This document discusses the history of efforts by workers and labor unions to reduce the standard work week and enact an 8-hour work day. It describes how in the late 19th/early 20th century, labor unions organized around reducing work hours as a key issue to address long hours and exploitation by employers. Over time, unions succeeded in negotiating shorter maximum work weeks and overtime provisions. However, real wages stagnated and unemployment remained high. The document argues that reducing overall work hours could help address these ongoing problems by spreading work more evenly and giving workers more leisure time and power relative to employers.

![Olszanski 4 Shorter Work Week

As early as 1822, Philadelphia millwrights and mechanics demanded a ten hour day,

and in 1835 carpenters, masons, and stonecutters in Boston staged a seven-month strike in

favor of a ten-hour day. The strikers demanded that employers reduce excessively long hours

worked in the summer and spread them throughout the year. Again the movement for a ten-

hour workday returned to Philadelphia, where carpenters, bricklayers, plasterers, masons,

leather dressers, and blacksmiths went on strike. The Massachusetts legislature debated the

issue of the 10 hour day, having been petitioned by workers and their unions, including those

of the textile mills in Lowell. A number of states actually enacted 10 hour day legislation, but

it had little effect as corporations found ways around it, including forcing employees to sign

contracts calling for 12 or 13 hour work days.11

Building Trades workers in London conducted a massive strike for a 9 hour work

day in 1860-1861.12 In the U.S., real wages dropped precipitously between 1860 and 1865,

just as the bosses introduced speed-up on a massive scale to increase production. An average

working day of eleven hours was often stretched to twelve or fourteen hours. Strikes for

higher wages and a shorter work day erupted across the country in 1863, in the midst of the

Civil War.13 In 1865 the San Francisco Trades’ Union publicly appealed for an 8 hour day.

Eight Hour Leagues were organized all over the Bay area, and put pressure on local

politicians. In 1867 the San Francisco Board of supervisors passed an 8 hour ordinance.

In February 22, 1868 “thousands celebrate[d]passage of a state law” declaring the 8 hour day

the standard. In 1868-1870 San Francisco bosses reacted, and broke the 8 hour day with

scabs.14 On August 20, 1886 the National Labor Union called on Congress to enact

legislation limiting the standard work day to 8 hours, and its agitation is credited with

reducing the average working day in the U.S. from 11 hours in 1865 to 10.5 in 1870.15

The depression of 1883-1885 saw increased unemployment and poverty, while those who](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorterworkweektermpaperrevised2018-180424141201/75/A-Shorter-Work-Week-revised-2018-6-2048.jpg)

![Olszanski 8 Shorter Work Week

Squeezed time and again by falling real wages due to inflation outstripping hard-won

union wage gains, U.S. workers got into the habit of making up for lower wages and

wages lost to frequent lay-offs by working as much overtime as they could get when

the economy was booming. Over and over again they fell back to longer hours for less

pay and the ever-present threat of unemployment.

Marx had predicted in the 19th century that capital would consistently try to

extract more and more surplus value from fewer and fewer workers:

"It is the absolute interest of every capitalist to press a given quantity of labor

out of a smaller, rather than a greater number of labourers..." 28

The capitalists have kept true to form. Marx also argued that high levels of

unemployment benefit capital and hurt labor. Constituting an industrial reserve army, the

unemployed are willing to work for lower wages, thus tending to lower wage rates

throughout the labor market.29 In 1943, Polish economist Michal Kalecki proposed a national

policy of full employment as an antidote to the domination of labor by capital through the

reserve army of the unemployed. He warned that capitalists would oppose full employment

policy as a threat to their hegemony, and suggested that “new social and political institutions

would be needed…which will reflect the increased power of the working class.”30 His classic

argument is cited by Schor, and was important in formulating Labor Government Policy in

Britain and Australia after World War II:

[Under] a regime of permanent full employment, ‘the sack’ would cease to

play its role as a disciplinary measure. The social position of the boss would be

undermined and the self assurance and class consciousness of the working class

would grow….[The bosses’] class instinct tells them that lasting full employment is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorterworkweektermpaperrevised2018-180424141201/75/A-Shorter-Work-Week-revised-2018-10-2048.jpg)

![Olszanski 9 Shorter Work Week

unsound from their point of view and that unemployment is an integral part of the

normal capitalist system.31

While capitalist economists consistently insisted that real wages could only rise with

increased productivity32, a powerful labor movement in the 1930’s, 40’s and 50’s proved that

in fact they could rise as a percentage of total revenues, by taking the difference out of profits

and executive compensation.33 The trouble was, high unemployment tended to put a damper

on wage increases in lean times, while inflation ate away at real wages in better times. And

the labor movement started a sharp decline in power after it purged its militants in the

McCarthy era. Schor, in her 1992 book The Overworked American, emphasizes Organized

Labor’s abandonment of the shorter workweek in 1956 as a direct result of the CIO purge of

alleged communists and the expulsion of 11 left-led CIO unions. Indeed, the CIO under

Steelworkers President Phillip Murray signed on to the cold war as staunch anti-communists,

with Murray announcing that “the single issue before the [1949 CIO] convention was the

expulsions.”34 “Labor’s move to the right had a profound impact on the hours question.”

Schor insists. 35 “Unions [during the cold war started] adopting the longstanding rhetoric of

management” such as the International Association of Machinists 1957 red-baiting statement,

“Will the Soviets cut THEIR Overtime?”36

In the 1940’s, British Labor Party economist William Beveridge argued for a

national full employment policy for Great Britain, and by implication, for the industrial

world. In support of the trade union movement, he insisted that “…only if there is work for

all is it fair to expect workpeople, individually and collectively in trade unions, to co-operate

in making the most of all productive resources, including labor.” 37 A Keynesian, Beveridge

emphasized the role of government in providing the “outlay” to make up for shortfalls in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorterworkweektermpaperrevised2018-180424141201/75/A-Shorter-Work-Week-revised-2018-11-2048.jpg)

![Olszanski 10 Shorter Work Week

investment by private capital. With productivity rising due to technological change,

Beveridge recognized that, even accepting the classical economics of Adam Smith, and the

productivity bargain as espoused by the AFL, an ever larger pie could produce a larger slice

for labor, which could mean higher wages, shorter hours of work, or some of each. Beyond

Smith, he saw as not only possible but desirable, that the share of the pie going to labor could

be increased, owing at least in part to increased labor demand in a full employment

economy.38 Lord Beveridge defined the productivity equation thusly: “Increased

productivity per head mathematically involves either increased consumption per head [higher

wages] or idleness, which must be taken either in the form of leisure [shorter work hours] or

unemployment” 39 In simpler language, as workers get more efficient, and produce more in

fewer hours, we either get higher wages for our labor, or we get the same wages for fewer

hours, or some of us get unemployed and the capitalist gets to keep higher and higher profits.

Who gets what is determined by how well organized and powerful workers are, and whether

we can and do fight for higher wages, shorter hours, or both. Workers get what we are

powerful enough to take, and we keep what we are powerful enough to hold.

Business unionists in the American Federation of Labor (AFL), stressing labor-

management cooperation to raise productivity, articulated what has become known as the

U.S. wages/productivity bargain in their 1925 wage policy statement, which “oppose[d] all

wage reductions,” and “…urged upon management the elimination of wastes in production..”

It warned that,

Social inequality, industrial instability and injustice must increase unless the

workers’ real wages, the purchasing power of their wages, coupled with a

continuing reduction in the number of hours making up the workingday, are

progressed in proportion to man’s increasing power of production. 40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorterworkweektermpaperrevised2018-180424141201/75/A-Shorter-Work-Week-revised-2018-12-2048.jpg)

![Olszanski 11 Shorter Work Week

Going against mainstream management thought, and “propelled by a vision of

Liberation Capitalism,” the paternalistic Kellogg Cereal Company of Battle Creek, Michigan

instituted a six hour day in 1930, as a tactic to cope with depression-era unemployment.

Company management found the move increased productivity 3 or 4%. Management found

“The efficiency and morale of our employees is so increased, the accident and insurance rates

are so improved, and the unit cost of production is so lowered that we can afford to pay as

much for six hours as we formerly paid for eight.” In fact, “they cut the workday to six

hours, while eliminating breaks and terminating bonuses for unpopular shift times. Workers

were given a 12.5 percent hourly raise, so standard daily pay only fell by about fifteen

percent.” The experiment was short lived, however, and the concept of increasing

productivity by shortening work hours never caught on as a strategy for business. 41

President William Green of the AFL argued in a depression-era 1935 pamphlet

entitled “The Thirty-Hour Week,” that a shorter work week with “no loss of take home pay”

would place purchasing power in the hands of workers and the formerly unemployed who

would now share jobs, thereby releasing “pent up consumer demand” and “stimulating

industrial production in business activity,” likewise “provid[ing] the material means for

higher standards of living for the American people and would make effective new and

widespread demands for goods and services.” Green reiterated the AFL call for “a reduction

in the number of hours worked per day and the number of days worked per week,” to offset

technological job loss at the 1935 AFL Convention. 42

Denouncing Green and the AFL’s “lackey-like” collaboration with business, radical

William Z. Foster considered the proffered productivity bargain as “no more than a platonic

argument of higher wages in return for more production.” 43 Left-led unions in the CIO](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorterworkweektermpaperrevised2018-180424141201/75/A-Shorter-Work-Week-revised-2018-13-2048.jpg)

![Olszanski 19 Shorter Work Week

according to Dr. Suzanne Schweikert. The doctor also lists hypertension, diabetes, heart

disease, obesity, infertility and mental health disorders as consequences of too many hours of

work—and not enough rest and leisure. “Not enough time,” to eat properly, recreate,

meditate, exercise, and recuperate cause workers to get run-down, inviting all sorts of health

problems, says Schweikert. Pregnant women are particularly at risk. Many work too many

hours “in order to gain the benefits of health insurance, although the pressure resulting from

overwork is making us sick,” a “vicious cycle,” according to Schweikert.57

Stephen Bezrucha of the University of Washington School of Public Health concurs, and

cites statistics placing the U.S. “25th, behind almost all other rich countries, and quite a few

poor ones,” [author’s italics] in terms of health indicators such as infant mortality and life

expectancy. He argues there is a direct connection between this unhealthiness and the

overwork of its middle and lower classes, competing as we are to gain ground in our

hierarchically structured society.58

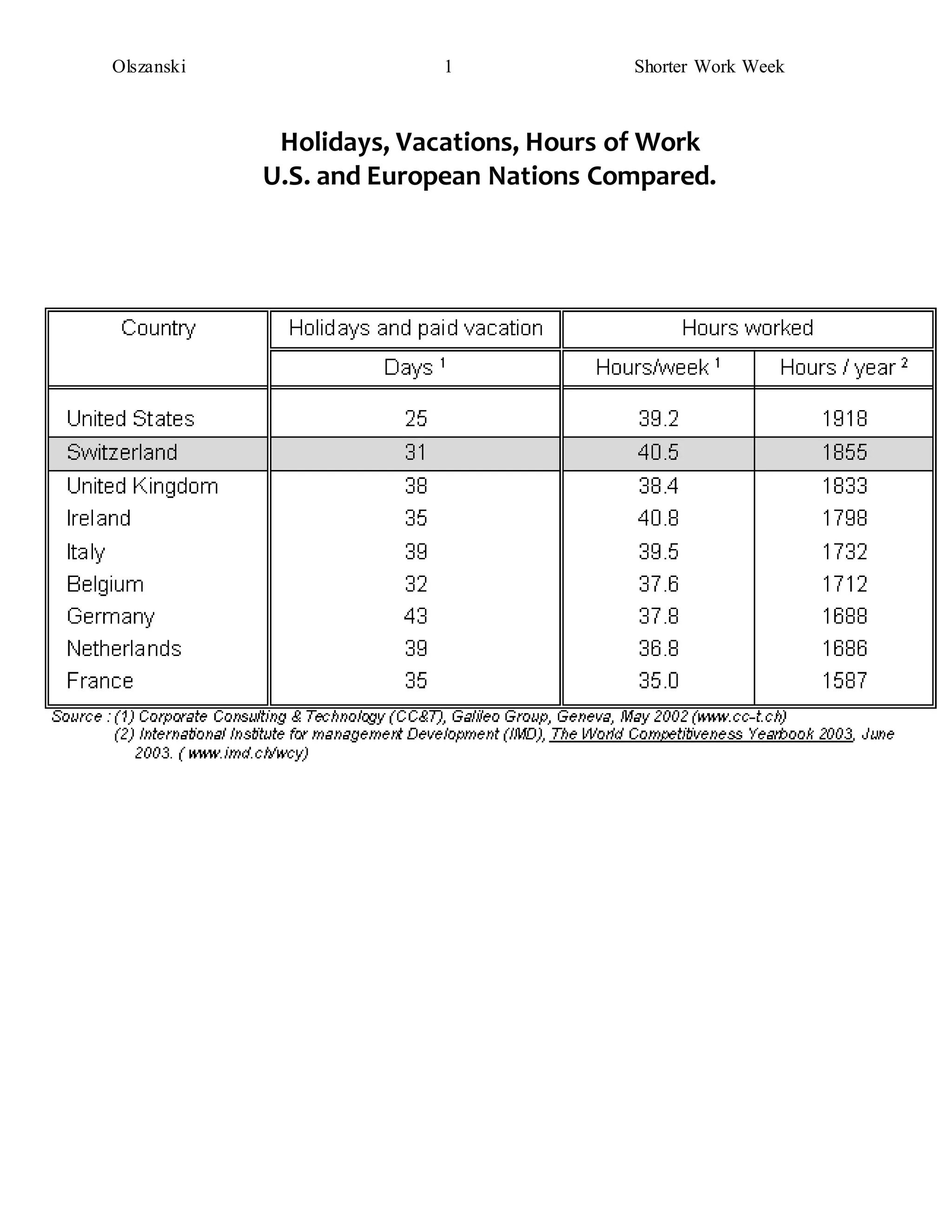

European workers have largely rejected the obsessive consumerism, individualism

and “get it while you can” attitudes of their exceptionalist “American” brothers and sisters.

Class consciousness, with a preference for collective over individual solutions, has led these

union members and their leaders to seek more leisure time and share the work and divide the

productivity bonanza much more equitably than is done here in the states. Unions, like

governments in Europe are still led to a great degree, by Communists, Socialists and Social

Democrats. Once again it’s simple math, and union workers in Europe have figured it out:

shorter hours spreads available work hours around, and if you’re organized, you can force the

bosses to share the benefits of increased productivity, instead of hogging it all.

Europe’s 20th century labor movement, led by Germany’s huge metalworkers union,

IG Metall, won a 371/2 hour work week after a nation-wide strike in the 1980’s, then a 35-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorterworkweektermpaperrevised2018-180424141201/75/A-Shorter-Work-Week-revised-2018-21-2048.jpg)

![Olszanski 21 Shorter Work Week

Here in the U.S. hours of work have been going in the OTHER direction during the

same period. According to pro-business Dutch economist Jaap van Duijn, top executive at

the Dutch Robeco financial consultancy group, “The average working week in the United

States has gone up in the past ten years, whereas for us, it's gone down." Van Duign was

arguing for a stronger “work ethic” among Dutch workers, in order to increase productivity.

“They [Americans] are content with just two weeks of holidays [vacation].” The business

guru moans. 64

Dutch radio reports that European businesses and governments are screaming at workers

to adopt the work styles of their American cousins:

Longer working hours for the same pay: that's what a number of companies in

Germany, France and the Netherlands are proposing for their employees. The

employers say it's a question of pure necessity in order to stay competitive. The

trade unions are calling it blackmail.65

But the Dutch, along with most Europeans, aren’t having it.

The statistics are borne out in experience, with the Dutch rejecting the idea that

their life must correspond wholly to their work. Except in highly internationalised

areas such as law firms, people work the hours their contracts say they should work.

Even ambitious Dutchmen can leave the office on time, knowing that to do so will

not prejudice their chances of advancement. As hard as it is for those in the Anglo-

American tradition to grasp, it simply doesn't look bad to walk out the door at

5.30pm.66](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorterworkweektermpaperrevised2018-180424141201/75/A-Shorter-Work-Week-revised-2018-23-2048.jpg)

![Olszanski 1 Shorter Work Week

End Notes

1 See, Mike Olszanski, “Time to Fight For Jobs” in The Voice of the Rank & File, East

Chicago, Indiana: Rank & File Caucus at Local 1010 USWA, December, 1989), 1-2.

2 Juliet B. Schor, The Overworked American, the Unexpected Decline of Leisure, (New York:

BasicBooks, 1991), 107-138.

3 See Jerry Flint,“Unions Meet Resistance in Trying to Cut Workweek”, New York Times,

April 16, 1978 https://www.nytimes.com/1978/04/16/archives/unions-meet-resistance-in-

trying-to-cut-workweek-other-priorities.html also

https://reuther.wayne.edu/files/LR000880.pdf

4 Lawrence Mishel, Jared Bernstein, Heather Boushey, The State of Working America,

2002/2003, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003), 153-167.

5 Schor, 53-54.

6 Karl Marx, Capital, (New York: International Publishers, 1967 [1867]), 188.

7 For a detailed explanation of surplus value and formulas by which it is computed see

Marx, 149, 201, 204, 207 and 209, and in Capital, Book II, 218. Marx defines surplus

value as "..an exact expression for the degree of exploitation of labour-power by

capital, or of the labourer by the capitalist." (p. 209)

8 Schor, 43-47.

9 See Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, 170-171. See also Marx 168-171 “The value of labor

power resolves itself into a definite quantity of the means of subsistence.”

10 Marx, 265-269.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorterworkweektermpaperrevised2018-180424141201/75/A-Shorter-Work-Week-revised-2018-41-2048.jpg)