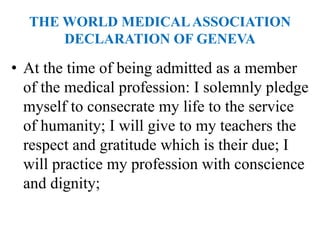

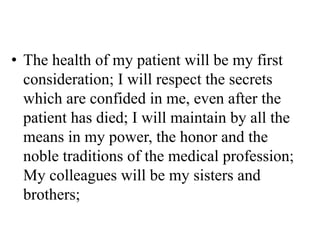

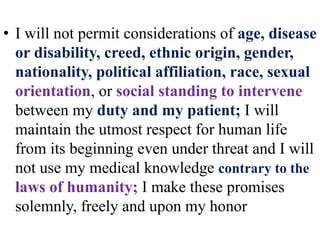

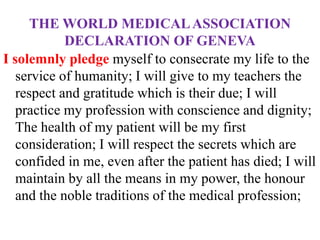

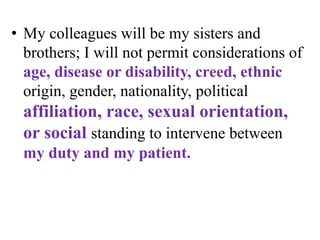

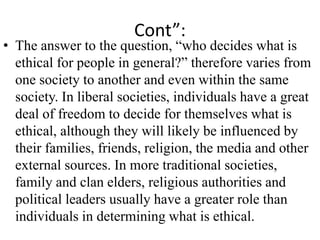

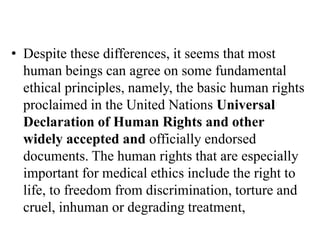

This document discusses key concepts in medical ethics, including the physician-patient relationship, respect and equal treatment of patients, informed consent, and confidentiality. It notes that while medical ethics can vary between countries and over time, core principles like compassion, competence, and autonomy remain important. The World Medical Association plays an important role in establishing global ethical standards for physicians. Ultimately, individual physicians must apply ethical principles to specific situations and make their own decisions.