The document discusses binary search trees (BST) as a crucial data structure for dynamic sets, covering their properties, basic operations, and methods for insertion, deletion, and traversal. It explains how to perform various operations such as searching for minimum and maximum values, determining successors and predecessors, and using both recursive and iterative approaches for tree searches. Additionally, the document addresses sorting using BSTs and compares their performance to quicksort.

![L12.11

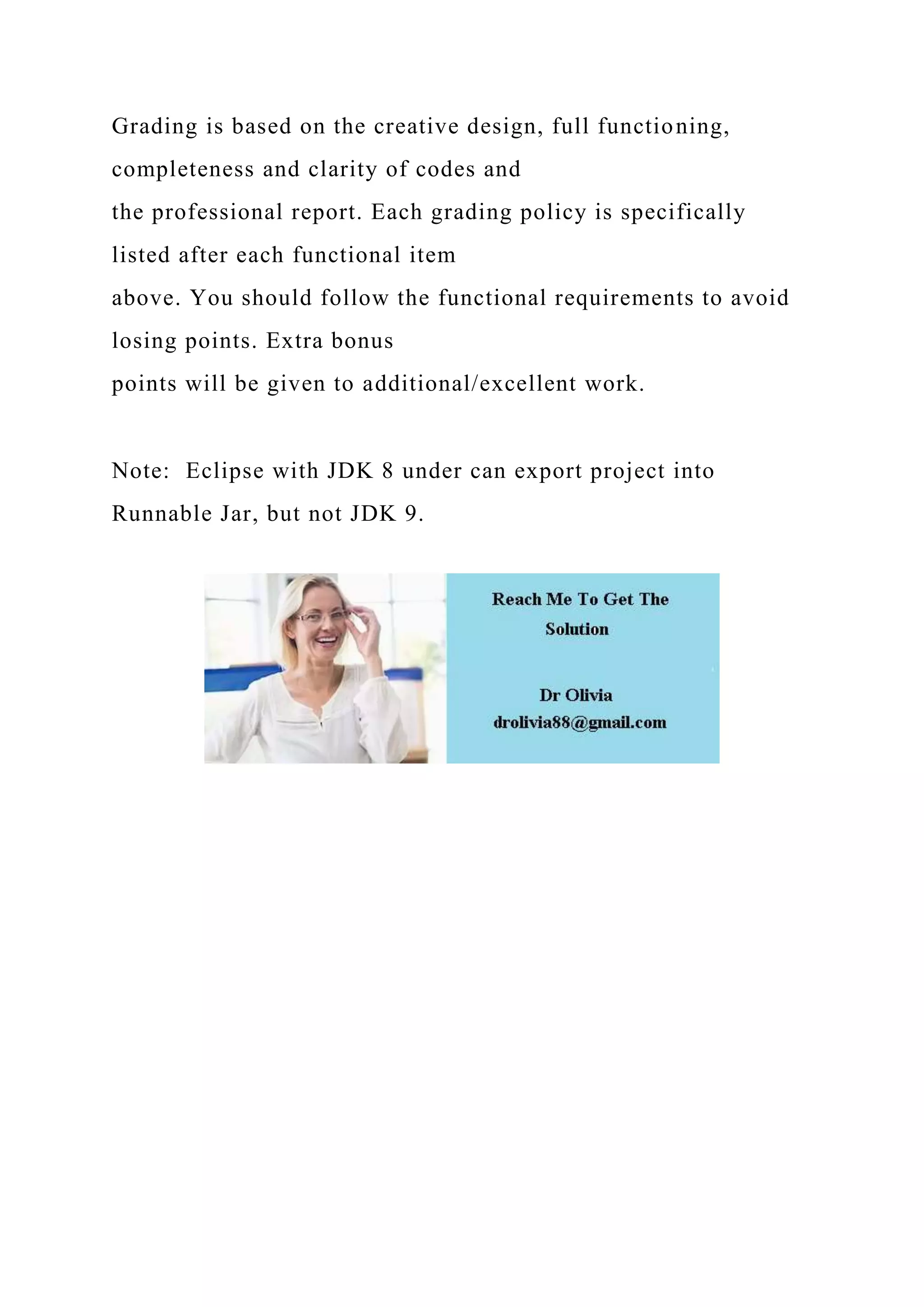

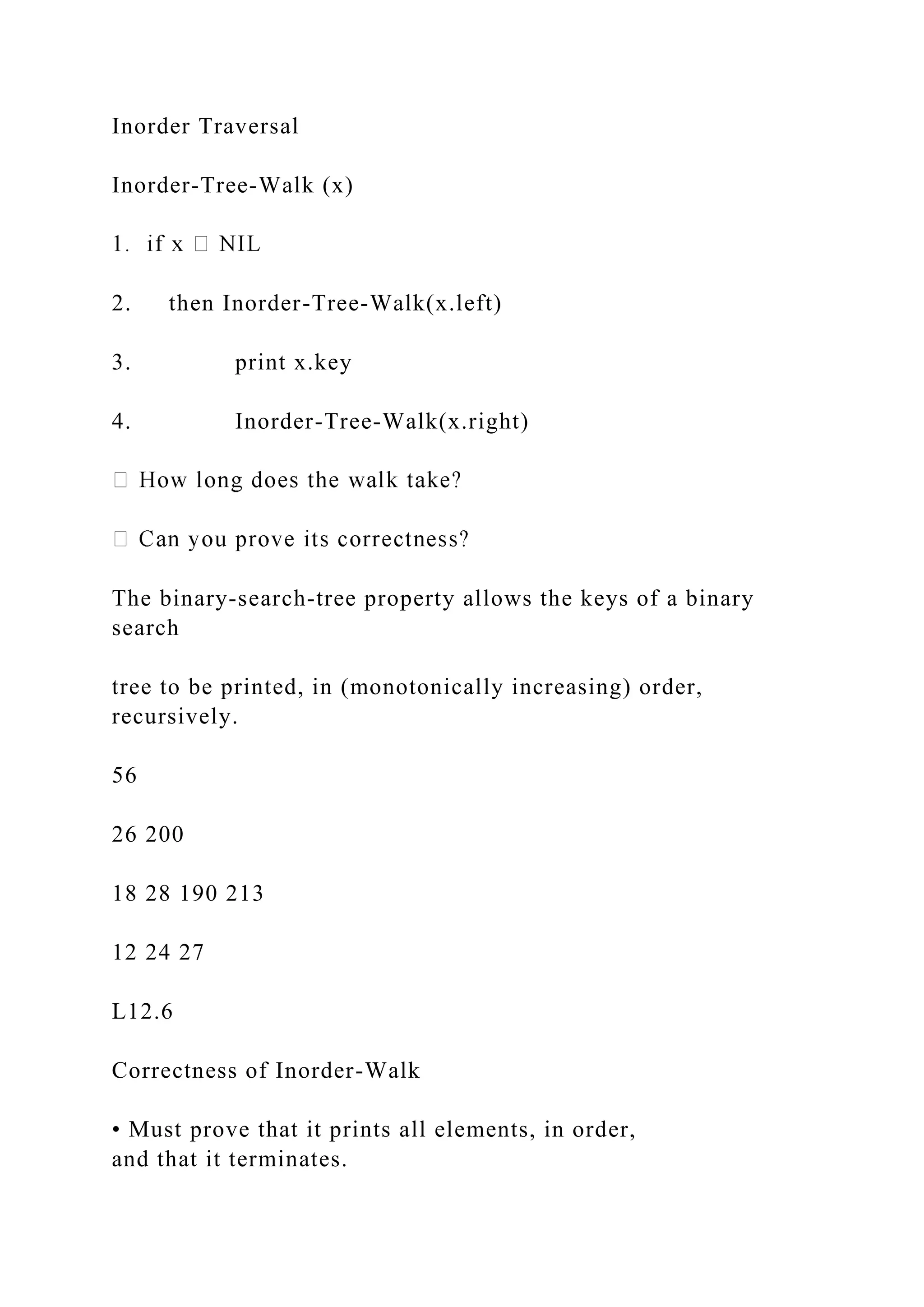

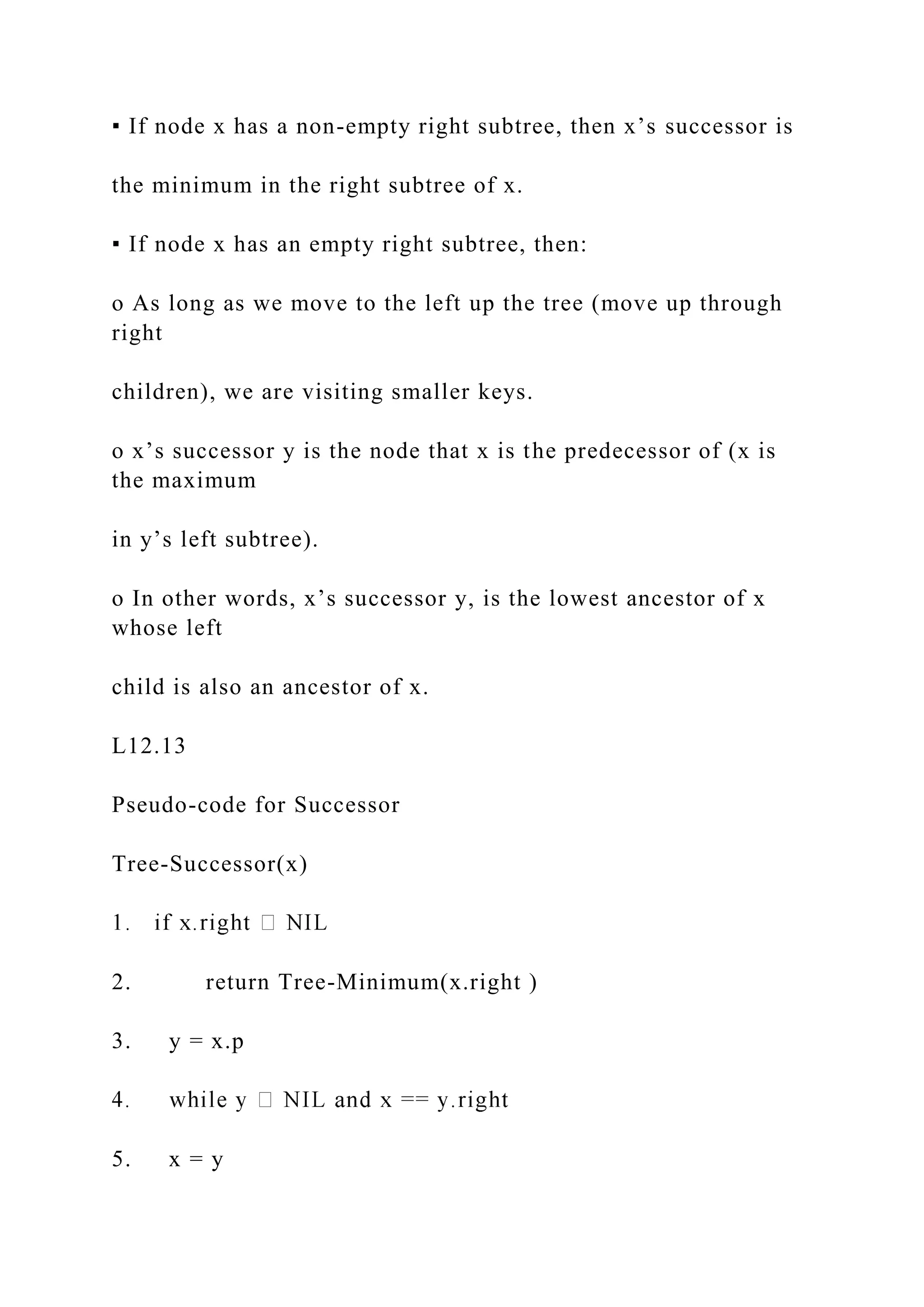

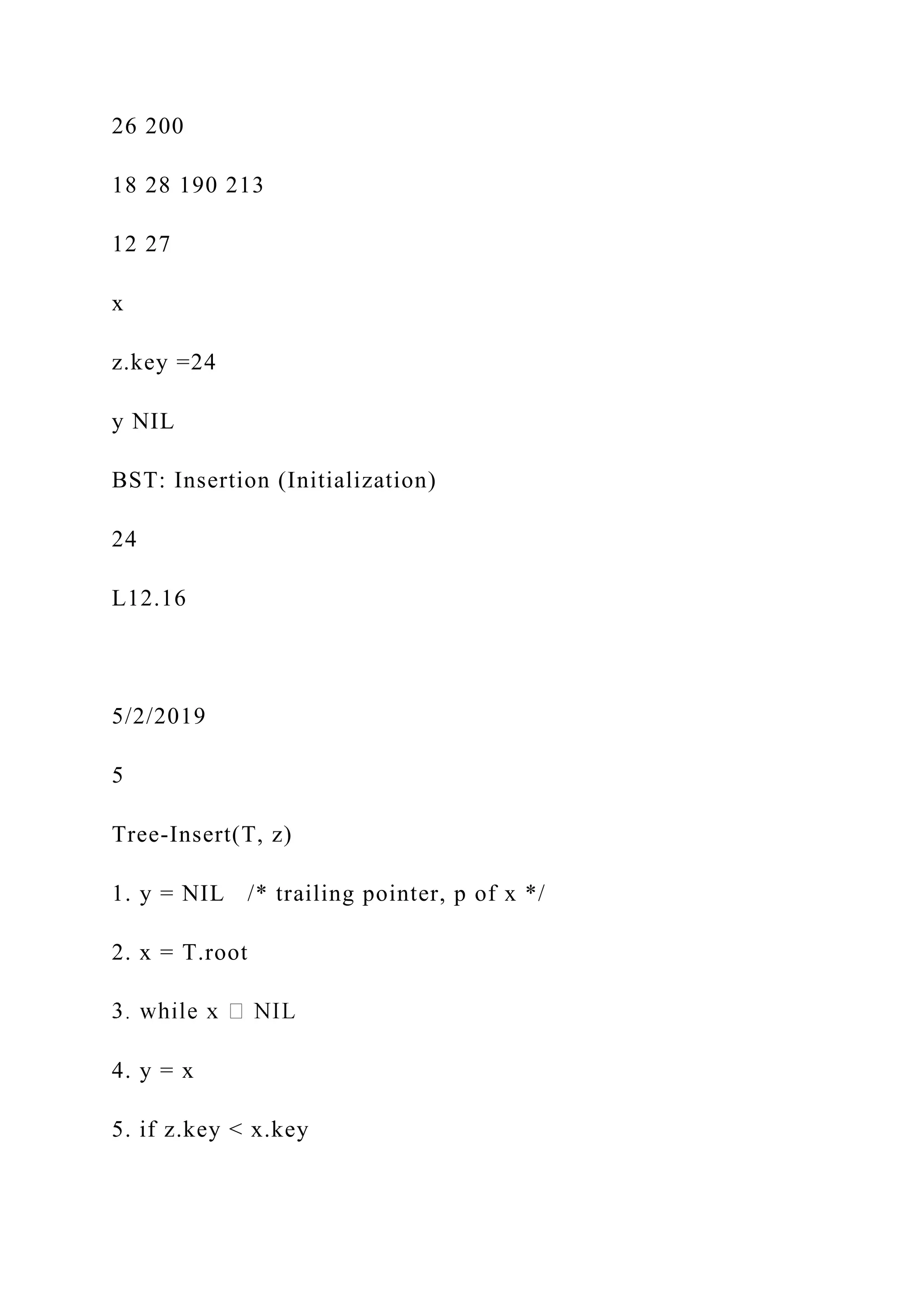

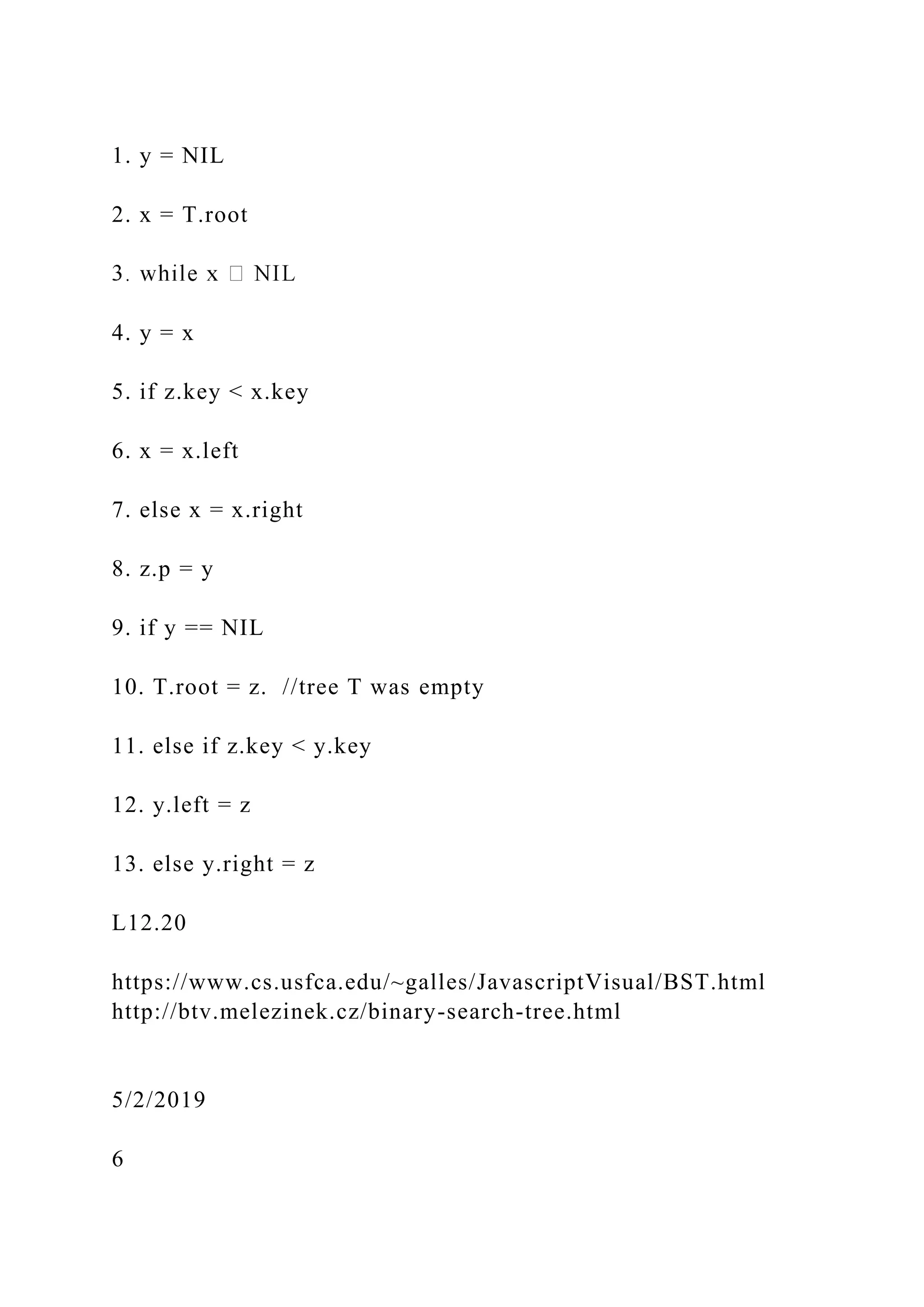

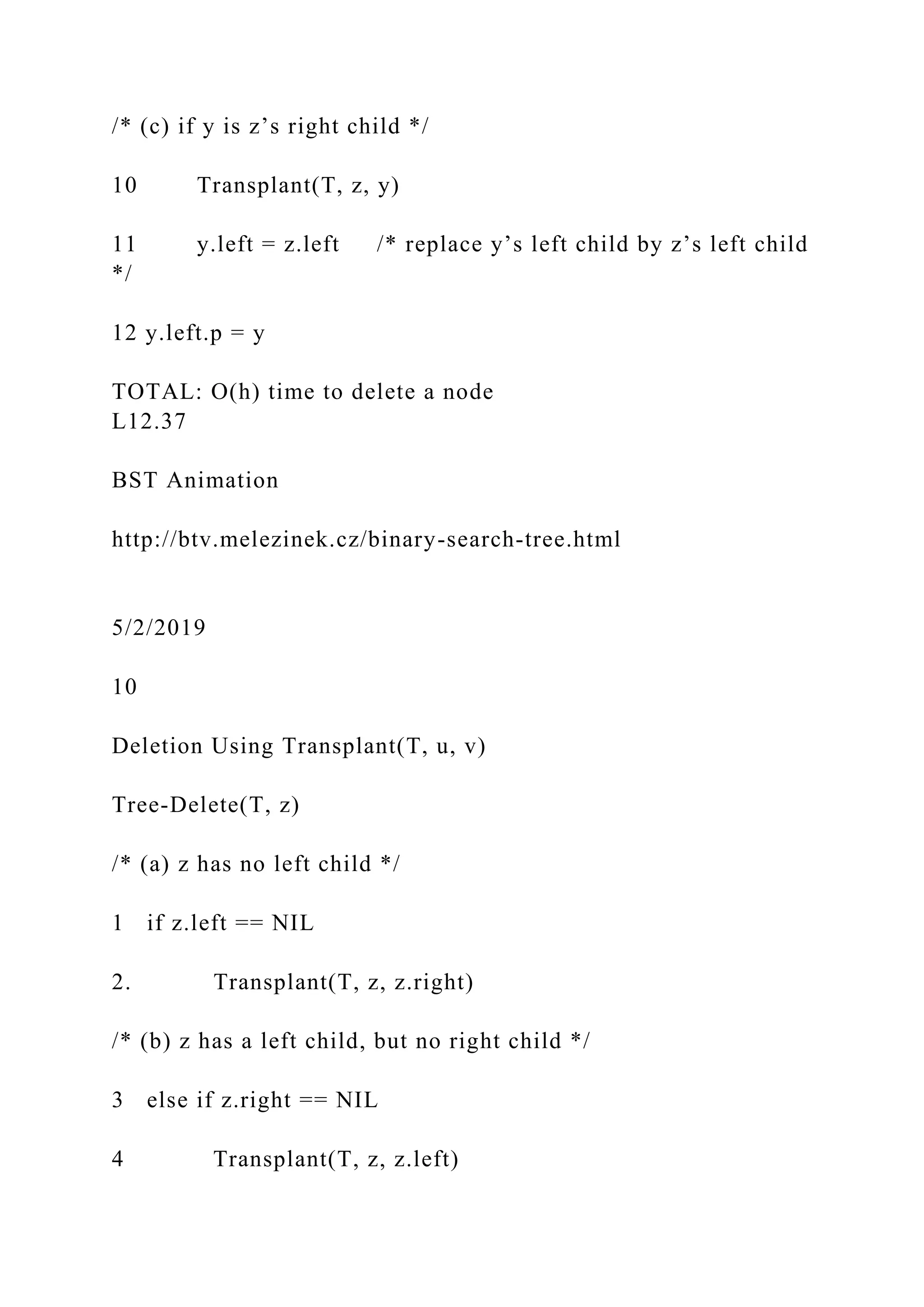

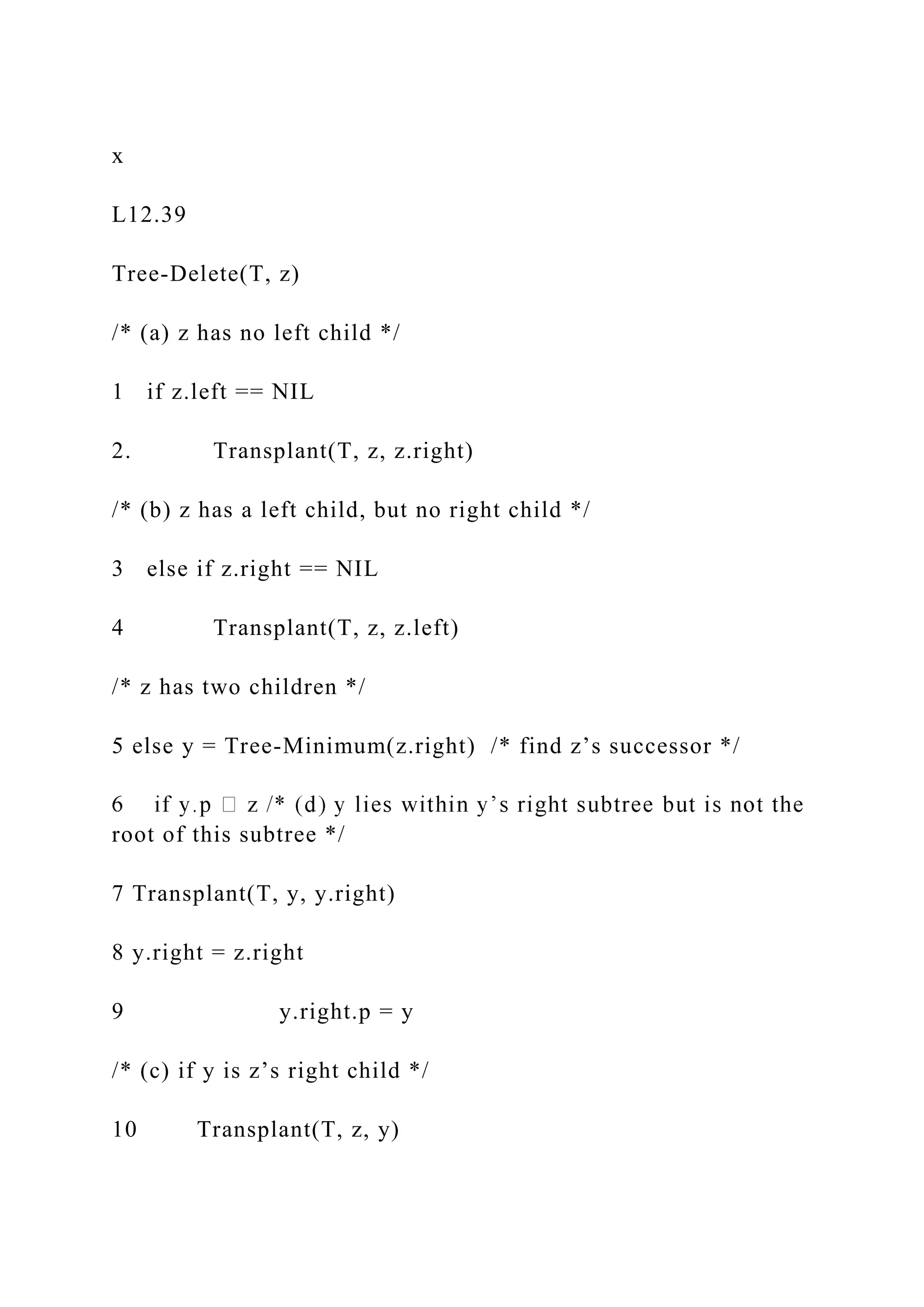

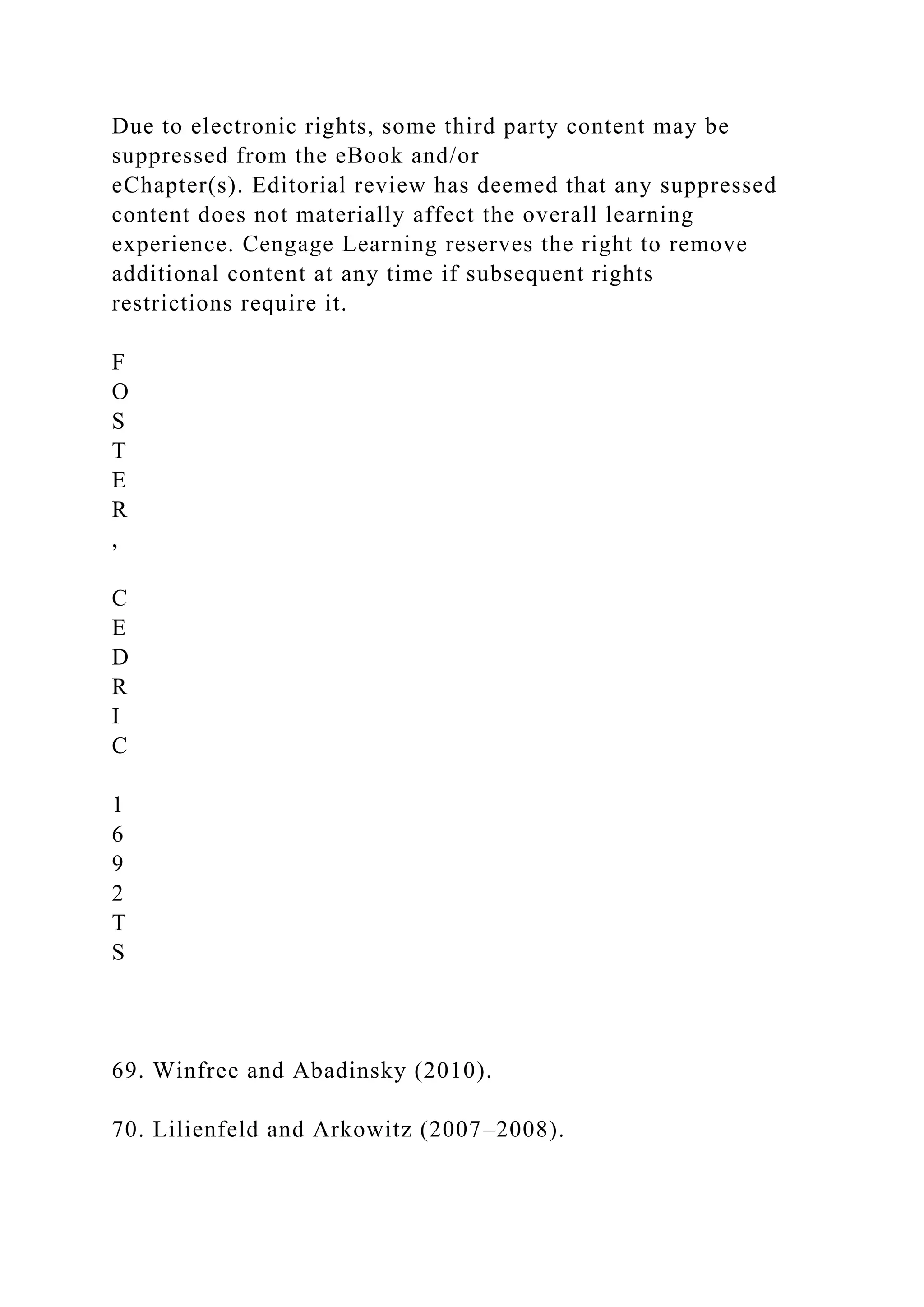

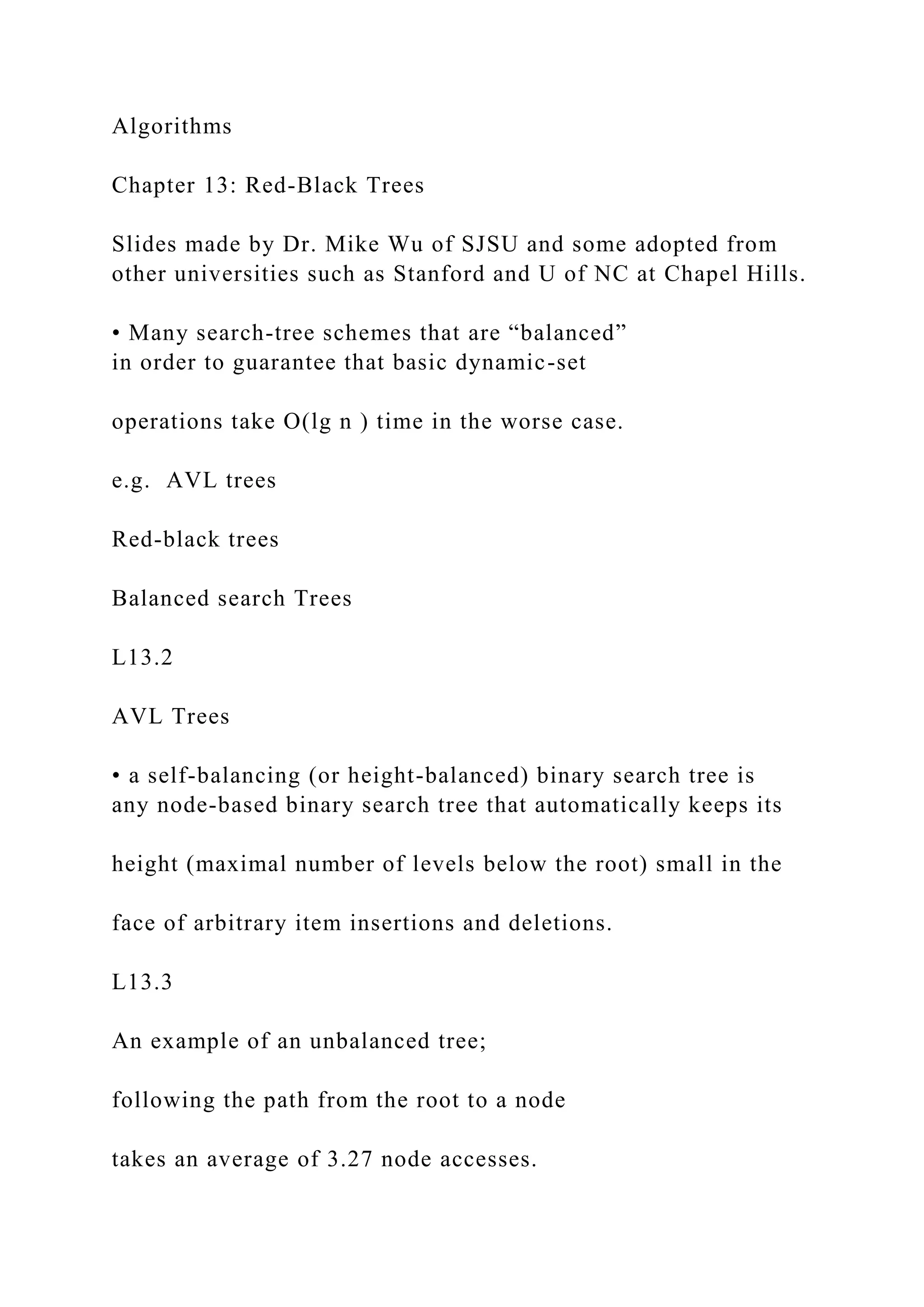

How to finding Min & Max

Tree-Minimum(x) Tree-Maximum(x)

2. x = x.left 2. x = x.right

3. return x 3. return x

Q: How long do they take?

-search-tree property guarantees that:

» The minimum is located at the left-most node.

» The maximum is located at the right-most node.

L12.12

5/2/2019

4

Successor and Predecessor

• Successor of node x is the node y such that key[y] is the

smallest key greater than key[x].

• The successor of the largest key is NIL.

• Search consists of two cases.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-8-2048.jpg)

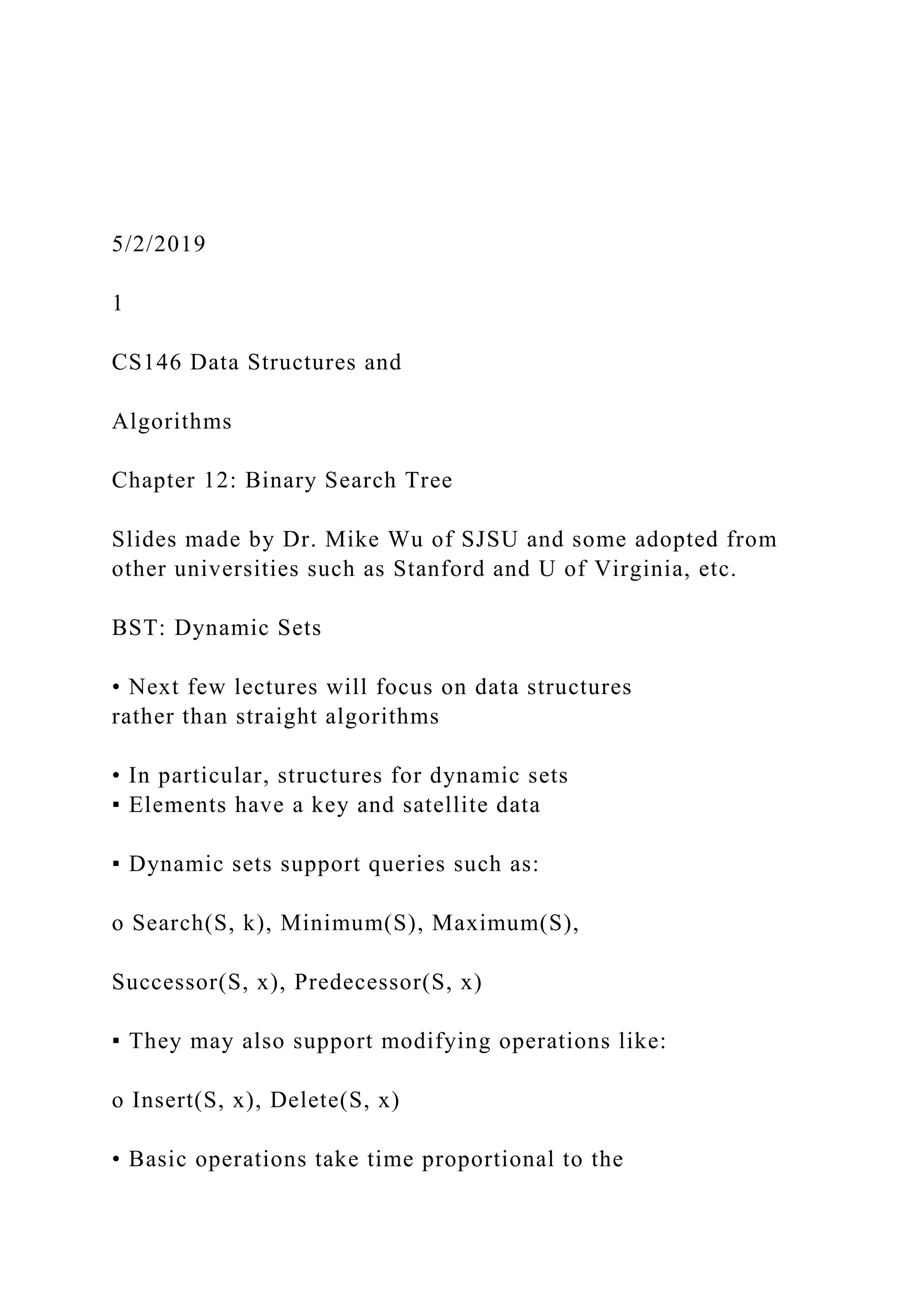

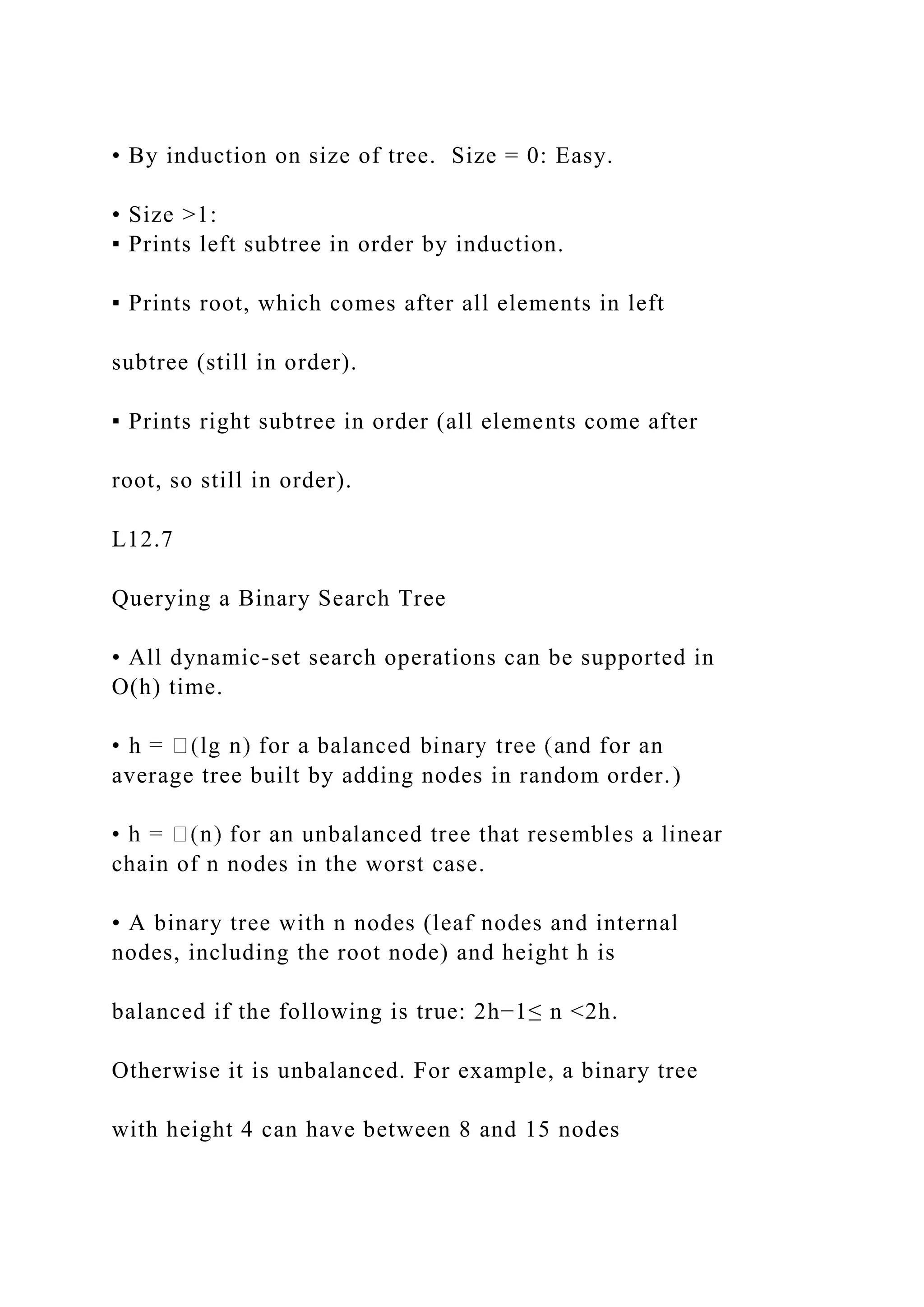

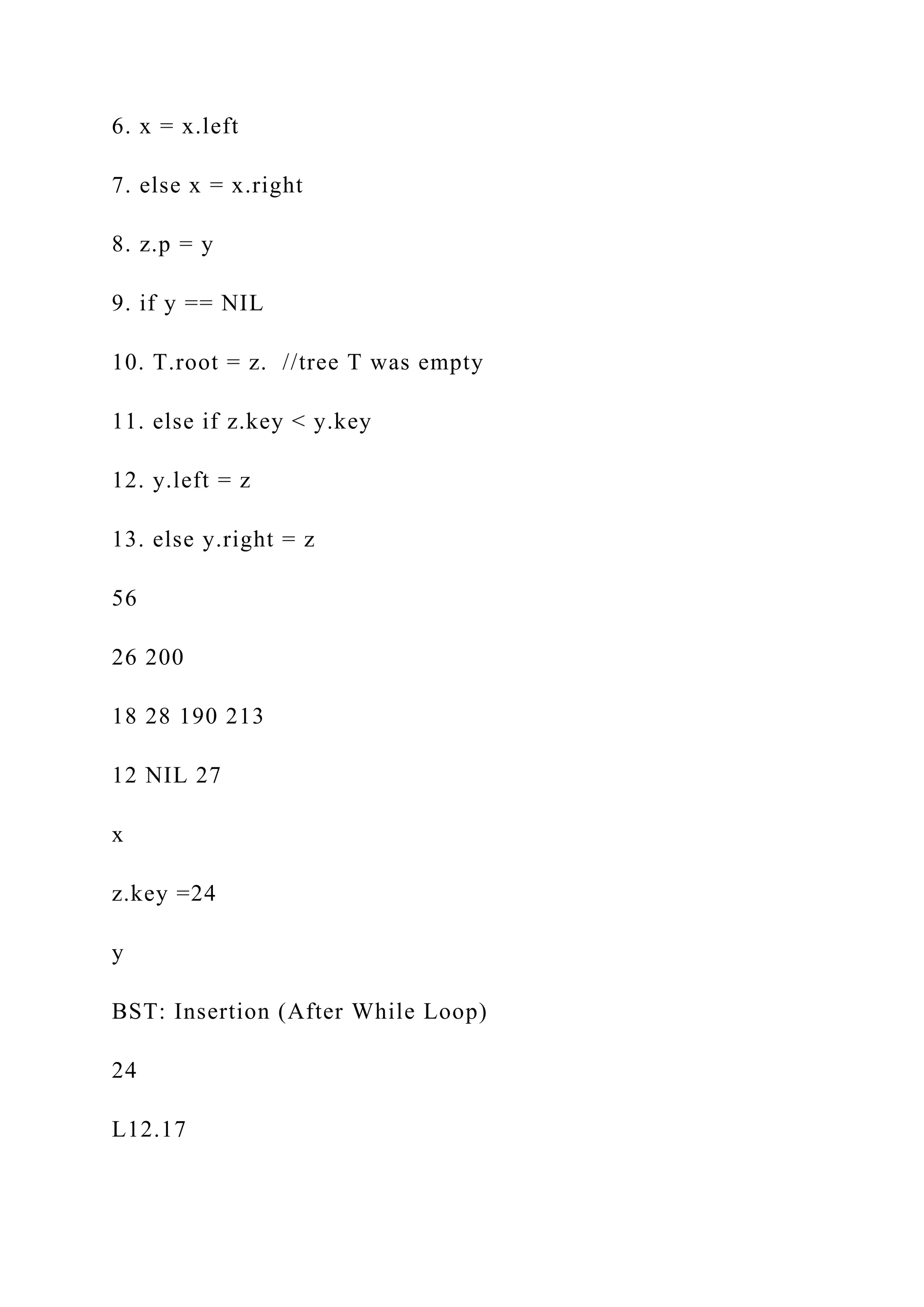

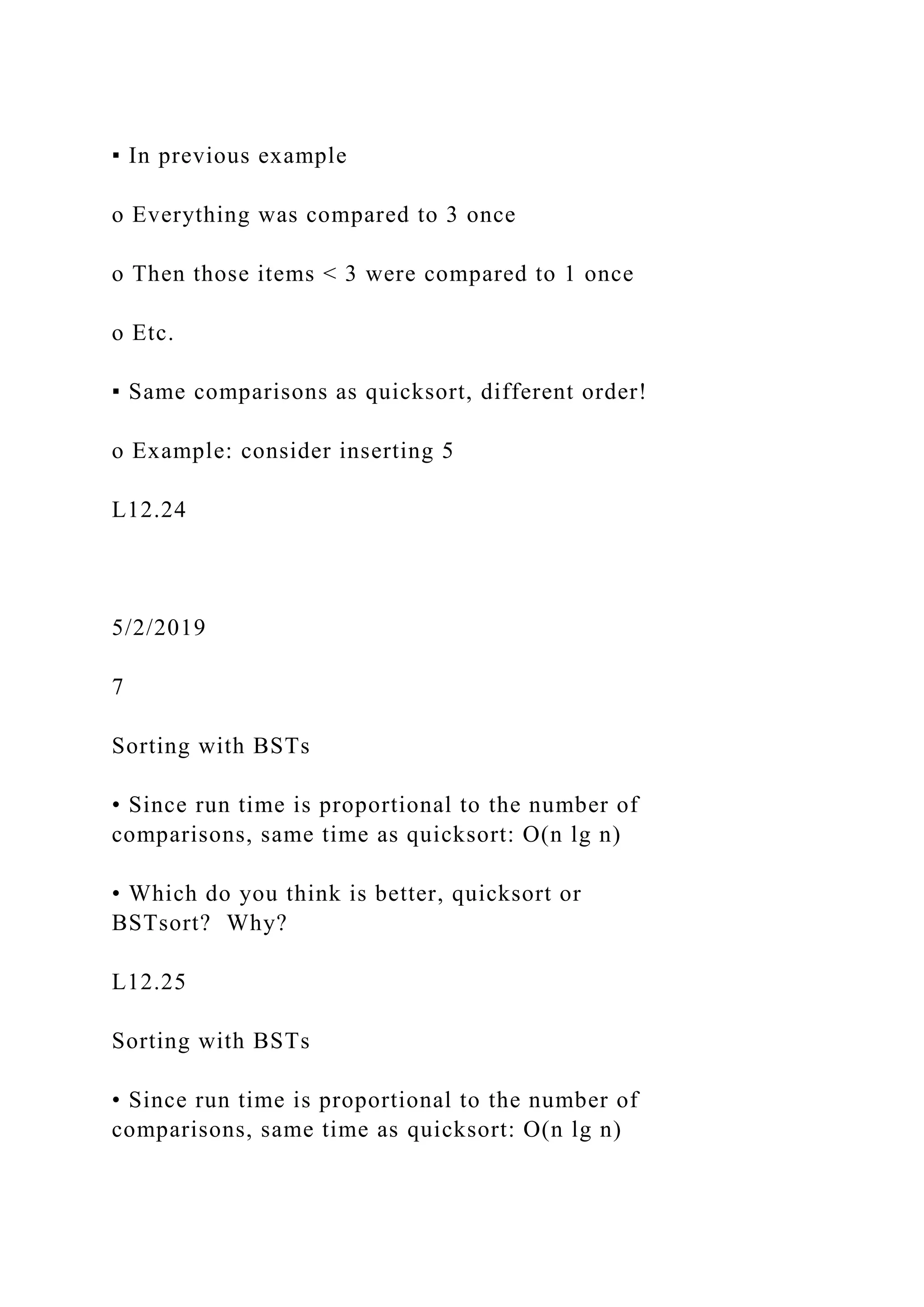

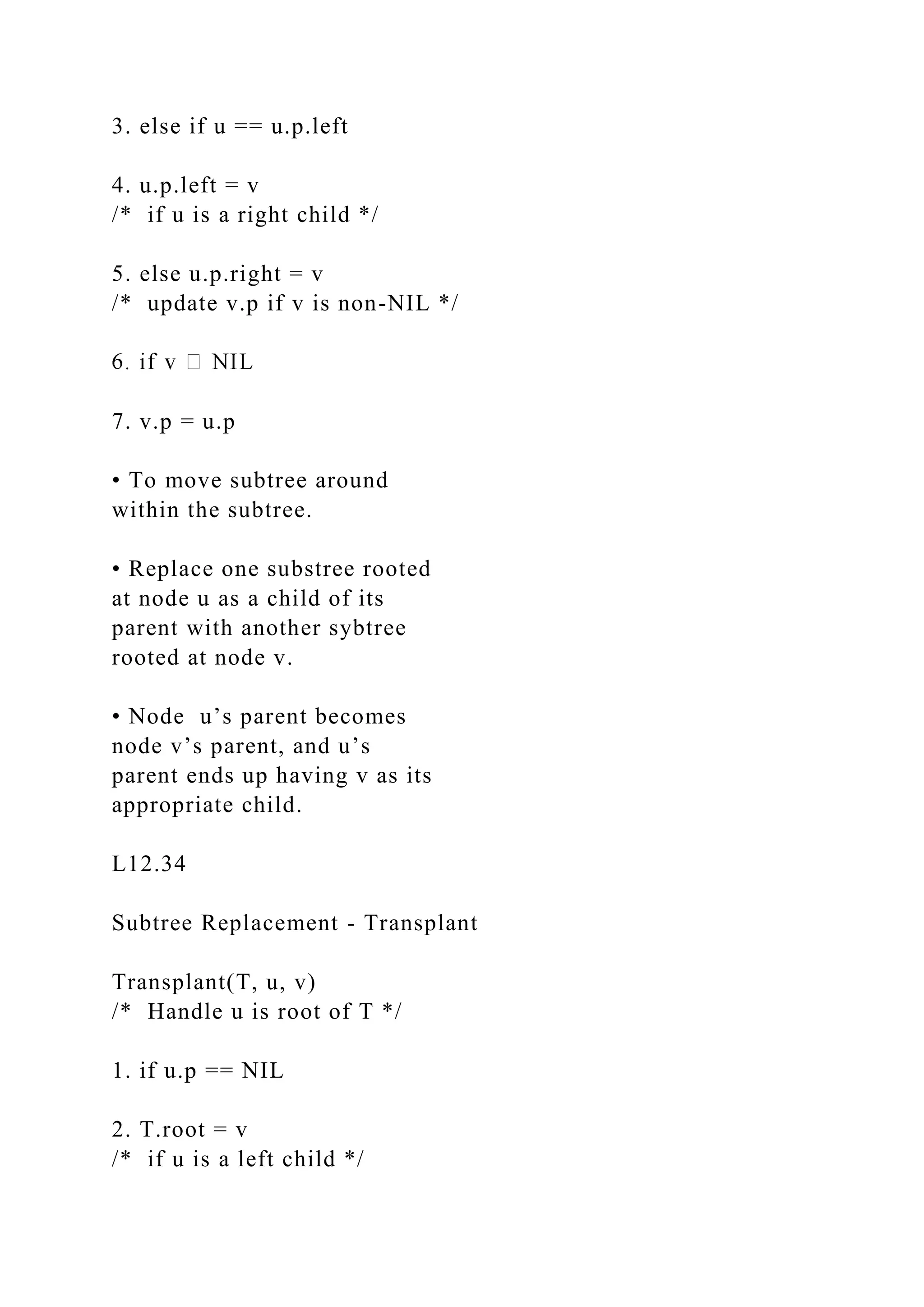

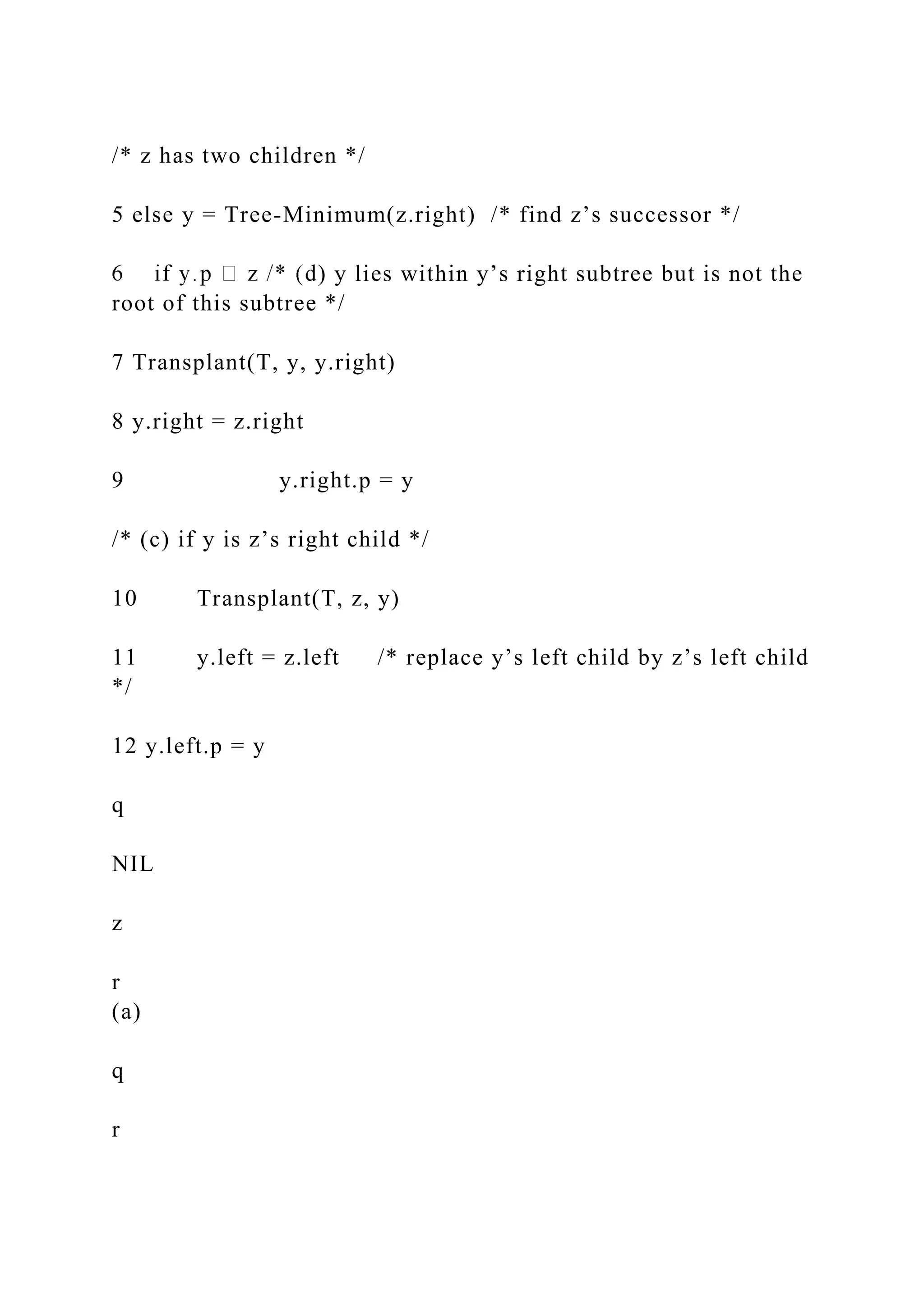

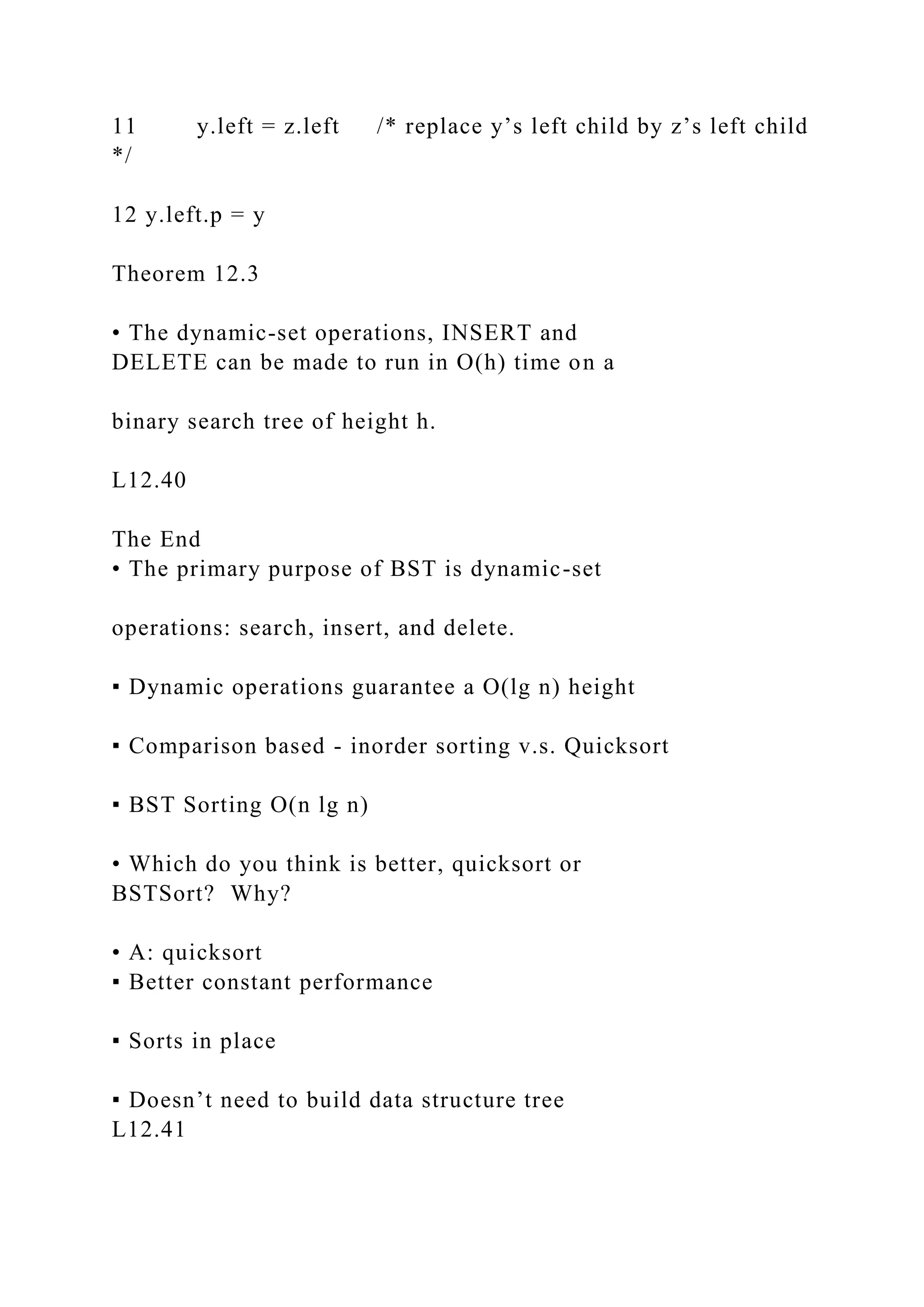

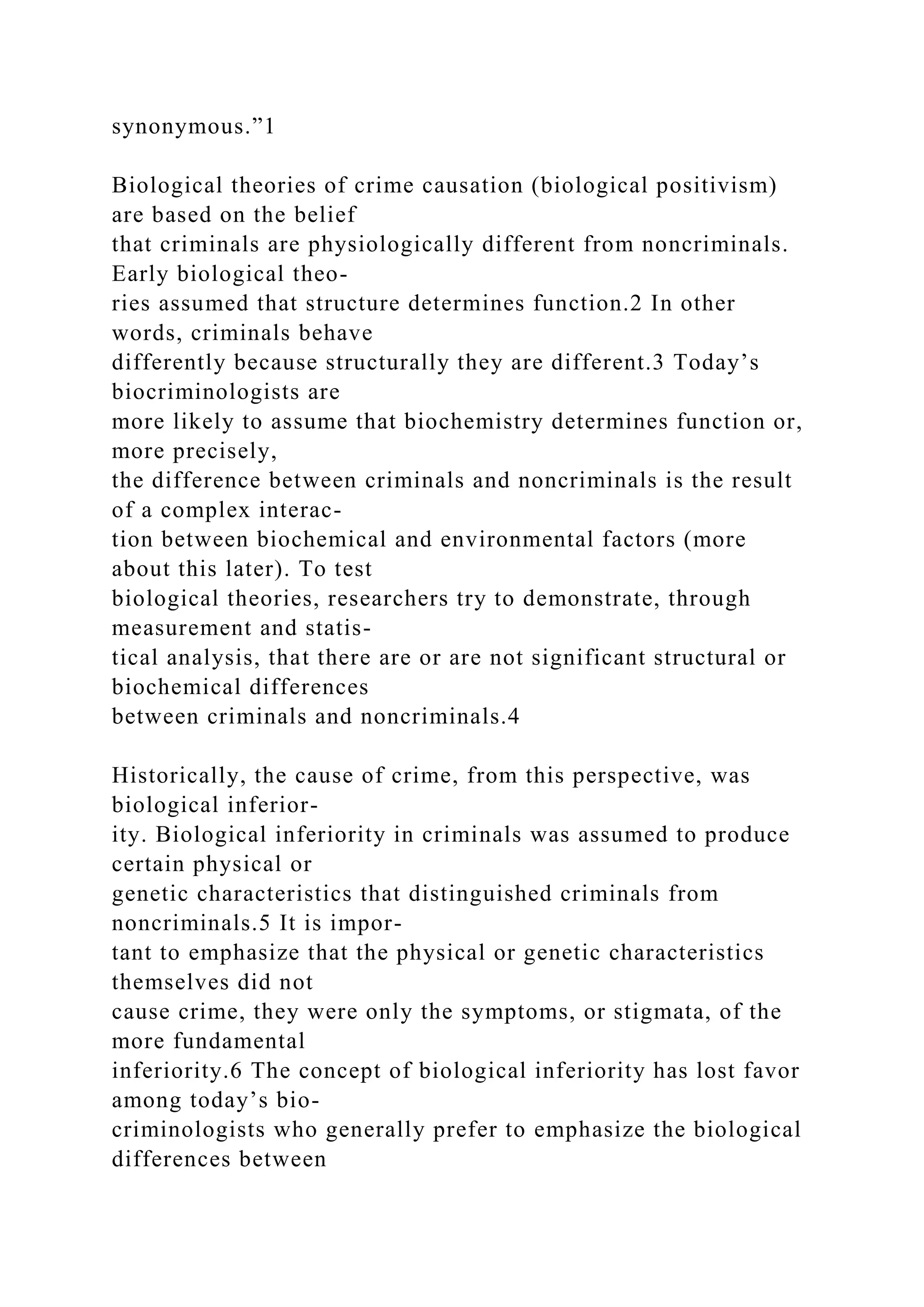

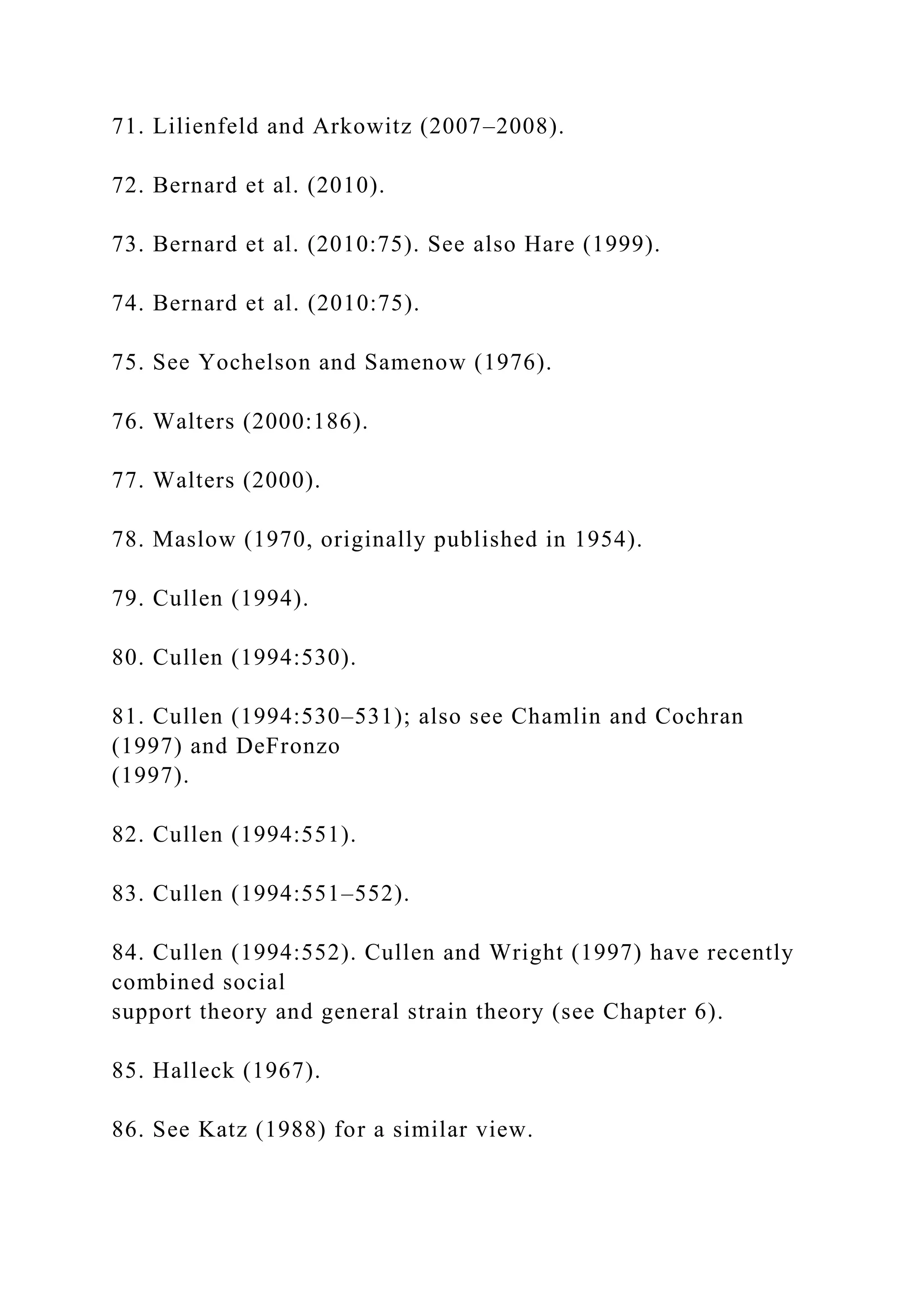

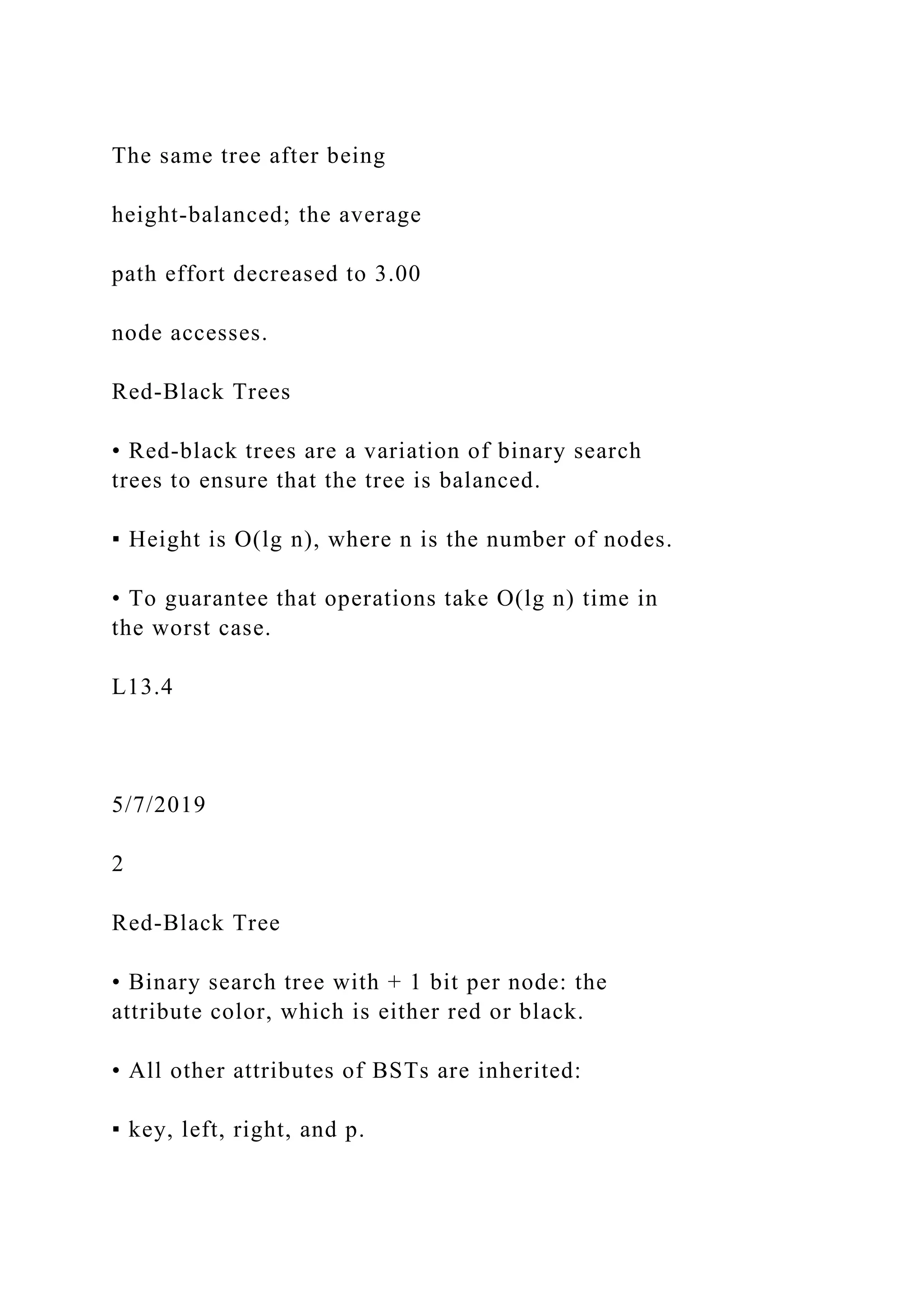

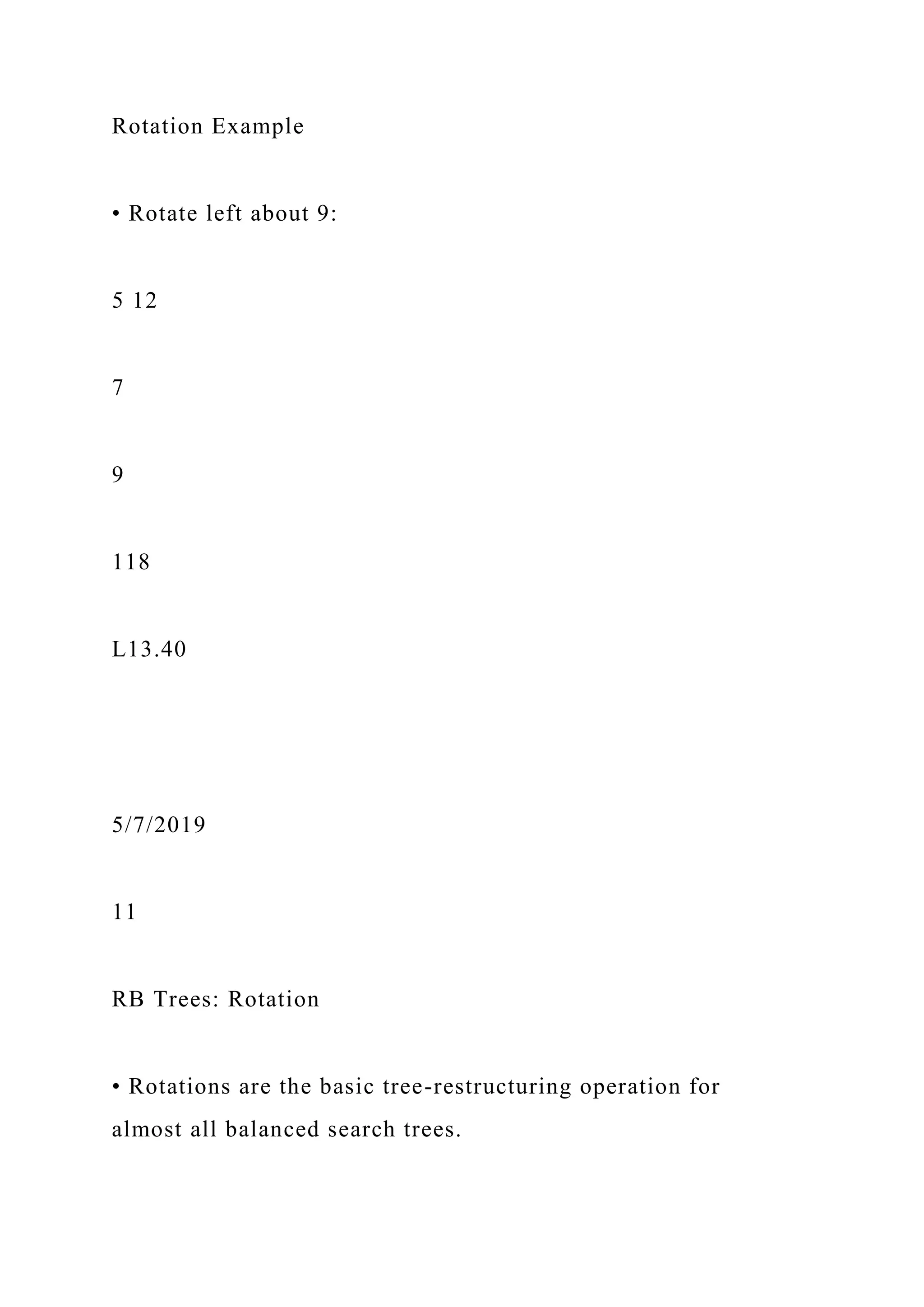

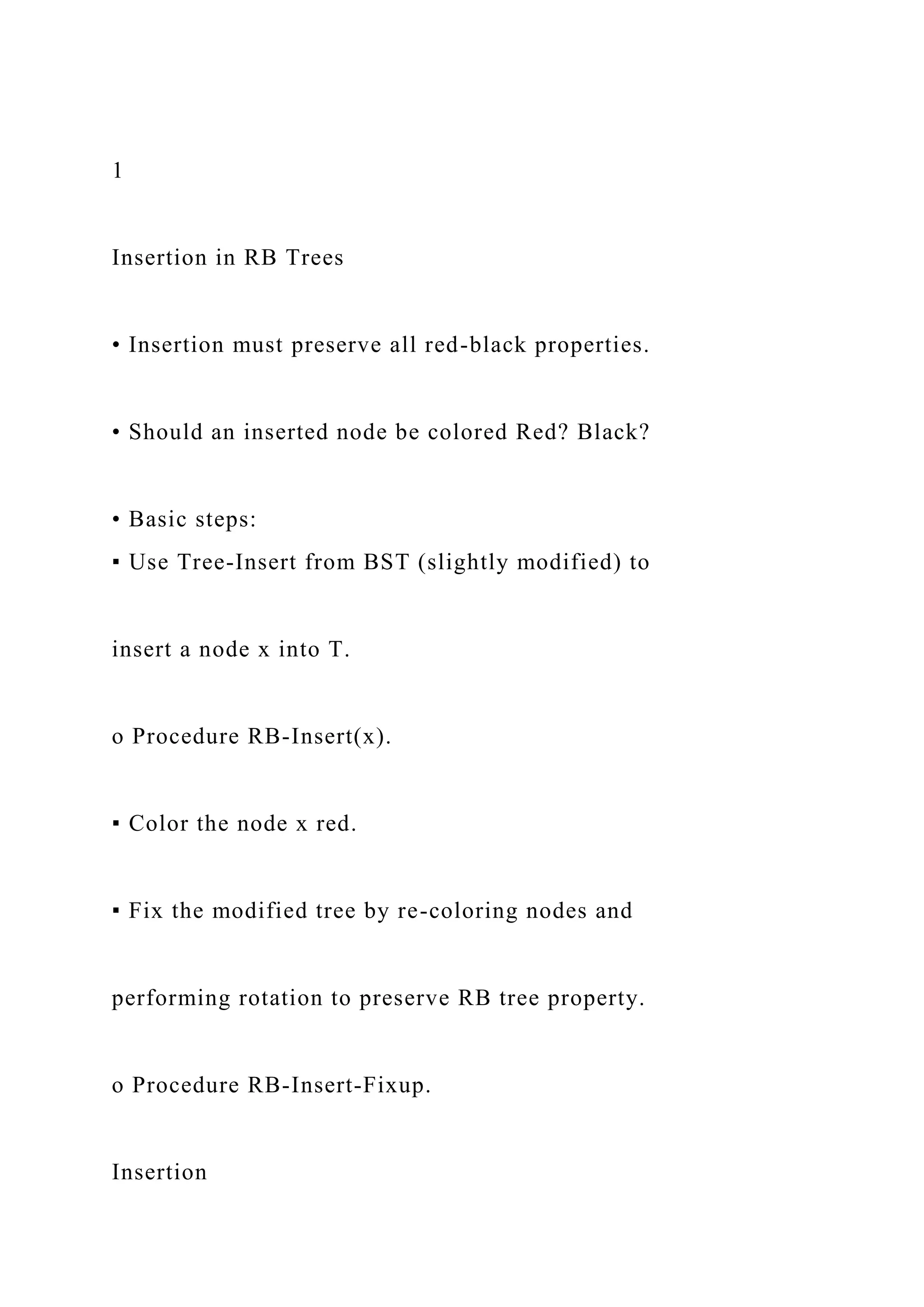

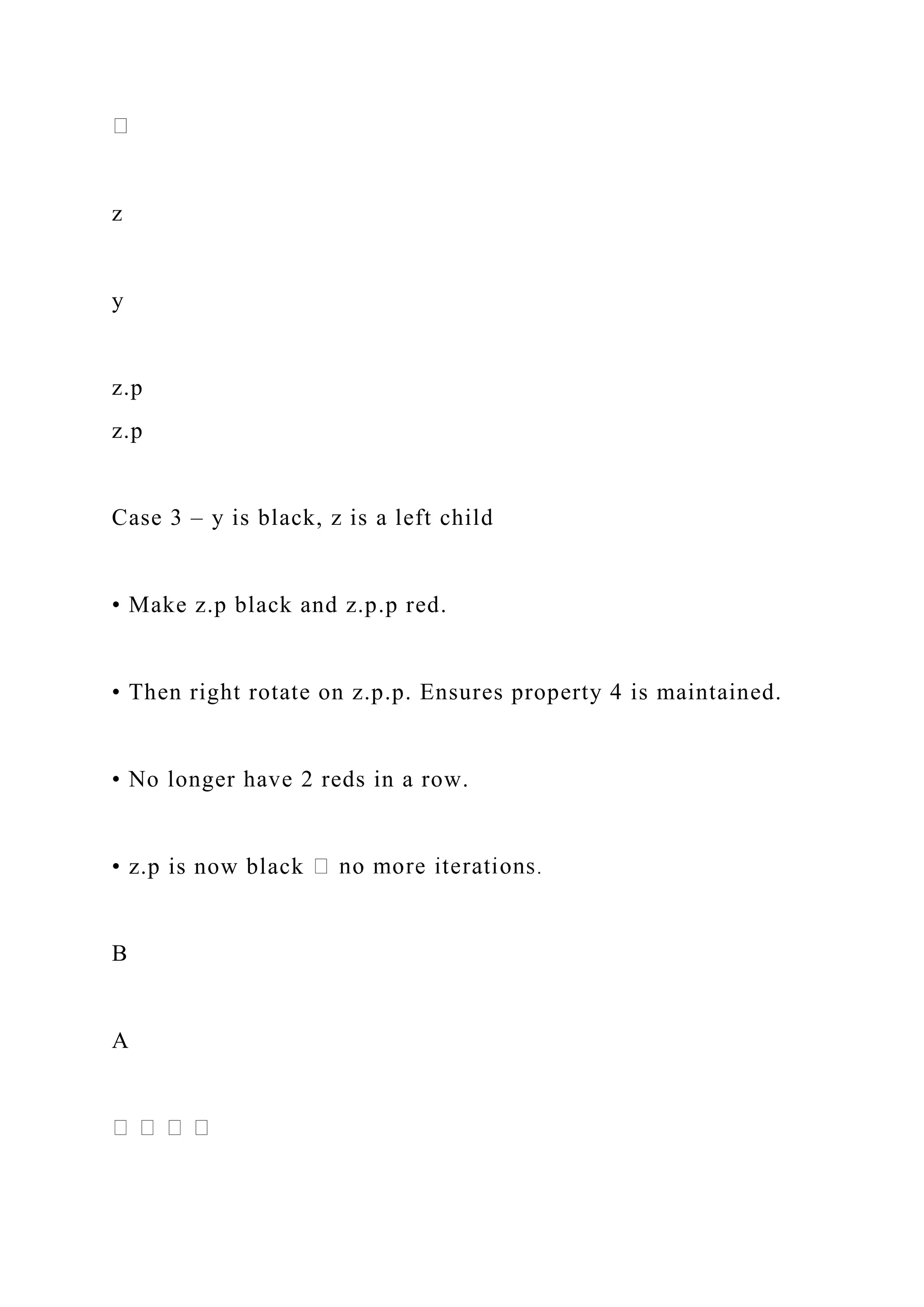

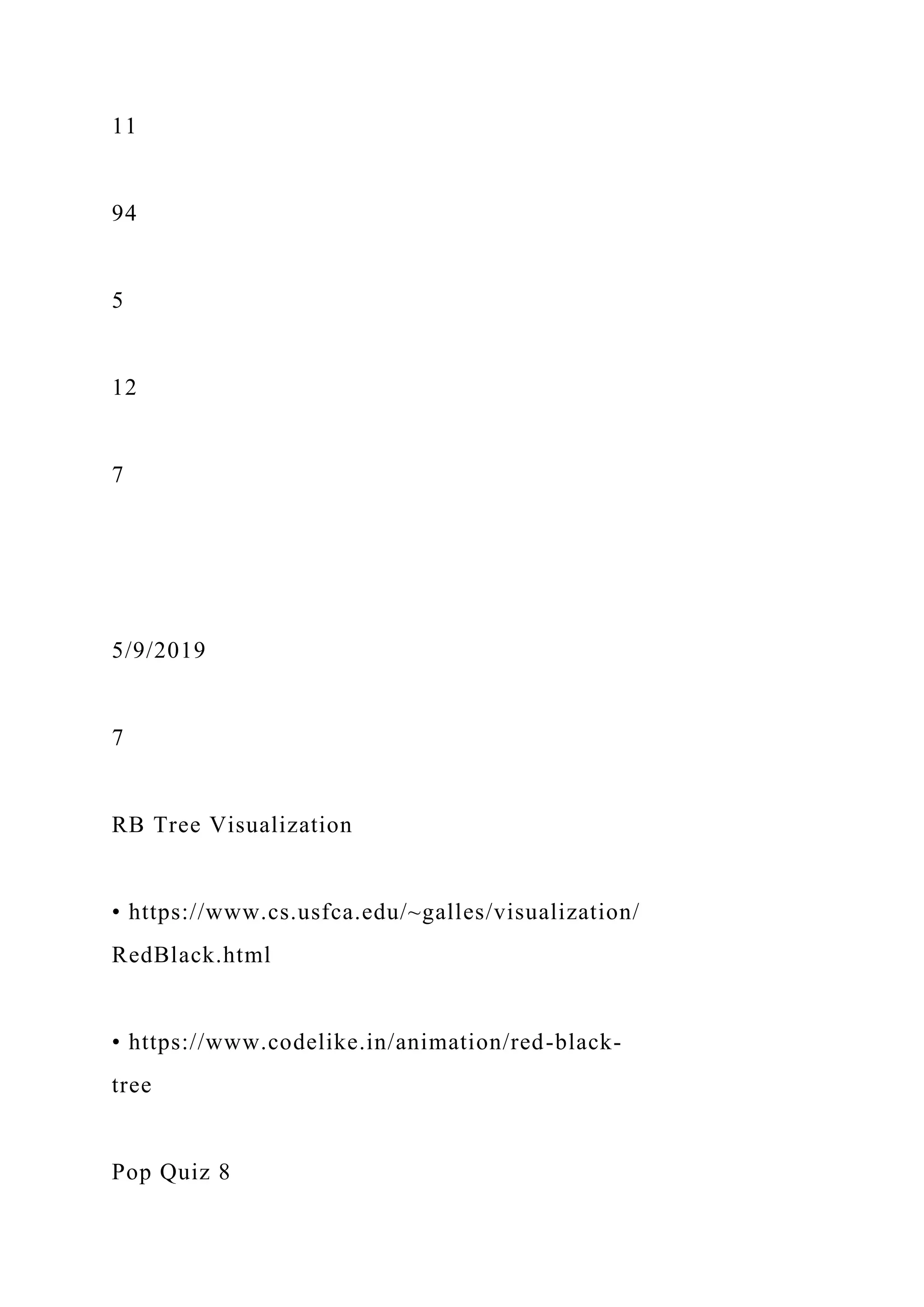

![Exercise: Sorting Using BSTs

BSTSort (A)

to n

do Tree-Insert(A[i])

Inorder-Tree-Walk(root)

▪ What are the worst case and best case running

times?

▪ In practice, how would this compare to other

sorting algorithms?

L12.21

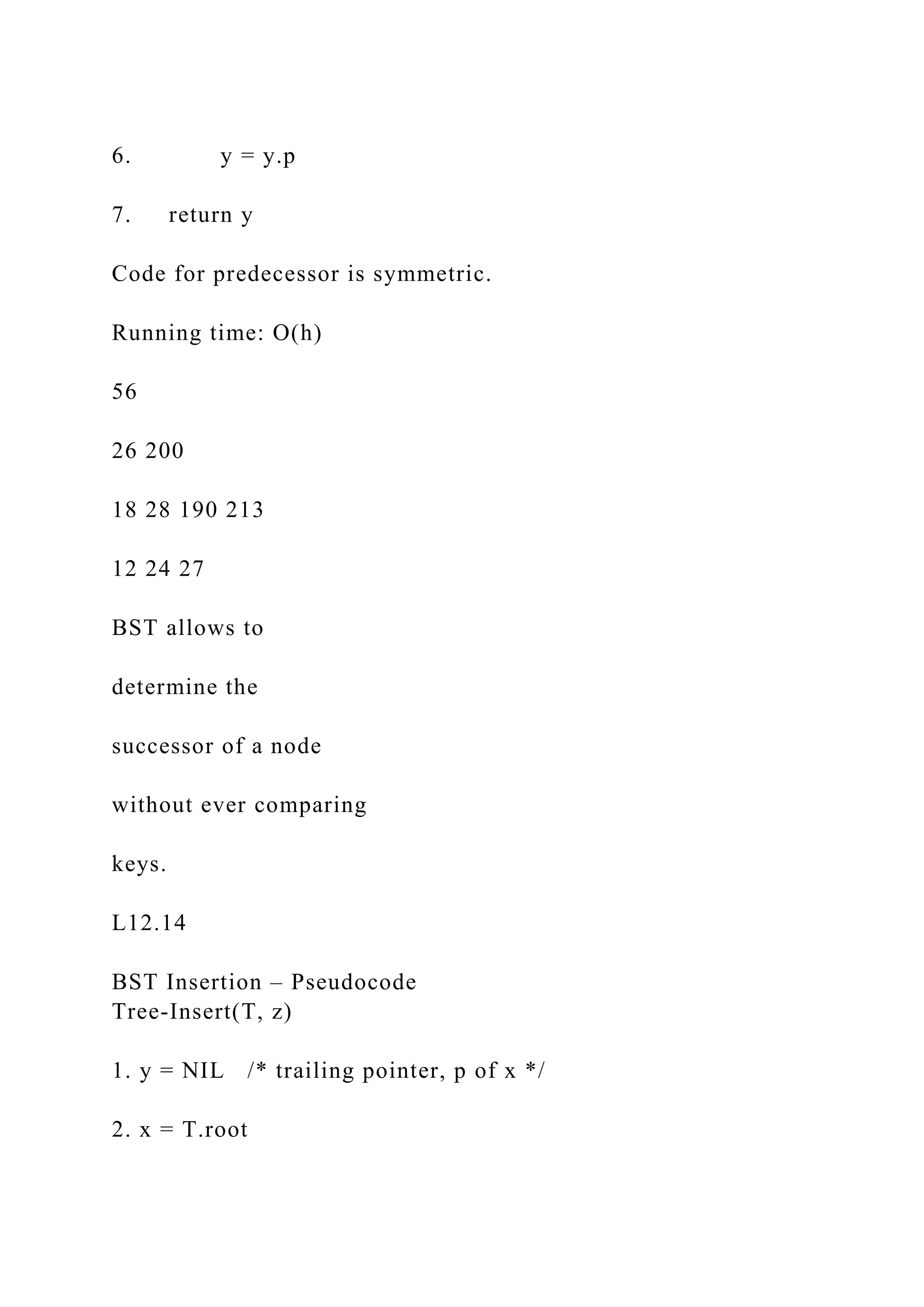

Sorting With Binary Search Trees

• Informal code for sorting array A of length n:

BSTSort(A)

for i=1 to n

TreeInsert(A[i]);

InorderTreeWalk(root);

• What will be the running time in the

▪ Worst case?

▪ Average case? (hint: remind you of anything?)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-18-2048.jpg)

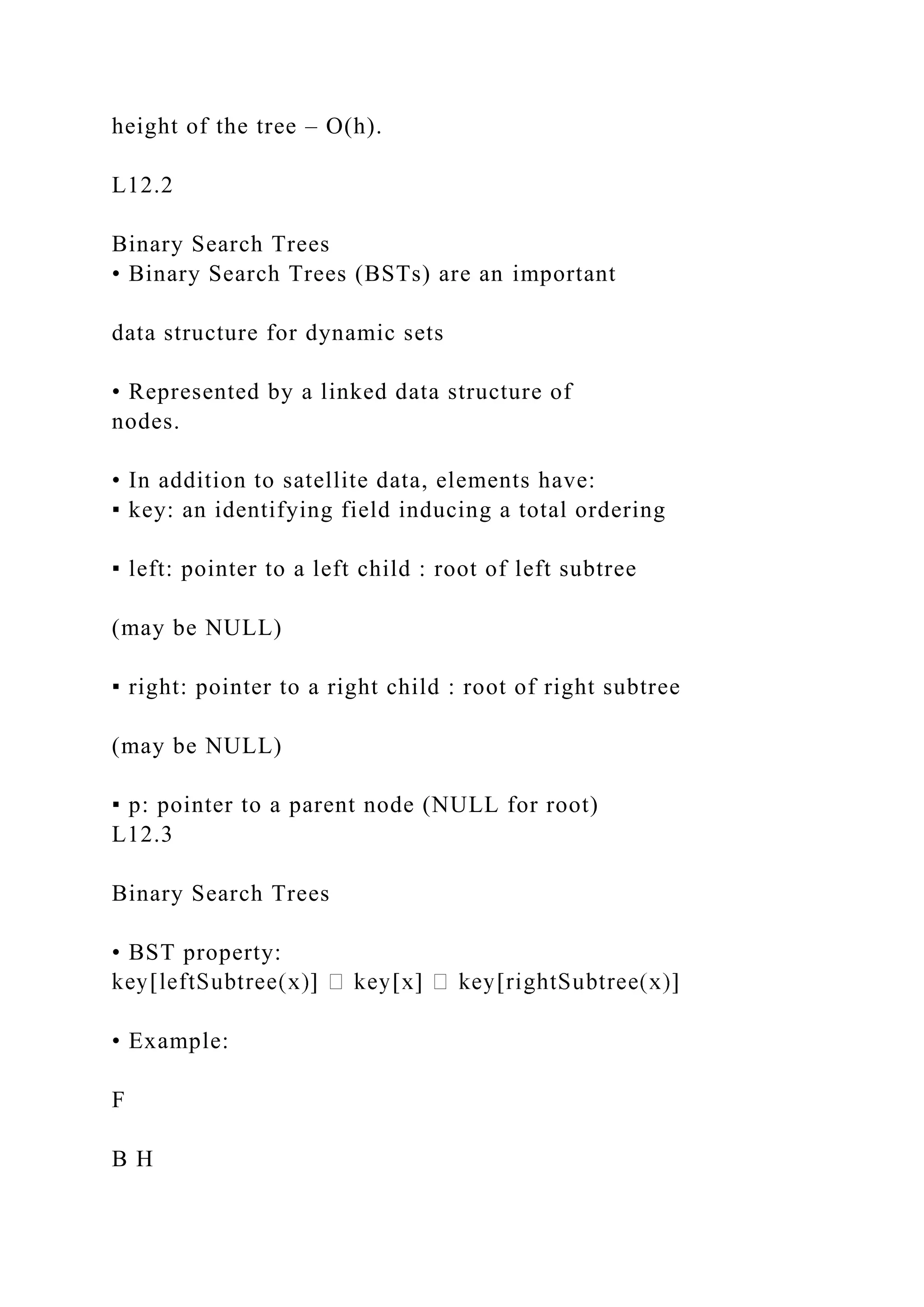

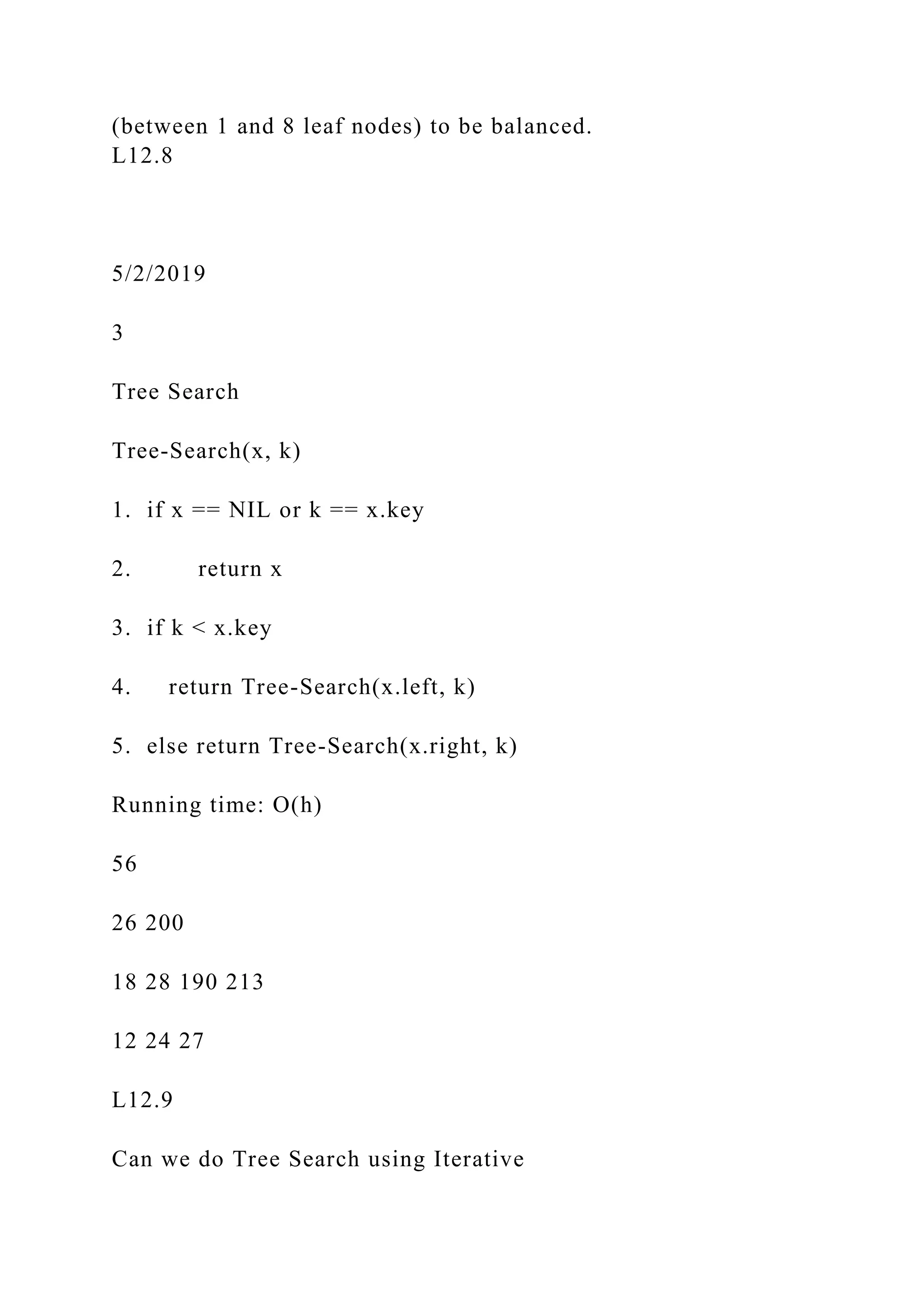

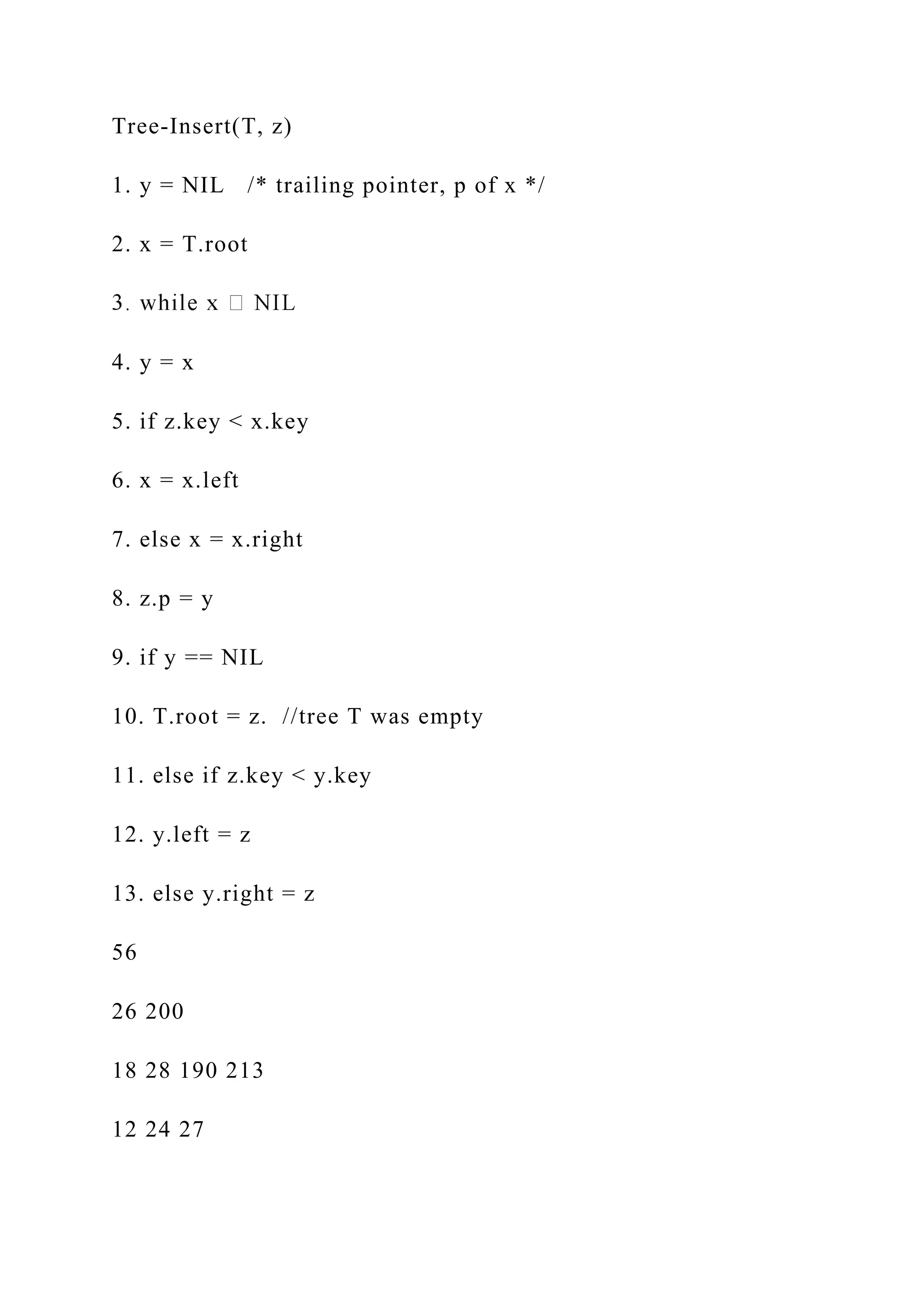

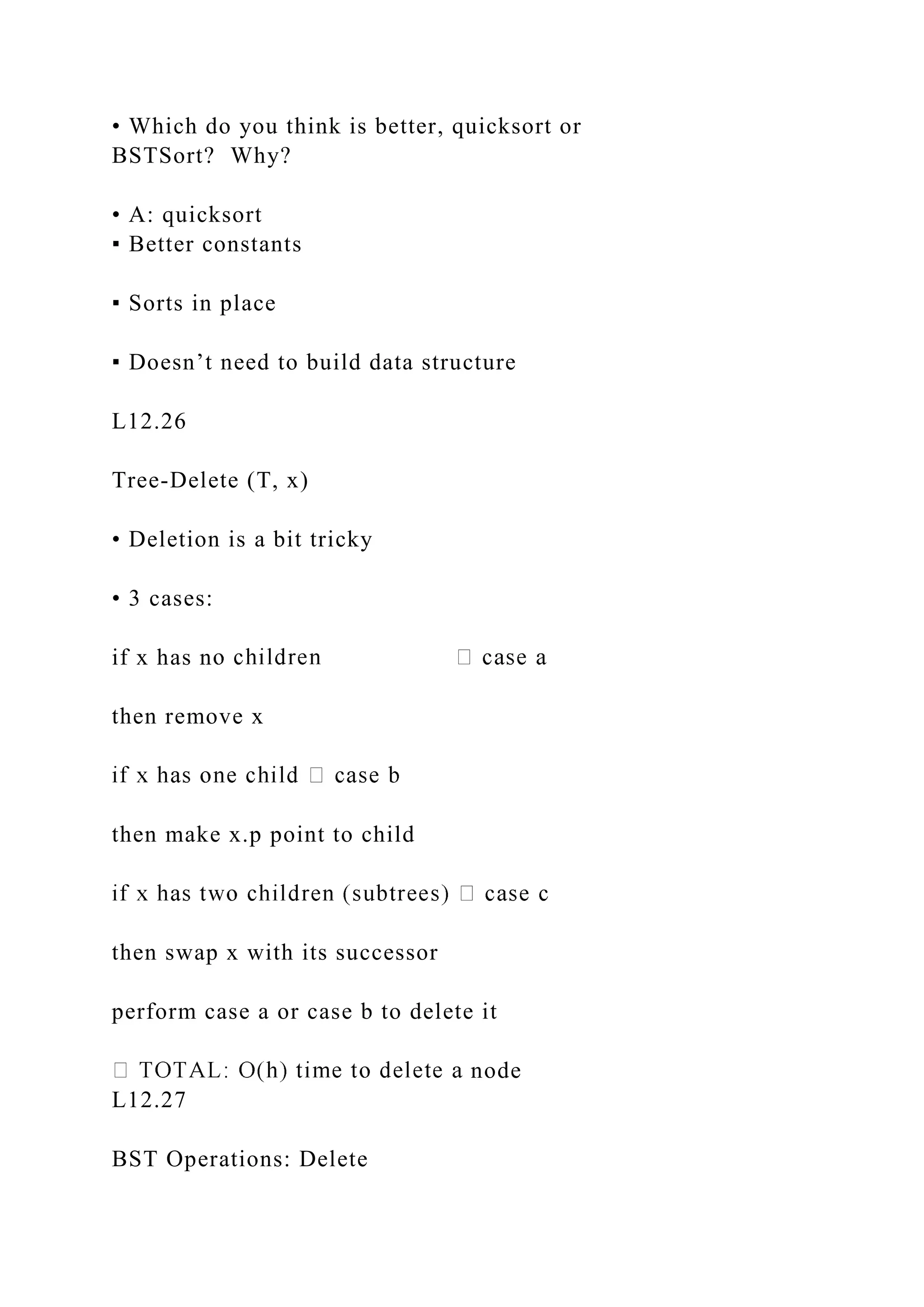

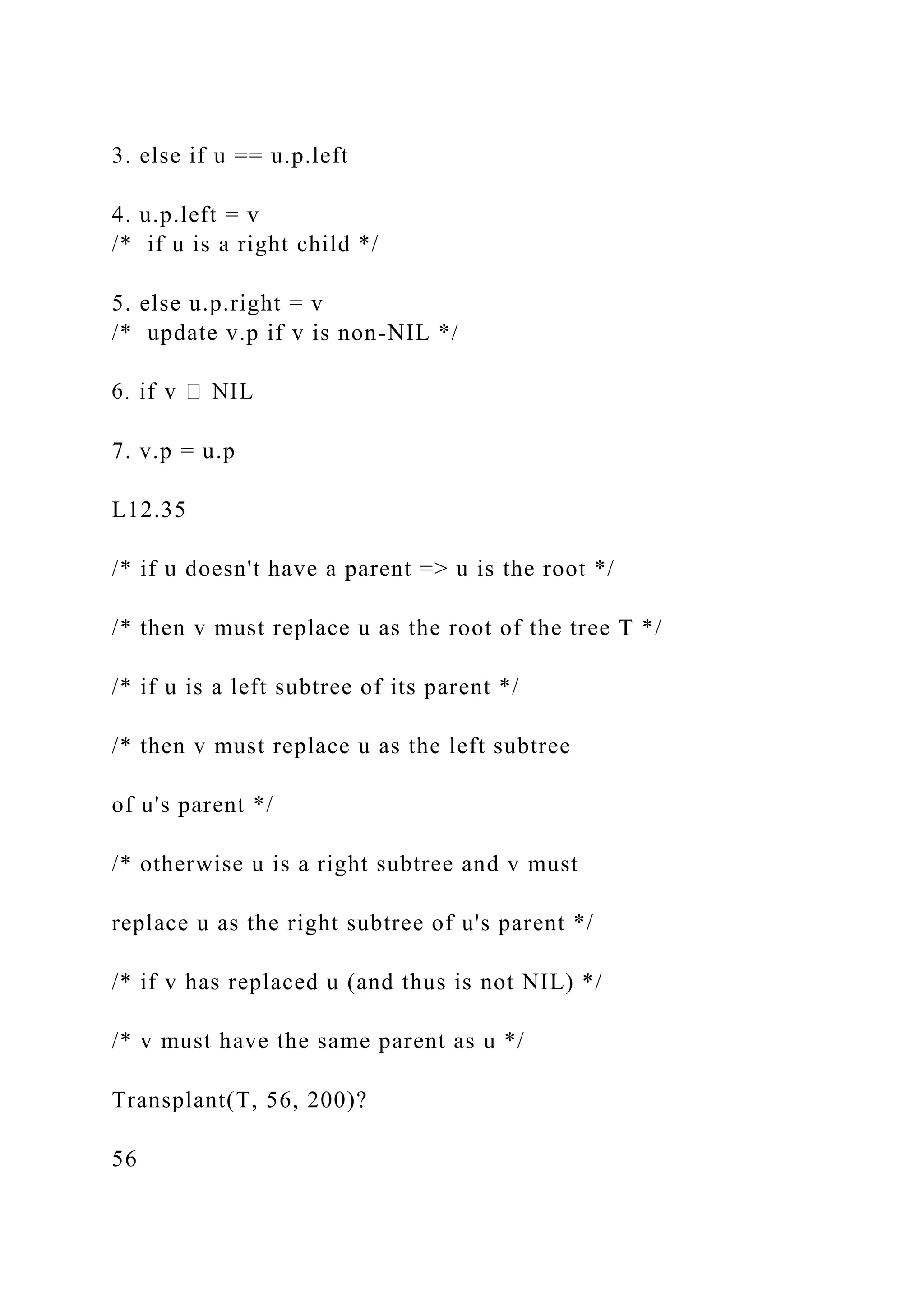

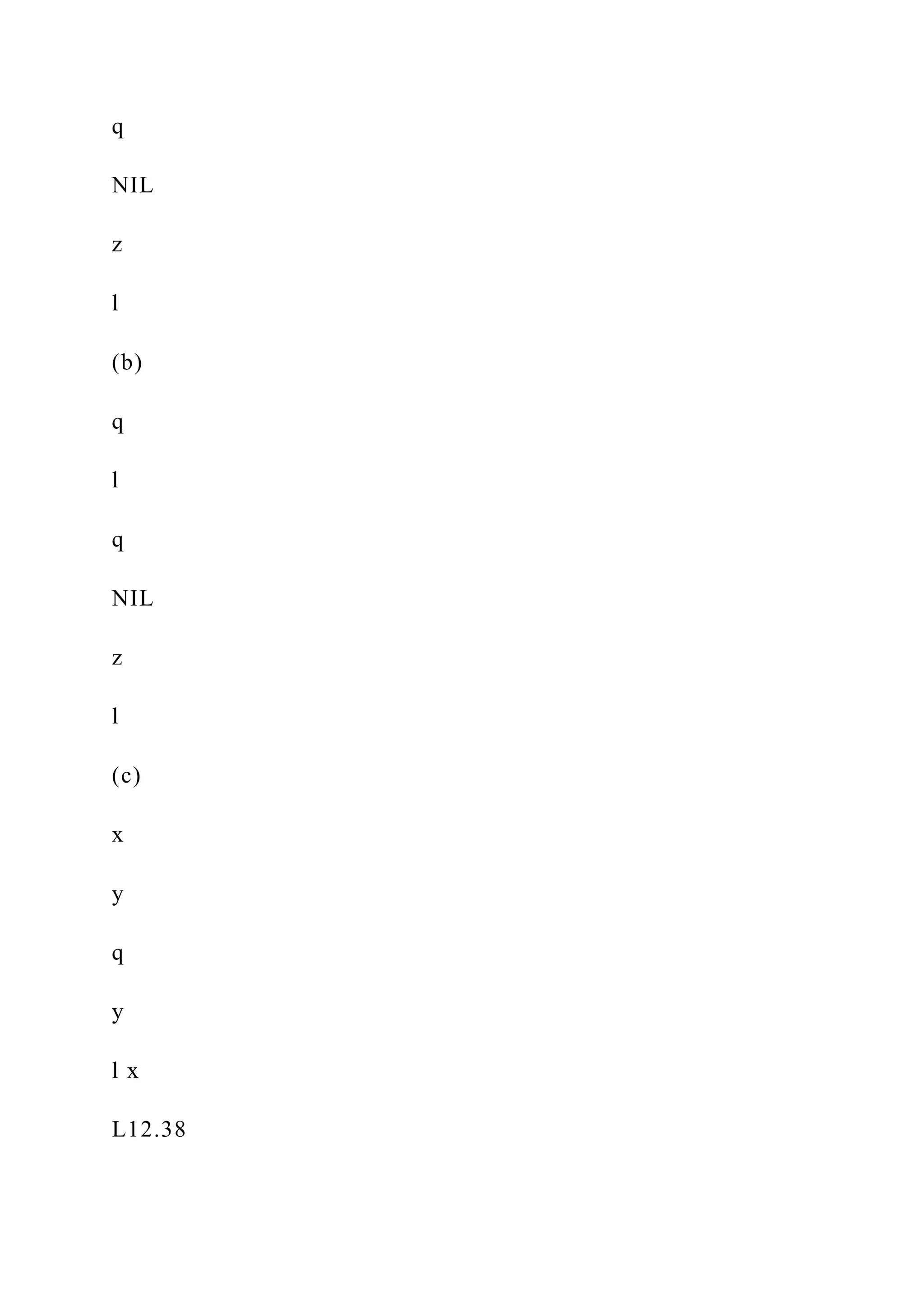

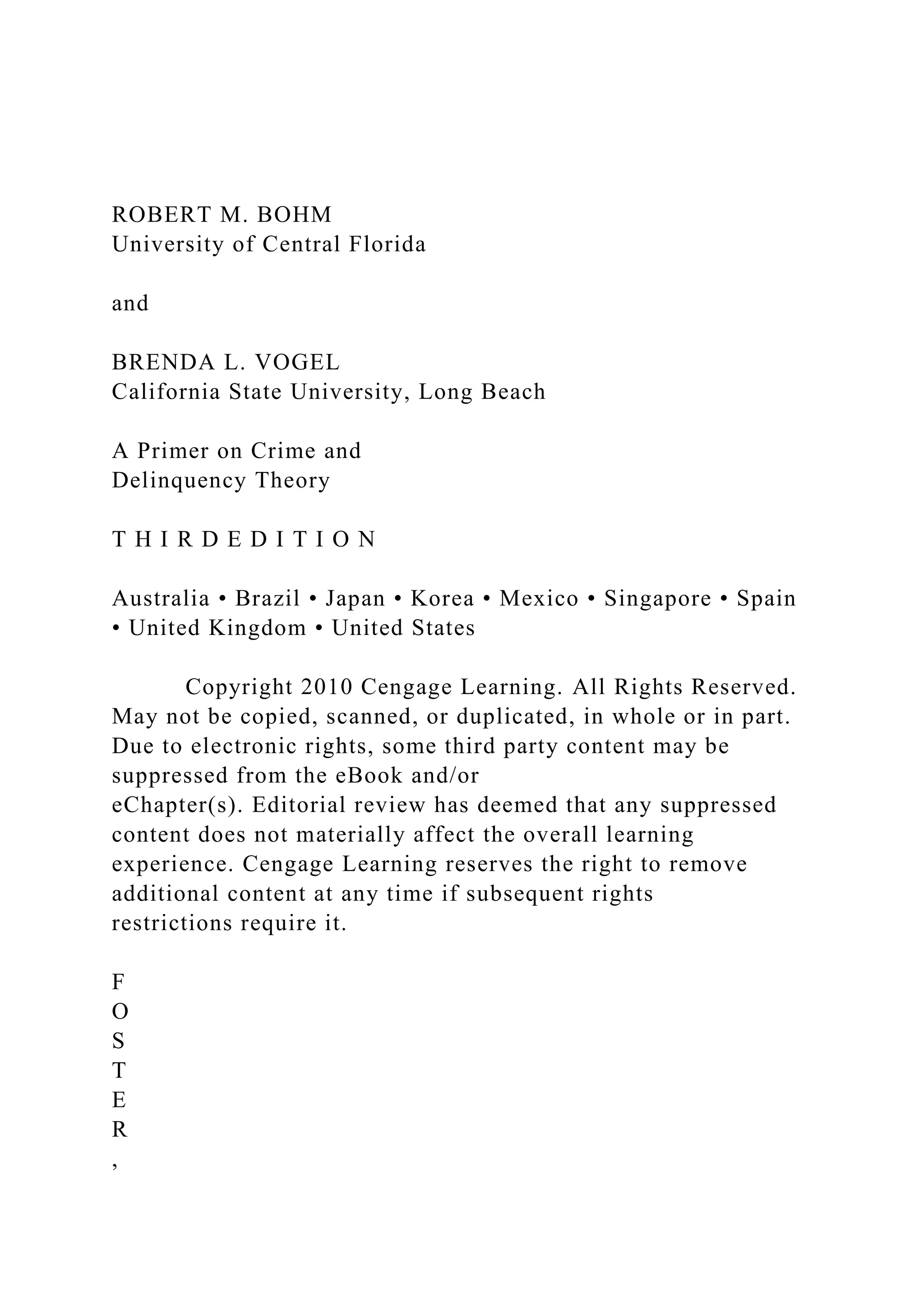

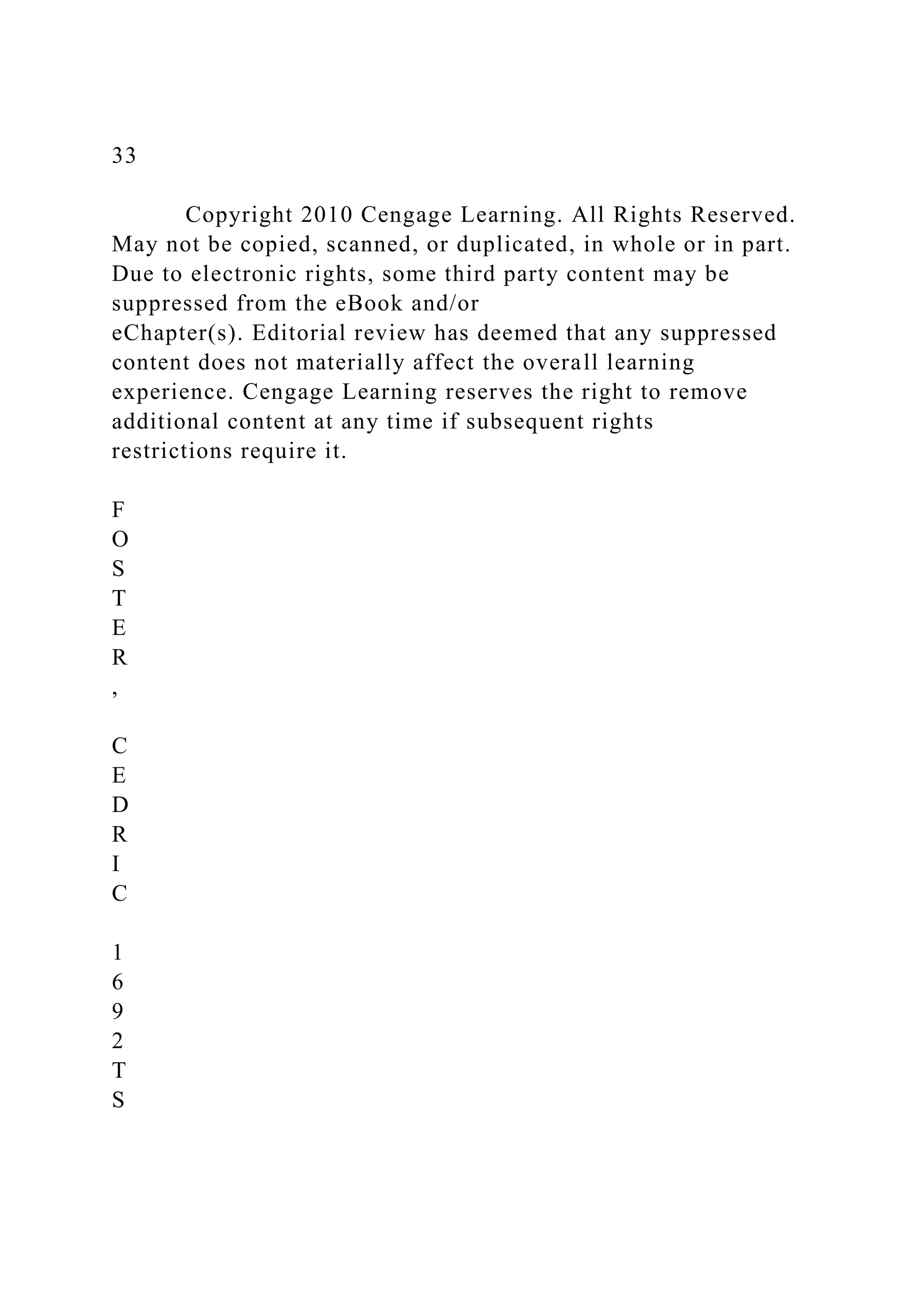

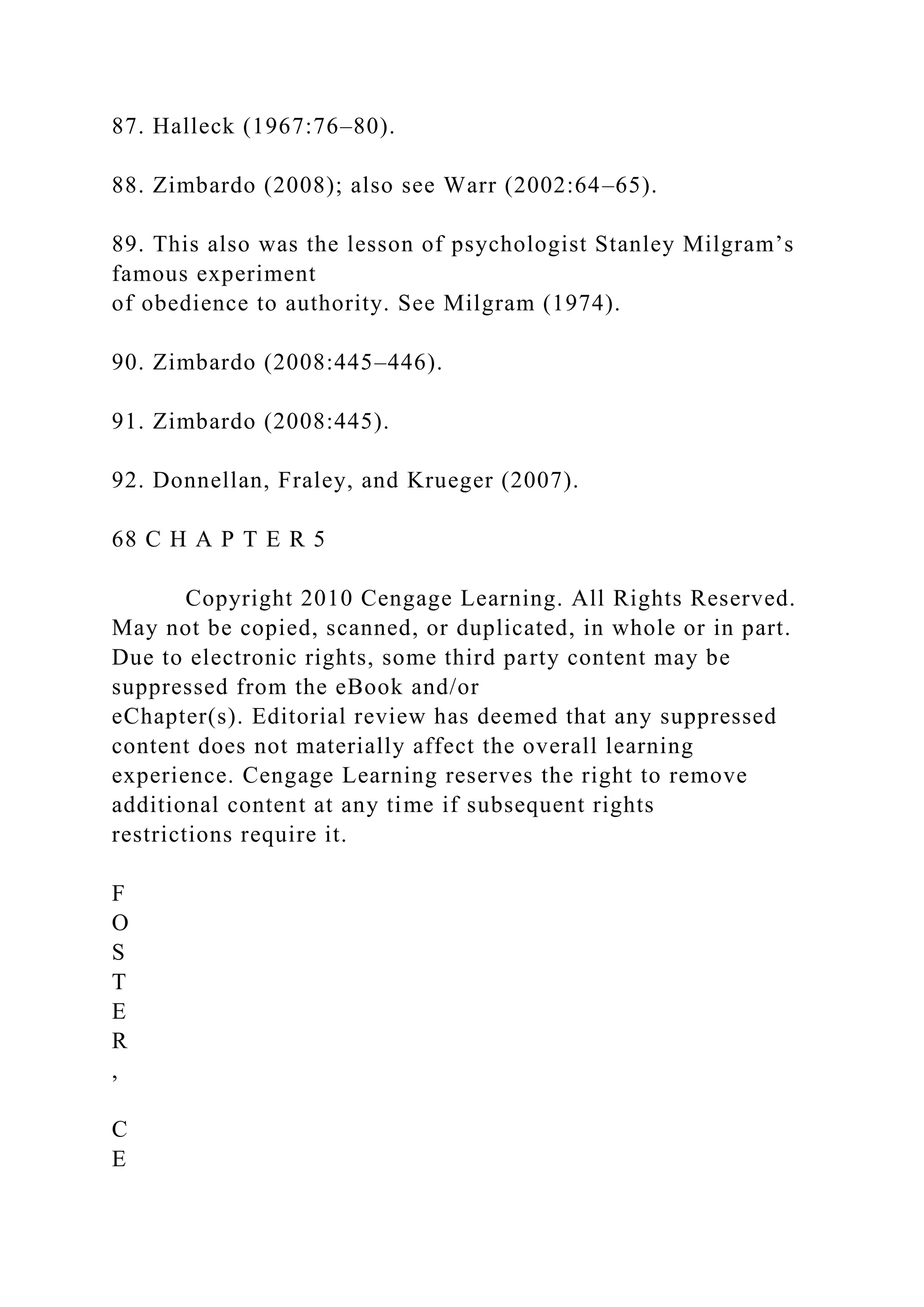

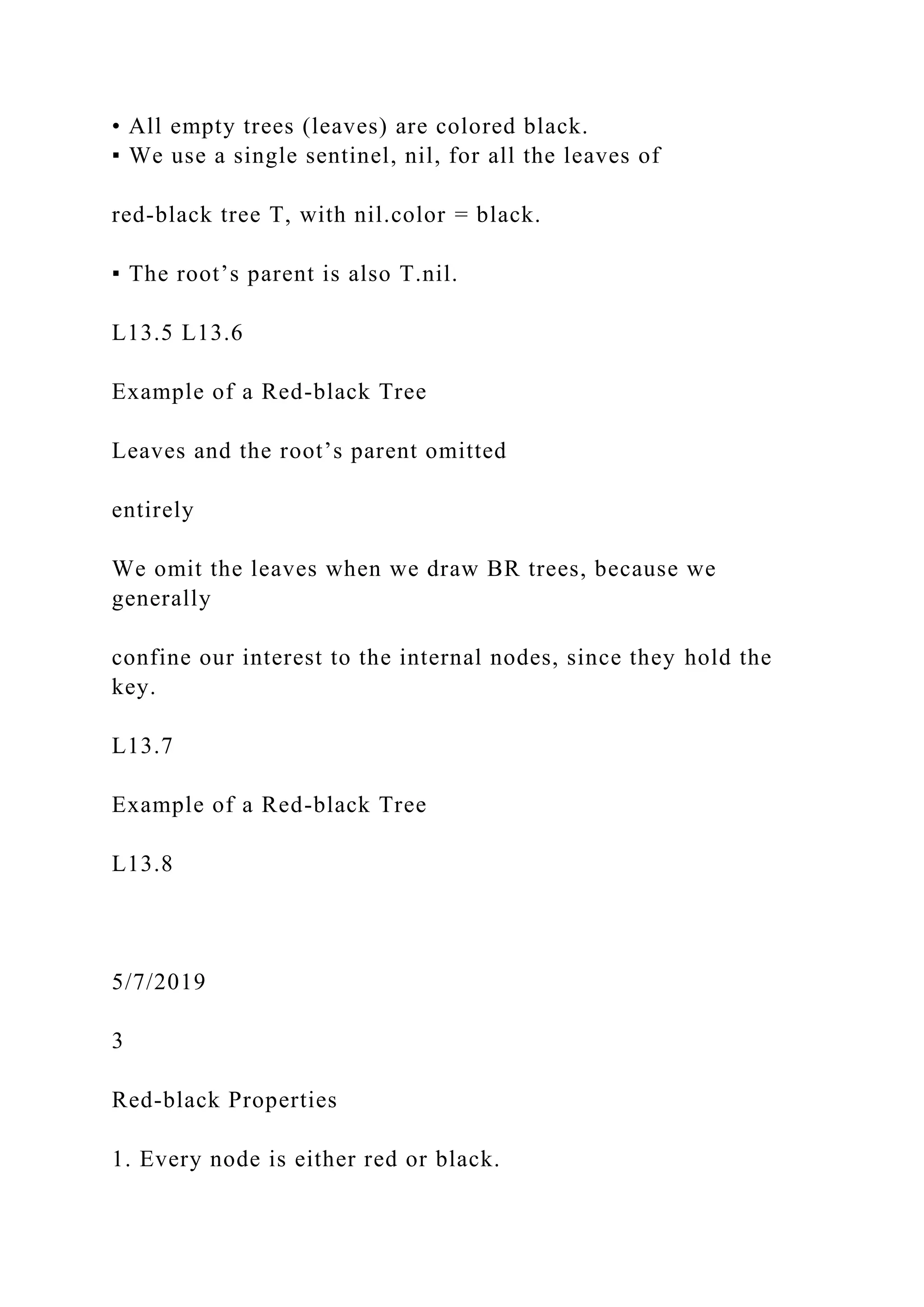

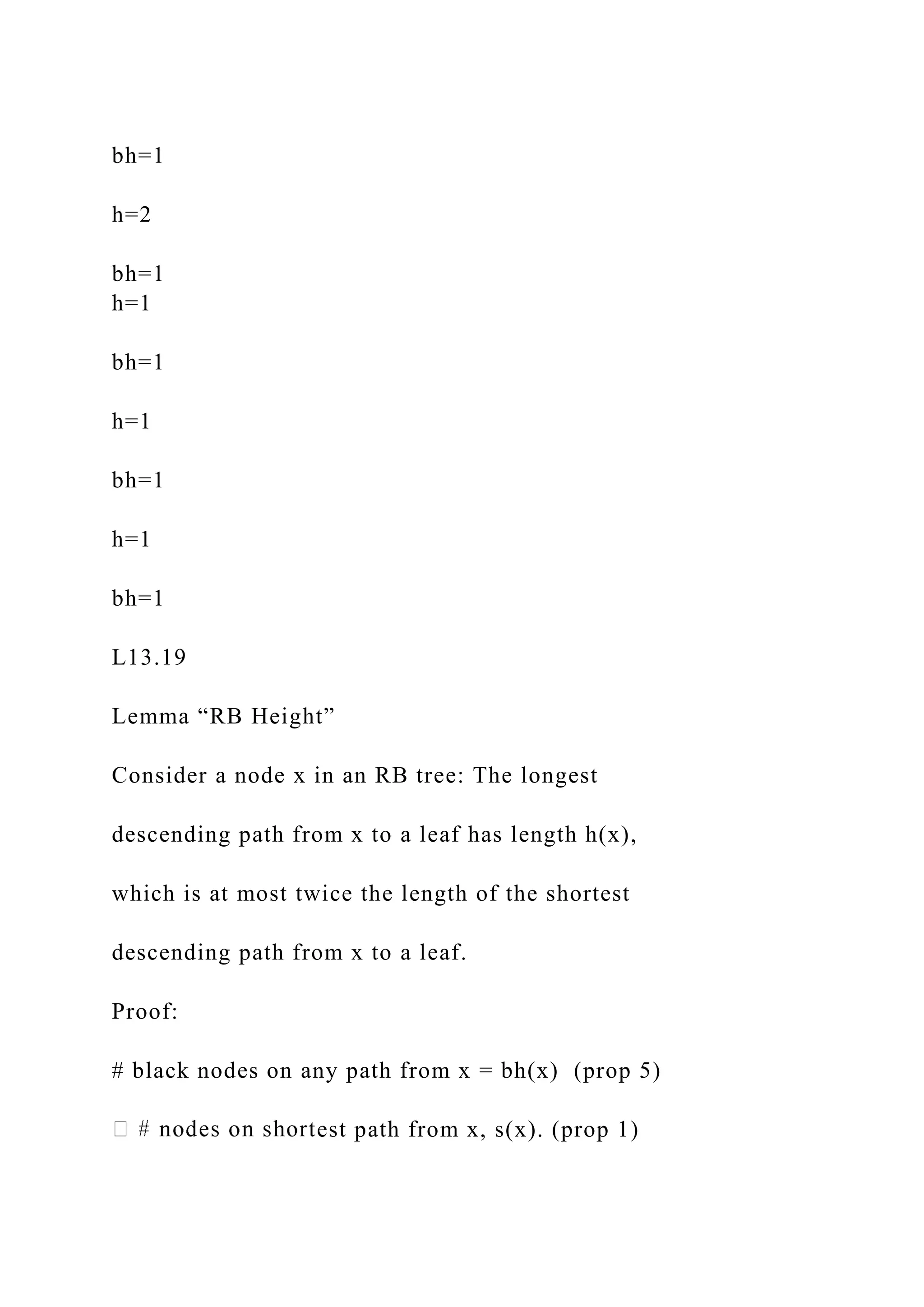

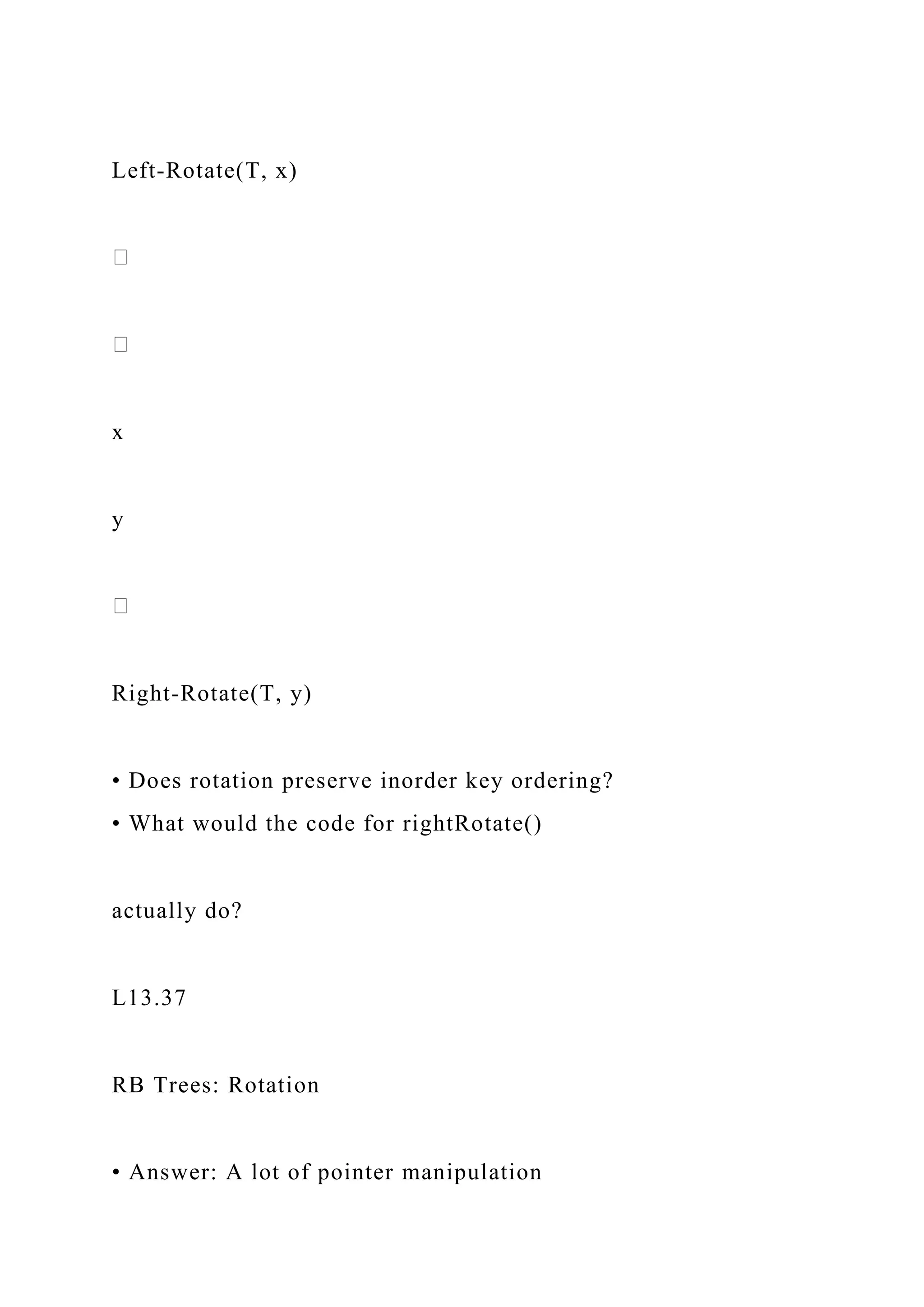

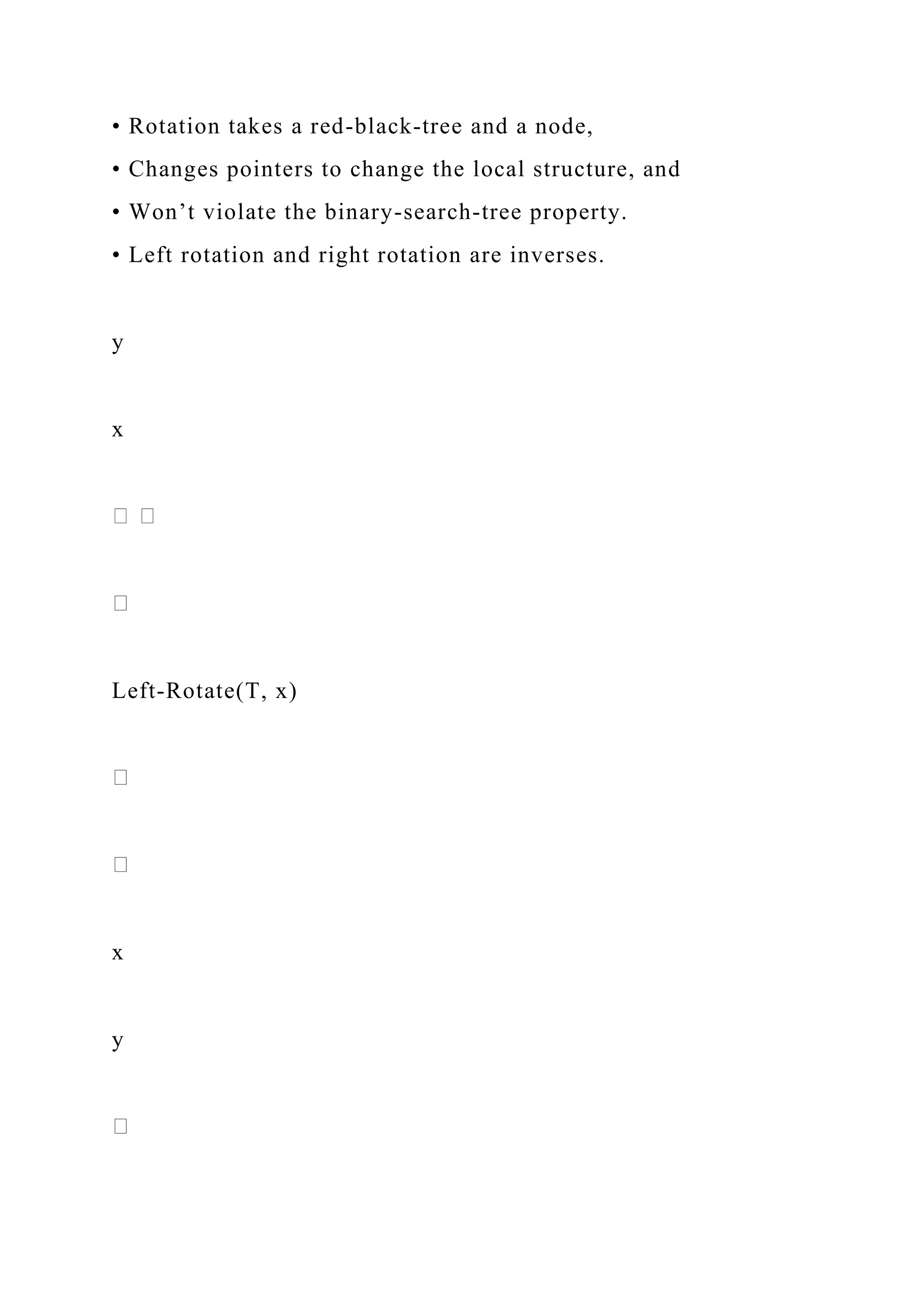

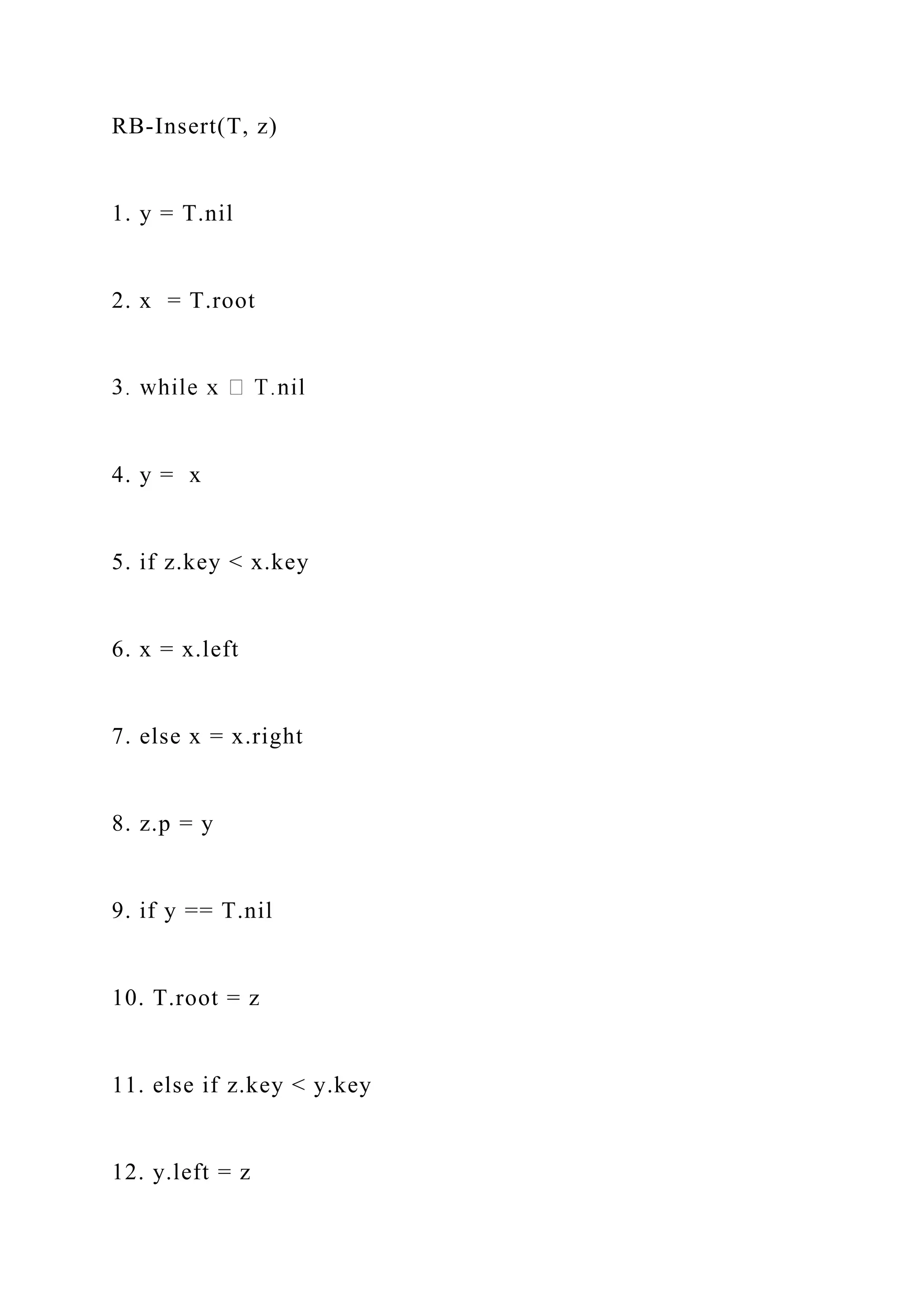

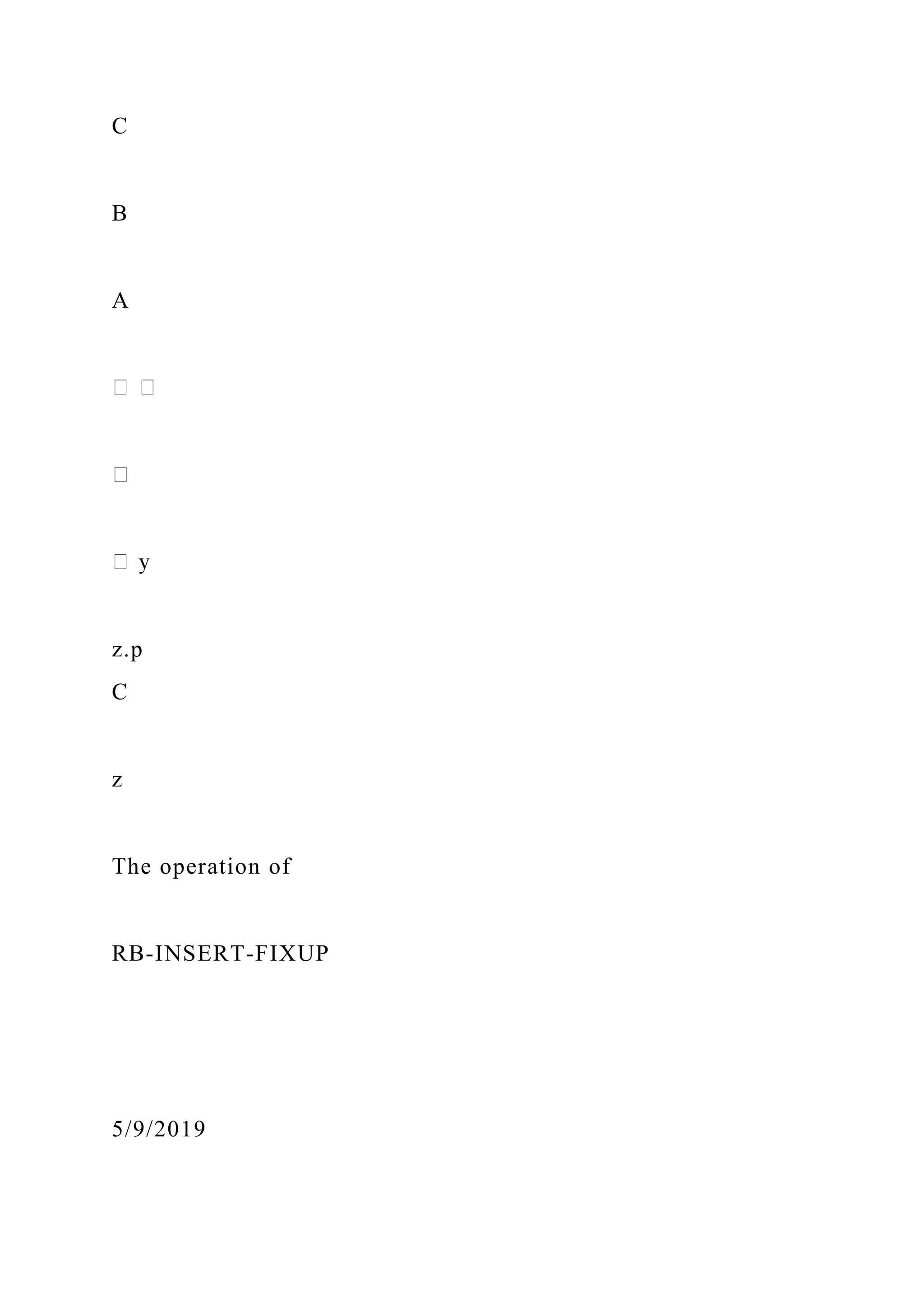

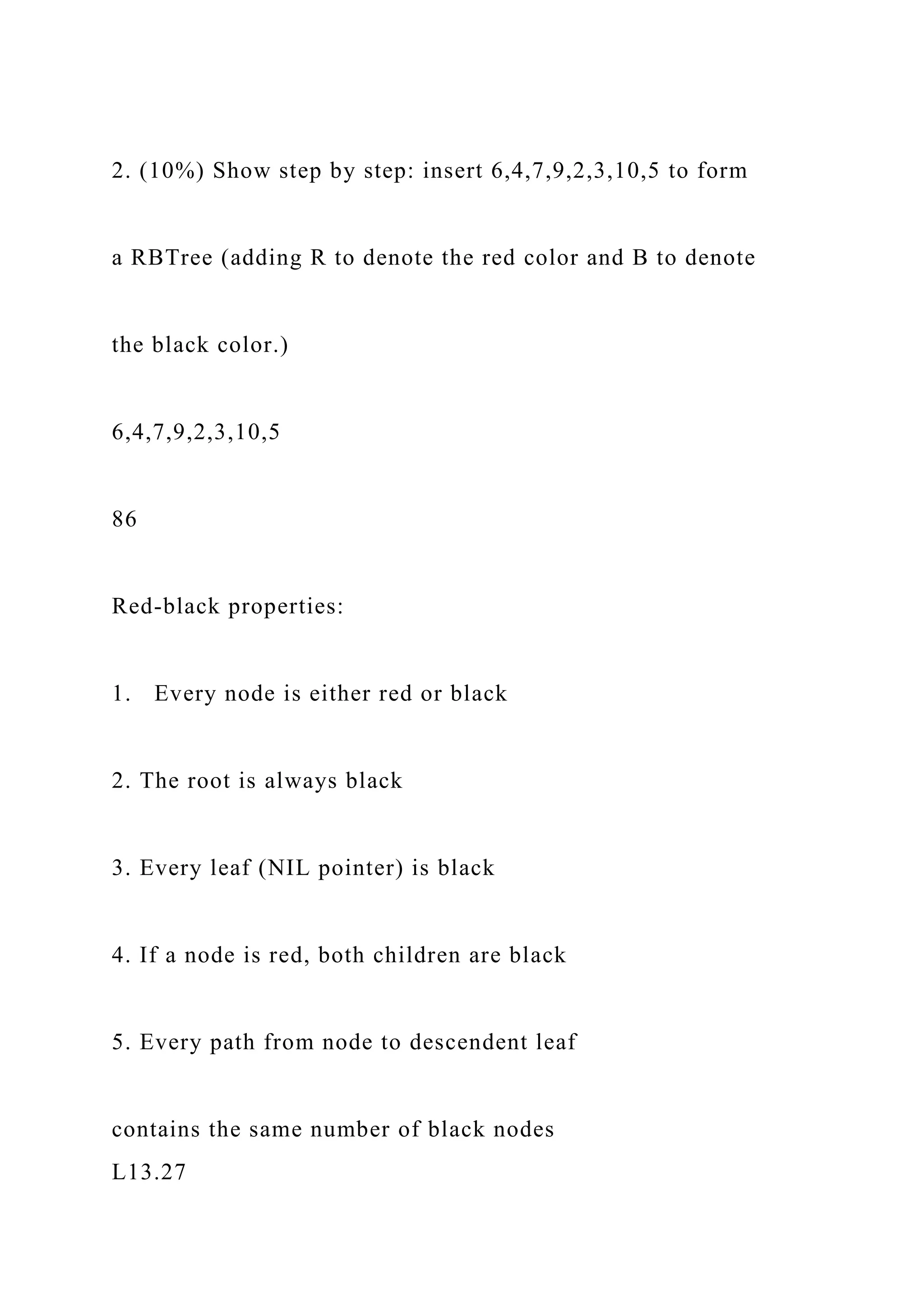

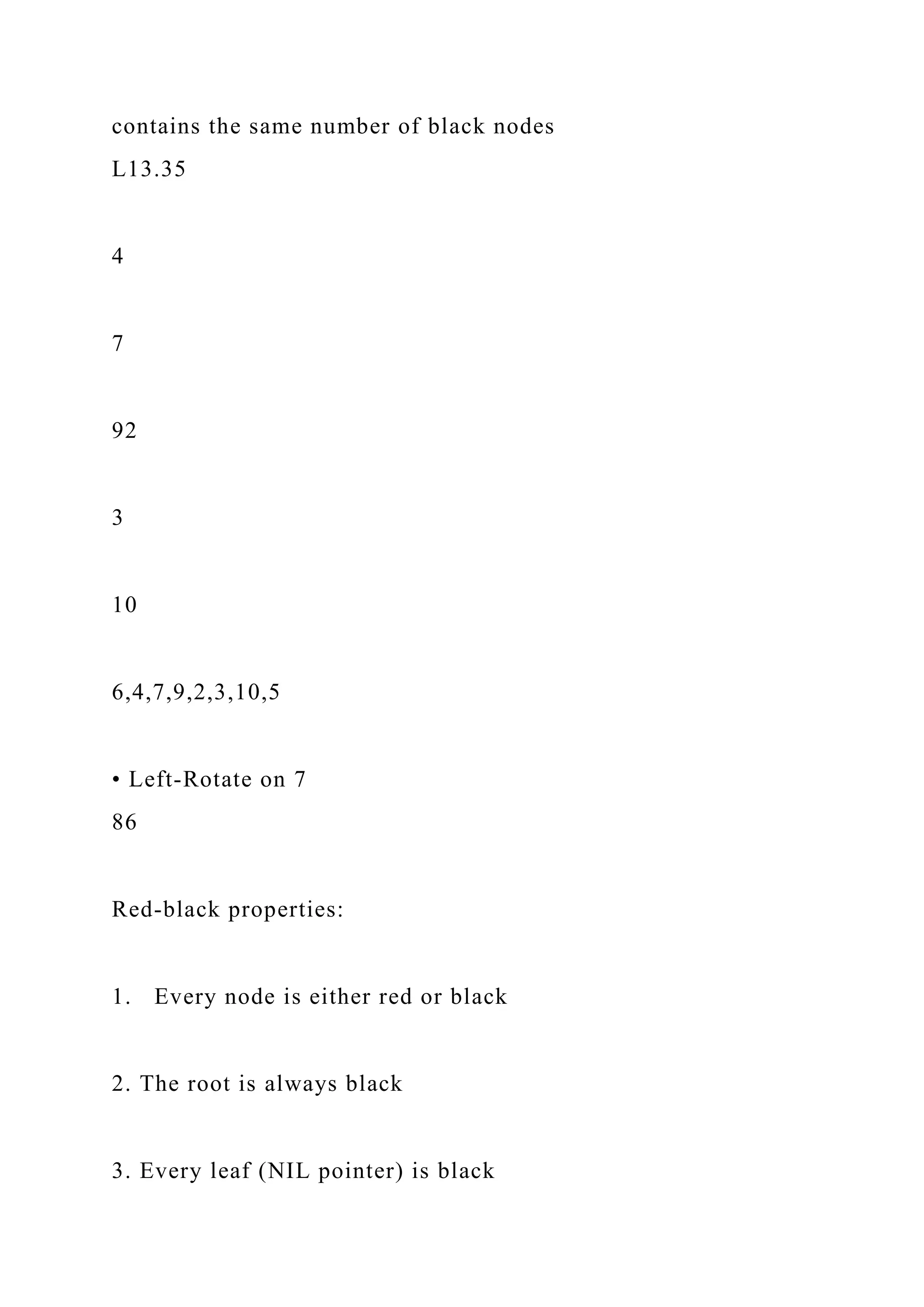

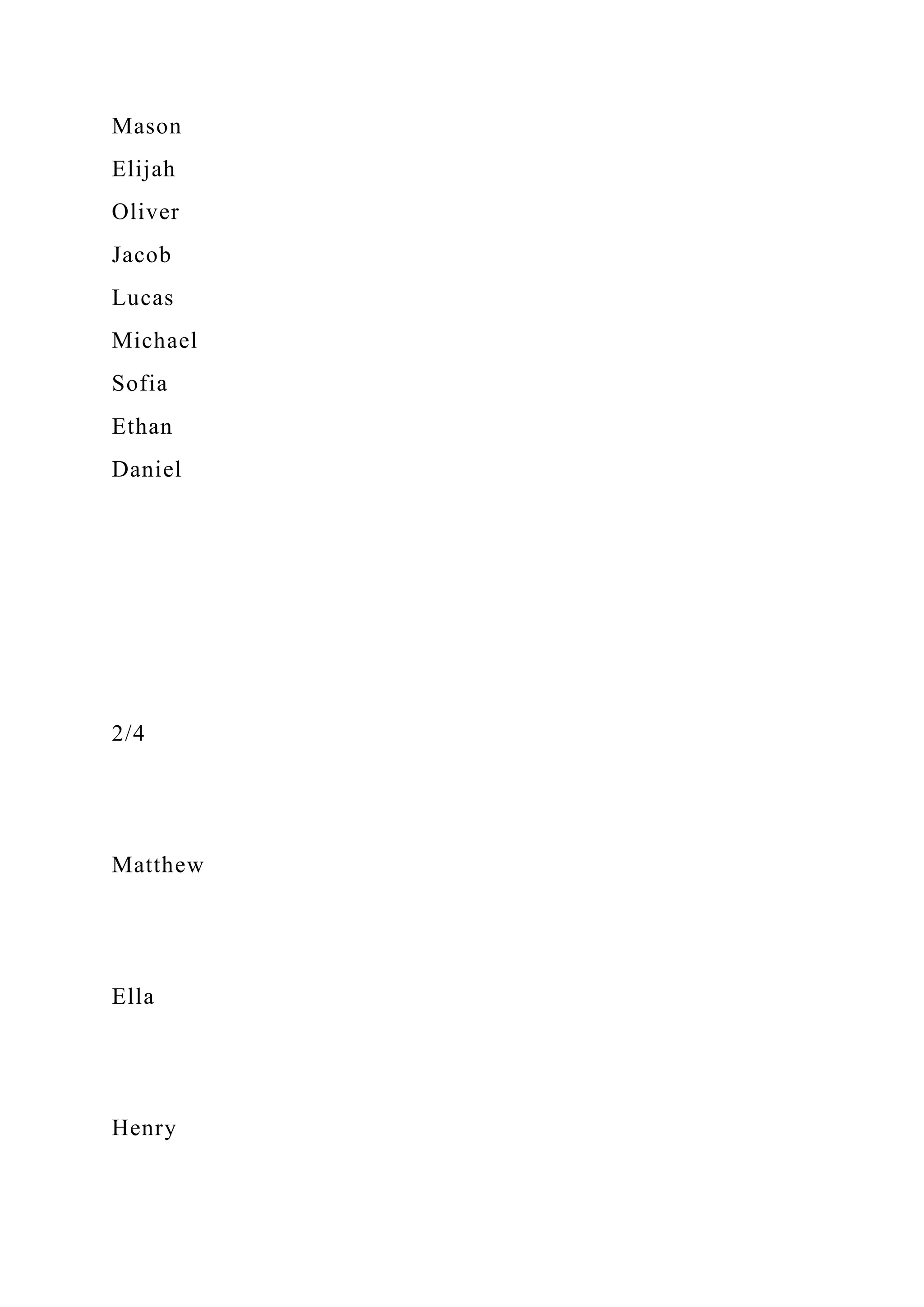

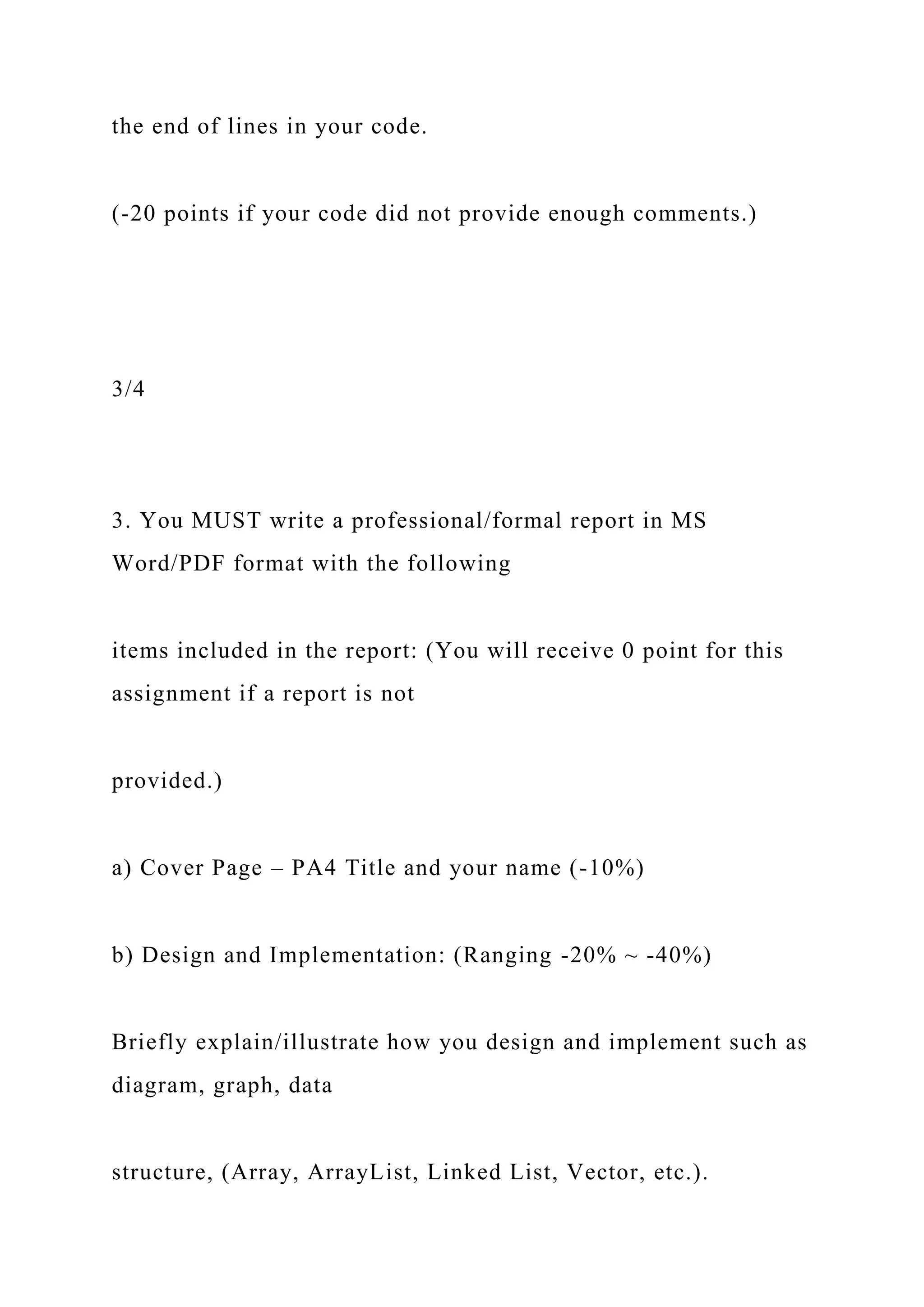

![L12.22

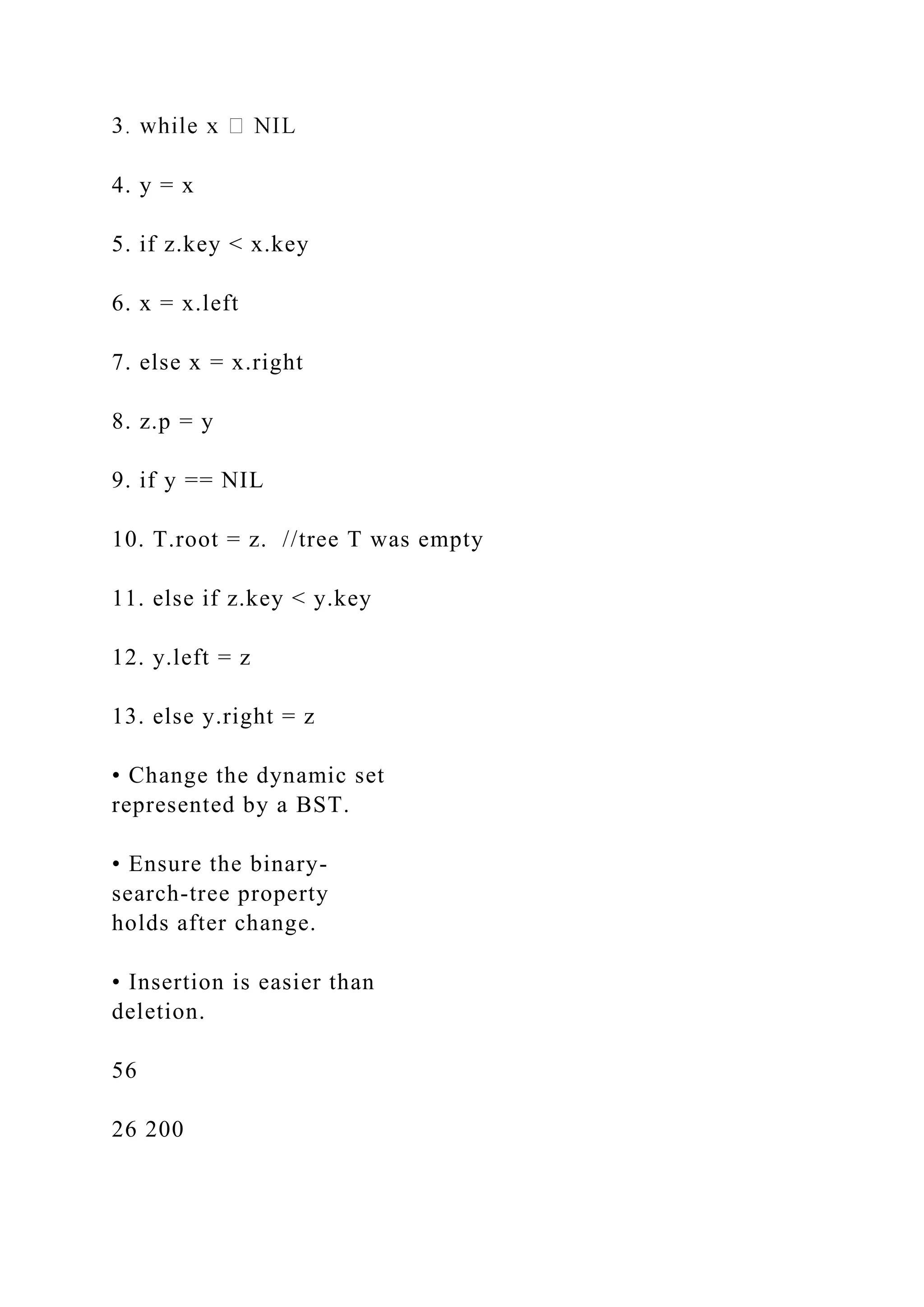

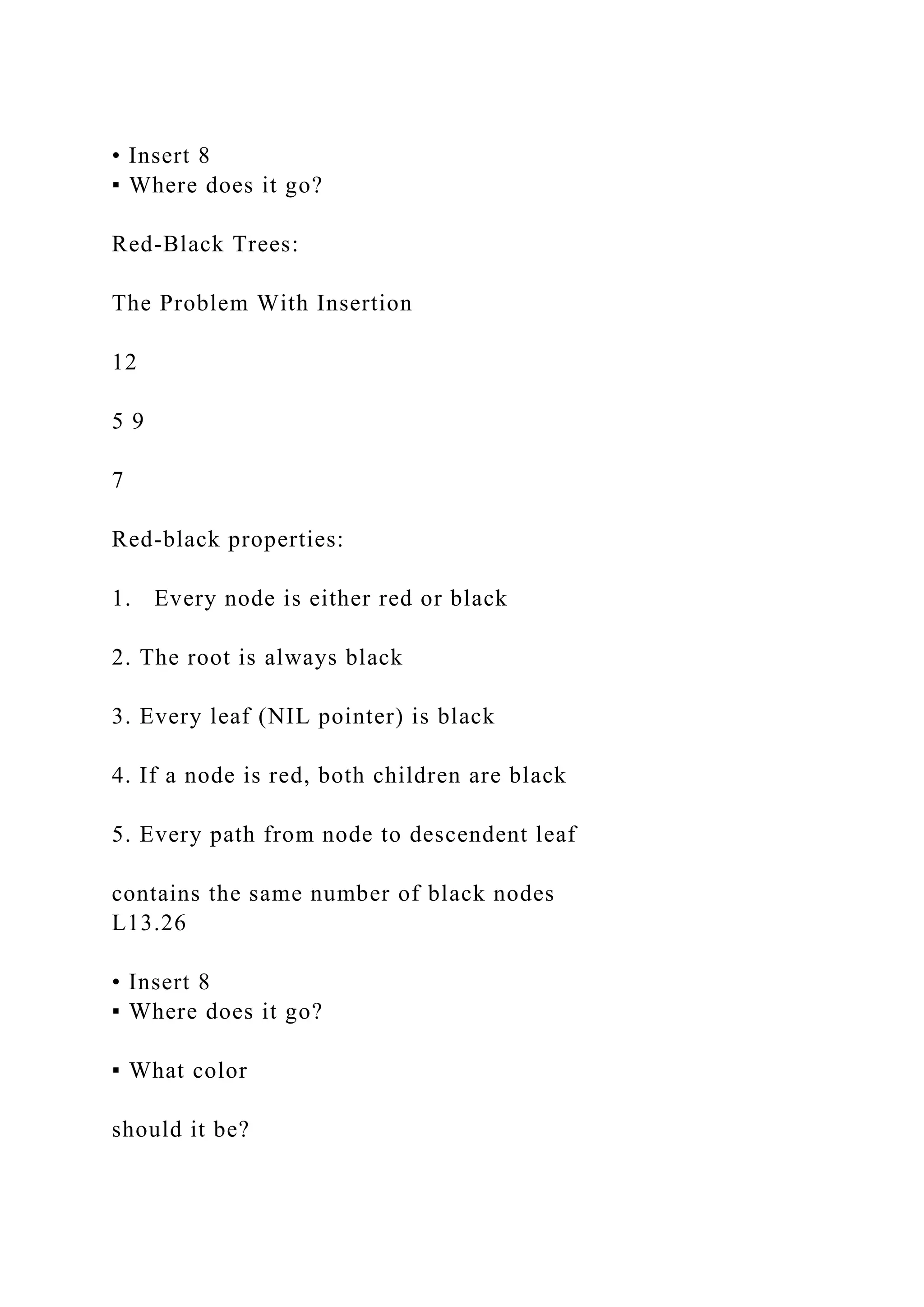

Sorting With BSTs

• Average case analysis

▪ It’s a form of quicksort!

for i=1 to n

TreeInsert(A[i]);

InorderTreeWalk(root);

3 1 8 2 6 7 5

5 7

1 2 8 6 7 5

2 6 7 5

3

1 8

2 6

5 7

L12.23

Sorting with BSTs

• Same partitions are done as with quicksort, but

in a different order](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-19-2048.jpg)

![ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the

copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored or used

in

any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical,

including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning,

digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information networks, or

information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted

under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright

Act,

without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For product information and

technology assistance, contact us at Cengage Learning

Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706

For permission to use material from this text or product,

submit all requests online at cengage.com/permissions

Further permissions questions can be emailed to

[email protected]

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010926703

ISBN-13: 978-0-495-80750-6

ISBN-10: 0-495-80750-8

Wadsworth

20 Davis Drive

Belmont, CA 94002-3098

USA

Cengage Learning is a leading provider of customized learning

solutions with office locations around the globe, including

Singapore, the United Kingdom, Australia, Mexico, Brazil, and

Japan. Locate your local office at www.cengage.com/global](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-37-2048.jpg)

![C

E

D

R

I

C

1

6

9

2

T

S

control of criminology from psychologists who then dominated

the field and with

whom psychiatrists were in competition. Laub and Sampson

(1991:1404) attribute

the heated debates about criminological theory between Edwin

Sutherland and

Shelden and Eleanor Glueck to “their respective methodological

and disciplinary

biases.” Daly and Chesney-Lind (1988:500) maintain that “a

major feminist project

today is to expose the distortions and assumptions of

androcentric science [which

reveals] that an ideology of objectivity can serve to mask men’s

gender loyalties as

well as loyalties to other class or racial groups.” Cullen,

Gendreau, Jarjoura, and

Wright (1997:387) argue that Herrnstein and Murray’s showing

that IQ is a pow-

erful predictor of crime in their controversial book The Bell](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-62-2048.jpg)

![Cover Image: Corbis Yellow

Compositor: Pre-PressPMG

© 2011, 2001, 1997 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the

copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored or used

in

any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical,

including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning,

digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information networks, or

information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted

under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright

Act,

without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For product information and

technology assistance, contact us at Cengage Learning

Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706

For permission to use material from this text or product,

submit all requests online at cengage.com/permissions

Further permissions questions can be emailed to

[email protected]

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010926703

ISBN-13: 978-0-495-80750-6

ISBN-10: 0-495-80750-8

Wadsworth

20 Davis Drive

Belmont, CA 94002-3098](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-68-2048.jpg)

![criminals and noncriminals without adding the value judgment.

In any event,

several different methodologies have been employed to detect

physical differences

between criminals and noncriminals. They are physiognomy,

phrenology, criminal

anthropology, study of body types, heredity studies (including

family trees, statistical

comparisons, twin studies, and adoption studies) and, in the last

twenty years or so,

studies based on new scientific technologies that allow, for

example, the examina-

tion of brain function and structure.

P H Y S I O G N O M Y A N D P H R E N O L O G Y

Physiognomy is the judging of character or disposition from

facial and other

physical features. The Greek philosopher Aristotle is credited

with writing the

first systematic physiognomic treatise.7 In his discussion of

noses, for example,

Aristotle wrote:

[T]hose with thick bulbous ends belong to persons who are

insensitive,

swinish, and prone to acts of theft, fraud, and intemperance;

sharp-

tipped noses belong to the irascible, those easily provoked and

liable

to assaultive behavior and ruffianism; rounded, large obtuse

noses are

characteristic of the magnanimous; slender, eagle-like hooked

noses

belong to the noble; round-tipped noses to the hedonistic; noses](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-73-2048.jpg)

![association of the physical characteristics with criminality, then

the result is circular

reasoning.36 In other words, crime is caused by biological

inferiority, which is itself

indicated by the physical characteristics associated with

criminality.

A second problem is the assumption that apes and other lower

animals are

savage and criminal. As Harvard paleontologist, evolutionary

biologist, and histo-

rian of science Stephen Gould (1941–2002) remarked, “If some

men look like apes,

but apes be kind, then the argument fails.”37 In an effort to

make the dubious

connection, Lombroso had to engage in a tortured

anthropomorphism. As Gould

related:

He [Lombroso] cites, for example, an ant driven by rage to kill

and

dismember an aphid; an adulterous stork who, with her lover,

murdered

her husband; a criminal association of beavers who ganged up to

murder

a solitary compatriot; a male ant, without access to female

reproductives,

who violated a (female) worker with atrophied sexual organs,

causing

her great pain and death; he even refers to the insect eating of

certain

plants as an “equivalent of crime.”38

Despite those problems, Lombroso’s theory was popular in the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-87-2048.jpg)

![“crucial for most of the brain’s functions, including mood,

behavior, [and]

emotion.”91 In particular, serotonin, norepinephrine, and

dopamine all have been

implicated in antisocial and impulsive behaviors. Serotonin is

widely held to be a

“braking system” for impulsive drives.92 Abnormally low levels

of serotonin have

been linked to antisocial behaviors involving impulsivity,

including substance

abuse, suicidal impulses, and completed suicides.93 On the

other hand, high levels

of dopamine have been associated with violence, aggression,

gambling, and

substance abuse.94 Apparently, cocaine increases the level of

dopamine, which

activates the limbic system to produce pleasure.95 Finally,

elevated levels of norepi-

nephrine also have been correlated with aggressive behavior.96

While level and

activity of neurotransmitters is considered a heritable

characteristic, neurotransmit-

ters are highly sensitive to environmental manipulations.97

Sociocultural factors

such as socioeconomic status, stress, and nutrition have been

found to influence

the relationship between neurotransmitters and behavior.98

The relationship between low arousal and antisocial and

criminal behaviors

has been found to be “the strongest psychophysiological

finding” in modern bio-

criminological research.99 Psychophysiology refers to how a

psychological state or](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-108-2048.jpg)

![Compositor: Pre-PressPMG

© 2011, 2001, 1997 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the

copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored or used

in

any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical,

including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning,

digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information networks, or

information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted

under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright

Act,

without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For product information and

technology assistance, contact us at Cengage Learning

Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706

For permission to use material from this text or product,

submit all requests online at cengage.com/permissions

Further permissions questions can be emailed to

[email protected]

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010926703

ISBN-13: 978-0-495-80750-6

ISBN-10: 0-495-80750-8

Wadsworth

20 Davis Drive

Belmont, CA 94002-3098

USA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-135-2048.jpg)

![that criminals are feebleminded.5

A problem arose when the Army Psychological Corps adopted

Goddard’s

standard as a criterion for fitness for military service. When

intelligence tests

were administered to draftees for World War I, it was

discovered using

Goddard’s criterion that about one-third of them were

feebleminded.6 Whether

that was an accurate indicator of the intelligence level of the

population at the

time (as represented by the draft army) must remain the object

of conjecture.

However, as a practical matter, the army was not about to

eliminate nearly

one-third of draftees because of low-level intelligence.

Consequently, Goddard

changed his conclusions. In 1927, he wrote:

The war led to the measurement of intelligence of the drafted

army

with the result that such an enormous proportion was found to

have an

intelligence of 12 years and less that to call them all feeble

minded was

an absurdity of the highest degree.… We have already said that

we

thought 12 was the limit, but we now know that most of the

twelve,

and even of the ten [IQ = 63] and nine [IQ = 56], are not

defective.7

In 1931, E. H. Sutherland reviewed approximately 350 studies

on the relation-

ship between intelligence and delinquency and criminality.8 The](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-141-2048.jpg)

![accepted and 0 point will be

given. [No jar file or your code is not runnable (test it before

submission: java -jar

filename.jar): -20 points]

2. The deadline to submit/upload your zip file to Canvas is

before 11:59pm on Tuesday,

5/21/2019. After deadline, the submission link will be closed.

4/4

Warning: DO NOT wait until the last minute to upload your

files to Canvas. It has been

happening all the time that it took forever to upload files to

Canvas during the last

hour/minute. No excuse for late submission.

Grading Criteria](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5220191cs146datastructuresandalgorithmsc-221201210134-446698d9/75/5220191CS146-Data-Structures-and-AlgorithmsC-docx-281-2048.jpg)