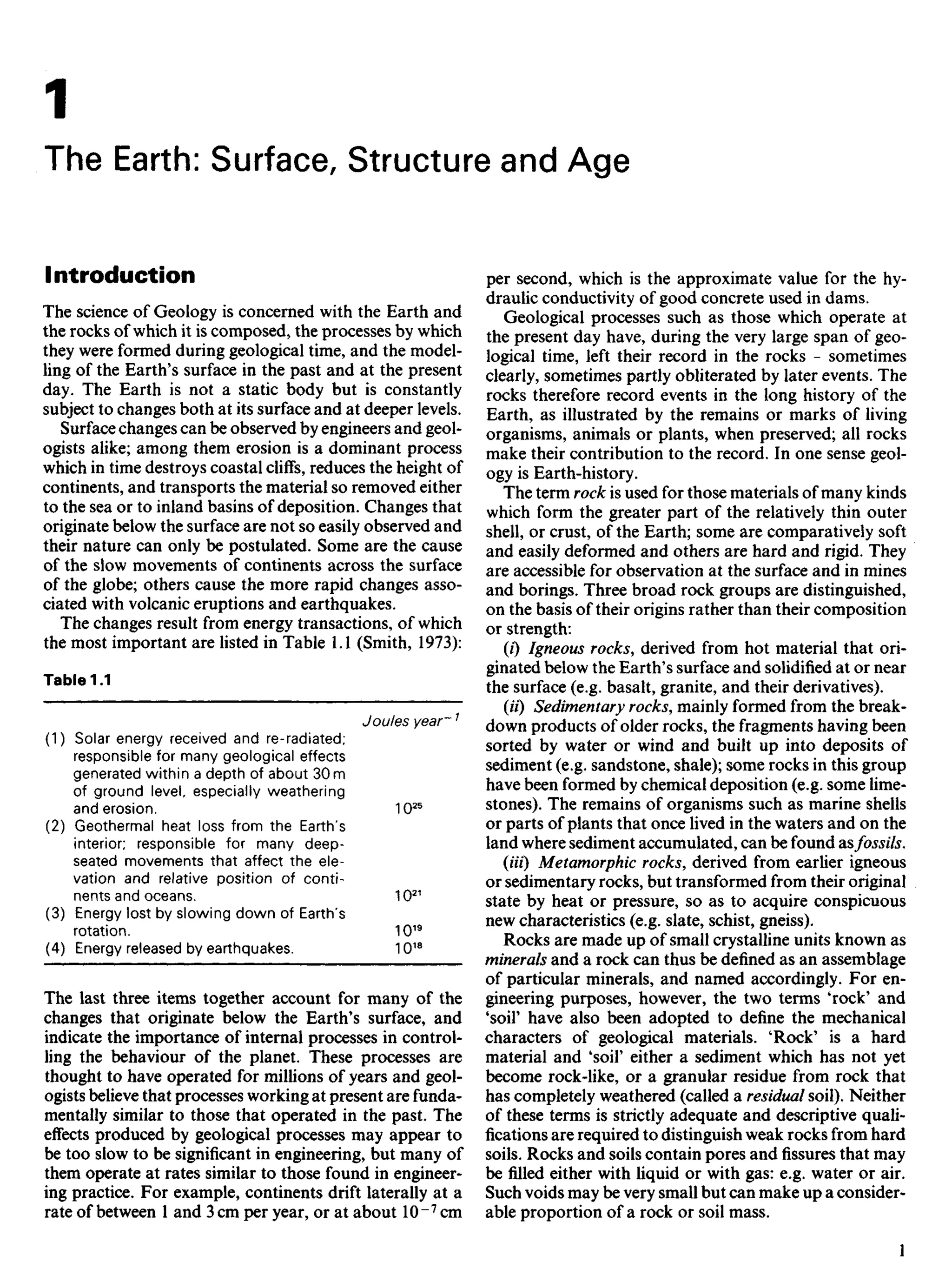

![18

Development and Redevelopment

The development of a community may be influenced by

many geological phenomena, for example, earthquakes

(Chapter 1), weathering and erosion (Chapter 3), volcan-

oes (Chapter 5), landslides and avalanches of rock and

soil (Chapter 14). To these obstacles may also be added

the problems of engineering with the materials and land-

scape created by geological processes, for example, the

difficulty of creating reservoirs (Chapter 15), and of ex-

cavating routes for communications (Chapter 14 and 16).

These, and other examples, are mentioned in previous

Chapters, as indicated.

In this Chapter we wish to describe those geological

factors that affect (/) the provision of an adequate supply

of water from underground sources; (//) the suitability of

minerals, sediments and rocks as materials for the con-

struction of engineering structures; (Hi) the design of

foundations that will safely transfer to the ground the

load of the structure they must carry, and (iv) the safe and

controlled disposal of waste, on land.

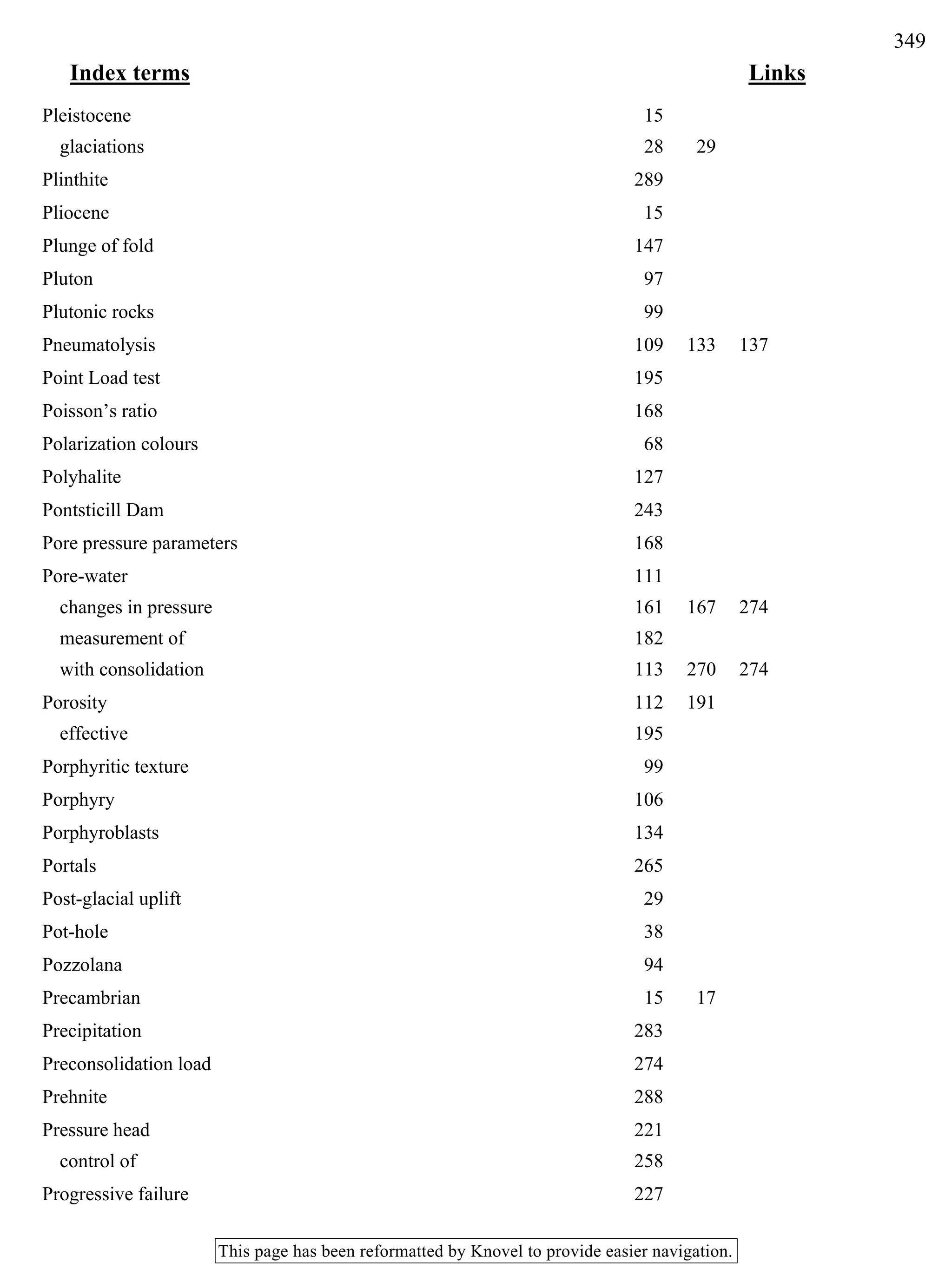

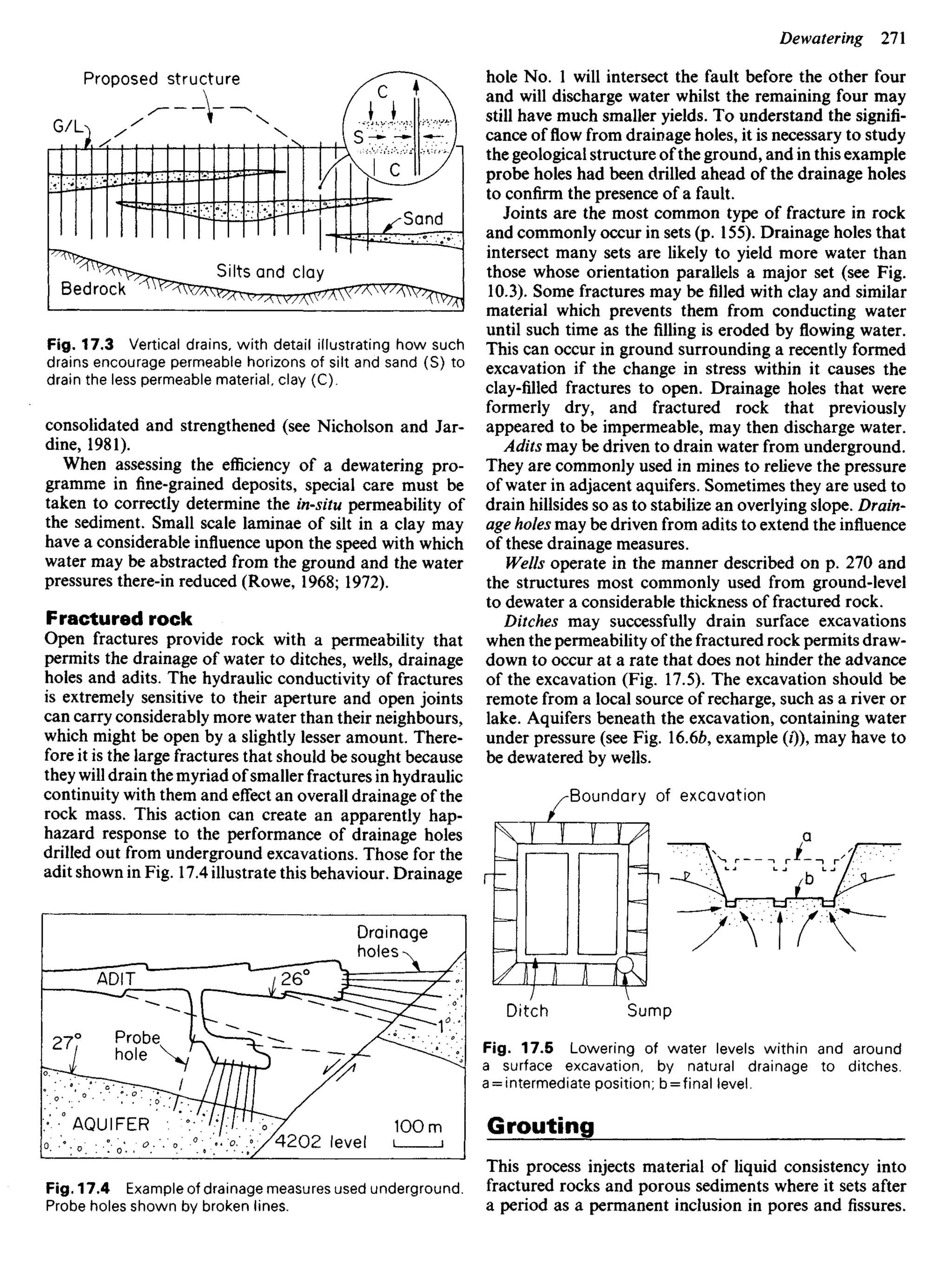

Water supplies

Most ground-water supplies tap localflowsof circulating

meteoric water (p. 213 and Fig. 13.3) that exist within the

catchment over which rain has fallen.

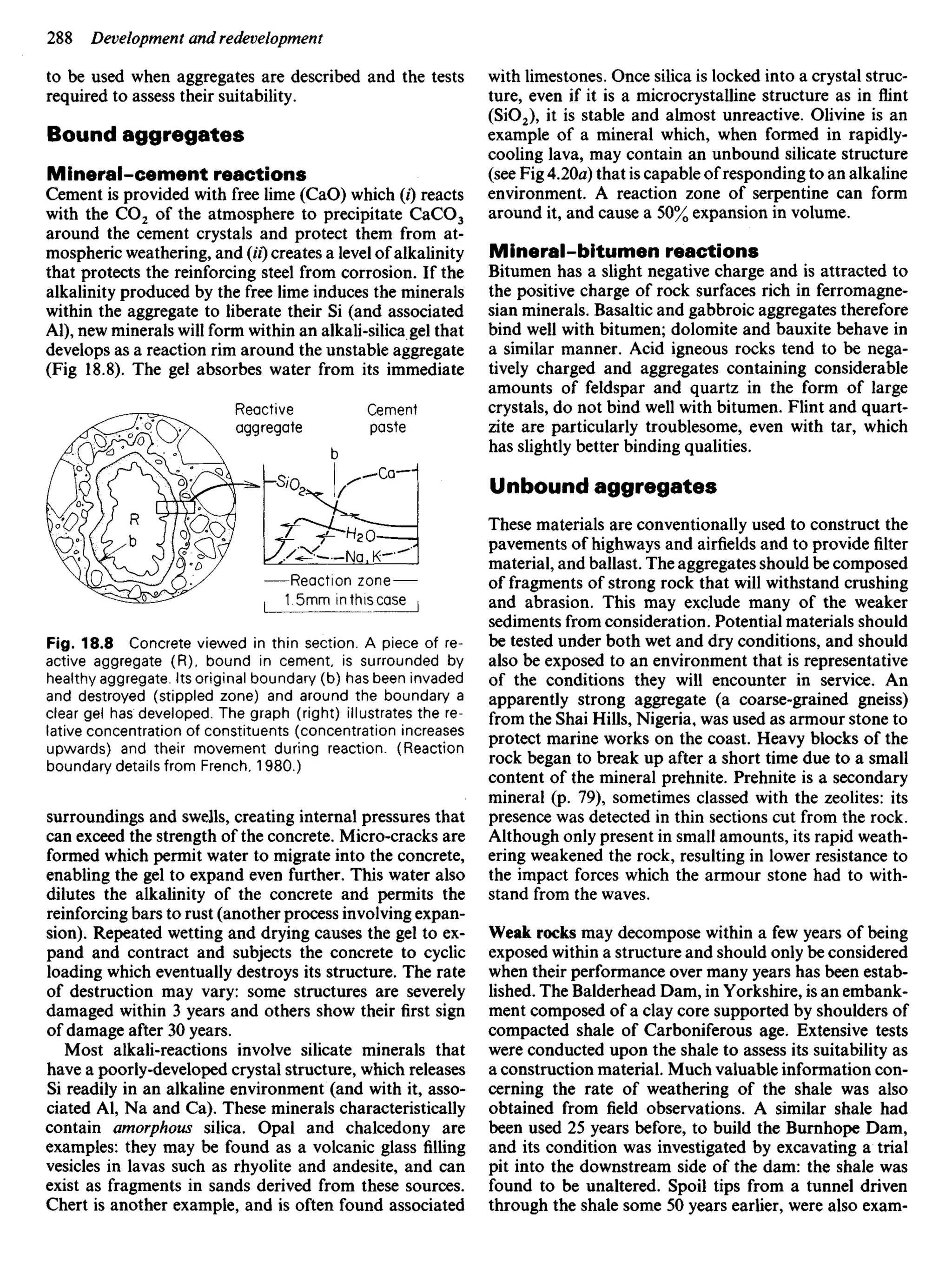

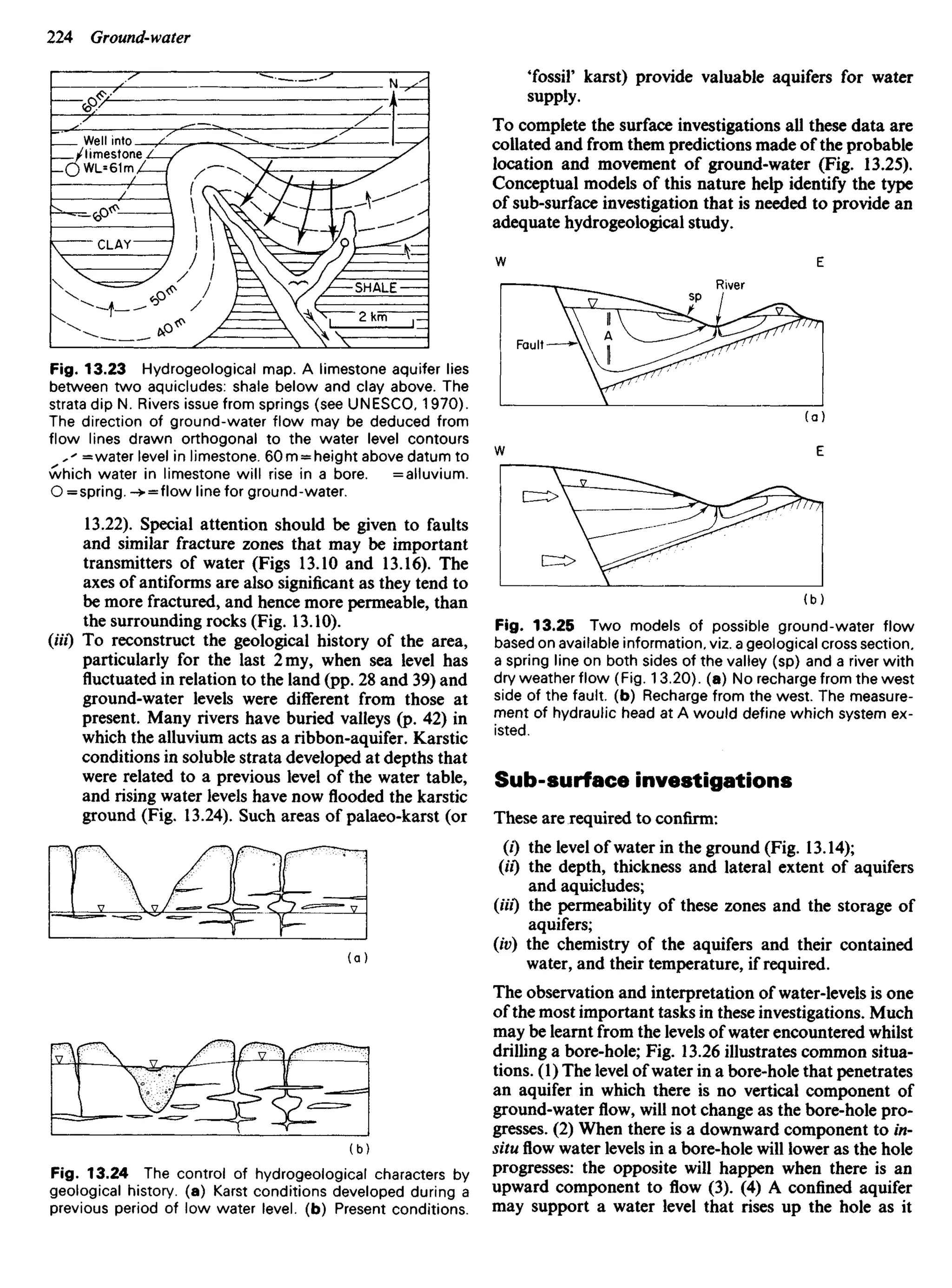

Catchments

Two types of catchment must be recognized, namely sur-

face and underground.

Surface catchments are bounded by the highest ground

separating neighbouring drainage systems. This high

ground is called the surface-divide or watershed. Rain

falling on an impermeable catchment will drain over its

surface to the river within the catchment.

Underground catchments are defined by water levels, not

ground levels, and are bounded by a line that joins the

highest water levels beneath a surface catchment. This

line is called the ground-water divide. Often, the boundary

of the underground catchment lies almost vertically be-

neath that of the surface catchment, and rain percolating

to the water table will be carried by ground-water flow

towards the river draining the surface catchment (see Figs

13.20« and 13.23). When the position of the divides does

not coincide, rainwater which percolates to the water table

will be carried, by ground-water flow, beneath the divide

of the surface catchment in which it fell: this is called

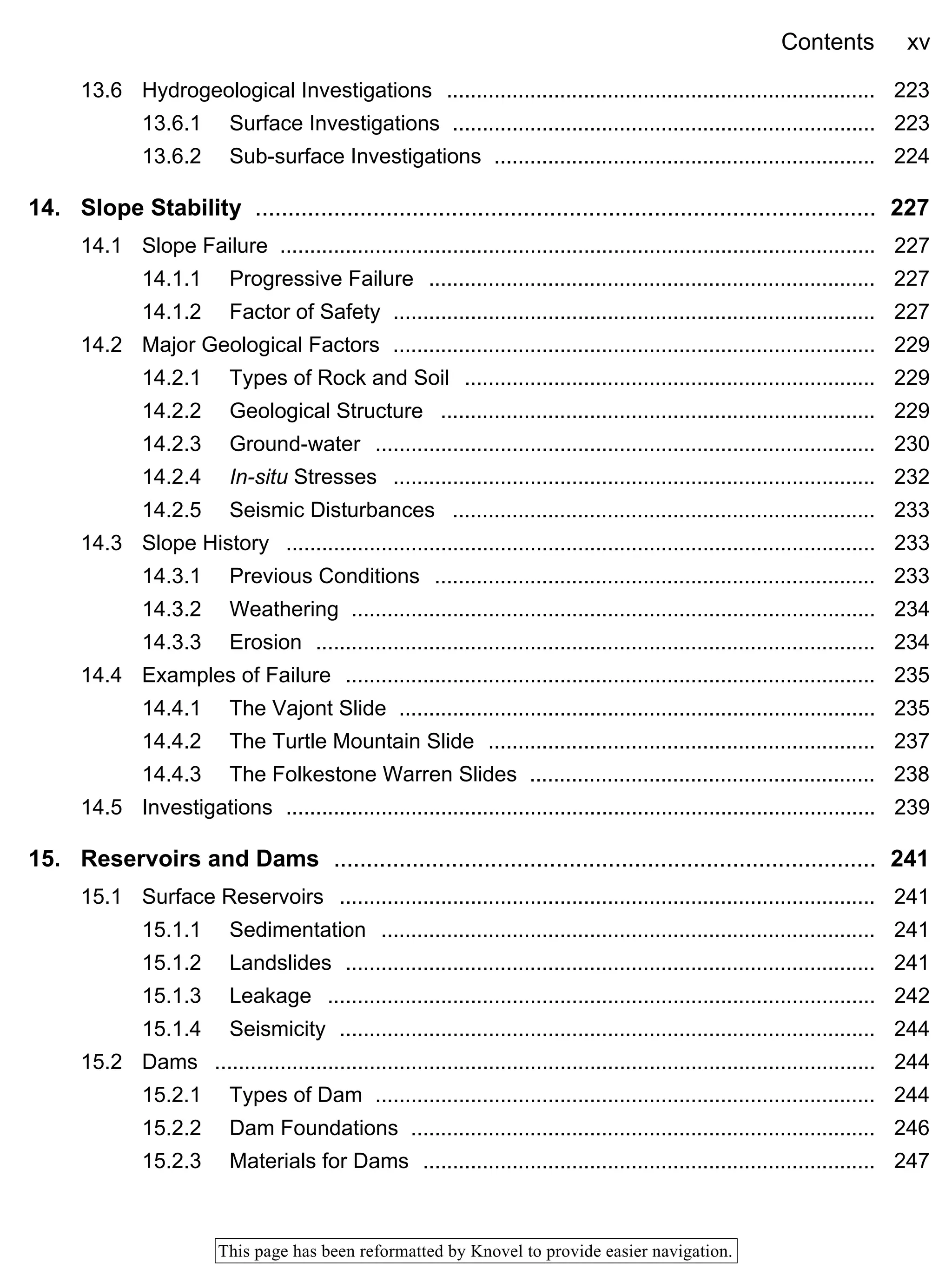

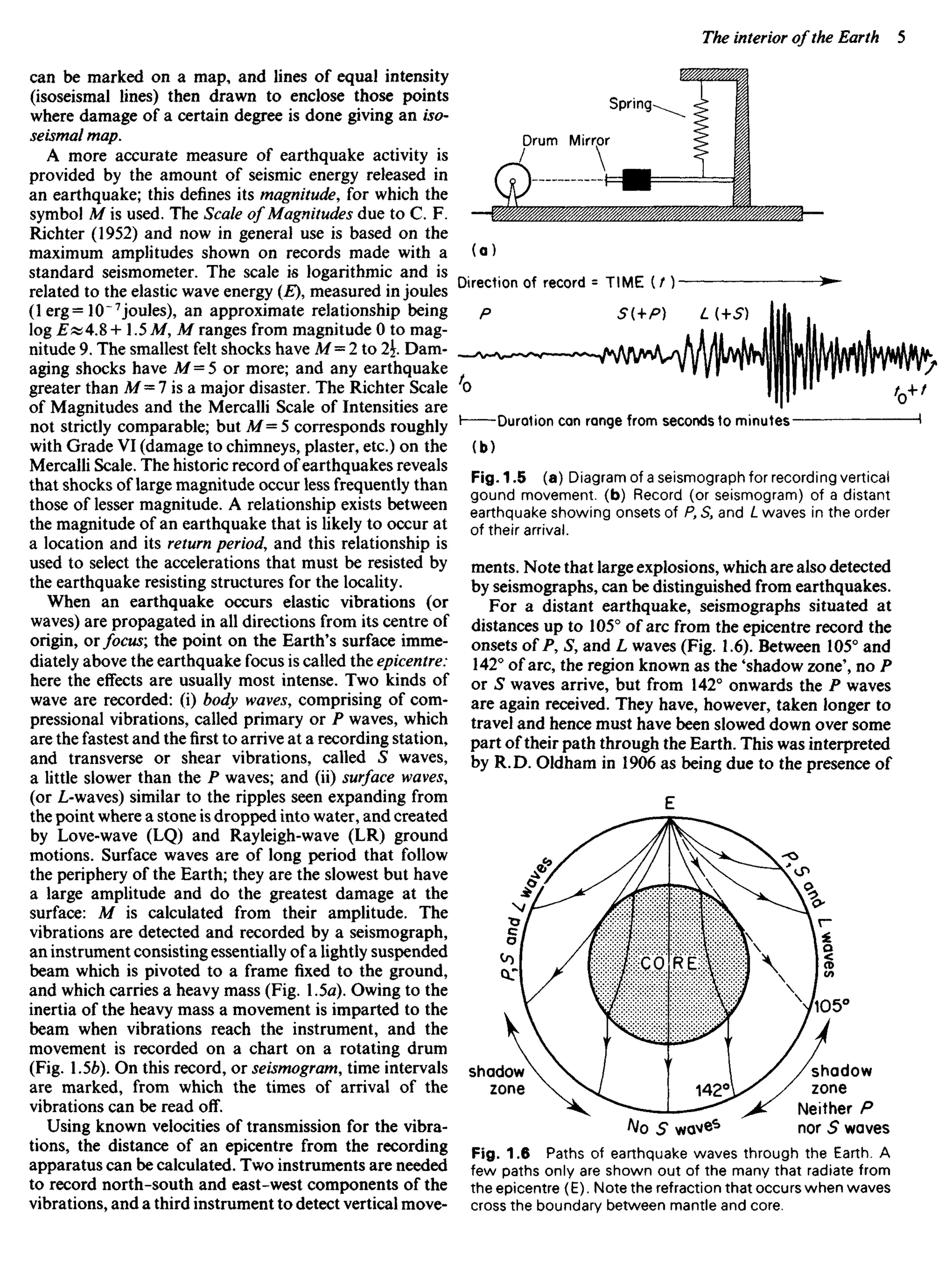

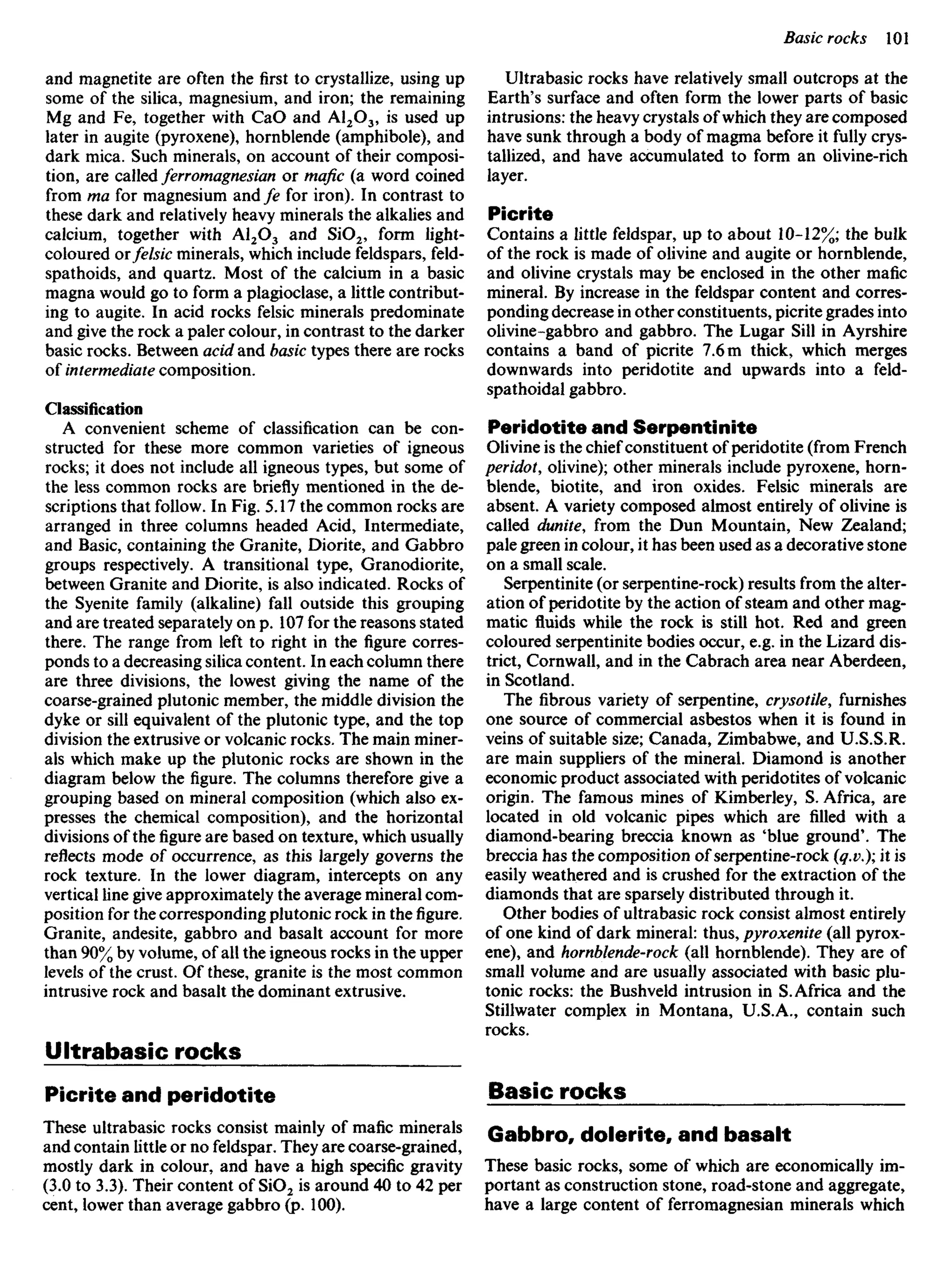

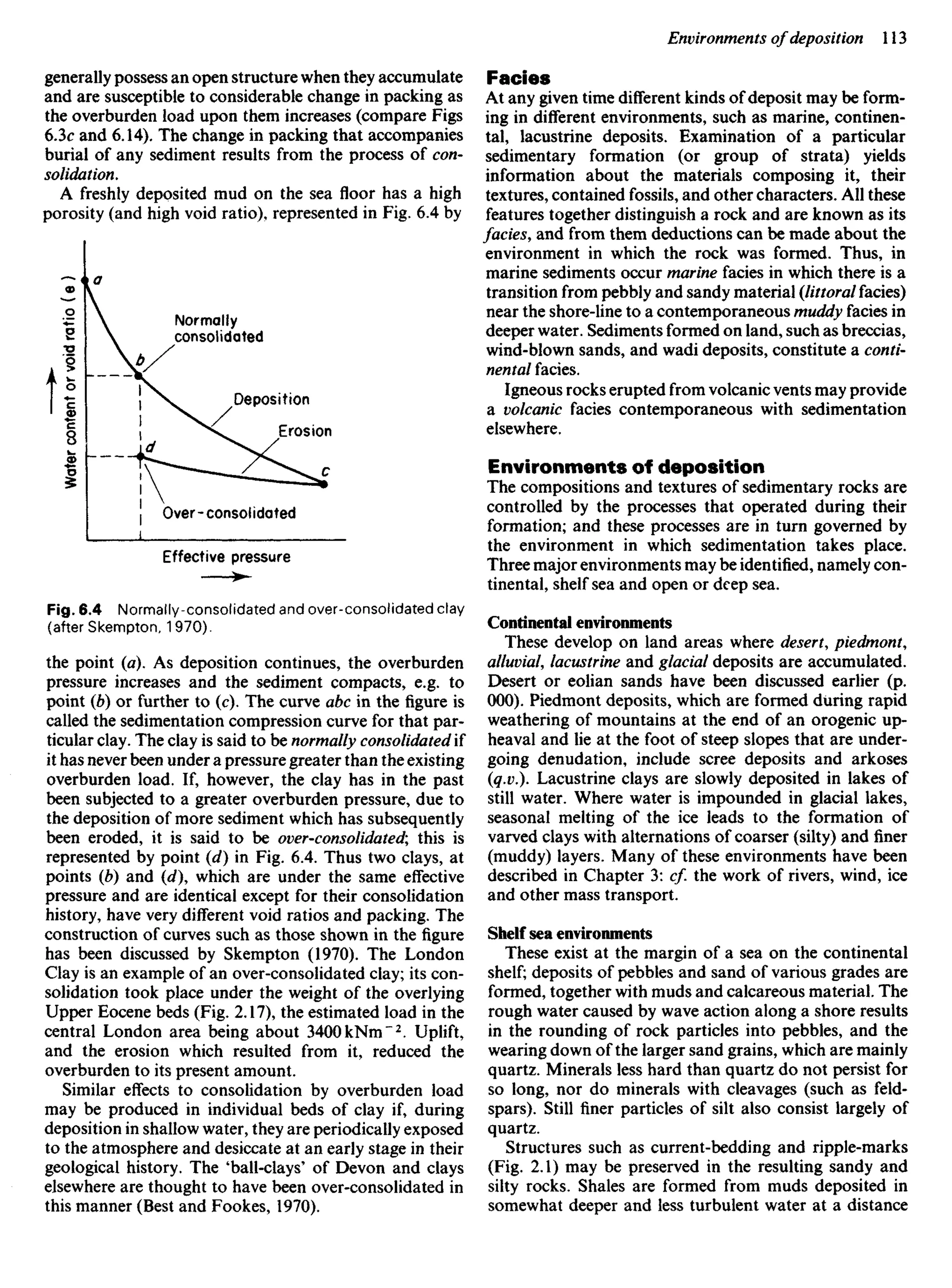

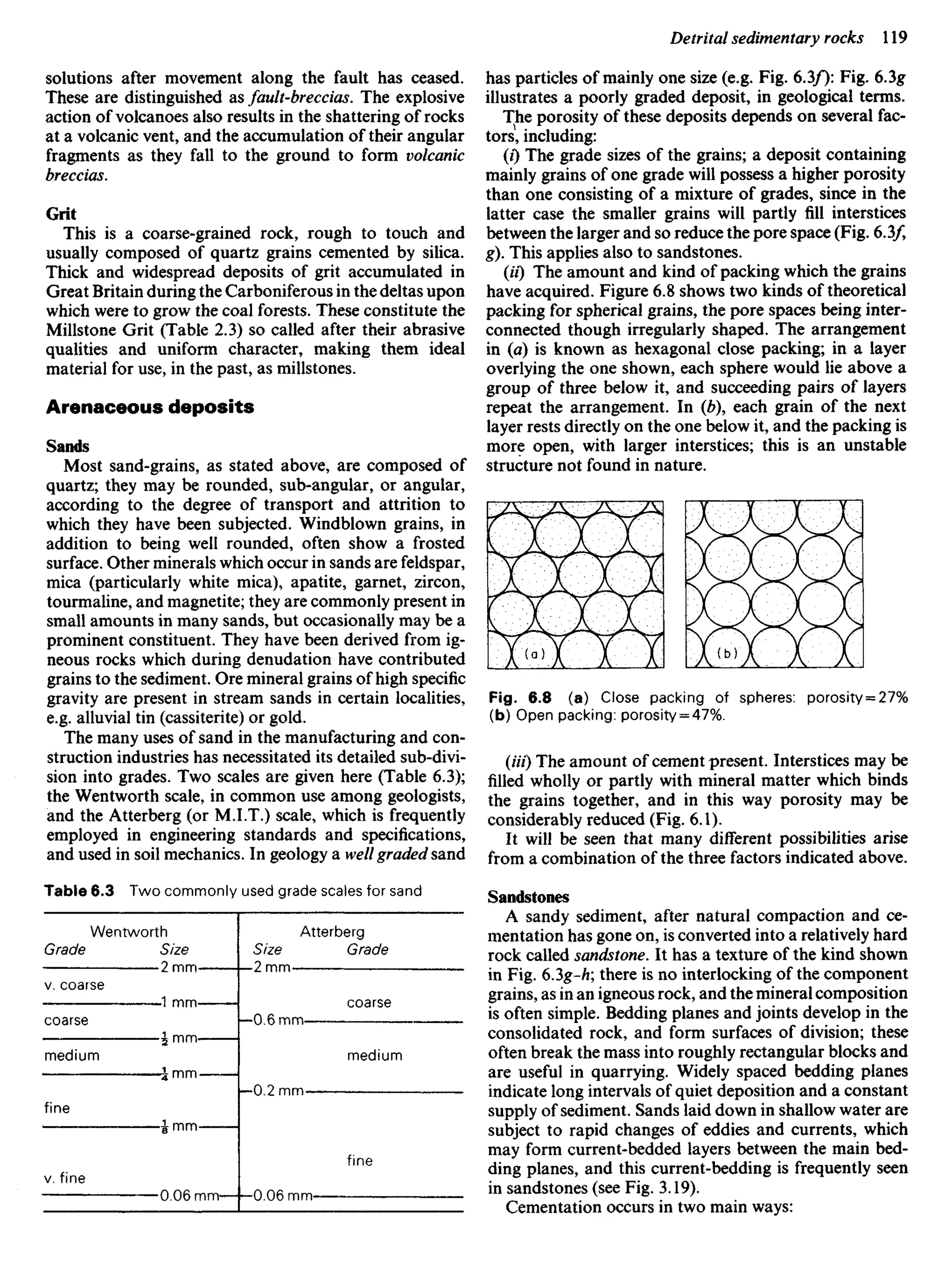

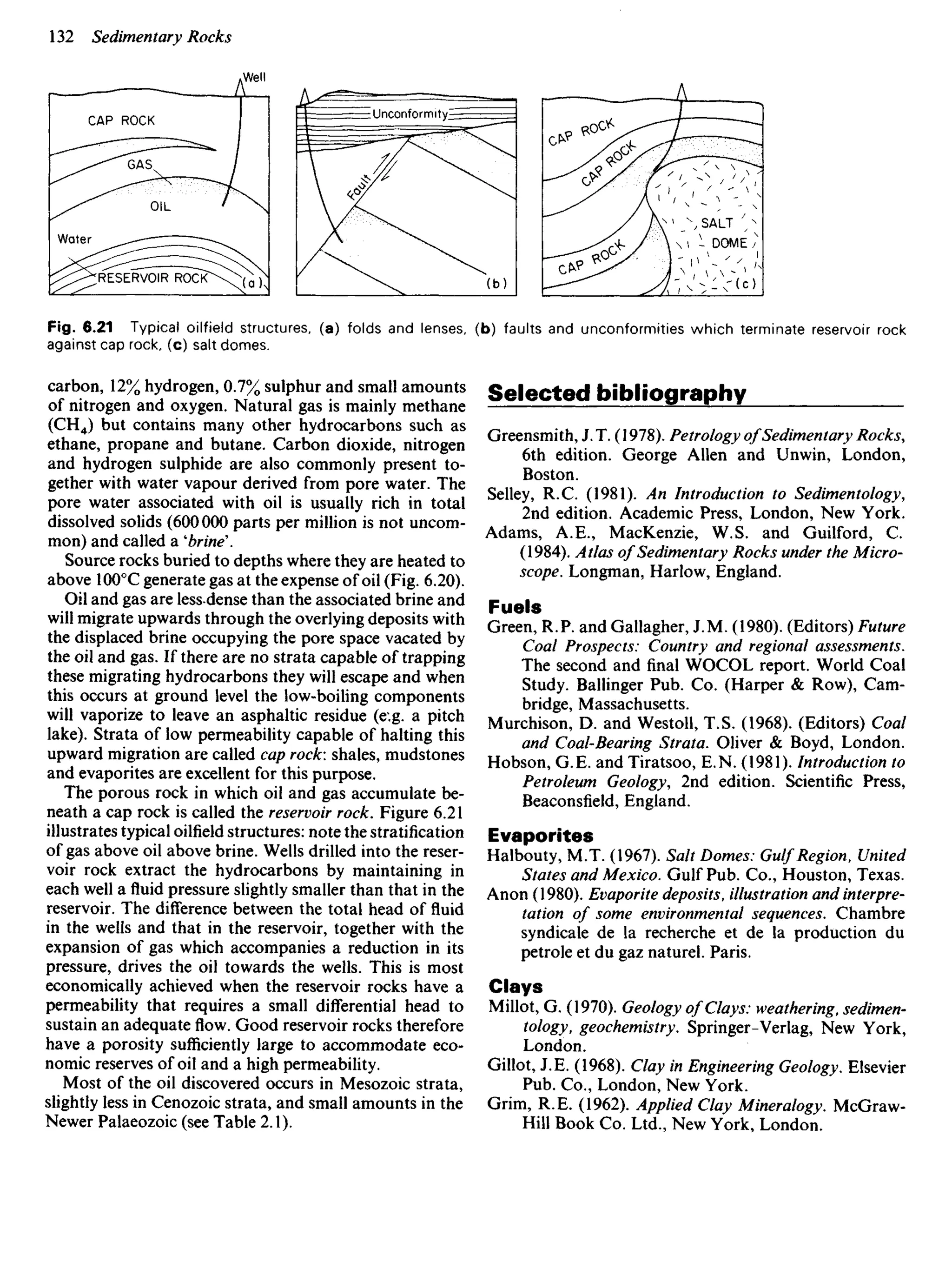

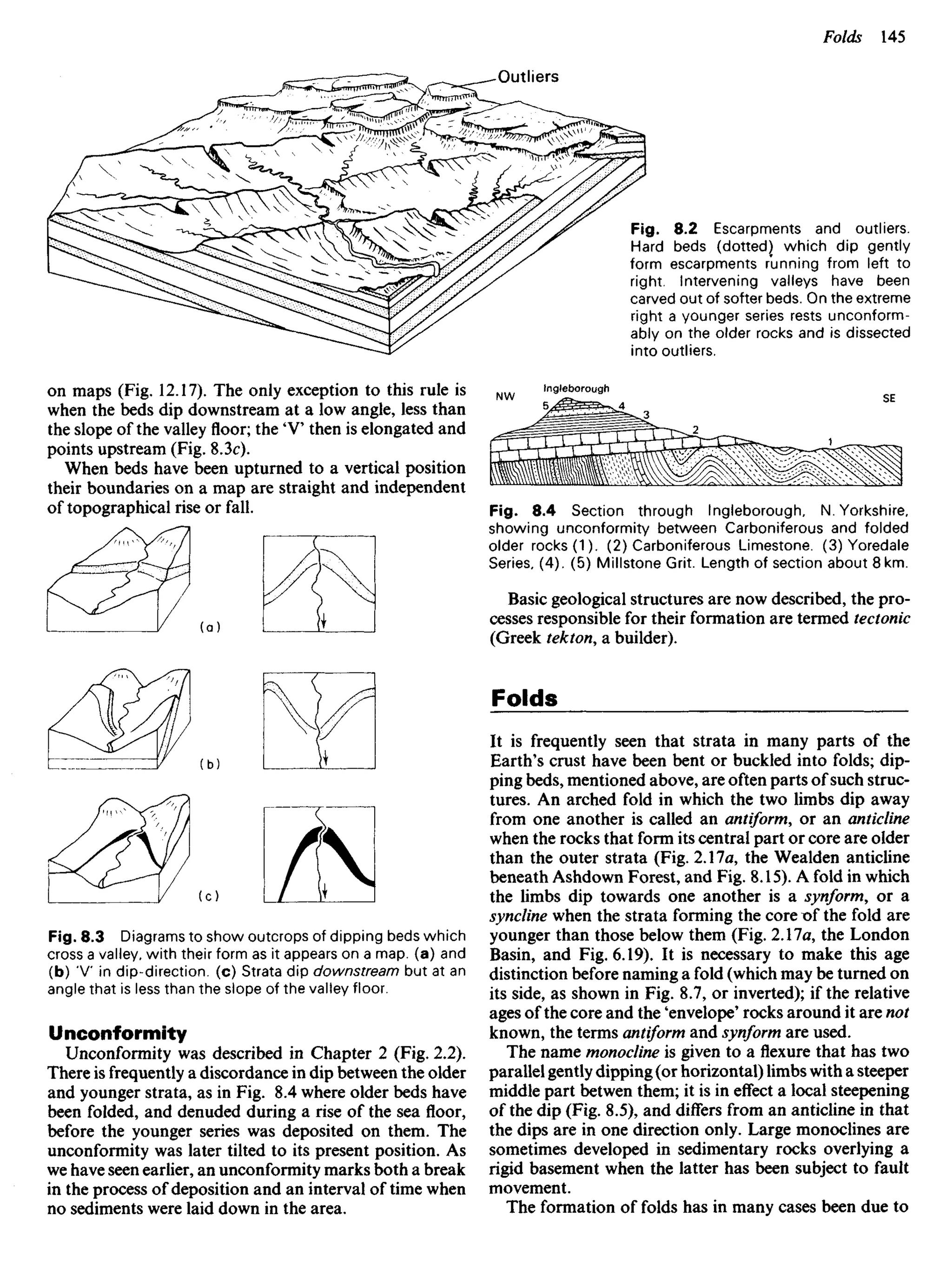

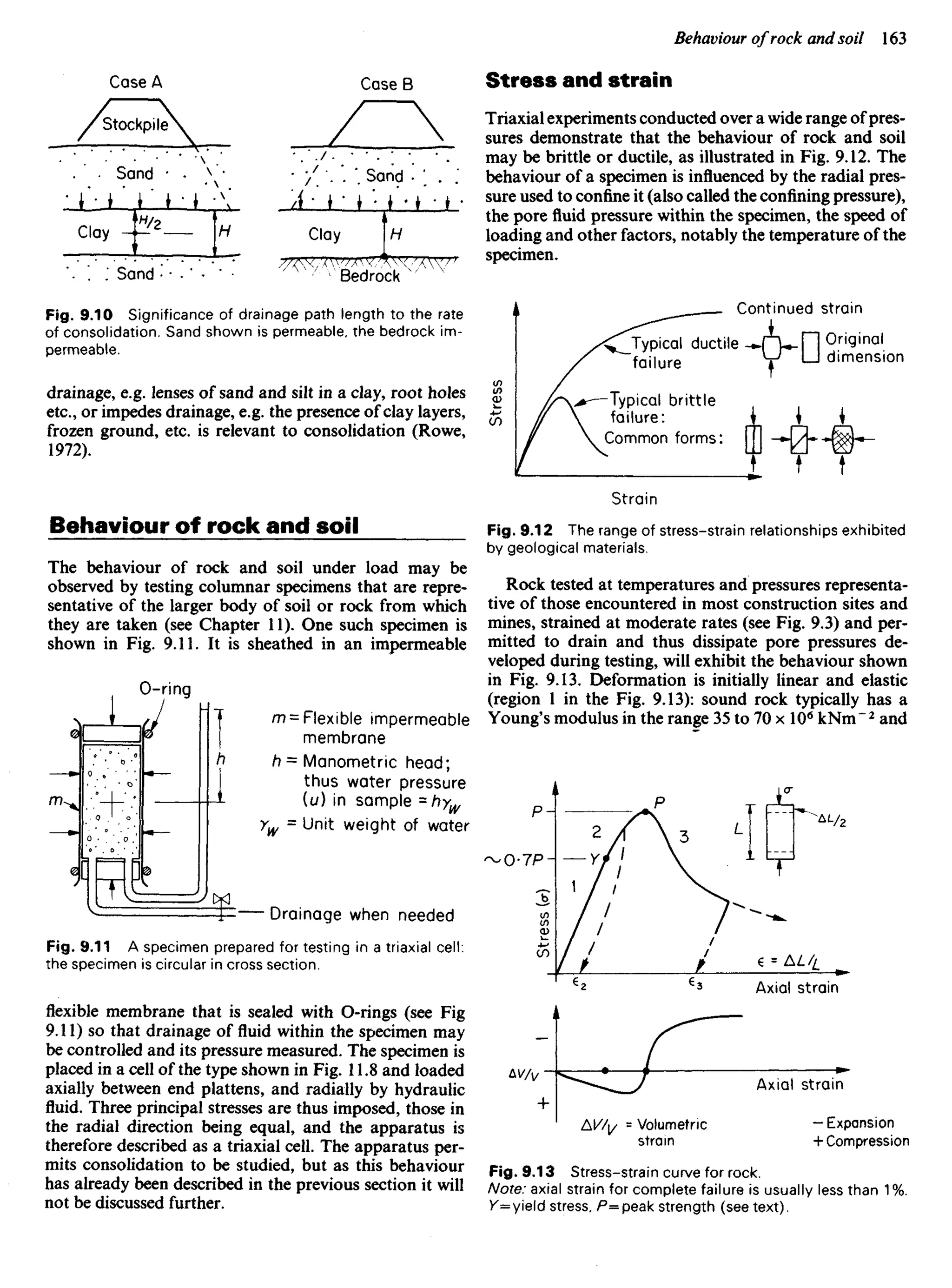

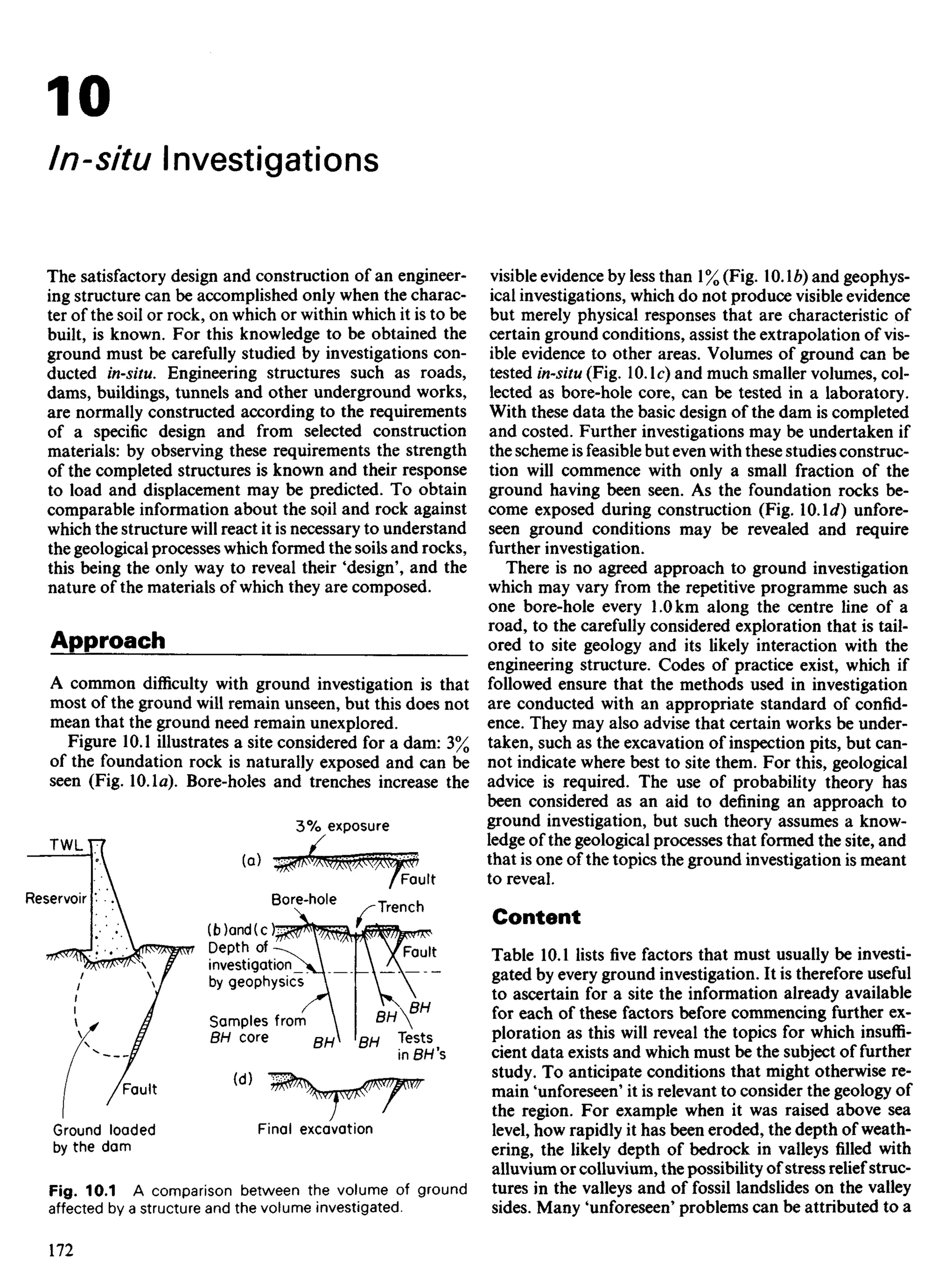

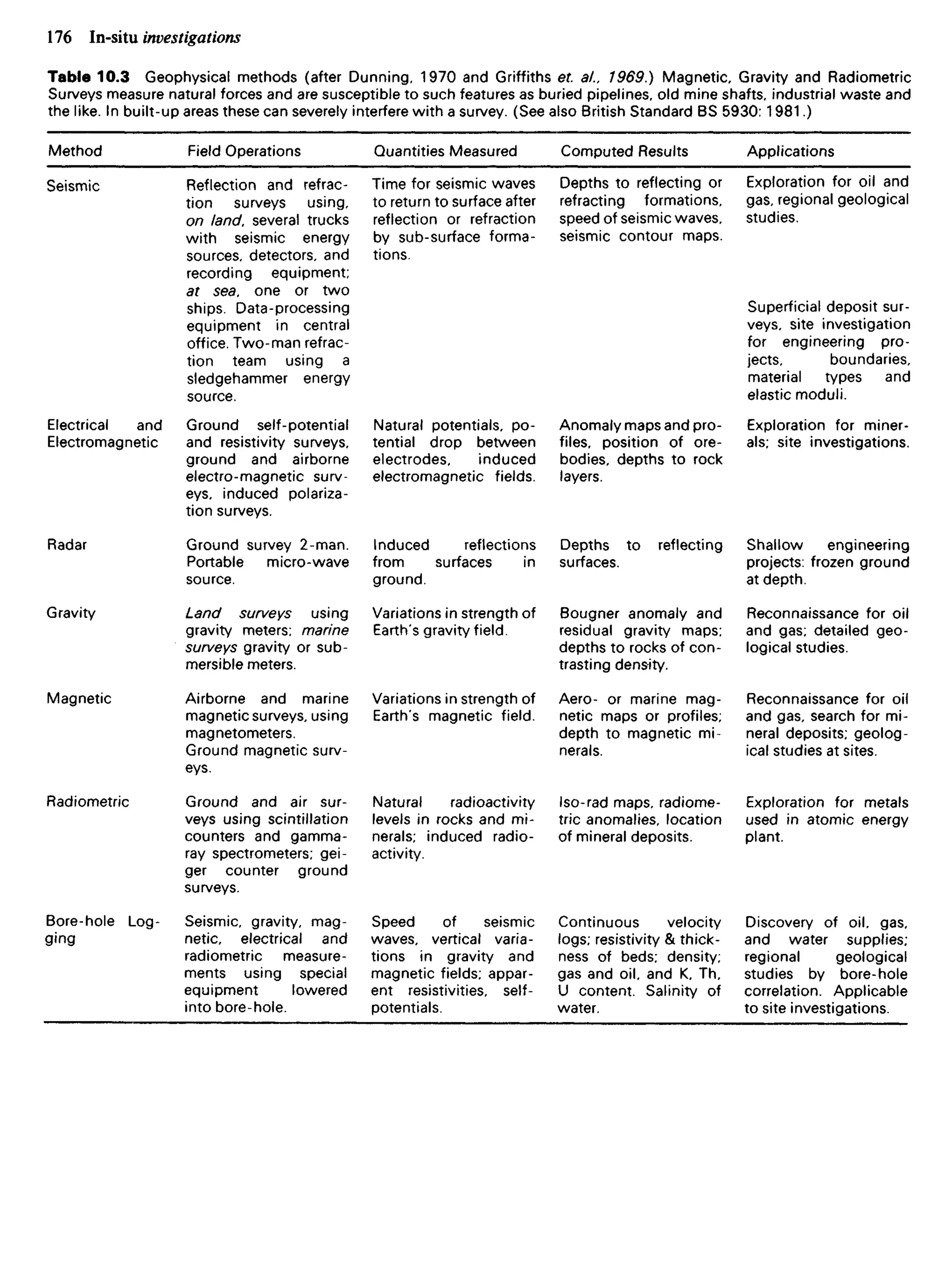

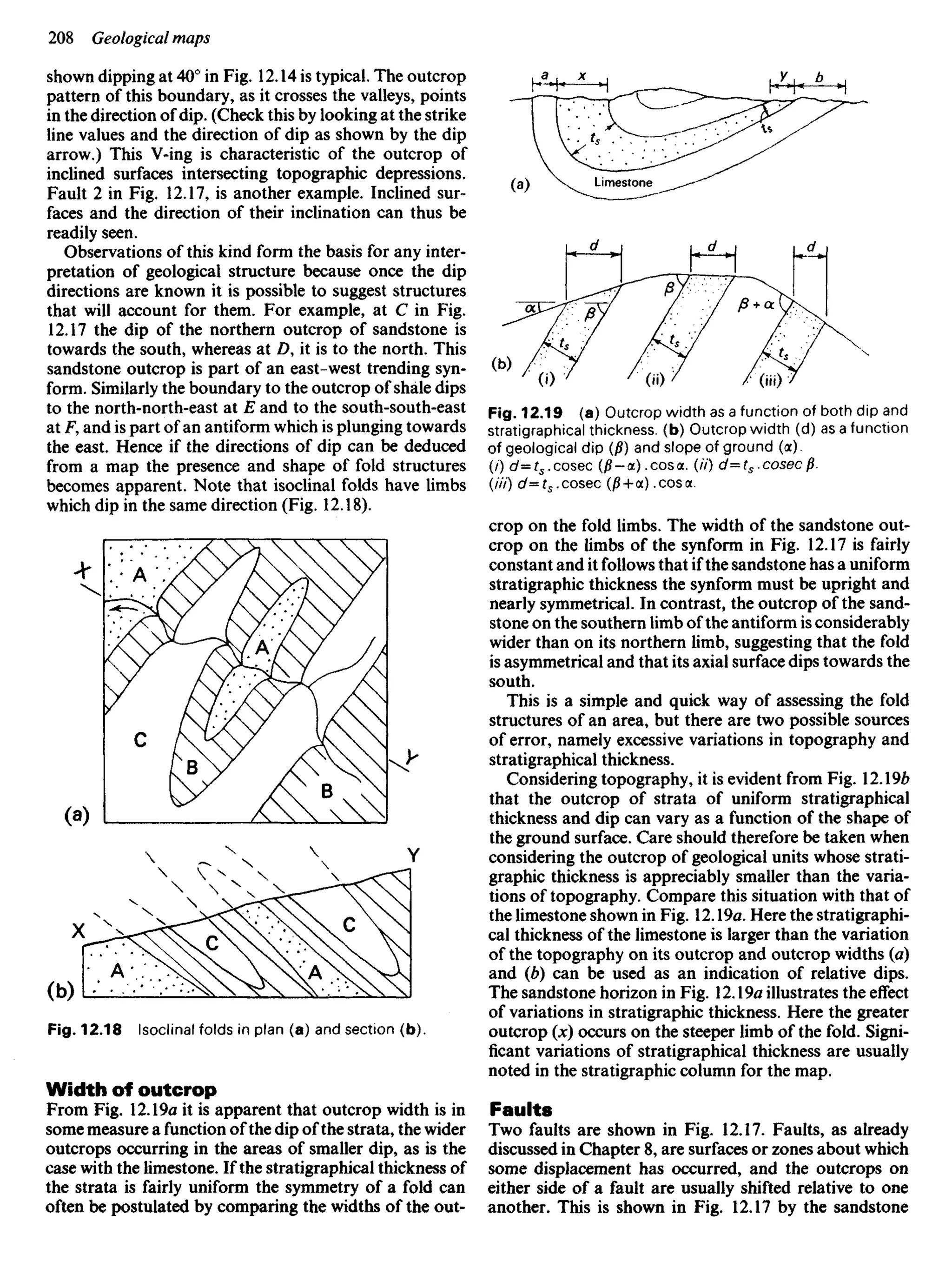

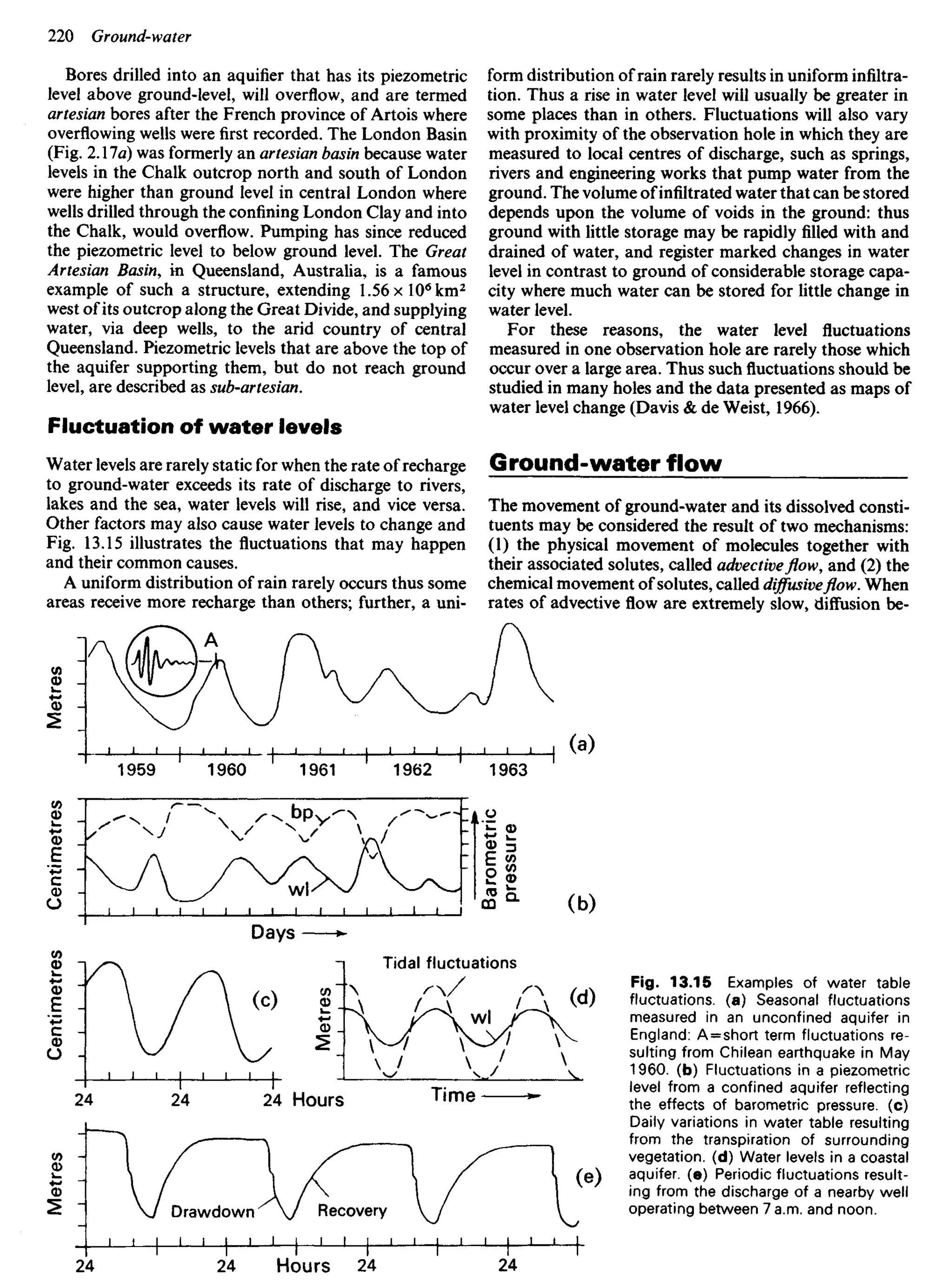

underflow (Fig. 18.1).

Water table

River

River

Fig. 18.1 On the left a map of a catchment: solid

line = topographic divide; broken line = ground-water divide;

arrows indicate underflow. Two vertical cross-sections illus-

trate the geological structures that result in this underflow;

arrows indicate movement of ground-water. GS = gauging

station for measuring river flow.

Water budgets

If more water is taken from the ground than enters it

from recharge (p. 214), water levels will fall and, in theory,

the ground will eventually be drained. The water budget

Table 18.1 Examples of water budgets

Mass balance for a budget

INFLOW =OUTFLOW +CHANGE IN

STORAGE

For a catchment (simple budget)

Precipitation = Evaporation + ^

Transpiration+ +Infiltration

River run-off J

For a catchment (more complex budget)

'evaporation+ ^

transpiration +

River run-off+ r Infiltration+ ^

Precipitation+ ^ pumped net change in

+ ve underflow+^= Jg r o u n d w a t e r + U J lake levels+ }

imports of water J ] _v e under- I artificial

flow+ exports I recharge J

of

, water

For an aquifer

Recharge =Ground-water+ Changes in

discharge water level x

coef, of storage](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ageologyforengineersseventhedition-240123054612-a0c16209/75/A_Geology_for_Engineers_Seventh_Edition-pdf-266-2048.jpg)