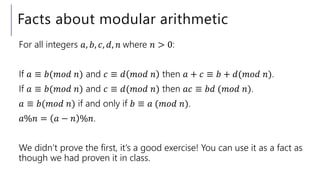

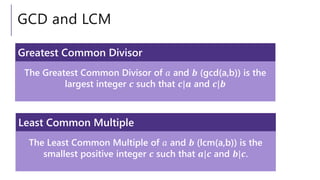

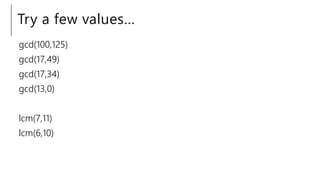

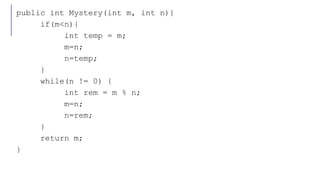

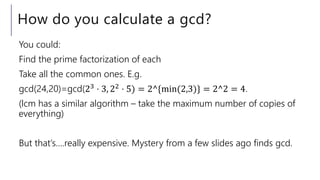

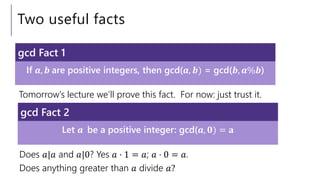

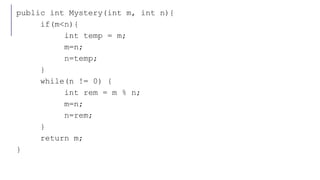

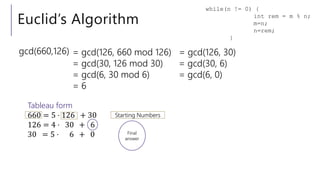

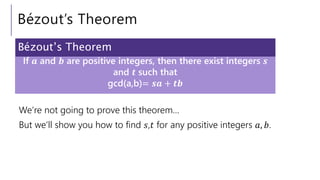

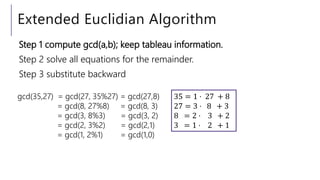

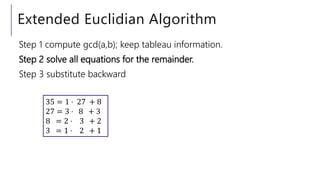

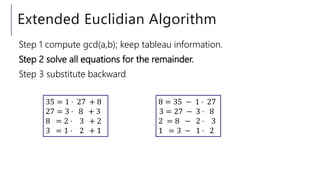

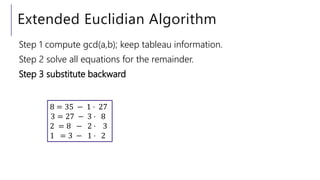

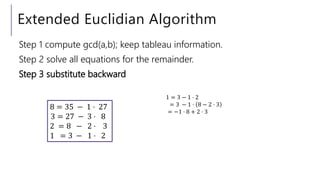

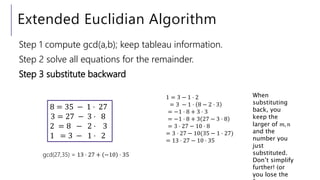

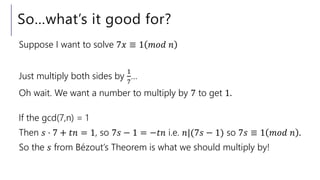

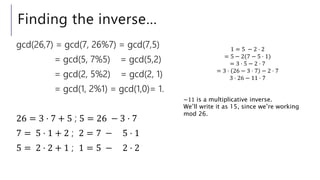

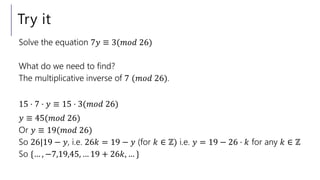

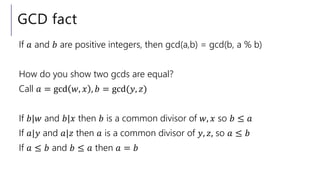

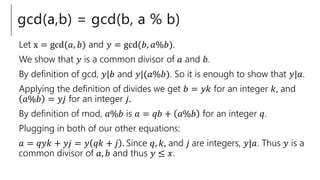

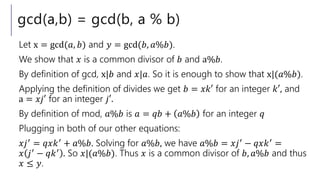

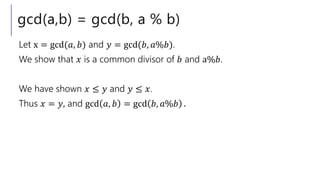

The document discusses Euclid's algorithm for finding the greatest common divisor (GCD) of two integers. It explains that Euclid's algorithm repeatedly finds the remainder of dividing the larger number by the smaller number, then sets the smaller number equal to the larger and continues, until finding the GCD. The document also introduces Bézout's theorem relating the GCD of two integers to their linear combination, and extends Euclid's algorithm to solve for the coefficients in Bézout's theorem.