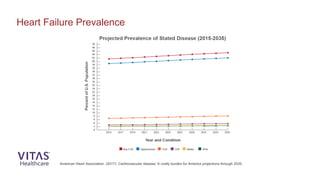

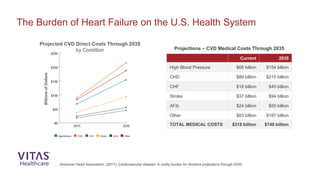

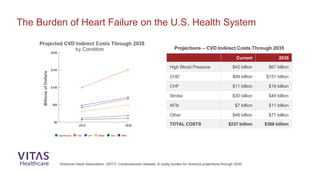

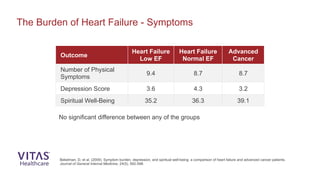

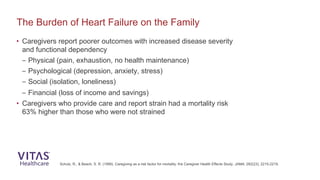

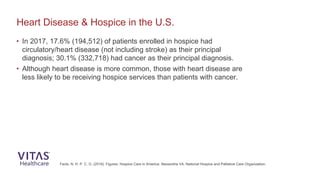

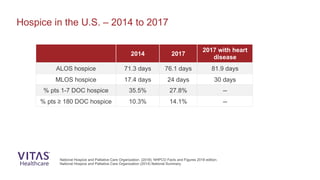

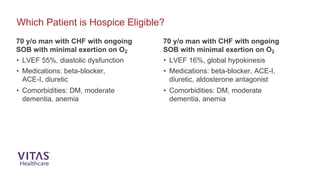

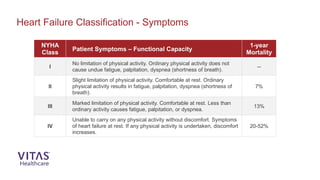

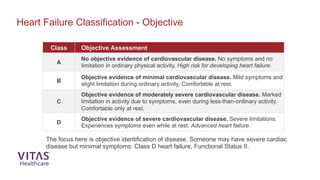

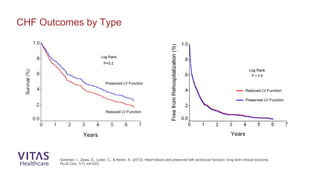

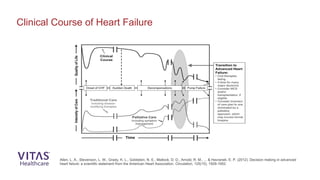

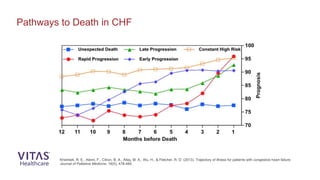

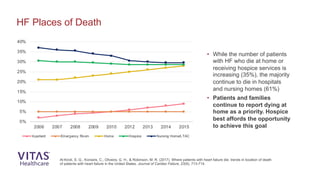

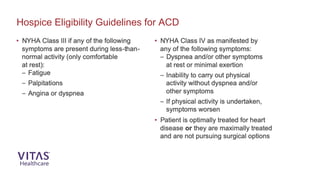

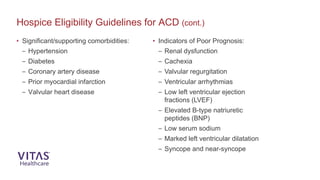

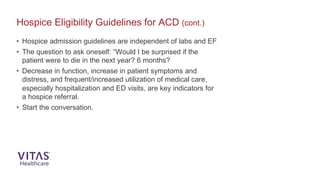

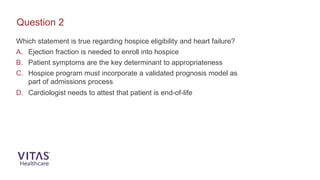

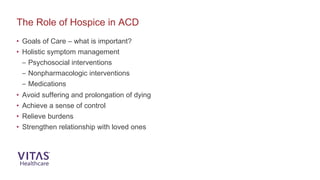

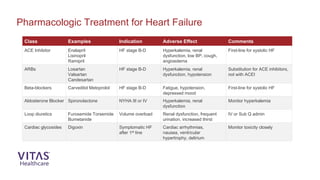

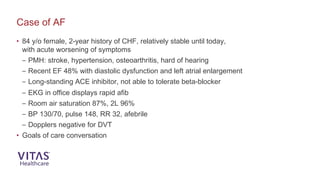

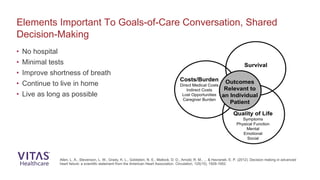

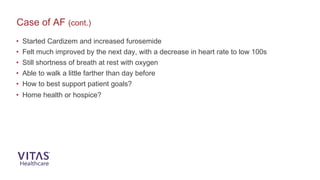

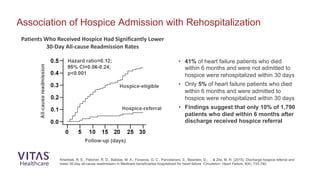

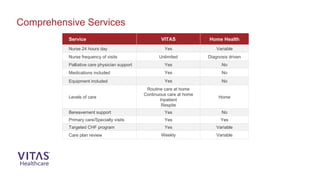

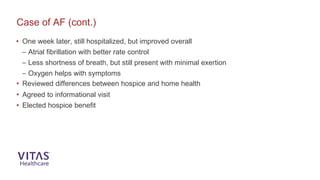

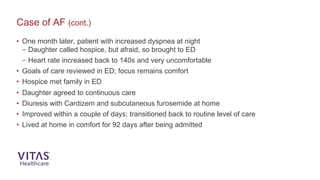

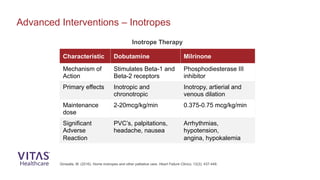

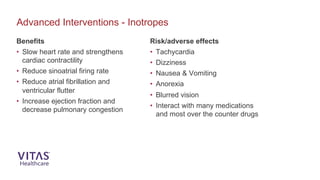

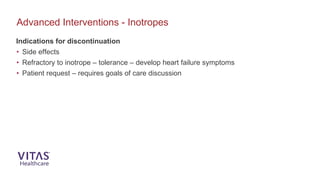

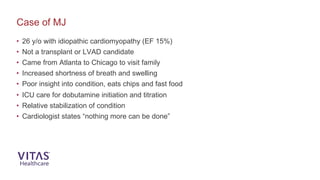

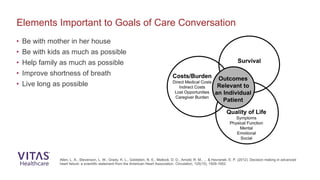

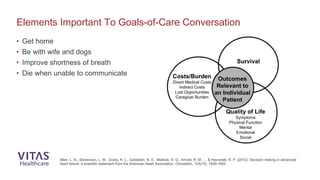

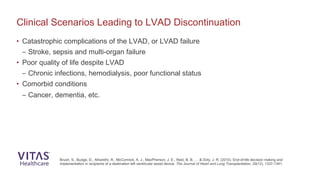

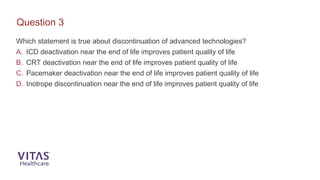

The document outlines continuing education (CE) credit provisions for healthcare professionals involved in hospice care for patients with advanced cardiac disease (ACD) and highlights the significant burden of heart failure on patients, caregivers, and healthcare systems. It discusses hospice eligibility guidelines, emphasizing the importance of patient symptoms over objective measures like ejection fraction, and includes statistics on the prevalence of heart disease and its associated costs. Additionally, it illustrates how hospice care can help reduce hospital readmissions and improve the quality of life for heart failure patients.