2016 828 post hearing sanctions brief, George Sansoucy, GES

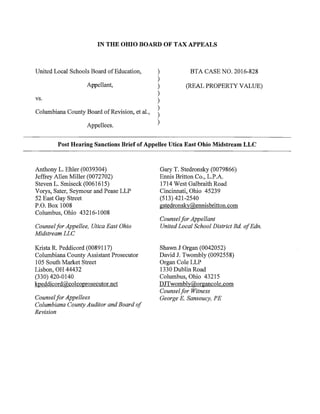

- 1. IN THE OHIO BOARD OF TAX APPEALS United Local Schools Board ofEducation, ) BTA CASE NO. 2016-828 ) Appellant, (REAL PROPERTY VALUE) ) ) vs. ) ) Columbiana County Board ofRevision, et al. ) ) Appellees. Post Hearing Sanctions Brief of Appellee Utica East Ohio Midstream LLC Anthony L. Ehler (0039304) Jeffrey Allen Miller (0072702) Steven L. Smiseck (0061615) Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease LLP 52 East Gay Street P.O. Box 1008 Columbus, Ohio 43216-1008 Gary T. Stedronsky (0079866) Eimis Britton Co., L.P.A. 1714 West Galbraith Road Cincinnati, Ohio 45239 (513)421-2540 gstedronskv@ennisbritton.com Counselfor Appellant UnitedLocal School District Bd. ofEdn. Counselfor Appellee, Utica East Ohio Midstream LLC Krista R. Peddicord (0089117) Columbiana County Assistant Prosecutor 105 South Market Street Lisbon, OH 44432 (330) 420-0140 kpeddicord@,colcoprosecutor.net Shawn J Organ (0042052) David J. Twombly (0092558) Organ Cole LLP 1330 Dublin Road Columbus, Ohio 43215 DJTwomblv@,organcole.com Counselfor Witness George E. Sansoucy, PE Counselfor Appellees Columbiana County Auditor andBoard of Revision

- 2. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Summary ofthe Case and Questions Before the Board 1 I. The Board’s Power To Sanction a Witness 5 II. The Board’s has power to bar an unreliable witness from testifying as a sanction.................................................................................................... A. 5 Mr. Sansoucy has no constitutionally protected “right to testify The Board should sanction an expert witness when it is clear that witness deliberately testified falsely......................................................................... The Board should sanction any witness when it is clear the witness perjured himselfunder Ohio law..................................................... Knowingly making a false statement” for purposes ofthe Ohio perjury statute includes making statements where the witness is consciously ignorant ofthe truth ofthe statement........................... When is false testimony material?................................................... The Method Followed in This Briefwith Regard To Addressing Mr. Sansoucy’s False Testimony....................................................................................................... The Work Mr. Sansoucy Claimed To Have Performed........................................... Despite purporting to be a report of expert testimony on engineering facts, the Sansoucy report does not set forth any facts relevant to the real versus personal property question........................................................................... Work Mr. Sansoucy claimed to have performed to support his conclusions Mr. Sansoucy claimed in his report to have done an enormous amount ofwork to support his real versus personal property determinations.................................................................................. 99 7 B. C. 10 1. 13 2. 14 17 3. III. 18 19 IV. A. 20 24 B. 1. 24 Mr. Sansoucy testified to enormous amounts ofreview and study ofKensington documents and that analysis was the basis ofhis real versus personal property determinations.......................................... Sansoucy’s false testimony specific to piping systems..................... Made up testimony regarding non-existent fire water system and pilot gas systems................................................ 2. 26 34 3. a. 43 1

- 3. Made-up testimony regarding non-existent sanitary drain system................................................................................... Made up testimony regarding nitrogen rejection unit........... Made up testimony regarding tanks at Kensington storing non existent products made by non-existent equipment.......................... False testimony regarding deethanizers and tanks to store ethane at Kensington............................................................. False testimony regarding pure butane being stored in tanks at Kensington........................................................................ False testimony regarding propane being extracted as a pure product at Kensington, stored in tanks at Kensington, and shipped in a non-existent “pure propane” pipeline........ Mr. Sansoucy’s testimony regarding ethane, butane and propane as products at Kensington is not rationally explainable............................................................................ Mr. Sansoucy’s False Testimony Regarding Piping System Quantity Survey Method Costing......................................................................................................... b. 48 52 c. 4. 56 a. 61 b. 62 c. 64 d. 68 V. 69 84 Conclusion VI. 87 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 11

- 4. Siimmary of the Case and Questions Before the Board. I. At the inception, Appellee Utica East Ohio (“UEO”) acknowledges that it filed a lengthy sanctions motion. It is procedurally unusual at the Board to have both pre- and post-hearing briefs. UEO will clarify then that this brief is intended to supersede its original motion. In that regard, this briefrepeats some ofthe factual assertions and arguments made in that motion. Thus, the Board can rely entirely upon UEO’s post-hearing briefs to establish its position. That said, UEO is not aware of any misstatements offact or law in that original Motion and stands by it in its entirety. The pending Sanctions Motion arose from a tax year 2015 case involving two primary questions associated with real property tax at the natural gas processing facility in Kensington, Ohio. First, there was a plain vanilla valuation dispute regarding the real property shown on the County Auditor’s property record card. Second, there was an allegation that the County Auditor failed to correctly classify real property. Mr. Sansoucy’s report assigned $16,633,394 in value to the real property set forth on the property record card. See Appellant’s Exh. 1 at 81. His report assigned a value of $56,259,606 to property that he claimed was real property but which he alleged was misclassified as personal property. The total value he claimed for the Kensington site was $72,893,000. Appellee’s own appraisers opined that the property on the record card was undervalued. Thus, there was not a large difference between the County Auditor’s 2016 valuation and Appellee’s own appraisers. The controversy mainly centered on property classification. The 2015 dispute ultimately was settled at $12,665,500 in value. This amount was the County Auditor’s 2016 value which was established well prior to delivery ofMr. Sansoucy’s report. The settlement addressed only the valuation ofthe real property listed on the property

- 5. record card as prepared by the County Auditor. No property at Kensington was reclassified from personal to real as a result of the settlement. Nearly all ofMr. Sansoucy’s questionable testimony occurred with reference to the $56M misclassification issue and that issue was conceded by Appellant in its entirety in settlement. Thus, despite opposing counsel’s attempt to characterize Mr. Sansoucy’s efforts as having been instrumental in achieving settlement, the settlement was reached in spite ofMr. Sansoucy and was based on the County Auditor’s property classification and value certified prior to the Sansoucy report. It is self-evident that an appraisal ofthe real property on the property record card at the site should not cost nearly $400,000, which is the amount Mr. Sansoucy invoiced the school district. Appellee was able to retain an expert appraiser for that purpose for about $10,000. Mr. Sansoucy’s property classification effort was a superfluous add-on to the actual real property valuation case. Had he been truthful with his own client from the inception, much or all ofproperty classification issue would not have been raised. It certainly would have not have encompassed $56M of assets including process piping, tanks and electrical equipment. Mr. Sansoucy’s claim that the Columbiana County Auditor simply ignored property classification at Kensington was always baseless. A***we found no indication that the auditor did anything ofthe sort. Q. In your estimation, he misclassified as nontaxable? A. He just didn't do it. Q. Didn't do it? A. Yeah. We found no indication that he got $393 million worth ofproperty inventory and went through and broke out the real property or tried to break out the real property. We found no indication that any ofthat existed. 2

- 6. Appellee UEO’s Exh. 2 at 173 (Sansoucy Deposition); see also H.R. Vol. 1: 9. (“***there's certainly no evidence that the Auditor's Office had done any ofthis work, so we have done the 1 work to separate it out.”). As a result oftestimony given by Mr. Sansoucy at the Board’s hearing conducted on the tax merit appeal, UEO filed its Motion for Sanctions against expert witness George Sansoucy. The record establishes that Mr. Sansoucy (1) failed to perform the work he claimed to have performed, (2) testified falsely regarding items of equipment, piping systems and products that do not exist, and (3) made flagrantly false representations regarding his quantity survey method of costing piping systems. Much ofthe false testimony UEO identified has been conceded to be incorrect either by Mr. Sansoucy, his counsel, or both. Counsel for Mr. Sansoucy argues primarily that it is impossible to know Mr. Sansoucy’s intent when he offered the incorrect testimony. To opposing counsel, sanctions are not appropriate because it is impossible to read Mr. Sansoucy’s mind to determine ifhe purposefully misrepresented the truth. Even ifMr. Sansoucy intentionally provided false testimony, opposing counsel argues that the misrepresentations were not material (and thus presumably not worthy of sanction).^ Alternatively, opposing counsel proposes that even ifthe false testimony was material, the Board lacks authority to issue a decision pointing out the resulting lack oftestimonial reliability and bar him from testifying in the future on that basis as a sanction. ' There are two hearing transcripts that will be referenced in this brief. These are the original merits hearing record, and the Board’s sanction hearing record. These records will be referenced herein as “H.R.” and “S.R.” respectively. Likewise, exhibits from the Board’s merits hearing record will be referenced using the same nomenclature they had in the original hearing. Exhibits offered at the Board’s sanctions hearing will be referenced as “Sanctions Exhibits.” 2 UEO notes that Appellant School District indicated in its Response to UEO’s Motion for Sanctions that “it first became apparent during the hearing that Mr. Sansoucy’s appraisal report contained material errors and that some of the testimony elicited by Utica from Mr. Sansoucy on cross examination undermined statements and conclusions in Mr. Sansoucy’s appraisal report.” Thus, the issue ofmateriality has been conceded by the party that offered Mr. Sansoucy’s testimony. That concession highlights the procedural awkwardness ofelevating Mr. Sansoucy to the status ofa party. The authority to concede the materiality ofthe testimony ofa witness lies with the party that offered the testimony to the Board, not the professional witness who testified. 3

- 7. At the Board’s sanctions hearing, Appellee presented the testimony of Grant Hammer. Mr. Hammer is an expert on natural gas processing and has responsibility over UEO’s operation ofits Kensington, Harrison and Leesville, Ohio natural gas processing facilities. Mr. Hammer provided testimony regarding the actual operation ofthe Kensington facility, what the Kensington documents and drawings prove (or disprove), and the products made by, stored at. and shipped from the Kensington facility. Mr. Hammer also addressed the reasonableness or rationality ofvarious statements made by Mr. Sansoucy. Mr. Hammer’s testimony was consistent with and supported by Kensington engineering drawings and facility documents. As discussed in detail below, in addition to providing evidence addressing the false testimony raised in its original motion, UEO provided evidence at the sanctions hearing that Mr. Sansoucy testified falsely about equipment, and tanks and products that he asserted existed at Kensington that, in fact, do not exist. Some ofthat non-existent equipment would be more than 150 feet tall and; would occupy an aggregate space as large one square mile. UEO showed that Mr. Sansoucy testified repeatedly and in detail about the existence ofnon-existent products made by giant non-existent equipment. For example, he testified about non-existent “deethanizers” which he claimed were located “at the front ofthe train.” He claimed those non-existent pieces of equipment produced non-existent ethane which was stored somewhere onsite in non-existent tanks for that purpose. Mr. Sansoucy testified that pure propane was produced at Kensington and that there is a “pure propane” product line from Kensington to Harrison (37 miles) when, in fact, there is no such product made at Kensington. Kensington has no equipment to produce propane. UEO’s Motion set forth many specific allegations oftestimonial misconduct. Although that caused the Motion to be lengthy, the sheer volume ofthe false testimony was material and 4

- 8. also bore strongly on the question ofintent. Thus, the length ofthe Motion was necessary. Yet, despite Mr. Sansoucy’s plea to be treated as a party and permitted to participate at hearing on the Motion, he failed to appear at hearing to try to explain any ofthe false testimony set forth in the Motion. Indeed, opposing counsel offered no evidence ofits own that might cast Mr. Sansoucy’s false testimony in a more favorable light. The Board’s Power To Sanction a Witness. II. The Board’s has power to bar an unreliable witness from testifying as a sanction. A. R.C. 5703.02(D) provides that the Board may adopt and “enforce all rules relating to the procedure ofthe board in hearing appeals it has the authority or duty to hear.” Ohio Adm. Code. 5717-15(0) provides that the Board swears its witnesses. It has the statutory authority to administer that oath. R.C. 5703.03. The oath certainly “relat[es] to the procedure ofthe board in hearing appeals.” It follows that the Board has authority, based in statute, to enforce that oath. Indeed, Ohio Adm. Code 5717-1-15(A)(15) expressly provides for a sanction of “denial or suspension of appearing and qualifying as an expert witness in designated matters before the Board.” Thus, the Board’s rule already specifies the Board’s sanction remedy to enforce the oath it administers. Opposing counsel’s argument that the Board lacks authority to sanction an expert witness is necessarily an argument that the Board’s own rule lacks statutory authority to underpin it. That is a very heavy legal lift. R.C 5703.02(D) very plainly authorizes the Board’s rule. Exclusion of an expert witness in future proceedings is well settled as a remedy to address false testimony by an expert witness. A tribunal’s remedies for addressing unscrupulous expert witnesses has been succinctly addressed as: The absolute protection ofthe privilege [witness immunity from being sued by the parties for testimony provided] does not empower a witness to violate his oath 5

- 9. Tribunals can disqualify unscrupulous witnesses with impunity, however, from appearing in future proceedings. Day V. Johns Hopkins Health Sys. Corp., 907 F.3d 766, 773 (4^'^ Cir. 2018). The Board’s own rule barring witnesses from future proceedings as a sanction for misconduct is consistent with such authority. It is error to phrase the question ofthe “power to sanction” in general terms rather than specifically addressing the specific sanction requested by UEO. For example, a tribunal’s power to extract a monetary sanction is a very different inquiry from the question ofits power to exclude a witness. The first question is addressed to the power ofthe tribunal to deprive the sanctioned entity ofproperty. However, the second question is addressed to the core statutory functions ofthe tribunal, i.e., enforcing core hearing procedure (i.e., the witness oath) and determining the reliability of a witness. Likewise, sanctions aimed at depriving a person of property are subject to due process limitations that do not exist for procedural sanctions such as barring a witness from testifying. In truth, the power the Board would exercise to issue the “sanction” requested in this case (suspension ofthe privilege of appearing as an expert witness) would be the same power it routinely exercises when it issues an evidentiary ruling regarding the reliability and admissibility of expert testimony. It is illogical for the Board to have the power to exclude testimony of a witness for lack ofreliability on evidentiary grounds such as bias, but lack the authority to bar an unreliable witness as a sanction for false testimony. In either case, the reliability ofthe witness is compromised. Mr. Sansoucy’s argument undermines the Board’s authority to determine the credibility and admissibility ofwitnesses before it. It cannot function at all without that power. The Board’s authority to determine the reliability oftestimony to be offered and determine whether or not to allow such testimony is “power” the Board exereises routinely. Mr. 6

- 10. Sansoucy’s argument that the Board is powerless to stop him from testifying before it, even ifhe flagrantly provides false testimony, is notable for its coneeit. It highlights Mr. Sansoucy’s view that the Board is merely a vehicle to support his vocation as a professional witness (i.e., the Board assists him, not vice versa). Mr. Sansoucy has no constitutionally protected “right to testify” Mr. Sansoucy’s counsel has argued that he has a constitutionally protected due process right to testify before the Board such that the Board must afford him notice and a hearing before that “right to testify” is infringed. The Board laudably tried to act quickly on the eve ofhearing to answer the question ofMr. Sansoucy’s participation in the sanctions matter. Thus, the question had little briefing from the parties to assist the Board. Unfortunately, the Board erred when it overrode its own rules and prior decision and transformed Mr. Sansoucy from a mere B. paid witness into a party. Appellee did not quibble over that decision because the Board’s error was and is harmless to Appellee (other than the additional expense of addressing Mr. Sansoucy’s brief). The record overwhelmingly establishes that Mr. Sansoucy intentionally provided false testimony for days at a time on many subjects, and no amount of “lawyering” for Mr. Sansoucy will change that record. Indeed, Mr. Sansoucy’s failure to show up and testify at the Board’s sanction hearing to explain himselfmakes that point more eloquently than any argument in his defense. Nonetheless, for the sake ofprocedural clarity, (i.e., identifying the true parties in this sanctions proceeding). Appellee wishes to assert that Mr. Sansoucy has no constitutionally protectable interest of any kind in the Board’s decision to bar him from testifying. The Board controls who testifies before it. The Board will never be required to afford a witness the right to contest his own exclusion (nor will any quasi-judicial orjudicial tribimal in the State of Ohio be forced to elevate witnesses to the role ofparty with the right to argue their own credibility or 7

- 11. admissibility). Unless monetary sanetions (i.e., a property interest) are proposed against a witness, the witness does not have any eonstitutionally proteetahle interest in the Board’s findings on issues of eredibility and reliability. Due proeess rights to notice and a hearing come into play where there is deprivation of a life, liberty or property interest. A future expectation to testify before the Board as a paid expert witness is not a life, liberty or property interest. Testifying before the Board for a fee is not a vocation that is protected by the constitution. The Board is not Mr. Sansoucy’s employer. The Board’s decision to bar a witness from testifying before it does not prevent that witness from pursuing his or her true vocation. The Board is not stopping Mr. Sansoucy from being a licensed engineer or an appraiser or whatever vocation he chooses. The Board does not have to bend its procedure to protect Mr. Sansoucy’s perceived “righf’ to testify as a paid witness. Otherwise, every court in the state would have to provide expert witnesses their own separate hearing before they could he excluded on reliahility grounds. It is absurd to elevate the alleged “constitutional right” ofthe professional witness to testify above the actual case in which the witness was called to testify such that additional hearings with counsel for the witness are required to protect that “right.” Mr. Sansoucy’s reputation is not protected by the Constitution. The 3’''* Circuit Court of Appeals described the governing law on that subject as follows: Clark’s contention and the jury’s finding that he had a liberty interest in his reputation which served as the predicate for his due process claim must surmount the formidable barrier imposed by Paul v. Davis, 424 U.S. 693, 47 L. Ed. 2d 405, 96 S. Ct. 1155 (1976). In that case, the United States Supreme Court held that reputation alone is not an interest protected by the Due Process Clause. held that financial harm resulting from the loss of clients “is insufficient to transform a reputation interest into a liberty interest. we 8

- 12. The possible loss of future employment opportunities is patently insufficient to satisfy the requirement imposed by Paul that a liberty interest requires more than mere injury to reputation. Clark V. Falls, 890 F.2d 611, 619-620, (3'''* Circuit Ct. ofApp. 1989). UEO has searched but found no authority granting expert witnesses constitutional rights to protect their reputation from adverse decisions addressing their credibility such that they must be granted notice and a hearing before a decision on that topic can be issued. To be clear, the Board could relegate Mr. Sansoucy’s brief on this sanctions matter to the trash can and refuse to hear him at all, and the Constitution would not be offended in any fashion. He simply has no interest at stake that is protected by the Constitution and he will have no appealable right from any decision the Board makes on the Sanctions Motion. UEO does not raise this issue to exclude Mr. Sansoucy’s counsel from participating.^ Rather, UEO raises the issue to advise the Board ofMr. Sansoucy’s position in relation to the Board’s decision on sanctions. Mr. Sansoucy argues that he has the rights of a party in the sanction matter now before the Board (and yet he is only a paid witness and the only sanction requested is to bar him from testifying), while he simultaneously argues that the Board’s own power to weigh reliability and admissibility of evidence is diminished to the point that it cannot stop him from appearing before it even ifhe offers intentionally false and misleading testimony. Mr. Sansoucy grossly overstates his own “rights” in this matter. At the same time, he grossly understates the Board’s own statutory power to control and administer its own hearing procedures and address reliability ofwitnesses. In fact, the opposite is true. The zenith ofthe Board’s powers are realized when it is evaluating evidence and witnesses before it. The Supreme Court of Ohio itself defers to the ^ UEO is ofthe opinion that the Board would be wise as a policy matter to clarify that Mr. Sansoucy, like all witnesses, has no due process protected “right” to testify before the Board and to the extent that its prior decision appeared to say that, upon further consideration it disavows that position. 9

- 13. Board’s credibility findings unless those findings have no support in the record at all. It would be strikingly odd ifthe Board were forced to receive testimony from a witness that it knows has lied to it in the past because the right ofthe witness to falsely testify exceeds the Board’s duty and power to stop it. A sanction barring a lying witness from testifying in future proceedings is basically a ruling that the witness has demonstrated sueh a personal reliability deficit that his testimony will he deemed inadmissible as an evidentiary matter going forward for the time specified by the sanction. The Board easily could make such admissibility rulings addressed to the reliability of a one would question its authority to do proposed witness pursuant to motions to exclude and no Similarly, ifthe Board determines that Mr. Sansouey lied to it, of course it has the authority so. to bar him from testifying in future proceedings as a sanction. Such an action would simply avoid piecemeal rulings on motions to exclude on evidentiary grounds in the future (i.e., that the witness is demonstrably unreliable because he has lied under oath in the past). In either event, the Board is exercising the same power to exelude an expert witness for the same reason (questions ofreliability). As a policy matter, ifthe reliability problem exists, Ohio counties and school districts should know that as soon as possible (i.e., before the witness is hired rather than after he takes the stand as in the instant case). The Board’s own rule provides express authority act to protect Ohio taxpayers and taxing authorities from known unscrupulous witnesses rather than keeping that institutional knowledge to itself and allowing the problem to persist. The Board should sanction an expert witness when it is clear that witness deliberately testified falsely. All deliberate false testimony is criminal misconduct. Ifit is material it is perjury and a felony. Ifit is not material it is “falsification” and a misdemeanor. That said, sanction requests against witnesses are rare. Counsel for UEO has 75 years oflegal practice between the three of to C. 10

- 14. them. In that time, they have filed exactly two sanctions request against a witness. In both cases, that person was Mr. Sansoucy. In both cases Mr. Sansoucy offered false testimony best described as being “made up,” and offered it for days at a time on multiple subjects. It was embarrassingly clear in both cases that he had little to no idea what he was talking about. In both cases, rural Ohio counties were misled and received little or nothing in return for large fee expenditures. In both cases, Ohio taxpayers paid enormous sums in expert witness and legal fees to correct an evidentiary record that Mr. Sansoucy deliberately distorted. In both Mr. Sansoucy argued that the Board should overlook his false testimony because the taxpayer’s counsel was a “vicious” bad guy for pointing out his testimonial misconduct. He argued in both cases that it was his tremendous effectiveness rather than his false testimony that the real reason for the sanctions motion. In both cases, his testimony and report was the opposite of effective, it achieved nothing for his client. His false testimony simply made the Board’s proceeding extremely expensive for the parties involved (and made Mr. Sansoucy richer at their expense). It now has happened twice at the Board with the same witness. The Board should not allow a third iteration. Witnesses usually are extended the benefit ofthe doubt with regard to the question of cases. was whether a limited amount oftestimonial errors were intentional. This practice is good public errors is somewhat self-correcting. These types of policy because the result ofumeasonable strongly damage the credibility ofthe witness. For that reason, counsel calling that witness error tries hard to avoid them. The nature ofMr. Sansoucy’s “errors” are fundamentally different than the normal case before the Board. It is apparent horn the Appellant School District’s pleadings that Mr. Sansoucy was not truthful with his own client’s legal counsel. It was apparent at the Board’s 11

- 15. hearing that counsel for Appellant was surprised and dismayed when cross examination shed light on Mr. Sansoucy’s outlandishly false testimony. Likewise, the sheer volume ofthat outlandishly false testimony on technical matters could not have been anticipated by the School Board’s counsel. Unfortunately, attorneys are ill equipped to catch flagrantly false testimony on technical matters from their own expert witness. Cormsel for the school district did not have the benefit of company engineering experts pointing out Mr. Sansoucy’s bizarrely false claims. He had only Mr. Sansoucy. In that regard, UEO will once again make clear that it does not lay any blame for Mr. Sansoucy’s misbehavior upon either counsel for the school district or the school district itself Should the Board issue a decision sanctioning Mr. Sansoucy, it would be appropriate to make clear therein that neither the school district nor its counsel bears any blame for Mr. Sansoucy’s misconduct. Indeed, they were victims. The Board should recognize that testifying before it can be very lucrative. Mr. Sansoucy invoiced an Ohio school district over $400,000 for his “work” in this case. Because witnesses have absolute immunity from lawsuit for the testimony they provide, the unscrupulous expert witness can thumb his nose at the parties injured. UEO has no means to seek recourse in an Ohio court for the false testimony Mr. Sansoucy offered against it. Americanjurisprudence lays the ponsibility of addressing false testimony on the tribunal where the testimony was offered. The Board should balance the public policy value of extending the benefit ofthe doubt to witnesses, with the public policy value of ensuring professional witnesses do not use the Board’s forum to perpetrate frauds on Ohio taxpayers and public officials. The public policy need for truthful testimony outweighs affording the witness the benefit ofthe doubt in appropriate cases. That case is before the Board res 12

- 16. 1. The Board should sanction any witness when it is clear the witness perjured himself under Ohio law. A principal question the Board must resolve is how to diseem when the false testimony has gone beyond the benefit ofthe doubt. UEO is eonfident that like Justiee Potter Stewart explaining how he defined “obseenity,” i.e., “I know it when I see it,” the Board can use its to weigh competing polieies and deeide when to sanetion a witness that testified falsely. However, it should be manifest to the Board that in cases where a witness eommitted felony perjury, such testimony should not be overlooked. Similarly, the Board should eonsider the volume ofwitness misconduet. Was it a one-off statement that might be overlooked, or was it pervasive? Indeed, ifthere is a high volume of false testimony, that speaks to the question of intent. The more something happens, the less likely it is that it was aecidental. Ohio law addressed to perjury is a useful guide for the Board in this ease. At a bare minimum, ifperjury oceurred, that is a serious abuse ofthe tribunal and the parties, and the Board should address it. Beeause false testimony is the issue before the Board, it is also instructive to review Ohio judieial authority regarding the questions of intent and materiality of the false testimony. Those questions are pertinent to the sanetions request ofUEO. R.C. 2921.11 provides in pertinent part: 2921.11 Perjury. (A) No person, in any offieial proeeeding, shall knowingly make a false statement under oath or affirmation, or knowingly swear or affirm the truth of a false statement previously made, when either statement is material. (B) A falsification is material, regardless ofits admissibility in evidenee, if it ean affeet the eourse or outeome ofthe proeeeding. It is no defense to a charge under this seetion that the offender mistakenly believed a falsifieation to be immaterial. common sense Mr. Sansouey admitted that his testimony on a number oftopics was false. Likewise, all ofthe aetual parties to the tax dispute before the Board are in agreement that material “errors” exist in 13

- 17. his testimony and report. However, as argued in his pretrial statement, Mr. Sansoucy claims he did not knowingly make the false statements. He asserts his errors were made in good faith. Mr. Sansoucy argues that he only made false statements with regard to personal property to which he did not assign a value. Presumably, this latter argument is intended to support the premise that his false testimony was not material. Appellee will address each ofthese claims. “Knowingly making a false statement” for purposes of the Ohio perjury statute includes making statements where the witness is consciously ignorant of the truth of the statement. State V. Bayless, 14 Ohio App. 2d 11, *14, (4* Dist. 1968), is the seminal case in Ohio addressing the question ofthe mental state required to support a perjury conviction. In that case, the court rejected the defense argument that because the witness was not absolutely certain ofthe falseness ofthe testimony to be offered he was “innocent” of suborning perjury. The court rejected this argument and explained its decision as follows: In 70 Corpus Juris Secundum 473, Perjury, Section 17b(l), the author says: Under the rule that in order to constitute perjury a false statement must be knowingly false, it must appear that the accused knew his statement to be false or was consciously ignorant of its truth. (Emphasis added). 2. * * Likewise, the court cited with approval language from a survey of court cases on the subject. The court, in the first paragraph ofthe syllabus in People v, Agnew, 77 Cal. App. 2d 748, 176 P. 2d 724, said: * * *A reckless statement [in a judicial proceeding] which is not known to be true is ‘perjury’ if in truth such averment is false. (Emphasis added). In Butler v. McKey, 138 F. 2d 373, 3 77, the court said: The argument is not tenable that a perjury charge cannot be sustained against an affiant who sets forth hearsay matter as a fact. In a situation where no specific information has been imparted to him, if a man swears that he has received such information, and ifhe swears that because of such information, a defendant could not with due diligence be found or a defendant was concealing himselfto avoid service, he subjects himselfto 14

- 18. liability for perjury, for he has corruptly made a positive statement. * (Emphasis added). Thus, a reckless statement (i.e., an affirmative statement made where the declarant was in fact consciously ignorant ofthe truth ofthat statement) will support a conviction for perjury in Ohio. This means that a witness does not get to make positive averments offact as ifhe knows what he is talking about, when the truth is that the witness is making up the testimony (i.e., it may or may not be true but the witness is consciously ignorant ofthe truth). Those are corrupt positive statements. The truthful answer in such a situation is obvious, “I don’t know.” It is clear in Mr. Sansoucy’s case that he repeatedly made up outlandishly false statements offact to support his conclusions. He knew he was making up his testimony and at best he had no idea whether the testimony was true or false. At worst, he knew it was false. Either fact pattern is perjury under Ohio law. In that regard, the Board need not determine which ofthese corrupt fact patterns was the one that happened at the Board. Making up facts to convince someone to act to her detriment on that erroneous understanding ofthe facts is a universally bad act. The same “conscious ignorance” mental state that supports a criminal charge ofperjury also would support a civil fraud case ifthe false statement was made to induce entrance into a contract. Note the following treatise explication of the difference between a “mistake” for contract law purposes and “fraud.” Restatement ofRestitution, §6 (1937) c. There may be ignorance of a fact without mistake as to it, since mistake imports advertence to facts and one is ignorant ofmany facts as to which he does not advert. However, mistake is always based upon ignorance which leads to a belief in the existence ofnon-existing things or the non-existence of existing things. This is true even though there is no advertence to the particular facts which, if known, would prevent the mistake. Thus where a person makes a second payment of a debt which previously had been paid by his agent, his payment is mistaken, whether or not he adverts to the possibility of a prior payment, since he is mistaken in believing in the continued existence ofthe debt. On the other hand. H: * 15

- 19. one who knows that he is ignorant is not mistaken since he has no belief as to the existence or non-existence of facts. (Emphasis added). Section 8 ofthe same Restatement carries that notion forward to explicate the difference between a “mistake” and actionable “fraud” for contract law purposes as follows: c. Fraud. A misrepresentation is fraudulent ifit is made to another with loiowledge that it is untrue and with the intention that the other shall act thereon. Likewise, it is fraudulent for a person with a like intention to make an untrue statement if he realizes that he does not know whether or not it is true. (Emphasis added). Whether it be civil or criminal law, Americanjurisprudence uniformly looks askance at actors pretending they know something they do not in order to convince others to act on that bad information to their detriment. Thus, ifthe Board determines Mr. Sansoucy was “consciously ignorant” ofthe truth ofhis testimony (i.e., he was making it up), sanctioning that bad act is warranted. Aside firom the fact that conscious ignorance does not excuse false testimony, there is another more fundamental problem with Mr. Sansoucy’s “empty head and pure heart” defense. To support his conclusions, Mr. Sansoucy claimed to have performed an enormous amount of study ofthe equipment and drawings ofthe Kensington facility. It was this work and study that justified his six figure fees. IfMr. Sansoucy actually had performed the amount ofwork he claimed, he would have known the testimony he was providing was false (i.e., he emphasized for days in his testimony the hundreds ofhours he spent studying to make his head full, not empty). Thus, ifhe was actually ignorant regarding the truth ofhis false statements about non-existent equipment, non-existent products, etc., that means he testified falsely regarding the extent and nature ofthe study he said he performed. He cannot have it both ways. 16

- 20. When is false testimony material? False testimony is material when it could affect the outcome ofthe proceeding. R.C. 2921.11(b). Thus, testimony from Mr. Sansoucy addressed to taxable real property that he believed would require Appellee to pay a higher tax bill is material. False testimony offered by a witness to buttress his own credibility is material under Ohio law. For example, a witness has been successfully prosecuted for perjury where he told a tribunal he passed a polygraph exam when he knew he did not. State v. Irvin, 2015-Ohio-798, 2015 Ohio App. LEXIS 802 (Ohio Ct. App., Wood County 2015). Obviously, credibility of an expert witness can affect the outcome of the proceeding. 3. In fact, the credibility and reliability of an expert witness is particularly material. It forms the basis for the ability to offer opinion testimony and have that testimony treated as factual evidence rather than rank speculation. For that reason, before the Board can address the credibility ofthe testimony it must first address both the reliability ofthe expert himself, and the reliability ofhis report as a matter of admissibility under Evid. R. 702. Ifthe expert lies about his experience or the work he said he did, that testimony obviously is material to the case because it forms the basis upon which his opinion testimony is admitted into evidence. Mr. Sansoucy offered reams oftestimony regarding: (1) non-existent piping systems, (2) non-existent equipment (some ofit fifteen stories tall), (3) the function ofthat non-existent equipment, (4) non-existent products and how those non-existent products are stored in tanks he declared to be taxable real property; (5) claimed expertise in designing and preparing bids for piping systems, and having prepared a “reproduction cost new” valuation ofpiping systems, when he admittedly cannot read American National Standard piping specifications necessary to identify the type ofpiping he is costing; (6) enormous amounts ofwork performed to study 17

- 21. drawings and texts to give him very granular understanding of everything at Kensington. All this testimony intentionally painted a picture of a very experienced and knowledgeable witness with specific expertise concerning the function and operation ofKensington. That narrative, iffalse, is inarguably material because it bears upon Mr. Sansoucy’s credibility and the reliability ofhis entire report and testimony. In fact, the record establishes that Mr. Sansoucy made up that testimony to persuade the Board that he and his report were credible and correct. His false testimony often directly supported conclusions he had offered (e.g., the 56 piping systems false testimony supported his 15/56 fraction for classifying helical piles and piping racks) that were themselves pure guesswork. This false testimony was material; it was not offered by accident. The sheer volume and nature ofit is conclusive. The Method Followed in Thi.s Briefwith Regard To Addressing Mr. Sansoucy’s False Testimony. UEO will follow a simple model in the remainder ofthis brief It will address Mr. Sansoucy’s claims regarding the amount and nature ofwork he purported to perform in informing himselfabout the Kensington property. UEO then will set forth one or more related false statements made by Mr. Sansoucy. Finally, UEO will identify the evidence in the record that exposes Mr. Sansoucy’s statements and claims as intentionally false. The question in each instance will be “whether there is any rational basis for the false statement(s)?” A related question in each instance will be, “what work did Mr. Sansoucy claim he did that would have provided him knowledge to avoid the false testimony ifthe work actually done?” For example, if a piece of equipment, a piping system, or a product ofthe facility does not exist, and Mr. Sansoucy testified that it does, and every document attached to his own report refutes his claim, it should be clear then that he did not read or understand those III. was 18

- 22. report documents. Ifhe claimed he studied those documents for hundreds ofhours, he lied. Likewise, where there is no rational basis for the false statement (e.g., non-existent equipment or a non-existent product), that statement is also perjurious because at best he was consciously ignorant ofthe truth ofthe statement but made corrupt positive statements offact while hiding his true lack ofknowledge. The Board’s record establishes that Mr. Sansoucy’s false testimony was not a few one-off statements. It happened over and over again. The sheer volume ofit removes any benefit ofthe doubt about Mr. Sansoucy. He made the strategic decision in this sanctions matter to rest on the record and not open himselfto additional questioning. Mr. Sansoucy did not appear at the sanction hearing because it is not possible to explain his testimony. There are no reasonable excuses he could offer on such a multiplicity ofmaterial misstatements. He could not possibly have believed everything he said when there was no rational basis for it. Further testimony could not have helped him in the sanctions matter, but certainly could have hurt him. Ifhe testified at the sanctions hearing and told the truth he would be forced to concede. Ifhe did not tell the truth, he would further expose himselfto civil and/or criminal sanction. Thus, the strategic decision not to testify was really his only option. The Work Mr. Sansoucy Claimed To Have Performed. To evaluate whether Mr. Sansoucy’s false testimony was due to a reasonable mistake it is IV. necessary to review and evaluate his claims about the work he performed to support that testimony. In other words, if a witness claims to have performed exhaustive study of a subject to credibility, then the witness cannot also claim support his conclusions and buttress his own ignorance on that subject as a shield against allegations offalse testimony. The two positions are mutually exclusive. 19

- 23. From the beginning Mr. Sansoucy portrayed himself as possessing an enormous amount of experience and familiarity with “everything that’s at Kensington.” He stated in direct voir dire examination: Q. You testified earlier that Kensington is kind of a conglomeration of different pieces and parts. Is there any piece ofproperty, whether real or personal, at Kensington that you haven’t seen before? A. I’ve seen everything that’s at Kensington. Whether we valued everything at Kensington identical, no, we haven’t, because they’re all brand new, it’s state of the art. But I’ve seen every type of facility that’s at Kensington elsewhere in its individual nature or in its conglomeration. There’s nothing unusual about this collection of assets; it’s just how they put them together to do what they need to do. (Emphasis added). H.R. Vol. I: 156. Thus, during voir dire Mr. Sansoucy portrayed himselfas a person with preexisting vast knowledge who then studied drawings, process flow diagrams and vendor documents to become an expert on the Kensington plant. He professed great familiarity and experience with every asset at Kensington both individually and in its conglomeration before he ever got to the drawings. He had seen “every type of facility that’s at Kensington.” He also clearly testified that he knew exactly what assets existed at Kensington or how else could he claim to have seen “everything” and that there was “nothing unusual about this collection of assets”? very A. Despite purporting to be a report of expert testimony on engineering facts, the Sansoucy report does not set forth any facts relevant to the real versus personal property question. Mr. Sansoucy’s report purported to address two subjects, property classification (i.e., real personal), and valuation. The vast bulk ofthe tax dollars in dispute involved the legal issue ofproperty classification. UEO did not obtain or present valuation evidence for the $56 million worth ofproperty Mr. Sansoucy claimed was improperly classified because his misclassification was flatly wrong as a matter of law and fact. The major dispute between the versus 20

- 24. parties was the real versus personal property classifieation question. Aeeordingly, the faets and law pertinent to that question form the great majority ofthe Board’s evidentiary reeord. There are a few crueial facts relevant to the legal question ofproperty classification as real or personal property that one would expect to be set forth in detail in an expert report addressed to that question. They are: (1) how the property is physically attached to the real estate; and (2) whether the property primarily benefits the real estate generally or the particular business being conducted on the real estate? Mr. Sansoucy purported to address both ofthose inquiries for all ofthe property on the site. See Sansoucy Report at 55 and 60. However, Mr. Sansoucy’s report does not explicate those pertinent facts for any ofthe property he claimed to classify. Instead, Mr. Sansoucy’s report consists ofrepeated uncorroborated claims about the sheer volume ofwork he did or what he sources he reviewed to answer these questions followed by his bare legal conclusions on property classification. The relevant facts on the classification question to which he purportedly applied Ohio law are absent from the report. The Board will not find a section in the report where Mr. Sansoucy sets forth how the items ofproperty are attached to the real estate. The Board will not find a section in the report where Mr. Sansoucy sets forth the facts on how particular items ofproperty benefit either the real estate generally or the specific business conducted. He purports to have done this investigatory work for hundreds and hundreds ofitems. Yet, he does not set forth in his report those facts for even one item. His report relies upon his uncorroborated claims of a “detailed” investigation he performed as a substitute for showing the results ofthe purported investigation. Mr. Sansoucy did not produce any contemporaneous notes addressing that real versus personal analysis despite the fact that page 14 ofhis report asserts that he prepared “detailed 21

- 25. notes.” He did not bring any notes to hearing as a referenee when asked questions about function attachment of various items ofproperty. Instead, he repeatedly tried (and failed) to find references to various items of equipment at hearing in the indexes of generic textbooks. Thus, the Sansoucy report was grossly anomalous from the start. Ifthe investigatory and analytical work had been performed with regard to the key facts ofproperty attachment, function and benefit, it is reasonable to expect that analytical work and supporting facts to be plainly visible in the report or at least in his working notes. Yet, there is nothing. Mr. Sansoucy’s report is devoid of facts and has only legal conclusions on the real versus personal property question. This technique precluded any meaningful ability to determine ifhe correctly discerned the facts he claimed to rely upon prior to hearing. His failure to include the relevant facts on the classification question in the report shifted emphasis to Mr. Sansoucy’s testimony. Counsel for Mr. Sansoucy has complained that Mr. Sansoucy was kept on the stand for an inordinate amount oftime. However, the length oftime Mr. Sansoucy was cross- examined was a direct result ofhis failure to include the facts in his report, a report which purported to have reclassified $56 million of equipment at Kensington. It was Mr. Sansoucy’s effort to preclude meaningful review ofhis conclusions prior to hearing by failing to include relevant facts in his report that was the direct cause ofhis multiple days on the stand. Mr. Sansoucy’s strategy was to show up at hearing and backfill facts via his own testimony to support his classification conclusions. His report very often pointed generally to the entire body ofplant drawings as “support” for his conclusions without specifying any. In some cases, a specific drawing was referenced that said the opposite ofMr. Sansoucy’s claims. He had no specific notes to refer to during the hearing, and he did not produce any during discovery. It became clear as the Board’s hearing proceeded that Mr. Sansoucy was simply making up facts or own 22

- 26. support his conclusions, and that had been his intention all along. He presumed that the lack ofnotice ofhis made up factual claims would preclude effective cross-examination. However, the things he was saying under oath directly contradicted all available documentary evidence including the facility drawings he claimed to have studied for hundreds of hours. To an expert actually familiar with the Kensington facility, it was abundantly clear that Mr. Sansoucy had no idea what existed there, much less how the property functioned or how it attached to the real estate. For example, Mr. Sansoucy blithely stated that all transformers at affixed to the realty” without providing any evidence to corroborate that statement. H.R. Vol. 2: 416. Grant Hammer indicated that to his knowledge, none ofthe transformers are attached to the concrete pads they rest on, and that he had specific knowledge that the four very large step down transformers (which was about $15 million ofthe total) were definitely not attached because he had been involved in replacing one ofthose transformers. S.R. Vol. 2: 237-238. This fact by itselfwould be dispositive ofthe real versus personal question for transformers that were not bolted to the concrete pads they rested upon. See American National Can Co. v. Tracy, 72 Ohio St. 3d 150,153 (1995) (addressing the question of whether a very large transformer sitting on a concrete pads like those at Kensington were real or personal property and concluding: The record shows that this transformer, a large piece of equipment, was neither bolted nor otherwise affixed to the concrete slab upon which it rested. Am-Nat admits that it could be moved with a crane. It was, therefore, free-standing and not a structure or part ofreal property.). Once again Mr. Sansoucy simply made up the facts (transformers affixed to concrete pads) that he believed supported his classification conclusion. As shown below, Mr. Sansoucy repeatedly made up testimony to support either his own credibility or his conclusions (or both) with rational basis to support it. to was 59 the site were “structures no 23

- 27. Work Mr. Sansoucy claimed to have performed to support his conclusions. Mr. Sansoucy claimed in his report to have done an enormous amount of work to support his real versus personal property determinations. Mr. Sansoucy indicated in his report that the “problem to be solved” was the “separation” of real property and personal property, the “identification and quantification” of the taxable real property, and the valuation ofthat property. See Appellant’s Ex. 1, (Sansoucy Appraisal Report) at 8. Likewise, Mr. Sansoucy described the scope of his services as including “analysis necessary to develop credible assignment results, and research required to understand the physical interrelated characteristics of the property and improvements.” Id. At pages 8 to 10 of his report, Mr. Sansoucy set forth many tasks he reportedly performed to support his conclusion. Among those tasks he set forth were: • Detailed review and education of modern natural gas cryogenic processing facilities through various textbooks, articles and publications; • Review of Ohio law regarding the taxability and classification of property similar to the Kensington tangible assets and tangible property; • Create the process for determining whether an item is real or personal property under Ohio tax law as it applies to the Kensington faeility; • Review law and case law decisions in Ohio regarding the taxability of eertain types of property as real, personal, or business related nontaxable tangible property or a business fixture; • Develop a final methodology for determining the real property criteria for inventory ofthe Kensington facility; • Preparation of a detailed construction take-off ofthat portion of the Kensington Facility determined to be taxable real property based on the actual Kensington engineering drawings, including a review of nearly all of the engineering drawings in Kensington for their designation and property type; • Tabulation and sorting ofthe real property portion of the Kensington Facility into specific taxable areas ofreal property; (Emphasis added). B. 1. 24

- 28. Appellant’s Ex. 1 at 9. Mr. Sansoucy emphasized that he considered “detailed construction and engineering plans and specifications” to support his work. Id. at 13. Mr. Sansoucy claimed that he reviewed “nearly all ofthe engineering drawings in Kensington.” Id. at 9. On page 4 ofhis report, Mr. Sansoucy described his competency for the Kensington also assignment as follows: For purposes ofthis appraisal, I have striven to increase my competency related to the valuation of Kensington. I believe that I have adequately become competent for the valuation of this facility, for which, at this point, there is no other of this operating magnitude in Ohio, provided, in this appraisal, a detailed list and summary of documents and information considered. I considered 4 or 5 separate text book sources and did a complete overview of each of these texts. I performed a detailed site tour, took a number of photographs with my associate, asked a number of questions, prepared detailed notes, and compared this facility with the remaining other facilities of its type, although not as extensive, in the State of Ohio. I have reviewed 1,500 -2,000 detail drawings as neeessary for the real property portion of the plant, including the overview drawings of the plant. (Emphasis added.) Mr. Sansoucy claimed that he received 15,000 plant drawings, which he “reordered” into a 1497 workbook, then from that set of 1497 drawings he “isolated those drawings which related to the criteria outlined earlier in this report.” Id. As part of my additional self-learning, I have page directly to the real property improvements based at 66. Those selected 520 drawings formed Appendix L of his report. In addition to the 15,000 on drawings, Mr. Sansoucy indicated that he reviewed 85 boxes of cost records which included additional “business equipment and machinery drawings” that Mr. Sansoucy referred to as “work files.” Id. Indeed, Mr. Sansoucy asserted that: In addition to the drawings, we asked for, and received, the ability to review all of the purchase orders, vendor bills, cost ledgers, slips and vendor submissions, which in and of themselves, include the balance of the engineering drawings, when supplied by an individual vendor. 25

- 29. Id. at 69. Thus, Mr. Sansoucy claimed in his report that he comprehensively reviewed “all” Kensington drawings and cost records, and that the cost records themselves included additional drawings which he also reviewed. Mr. Sansoucy testified to enormous amounts of review and study of Kensington documents and that analysis was the basis of his real versus personal property determinations. At hearing, Mr. Sansoucy’s repeated his claims ofwork performed. But, his testimonial claims differ markedly depending upon which day the claim was made. From days one through five, Mr. Sansouey professed to have reviewed everything Kensington. He attested to having prehensive knowledge. When Mr. Sansouey discovered over the weekend between days five and six ofthe hearing that over half ofthe 56 piping systems he claimed to have studied did not aetually exist, he changed his earlier testimony. For the first time he admitted that he had not reviewed drawings for those systems he had classified as personal property. Instead, his new position was that he made his real versus personal determination for those piping systems knowing nothing more than their names. These later declarations cannot be reconciled with the prior claims and claims made in the report regarding comprehensive understanding ofhow all ofthe property at Kensington “physically interrelates,” and his study of engineering documents and process flow diagrams to confirm his classification of all 56 systems (both real and personal). Likewise, the later claims cannot support a claim of good faith (e.g., how does one go about making a good faith determination that property is real or personal if one’s “review” ofthe facts is so lacking that one does not even know whether the property exists?). Thus, Mr. Sansoucy’s attempted excuse 2. eom leaves a great deal to be desired with regard to excusing his conduct. At his deposition, Mr. Sansouey testified that Kensington was a collection of assets and ‘understand what was there and what did they do.” Appellees Ex. 2: his “first objective” was to 26

- 30. 71; See also S.R. Vol. 1: 95. Notably, he did not take this opportunity to indicate that he had not reviewed the drawings for more than half ofthe 56 piping systems that he repeatedly testified existed. Neither did he explain that he made no effort to ascertain what did or did not exist at Kensington (which was where his testimony ultimately was going to go). In addition to the work claims within his report, Sansoucy testified repeatedly through the first five days ofhearing about the analysis and work that he did to separate Kensington assets into real property and personal property, which he then assigned a cost to the real property he identified. He testified that he alone made the decisions “on what property was real or personal.” H.R. Vol. 1:16.'^ Sansoucy testified that he and his staffperformed extraordinary amounts of study ofplant drawings and cost records: On the engineering drawings I told you what I did. drawings on a drive and the table of contents. We went into the 15,000 drawings on the drive, and through the table of contents, we extracted those areas that might be categories ofreal property. We eliminated areas that might or probably likely were categories ofpersonal property. *** We got 15,000 [S]o we got the 15000, we got the table of contents, and we reduced that to 1490 or 1500 drawings. We looked at every single drawing and collected from the 1500 and came up with about 500 plus that we were going to use for the quantity takeoff and everything else. The entire process of selecting the drawings, going through all of those drawings, took at least 100 hours. Probably took 2-1/2 man-weeks in my estimate. So that would be at least 100 hours on that before we start taking off stuff. Just selecting, finding, reading, and coming up with potentially real property. See H.R. Vol. I, at 127-128; See also Vol. II, at 300-301 (Sansoucy stating that he identified 1,497 drawings to be used in his report from total of 15,000 drawings). Mr. Sansoucy elaborated UEO noted the suggestion at the Board’s sanction hearing that Mr. Sansoucy was somehow mislead by his employees. Aside from the fact that Mr. Sansoucy made clear that he alone did the property classification work, he did not take the stand to claim as a factual matter that somehow he was misled by his employees. He never said even one time on the record that he was misled by his employees. When he was caught in his false testimony, his repeated defense was to claim the false testimony was “not germane,” or simply that he had never said anything to the contrary, not that his employees deceived him. Thus, as a factual matter in the record, he was not misled. 27

- 31. make clear that this 100+ hours of studying both drawings and the “table of contents” for the drawings was exclusive of additional time spent in determining cost (i.e., the “2 14 man-weeks” ofwork was all addressed to study offimction and benefit ofthe systems). Id. at 130-131. Mr. Sansoucy also testified that his firm went through “85 banker s boxes of cost records and vendor drawings in Houston that was in addition to that 100+ hours of staring at the drawings and the index for same. Id. at 132-135. That was an additional 260 hours of document analysis and review for a total of at least 360 hours. Id. at 128-129. Mr. Sansoucy testified that he had advised Mr. Stedronsky for “all of the property on the site” on the issue of classification: advised Mr. Stedronsky on the technical and physical characteristics of all of the property on the site that is primarily related to the realty and property on the site that is primarily processing property. And the property gray in the middle. As an engineer in layman’s terms.” H.R. Vol. 3: 481. He did not testify at this point on day three that he had not reviewed property he considered to be personal at all without reviewing drawings and without even determining ifit existed (which was his desperation position on day 6 of the hearing). He very clearly testified that he advised as to “technical and physical characteristics” of all of it, real, personal and “gray in the middle.” to Mr. Sansoucy testified under direct examination that in order to be credible in his report he had to have done the “research required to understand the physical interrelated characteristics of the property and the improvements” and that “ifyou don’t research it, it’s not going to be credible; starting with what constitutes real and what’s personal.” H.R. Vol. I, at 192. At no point did Mr. Sansoucy testify in those first five days ofhearing that he had classified dozens of systems and items of equipment as personal property that he believed existed at Kensington (1) without even looking for drawings of those systems or equipment and 28

- 32. (2) without even determining whether that equipment aetually existed at Kensington. When he would falsely testify as to the existenee or funetion of that non-existent equipment, he never disclosed any uncertainty. He always testified in terms of concrete fact. Similarly, he would explain how he determined the non-existent piping systems (of which there were 29) physically interrelated” with the 27 piping systems that did exist. Of course, ifhe actually had never determined how the systems interrelated one with another, he would not have testified there were more than twice as many systems as there actually were. The non-existent systems related to and interfaced with nothing at Kensington. Any real study would have disclosed that glaring fact. Sansoucy claimed to have applied the legal flowchart process outlined in his report “to Id. at 96. He described his flow determine the distinction between real and personal property, chart at page 58 of his report as the methodology “to look at each system back and forth***”. Likewise, Mr. Sansoucy testified that he made his real versus personal property determinations as follows: Q. Before you go on, I just want to clarify, how did you determine or how did you make that initial determination ofthose things that were clearly personal and then those things that might not be clearly personal? A. I went through the drawings and we did the site tour, we saw them. Went through the drawings. We researched as much of the public record as we could. So for example, this particular Figure 12 comes out ofthe company’s records, and they are public records, and it outlines, for example, the primary components ofthe site to help me identify what all ofthese various components were. And in identifying those I then immediately made a decision - I say “immediately” -1 made a decision if they were, without a doubt to me, personal property, and moved them aside. Then I went to the drawings to look at the flow charts in those drawings, the process flow diagrams, to see if, number one, any of those might have intersected their operation with the real property, per se, or did I in fact make reasonable decisions on moving them out of the real property category and intro the personal property in the first instance by virtue ofwhat they are. So I went back through, looked at the process flow diagrams, and especially on, you know, beginning the process of identifying what’s out and what’s in the gray. 29

- 33. H.R. Vol. 4: 714-715. Thus, contrary to his day six testimony when he claimed that he made personal property determinations without reviewing anything at all, he very clearly testified previously that he studied drawings for all of the property at Kensington. He specifically and repeatedly indicated that he studied the process flow diagrams to form his conclusions on classifications for the 56 piping systems. His foregoing elaim that he studied the property Kensington documents for those systems he determined were personal to see if his initial conclusion was correct cannot possibly have occurred for even one of the 29 non-existent piping systems. Otherwise, he certainly would have noticed 29 missing systems out of 56 possible (yet he failed to find any). Mr. Sansoucy went onto describe examples ofhow he applied that analysis of function to discrete items of property at Kensington as small as individual C02 detectors and various other equipment at the site. Id. at 271 (compressor buildings); Id. at 273-275 (C02 detectors); Id. at 276-278 (flare piping system); Id. at 279-282 (Sansouey’s phrase, “cryogenic towers”). Sansoucy indicated that his analysis was to determine whether the component at issue benefited See Id. at 280 (explaining his view that the “cryogenic towers^ personal property because “ifs there to benefit the process”); 281 (“by all rights ifs a fixture but it’s there to benefit the process.”). Mr. Sansoucy testified throughout the first five days ofhearing that his review and study ofthe Kensington drawings were the basis ofhis conclusions; “[t]he first and most important step in determining real property is to determine how the property is designed, built and affixed the ground, and that’s what the engineering documents show you.” Id. at 31. He said, “we looked carefully at the drawings on the use and the affixation to the land, et cetera. are the site or the “process.’ to Id. at 197-198. 30

- 34. Sansoucy summarized the description ofhis real versus personal property analysis: So this starts the process of how we developed the individual units and quantities and developed the difference between the real and the personal, and we went into that particular category, such as piping, how did we develop - which piping is taxable, which is not taxable, and then how did develop the quantities ofthe taxable portion ofthat particular category, for example. Id. at 298. Sansoucy made clear that the plant drawings allowed him to “see the property” and the intent ofthe owner” for the equipment at Kensington. The best method to do—if you can. If you’ve got a new property or an aged property that has engineering drawings, the best way to establish the first partial inventory, fractional inventory of property is if you have engineering drawings, so you can actually see the all of the property.***But if you do have a new property and you do have drawings, you can now go through and start isolating those portions of the seven criteria to develop what part of that is real, because you can actually see—you can see the property. You can see the intent of the owner. ***So having the drawings is very beneficial, but getting the drawings on a site ofthis size and weeding through them to identify the set of categories is tedious. It’s not ultimately hard. It’s tedious. =^**We provided a chip, a flash drive of all of the drawings for the site, 15,000 pages of engineering drawings, and the index. (Emphasis added.) we see were Id. at 299-300. Mr. Sansoucy testified that he also reviewed “shop drawings” prepared by vendors in the “85 banker’s boxes” ofmaterials that was in addition to the 15,000 drawings. Id. at 300-301. He indicated that from the 15,000 drawings he whittled it down to 1,497 drawings to be used in his report: So that’s the 1,497 drawings. What we did is went through and colored those 1,497 drawings from what we believed was real property based on the seven categories. We colored the portion that we felt was real. And then the 520 drawings that constitute Appendix L is a copy of those colored drawings that are in the 1,497. Id. at 302. Mr. Sansoucy described his real versus personal determination process as involving much “study” ofthe drawings. 31

- 35. Q. What was the general process? A. Exactly what you just said. We went on a site tour. We valued the property. We looked at the drawings. We studied and we debated, studied the drawings again, and then made a decision as to which we felt business - business fixtures versus real property. H.R. Vol. V, at 1052. It is worth noting that in addition to this comprehensive study ofthe drawings regarding property classification (i.e., use, function, benefit and affixation to the ground), Sansoucy claimed that he also determined whether the property at Kensington suffered from any functional depreciation. He said that he performed research to ascertain whether there was any functional H.R. Vol. 2: 329.^ Of course, the depreciation at Kensington, “we researched, we found none.' facts uncovered by this purported research were missing from the report. To perform functional depreciation analysis one must be fully aware ofthe particular assets that are employed to perform a particular function to compare those assets to current state ofthe art technology. Not surprisingly, Mr. Sansoucy failed to appear at the Board’s sanction hearing to explain how he performed his alleged functional depreciation “research” without actually knowing what equipment existed at the site and apparently suffering under beliefs that multiple non-existent products were made by non-existent equipment. For example, how did Mr. Sansoucy research and determine that the non-existent deethanizer or non-existent nitrogen rejection unit he described in his testimony did not suffer from any functional depreciation? As is explained more fully below, a nitrogen rejection unit is completely unnecessary to process Kensington gas. Mr. Sansoucy’s claimed research into fiinctional depreciation would have disclosed that no one would pay for that giant useless asset he believed existed ... had he actually performed such research. ^ Functional depreciation: Decline in the productive or service ability of a capital asset due to obsolescence. See http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/functional-depreciation.html 32

- 36. Mr. Sansoucy’s day six testimony that he determined property was personal without actually finding and reviewing the property in the Kensington documents, and without determining ifthe property existed, cannot he reconciled with his previous claims to having achieved an understanding ofhow all ofthe systems and equipment at Kensington interrelate with each other, his “first objective” of determining “what was there,” and the enormous amount oftestimony in which he claimed that all ofhis real versus property classification decisions were made from his study and review ofthe drawings. At no point during the first five days ofthe merits hearing or in his report did Mr. Sansoucy state that he made real versus personal classification decisions without reviewing Kensington documents. To the contrary, he testified that he looked at process flow diagrams and engineering drawings to confirm his classification of property as real or personal. H.R. Vol. IV: 714-715; Vol. V, at 1052; quoted with emphasis, supra. When shaping his own narrative about work and study allegedly performed, Mr. Sansoucy certainly did not disclose that he failed to even determine the existence ofmore than half ofthe piping systems listed in a general legend. Appellant’s Ex. 1, Appendix L at Bates 383. Such an admission, although true, would have fatally undermined his reliability. The claims Mr. Sansoucy made in his report and during that first five days ofhearing concerning work performed are starkly inconsistent with (1) his claims on day six and (2) those in his Prehearing Statement filed prior to the sanctions hearing after he realized his previous false testimony was known and untenable. The claims made from days one through five regarding work done cannot be reconciled with the new day six and seven claims. The nature ofMr. Sansoucy’s statements are such that they cannot spring from honest error. Mr. Sansoucy knew he hadn’t studied the Kensington documents to confirm his classification conclusions, yet he peatedly testified under oath that he had. In those first five days oftrial, these statements were re 33

- 37. concocted purposefully to bolster credibility and support conclusions. Those statements were false. Mr. Sansoucy offered them to mislead the Board later proven impossible. They about the work he performed. The inescapable conclusion is that they were lies offered in some were cases to bolster his eredibility as an expert and in others to directly support his conclusions. Sansoucy’s false testimony specifie to piping systems. It was within the context of his elaimed of study of the property at Kensington that Mr. Sansoucy purposefully offered his opinion thaf certain types of property at the facility were partially real property. For pipe racks and helical piles (steel foundations screwed into bedrock), Sansoucy determined a eost and then applied a fraetion in order to cost the rmdivided portion of eaeh piece of steel in what he classified as a real property strueture. See Appellants Ex. 1, Appendix F. The fraction he applied was 15/56. The notes to the report indicate that the 15/56 fraetion was derived by taking the 15 piping systems Sansoucy had determined were real ratio of all 56 piping systems he elaimed existed on the site. H.R., Vol. II, at 380- 3. property as a 383 (“You’ll see pipelines on the legend, pipe rack. This is what’s carrying pipelines, 56 total pipeline systems”). See, also. Appellant’s Ex. 1, Appendix F, at Bates 7, and 10 at note 2 (referencing Appendix J, Bates 146 “structural working notes”). Mr. Sansoucy testified under direct examination that he determined there were 56 piping systems at Kensington: Q. Okay. How did you determine, one, that there were 56 total at Kensington and, two, you would use 15 ofthose? A. In the piping portion of the appendix on the tables, F-3, that’s going to be second to last. That’s going to be Table F-6. The piping portion ofthe drawings starts on Bates 381, and you ean see on table F-6 that the piping goes all the way through to Bates 379 to 517. Within the drawings in piping, on Bates 383, there is a piping legend, and that piping legend provides a list of all of the various piping systems. Q. Did you color those? 34

- 38. A. And then we colored those that we felt were site utilities that related to the use of the real estate and not the property. They were basic site utilities being used, and that gives us the 15. Now, on an absolute basis -- yeah, it’s 15. When you go to the notes, you’ll find other piping systems that we were also adding up in the notes. But as we worked through those, we dropped them off as being more likely related to the personal property than the real property. So what you see in the notes is gone from the table, but this is what’s in the table, is shown on the legend. Q. Okay. We’ve got the legend on the board, and those are your colors you added? A. Yes, they are. Q. And ifwe look through the drawings of all the pipes, will we see those colors? A. Ifyou go through the pipe drawings, you’ll see those colors. H.R. Vol. II: 383-384; see also Id. at 426 (“we selected from the 56 systems that we believe are real property systems that serve the utility ofthe property***.”). Mr. Sansoucy testified that he applied his real versus personal property analysis to every single one ofthe 56 piping systems he had identified. Q. Then when you made these cuts did you actually go through and apply your methodology on page 59 to each of these systems to just double check yourself? A. You can apply it ifyou wish. Q. No, I was asking if you did that? A. I do - did. Q. Did you? A. Yeah. Q. In applying that flow chart, did you also consider or at least review from the documents the function of each of the 56 piping systems? A. Yes. 35